Abstract

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the health condition that carries the greatest disability burden worldwide; however, there is only modest support for interventions to prevent LBP. The aim of this trial is to establish the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group-based exercise and educational classes compared with a minimal intervention control in preventing recurrence of LBP in people who have recently recovered from an episode of LBP.

Methods and analysis

TOPS will be a pragmatic comparative effectiveness randomised clinical trial with a parallel economic evaluation combining three separate cohorts (TOPS Workers, TOPS Primary Care, TOPS Defence) with the same methodology. 1482 participants who have recently recovered from LBP will be randomised to either a comprehensive exercise and education programme or a minimal intervention control. Participants will be followed up for a minimum of 1 year. The primary outcome will be days till recurrence of LBP. Effectiveness will be assessed using survival analysis. Cost-effectiveness will be assessed from the societal perspective.

Ethics and dissemination

This trial has been approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (ref: 2015/728) and prospectively registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ref: 12615000939594). We will also obtain ethics approval from the Australian Defence Force HREC. The results of this study will be submitted for publication in a prominent journal and widely publicised in the general media.

Trial registration number

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ANZCTR) 12615000939594.

Keywords: exercise, prevention, education, randomised clinical trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This will be a large, high-quality randomised controlled trial investigating exercise and education for the prevention of low back pain.

We will monitor compliance with the intervention, adverse events, and be the first to include a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Owing to the use of time-to-event data, the analysis will not consider the duration of a participant's episode of low back pain. It will also not discriminate between a moderate or severe recurrence.

Introduction

When disease is measured in terms of years lived with disability,1 low back pain (LBP) is the health condition that carries the greatest burden worldwide. With a point prevalence of 18.3%2 and half of those with LBP expected to seek care,3 the economic burden is enormous. The direct annual costs of treatment in Australia are estimated to be $1 billion with a further $8 billion spent on indirect costs.4 Studies of the course of LBP5–7 have shaped the contemporary view that LBP is typically a long-term health condition with an unpredictable pattern of symptomatic episodes, remission and recurrence.8 9 The recurrent nature of LBP is a major reason why the condition carries such a large social and economic burden around the world,9 with the 1-year recurrence rates reported in the literature ranging from 25 to 80%.10–12 Despite the impact of these LBP recurrences, we have very little understanding of why this pain recurs the only known predictor of recurrence being the number of previous occurrences.12

In the general community there are widely held beliefs about ‘what’ things are ‘bad’ for backs, and also about what one should do to prevent recurrences of LBP. There are a wide range of health services, remedies and devices marketed to prevent back pain. However, in stark contrast to the community's belief about LBP prevention, the latest systematic review13 on the topic suggests that only exercise alone or in combination with education is effective with a 35% and 45% reduction, respectively, in the recurrence rate of LBP up to 1 year. While the results of this systematic review are promising, it also has a number of limitations. Though this systematic review was based on 21 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with 30 850 unique participants, the trials which informed the exercise, and exercise and education analyses were generally small, unregistered, and did not attend to trial features such as concealed allocation, blinding and intention-to-treat analysis. Therefore, these are likely to provide exaggerated estimates of treatment effects. Also none provided any information on cost-effectiveness. Accordingly, there is insufficient information for clinicians to confidently advise their patients on the likelihood of benefits and harms, and for health policy makers to judge whether exercise programmes to prevent recurrences of LBP represent value for money and are a wise investment.

The aim of this trial, TOPS (Trial Of Prevention Strategies for low back pain in patients recently recovered from LBP), is to establish the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group-based exercise and education classes compared with a minimal intervention control in preventing recurrence of LBP in people who have recently recovered from an episode of LBP. We will also establish the risk of adverse events (AEs), and monitor a number of process outcomes, such as physical activity levels and back pain beliefs, in order to determine the mechanisms through which any protective intervention might act. A safe, cost-effective intervention to prevent recurrences of LBP would be of enormous benefit to individuals and society. If we are able to show strong evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these programmes, it will help strengthen the engagement not just from individuals and care providers, but also from employers and the government.

