Abstract

Objective

It is generally accepted that the patients’ hospital experience can influence their overall satisfaction with the outcome of lower limb arthroplasty; however, little is known about the factors that shape the hospital experience. The aim of this study was to develop an understanding of what patients like and do not like about their hospital experience with a view to providing insight into where service improvements could have the potential to improve the patient experience and their satisfaction, and whether they would recommend the procedure.

Design

A mixed methods (quan-QUAL) approach.

Setting

Large regional teaching hospital.

Participants

216 patients who had completed a postoperative postal questionnaire at 12 months following total knee or total hip arthroplasty.

Outcome measures

Overall satisfaction with the outcome of surgery, whether to recommend the procedure to another and the rating of patient hospital experience. Free text comments on the best and worst aspects of their hospital stay were evaluated using qualitative thematic analysis.

Results

Overall, 77% of patients were satisfied with their surgery, 79% reported a good–excellent hospital experience and 85% would recommend the surgery to another. Qualitative analysis revealed clear themes relating to communication, pain relief and the process experience. Comments on positive aspects of the hospital experience were related to feeling well informed and consulted about their care. Comments on the worst aspects of care were related to being made to wait without explanation, moved to different wards and when they felt invisible to the healthcare staff caring for them.

Conclusions

Positive patient experiences were closely linked to effective patient–health professional interactions and logistics of the hospital processes. Within arthroplasty services, the patient experience of healthcare could be enhanced by further attention to concepts of patient-centred care. Practical examples of this include more focus on developing staff–patient communication and the avoidance of ‘boarding’ procedures.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides greater insight into what patients like and dislike about their hospital experience, which can be directly translated into practical strategies for clinical service improvements.

The sample is relatively large for a qualitative study with sufficient size to achieve data saturation.

The study evaluated patient free text responses to open-ended questions. The primary limitation is that there was no further communication with the patients who responded, thus no opportunity for participants to clarify their comments.

Introduction

In today's healthcare environment, resource utilisation is driven by patient outcomes. As such, outcome metrics play an increasingly important role in moderating and developing clinical practice.1 Choosing suitable measures that provide meaningful information for the wide range of stakeholders can however be difficult.2

The ‘Friends and Family’ test has recently been introduced across the National Health Service (NHS),3 with the intention of providing a standardised approach to collecting patient feedback on the care and treatment provided. The aim of collecting such data is to inform approaches to maximising improvements in care, as well as providing patients with information to support decision-making. A previous study using lower limb arthroplasty as a model identified that responses to the Friends and Family test are mediated by three factors: meeting preoperative expectations, adequate pain management and a pleasant hospital experience.4

Patient experience, together with clinical effectiveness and patient safety, is one of the so-called ‘Three Pillars of Quality’.5 Consequently, provision of a high-quality patient experience is now considered to be a key component of quality patient care.6 However, maintaining and improving the quality of hospital care has been proved to be a particular challenge.7 In 2013, only 27% of patients in England rated their hospital experience as ‘very good’.8 Therefore, in order to ensure that quality improvement initiatives are focused on the areas where they are most needed, patient feedback on their hospital experiences is required.

Previous studies of hospital experience have been limited by the lack of a standardised approach.9 A number of issues have been highlighted,10 11 which include confusion over the definition of the term ‘experience’ as well as the validity and reliability of the instruments that are designed to measure the patient experience. It is, therefore, difficult to generalise findings across settings and contexts, and there is a lack of literature that focusses on the orthopaedic in-patient experience. Elements of the hospital experience, such as patient satisfaction, are often elicited through the use of surveys,12 which, while having the advantages of being able to administer to large sample sizes, do not necessarily offer the opportunity for the patient to give their point of view. One example is the Friends and Family test, which has been used previously4 as part of a statistical modelling methodology to highlight factors that predict patient satisfaction following lower limb joint replacement. While useful in identifying factors that influence satisfaction with outcome, the results are difficult to contextualise in terms of making improvements to the patient's journey through arthroplasty services. Furthermore, surveys are less likely to identify negative experiences and have been criticised for their lack of discriminant ability.13 Therefore, identification of areas for service improvement is unlikely to be achieved through large-scale simplistic surveys such as the Friends and Family test.

