Abstract

Introduction

Active transport to school (ATS) is a convenient way to increase physical activity and undertake an environmentally sustainable travel practice. The Built Environment and Active Transport to School (BEATS) Study examines ATS in adolescents in Dunedin, New Zealand, using ecological models for active transport that account for individual, social, environmental and policy factors. The study objectives are to: (1) understand the reasons behind adolescents and their parents' choice of transport mode to school; (2) examine the interaction between the transport choices, built environment, physical activity and weight status in adolescents; and (3) identify policies that promote or hinder ATS in adolescents.

Methods and analysis

The study will use a mixed-method approach incorporating both quantitative (surveys, anthropometry, accelerometers, Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis, mapping) and qualitative methods (focus groups, interviews) to gather data from students, parents, teachers and school principals. The core data will include accelerometer-measured physical activity, anthropometry, GIS measures of the built environment and the use of maps indicating route to school (students)/work (parents) and perceived safe/unsafe areas along the route. To provide comprehensive data for understanding how to change the infrastructure to support ATS, the study will also examine complementary variables such as individual, family and social factors, including student and parental perceptions of walking and cycling to school, parental perceptions of different modes of transport to school, perceptions of the neighbourhood environment, route to school (students)/work (parents), perceptions of driving, use of information communication technology, reasons for choosing a particular school and student and parental physical activity habits, screen time and weight status. The study has achieved a 100% school recruitment rate (12 secondary schools).

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the University of Otago Ethics Committee. The results will be actively disseminated through reports and presentations to stakeholders, symposiums and scientific publications.

Keywords: Active transport, Physical activity, Adolescents, Built environment, Social ecology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study strengths include a large representative sample of adolescents and parents across one city with a heterogeneous physical environment, data collection across the three seasons (fall, winter and spring) and objectively measured physical activity and built environment.

This study has achieved a 100% school recruitment rate.

Study limitations include cross-sectional study design, self-reported travel data, data collection in one city and lack of information on transport from school.

Introduction

Physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles among adolescents are global public health problems. If feasible, active transport to school (ATS) is a convenient way to integrate physical activity (PA) into everyday life and maintain or increase PA levels.1 2 ATS may lead to healthy, environmentally sustainable and economical travel practices over a lifetime. Despite great variations in the prevalence of ATS between countries,3 the rates of ATS among adolescents have consistently declined over the past decade in developed countries.4–8

Recent reviews identified a range of predictors of ATS in children and adolescents including demographic characteristics, individual and family factors, school factors, and social and physical environmental factors.9–12 Physical environment factors such as distance, presence of walking paths and/or bike lanes, availability of recreational facilities, urban form and road safety have a significant impact on encouraging or hindering active transport in youth.10 11 In contrast, land use mix, residential density and intersection density have not been consistently associated with ATS in children and adolescents.12 Understanding how these factors interact and influence transport choices among adolescents in a local context will enable the scientific community, policymakers, city planners and health promoters to address ATS barriers and reduce the reliance on motorised transport in this age group.

Most of the previous ATS studies in adolescents were conducted in urban areas of the USA,13 14 Canada,15 Australia16 and Western Europe.17 18 Though some commonalities may exist across high-income countries, reviews of the literature suggest that how the environment impacts physical activity and sedentary behaviour is not universal. The USA, Canada, Australia and Western Europe have different urban layouts and social norms compared to New Zealand. For instance, data from 12 countries showed between-country variation in residential density, intersection density, walkability index and park density.19 Limited data from New Zealand suggest that age, distance to school, number of vehicles and screens at home, coeducational status of the school and opportunity to socialise with friends influence the ATS of adolescents.20 Though some factors such as distance to school and parental safety concerns will be similar across countries, climate/weather and perceptions and features of the built environment are location-specific. In addition, social norms and policies can influence factors such as availability and use of public transportation, parental perceptions of safety, safety conscious parental practices, school zoning and reasons for choosing a particular school. In particular, New Zealand has one of the highest rates of private vehicle ownership per capita in the world.21 Finally, the climate/weather at the south end of the South Island of New Zealand is very different from parts of the North Island of New Zealand and Australia. Thus, the interaction between climate/weather and the environment may have a different impact on the ATS of adolescents. Therefore, understanding of the local context through an ecological approach examining multiple intersecting levels of influence is essential for identifying effective intervention strategies to promote ATS.

The Built Environment and Active Transport to School (BEATS) Study will examine ATS among adolescents on the South Island of New Zealand using ecological models for active transport10 22 which account for individual, social, environmental and policy factors. The study objectives are to: (1) understand the reasons behind adolescents and their parents' choice of transport mode to school; (2) examine the interaction between the transport choices, built environment, PA and weight status in adolescents; and (3) identify policies that promote or limit ATS in adolescents.

