Abstract

A procedure involving microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) followed by solid-phase extraction (SPE) was established for the extraction and purification of three bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids from Stephania cepharantha, and a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method was developed for the quantification of the target alkaloids. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Phenomenex Luna Phenyl-Hexyl column. Prior to the HPLC analysis, the alkaloids were rapidly extracted by an optimized MAE process using 0.01 mol/L hydrochloric acid as the solvent. The MAE extract was subsequently purified by SPE using a cation-exchange polymeric cartridge. The MAE–SPE procedure extracted the three alkaloids with satisfactory recoveries ranging from 100.44 to 102.12%. In comparison with the MAE, Soxhlet and ultrasonic-assisted extractions, the proposed MAE–SPE method showed satisfactory cleanup efficiency. Thus, the validated MAE–SPE–HPLC method is specific, accurate and applicable to the determination of alkaloids in S. cepharantha.

Introduction

Stephania cepharantha Hayata (Menispermaceae) has been widely used in Chinese folk medicine for the treatment of various diseases, including rheumatism, diarrhea, leukopenia and parotitis (1, 2). The tuberous root of this plant contains a large number of alkaloids, of which the bisbenzylisoquinolines of cycleanine, isotetrandrine and cepharanthine are major components, and these possess a diverse range of pharmacological activities, e.g., anticancer, anti-HIV, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and immunoregulatory effects (3–13). Thus, these alkaloids are commonly used as chemical markers for the quality control of S. cepharantha.

Most analytical methods for the quantification of alkaloids in S. cepharantha are based on chromatography. Because of the complexity of natural matrices, sample preparation involving both extraction and purification procedures is crucial. A number of extraction approaches such as maceration, heat reflux extraction and ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE) have been applied to the extracts of S. cepharantha prior to the chromatographic determination of alkaloids (14–16). The former two approaches require long extraction times (14, 15). The UAE method requires a 40-min ultrasonication and overnight presoaking, and thus is also time consuming (16). Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) is a promising approach for the extraction of plant constituents because of its simplicity, short extraction time and low solvent consumption (17, 18). Although this technique was introduced for alkaloid extraction from S. cepharantha (19), the reported MAE method was used only for the extraction and thus was not validated for quantification. Moreover, the extraction solvent is complex and contains a large amount of organic solvent, i.e., the upper phase of hexane–ethyl acetate–methanol–water (1 : 1 :1 : 1, v/v/v/v) containing 10% triethylamine (19). Therefore, there is a need to develop a simpler and more environmentally friendly MAE method for the determination of alkaloids in S. cepharantha.

In order to reduce the matrix compounds and increase the lifetime of the chromatographic system, it is necessary to purify the plant crude extracts (20–22). A liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) method is usually employed for the cleanup of crude extracts from S. cepharantha (14, 15). However, the LLE method is time consuming, labor intensive and uses large amounts of organic solvent. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is faster, consumes less organic solvent and produces cleaner extracts compared with classical LLE. Therefore, we established an SPE method using basic alumina sorbent to prepare samples for analyzing cepharanthine in S. cepharantha (23). However, the SPE method was associated with reproducibility problems during simultaneous extraction of different alkaloids. Moreover, better cleanup efficiency is still in pursuit.

In recent years, MAE coupled with SPE has drawn significant attention for sample pretreatment because it offers not only high extraction efficiency but also satisfactory cleanup efficiency. The MAE–SPE technique has been successfully applied to the analysis of various compounds in different matrices (24–26). However, no MAE–SPE methods have been developed for the quantification of alkaloids in S. cepharantha.

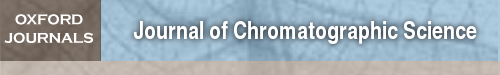

Herein, we report an MAE–SPE method for the extraction and purification of three bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids (Figure 1) from S. cepharantha. Various MAE conditions were investigated for maximizing the extraction efficiency. To achieve selective and efficient purification, six different SPE cartridges were tested, including reversed-phase and cation-exchange sorbents, and silica- and polymer-based sorbents. The proposed MAE–SPE method is compared with other sample preparation methods including MAE, UAE and Soxhlet extraction (SE). In addition, a specific high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method is developed for the quantitative analysis of the target alkaloids.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the three alkaloids in S. cepharantha. (1) Cycleanine, (2) isotetrandrine and (3) cepharanthine.