Methods and analysis

Design overview

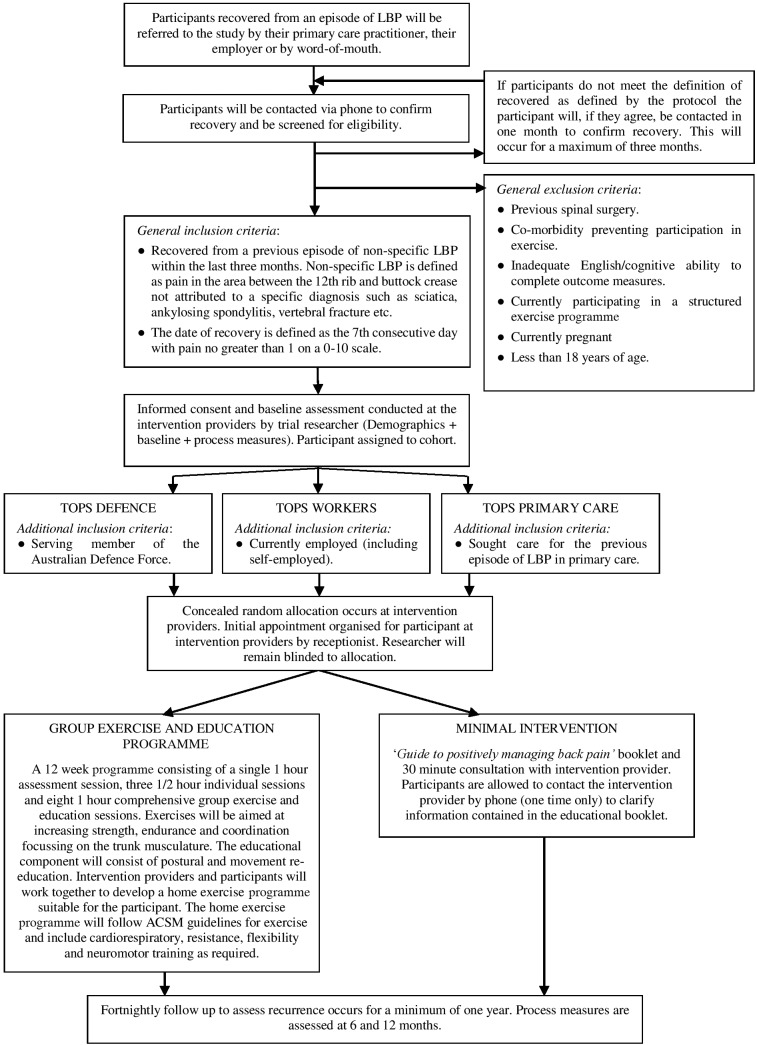

TOPS will be a pragmatic comparative effectiveness randomised clinical trial with a parallel economic evaluation combining three separate cohorts (TOPS Workers, TOPS Primary Care, TOPS Defence), pending funding approval, with the same methodology. In this trial, 1482 participants who have recently recovered from LBP will be randomised to either a comprehensive exercise and education programme or a minimal intervention control. Participants will be followed up for a minimum of 1 year, with the total length of the trial dependent on funding. The primary outcome will be days till recurrence of LBP. The overall design is illustrated in figure 1. The protocol is reported in accordance with SPIRIT14 (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials), TIDieR15 (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) and CERT16 (Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template) statements.

Figure 1.

Study design. ACSM, American College of Sports Medicine; LBP, low back pain.

Participants

Potential participants will be referred to the study on recovery from an episode of LBP. This referral may occur through the participant's primary care practitioner (general practitioner (GP) or physiotherapist), through their employer or through self-referral. A researcher will contact potential participants referred to TOPS to confirm recovery. If participants referred to the study do not meet the definition of ‘recovered’ as defined in this protocol they will, if they permit, be contacted 1 month later to reassess if they have recovered. This will occur for a maximum of 3 months. After recovery has been confirmed, participants will be fully informed about the study and all eligibility criteria will be checked. Participants will then attend a baseline assessment with a researcher where they will give written informed consent, and demographics and baseline data will be collected.