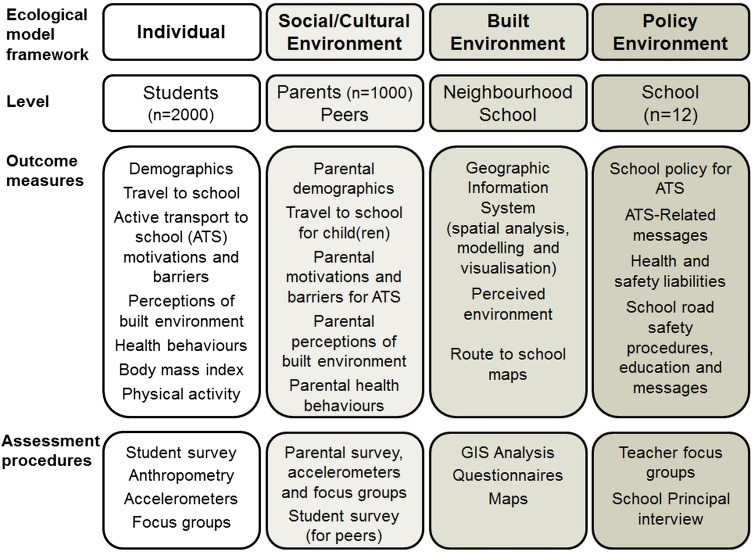

Study overview: This observational cross-sectional study will use a mixed-method approach incorporating both quantitative (surveys, anthropometry, accelerometers, Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis, mapping) and qualitative methods (focus groups and interviews) to gather data from students, parents, teachers and school principals (figure 1). The core data will include objective measures of PA (measured using accelerometers), anthropometry and the built environment (derived through GIS analytical techniques), and the use of maps to collect data about route to school (students)/work (parents) and perceived safe or unsafe areas along the route. To provide comprehensive data for understanding how to change the infrastructure to support ATS, the BEATS Study will also examine complementary variables such as individual, social and policy factors, including student and parental perceptions of walking and cycling to school, parental perceptions of different modes of transport to school, route to school (students)/work (parents), reasons for choosing a particular school and student and parental weight status, PA habits, sedentary behaviours and dietary habits (students only).

Figure 1.

The BEATS Study: conceptual framework, outcome measures and assessment procedures. (ATS=active transport to school; BEATS, Built Environment and Active Transport to School Study; GIS=Geographic Information System analysis).

Methods and analysis

Study Design: The BEATS Study is based on multisector collaborations between secondary schools, the city council, the local communities and academia.23 The study will be conducted in Dunedin, New Zealand (population ∼120 000). The BEATS Research Team is multidisciplinary with expertise ranging from exercise science, behavioural medicine and health promotion to geographic information science, statistics, consumer behaviour and environmental sociology. Details on the development of research and community collaborations, planning and study implementation have been described elsewhere.23

The study will consist of six subprojects that examine different components of the ecological models for active transport using quantitative (student survey and parental survey) and qualitative approaches (focus groups with students, parents and teachers; school principal interviews) (figure 1). Each substudy is described in more detail below. Data collection started in 2014 and will continue until 2017.

Quantitative data

BEATS student survey

Purpose: The BEATS Student Survey examines adolescents' transport to school habits, motivations and barriers for ATS, reasons for choosing a particular school, perceptions of the neighbourhood environment, health behaviours, weight status, perceptions of driving and the use of information communication technology. Specific aims are to: (1) examine the interaction between the transport choices, perceived (questionnaire) and objective measures (GIS analysis) of the built environment, PA and weight status in adolescents; (2) investigate the relationship of the adolescents' transport mode choice to the wider sociocultural, built environment and policy influences; and (3) compare motivations and barriers for walking versus cycling to school.

Participants: The BEATS Student Survey will recruit 2000 students in school years 9–13 (age: 13–18 years) attending 1 of 12 secondary schools in Dunedin. Cluster sampling will be undertaken using schools as sample units and classrooms within schools as clusters. In each school, two to four classes will be approached in years 9–13 (∼25 students per class x on average three classes per school year×5 school years×12 schools=≈4000 students). Owing to logistic reasons, the sampling of classes within the school will be left to the discretion of each school.

Using variance estimates calculated from data from the Otago School Students Lifestyle Surveys (2009 and 2011)20 in Dunedin schools (n=1458), 700 students per group would provide a statistical power of >0.90 at α=0.05 to detect a 10% difference in ATS use in boys versus girls, as well as differences in distance to school of 500 m and differences in built environment variables between ATS and motorised transport users. Allowing for 30% non-response, a total of 2000 students will be recruited. With an estimated recruitment rate of 50%, 4000 students will be invited to participate in the student survey.

Procedures: Students will be recruited through their school. Packages with study information and consent forms will be given to all invited students and their parents at the school 1–3 weeks prior to the scheduled date(s) for data collection. The study will be advertised in the school’s newsletter. Information about the study will also be sent by email from the school principal to the students and parents. Each school will be provided with prepaid envelopes containing relevant study information for those parents who do not have an email address. Parents will have an option to sign their consent either on paper or online. For adolescents under the age of 16 years, parental opt-in or parental opt-out consent will be used on the basis of the school's preference. Although students will also have an option to sign their consent online, each student will be required to sign a paper version of the consent.

Measures: Participants will complete an online survey (n=2000) and anthropometric measurements and will have an option to participate in PA assessment using accelerometers (n=250) and/or one focus group (n=50) (numbers indicate target sample sizes). Measures will include self-reported transport to school habits, perceptions of ATS, self-reported healthy lifestyle habits, anthropometry, school bag weight, accelerometer-measured PA, perceived and objectively measured built environment characteristics and the route to school drawn on a map.