Experimental

HPLC instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

The HPLC analysis was conducted on an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC system (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a G1311A quaternary pump, a G1329A automatic sampler and a G1315D DAD (diode array detector). An Agilent ChemStation (version B.04.02.SP1) was used for sample control and data processing. HPLC separation was achieved on a Phenomenex Luna Phenyl-Hexyl column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 µm, Aschaffenburg, Germany) coupled with a Phenomenex C18 guard column (4.0 × 3.0 mm, 5 µm). The mobile phase consisted of an acetonitrile−0.5% (v/v) triethylamine aqueous solution adjusted to pH 10.0 with 10% (v/v) phosphoric acid (63 : 37). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The column temperature was kept at 40°C, and the injection volume was 20 µL. The absorbance wavelength was set at 282 nm for quantification.

Materials, chemicals and reagents

Dried tuberous root of S. cepharantha purchased from the Ningbo Dekang Biochemistry Co. (Zhejiang, China) was collected in 2011 from the Sichuan Province, and the product was authenticated by Dr Y. Kang. A Voucher specimen (S201206G) was deposited at the School of Pharmacy, Fudan University. After being dried and pulverized, the plant sample was passed through a 60 mesh sieve.

Cycleanine and cepharanthine (>98% purity) were obtained from Zhongshan Pharmcare Biotech Inc. (Zhongshan, China). Isotetrandrine (>98% purity) was isolated in our laboratory, and its purity was assessed by the HPLC–DAD method described in this article. Acetonitrile (HPLC grade) was purchased from Honeywell (Ulsan, Korea). Methanol, phosphoric acid, triethylamine, hydrochloric acid (HCl) and ammonia of analytical grade were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. (Shanghai, China). Deionized water was prepared using a Millipore Milli-Q purification system (Bedford, USA). Cleanert C18 (100 mg/1 mL), Cleanert PEP (60 mg/3 mL), Cleanert SCX (100 mg/1 mL), Cleanert C8/SCX (50 mg/1 mL) and Cleanert PCX (60 mg/3 mL) were obtained from Agela Technologies (Tianjin, China), and HR-XC (60 mg/3 mL) was obtained from Macherey-Nagel (Düren, Germany).

Preparation of standard solutions

A mixed standard stock solution of the alkaloids was prepared by dissolving cycleanine, isotetrandrine and cepharanthine in methanol, and stored at −20°C. Standard working solutions were prepared by serially diluting the mixed standard stock solution with 0.01 mol/L HCl, and stored at 4°C.

Sample preparation

Microwave-assisted extraction–solid-phase extraction

The MAE was performed on an MDS-8 Microwave Workstation (Shanghai Sineo Microwave Chemical Technology Co.). The dried S. cepharantha powder (0.5 g) was mixed with 20 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl and heated under a microwave power of 100 W at 60°C for 2 min. Then, the extract was filtered and the filtrate was transferred to a 25-mL volumetric flask followed by the addition of 0.01 mol/L HCl to 25 mL.

A 3 mL aliquot of the MAE extract solution was then purified by the following SPE procedure. The PCX cartridge (60 mg) was attached to an SPE vacuum manifold (Agilent) and conditioned with 3 mL of methanol followed by 3 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl. Next, the extract solution was slowly passed through the preconditioned cartridge. The sorbent was washed successively with 3 mL of water and 3 mL of methanol, and then eluted with 3 mL of methanol‒25% ammonia (97.5 : 2.5, v/v). The eluate was evaporated to dryness at 45°C under a gentle stream of nitrogen and reconstituted with 3 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl. After centrifugation at 10,000 r.p.m. for 5 min at 5°C, 20 µL of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC system.

Microwave-assisted extraction

The MAE procedure was conducted in a manner identical to the MAE process described for MAE–SPE.

Ultrasonic-assisted extraction

The UAE was carried out using an ultrasonic apparatus (model DL-180A, Shanghai Zhixin Instrument Co.). The sample powder (0.5 g) was ultrasonicated in 20 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl for 30 min at 45 kHz. The extract was filtered, and the filtrate was diluted to 25 mL with 0.01 mol/L HCl.

Soxhlet extraction

The sample powder (0.5 g) was extracted with 100 mL of methanol in a Soxhlet apparatus on a water bath at 65°C for 7 h. The extract was filtered, dried under reduced pressure and redissolved in 25 mL of methanol. Afterwards, the extract (1 mL) was dried at 45°C under a stream of nitrogen, redissolved in 1 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl, centrifuged at 10,000 r.p.m. for 5 min and the supernatant solution was analyzed using HPLC.

Results

Optimization of the HPLC analysis

In order to ensure good resolution of the target compounds together with a short analysis time, the category of the column and the composition of the mobile phase were optimized.