Measuring patient-reported quality of care on its own is unlikely to change clinical practice. To improve care, there is a need for sustained and targeted interventions.14 15 Within lower limb arthroplasty services, hospital experience has previously been shown to be a significant predictor of satisfaction with the outcome of surgery and the likelihood of recommending surgery to a friend or family member.4 There has been no work, however, to determine which factors shape a patient’s satisfaction with their hospital experience. Therefore, developing an understanding of what patients like and do not like about their hospital experience may help provide insight into where service improvements could have the potential to improve the patient experience, their satisfaction and ultimately their Friends and Family test recommendation response.

The aim of this study was, therefore, to undertake a more in-depth exploration of the patient responses associated with the experience metric and specifically to identify issues that are associated with a positive or negative patient experience.

Methods

Study design and sample

We employed a mixed methods (quan-QUAL) approach utilising quantitative summary statistics and qualitative thematic evaluation of patient feedback post arthroplasty to investigate the factors that influence the patient's satisfaction with the outcome and their willingness to recommend the procedure to another.

A sample of patient survey responses was obtained from the research database of the elective orthopaedic unit of a large regional teaching hospital. The study centre is the only hospital receiving adult referrals for a predominantly urban population of around 850 000.16 The elective unit has 52 inpatient beds across 2 specialist orthopaedic wards with specialist nursing and allied health professional staff. Surgical procedures were carried out by multiple consultant orthopaedic surgeons and their supervised trainees. Data had been collected through informed consent for inclusion in the database for which regional ethical approval had been obtained (11/AL/0079). All data were collected independently from the clinical team by the arthroplasty outcomes research unit of the associated university.

Data capture

This study employed retrospective evaluation of prospectively collected data. Postoperative postal questionnaires were administered at 12 months following surgery. As part of the postoperative survey, patients were asked specific questions as to their satisfaction following joint replacement. Patients were asked to indicate their overall satisfaction with the outcome on a four-point scale (very satisfied, satisfied, uncertain and dissatisfied); whether they ‘would recommend this operation to someone else?’ on a five-point Likert scale (definitely yes, possibly yes, probably not, certainly not and unsure); and to rate their overall hospital experience as either ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, ‘poor’ or ‘unknown’. Patients were also invited to respond in free text as to the best and worst aspects of their care; these individual response data were used for qualitative analysis.

Data analysis

Initial data analysis was by quantitative methodology to measure satisfaction and willingness to recommend the procedure to another. Responses to the Likert scale satisfaction questions were dichotomised into positive or negative responses for analysis. As per the methodology for the NHS Friends and Family test, ‘not sure’ responses were considered as negative.(REFS) Data are presented as percentages and between-group comparisons analysed by Pearson's χ2 test. Significance was accepted at p=0.05.

Free text data were transcribed from the handwritten responses, using NVivo (V.10) software, to facilitate a staged approach to analysis. Free text data were analysed using an interpretive phenomenological approach where responses were coded and synthesised into conceptual themes. Through interpretation of the response to the questions of what was good and less good about their hospital experience, it was hoped to be able to identify how patients understand their hospital experience. The free text patient responses were read repeatedly (familiarisation) and preliminary themes identified. Data were then sorted and synthesised by theme, bringing similar concepts together (thematic charting). The patient's language was maintained as far as possible to maintain the intended context. To enhance the trustworthiness of the qualitative analysis, credibility of the thematic analysis was addressed through peer scrutiny at all stages of the analysis phase.

