Abstract

Introduction

As the average age of haemodialysis patients rapidly increases around the world, the number of frail, elderly patients has increased. Frailty is well known to be an indicator of disability and a poor prognosis for haemodialysis patients. Exercise interventions have been safely and successfully implemented for middle-aged or younger patients undergoing haemodialysis. However, the benefits of exercise interventions on elderly patients undergoing haemodialysis remain controversial. The main objective of this study is to systematically review the effects of exercise training on the physical function, exercise capacity and quality of life of elderly patients undergoing haemodialysis, and to provide an update on the relevant evidence.

Methods and analyses

Published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed the effectiveness of exercise training on haemodialysis patients with respect to physical function, exercise tolerance and quality of life will be included. Bibliographic databases include MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsycINFO and PEDro. The risk of bias of the included RCTs will be assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool and TESTEX. The primary outcome will be physical function and exercise tolerance. This review protocol is reported according to the PRISMA-P 2015 checklist. Statistical analysis will be performed using review manager software (RevMan V.5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required because this study does not include confidential personal data nor does it perform interventions on patients. This review is expected to inform readers on the effectiveness of exercise training in elderly patients undergoing haemodialysis. Findings will be presented at conferences and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42015020701.

Keywords: Elderly, Frailty

Introduction

The world population continues to age. In 2015, there were 901 million people aged 60 years or above, comprising 12% of the global population. Approximately one-in-four people in Japan are elderly.1 Japan today has the lowest potential support ratio in the world, which is defined as the number of people aged 20–64 years divided by the number of people aged 65 years and over.2 It is therefore important for elderly people to live an independent life in Japan.

The incidence of chronic kidney disease leading to renal replacement therapy such as haemodialysis is increasing worldwide because of an ageing population and the higher prevalence of lifestyle-related illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease.3 As a result of the improved survival of dialysis patients and the reduced access to transplants for elderly patients, the mean age of the dialysis population continues to increase over time. In the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study, which studied an international cohort consisting of participants from 12 countries, significant age increases in dialysis patients were observed in those from almost all included nations.4 Other data from the USA and Europe also note a high proportion of elderly dialysis patients.5 6 The Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy has been conducting a statistical survey of dialysis facilities across the country annually since 1968. Although the number of new Japanese dialysis patients each year is trending downwards, the total number of dialysis patients is gradually increasing. The mean age of Japanese dialysis patients is 66.9 years and has increased by 11.6 years from the end of 1991 to the end of 2012. Furthermore, the proportions of elderly patients over 60 years among the patients started on dialysis in 2012 and in all dialysis patients were 78.1% and 75.4%, respectively.7

Most elderly patients on haemodialysis are frailer than non-elderly patients, and frailty is well known to be an indicator of disability and a poor prognosis in dialysis patients.8 9 Exercise training is therefore in great need for elderly patients on haemodialysis. Although prior meta-analyses have already reported on the effectiveness of exercise interventions on the physical function, exercise capacity and quality of life of patients undergoing haemodialysis,10 11 these analyses did not consider whether their participants were elderly. Exercise intervention for elderly patients on haemodialysis is complex and controversial, and how to best manage these patients is poorly understood in the nephrology community. Furthermore, it is unclear whether exercise training improves the physical function, exercise capacity or quality of life of elderly patients on haemodialysis. We need to analyse the effectiveness of exercise interventions on these outcomes while taking into consideration the patient's age. Additionally, because new trials for elderly patients undergoing haemodialysis continue to be published in this area,12 13 the evidence regarding the effectiveness of exercise training on haemodialysis patients must be updated using latest data. Thus cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials facilitates the determination of clinical efficacy and harm, and may be helpful in making clinical recommendations for therapy.14

The main objective of this study is to systematically review the effects of exercise training on the physical function, exercise capacity and quality of life of elderly patients on haemodialysis, and to provide an update on the relevant evidence. This systematic review and meta-analysis protocol is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) 2015 checklist.15 16

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015020701). The study protocol will be conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.