In preliminary experiments, three different HPLC columns were tested: a YMC-Triart C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 µm) from YMC, a Gemini C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 µm) from Phenomenex and a Luna Phenyl-Hexyl column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 µm) from Phenomenex. Because of the structural similarity of the three alkaloids, it was difficult to achieve good separation between cycleanine and isotetrandrine when using the former two columns. The optimized conditions for the two columns and the corresponding chromatograms are presented in the Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. The phenyl-hexyl bonded phase will often improve selectivity for aromatic compounds such as the bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids. The Luna Phenyl-Hexyl column provided much better resolution of cycleanine and isotetrandrine, and thus, it was chosen for use in further investigations.

The composition of the mobile phase was optimized by varying the organic solvent, the pH value of the aqueous phase and the percentage of the organic phase. Acetonitrile resulted in lower column pressure and better separation than methanol, and it was therefore selected as the organic phase in subsequent experiments. An alkaline mobile phase can be used to eliminate peak tailing. When the pH of the aqueous phase was adjusted to 10, the peaks of the alkaloids became symmetric, sharp and well separated. The ratio of acetonitrile to phosphate buffer (pH 10) was optimized at 63 : 37 (v/v), thus leading to the target characteristics of short analysis times and good resolution.

Optimization of the MAE–SPE procedure

Extraction of alkaloids by MAE

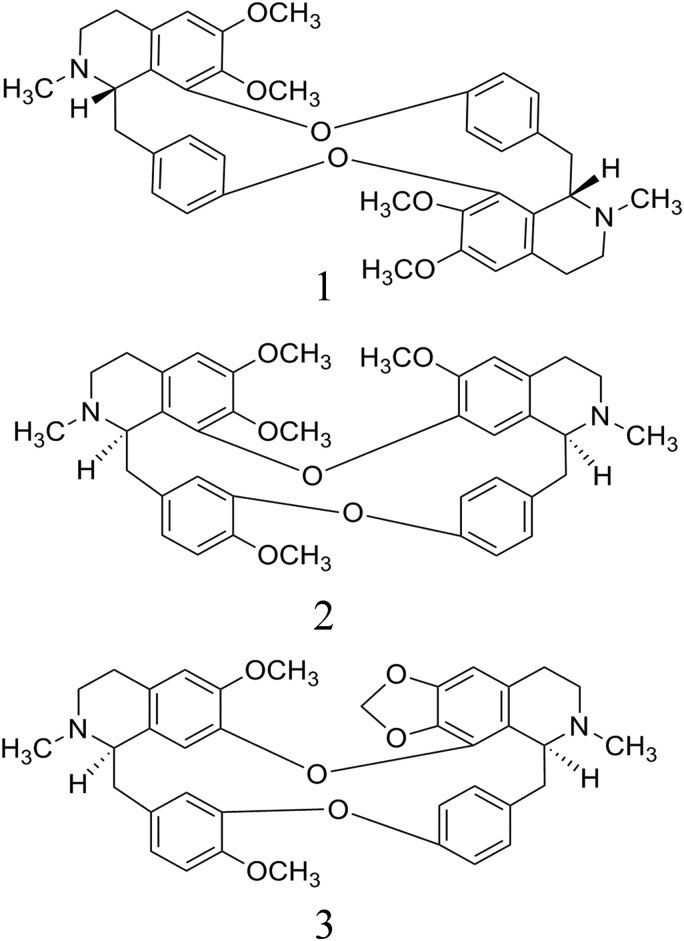

Various MAE factors including the type of solvent, liquid-to-solid ratio, temperature, extraction time and microwave power determine the extraction efficiency. The extraction yields of alkaloids under different conditions are presented in Figure 2. The significance of differences between treatments was assessed using the Student's t-test.

Figure 2.

Effects of (A) extraction solvent, (B) liquid-to-solid ratio, (C) temperature, (D) extraction time and (E) microwave power on the extraction yields of the three alkaloids from S. cepharantha (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus the level marked with “a”).

The effects of different extraction solvents, including aqueous HCl solution and aqueous methanol, are displayed in Figure 2A. The concentration of HCl in water had a great impact on the alkaloid yields. The highest yields were obtained when using 0.01 mol/L HCl. When a higher HCl concentration of 0.1 mol/L was used in our preliminary experiment, the extraction solution thickened, making it very difficult to filter. Conversely, at a very low HCl concentration of 0.001 mol/L, the yields of all three alkaloids decreased markedly and varied greatly (data not shown in Figure 2A). For the methanol–water system, the methanol concentration significantly affected the extraction efficiency. When the methanol concentration was increased from 50 to 95%, the yields of the alkaloids increased, reaching a maximum between 65 and 80% methanol; however, the yields declined at higher methanol concentrations. Among the extract solutions with high alkaloid yields, the solution extracted with 0.01 mol/L HCl could be applied directly to the subsequent SPE cleanup step, and was observed to have the lightest color, implying the lowest concentration of coextracted compounds. Therefore, 0.01 mol/L HCl was determined to be the solvent that is the most appropriate and environmentally friendly for the extraction of alkaloids from S. cepharantha.