Results

The database contained 4300 patient feedback forms from those who underwent hip or knee replacement between 2010 and 2013. We extracted a random 5% sample of responses as a meaningfully representative—yet logistically manageable—sample for thematic analysis. The selected data comprised 216 patients: 126 following hip arthroplasty and 90 post knee arthroplasty (table 1).

Table 1.

Satisfaction data

| Total population | Hip arthroplasty | Knee arthroplasty | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 216 | 126 | 90 | |

| Satisfied with outcome | 76.8% | 81.7% | 70% | 0.044* |

| Would recommend | 85% | 93% | 77% | 0.001 |

| Excellent to good hospital experience | 79% | 83% | 72% | 0.049 |

*Pearson's χ2.

In the hip replacement cohort, the average age was 69.1 (SD 12.6) years and 56% were females. In the knee replacement cohort, the average age was 70.2 (SD 9.4) years and 57% were females. The length of hospital stay was a median of 5 days in both groups.

Overall, 76.8% of patients were satisfied with the results of lower limb arthroplasty. Significantly more patients were satisfied following hip arthroplasty than knee arthroplasty (χ2, p=0.04, table 1) and would be likely to recommend the procedure to another (χ2 10.1, p=0.001). It was found that 96.9% of satisfied patients would recommend the procedure to another, while 56.0% of unsatisfied patients also would recommend the procedure (χ2, p<0.001, table 2). A significantly smaller proportion of patients undergoing knee arthroplasty rated their hospital experience as excellent–good (χ2 3.8, p=0.049) compared to those undergoing hip arthroplasty.

Table 2.

χ2 Data table satisfaction and recommendation responses

| Recommend | Not recommend | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied | 161 | 5 | 166 |

| Unsatisfied | 27 | 23 | 50 |

| Total | 188 | 28 | 216 |

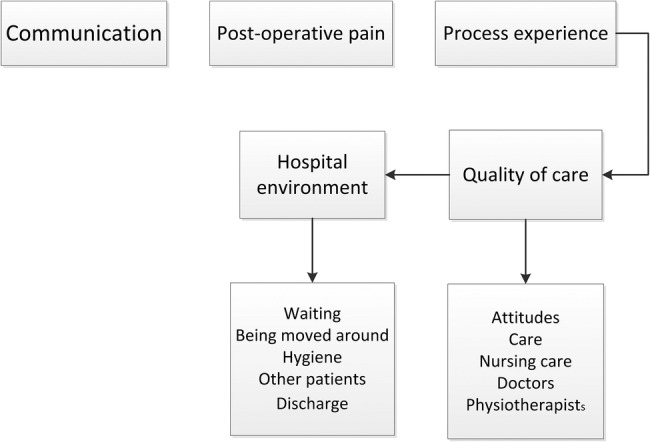

Qualitative analysis highlighted three interrelated codes (figure 1). Two of these codes, communication and pain, stood out as separate entities. The remaining responses could be grouped as ‘process experience’. This comprised two further subthemes: the quality of care received (staff attitudes, doctors, nursing care and physiotherapy) and the hospital environment (patient logistics, discharge processes and ward cleanliness). Analysis was conducted for the hip and knee responses separately. As the thematic responses were coded equally, we amalgamate these for reporting purposes.

Figure 1.

Major themes and subthemes identified. Hierarchy plot demonstrates the relationship between key findings. Communication, pain and the experience of the patient journey through arthroplasty services were three distinct themes. The process experience theme summarised two distinct but interrelated subthemes as the physical environment and logistical processes experienced during the hospital stay and the perception as to the quality of the care received.

The three major themes were highly reflected throughout the patient responses, and some interrelationship was also clearly evident. Specific patient feedback examples, reported verbatim, follow to illustrate the major findings.

Communication

Patients reported communication to be very important to their experience of joint replacement. This encompasses the entire process of care from initial preadmission letters to postoperative clinic visits. The major theme was that patients wanted to feel listened to; positive communication was likely to enhance satisfaction with the hospital experience and overall outcome even in cases where the patient also reported poor physical outcomes.