Survey: Students will be surveyed once using a 30–40 min questionnaire developed specifically for this study. The questionnaire will be delivered and completed online, during classroom time, with 3–5 research assistants and a teacher present in the classroom. The questionnaire will include questions on demographics, reasons for choosing a particular school, transport to school habits, motivations and barriers to walking and cycling to school, perceived neighbourhood environment, health behaviours, perceptions of driving and use of information communication technology. All questions have been developed for use in school students, and most have been validated and used successfully in similar populations. Home address will be collected to facilitate calculation of distance to school (using GIS analysis) and determine neighbourhood deprivation score as a surrogate for students' socioeconomic status.24 Perceptions of neighbourhood environment will be examined using a validated Neighbourhood Environment Walkability Scale for Youth (NEWS-Y) (test–retest reliability in adolescents: ICC range 0.56 to 0.87).25 Health behaviours will be examined using questions from the Health Behaviour in School Children survey (permission obtained) (moderate-to-vigorous PA question: ICC 0.77; vigorous PA questions: ICC 0.71 for frequency and ICC 0.73 for duration; test–retest reliability for television viewing and computer use: Spearman correlations 0.55 to 0.68;26 Food Frequency Questionnaire for adolescents: Spearman correlations with the 7-day food diary −0.13 to 0.67).27

Anthropometry assessment: Height and weight will be measured at the time of the survey using standard procedures with participants in school uniforms (without shoes, jackets and sweaters). Height will be measured using a custom-made portable stadiometer and recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight will be measured using an electronic scale (A&D scale UC321, A&D Medical), recorded to the nearest 0.01 kg and reduced by 0.5 kg to account for clothing. Body mass index will be calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg·m−2). Weight status category will be determined using international age-specific and gender-specific cut-points.28 Waist circumference will be measured using a metal measurement tape in standing position at the narrowest part of the torso (above the umbilicus and below the xiphoid process). Students' school bags will be weighed as well. Anthropometry measurements will be taken in a private, screened off area of the classroom by trained researchers.

Accelerometer Assessment: One to three weeks after completing the online questionnaire, consenting adolescents will be instructed and shown at school how to attach and wear an accelerometer (ActiGraph, GT3XPlus, Pensacola, Florida, USA). Participants will wear an accelerometer above the right hip for at least 12 h per day for seven consecutive days. The valid wear time criteria for wearing an accelerometer will be set as at least 5 days, for a minimum of 10 h per day.29 30 To promote compliance, participants will be given a log to record the times and reasons for taking the accelerometer off during the day and will receive emails, phone calls or text reminders. After 7 days, participants will return their accelerometer at their school. Activity counts will be stored in 10 s and 30 s interval counts to detect short bursts of vigorous PA.31 Data with 10 s interval counts will be analysed using MeterPlus software using Evenson cut-points.32 Variables will include average moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary times (daily, weekday and weekend), 1 hour before school (8:00 to 9:00), 1 h after school (15:00 to 16:00), and late after-school hours (16:00 to 20:00).

Mapping a route to school: After completing the survey and anthropometry, students will be provided with an A3 size map of the city with their school and city centre highlighted. Students will be asked to draw their route to school, indicate their mode of transport (including multimodal transport), mark the areas along the route where they feel safe or unsafe and comment on safety issues along the route. These paper maps will be subsequently digitised through tracing the drawn route on a roads spatial data layer, using a GIS. This means that the recorded route will follow the surveyed road network and will not be subject to the geometric irregularities associated with hand-drawing. Transport mode and safety attributes will be attached to the traced route lines where they occur. Map-measured routes have been previously used as valid and were significantly different from GIS-based network measurements,33 which were also featured in this study.

Geographic Information System Analysis: A built environment GIS analysis will be conducted for the home and school neighbourhoods and route to school. Objective measures of the built environment (distance from home to school, land mix use, residential density, intersection density and topography) and route to school analysis (distance) will be derived through GIS analytical techniques using Esri ArcGIS V.10.2 Software. Distance from home to school will be calculated in two ways: (1) actual route from home to school marked on a map, as previously described and (2) using the shortest route on a topologically connected transport network, based on geocoded home and school addresses. For the latter, distances will be calculated using the following steps: (1) geocoding home addresses to get address coordinates; (2) extracting school address points from reference spatial data; (3) constructing an integrated and connected road and track network; (4) attaching the home and school point locations to this network; and (5) using R scripting to calculate the shortest travel distance on the network for each study participant for each route using the edges (roads, tracks) and nodes (home, school and road/track intersection points) forming the network. Such GIS-calculated distances were found to be statistically similar to distances measured from Global Positioning System (GPS) data collected on the home-to-school route.34

The intersection density will be calculated as a count of intersections along the route using the route and junction data derived from the connected transport network. A 100 m buffer zone based on the route will be used to obtain a count of the junctions on or near the route. The land use mix variable along the school routes will be calculated as the mean land use mix entropy35 using the Dunedin City Council reference data (value range between 0 (the land use mix along the route is of a single class) and 1 (the land use mix along the route is evenly distributed among all land use classes)). The topography of each route will be represented by the altitude difference and total altitude gain variables, calculated in conjunction with digital elevation data.

Analysis: Data analysis will include descriptive statistics, examination of the normal distribution of data (the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of the corresponding histogram) and the homogeneity of variance (Levene's test). Generalised linear mixed effects models will be used to investigate relationships at the individual, social and environmental levels and to take account of the cluster sampling scheme. Binary variables (eg, walking to school or not) will be modelled with logistic regression and ordinal variables (eg, frequency of walking to school on a semantic frequency scale) with proportional odds regression, accounting for the cluster sampling scheme. Analyses will be conducted with R and SPSS Statistical Package V.22.0.

