Abstract

Although μ-opioids have been reported to interact favorably with imidazoline I2 receptor (I2R) ligands in animal models of chronic pain, the dependence on the μ-opioid receptor ligand efficacy on these interactions had not been previously investigated. This study systematically examined the interactions between the selective I2 receptor ligand 2-(2-benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline hydrochloride (2-BFI) and three μ-opioid receptor ligands of varying efficacies: fentanyl (high efficacy), buprenorphine (medium-low efficacy), and 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-[(3′-isoquinolyl) acetamido] morphine (NAQ; very low efficacy). The von Frey test of mechanical nociception and Hargreaves test of thermal nociception were used to examine the antihyperalgesic effects of drug combinations in complete Freund’s adjuvant–induced inflammatory pain in rats. Food-reinforced schedule-controlled responding was used to examine the rate-suppressing effects of each drug combination. Dose-addition and isobolographical analyses were used to characterize the nature of drug-drug interactions in each assay. 2-BFI and fentanyl fully reversed both mechanical and thermal nociception, whereas buprenorphine significantly reversed thermal but only slightly reversed mechanical nociception. NAQ was ineffective in both nociception assays. When studied in combination with fentanyl, NAQ acted as a competitive antagonist (apparent pA2 value: 6.19). 2-BFI/fentanyl mixtures produced additive to infra-additive analgesic interactions, 2-BFI/buprenorphine mixtures produced supra-additive to infra-additive interactions, and 2-BFI/NAQ mixtures produced supra-additive to additive interactions in the nociception assays. The effects of all combinations on schedule-controlled responding were generally additive. Results consistent with these were found in experiments using female rats. These findings indicate that lower-efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonists may interact more favorably with I2R ligands than high-efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonists.

Introduction

Chronic pain is the single largest health care challenge facing the United States. It affects almost one-third of Americans, with an estimated annual cost of $600 billion in treatment and lost productivity, and severely impacts quality of life, second only to bipolar disorder as the leading cause of suicide among all medical illnesses (Asmundson and Katz, 2009; Elman et al., 2013; National Institutes of Health, 2013). With pain research underfunded and clinicians undertaught on the subject, the problem of pain management is exacerbated by the lack of significant breakthrough pharmacotherapies in the past 50 years (Kissin, 2010). Opioids are still the standard against which all analgesics are compared despite being plagued by side effects, including respiratory depression, sedation, and constipation. High abuse liability and analgesic tolerance on top of these side effects make opioid monotherapy strategies poorly suited to controlling chronic pain. A promising strategy for better treatments is combination therapy, which combines two or more drugs in a treatment regimen to increase intended therapeutic effects and decrease side effects that result from using higher doses of either drug alone (Smith, 2008; Gilron et al., 2013).

Many recent preclinical studies have established the imidazoline I2 receptor (I2R) as a promising target to treat chronic pain, both as monotherapy and when combined with µ-opioids (Ferrari et al., 2011; Lanza et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Thorn et al., 2015). The ability of I2R ligands to enhance µ-opioid agonist–induced analgesia in acute pain models, whereas these drugs alone do not produce antinociception (Li et al., 2011b; Thorn et al., 2011; Sampson et al., 2012), demonstrates a unique relationship between these two receptor systems. However, the pool of previous studies used a relatively limited number of µ-opioids (e.g., morphine, oxycodone) which have relatively high efficacy and are often accompanied by strong side effects (Meert and Vermeirsch, 2005). Given the positive interaction profiles from these former studies, an even more attractive regimen may be to combine I2R ligands with lower-efficacy µ-opioids which have milder side effects than their high-efficacy counterparts. In such a case, low-dose combinations of I2R ligands and low-efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonists may provide adequate analgesia with few side effects.

This study used a quantitative and systematic approach to examine the antihyperalgesic effects of the selective I2R agonist 2-(2-benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline hydrochloride (2-BFI) alone and in combination with opioids of varying efficacies using the von Frey test of mechanical nociception and the Hargreaves test of thermal nociception in adult male and female rats with complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA)–induced inflammatory pain. The μ receptor ligands studied were fentanyl (high efficacy), buprenorphine (medium-low efficacy), and 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-[(3′-isoquinolyl) acetamido] morphine (NAQ) (very low efficacy) (Li et al., 2009a). Dose-addition and isobolographical analyses were used to quantitatively examine the nature of the 2-BFI–opioid interactions. Additionally, we examined the effects of 2-BFI alone and in combination with these opioids on schedule-controlled responding in adult male rats to address the possibility of behavioral suppression with the observed antihyperalgesic effects.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Male (n = 128) and female (n = 19) Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) approximately 10 weeks old at the onset of the experiment were housed individually on a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle (behavioral experiments were conducted during the light period). Subjects had free access to water, except during testing sessions. Animals used in pain tests had free access to standard rodent chow in their home cages and were randomly assigned to different study groups (n = 6–7/group). Animals used in the schedule-controlled responding studies (n = 8 males) were provided with restricted access to food after their daily sessions, such that their body weights were maintained at 85% of their free-feeding counterparts. Animals were maintained and experiments were conducted in accordance with guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain (Zimmermann, 1983) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York (Buffalo, NY), and with the 2011 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC).

Induction of inflammatory pain.

Inflammatory pain was induced by CFA inoculation, as previously described (Li et al., 2014). In brief, 0.1 ml of CFA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing approximately 0.05 mg of Mycobacterium butyricum dissolved in paraffin oil was injected in the right foot pad (hind paw) of rats under isoflurane anesthesia (2% isoflurane mixed with 100% oxygen). The level of anesthesia was assessed by the loss of righting reflex. Since neither the course of hyperalgesia nor repeated treatment affects results (Li et al., 2014; Thorn et al., 2015), mechanical nociception tests were conducted 24 hours after CFA inoculation, and thermal nociception tests were conducted after an additional 24 hours (total of 48 hours post-CFA). In Figs. 1, 3, and 4, one group of rats was used to study the effects of each drug or drug combination in both assays of hyperalgesia.

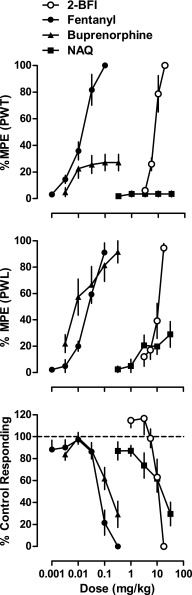

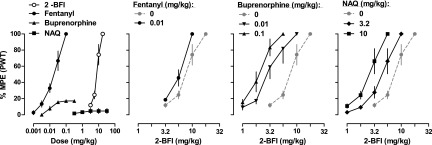

Fig. 1.

Percentage of maximum possible effects of 2-BFI and μ-opioid receptor ligands on CFA-induced mechanical nociception (n = 6/group) (top), CFA-induced thermal nociception (n = 6/group) (middle), and schedule-controlled responding (n = 8) (bottom). Ordinates: percentage of maximum possible effects (top and middle) or percentage of control responding rate (bottom); abscissa: drug doses (mg/kg, i.p.). PWT, paw withdrawal threshold.

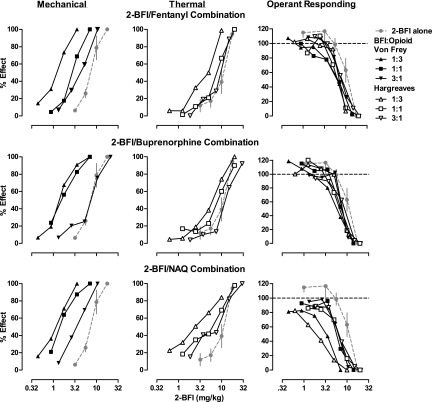

Fig. 3.