Two broad threads emerged from the communication code. The patient feeling well prepared for the process and that they received ongoing updates relevant to their care enhanced their experience.

Everything was explained fully and questions answered on the operation. I left the hospital with a higher regard for all the staff and administration of the hospital.

Conversely, when communication was lacking or did not prepare the patient for the eventual experience, the result was dissatisfaction with the episode of care.

None of the nurses or physiotherapists (on the ward) had been informed about my shoulder problem. I am still in pain with my shoulder, it is a great limitation

The doctors never once explained to me what was going on all they said was your getting there, god only knows where there term for there was….They spoke in doctors terms of which I never understood one bit

Pain

Experience of pain featured strongly in patients’ reports. Joint pain is the primary indication for arthroplasty surgery; thus, the patients are expected to have experienced high levels of chronic pain prior to surgery. The pain theme identified from the patient responses, however, reflects postoperative pain. Satisfaction seems related to the experience of postoperative pain in relation to preoperative expectations.

Having had both knees replaced I am a little disappointed in the final result! I was told I would be pain free! This is not the case.

Not having any pain after the op was the best thing about the surgery, which was not expected, which proves how the surgeons are fantastic in this very difficult operation also the anaesthetics, which I from time to time think how lucky I am to be able to walk & golf.

Process experience

As noted, this theme is a composite of two distinct, but related, subthemes.

Subtheme 1—the hospital environment

Each of the responses relating to being moved around made reference to the impact on the patient: feeling more vulnerable, loss of power and lack of communication, either between health staff or with patients and their families.

Being moved to a transplant ward from orthopaedics…strange unknown nurses etc—became disoriented—other patients not from orthopaedics—put back my progress.

Having been moved from one ward to another my consultant had trouble finding me on Monday morning and my notes were lost

The core insight remains similar to that from communication and waiting: that a little information could go a long way to resolving the effect of structural inequality on the patient.

Waiting was a frequent thread in the process experience theme. This focused around the day of surgery, and it was often referred to as the single worst aspect of the care received.

I had been told I was first on list then I was last (3.30pm). I had no fluid intake for 9 hours and the anaesthetist couldn't find a vein—this was worse than any pain in my hip

I had to sit in a small room for six hours not knowing if a bed would be available—extremely stressful—in fact when I arrived in the anaesthetic room two hours later the anaesthetist commented on how high my blood pressure was—I understand why this system is used but feel there is too much stress put on staff and patients…

The latter example highlights some expectation or insight on the part of the individual as to the necessities of waiting for a surgical slot, but this does not seem to influence their anxiety or stress during the waiting period. Clearly, in this example, the experience was memorable enough to stand out and be reported some 12 months following the procedure.

Subtheme 2—the quality of care

The most frequent comment across both sets of patients related to the quality of care received. Staff attitude encompasses all professions and staff grades. There was an even balance among the responses between positive and negative attitudes.

Everyone was so kind from the surgeons down to the cleaners

However, all staff—cleaners, those that served the food and the nursing staff were pleasant and approached the patients in a nice way

My treatment in admission was brusque in the extreme.

We were just numbers on a conveyor belt

These examples demonstrate the spread of positive comments across the medical and care professions. However, the negative elements appear to refer more commonly to nurses and nursing care. Patient comments as to nurse attitudes often referred to time constraints for care, and even positive experiences of nursing were often qualified with comments on the nurse being overworked:

The nursing staff are under so much pressure I feel sorry for them. This did not take away from the way I was looked after which I cannot fault in any way