BEATS parental survey

Purpose: The BEATS Parental Survey will examine parental perceptions of different transport modes to school, parental motivations and barriers for ATS, parental past travel to school habits, perceptions of the built environment and safety of the route to school, physical activity habits, health behaviours, weight status and route to work and their relationship to ATS habits in adolescents. Specific aims are: (1) to explore the parental social and cultural environment in relationship to ATS habits of their children; (2) to compare parental and adolescents' perceptions of the built environment, and especially safety for ATS and (3) to compare parental and adolescents' physical activity habits, and motivations for and barriers to ATS (in conjunction with the BEATS Student Survey).

Participants: Parent participants will be recruited through 12 secondary schools in Dunedin (1000 parents for the parental survey (80–100 parents per school); 250 parents for physical activity monitoring; and 30 parents for focus groups). We will approach parents of students in four classes in years 9–13 in each school (∼25 students per class×4 classes per school year×5 school years×12 schools=≈6000 parents). With an expected participation rate of 15–20% (an average parental participation rate in school-initiated surveys in Dunedin secondary schools), we will recruit 1000 parents to complete the survey (80–100 parents per school). In the case of lower participation rate, the participating schools will be asked to send the study information to all parents at their school (by email or post). The study will be advertised through social media such as Facebook, local community newspapers as well as poster advertising in workplaces, local community and sporting centres. Owing to complexity of the overall BEATS Study, the student and parental components will be planned as distinct research projects. Therefore, parents will be able to participate irrespective of their child's participation. This approach will be a limitation to the creation of parent–child dyads for the purpose of the analysis. Therefore, we will use child-level and parent-level data to make comparisons, when appropriate, and make inferences in the light of the limitations acknowledged above.

From the parents who consent to participate in the physical activity study, a subsample of 250 parents (equal gender representation) will be randomly selected and contacted to confirm their interest and willingness to wear an accelerometer for 7 days. Approximately 30 parents will be purposefully recruited for focus groups to provide a broad representation of participants based on a number of sociodemographic, attitudinal and behavioural characteristics relevant to the topic under consideration.

Procedures: Recruitment of parents for the BEATS Parental Survey will take place using the following procedures: (1) advertising in the school's newsletters; (2) giving the BEATS parental pamphlet to students at school to take home; and (3) two email/mail invitation messages sent from the school principal to the parents at their school. The BEATS parental pamphlet and email from the school principal to parents will include brief information about student and parental surveys, a sign-up sheet for parents, relevant links to the BEATS Study website for further information about the BEATS Parental Survey, downloading study information sheets and consent forms, and signing consent online.

Invited parents will be given 1 month to respond to the invitation to participate in the BEATS Parental Survey. Only one parent per household will be included in the data analysis. Multiple parents per household will be determined from a combination of home address data, child's school, child's school year and parent's gender. The second parent from the same household will be removed from the analysis. However, separated parents (from different households) will be included in the analysis.

Measures: Parent participants will complete an online survey and will also have an option to participate in physical activity assessment (using accelerometers) with anthropometric measurements and/or one focus group.

Questionnaire: Parents will be surveyed once using a questionnaire developed specifically for this study. Participants will have a choice of completing the survey online (Qualitrics software) or on a paper copy mailed to them. This approach will not disadvantage parents of families with a lower socioeconomic status or families with limited or no computer and internet access at home. The parents will complete the 25–30 min questionnaire in their own spare time. The questionnaire will include questions on demographics (including self-reported height and weight), transport to school habits of their children, perceptions of walking, cycling, driving and bussing to school, safety of child's route to school, perceived neighbourhood environment, PA habits, transport to work details and perceptions of driving. Parental barriers to walking and cycling to school will be examined using previously validated instruments (internal consistency 0.71–0.86; ICC 0.74–0.81)36 37 and will be supplemented with specific questions (eg, parental attitude towards cycle skills training and assessment of needs for a bike library or cycle skills training for adolescents). Perceptions of the neighbourhood environment will be examined using a validated parent version of the Neighbourhood Environment Walkability Scale for Youth (NEWS-Y) (test–retest reliability in parents of adolescents: ICC range 0.61 to 0.78).25 Parental self-reported PA habits will be assessed using questions from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (I-PAQ) Long Form (test–retest reliability with median ICC of ∼80)38 and brief measures of PA.39 40

Parental Physical Activity Assessment: Within 2 weeks of completing the questionnaire, consenting parents will attend a 20 min appointment to set up an accelerometer (ActiGraph, GT3XPlus, Pensacola, Florida, USA) and obtain anthropometry measurements (height, weight and waist circumference assessed using standard procedures described above). During the study appointment, participants will be instructed and shown how to attach and wear an accelerometer. The appointments will be set up at one of the designated locations throughout the city. To facilitate recruitment, participants will be able to choose a location and time that is most convenient for them. Anthropometry measurements will be taken in a private room by a trained researcher. Participants will wear an accelerometer above the right hip for at least 12 h per day for seven consecutive days. The valid wear time criteria for wearing an accelerometer will be set for at least 5 days, for a minimum of 10 h per day. To promote wearing an accelerometer, participants will be given a log to record the times and reasons for taking the accelerometers off during the day and will receive emails, phone calls or text reminders. After 7 days, participants will return their accelerometer or mail it using a prepaid envelope. Data will be analysed using MeterPlus software using the threshold criteria for adults.41