Figure 2B shows that the extraction yields are significantly enhanced when the liquid-to-solid ratio is increased from 20 : 1 to 40 : 1 (mL/g), but a further increase in the ratio to 50 : 1 leads to a marked decrease in the yield. The initial rise may be attributed to an increase in the diffusion rate, and a liquid-to-solid ratio of 40 : 1 was deemed sufficient for the release of the alkaloids. Importantly, any excess solvent would disperse more microwave energy and result in less microwave energy absorption by the sample. Hence, a liquid-to-solid ratio of 40 : 1 was selected as the optimum condition.

The effect of temperature on the extraction efficiency is displayed in Figure 2C. As the temperature increased from 30 to 60°C, the yields of all three alkaloids are slightly enhanced. However, at a higher temperature of 70°C, the yields of the alkaloids are lower, presumably owing to thermal degradation in the acidic solution. Therefore, the optimal temperature was chosen as 60°C.

Figure 2D presents the alkaloid yields obtained for a range of extraction times (1‒4 min). For isotetrandrine and cepharanthine, the yields show no significant differences, whereas for cycleanine, a slight decrease in the yield is observed both at the 1- and 4-min extraction times. It is possible that the short extraction time was insufficient for cycleanine extraction, whereas the long extraction time resulted in degradation. Therefore, an extraction time of 2 min was considered optimal.

The extraction yields under different microwave powers are shown in Figure 2E. When the microwave power increased from 75 to 100 W, no significant differences in the yields of cepharanthine are observed, whereas the yields of cycleanine and isotetrandrine increase. This suggests that the low power of 75 W cannot produce sufficient driving force for the diffusion of the two alkaloids to the solvent. However, when the power increases to 150 W, the yields of all the three alkaloids decline significantly. Probably, the high power causes rapid local heating, resulting in degradation of the target compounds. As a result, a power of 100 W was considered suitable to achieve high yields of the alkaloids while maintaining their stability.

Purification of alkaloids by SPE

The extract obtained under the optimal MAE conditions was subjected to SPE for the removal of matrix compounds. Different SPE cartridges, including Cleanert C18, Cleanert PEP, Cleanert SCX, Cleanert C8/SCX, Cleanert PCX and HR-XC, were evaluated initially. For C18 and PEP, the cartridges were conditioned with methanol followed by water, and the pH values of the MAE sample solutions were adjusted to 8 using an ammonia solution; for SCX, C8/SCX, PCX and HR-XC, the cartridges were conditioned with methanol followed by 0.01 mol/L HCl, and the sample solutions were the MAE extracts (pH 2). The optimized condition for each SPE sorbent and the respective alkaloid yields are presented in Table I.

Table I.

The Optimal SPE Conditions for Different Cartridges and the Respective Yields of Target Alkaloids

| Cartridge | SPE condition |

Extraction yielda (mg/g, mean ± SD, n = 3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Washing | Elution | Cycleanine | Isotetrandrine | Cepharanthine | |

| C18 (100 mg) | 1 mL (pH 8) | 1 mL water | 1 mL methanol | 1.165 ± 0.032 | 7.854 ± 0.244 | 1.172 ± 0.037 |

| PEP (60 mg) | 3 mL (pH 8) | 3 mL water | 3 mL methanol | 0.876 ± 0.014* | 7.279 ± 0.113* | 0.780 ± 0.019* |

| SCX (100 mg) | 3 mL (pH 2) | 3 mL water, 3 mL methanol | 3 mL methanol‒25% ammonia (97.5 : 2.5, v/v) | 1.168 ± 0.016 | 7.801 ± 0.020 | 1.187 ± 0.020 |

| C8/SCX (50 mg) | 1 mL (pH 2) | 1 mL water | 1 mL methanol‒25% ammonia (97.5 : 2.5, v/v) | 1.106 ± 0.038 | 7.398 ± 0.285 | 1.125 ± 0.052 |

| PCX (60 mg) | 3 mL (pH 2) | 3 mL water, 3 mL methanol | 3 mL methanol‒25% ammonia (97.5 : 2.5, v/v) | 1.169 ± 0.021 | 7.821 ± 0.114 | 1.184 ± 0.027 |

| HR-XC (60 mg) | 3 mL (pH 2) | 3 mL water, 3 mL methanol | 3 mL methanol‒25% ammonia (97.5 : 2.5, v/v) | 1.121 ± 0.052 | 7.494 ± 0.289 | 1.127 ± 0.041 |

aStudent's t-test was used to assess the significance of differences between treatments.