Effects 2-BFI alone or in combination with different proportions of fentanyl (top row), buprenorphine (middle row), or NAQ (bottom row) on CFA-induced mechanical nociception (n = 6/group) (left column), CFA-induced thermal nociception (n = 6/group) (middle column), and schedule-controlled responding (n = 8) (right column). Ordinates: percentage of maximum possible effects (left and middle columns) or percentage of control responding rate (right column); abscissa: dose of 2-BFI in the mixture (mg/kg, i.p.). Error bars are not shown for all combination studies for clarity.

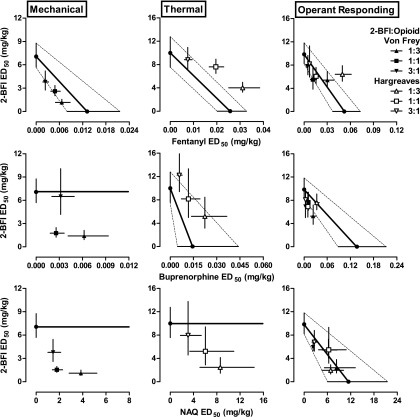

Fig. 4.

Isobolograms constructed from the data shown in Fig. 3. (Top row) Isobolograms for 2-BFI/fentanyl mixture for mechanical nociception (left), thermal nociception (middle), and responding rate (right). (Middle row) Isobolograms for 2-BFI/buprenorphine mixture for mechanical nociception (left), thermal nociception (middle), and responding rate (right). (Bottom row) Isobolograms for 2-BFI/NAQ mixture for mechanical nociception (left), thermal nociception (middle), and responding rate (right). Ordinate: ED50 value (95% CL) of 2-BFI (mg/kg); abscissa: ED50 value (95% CL) of μ-opioid receptor ligand (mg/kg).

Mechanical Hyperalgesia.

Mechanical hyperalgesia was measured using the von Frey filament consisting of calibrated filaments (1.4–26 g; North Coast Medical, Morgan Hill, CA). Rats (n = 6 per group) were placed in elevated plastic chambers with a wire mesh floor (IITC Life Science Inc., Woodland Hills, CA) immediately before the test. Filaments were applied perpendicularly to the medial plantar surface of the hind paw from below the mesh floor in an ascending order, beginning with the lowest filament (1.4 g). A filament was applied until buckling occurred and maintained for approximately 2 seconds. Mechanical thresholds [expressed in percentage of maximum possible effect (%MPE)] correspond to the lowest force that elicited a behavioral response (withdrawal of the hind paw) in at least two out of three applications. Tests were performed as cumulatively dosed multiple cycle procedures, where measurements were taken immediately prior to drug administration, then 20 minutes after drug administration before the next drug administration. These cycles continued until near 100% MPE was achieved (corresponding to 26 g) or until doses caused generalized behavioral suppression. Forces larger than 26 g would physically elevate the non–CFA-treated paw and did not reflect pain-like behavior. When 2-BFI and opioids were studied in combination in males, they were prepared in a mixture and administered as one injection. For the experiment examining the duration of action of NAQ for antagonizing a fixed dose of fentanyl-induced (0.1 mg/kg) antihyperalgesia as measured by the von Frey filament test, three groups of rats (n = 6/group, different pretreatments: saline, 3.2, or 5.6 mg/kg NAQ) were tested six times each with two drug-free days interspersed among the tests. The tests were always conducted 20 minutes after fentanyl administration, with pretreatments given before progressively increased pretreatment times. For the experiment examining the magnitude of antagonism of the fentanyl antinociception dose-effect curve by NAQ, control fentanyl dose-effect curves were first established in different groups of rats. Two days following the fentanyl test, NAQ was given as a single pretreatment 10 minutes before re-establishing the fentanyl dose-effect curve. When 2-BFI and opioids were studied in combination in females, each group of rats was tested three times, with each group only receiving one opioid. Two days were interspersed among the tests, and for each test, a single pretreatment of one opioid was given 10 minutes prior to establishing the 2-BFI dose-effect curve. Experimenters were blind to the treatments, and they received extensive training with this procedure to ensure accurate judgment of paw withdrawal responses and minimize experimenter bias.

Thermal Hyperalgesia.

Thermal hyperalgesia was measured using a plantar test apparatus (IITC Life Science Inc.), wherein the paw withdrawal latency (PWL) in response to a thermal stimulus was measured, as described previously (Hargreaves et al., 1988). The apparatus used a test unit containing a heat source that radiated a light beam. An adjustable angled mirror on the test unit was used to locate the correct targeting area on the paw. The beam source was set with an active intensity of 40%, an idle intensity of 10%, and a cutoff time of 20 s. PWL comprised the time from the start of the beam light until the animal withdrew the paw from the heat stimulus (reaction time was measured to 0.01 s). An acrylic six-chamber container was used to separate the rats that were placed on the glass base. Measurements were taken in duplicate approximately 1 minute apart, and the average was used for statistical analysis. When 2-BFI and opioids were studied in combination, they were prepared in a mixture and administered as one injection. Tests were performed as cumulatively dosed multiple-cycle procedures, where measurements were taken immediately prior to drug administration, then 20 minutes after drug administration before the next drug administration. These cycles continued until 100% MPE was achieved (corresponding to 20-second PWL) or until doses that caused generalized behavioral suppression were given.

Schedule-Controlled Responding.

Food-maintained operant responding experiments were conducted in commercially available chambers located within sound-attenuating, ventilated enclosures (Coulbourn Instruments Inc., Allentown, PA). Chambers contained two levers; responses on the inactive (right) lever were recorded and had no programmed consequence. Data were collected using Graphic State 3.03 software and an interface (Coulbourn Instruments Inc.). A single group of rats was used to test all drugs and drug combinations in the assay of schedule-controlled responding. Rats were trained to press the lever for food under a multiple-cycle procedure. Each cycle began with a 15-minute pretreatment period, during which the chamber was dark and responses had no programmed consequences, followed by a 5-minute response period, during which a light above the active (left) lever was illuminated and rats could receive a maximum of five food pellets (45 mg dustless precision pellets; Bio Serv Inc., Frenchtown, NJ) by responding on the active lever. Initially, a single response produced a food pellet; as performance improved, the response requirement was progressively increased across days to a final fixed ratio of 10. The light was terminated after the delivery of five food pellets or after 5 minutes had elapsed, whichever occurred first. Daily sessions consisted of six cycles, and rats had to satisfy the following criterion for 5 days before testing began: the daily response rate averaged across all six cycles within a session did not vary by more than 20% (An et al., 2012). After the first test, all tests were preceded by at least two consecutive saline training sessions that satisfied the same criterion. During testing, rats received a drug or drug combination administration at the beginning of each inactive period in a cumulatively dosed manner until the rate was reduced to less than 20% of the saline control rate.

Data Analyses.