Discussion

Overall, 77% of patients were satisfied with their surgery, 79% reported a good–excellent hospital experience and 85% would recommend the surgery to another. Though significantly more patients were satisfied following total hip arthroplasty (THA) than total knee arthroplasty (TKA), no differences were detected in the thematic responses between THA and TKA. Superior satisfaction outcomes for hip arthroplasty compared to knee arthroplasty are well described, and it is generally accepted that this is related to the increased physical demands and pain associated with knee arthroplasty.4 17 In this study, ‘clinical’ outcome comments were not a common feature of the responses—and not driving satisfaction/dissatisfaction responses. Instead, general factors related to the hospital stay, logistics and general patient experience were mostly associated with measures of patient satisfaction. Interestingly, while satisfied patients were likely to recommend the procedure to another, unsatisfied patients were equally likely to recommend or not recommend the procedure. This perhaps suggests that the factors that made the patients dissatisfied with the outcome of surgery may not be related to the actual surgical procedure—as half would still recommend arthroplasty to another despite being dissatisfied themselves.

Patient satisfaction has increasingly been the focus of outcome metrics in healthcare. Many studies have highlighted the influence of factors such as function and pain,18 and despite developments in implant design19 and surgical procedure,20 there has been relatively little improvement in satisfaction scores.21 22 One possible reason is a lack of standardised approach to addressing satisfaction and the general lack of consideration of the role of the hospital experience.

In this analysis, three key domains (pain management, communication and the hospital experience) were identified. No one domain was dominant, and it is likely they interrelate to some degree; however, they were identified through the qualitative process as distinct themes in the patient survey responses. These three domains were reflected in positive and negative comments and reflect previous statistical regression models which have shown that postoperative pain, meeting of preoperative expectations of outcome and the overall experience of the episode of care were the key factors in determining patient satisfaction with outcome—irrespective of clinical outcome.23

Pain and communication are clear constructs, while the process experience theme is more complex to interpret. This analysis demonstrates that the hospital environment and the quality of care are primary themes in expressing the patient experience, and their subsequent reports of satisfaction. Key issues within the theme of environment were patient movement between wards (the so-called process of ‘boarding’ patients to different wards), stress and anxiety caused by long waits on the day of surgery and ward environment. The unit in which this study was conducted is typical of arthroplasty provision in the NHS, where dedicated wards exist within large acute hospitals. These wards are staffed by specialist nurses and physiotherapists and typically support ‘early discharge schemes’, all of which have been previously associated with enhanced patient satisfaction.24 However, these wards also need to contribute to the overall hospital challenge of bed management and board patients in other departments to accommodate acute admissions. Ward moves have been shown to place patients, and especially the frail and elderly, at risk of falls and delirium, and present an infection control hazard.25 26 Such problems place patients at an increased risk of injury and mortality, leading to worse outcomes. The process of moving wards also has the potential to remove vulnerable patients from the supportive relationships that develop between patients and between patients and staff.

A common focus of the patients’ survey feedback was the quality of care they received, suggesting its relative importance in the process experience. In addition to its role in determining patient satisfaction, quality of care has been shown to be associated with patient-reported health-related quality of life at 1 year postsurgery.27 Nursing care was also frequently targeted for comment, with many patients feeling as though staff lacked the time to provide quality care. Studies28 have suggested that initiatives designed to increase the time that nursing staff spend in direct patient care result in improved patient safety although evidence in a specific orthopaedic setting is lacking.

The themes of communication and process experience are closely linked, and both reflect the value of the patient–health professional interaction in ensuring a positive hospital experience. Patients were satisfied when they felt well informed and consulted about their care. They were unsatisfied when they were made to wait without explanation, moved to different wards and when they felt invisible to the healthcare staff caring for them. This experience of the process of care clearly made a significant impact on many patients who were able to recall specific details of the days surrounding their surgery even at 1 year postsurgery. These findings reflect key elements of the concept of patient-centred care.29 A study of the patient-centred care model of acute in-patient care showed that emotional support, coordination of care and physical comfort had the strongest influence on outcomes.30 While not specific to the orthopaedic context, these findings lend support to our results, which reinforce the value of involving the patient in the process of care.