*P < 0.01 versus the PCX group.

Among the tested sorbents, Cleanert C18 and Cleanert PEP are reversed-phase sorbents based on silica and polymer, respectively. This type of sorbent is commonly used for the purification of basic, neutral and acidic compounds. Because the bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids are weak bases, the acidic MAE solution was alkalized with an ammonia solution to enhance retention of the alkaloids. Although Cleanert PEP failed to provide satisfactory alkaloid yields, Cleanert C18 provided higher yields presumably because of the lower amounts of sample and higher amounts of sorbent. However, the two sorbents share a common drawback in that the sample solution becomes slightly turbid under alkaline pH; this is probably because of decreased alkaloid solubility under these conditions. This drawback sometimes resulted in poor reproducibility or blockage of SPE cartridges in our experiments, and therefore, this kind of sorbent was not a good option.

The Cleanert SCX, Cleanert C8/SCX, Cleanert PCX and HR-XC sorbents all consist of a strong cation exchanger, which has more selectivity toward weakly basic compounds. The target alkaloids in the acidic MAE solution are in their cationic form and can be adsorbed through cation-exchange interactions. Then, water and methanol can be used to remove hydrophilic and hydrophobic interferences, respectively. Basic methanol eliminates strong ion-exchange interactions via deprotonation of ionized amine groups and reduces the nonpolar interactions between the alkaloids and the sorbent, thus eluting the analytes. Compared with the reversed-phase sorbent, this type of sorbent provides selective extraction, reproducible results and a clean extract.

Among the four sorbents with cation-exchange functionalities, Cleanert SCX and Cleanert C8/SCX are silica based, whereas Cleanert PCX and HR-XC are polymer based. The polymeric sorbents do not require wetting of the cartridge prior to sample loading, which offers the convenience of continuous vacuuming during the SPE procedure. In our experiments, the polymer-based Cleanert PCX was selected because of its lower cost compared with HR-XC.

Two washing solvent systems were compared: 3 mL of water followed by 3 mL of methanol, and 3 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl followed by 3 mL of methanol. Both systems exhibited similar results in terms of the extraction of the analytes and the elimination of the coextractives. The first system was chosen for its convenience.

Elution solvents with different percentages (2.5, 5 and 7.5%) of 25% ammonia in methanol were evaluated. All the solvents led to the complete elution of the analytes. However, methanol‒25% ammonia (97.5 : 2.5, v/v) eluted the least number of unwanted matrix compounds in the final chromatograms, achieving the best purification without loss of analytes.

Method validation for MAE–SPE–HPLC

The MAE–SPE–HPLC method was validated with regard to its specificity, linearity, sensitivity, precision, accuracy, repeatability and stability.