Antihyperalgesic effects of the drugs and drug combinations studied were quantified for each animal as %MPE for each dose. The following formula was used to quantify %MPE: %MPE = [postdrug value for a behavioral response (grams or seconds) − predrug value for a behavioral response] / (pre-CFA value − predrug value) × 100. To construct antihyperalgesic dose-effect curves, %MPEs were averaged within each group (±S.E.M.) and plotted as a function of dose. Rate of schedule-controlled responding is expressed as a percentage of the saline control response rate. For each cycle of a drug test, the control response rate for an individual rat was the average response rate of the corresponding cycle from two saline sessions immediately prior to the test. These percentages were averaged across eight rats (±S.E.M.) and plotted as a function of dose. Log(ED50) (±95% confidence limits [CLs]) values were determined from the %MPE for each animal within a particular group and averaged within the group to calculate the ED50 values for each drug for each behavioral assay.

For the study that examined combinations of NAQ and fentanyl, dose ratios were determined for each rat by dividing the ED50 values for fentanyl studied in combination with each dose of NAQ by the ED50 value for fentanyl studied alone. Schild analysis was conducted as described previously (Li et al., 2009b) using the method of Arunlakshana and Schild (1959). The Schild plot was constructed by plotting the log of the dose ratio (agonist with antagonist divided by agonist alone) − 1 as a function of the negative log dose of antagonist (moles per kilogram). A straight line was simultaneously fitted to the Schild plot using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and the following equation: log (dose ratio − 1) = −log (molar dose of antagonist) × slope + intercept. Apparent affinity (pA2) values and 95% CLs with unconstrained slopes were determined for each subject. Slopes of Schild plots were considered to conform to unity when the 95% CL included −1 and did not include 0 (Paronis and Bergman, 1999).

For the study that examined the interactions between 2-BFI and opioids in male rats, a fixed proportion dose-addition analysis method was used as described previously (An et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011a,b, 2014). For this analysis, two drugs were combined in fixed proportions (1:1, 1:3, and 3:1) and administered using the cumulative dosing procedure as described earlier. The actual doses of the drugs in the combination were determined by the relative potencies of each drug (based on the ED50 values) in each assay. For example, the 1:1 ratio of 2-BFI/fentanyl consisted of 1 × ED50 of 2-BFI (7.08 mg/kg) and 1 × ED50 of fentanyl (0.013 mg/kg) from the mechanical nociception test. Fractions of this mixture (the combined 0.125 ×, 0.25 ×, 0.5 ×, and 1 × ED50 values of 2-BFI and fentanyl) were administered consecutively by a cumulative dosing procedure to complete one dose-effect curve test. By this method, the 1:3 ratio consisted of 0.5 × ED50 of 2-BFI and 1.5 × ED50 of fentanyl, and the 3:1 ratio consisted of 1.5 × ED50 of 2-BFI and 0.5 × ED50 of fentanyl. In some cases, the ED50 of a drug could not be calculated due to low efficacy. For buprenorphine, combinations of 2-BFI/buprenorphine for the assay of mechanical nociception were based on the ED50 ratio of these two drugs alone in the assay of thermal nociception. For NAQ, combinations of 2-BFI/NAQ for the assays of mechanical and thermal nociception were based on the ED50 ratio of these two drugs alone in schedule-controlled responding. The shared dose-effect curves of the drug mixtures were determined, and the individual ED50 values of the two drugs in a mixture were calculated. Isobolograms were constructed to visually represent the nature of the drug interactions as additive, supra-additive, or infra-additive. Dose-addition analysis was also performed as described previously (Tallarida, 2000). When both drugs were active in an assay, expected additive ED50 values (±95% CL) (Zadd) were calculated from the equation Zadd = fA + (1 − f)B, where A is the ED50 of 2-BFI alone, B is the ED50 of the opioid alone, and f is the fractional multiplier of A in the computation of the additive total dose (e.g., f = 0.5 when fixed ratio was 1:1). When only one drug was active in an assay, the hypothesis of additivity predicts that the inactive drug should not contribute to the effects of the mixture, and the equation reduces to Zadd = A/ρA, where ρA is the proportion of 2-BFI in the total drug dose. Experimental ED50 values (±95% CL) (Zmix) were determined from the 1:3, 1:1, and 3:1 combinations and were defined as the sum of the ED50 values of both drugs in the combination. Effects were considered significant if the Zadd and Zmix 95% confidence limits did not overlap. If Zmix was significantly less than Zadd, the interaction was considered supra-additive. If Zmix was significantly greater than Zadd, the interaction was considered infra-additive.

To evaluate drug interactions across assays, the relative potency of each drug or drug combination in the assay of schedule-controlled responding and mechanical or thermal nociception was quantified according to the following equation: dose ratio = Zmix in schedule-controlled responding ÷ Zmix in thermal or mechanical nociception (Negus et al., 2008). A dose ratio >1 indicates that the drug or mixture tended to be more potent in an assay of nociception, whereas a dose ratio <1 indicates that the drug or mixture tended to be more potent in the assay of schedule-controlled responding. The dose ratio of each drug or drug combination was considered to be statistically significant if the 95% confidence limits of the Zmix values in the two procedures did not overlap.

For the study that examined the interactions between 2-BFI and opioids in female rats, the ED50 values (±95% CL) of 2-BFI with opioid pretreatment were compared with the ED50 values (±95% CL) of 2-BFI without opioid pretreatment. If the confidence limits did not overlap, the effect was considered significant.

Drugs.

2-BFI hydrochloride was synthesized according to standard procedures (Ishihara and Togo, 2007), as was NAQ (Li et al., 2009a). Buprenorphine hydrochloride and fentanyl hydrochloride were provided by Research Technology Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (Rockville, MD). All drugs were dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered intraperitoneally.

Results

CFA injection into the right hindpaw of rats produced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia that persisted well beyond the duration of the experiments of this study as described previously (Li et al., 2014; Thorn et al., 2015). Mean pre-CFA baseline values (±S.E.M.) of 25.1 ± 0.9 g and 19.42 ± 0.34 seconds for paw withdrawal threshold and PWL, respectively, were reduced to average post-CFA values of 5.9 ± 0.2 g and 8.41 ± 0.31 seconds. To demonstrate the antinociceptive effectiveness of 2-BFI, fentanyl, buprenorphine, and NAQ, we performed multiple-cycle cumulatively dosed tests of each drug alone in the assays of mechanical and thermal nociception in separate groups of rats for each drug (Fig. 1). 2-BFI produced dose-dependent antihyperalgesia and elicited >90% MPE in both assays at 17.8 mg/kg. Fentanyl also produced dose-dependent antihyperalgesia and elicited >90% MPE in both assays at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg. Buprenorphine lost dose dependence and reached a peak effect of 27.1 ± 6.1% MPE in the assay of mechanical nociception, reflecting its lower efficacy property at the µ-opioid receptor. However, buprenorphine dose dependently increased the paw withdrawal threshold and reached >90% MPE at 1.0 mg/kg in the thermal nociception test (Fig. 1). This discrepancy between nociceptive assays for buprenorphine has been documented previously (Meert and Vermeirsch, 2005). NAQ produced no antihyperalgesia (3.5 ± 2.2%) in the mechanical test and modest but statistically significant antihyperalgesia (29.0 ± 9.8%) in the thermal nociception test up to a dose of 32 mg/kg (Fig. 1). Higher doses were not pursued due to behavioral suppression. The ED50 values of the drugs alone for the nociceptive assays are presented in Table 1. To address generalized behavioral suppression (e.g., motor impairment) that may influence the results of these two assays, we also investigated the response rate–suppressing effect of each drug. The average control response rate (±S.E.M.), determined on the 2 days preceding test days throughout the study, was 0.71 ± 0.02 responses/s. Response rates across the six cycles of the procedure were very stable (0.72 ± 0.04, 0.72 ± 0.04, 0.72 ± 0.04, 0.70 ± 0.04, 0.70 ± 0.05, and 0.68 ± 0.05 responses/s, respectively). All four drugs dose dependently decreased the rate of responding, and the ED50 values of the drugs alone for this assay are also presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