GIS analysis: Objective measures of the built environment (distance to workplace and child's school, land mix use, residential density, intersection density and topography) and route to work analysis (distance, route proximity to child's/children's school(s)) will be derived through GIS analytical techniques using Esri ArcGIS 10.2 Software and code written in R, using the same methods described above for the student study. Distances (home to child's school, home to parental workplace and child's school to parental workplace) will be calculated on the topologically connected transport network, based on geocoded work addresses, as well as home and children's school addresses. The intersection density will be calculated as described for the student study. The land use mix variable along the school routes was calculated as the mean land use mix entropy,35 using the Dunedin City Council reference data (as described above). The topography of each route will again be evaluated through the altitude difference and total altitude gain variables.

Sample size calculation: As described above, 6000 parents will be invited to participate in the BEATS Parental Survey. With expected participation rates of 15% to 20%, 1000 parents will be recruited. Assuming that the relationship between parental attitudes and child PA42 and between parental PA and child PA43 is small (r=0.15 to 0.25), a sample of 347 parent–child dyads will be sufficient to detect r≥0.15 with α=0.05 and β=0.80. Using the same α and β, 394 dyads will be sufficient to detect a small effect size using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Therefore, we will aim for at least 400 dyads in our sample. A sample size of 250 parents in the PA substudy will be sufficient to detect medium effect sizes for comparison between the groups using ANOVA.

Analysis: Data analysis will include descriptive statistics, examination of the normal distribution of data (the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of the corresponding histogram) and the homogeneity of variance (Levene's test)). Generalised linear mixed-effects models will be used to examine parental attitudes towards ATS, their perceptions of the built environment (especially safety for cycling to school) and objective measures of the built environment as correlates of ATS in adolescents. Data analysis will take into account the cluster sampling scheme. Bivariate correlations and ANOVA will be used to examine relationships and compare parental weight status and PA with parental attitudes towards ATS and adolescents' PA, weight status and transport to school habits and to compare parental and adolescents' motivations and barriers to ATS.

As described previously, 6000 parents will be invited to participate in the BEATS Parental Survey. With expected participation rates of 15–20%, ∼1000 parents will be enrolled in the study with at least 400 parent-child dyads and parents in the PA substudy.

Qualitative data

BEATS focus groups with students, parents and teachers

Purpose: Focus groups will be conducted with groups of students, parents and teachers to explore their perceptions of active transport, transport to school, transport modes, motivations and barriers to travel behaviour and modal choice, adolescents' internet use and use of information communication technologies (table 1). The focus groups will provide qualitative empirical data to complement the quantitative survey data, offering an opportunity to delve into the meanings, perceptions and interpretations of the participants.44

Table 1.

Themes for BEATS Study focus groups and interviews

| Focus groups/interview themes | |

|---|---|

| Student focus group |

|

| Parental focus group |

|

| Teachers' focus group |

|

| School principal interview |

|

Participants: Student participants will be recruited from the Student Survey sample. To account for discrete school contexts, all 12 participating schools will be offered the opportunity to participate in one focus group of 8–10 students with equal gender and age representation. Parent participants will be recruited through advertisements at schools, workplaces, local community and sporting centres. Six to eight parental focus groups will be conducted, with 4–10 participants per focus group and up to 30 participants recruited. Teacher participants will be recruited through participating schools. Four to six teachers' focus groups will be conducted with four to six teachers per session and up to 24 participants. Sample size for student, parental and teachers' focus groups will be determined by redundancy and saturation.45 46

Procedures: The focus group session will last up to 1 hour, and be conducted at a time suitable for each group of participants. For students and teachers, the focus group will take place in a quiet and private location at each school. For parental focus groups, a neutral and mutually convenient location will be used. Drinks and snack food will be provided for the participants to create a more relaxed environment and foster a positive environment in which the participants feel free to speak at ease and without judgement. Participants will be advised that they do not need to answer any of the questions should they not wish to do so. They will be reassured that their responses will be anonymised in any subsequent reporting of the empirical material. Participants will also be encouraged to keep the content of the focus group discussion between themselves. Sessions will end with an opportunity to ask questions and discuss ATS-related issues not covered by the focus group questions.

The focus groups will be facilitated by up to three researchers. The lead researcher (DH) will direct the session, ask the questions according to the semistructured interview question matrix (table 1) and develop dialogue between the focus group participants, ensuring that all participants' voices are being heard. Additional researchers will provide support and assistance to the lead researcher, and take notes on key issues arising through the session.

The lead researcher will be responsible for identifying and mitigating any risks which could affect the outcomes of the research. Potential risks include: (1) potential power dynamics within the student focus group session since all focus group participants will be known to one another as students from the same school and a mix of age groups; (2) domination over a conversation in parental focus group (to be minimised by allowing only one parent per family to participate in any one focus group); and (3) potential power dynamics in teachers’ focus group resulting from different roles at the school or personal relationships that could affect the ability of participants to speak openly.

Measures: Focus group themes for students, parents and teachers are listed in table 1.