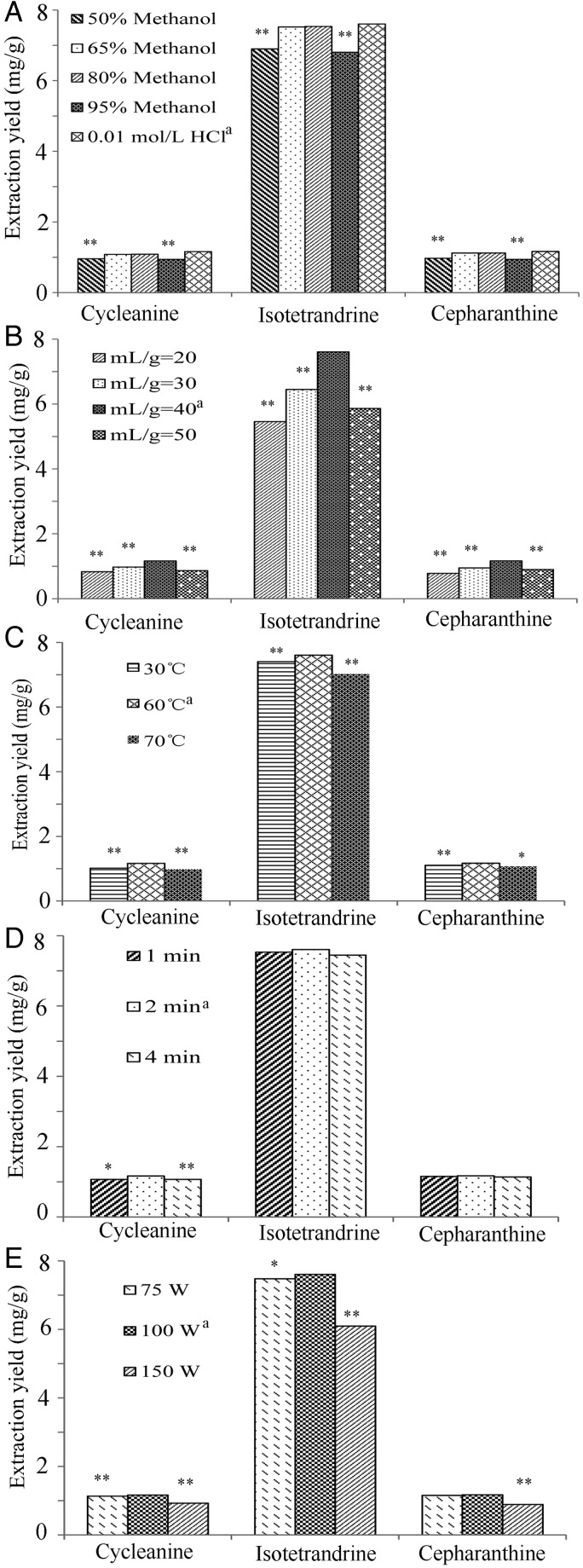

The method specificity was assessed by comparing the chromatograms of the extracts from S. cepharantha with those of alkaloid standards. The three alkaloids in the extracts were well separated with no interfering peaks, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

HPLC chromatograms of (A) a standard mixture of the three alkaloids and (B) an MAE–SPE extract of S. cepharantha. Peaks: (1) cycleanine, (2) isotetrandrine and (3) cepharanthine.

The calibration curves of the alkaloid standards were established by linear regression of peak areas (y) versus nominal concentrations (x). Each analyte showed good linearity (r > 0.9999) over the tested concentration ranges (Table II). For cycleanine, isotetrandrine and cepharanthine, the limits of detection (S/N ≥ 3) were 0.30, 0.26 and 0.20 µg/mL, respectively, and the limits of quantification (S/N ≥ 10) were 3.64, 3.13 and 2.44 µg/mL, respectively.

Table II.

Linear Ranges, Regression Equations, Correlation Coefficients and Precision Values for the Determination of Target Alkaloids in S. cepharantha

| Compound | Linear range (µg/mL) | Regression equation | r | Concentrationa (µg/mL) | Intraday precision RSD (%, n = 3) | Interday precision RSD (%, n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycleanine | 3.64‒232 | y = 7.387x − 8.207 | 0.9999 | 232.75 | 0.17 | 1.6 |

| 58.19 | 0.51 | 2.8 | ||||

| 7.27 | 0.59 | 1.5 | ||||

| Isotetrandrine | 3.13‒200 | y = 7.709x − 6.717 | 0.9999 | 200.00 | 0.23 | 2.9 |

| 50.00 | 0.45 | 2.4 | ||||

| 6.25 | 0.73 | 1.7 | ||||

| Cepharanthine | 2.44‒156 | y = 14.25x − 10.79 | 0.9999 | 156.00 | 0.21 | 1.9 |

| 39.00 | 0.52 | 2.5 | ||||

| 4.88 | 0.72 | 1.8 |

aThe three concentrations used for the evaluation of method precision.

The precision of the method was evaluated by intra- and interday analyses. Mixed standard solutions were prepared at three concentration levels. Each concentration level was analyzed in triplicate within the same day for intraday precision evaluations and on three consecutive days for interday precision evaluations. The intra- and interday relative standard deviations (RSDs) were <2.9% (Table II).

For the recovery test, the spiked sample was prepared by adding cycleanine (0.3078 mg), isotetrandrine (2.0281 mg) and cepharanthine (0.2145 mg) to 0.25 g of S. cepharantha samples. The spiked samples were extracted and purified by the MAE–SPE method, and then analyzed by HPLC. The recoveries were calculated as 100% × (determined amount in spiked samples − original amount in unspiked samples)/(amount spiked). The recoveries of cycleanine, isotetrandrine and cepharanthine were 102.12 ± 3.80, 101.25 ± 3.88 and 100.44 ± 2.82% (n = 6), respectively.

The method repeatability was evaluated by repeating the MAE–SPE pretreatment for six replicates using the S. cepharantha powder. For cycleanine, isotetrandrine and cepharanthine, the RSDs were 3.3, 0.79 and 1.7%, respectively, and the average contents in the sample were 1.220, 7.876 and 1.172 mg/g (n = 6), respectively.