The Friends and Family test was introduced with the aim of providing a mechanism by which patients’ feedback could be used for continuous improvement and reinforcement of standards of care.3 The current study reinforces previous findings4 which identified the important role that satisfaction with the hospital experience plays in overall satisfaction and the likelihood of recommending the procedure to another. The results provide further context to the theme of hospital experience, highlighting how the delivery of healthcare can influence the patient perception of the episode of care, beyond the clinical outcomes, and have identified areas for modifying the process of care with a view to enhancing the patient experience of healthcare.

Strengths and limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that there was no further communication with the patients who responded; thus, there was no opportunity for participants to check their understanding or clarify meaning; and indeed it has only the participants’ perspective of events. Triangulation and/or member checking can also increase the confirmability and credibility of the data;31 however, opportunities for triangulation with other sources were limited in this instance. The key issue for the credibility of qualitative data, however, is its trustworthiness. One advantage of the use of postal questionnaires with open-ended questions is that larger samples can be collected while still providing the opportunity for the patient to offer their unique perspective. Completing the feedback at home encourages honesty in reporting. The sample size is relatively large for a qualitative study with an age and gender balance consistent for the UK lower limb arthroplasty population. The satisfaction scores reported in this sample, however, are slightly lower than those previously reported.4 This suggests a possible selection bias in the sample, despite random selection. There were no differences, however, arising in the themes arising from the free text comments between those who were satisfied and those who were not.

Patient feedback was collated 1 year following the index procedure; thus, it is possible that recall bias influences the patient's memory of the hospital experience; however, this affected all patients equally, and is unlikely to unbalance the findings. That we evaluated data from a single postoperative time point results that we cannot comment as to whether patient's responses are consistent or change with time following surgery. A further limitation of this study is that the data we have are not linked at an individual level to the patient's demographics. As such we cannot stratify the data by factors that could potentially influence outcomes such as surgical complications (DVT/PE, dislocations and infections) or patient factors such as the number of comorbid conditions. However, our unit's rates for the major arthroplasty complications (DVT, infection and dislocation) are ∼1% (in line with wider Scottish data); thus, it is unlikely this exerts a troublingly large influence on our findings. Furthermore, specific studies are required to evaluate the influence of individual predictors (such as comorbidity) on the themes we highlight as being related to patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

This study provides context as to the factors that influence the patients’ satisfaction following lower limb joint arthroplasty and their likelihood to recommend the process to another. Pain relief, communication and the logistical processes of the hospital stay were the primary themes that emerged. The results suggest that within arthroplasty services, the patient experience of healthcare could be enhanced by further attention to concepts of patient-centred care. Practical examples of this include more focus on developing staff–patient communication and the avoidance of ‘boarding’ procedures.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Judith Lane at @JudithLaneQMU

Contributors: JVL, DFH, DJM and CRH devised the study. DJM collected the data and contributed to the interpretation of the results. JVL and CE undertook the qualitative analysis. JVL and DFH undertook the quantitative analysis and wrote the first draft. CRH and CE contributed to the manuscript revision.

Funding: The database from which the data were accessed is supported by an unrestricted educational grant to the University of Edinburgh by Stryker.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: South East Scotland Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Brinker MR, O'Connor DP. Stakeholders in outcome measures: review from a clinical perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:3426–36. 10.1007/s11999-013-3265-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Connor DP, Brinker MR. Challenges in outcome measurement: clinical research perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:3496–503. 10.1007/s11999-013-3194-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS England. The Friends and Family Test 2014. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fft-imp-guid-14.pdf (accessed 3 Mar 2015).

- 4.Hamilton DF, Lane JV, Gaston P et al. Assessing treatment outcomes using a single question: the net promoter score. Bone Joint J 2014;96-B:622–8. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B5.32434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siriwardena A, Gillam S. Patient perspectives on quality. Qual Prim Care 2014;22:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quality I: Productivity and prevention (QIPP). The NHS atlas of variation in healthcare: reducing unwarranted variation to increase value and improve quality. UK: Right Care, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Care Quality Commission. Inpatient Survey 2013: National Summary. 2013. http://www.cqc.org.uk/public/reports-surveys-and-reviews/surveys/inpatient-survey-2013 (accessed 11 Feb 2015).