Analysis: Focus group sessions will be digitally audio recorded, fully transcribed and analysed using NVivo10 qualitative analysis software. Detailed notes taken by researchers during and immediately after each focus group will allow the incorporation and development of lines of enquiry for subsequent focus groups. This is due to the highly dynamic and interactive nature of qualitative data generation and analysis.47–49 Thematic analysis will be used to search for emergent themes.50 This approach is popular in qualitative research, with the search for themes equating to the use of variables in quantitative research.51 Themes emerge as a result of both inductive and deductive reasoning, drawing together field-generated themes and the over-riding conceptual framework.51

After uploading the transcriptions to the NVivo10 software, a liberal coding approach will be used to explore the empirical material, to identify similarities, differences, patterns and structures in the text.52 53 Following this, an interpretivist approach to analysis will be used to get a greater depth of understanding. This reading of the material will consider the survey findings and draw parallels across the different research methods. One researcher (DH) will code the material. Coded material will be shared with other researchers and triangulated with the focus group session notes. Triangulation (eg, of researchers, methods, informants) can limit methodological and personal biases, thereby increasing the trustworthiness of the research findings.54 Trustworthiness is thought to be achieved through the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of the research.46 Trustworthiness is a qualitative standard similar to that of generalisability and objectivity in quantitative approaches.46

BEATS school principal interviews

Purpose: The school principal interviews will explore school principals' perceptions of ATS, school neighbourhood environment, school's policies for ATS, road safety procedures around the school and personal travel habits.

Participants: Principals of all 12 participating schools will be invited to participate. Either the school principal or deputy principal will be eligible to participate in this interview.

Procedures: A 60 min semistructured interview will be conducted at the school and attended by two researchers. The lead researcher will direct the interview and ask the questions according to the interview question matrix. The same researcher will lead all school principal interviews for consistency. The second researcher will provide assistance to the first researcher and take notes on the conversation arising through the session. Before the session, participants will provide written consent and be reassured that their responses (including identifiable comments about their particular school) will be anonymised in any subsequent reporting of the empirical material.

Measures: The school principal interviews will involve an open-ended questioning technique. The general line of questioning will include gaining information about school policy for ATS and school-specific concerns related to ATS (table 1). Since the interview will be semistructured in nature, there will be a loose line of questioning that will be developed prior to the interview (table 1), as well as flexibility to develop specific themes of interest to each school principal.

Analysis: The interview sessions will be digitally audio recorded, fully transcribed and analysed by NVivo10 qualitative analysis software. In line with Basit,53 analysis and interpretation will begin during the interview process, and continue through transcription, formal analysis and write-up, as ‘a dynamic, intuitive and creative process of inductive reasoning, thinking and theorizing’.53 Thus, the identification of themes from the empirical material will begin during the interview process. The formal analysis will take place using the same analytical process used for the focus group sessions.

Mixed-methods design

The approach to data integration will be one of convergent parallel or ‘concurrent triangulation’.55 The empirical material from the quantitative and qualitative strands of this research will be equal, and will be used to ‘more accurately define relationships among variables of interest’.56 Thus, neither quantitative nor qualitative data will be considered to be ‘truer’, or given more weight, than the other. Through this approach, findings are understood as evidence that can be either narrative or numeric, to examine the same phenomenon, namely Active Transport to School. Specifically, consistent with the notion of ‘parallel-datasets’ forwarded by Creswell and Plano Clark,57 both methods will be used to address complementary aspects of the same phenomenon, and integration of qualitative and quantitative data will take place in the interpretation/discussion phase. To this end, both sources of data will be analysed separately and convergences and divergences in the findings will subsequently be identified in the context of side-by-side comparison and reported, and interpretations will be provided.

Strengths and limitations

The BEATS Study will extend current national58 59 and international projects60 examining the association of the built and social environments and health in adolescents. The review by Adams et al19 shows that between-country variation exists in how the primary indicators of walkability related to active transport. The cross-sectional study described in this article is being conducted in a country with one of the highest per capita levels of car ownership in the world, with narrow roads and in a city with cool and wet weather. These are all factors that may influence the physical activity and transit decisions of parents and children. Thus, New Zealand and the city of Dunedin in particular, provide a unique context to examine the correlates of active transport.

The strengths of this study include a 100% school recruitment rate, a large representative sample of adolescents and parents across one city with a heterogeneous physical environment, comprehensive examination of personal, social, environmental and policy correlates of ATS, data collection across the three seasons (fall, winter and spring) and objectively measured physical activity and built environment. The large study sample will enable comparison of student and parental barriers and facilitators for ATS across neighbourhoods stratified by socioeconomic status and walkability, using both perceived and objective measures of the built environment. In addition, data from students and parental surveys will allow examination and comparison of correlates of walking and cycling to school from parental and adolescents' perspectives. Therefore, the BEATS Study will provide relevant and timely data to examine correlates of ATS at all levels of the ecological frameworks used in this study (figure 1). Study limitations include cross-sectional study design, self-reported travel data, data collection in one city and lack of information on transport from school.

Ethics and dissemination

All participants will sign their own consent. Parents will have an option to sign their consent either on paper or online. For adolescents under the age of 16 years, parental opt-in or parental opt-out consent will be used on the basis of the school's preference. Although students will also have an option to sign their consent online, each student will be required to sign a paper version of the consent. The results will be actively disseminated through reports and presentations to stakeholders, individual reports to each participating school, organisation of the symposiums for the local community, scientific conference presentations and research publications.23 In addition, the results will be disseminated through social media such as Facebook, profiled on our research laboratory website and the BEATS Study website, and presentations at health promotion forums.