To investigate the stability of the analytes in standard solutions and extracts, the mixed standard solutions at three concentration levels and the MAE–SPE extracts of S. cepharantha were kept at 4°C and analyzed at 0, 24 and 48 h. The RSDs of the standards and MAE extracts were below 2.0% within the 48-h time range, thus indicating that the analytes are stable under these testing conditions.

Overall, the validation data indicate that the MAE–SPE–HPLC method is reliable and applicable to the quantification of the three bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids in S. cepharantha.

Comparison of MAE–SPE with other sample preparation methods

During the method development, MAE, UAE and SE were investigated for their ability to rapidly extract target alkaloids from S. cepharantha, and then the crude extracts without further purification were compared with the extract prepared by the proposed MAE–SPE method.

All the above-tested extraction methods could completely extract the three alkaloids with no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the yields. Notably, the MAE method took only 2 min instead of the 7 h required for the SE method and the 30 min required for the UAE method. Therefore, the MAE method was selected for the extraction.

However, the solutions of the MAE, UAE and SE extracts were dark, and this usually resulted in a gradual increase of column pressure. MAE followed by SPE resulted in a much lighter-colored extract solution, indicating reduced amounts of coextracted compounds that may or may not appear in the chromatograms (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3); thus, the HPLC column lifetime could be significantly prolonged.

Discussion

In this study, a procedure involving efficient MAE followed by selective SPE was established for the chromatographic analysis of the alkaloids in S. cepharantha.

The MAE was highly efficient, and the extraction solvent (0.01 mol/L HCl) was simple and environmentally friendly. Moreover, the MAE method could extract up to 10 samples in a single batch. In consideration of all of these features, MAE is considered an appropriate method for the desired rapid and environmentally friendly extraction technique.

Although the proposed MAE without further SPE purification could also offer satisfactory results for the quantification, the MAE extract contained many matrix substances, which required much time for cleaning or regeneration of the HPLC columns. SPE purification on a cation-exchange polymeric cartridge selectively purified the alkaloids in the crude MAE extract. Thus, the MAE–SPE method provided a much cleaner extract, which significantly reduced the need for maintenance of chromatographic systems. Moreover, clean samples obtained by MAE–SPE will be helpful in improving the accuracy of continuous sample analyses. Therefore, the MAE–SPE method is recommended for the routine analysis of alkaloids in S. cepharantha.