- 9.Jones EL, Wainwright TW, Foster JD et al. A systematic review of patient reported outcomes and patient experience in enhanced recovery after orthopaedic surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:89–94. 10.1308/003588414X13824511649571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beattie M, Lauder W, Atherton I et al. Instruments to measure patient experience of health care quality in hospitals: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2014;3:4 10.1186/2046-4053-3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards KJ, Duff J, Walker K. What really matters? A multi-view perspective of one patients hospital experience. Contemp Nurse 2014;28:5130–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham B, Green A, James M et al. Measuring patient satisfaction in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:80–4. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsianakas V, Maben J, Wiseman T et al. Using patients’ experiences to identify priorities for quality improvement in breast cancer care: patient narratives, surveys or both? BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:271 10.1186/1472-6963-12-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient 2014;7:235–41. 10.1007/s40271-014-0060-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coulter A, Locock L, Ziebland S et al. Collecting data on patient experience is not enough: they must be used to improve care. BMJ 2014;348:g2225 10.1136/bmj.g2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Register Office for Scotland. http://www.gro-scotland.gov.uk/statistics/theme/population/projections/sub-national/2010-based/tables.html (accessed 16 Sep 2014).

- 17.Hamilton DF, Henderson GR, Gaston P et al. Comparative outcomes of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. Postgrad Med J 2012;88:627–31. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs C, Christensen C. Factors influencing patient satisfaction two to five years after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29(6):1189–91. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton DF, Burnett R, Patton JT et al. Implant design influences patient outcomes following total knee arthroplasty: a prospective double blind randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2015;97:64–70. 10.1302/0301-620X.97B1.34254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindgren JV, Wretenberg P, Kärrholm J et al. Patient-reported outcome is influenced by surgical approach in total hip replacement: a study of the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register including 42,233 patients. Bone Joint J 2014;96-B:590–6. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B5.32341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maratt J, Lee Y, Lyman S et al. Predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1142–5. 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nam D, Nunley RM, Barrack RL. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a growing concern? Bone Joint J 2014;96-B(11 Supple A):96–100. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.34152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton DF, Lane JV, MacDonald D et al. What determines patient satisfaction with surgery? A prospective cohort study of 4709 patients following total joint replacement. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002525 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Specht K, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Kehlet H et al. High patient satisfaction in 445 patients who underwent fast-track hip or knee replacement. Acta Orthop 2015;86:702–7. 10.3109/17453674.2015.1063910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M et al. Environmental risk factors for delirium in hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1327–34. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurdo ME, Witham MD. Unnecessary ward moves—bad for patients; bad for healthcare systems. Age Ageing 2013;42:555–6. 10.1093/ageing/aft079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumann C, Rat AC, Mainard D et al. Importance of patient satisfaction with care in predicting osteoarthritis-specific health-related quality of life one year after total joint arthroplasty. Qual Life Res 2011;20:1581–8. 10.1007/s11136-011-9913-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright S, McSherry W. A systematic literature review of releasing time to care: the productive ward. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:1361–71. 10.1111/jocn.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Picker Institute. Principles of Patient Centred Care 2015. http://www.pickereurope.org/about-us/principles-of-patient-centred-care/ (accessed 24 Apr 2015).

- 30.Rathert C, Williams E, McCaughey D et al. Patient perceptions of patient-centred care: empirical test of a theoretical model. Health Expect 2015;18:199–209. 10.1111/hex.12020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ Info 2004;22:63–75. http://www.angelfire.com/theforce/shu_cohort_viii/images/Trustworthypaper.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]