ED50 values (95% CL) for individual drugs in the assays of mechanical nociception, thermal nociception, and food-maintained schedule-controlled responding

| Treatment | Mechanical | Thermal | Operant Responding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-BFI | 7.08 (5.71, 8.77) | 9.99 (7.60, 13.12) | 9.85 (8.22, 11.80) |

| Fentanyl | 0.013 (0.008, 0.022) | 0.026 (0.020, 0.033) | 0.052 (0.037, 0.073) |

| Buprenorphine | >0.32 | 0.014 (0.0048, 0.044) | 0.14 (0.09, 0.22) |

| NAQ | >32 | >32 | 11.43 (6.09, 21.45) |

Relative potency values between 2-BFI and the opioids were determined. The values for 2-BFI/fentanyl were 545:1 for the mechanical nociception assay and 384:1 for the thermal nociception assay. The value used for 2-BFI/buprenorphine was 714:1 for both nociception assays since an ED50 value for buprenorphine could not be calculated in the mechanical nociception test. The value used for 2-BFI/NAQ was 0.86:1 since an ED50 value for NAQ could only be calculated in the schedule-controlled responding experiment. These relative potencies for each µ-opioid receptor ligand in comparison with 2-BFI were then used to determine the proportions of each in drug mixtures.

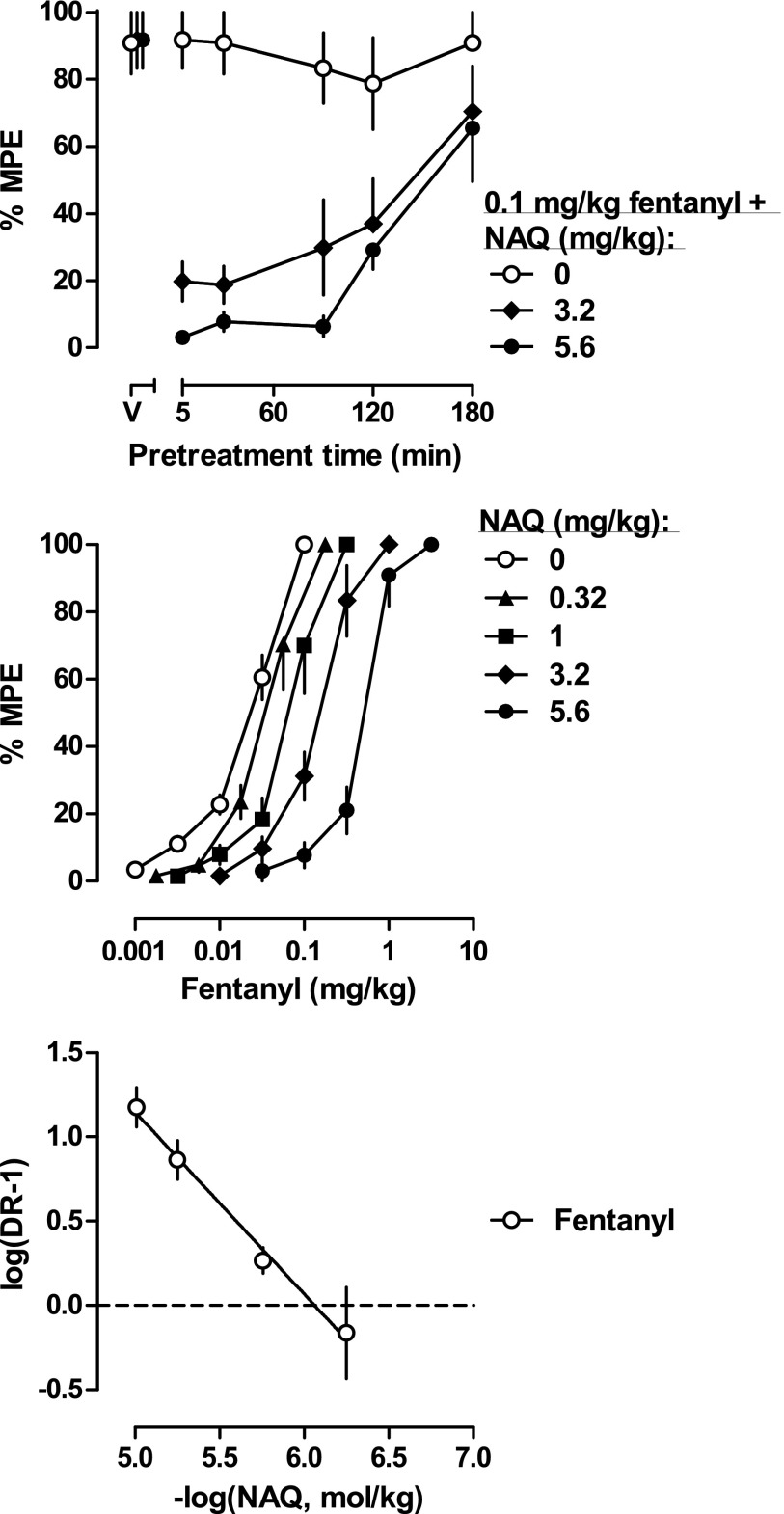

To confirm NAQ acts at the µ-opioid receptor in vivo, and to gain more information about its action, we tested it in combination with fentanyl in the mechanical nociception assay. Different pretreatment times (5, 30, 60, and 120 minutes) with 3.2 or 5.6 mg/kg NAQ were able to antagonize the antihyperalgesic effects of 0.1 mg/kg fentanyl (Fig. 2, top). Because NAQ alone was ineffective in the mechanical nociception assay, we next examined whether NAQ acted as an antagonist at the µ-receptor. We performed a Schild analysis by establishing full fentanyl dose-effect curves following injections of several doses of NAQ (Fig. 2, middle). NAQ dose dependently shifted the fentanyl dose-effect curve rightward in a parallel manner. The ED50 values of fentanyl with NAQ were compared with the ED50 values of fentanyl alone to generate a series of dose ratios (Table 2). The Schild plot was constructed as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 2, bottom). The average of the slopes of the individual regression lines was not significantly different from −1 (unity), suggesting that NAQ blocked the antinociceptive effect of fentanyl in a simple, reversible, and competitive manner, and that in this assay, NAQ acted as a competitive µ receptor antagonist. The apparent pA2 value of NAQ was 6.19 (5.90–6.49).

Fig. 2.

(Top) Duration of action of NAQ antagonism of 0.1 mg/kg fentanyl-induced antinociception (n = 6/group). Ordinates: percentage of maximum possible effect; abscissa: pretreatment time of NAQ injection. (Middle) Percentage of maximum possible effects of fentanyl alone (n = 24) or in combination with different doses of NAQ (n = 6/group). Ordinates: percentage of maximum possible effect; abscissa: fentanyl dose (mg/kg, i.p.). (Bottom) Schild plot constructed from the same data as the middle panel. Abscissa: negative log of the dose of NAQ in moles per kilogram of body weight; ordinate: log(dose ratio – 1). The fentanyl alone dose-effect curve represented a pool of 24 rats from four groups of rats, as the ED50 values of fentanyl were not different among the groups.

TABLE 2.