Eligibility criteria

Participants will be included if they meet the following inclusion criteria:

Recovered from an episode of non-specific LBP within the past three months. Non-specific LBP is defined as pain in the area between the 12th rib and buttock crease not attributed to a specific diagnosis (infection, malignancy, spondyloarthritis, vertebral fracture, etc) and not accompanied by radicular pain attributable to a true nerve compression. The date of recovery is defined as the seventh consecutive day with average pain no >1 on a 0–10 scale.

TOPS Workers participants must also be currently employed (including self-employed).

TOPS Defence participants must be serving members of the Australian Defence Force (including reserve/part-time members).

TOPS Primary Care participants must have sought care for the previous episode of LBP in primary care.

Participants will be excluded if they have any of the following:

Previous spinal surgery.

Any co-existing medical condition that would restrict or prevent safe participation in the exercise programme, for example, uncontrolled hypertension.

Inadequate English/cognitive ability to provide consent and complete outcome measures.

Currently participating in (1) an exercise programme similar to the one we will evaluate, or (2) a structured moderate intensity aerobic exercise for at least 150 min/week, or (3) a structured strength training exercise programme at least two times/week.

Unable to collect valid baseline physical activity data (wearing time of at least 10 hours/day on at least 4 days of the 7-day wearing period)

Currently pregnant.

Less than 18 years of age.

Randomisation

Immediately after baseline data have been collected and checked, participants will be randomly allocated to treatment group in a 1:1 ratio. The randomisation schedule will be generated prior to the start of the trial by an independent investigator using a permuted blocking method with random block sizes. Consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes will be used to conceal randomisation. Randomisation will be stratified for each cohort TOPS Workers, TOPS Defence and TOPS Primary Care and by the participants' history of LBP (more than two previous episodes; yes/no). The participant will be considered as ‘entered’ into the trial at the point of randomisation.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the trial, it will not be possible to blind participants or intervention providers. However, in an effort to blind the participants as much as possible to the trial research question, it will be explained that the study compares two methods for preventing recurrence of back pain. Researchers collecting follow-up data and conducting the analysis will remain blinded to treatment allocation.

Intervention

Intervention providers will be registered physiotherapists experienced in the conduct of exercise programmes for LBP and located at various private practices throughout the greater Sydney area. These providers have been chosen as they represent clinicians with already established group exercise programmes designed to prevent LBP; therefore, the findings of this study will be reflective of clinical practice. Participants will begin their intervention within 1 week of enrolment.

Minimal intervention

Participants will receive the ‘Guide to Positively Managing Back Pain’ booklet17 and one half-hour appointment with the intervention provider where they will be taken through the booklet and have it explained to them. Included in this time will be opportunity for the participant to ask any questions they might have about the booklet or its contents. Participants will have the opportunity to contact the intervention provider by phone on one occasion after the end of the session to clarify the information contained in the booklet or ask further questions. In order to maintain the minimalist nature of this intervention, the providers conducting the intervention cannot volunteer information that goes beyond the scope of the booklet.

The ‘Guide to Positively Managing Back Pain’ booklet has been developed by a private health insurance company in Australia (BUPA), and the company has given approval for its use in this study. It is a publicly available resource that includes advice on self-management and prevention of back pain, as well as a brief overview of the various types of exercise. This booklet has been chosen as it provides information that is already available to the general public; thus, providing this information to the participant represents no practical increase in the level of education available when compared to what is accessible to a member of the general population.