Conclusion

In summary, an MAE–SPE method followed by HPLC has been developed for the simultaneous determination of three bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids in S. cepharantha. The combination of MAE and SPE produced much cleaner extracts than that obtained using MAE, UAE and SE methods alone, and thus, it could significantly prolong HPLC column lifetime. The three structurally similar alkaloids were separated successfully on a Luna phenyl-hexyl HPLC column. In comparison with previously reported approaches, the proposed MAE–SPE procedure has considerable advantages in terms of the simplicity of operation, cleanup efficiency, low organic solvent consumption and reproducibility.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Journal of Chromatographic Science online.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100238), and the project to enhance the research ability of young teachers at Fudan University (20520133180).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Editorial Committee of Flora of China; Flora of China, Volume 30 (1). Science Press, Beijing, (1996), p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang T.K., Ding Z.Q., Zhao S.X.; Modern compendium of Materia Medica. China Medical Science Press, Beijing, (2001), pp. 842–844. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashiwaba N., Morooka S., Kimura M., Ono M., Toda J., Suzuki H. et al. Stephaoxocanine, a novel dihydroisoquinoline alkaloid from Stephania cepharantha; Journal of Natural Products, (1996); 59: 803–805. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanahashi T., Su Y., Nagakura N., Nayeshiro H.; Quaternary isoquinoline alkaloids from Stephania cepharantha; Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, (2000); 48: 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otshudi A.L., Apers S., Pieters L., Claeys M., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E. et al. Biologically active bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids from the root bark of Epinetrum villosum; Journal of Ethnopharmacology, (2005); 102: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohombo-Ekomba M.L., Okusa P.N., Penge O., Kabongo C., Choudhary M.I., Kasende O.E.; Antibacterial, antifungal, antiplasmodial, and cytotoxic activities of Albertisia villosa; Journal of Ethnopharmacology, (2004); 93: 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang T.X., Yang X.H.; Reversal effect of isotetrandrine, an isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from Caulis Mahoniae, on P-glycoprotein-mediated doxorubicin-resistance in human breast cancer (MCF-7/DOX) cells; Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica, (2008); 43: 461–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haginaka J., Kitabatake T., Hirose I., Matsunaga H., Moaddel R.; Interaction of cepharanthine with immobilized heat shock protein 90α (Hsp90α) and screening of Hsp90α inhibitors; Analytical Biochemistry, (2013); 434: 202–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furusawa S., Wu J.H.; The effects of biscoclaurine alkaloid cepharanthine on mammalian cells: Implications for cancer, shock, and inflammatory diseases; Life Sciences, (2007); 80: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda K., Hattori S., Komizu Y., Kariya R., Ueoka R., Okada S.; Cepharanthine inhibited HIV-1 cell–cell transmission and cell-free infection via modification of cell membrane fluidity; Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, (2014); 24: 2115–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang H.L., Hu G.X., Wang C.F., Xu H., Chen X.Q., Qian A.D.; Cepharanthine, an alkaloid from Stephania cepharantha Hayata, inhibits the inflammatory response in the RAW264.7 cell and mouse models; Inflammation, (2014); 37: 235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou E.S., Fu Y.H., Wei Z.K., Cao Y., Zhang N.S., Yang Z.T.; Cepharanthine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced mice mastitis by suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway; Inflammation, (2014); 37: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uto T., Nishi Y., Toyama M., Yoshinaga K., Baba M.; Inhibitory effect of cepharanthine on dendritic cell activation and function; International Immunopharmacology, (2011); 11: 1932–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Z.Y., Feng Y.X., He L.Y., Wang Y.C.; Utilization of medical plant resources of the genus Stephania of the family Menispermaceae in China; Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica, (1983); 18: 460–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruan D.C., Zhang X.M., Zhao C.J., Wang F.C., Tian L.X., Yang C.R.; High performance liquid chromatographic analysis of alkaloids in Stephania plants; Acta Botanica. Yunnanica, (1991); 13: 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J.M., Guo J.X., Duan G.L.; Determination of 7 bio-active alkaloids in Stephania plants by RP-HPLC; Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica, (1998); 33: 528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Q.H., Liu Y.P., Wang X., Di X.; Microwave-assisted extraction in combination with capillary electrophoresis for rapid determination of isoquinoline alkaloids in Chelidonium majus L; Talanta, (2012); 99: 932–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y., Zeng R.J., Lu Q., Wu S.S., Chen J.Z.; Ultrasound/microwave-assisted extraction and comparative analysis of bioactive/toxic indole alkaloids in different medicinal parts of Gelsemium elegans Benth by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with MS/MS; Journal of Separation Science, (2014); 37: 308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan Z.Q., Xiao X.H., Li G.K.; Dynamic pH junction high-speed counter-current chromatography coupled with microwave-assisted extraction for online separation and purification of alkaloids from Stephania cepharantha; Journal of Chromatography A, (2013); 1317: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu H.Y., Feng Y.G., Yang J., Pan W.J., Li Z.H., Tu Y.G. et al. Separation and characterization of sucrose esters from Oriental tobacco leaves using accelerated solvent extraction followed by SPE coupled to HPLC with ion-trap MS detection; Journal of Separation Science, (2013); 36: 2486–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandes V.C., Domingues V.F., Mateus N., Delerue-Matos C.; Determination of pesticides in fruit and fruit juices by chromatographic methods. An overview; Journal of Chromatographic Science, (2011); 49: 715–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun S.W., Kuo C.H., Lee S.S., Chen C.K.; Determination of bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids by high-performance liquid chromatography (II); Journal of Chromatography A, (2000); 891: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y.Q., Yin J.J., Xie D.T., Kang Y., Weng W.Y., Huang J.M.; Determination of cepharanthine in Stephania cepharantha Hayata by MSPD–HPLC; Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine, (2014); 36: 2557–2560. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Li H.F., Ma Y., Jin Y., Kong G.H., Lin J.M.; Microwave assisted extraction–solid phase extraction for high-efficient and rapid analysis of monosaccharides in plants; Talanta, (2014); 129: 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watterson J.H., Imfeld A.B., Cornthwaite H.C.; Determination of colchicine and O-demethylated metabolites in decomposed skeletal tissues by microwave assisted extraction, microplate solid phase extraction and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (MAE–MPSPE–UHPLC); Journal of Chromatography B, (2014); 960: 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotnik K., Kosjek T., Krajnc U., Heath E.; Trace analysis of benzophenone-derived compounds in surface waters and sediments using solid-phase extraction and microwave-assisted extraction followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry; Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, (2014); 406: 3179–3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.