ED50 values (95% CL) for fentanyl alone and in combination with NAQ in the assay of mechanical nociception and the dose ratios between them

| Treatment | ED50 (95% CL) | Dose Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl alone | 0.018 (0.012, 0.027) | |

| 0.32 NAQ/fent | 0.032 (0.021, 0.049) | 1.80 |

| Fentanyl alone | 0.021 (0.012, 0.035) | |

| 1 NAQ/fent | 0.061 (0.039, 0.098) | 2.90 |

| Fentanyl alone | 0.016 (0.009, 0.030) | |

| 3.2 NAQ/fent | 0.137 (0.087, 0.216) | 8.50 |

| Fentanyl alone | 0.028 (0.023, 0.036) | |

| 5.6 NAQ/fent | 0.459 (0.327, 0.644) | 16.12 |

fent, fentanyl.

Figure 3 shows the dose-effect curves for 2-BFI administered alone and in combination with different proportions of each µ-opioid. The left panels show results of the mechanical nociception test, the middle panels show results of the thermal nociception test, and the right panels show the results of the schedule-controlled responding assay. The ED50 values of drugs in the dose-effect curves were calculated and used to perform isobolographical analyses (Fig. 4). Dose-addition analysis was also performed. Table 3 shows predicted Zadd values and empirically determined Zmix values for each drug mixture. From these quantitative tests, we were able to classify the nature of drug-drug interactions for each mixture. In general, 2-BFI/fentanyl mixtures produced effects consistent with those expected. Exceptions were 1:1 and 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl mixtures in the thermal nociception test, which produced infra-additive interactions, and 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl doses from the thermal nociception test when used for schedule-controlled responding, which also produced infra-additive effects. 2-BFI/buprenorphine mixtures generally produced additive effects. Exceptions were in the mechanical nociception test, in which 1:3 and 1:1 combinations produced supra-additive effects. 2-BFI/NAQ mixtures generally produced additive effects, with the exception of all mixtures in the mechanical nociception test and the 1:3 mixture in the thermal nociception test, which produced supra-additive effects.

TABLE 3.

Expected additive ED50 values (Zadd), actual (experimentally determined) ED50 values (Zmix), and the ratio of expected/actual ED50 values for drug mixtures for antinociception and operant responding in rats

| Mixture | Zadd (95% CL) | Zmix (95% CL) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical nociception test | ||

| 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl | 1.78 (1.43, 2.21) | 1.19 (0.90, 1.58) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 3.54 (2.86, 4.40) | 2.62 (2.05, 3.36) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 5.31 (4.28, 6.58) | 3.80 (2.77, 5.21) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 7.10 (5.73, 8.81) | 1.42 (0.94, 2.13)a |

| 1:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 7.09 (5.72, 8.78) | 1.88 (1.25, 2.84)a |

| 3:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 7.08 (5.71, 8.77) | 6.50 (4.19, 10.08) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ | 31.70 (25.57, 39.29) | 4.95 (3.66, 6.71)a |

| 1:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 15.29 (12.33, 18.95) | 3.32 (2.59, 4.24)a |

| 3:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 9.81 (7.92, 12.16) | 5.23 (3.62, 7.56)a |

| Thermal nociception test | ||

| 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl | 2.52 (1.92, 3.30) | 4.05 (3.28, 5.01)b |

| 1:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 5.01 (3.81, 6.58) | 7.62 (6.50, 8.95)b |

| 3:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 7.50 (5.71, 9.85) | 8.83 (7.12, 10.96) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 2.51 (1.90, 3.31) | 5.19 (3.18, 8.48) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 5.00 (3.80, 6.58) | 8.16 (4.99, 13.35) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 7.49 (5.70, 9.85) | 12.23 (9.41, 15.91) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ | 44.77 (34.08, 58.83) | 11.07 (6.60, 18.59)a |

| 1:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 21.57 (16.42, 28.34) | 11.28 (6.26, 20.33) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 13.85 (10.54, 18.20) | 11.02 (6.36, 19.10) |

| Operant responding | ||

| Mixtures in mechanical nociception test | ||

| 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl | 5.60 (4.67, 6.72) | 5.51 (3.87, 7.84) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 7.04 (5.87, 8.43) | 5.43 (4.26, 6.95) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 8.43 (7.04, 10.11) | 7.81 (6.32, 9.67) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 8.52 (7.11, 10.22) | 5.27 (3.86, 7.19) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 8.97 (7.48, 10.75) | 6.97 (5.58, 8.70) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 9.41 (7.85, 11.27) | 6.93 (5.02, 9.57) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ | 11.04 (6.62, 19.04) | 10.73 (6.77, 17.00) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 10.64 (7.16, 16.63) | 11.48 (8.31, 15.85) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 10.25 (7.69, 14.21) | 8.22 (7.34, 9.20) |

| Mixtures in thermal nociception test | ||

| 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl | 4.28 (3.57, 5.13) | 6.28 (5.23, 7.53)b |

| 1:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 6.13 (5.12, 7.36) | 6.08 (4.85, 7.63) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 7.99 (6.67, 9.58) | 8.19 (5.94, 11.31) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 8.52 (7.11, 10.22) | 7.63 (6.40, 9.11) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 8.97 (7.48, 10.75) | 6.92 (5.12, 9.39) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 9.41 (7.85, 11.27) | 8.09 (6.50, 10.06) |

| 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ | 11.04 (6.62, 19.04) | 8.81 (5.94, 13.07) |

| 1:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 10.64 (7.16, 16.63) | 11.81 (6.91, 20.18) |

| 3:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 10.25 (7.69, 14.21) | 9.42 (7.28, 12.20) |

Zmix confidence limits do not overlap with Zadd confidence limits: Zmix lower than Zadd (supra-additivity).

Zmix confidence limits do not overlap with Zadd confidence limits: Zmix higher than Zadd (infra-additivity).

Table 4 shows dose ratios for the potency of each drug and drug combination in decreasing the rate of operant responding versus producing mechanical and thermal antihyperalgesia. 2-BFI alone was slightly more potent in the assay of mechanical nociception, but roughly equipotent in the assay of thermal nociception. Fentanyl alone was significantly more potent in both assays of nociception. Buprenorphine was significantly more potent in the assay of thermal nociception, but dose ratios for buprenorphine in the assay of mechanical nociception and NAQ in either assay of nociception could not be calculated due to low efficacy.

TABLE 4.

Dose ratios of 2-BFI alone, opioids alone, and 2-BFI+opioid mixtures to produce antinociception versus suppression of operant responding

| Mechanical | Thermal | |

|---|---|---|

| 2-BFI alone | 1.39 | 0.99 |

| Fentanyl alone | 4.00* | 2.00* |

| 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl | 4.63a,* | 1.55* |

| 1:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 2.07* | 0.80 |

| 3:1 2-BFI/fentanyl | 2.06* | 0.93 |

| Buprenorphine alone | <0.43 | 10.00 |

| 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 3.71a,* | 1.47* |

| 1:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 3.96a,* | 0.85 |

| 3:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine | 1.07 | 0.66 |

| NAQ alone | <0.35 | <0.35 |

| 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ | 2.17a,* | 0.80 |

| 1:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 3.46a,* | 1.05a |

| 3:1 2-BFI/NAQ | 1.57a | 0.85 |

Dose ratio for a combination is greater than dose ratio for either component drug.

Drug or drug mixture was significantly more potent in the assay of nociception as determined by nonoverlapping confidence limits of Zmix values.