Group exercise and education programme

Participants in the group exercise and education programme will receive a comprehensive individualised exercise and education programme over 12 weeks. This includes a single 1-hour individual assessment session prior to the start of the programme, three individual half-hour progress assessment sessions at 4, 8 and 12 weeks, and 8 supervised group exercise sessions from weeks 1–8. The purpose of the individual assessment sessions is to enable the intervention provider to determine the most appropriate level (quantity and intensity) and type of exercises for the participant. Mandated diagnostic tests to occur in the initial assessment are presented in table 1, with further tests conducted at the provider's discretion. Progress assessments have no mandated tests, rather the provider will reassess those measures deemed important in the previous assessment session. Also within the assessment sessions will be time for the prescription of the home exercise programme. The home exercise programme will build on the exercise conducted within the sessions, and facilitate continuance of exercises once the supervised group exercise programme has been completed. The group exercise sessions will be conducted once per week with a ratio of between 3 and 8 participants per intervention provider and will run for 1 hour. After completion of the final progress assessment, weekly education and/or motivational tips will be sent to the participants via phone (short message service; SMS) or email according to the participant's preference for another 12-week period.

Table 1.

Specific diagnostic tests to be completed in the initial assessment session

| Assessment type | Assessment |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | STEP (Step Test and Exercise Prescription)19 |

| Muscular endurance | Ito extensor endurance test20 Trunk-flexor endurance test (partial sit-up)21 |

| Muscle flexibility/ mobility: | Thomas test (hip flexors)22 Standing forward bend23 Active knee extension test (hamstring length)24 |

| Neuromotor fitness | Posture (sitting and standing) Squat25 1 leg squat |

The exercises/activities implemented as a part of this intervention will be at the provider’s discretion and focus on four key areas of exercise training identified by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM).18 These are: cardiorespiratory, resistance, flexibility and neuromotor exercise. All participants will be directed to meet the ACSM's guidelines for cardiorespiratory exercise. Specific resistance, flexibility and neuromotor exercises which emphasise performance of functional everyday activities will be prescribed according to areas of deficit identified in the initial and progress assessments. Intervention providers will work with participants to provide an individualised and graded exercise programme that reflects the participant's physical capacity and the nature of work, household, social and sporting activities the participant is involved in. The progression of the programme will conform to the ACSM's position statement.18

Equipment such as hand-held weights, resistance bands or instability platforms may be used to provide variable resistance or progress the exercises. If exercise equipment needs to be purchased for conduct of the home exercise programme, participants will be reimbursed up to AU$50. Intervention providers will make sure not to prescribe exercises requiring equipment that the participant does not have access to or ability to purchase.

The educational component will consist of a number of elements: a basic understanding of anatomy and kinesiology, postural and movement education, causes and management of LBP, benefits of exercise and motivational ideas. The educational components will be delivered in two ways. The first will be conducted as part of the group classes, and integrated with the provision of exercises such that as the participant learns to perform the exercise they are also learning the theory behind what they are doing and why it is important to them. This will help in retaining the key principles of both the exercise and the educational components, and assist in self-identification of any possible deconditioning that may occur after the exercise programme has been completed. The second will be conducted from weeks 14 to 26 with the purpose of reinforcing the educational information received in the classes and maintaining compliance with the exercise programme beyond completion of the 12-week programme. These messages will be delivered by SMS or email at the participant's preference once a week.

Follow-up

From enrolment into the programme the participants will be followed up every 2 weeks by SMS or email (according to participant's preference) until completion of the study. At each follow-up participants will be asked whether they have had a recurrence of their LBP in the past 2 weeks. Participants followed up via SMS will be able to respond with either a ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If the participant indicates they have had a recurrence of LBP, they will receive a phone call from the researcher to collect details of the recurrence. At this time, the researcher will also arrange for a cost diary to be mailed out to the participant enabling them to maintain a record of costs occurred as a consequence of their LBP. Follow-ups through email will consist of an online survey to determine whether or not the participant has had a recurrence of LBP. If the participant responds with a ‘yes’, the survey will automatically ask further details of the recurrence. A cost diary will also be mailed out. Further outcomes collected at 14 weeks, 6 months and 12 months will be collected along with normal recurrence data by either phone or online survey.