The BEATS Study will provide comprehensive baseline data to evaluate school-based interventions in Dunedin (eg, Cycle Skills Training and Bike Library in South Dunedin). In the long run, data collected as a part of the study will form comprehensive baseline data for a natural experiment to examine changes in student and parental perceptions of the built environment and ATS as a result of on-road and off-road cycle infrastructure construction in several Dunedin neighbourhoods (2014–2017). Taken together, these findings will provide important information for designing future school-wide, neighbourhood-wide and city-wide interventions to encourage active transport among adolescents and use active transport as a means of increasing physical activity in this age group. The BEATS Study findings will be relevant to the local context and practices due to inclusion of decisionmakers and other knowledge users on the research team and a strong commitment to knowledge exchange and mobilisation. The comprehensiveness of the study will contribute to the advancement of scientific knowledge and understanding of factors that influence ATS in adolescents.

In summary, the BEATS Study will provide timely and highly relevant information to understand individual, social, environmental and policy factors that influence ATS within the New Zealand context. The results will provide valuable information for the schools, city councils, transport agencies and land planners and help inform future changes to the built environment, school policy development and city policy development. The results will also inform health promotion efforts and shape future interventions to promote ATS in New Zealand adolescents and advance further the scientific knowledge in this field.

Acknowledgments

The BEATS Study is a collaboration between the Dunedin Secondary Schools' Partnership, Dunedin City Council and University of Otago. The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the BEATS Study Advisory Board (Mr Andrew Lonie, Mrs Ruth Zeinert, Dr Tara Duncan, Dr Susan Sandretto, Dr Janet Stephenson), research personnel (study coordinators Ashley Mountfort, Emily Brook and Leiana Sloane, research assistants, research students and volunteers) and all participating schools, students, parents, teachers and school principals.

Footnotes

Contributors: SM is the principal investigator who conceptualised the overall study, established research collaborations and led the project implementation. All authors contributed to the design of the study and questionnaires. SM, JW, AM, EGB and JCS obtained research funding. JW was responsible for statistical analysis. DH led the qualitative research design, data collection and analysis. AM was responsible for Geographic Information Systems data analysis. GW assisted with the recruitment of schools. SM drafted this manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand Emerging Researcher First Grant (14/565), National Heart Foundation of New Zealand (1602 and 1615), Lottery Health Research Grant (Applic 341129), University of Otago Research Grant (UORG 2014) and Dunedin City Council. The funding bodies did not have a role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, data interpretation or writing of this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Otago Ethics Committee (reference number 13/203; 19 July 2013).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Faulkner GEJ, Buliung RN, Flora PK et al. Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: a systematic review. Prev Med 2009;48:3–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendoza JA, Watson K, Nguyen N et al. Active commuting to school and association with physical activity and adiposity among US youth. J Phys Act Health 2011;8:488–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthold R, Cowan MJ, Autenrieth CS et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior among school children: a 34-country comparison. J Pediatr 2010;157:43–9 e41 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald NC. Active transportation to school: trends among U.S. schoolchildren, 1969–2001. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:509–16. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Transport: New Zealand Household Travel Survey 2007–2010 Wellington: Ministry of Transport, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chillón P, Martínez-Gómez D, Ortega FB et al. The AVENA and AFINOS Studies. Six-year trend in active commuting to school in Spanish adolescents. Int J Behav Med 2013;20:529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray CE, Larouche R, Barnes JD et al. Are we driving our kids to unhealthy habits? Results of the Active Healthy Kids Canada 2013 report card on physical activity for children and youth. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:6009–20. 10.3390/ijerph110606009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Transport. 25 years of New Zealand travel: New Zealand household travel 1989–2014. Wellington: Ministry of Transport, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davison KK, Werder JL, Lawson CT. Children's active commuting to school: current knowledge and future directions. Prev Chron Dis 2008;5:A100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panter JR, Jones AP, van Sluijs EM. Environmental determinants of active travel in youth: a review and framework for future research. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:34 10.1186/1479-5868-5-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pont K, Ziviani J, Wadley D et al. Environmental correlates of children's active transportation: a systematic literature review. Health Place 2009;15:827–40. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong BY, Faulkner G, Buliung R. GIS measured environmental correlates of active school transport: a systematic review of 14 studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:39 10.1186/1479-5868-8-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr J, Rosenberg D, Sallis JF et al. Active commuting to school: associations with environment and parental concerns. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:787–94. 10.1249/01.mss.0000210208.63565.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babey SH, Hastert TA, Huang W et al. Sociodemographic, family, and environmental factors associated with active commuting to school among US adolescents. J Public Health Policy 2009;30(Suppl 1):S203–220. 10.1057/jphp.2008.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen K, Gilliland J, Hess P et al. The influence of the physical environment and sociodemographic characteristics on children's mode of travel to and from school. Am J Public Health 2009;99:520–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timperio A, Ball K, Salmon J et al. Personal, family, social, and environmental correlates of active commuting to school. Am J Prev Med 2006;30:45–51. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panter JR, Jones AP, Van Sluijs EM et al. Neighborhood, route, and school environments and children's active commuting. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:268–78. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bringolf-Isler B, Grize L, Mader U et al. Personal and environmental factors associated with active commuting to school in Switzerland. Prev Med 2008;46:67–73. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams MA, Frank LD, Schipperijn J et al. International variation in neighborhood walkability, transit, and recreation environments using geographic information systems: the IPEN adult study. Int J Health Geogr 2014;13:43 10.1186/1476-072X-13-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandic S, Leon de la Barra S, Garcia Bengoechea E et al. Personal, social and environmental correlates of active transport to school among adolescents in Otago, New Zealand. J Sci Med Sport 2015;18:432–7. 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motor vehicles (per 1,000 people). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.VEH.NVEH.P3.