Mixtures of 2-BFI and fentanyl tended to produce dose ratios >1. The effect was significant for both nociceptive assays in the 1:3 2-BFI/fentanyl combination, although the ratios were not much different from those of fentanyl alone. The other 2-BFI/fentanyl combinations produced dose ratios >2 in the assay of mechanical nociception and were roughly equipotent in the assay of thermal nociception. Mixtures of 2-BFI and buprenorphine tended to produce dose ratios >1. The effect was significant for both assays of nociception in the 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine combination; however, the dose ratio in the thermal nociception assay was much lower than that of buprenorphine alone. The 1:1 2-BFI/buprenorphine combination produced a statistically significant dose ratio of 3.96 in the assay of mechanical nociception, but these two drugs were roughly equipotent in the remaining assays. Mixtures of 2-BFI/NAQ tended to produce dose ratios of roughly 1. In the assay of mechanical nociception, the 1:3 and 1:1 combinations were significantly more potent, but in all other cases, the results were roughly equipotent. Thus, whereas dose-addition analysis indicated that some 2-BFI/buprenorphine and 2-BFI/NAQ combinations produced supra-additive effects in assays of nociception and additive effects in the assay of schedule-controlled responding, dose-ratio analysis also revealed significant differences in the relative potencies of some of these mixtures (e.g., 1:3 and 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ), but not others (e.g., 3:1 2-BFI/NAQ), to produce two different behavioral effects.

Because chronic pain was reported to be mediated differently in male than female rodents (Sorge et al., 2015), and since gender differences may exist in µ-opioid receptor–mediated analgesia (Cicero et al., 1996; Craft et al., 2001; Stoffel et al., 2005; Peckham and Traynor, 2006), we investigated whether the aforementioned findings applied to female rats as well. In CFA-treated female rats, the ED50 values (95% CL) of 2-BFI and fentanyl were 7.62 (6.10, 9.55) and 0.017 (0.010, 0.027), respectively. These values overlapped with those of the male rats in this study. The maximum effect levels (±S.E.M.) of buprenorphine and NAQ were 17.1 ± 1.5% and 4.7 ± 3.2%, respectively (Fig. 5, left panel). To compare these values to those determined in male rats, data were converted to maximum effect level (95% CL). The maximum effect level of buprenorphine in females [17.1% (14.3, 20.0%)] overlapped with that of the male rats [27.1% (15.1, 39.1%)], and the maximum effect level of NAQ in females [4.7% (−1.5, 10.9%)] also overlapped with that of the male rats [3.5% (−0.9, 7.9)]. To investigate 2-BFI–opioid interactions in females, a single 10-minute pretreatment of a µ-opioid receptor ligand was given before determining the 2-BFI dose-effect curve. Fentanyl, buprenorphine, and NAQ were all able to shift the dose-effect curve of 2-BFI leftward to a level of statistical significance (Fig. 5, three right panels). Table 5 gives the ED50 values of 2-BFI in each combination and the dose-ratio values.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of maximum possible effects of 2-BFI and μ-opioid receptor ligands on CFA-induced mechanical nociception in female rats (n = 6–7/group) (left). Enhancement of 2-BFI–induced antinociception by fentanyl (middle left), buprenorphine (middle right), or NAQ (right). Ordinates: percentage of maximum possible effects (top and middle) or percentage of control responding rate (bottom); abscissa: drug doses (mg/kg, i.p.) (left) or dose of 2-BFI (mg/kg, i.p.) (three right panels). PWT, paw withdrawal threshold.

TABLE 5.

ED50 values (95% CL) of 2-BFI alone and in combination with the varied-efficacy opioids and the dose ratios between them in female rats

| Treatment | ED50 (95% CL) | Dose Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 2-BFI alone | 7.62 (6.10, 9.55) | |

| 0.01 Fentanyl + 2-BFI | 5.25 (4.68, 5.88)a | 1.45 |

| 0.01 Bup + 2-BFI | 2.86 (2.05, 3.99)a | 2.66 |

| 0.1 Bup + 2-BFI | 1.95 (1.50, 2.54)a | 3.91 |

| 3.2 NAQ + 2-BFI | 4.21 (3.23, 5.51)a | 1.81 |

| 10 NAQ + 2-BFI | 2.40 (1.89, 3.06)a | 3.18 |

Bup, buprenorphine.

Confidence limits of combination do not overlap with confidence limits of 2-BFI alone.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that low-efficacy µ-opioid receptor ligands were able to selectively enhance 2-BFI–induced antihyperalgesia in a rat model of persistent inflammatory pain. Buprenorphine and NAQ, two low-efficacy µ-opioid receptor ligands that were ineffective in at least one of the nociceptive assays, produced supra-additive effects in one or both of the nociceptive assays when combined with 2-BFI. In contrast, the full µ-opioid receptor agonist fentanyl produced additive to infra-additive effects in all assays when combined with 2-BFI. Consistent results were found in experiments using female subjects. These results suggest that lower-efficacy μ-opioid receptor ligands may be useful to combine with imidazoline I2R ligands for pain management and represent an advantage over current analgesics, both for therapeutic efficacy and when considering side effects that plague strong opioid compounds. For example, I2R ligands were shown to attenuate repeat opioid treatment–induced antinociceptive tolerance and dependence (Thorn et al., 2016).

Previous investigations of analgesic drug combinations involving I2R ligands have focused on high-efficacy µ-opioids and have found additive to supra-additive interactions that appear to be dependent on the I2R ligand (Lanza et al., 2014; Thorn et al., 2015) or the behavioral tests (Li et al., 2011b, 2014). The interactions between 2-BFI and fentanyl in the mechanical nociception and schedule-controlled responding assays of the present study largely agree with previous reports, in which 2-BFI combined with morphine or oxycodone reversed CFA-induced mechanical nociception in a simple additive manner (Li et al., 2014; Thorn et al., 2015). The additive to infra-additive interactions between 2-BFI and fentanyl in the thermal nociception test were somewhat unexpected, although comparable interactions had not been previously examined for thermal nociception. These results suggest that, overall, 2-BFI and high-efficacy µ-opioid receptor agonists do not produce supra-additive interactions in the CFA-induced chronic inflammatory pain model.

The goal of this study was to examine the role that µ-opioid receptor efficacy plays in determining the antinociceptive interactions between 2-BFI and opioids. To this end, we used the compound buprenorphine as an intermediate-efficacy µ-opioid receptor ligand and the compound NAQ as a very low-efficacy µ-opioid receptor ligand. NAQ, although not extensively characterized in vivo, was reported to be a selective and very low-efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonist, capable of antagonizing several morphine-elicited behavioral effects (Li et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2014). In line with this previous characterization, NAQ produced little effect in the mechanical nociception test and antagonized fentanyl-induced hyperalgesia in a manner consistent with that of a competitive µ-opioid receptor antagonist. However, this did not preclude NAQ from displaying a modest degree of efficacy in the thermal nociception test. Efficacy differences between mechanical and thermal nociceptive assays have been documented before, with buprenorphine as one example in the present and previous investigations (Meert and Vermeirsch, 2005). Such differences are likely due to the varying efficacy demands of the pain assays. Surprisingly, however, buprenorphine and NAQ enhanced the antihyperalgesic effects of 2-BFI to a greater degree than fentanyl did. Moreover, NAQ elicited supra-additive effects in one or even both nociceptive assays (e.g., 1:3 2-BFI/NAQ) while eliciting only additive effects in the schedule-controlled responding assay. These results seem to indicate that combinations of low-efficacy µ-opioid receptor ligands and 2-BFI are superior to combinations of high-efficacy µ-opioid receptor ligands and 2-BFI for the selective reduction CFA-induced hyperalgesia.