All online surveys will be conducted on a database specifically designed for the study using the REDCap software. All SMS follow-ups will be conducted using SMS Global. Any participant who has not responded to the survey after 48 hours will be followed up by phone. The researcher will attempt to contact the participant three times over the next 72 hours, including leaving messages. If the researcher is able to contact the participant, they may then conduct the survey by phone if convenient to the participant.

Study outcomes

Primary outcome

Days to recurrence of an episode of LBP (defined as back pain lasting for at least 24 hours with a pain intensity of 3 or more on a 0–10 numeric pain rating scale).

Secondary outcomes

Days to recurrence of:

An episode of LBP resulting in work absence of at least 1 day (for those in paid employment);

An episode of consulting for LBP (with consultation to a healthcare provider);

An episode of activity-limiting LBP (moderate or greater activity limitation measured using an adaptation of item 8 of the SF-36).

Cost outcomes

Outcomes used for the cost-effectiveness analysis include:

Hours taken off normal paid work;

Use of healthcare services including type (eg, GP and physiotherapist) and number of uses;

Use of community or other services (eg, gym attendance and meals on wheels);

Use of prescription medicine (name, strength, tablets/day and number of days);

Use of over-the-counter medication or other out-of-pocket costs (eg, purchase of a lumbar belt).

Process measures

Process measures will be collected at baseline, 6 and 12 months. These are physical activity levels and back pain beliefs. These measures have been chosen as we feel these areas will inform the results of the study by helping us understand the mechanisms of action through which any potential benefit may act. Physical activity will be objectively assessed with the Actigraph GT3X-Plus accelerometer. It records activity counts and steps taken, which are converted to time spent in sedentary, light, moderate and vigorous intensity physical activity using established cut points based on activity counts per minute. The Actigraph is a non-invasive, small, lightweight device (4.6×3.3×1.5 cm, 19 g) that is worn during waking hours for seven consecutive days on the right hip. The Actigraph is the most researched accelerometer in the physical activity and health field over the past 15 years, and has been shown to be the most valid.26 Beliefs about back pain will be measured using the Back Beliefs Questionnaire, a validated 14-item self-report questionnaire used to quantify beliefs about the likely consequences of having LBP.27

Intervention compliance and treatment credibility

Compliance with the home exercise programme will be measured using a Study Diary. The diary will be given to the physiotherapist and used for recording details of the assessment session, the home exercise programme, and adherence to the intervention. The diary will be returned to the researcher after the intervention has been completed. Treatment credibility will be assessed at 14 weeks using a modified version of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire.28

Adverse events

AEs will be measured via a questionnaire at 14 weeks (the first follow-up following completion of the intervention). An AE is any untoward medical occurrence in a participant temporarily associated with the trial intervention, whether or not it is considered related to the trial intervention. A serious AE (SAE) is one that is life-threatening or requires inpatient hospitalisation or will result in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, and these will have to be reported immediately.

Statistical analysis

The primary analyses will be by intention-to-treat. It is hypothesised that group-based exercise and education classes will be effective and cost-effective compared to a minimal intervention in preventing recurrence of LBP.

Primary outcome analysis

We will assess difference in survival curves (days to recurrence of episode LBP) using the log-rank statistic. Cox regression will be used to assess the effect of treatment group on HRs. We have stratified for the only known predictor of recurrence (previous recurrence).12 We will treat prognostic factors for back pain29 30 as potential confounders; if these are unbalanced despite randomisation, we will include them as covariates in the analysis. The proportional hazards assumption will be tested using the time-dependent covariate method. For the secondary outcomes, an analogous survival analysis will be conducted. For the primary outcome, a p value of <0.05 will be considered statistically significant. For the secondary outcomes, a p value of <0.01 will be considered significant.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The cost-effectiveness analysis will be conducted from the societal perspective and according to the intention-to-treat principle. It will compare group exercise to minimal intervention using the primary outcome as the measure of effectiveness. Costs of the study treatment will be derived from the cost of providing the intervention plus the cost of equipment purchased. Costs to the healthcare system incurred due to back pain recurrences will be valued at standard rates published by the Australian Government (eg, Medical Benefits Scheme standard fees, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme cost for medications). Costs of the study treatments and private non-medical healthcare services (eg, physiotherapy) will be valued at standard rates published by the relevant professional body or third party payer. Costs of community services (eg, gym attendance) and other out-of-pocket costs (eg, purchase of a lumbar belt) will be based on the self-reported costs of participants. The costs of work absenteeism will be estimated by the number of days absent from work multiplied by the average wage rate. Presenteeism (ie, lost performance while at work) will be measured using an item of the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ) asking workers to rate their overall work performance during the previous four weeks on a 11-point scale, ranging from ‘worst performance’(0) to ‘best performance’(10).31