Literature review

Our electronic database search includes MEDLINE (from 1950 to August 2015), Embase (from 1974 to August 2015), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (from start to August 2015), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (from 2005 to August 2015), CINAHL (from 1981 to August 2015), Web of Science (from 1900 to August 2015), PsycINFO (from 1806 to August 2015) and PEDro (from start to August 2015). We detail the electronic search strategy in table 1, using MEDLINE as an example. We used the following terms: dialysis, kidney failure, renal replacement therapy, exercise, rehabilitation, physical fitness, cycling, walking, physical therapy, random and so on. Supplement 1 discusses the search strategy in more detail. We also plan to evaluate the reference lists of previously reported systematic reviews in addition to our electronic database search.

Table 1.

Search strategy to be used for the MEDLINE electronic database

| Database | Search terms | |

|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE 1946–present (Ovid) |

1 | exp Ultrafiltration/ or exp kidney failure, chronic/ or exp peritoneal dialysis, continuous ambulatory/ or exp renal replacement therapy/ or exp kidney transplantation/ or exp renal dialysis/ or exp renal insufficiency/ or exp kidney diseases/ or exp kidney diseases, cystic/ or exp glomerular filtration rate/ or exp nephrology/ |

| 2 | (hemodialysis or hemofiltration or hemodiafiltration).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 3 | dialysis.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 4 | (PD or CAPD or CCPD or APD).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 5 | (kidney disease* or renal disease*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 6 | (renal insufficiency or kidney failure or renal failure).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 7 | (end-stage kidney or end-stage renal or endstage kidney or endstage renal).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 8 | (CKF or CKD or CRF or CRD or ESRF or ESKF or ESRD or ESKD).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 9 | (predialysis or pre-dialysis).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 10 | (nephropath* or nephrit* or glomerul*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 11 | (ur*emi*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 12 | (kidney transplant* or renal transplant*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 13 | or/1-12 | |

| 14 | exp Exercise/ or exp Exercise Therapy/ or exp Exercise Movement Techniques/ or exp ‘Physical Education and Training’/ or exp ‘Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine’/ or exp Physical Fitness/ or exp Sports Medicine/ or exp Sports/ or exp Sports for Persons with Disabilities/ or exp Rehabilitation Nursing/ or exp Rehabilitation Centers/ or exp Rehabilitation/ or exp Physical Exertion/ or exp Motor Activity/ or exp Movement/ or exp Sedentary Lifestyle/ or exp tai ji/ or exp yoga/. | |

| 15 | exercis*.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 16 | fitness.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 17 | (cycling or ergometer).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 18 | (walk* or treadmill).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 19 | aerobic*.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 20 | (physical fit* or physical condition* or physical education or physical train* or physical mobility or physical activit* or physical exertion or physical effort).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 21 | (physical therap* or physiotherap*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 22 | (strength* train* or aerobic train* or exercise* train*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 23 | (muscle strengthening or muscular strength or muscular resistance).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 24 | (weight lift* or weights lift* or weightlifting or power lifting or weight training).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 25 | kinesi*.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 26 | (training course* or training program*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 27 | (rehabilitat*).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 28 | or/14–27 | |

| 29 | exp controlled clinical trial/ or exp randomized controlled trial/ | |

| 30 | (randomi?ed or placebo* or randomly or trial or RCT or control groups).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 31 | or/29-30 | |

| 32 | 13 and 28 and 31 |

bmjopen-2015-010990supp.pdf (269.6KB, pdf)