Our experiments in female subjects used a different design than in male subjects (fixed-dose µ-opioid pretreatment) and were conducted in only one assay (mechanical nociception). These factors permit a more restricted degree of interpretation, analysis, and comparison with our experiments in male rats. Nonetheless, a greater leftward shift was produced by pretreatments with buprenorphine or NAQ than with fentantyl, and the findings in female rats appear to be consistent with those in male rats. Although recent studies have suggested the importance of gonadal steroids in pain sensitivity (Kumar et al., 2015; Sorge et al., 2015; Taves et al., 2015) and opioid analgesia (Cicero et al., 1996; Craft et al., 2001; Stoffel et al., 2005; Peckham and Traynor, 2006), the current investigation did not find significant differences between males and females for any drug alone in the mechanical nociception test. One possibility for the lack of observed differences is that the impact of gonadal hormones on the drug effect was small, which was lost in averaged group data.

Numerous studies have examined interactions between µ-opioid receptor agonists and various classes of adjunct compounds in assays of nociception and schedule-controlled responding. The following are among the adjuncts that have been demonstrated to selectively enhance µ-opioid antinociception over rate suppression: selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (Gatch et al., 1998; Banks et al., 2010), a δ-opioid receptor agonist (Stevenson et al., 2003), an N-Methyl-D-aspartate antagonist (Fischer and Dykstra, 2006), metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 and metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 antagonists (Fischer et al., 2008), and cannabinoids (Maguire and France, 2014). Interestingly, in some cases, greater antinociceptive enhancement of low- compared to high-efficacy µ agonists was reported (Gatch et al., 1998; Banks et al., 2010), whereas in other cases, the opposite was found (Maguire and France, 2014). These studies represent promising potential novel pain therapies; however, subsequent clinical testing of these therapies has not been performed. Our study with the I2R ligand 2-BFI adds to the list of potential µ-opioid receptor adjuncts that could be used to treat chronic pain. More specifically, 2-BFI produced results similar to those in the studies using serotonin uptake inhibitors, where lower-efficacy µ agonists were enhanced more greatly than high-efficacy µ agonists. This puts forth the additional attractive option to use low-efficacy µ agonists, which likely have milder side effects and lower abuse liability than their higher-efficacy counterparts. These promising findings have not been tested in controlled clinical trials, which reflects the reality that preclinical findings are way ahead of relevant clinical studies and highlights the necessity of expedited translational studies to eventually introduce these potentially valuable pain adjuvants into clinical practice. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that NAQ has sufficient efficacy to produce weak facilitation of intracranial self-stimulation in morphine-naive rats (Altarifi et al., 2015), suggesting the possibility of its abuse potential. Abuse potential of opioids is one important factor that limits its adequate clinical use. Future studies that examine the abuse liability of the I2R agonists and opioid combinations will be of interest.

To further analyze the interactions between 2-BFI and opioids across the different assays (assuming that nociception assays are related to therapeutic effects and the operant rate-suppressing effect is related to unwanted effects), a dose-ratio analysis was conducted. As seen from Table 4, several inferences can be drawn. First, the interactions between 2-BFI and opioids are dependent on the efficacy of opioids, with the most favorable interactions seen for 2-BFI–NAQ combinations and least favorable interactions seen for 2-BFI–fentanyl. Second, the interactions were dependent on the nociceptive assays, with more favorable interactions seen in the assay of mechanical nociception and generally unfavorable interactions seen in the assay of thermal nociception. Third, the interactions were dependent on the proportion of 2-BFI–opioid, with more favorable interactions seen when the 2-BFI proportion was low (1:3) than when it was high (3:1). Last, none of the 2-BFI–opioid interactions produced dose ratios better than fentanyl alone. However, as discussed earlier, since fentanyl use is related to a high rate of unwanted effects, the combination of 2-BFI with low-efficacy opioids (e.g., 1:3 2-BFI/buprenorphine and 1:1 2-BFI/NAQ) may still be clinically beneficial with adequate analgesia and limited unwanted effects.

Although the results of this study are exciting, it is difficult to speculate on the interacting mechanism(s) of these receptor systems that would lead to these findings. Indeed, more is currently known about I2R-mediated behavioral effects and its interactions with other drug targets than about its underlying mechanisms. Previous reports have asserted that a portion of I2Rs exist on a population of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) (Sastre and Garcia-Sevilla, 1993; Tesson et al., 1995; Paterson et al., 2007). If true, this might easily explain an array of I2R-related effects. However, it was shown that deprenyl, which is both an I2R ligand and MAO-B inhibitor, but not lazabemide, which is only an MAO-B inhibitor, enhanced morphine antinociception (Sánchez-Blázquez et al., 2000). This suggests that, although a portion of I2Rs seem to inhibit MAO-B, this is not likely to account for I2/μ receptor interactions. Another interesting possible explanation is the participation of G proteins. Sánchez-Blázquez and colleagues (2000) found that pretreatment of pertussis toxin, which impairs GTP-binding Gi/o proteins, blocked the ability of I2Rs to enhance morphine analgesia in mice. To date, no further investigation regarding the relation of I2Rs to G proteins to confirm or deny this possibility has been performed. Last, central glial activity may also play a role in these interactions. Some negative consequences of chronic opioid treatment regimens, such as tolerance and hyperalgesia, have been hypothesized to be mediated by activated spinal microglia (Horvath et al., 2010; Ferrini et al., 2013). Previous reports and our unpublished observations suggest that I2R ligands are capable of attenuating microglial activation in various experimental scenarios (Wang et al., 2009; Ahn et al., 2012). Thus, the attenuation of opioid tolerance by I2R ligand treatment and the selective enhancement of opioid analgesia may fit this hypothesis. Whether this model could explain the acute effects investigated in the present study remains to be seen. Further, although most literature on this subject has used morphine as the prototypical opioid ligand, important differences in addition to efficacy may exist between morphine and compounds such as buprenorphine and NAQ. Together, it seems premature to speculate underlying mechanisms that explain the observed efficacy-dependent interactions of µ-opioid receptor agonists and 2-BFI.

In summary, this study found that the varied efficacy of μ-opioid receptor ligands (fentanyl > buprenorphine > NAQ) exhibited differing antinociceptive interactions with the selective I2R ligand 2-BFI. In general, opioids with higher efficacy demonstrated additive interactions when studied with 2-BFI for antinociception, whereas opioids with low efficacy demonstrated supra-additive interactions with 2-BFI for antinociception. Results consistent with these were found in experiments using female rats. These findings indicate that lower-efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonists may interact more favorably with I2R ligands than high-efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonists. Since these results appear to be consistent across a relatively broad range of proportions, such combinations containing lower-efficacy µ-opioid receptor agonists likely represent an improvement over the strong opioid compounds currently used to treat chronic pain.

Abbreviations

- CFA

complete Freund’s adjuvant

- CL

confidence limit

- I2R

I2 receptor

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- MPE

maximum possible effect

- NAQ

17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-[(3′-isoquinolyl) acetamido] morphine

- PWL

paw withdrawal latency

- 2-BFI

2-(2-benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline hydrochloride

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Siemian, Li.

Conducted experiments: Siemian, Li.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Obeng, Yan Zhang, Yanan Zhang.