An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio will be calculated by dividing the between-group difference in costs by the between-group difference in effects (ie, costs per recurrence-free month gained). Cost-effectiveness ratios will be estimated using bootstrapping techniques (5000 replications), and graphically presented on cost-effectiveness planes. Acceptability curves and net monetary benefit will also be estimated. Sensitivity analyses on the most important cost drivers will be performed in order to assess the robustness of the results.

Sample size

Each cohort has been independently powered to detect a clinically significant result for the primary outcome. Sample size was calculated for the primary outcome using PASS software based on the method of Lakatos32 by means of a two-sided log rank test with an α value of 0.05. For TOPS Workers, we calculated that a sample size of 80 participants per group will give 80% power to detect a 40% relative reduction in recurrence rates between the treatment group and the control group. For TOPS Defence, 150 participants per group will provide 80% power to detect a 30% relative reduction between treatment groups; for TOPS Primary Care, 511 participants per group will provide 80% power to detect a 20% relative reduction between groups. Pooling the data from all 1482 participants will provide 80% power to detect a 15% relative reduction between the treatment groups. These calculations are based on 30% recurrence in 1 year in the control group, a rate we observed in our recent study.12 Higher rates of recurrence typically reported in the literature would increase power.10–12 We have allowed for 1% loss to follow-up, and 1% treatment non-compliance per month in both groups.

Data management

Data will be maintained and stored using the REDCap database software using a combination of data collection and entry by researchers, and automatic entry by the participants. All recurrence data will be entered into the database automatically through participant surveys. Demographic and baseline data will be entered manually by the participant at study entry. If the data are not able to be entered by the participant (eg, loss of connection to the database at the study site), hard copies will be taken and the data manually entered by the researcher at the research office. In order to maintain the integrity of the data if this occurs, the data entry will be checked by a second researcher. Actigraph data will be processed in Actilife V.6.7.3 to transform the data into valid measurements of time spent (in minutes) in sedentary, light, moderate and vigorous activity as well as total activity level.

Ethics and dissemination

The trial has been prospectively registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ref: 12615000939594). We will also obtain ethics approval from the Australian Defence Force HREC.

The results of this study will be submitted for publication in a prominent journal with all actively collaborating investigators acknowledged. The George Institute Public Affairs and Marketing staff will ensure that both the conduct and the results of this study are widely and reliably publicised in the general media, including newspapers, radio talk-back programmes and TV news items.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Matthew Stevens at @_MattStevens_

Contributors: JL and CGM conceived the trial. MLS, C-WCL, MJH, JL, RB and CGM were responsible for the overall design. MLS, MJH, MG and TW-R developed the intervention. C-WCL and MvT designed the economic analysis. MLS and CN devised the integration with Defence. All authors contributed to writing the protocol and approved the manuscript.

Funding: TOPS Workers is funded by a WorkCover NSW Research Grant. TOPS Defence is partially funded by a Defence Health Foundation Grant. TOPS Primary Care is seeking funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia.