Study selection/data management

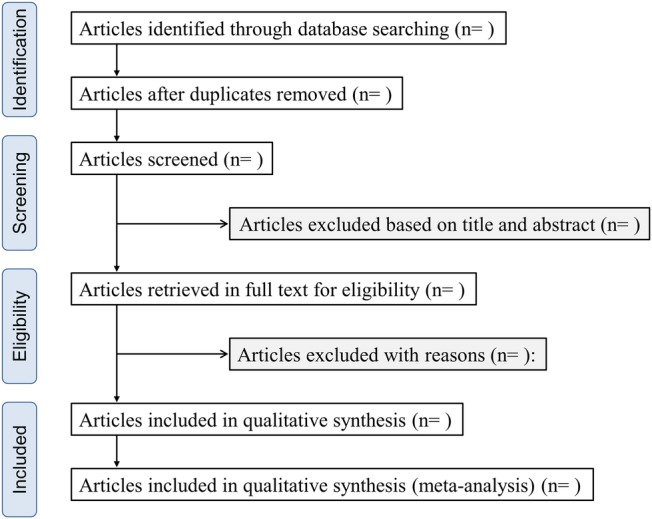

We will use EndNote V.X7 for Windows (Thompson Reuters, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) to manage literature records and data. The literature search results will be imported into EndNote. Reviewers will screen all titles, abstracts and full texts, and sort out the sources into different folders on the software. This process will be run and completed by two independent reviewers. The study selection process is described in a flow chart (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We will include studies retrieved in our literature search that meet the following criteria:

Language: published in English.

Participants: patients aged at least 18 years with chronic kidney disease and undergoing maintenance haemodialysis therapy will be included. Patients under 18 years or those undergoing any other renal replacement therapy will be excluded. Patients affected by acute kidney failure will also be excluded.

Study design: only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effects of exercise training on at least physical function will be included. Additionally, RCTs reported as systematic reviews will be read and added to our analysis in cases of any oversight. Narrative reviews, opinion papers, letters, meeting abstracts and any publications without primary data or an explicit description of the methods will be excluded.

Interventions: supervised exercise including resistance training, aerobic exercise or combined exercise will be included. Abnormal types of exercise will be excluded.

Controls: usual, non-exercise care or a limited inclusion of low-intensity exercises such as stretching.

Outcomes: physical functions (muscle strength, sit-to-stand test), walking ability (gait speed, 6 min walk test and shuttle walk test), exercise tolerance (peak oxygen intake), activities of daily living and health-related quality of life (the 36-item short form health survey and kidney disease quality of life).

Others: in the case of duplicate publication of the same study or papers published in more than one journal, the most comprehensive report will be used.

Data extraction

Relevant study characteristics and clinical outcome measures will be extracted. The data extracted from RCTs include: (1) authors; (2) publication year; (3) location; (4) mean age; (5) mean duration of dialysis therapy; (6) study design; (7) sample size of the intervention and control groups; (8) duration of intervention; (9) type of intervention; (10) training programme (frequency, exercise time, and intensity, etc); (11) treatment outcome measures obtained, including physical function, exercise tolerance, activities of daily living and quality of life. The data will be standardised (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of findings for included randomised-controlled trials

| Studies | Year | Location | Population | Mean age | Mean duration of dialysis therapy | Duration of intervention | Type of intervention (Ex group) | Type of intervention (Con group) | Training programme | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT 1 | ||||||||||

| RCT 2 | ||||||||||

| RCT 3 | ||||||||||

| RCT 4 | ||||||||||

| RCT 5 | ||||||||||

| … |

RCT, randomised-controlled trial.

Statistical analysis

Our primary outcomes will be physical function and exercise tolerance. Secondary outcomes will be: activities of daily living and quality of life. Outcome definitions will be based on those used in the included studies. We will conduct the subgroup analysis based on whether study subjects are elderly or non-elderly. Here we define elderly as those patients aged 60 years and older. If there is no study that recruited only patients aged 60 years and over, we determine elderly based on mean age in treatment group of each study. We will also conduct subgroup analyses to identify comorbidities and training programmes that may be confounding factors.