- 22.Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W et al. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:297–322. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandic S, Mountfort A, Hopkins D et al. Built Environment and Active Transport to School (BEATS) Study: multidisciplinary and multi-sector collaboration for physical activity promotion. RETOS 2015;28:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salmond C, Crampton P, King P et al. NZiDep: a New Zealand index of socioeconomic deprivation for individuals. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1474–85. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg D, Ding D, Sallis JF et al. Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale for Youth (NEWS-Y): reliability and relationship with physical activity. Prev Med 2009;49:213–18. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitz KH, Harnack L, Fulton JE et al. Reliability and validity of a brief questionnaire to assess television viewing and computer use by middle school children. J Sch Health 2004;74:370–7. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06632.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Currie C, Nic Gabhainn S, Godeau E et al. The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children: WHO Collaborative Cross-National (HBSC) study: origins, concept, history and development 1982–2008. Int J Public Health 2009;54(Suppl 2):131–9. 10.1007/s00038-009-5404-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3. 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherar LB, Griew P, Esliger DW et al. International children's accelerometry database (ICAD): design and methods. BMC Public Health 2011;11:485 10.1186/1471-2458-11-485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trost SG. Measurement of physical activity in children and adolescents. Am J Lifestyle Med 2007;1:299–314. 10.1177/1559827607301686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(11 Suppl):S531–543. 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K et al. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sport Sci 2008;26:1557–65. 10.1080/02640410802334196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stigell E, Schantz P. Methods for determining route distances in active commuting—their validity and reproducability. J Transp Geogr 2011;19:12 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan MJ, Mummery WK. GIS or GPS? A comparison of two methods for assessing route taken during active transport. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:51–3. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cervero R. Travel demand and the 3Ds: density, diversity, and design. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 1997;2:199. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman H, Kerr J, Norman GJ et al. Reliability and validity of destination-specific barriers to walking and cycling for youth. Prev Med 2008;46:311–16. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ducheyne F, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Spittaels H et al. Individual, social and physical environmental correlates of ‘never’ and ‘always’ cycling to school among 10 to 12-year-old children living within a 3.0 km distance from school. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:142 10.1186/1479-5868-9-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson G, Westerterp KR. Assessment of the physical activity level with two questions: validation with doubly labeled water. Int J Obes 2008;32:1031–3. 10.1038/ijo.2008.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milton K, Clemes S, Bull F. Can a single question provide an accurate measure of physical activity? Br J Sports Med 2013;47:44–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridgers ND, Fairclogh S. Assessing free-living physical activity using accelerometry: practical issues for researchers and practitioners. Eur J Sport Sci 2011;11:205–13. 10.1080/17461391.2010.501116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhodes RE, Berry T, Craig CL et al. Understanding parental support of child physical activity behavior. Am J Health Behav 2013;37:469–77. 10.5993/AJHB.37.4.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stearns JA, Cutumisu N, Ball G et al. Neighbourhood walkability and pedometer-determined physical activity of 6 to 10-year old children [abstract]. Ghent, Belgium: ISBNPA, 2013:201–2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbour R, Kitzinger J. Developing focus group research: politics, theory and practice. London, UK: SAGE, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev 1989;14:532–50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, California: SAGE Publications, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mason J. Qualitative researching. London: Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lofland J, Lofland LH. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitiative observation and analysis. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman D, Marvasti A. Doing qualitative research: a comprehensive guide. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. London: Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veal AJ. Research methods for leisure and tourism: a practical guide. London: Financial Times Management, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seidel J, Kelle U. Different functions of coding in the analysis of textual data. In: Kelle U, Prein G, Bird K, eds. Computer-aided qualitative data analysis: theory, methods and practice. London: SAGE Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basit T. Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educ Res 2003;45:143–54. 10.1080/0013188032000133548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Decrop A. Trustworthiness in qualitative tourism research. In: Goodson JPL, ed. Qualitative research in tourism: ontologies, epistemologies and methodologies. Abingdon: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML et al. Advances in mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003:209–40. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castro FG, Kellison JG, Boyd SJ et al. A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. J Mixed Methods Res 2010;4:342–60. 10.1177/1558689810382916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Badland HM, Schofield GM, Witten K et al. Understanding the Relationship between Activity and Neighbourhoods (URBAN) Study: research design and methodology. BMC Public Health 2009;9:224 10.1186/1471-2458-9-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Witten K, Blakely T, Bagheri N et al. Neighborhood built environment and transport and leisure physical activity: findings using objective exposure and outcome measures in New Zealand. Env Health Per 2012;120:971–7. 10.1289/ehp.1104584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kerr J, Sallis JF, Owen N et al. Advancing science and policy through a coordinated international study of physical activity and built environments: IPEN adult methods. J Phys Act Health 2013;10:581–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]