Competing interests: TW-R runs a business providing exercise classes for the prevention and management of low back pain.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (ref: 2015/728) and will be conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M et al. . Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P et al. . Measuring the global burden of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:155–65. 10.1016/j.berh.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD. Low back pain in Australian adults. Health provider utilization and care seeking. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004;27:327–35. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD. Low back pain in Australian adults: the economic burden. Asia Pacific J Public Heal 2003;15:79–87. 10.1177/101053950301500202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J et al. . Can rate of recovery be predicted in patients with acute low back pain? Development of a clinical prediction rule. Eur J Pain 2009;13:51–5. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menezes Costa LC, Maher CG, Mcauley JH et al. . Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b3829 10.1136/bmj.b3829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da C Menezes Costa L, Maher CG, Hancock MJ et al. . The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012;184: E613––24.. 10.1503/cmaj.120627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay EM, Dunn KM. Prognosis of low back pain in primary care. Studies over extended time scales are needed. BMJ 2009;339:816–17. 10.1136/bmj.b4014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster NE. Barriers and progress in the treatment of low back pain. BMC Med 2011;9:108 10.1186/1741-7015-9-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pengel LHM, Herbert RD, Maher CG et al. . Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ 2003;327:323–7. 10.1136/bmj.327.7410.323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marras WS, Ferguson SA, Burr D et al. . Low back pain recurrence in occupational environments. Spine 2007;32:2387–97. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181557be9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanton TR, Henschke N, Maher CG et al. . After an episode of acute low back pain, recurrence is unpredictable and not as common as previously thought. Spine 2008;33:2923–8. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818a3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steffens D, Maher CG, Pereira LSM et al. . Prevention of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:199–208. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M et al. . Standardised method for reporting exercise programmes: protocol for a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006682 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BUPA. Managing Back Pain. Get Back on Track 2014. http://www.bupa.com.au/staticfiles/BupaP3/Health and Wellness/MediaFiles/PDFs/9621-10-11S - Managing Back Pain 26pp (WEB READY).pdf

- 18.Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR et al. . American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–59. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuckey MI, Knight E, Petrella RJ. The step test and exercise prescription tool in primary care: a critical review. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med 2012;24:109–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito T, Shirado O, Suzuki H et al. . Lumbar trunk muscle endurance testing: an inexpensive alternative to a machine for evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77: 75–9. 10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90224-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreland J, Finch E, Stratford P et al. . Interrater reliability of six tests of trunk muscle function and endurance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1997;26:200–8. 10.2519/jospt.1997.26.4.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clapis PA, Davis SM, Davis RO. Reliability of inclinometer and goniometric measurements of hip extension flexibility using the modified Thomas test. Physiother Theory Pract 2008;24:135–41. 10.1080/09593980701378256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maher CG, Latimer J, Refshauge KM. Atlas of clinical tests and measures for low back pain. Melbourne: Manipulative Therapists Association of Australia, 2000.

- 24.Gajdosik R, Lusin G. Hamstring muscle tightness. Reliability of an active-knee-extension test. Phys Ther 1983;63:1085–90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6867117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandler J, McMillan J, Kibler B et al. . Safety of the squat exercise. ACSM Curr Comment. Published Online First: 2015. https://www.acsm.org/docs/current-comments/safetysquat.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plasqui G, Westerterp KR. Physical activity assessment with accelerometers: an evaluation against doubly labeled water. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2371–9. 10.1038/oby.2007.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Symonds TL, Burton AK, Tillotson KM et al. . Do attitudes and beliefs influence work loss due to low back trouble? Occup Med (Lond) 1996;46:25–32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8672790http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8672790 10.1093/occmed/46.1.25http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/46.1.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2000;31:73–86. 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J et al. . Assessment of diclofenac or spinal manipulative therapy, or both, in addition to recommended first-line treatment for acute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007:370;1638–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61686-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM et al. . Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a171 10.1136/bmj.a171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A et al. . The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med 2003;45:156–74. 10.1097/01.jom.0000052967.43131.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakatos E. Sample sizes based on the log-rank statistic in complex clinical trials. Biometrics 1988;44:229–41. 10.2307/2531910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]