Our statistical analysis strategy will involve finding the average absolute change in included patient measures from baseline to end point (including 95% CIs) in the intervention and control groups. Effect consistency across studies will be assessed with the I2 statistic.17 I2 values >25% and 50% are considered to be indicators of moderate and substantial heterogeneity, respectively. As a result of the expected clinical heterogeneity between studies, we will use the random-effects model as the default method of analysis. This is because the alternative fixed-effect model assumes that the true treatment effect of each trial is the same, and that observed differences are due to chance. Publication bias will be assessed by plotting the inverse of the SEs of the effect estimates using funnel plots, to explore symmetry, which will be assessed visually and with the Egger's regression test. Analysis will be conducted on Review Manager Software (RevMan V.5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England). Two reviewers will independently assess the risk of study bias using the Cochrane Collaboration tool,18 which consists of the following six items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, participant and personnel blinding, outcome assessment blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other source of bias. Two reviewers will also assess the risk of bias of all references using the Tool for the assEssment of Study qualiTy and reporting in EXercise,19 which consists of 15 different items and has been found to be a reliable tool for performing a comprehensive review of exercise training trials. Furthermore, we will also assess the quality of the evidence associated with the result of each meta-analysis, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach,20–24 which gives an indication of the confidence that can be placed in the estimate of the effect of treatment.

Ethics and dissemination plans

No ethical approval is required because this study does not include confidential personal data and does not involve patient intervention. This review is expected to determine the effectiveness of exercise training on elderly patients on haemodialysis. Findings will be presented at conferences and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors: RM and AM conceived and designed the protocol. RM and KH developed the search strategy and pilot searched the database. RM, KH and KY contributed to the development of the review protocol, selection criteria, the risk of bias assessment strategy and the data extraction criteria. All the authors critically revised and commented on the intellectual content of this manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 16K16466) and a Kitasato University research grant to Atsuhiko Matsunaga.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications website (http://www.stat.go.jp/english/index.htm): 2013.

- 2.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: the 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. Working paper No. ESA/P/WP. 241 2015.

- 3.Hamer RA, El Nahas AM. The burden of chronic kidney disease. BMJ 2006;332:563–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canaud B, Tong L, Tentori F et al. . Clinical practices and outcomes in elderly hemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1651–62. 10.2215/CJN.03530410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jager KJ, van Dijk PC, Dekker FW et al. . The epidemic of aging in renal replacement therapy: an update on elderly patients and their outcomes. Clin Nephrol 2003;60:352–60. 10.5414/CNP60352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ et al. . Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:177–83. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakai S, Hanafusa N, Masakane I et al. . An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (as of 31 December 2012). Ther Apher Dial 2014;18:535–602. 10.1111/1744-9987.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzawa R, Matsunaga A, Wang G et al. . Habitual physical activity measured by accelerometer and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7:2010–6. 10.2215/CJN.03660412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuzawa R, Matsunaga A, Wang G et al. . Relationship between lower extremity muscle strength and all-cause mortality in Japanese patients undergoing dialysis. Phys Ther 2014;94:947–56. 10.2522/ptj.20130270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smart N, Steele M. Exercise training in haemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16:626–32. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training in adults with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:383–93. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsufuji S, Shoji T, Yano Y et al. . Effect of chair stand exercise on activity of daily living: a randomized controlled trial in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 2015;25:17–24. 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groussard C, Rouchon-Isnard M, Coutard C et al. . Beneficial effects of an intradialytic cycling training program in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2015;40:550–6. 10.1139/apnm-2014-0357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau J, Antman EM, Jimenez-Silva J et al. . Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1992;327:248–54. 10.1056/NEJM199207233270406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Green S eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smart NA, Waldron M, Ismail H et al. . Validation of a new tool for the assessment of study quality and reporting in exercise training studies: TESTEX. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:9–18. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1283–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence—indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1303–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence—inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1294–302. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V et al. . GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1277–82. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G et al. . GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:407–15. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010990supp.pdf (269.6KB, pdf)