Performed data analysis: Siemian, Li.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Siemian, Li.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant R01DA034806] and the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant 81373390]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ahn SK, Hong S, Park YM, Choi JY, Lee WT, Park KA, Lee JE. (2012) Protective effects of agmatine on lipopolysaccharide-injured microglia and inducible nitric oxide synthase activity. Life Sci 91:1345–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altarifi AA, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Selley DE, Negus SS. (2015) Effects of the novel, selective and low-efficacy mu opioid receptor ligand NAQ on intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:815–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An XF, Zhang Y, Winter JC, Li JX. (2012) Effects of imidazoline I(2) receptor agonists and morphine on schedule-controlled responding in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 101:354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunlakshana O, Schild HO. (1959) Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br Pharmacol Chemother 14:48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJ, Katz J. (2009) Understanding the co-occurrence of anxiety disorders and chronic pain: state-of-the-art. Depress Anxiety 26:888–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Rice KC, Negus SS. (2010) Antinociceptive interactions between Mu-opioid receptor agonists and the serotonin uptake inhibitor clomipramine in rhesus monkeys: role of Mu agonist efficacy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Nock B, Meyer ER. (1996) Gender-related differences in the antinociceptive properties of morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 279:767–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Tseng AH, McNiel DM, Furness MS, Rice KC. (2001) Receptor-selective antagonism of opioid antinociception in female versus male rats. Behav Pharmacol 12:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I, Borsook D, Volkow ND. (2013) Pain and suicidality: insights from reward and addiction neuroscience. Prog Neurobiol 109:1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari F, Fiorentino S, Mennuni L, Garofalo P, Letari O, Mandelli S, Giordani A, Lanza M, Caselli G. (2011) Analgesic efficacy of CR4056, a novel imidazoline-2 receptor ligand, in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. J Pain Res 4:111–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrini F, Trang T, Mattioli TA, Laffray S, Del’Guidice T, Lorenzo LE, Castonguay A, Doyon N, Zhang W, Godin AG, et al. (2013) Morphine hyperalgesia gated through microglia-mediated disruption of neuronal Cl⁻ homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 16:183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BD, Dykstra LA. (2006) Interactions between an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist and low-efficacy opioid receptor agonists in assays of schedule-controlled responding and thermal nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318:1300–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BD, Zimmerman EI, Picker MJ, Dykstra LA. (2008) Morphine in combination with metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on schedule-controlled responding and thermal nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324:732–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Negus SS, Mello NK. (1998) Antinociceptive effects of monoamine reuptake inhibitors administered alone or in combination with mu opioid agonists in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 135:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilron I, Jensen TS, Dickenson AH. (2013) Combination pharmacotherapy for management of chronic pain: from bench to bedside. Lancet Neurol 12:1084–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed. National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. (1988) A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 32:77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath RJ, Romero-Sandoval EA, De Leo JA. (2010) Inhibition of microglial P2X4 receptors attenuates morphine tolerance, Iba1, GFAP and mu opioid receptor protein expression while enhancing perivascular microglial ED2. Pain 150:401–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara M, Togo H. (2007) Direct oxidative conversion of aldehydes and alcohols to 2-imidazolines and 2-oxazolines using molecular iodine. Tetrahedron 63:1474–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Kissin I. (2010) The development of new analgesics over the past 50 years: a lack of real breakthrough drugs. Anesth Analg 110:780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Storman EM, Liu NJ, Gintzler AR. (2015) Estrogens Suppress Spinal Endomorphin 2 Release in Female Rats in Phase with the Estrous Cycle. Neuroendocrinology 102:33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza M, Ferrari F, Menghetti I, Tremolada D, Caselli G. (2014) Modulation of imidazoline I2 binding sites by CR4056 relieves postoperative hyperalgesia in male and female rats. Br J Pharmacol 171:3693–3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Aschenbach LC, Chen J, Cassidy MP, Stevens DL, Gabra BH, Selley DE, Dewey WL, Westkaemper RB, Zhang Y. (2009a) Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 6alpha- and 6beta-N-heterocyclic substituted naltrexamine derivatives as mu opioid receptor selective antagonists. J Med Chem 52:1416–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX, Crocker C, Koek W, Rice KC, France CP. (2011a) Effects of serotonin (5-HT)1A and 5-HT2A receptor agonists on schedule-controlled responding in rats: drug combination studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 213:489–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX, Rice KC, France CP. (2009b) Discriminative stimulus effects of 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylphenyl)-2-aminopropane in rhesus monkeys: antagonism and apparent pA2 analyses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328:976–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J-X, Thorn DA, Qiu Y, Peng B-W, Zhang Y. (2014) Antihyperalgesic effects of imidazoline I(2) receptor ligands in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol 171:1580–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX, Zhang Y, Winter JC. (2011b) Morphine-induced antinociception in the rat: supra-additive interactions with imidazoline I₂ receptor ligands. Eur J Pharmacol 669:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DR, France CP. (2014) Impact of efficacy at the μ-opioid receptor on antinociceptive effects of combinations of μ-opioid receptor agonists and cannabinoid receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 351:383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert TF, Vermeirsch HA. (2005) A preclinical comparison between different opioids: antinociceptive versus adverse effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 80:309–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (2013) Pain Management Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools, NIH, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Schrode K, Stevenson GW. (2008) Micro/kappa opioid interactions in rhesus monkeys: implications for analgesia and abuse liability. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16:386–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paronis CA, Bergman J. (1999) Apparent pA2 values of benzodiazepine antagonists and partial agonists in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290:1222–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson LM, Tyacke RJ, Robinson ES, Nutt DJ, Hudson AL. (2007) In vitro and in vivo effect of BU99006 (5-isothiocyanato-2-benzofuranyl-2-imidazoline) on I2 binding in relation to MAO: evidence for two distinct I2 binding sites. Neuropharmacology 52:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham EM, Traynor JR. (2006) Comparison of the antinociceptive response to morphine and morphine-like compounds in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316:1195–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson C, Zhang Y, Del Bello F, Li JX. (2012) Effects of imidazoline I2 receptor ligands on acute nociception in rats. Neuroreport 23:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Blázquez P, Boronat MA, Olmos G, García-Sevilla JA, Garzón J. (2000) Activation of I(2)-imidazoline receptors enhances supraspinal morphine analgesia in mice: a model to detect agonist and antagonist activities at these receptors. Br J Pharmacol 130:146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre M, García-Sevilla JA. (1993) Opposite age-dependent changes of alpha 2A-adrenoceptors and nonadrenoceptor [3H]idazoxan binding sites (I2-imidazoline sites) in the human brain: strong correlation of I2 with monoamine oxidase-B sites. J Neurochem 61:881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HS. (2008) Combination opioid analgesics. Pain Physician 11:201–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorge RE, Mapplebeck JC, Rosen S, Beggs S, Taves S, Alexander JK, Martin LJ, Austin JS, Sotocinal SG, Chen D, et al. (2015) Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat Neurosci 18:1081–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson GW, Folk JE, Linsenmayer DC, Rice KC, Negus SS. (2003) Opioid interactions in rhesus monkeys: effects of delta + mu and delta + kappa agonists on schedule-controlled responding and thermal nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 307:1054–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel EC, Ulibarri CM, Folk JE, Rice KC, Craft RM. (2005) Gonadal hormone modulation of mu, kappa, and delta opioid antinociception in male and female rats. J Pain 6:261–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida R. (2000) The composite additive curve, in Drug synergism and dose-effect data analysis (Tallarida R. ed) 77–89, Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Taves S, Berta T, Liu DL, Gan S, Chen G, Kim YH, Van de Ven T, Laufer S, Ji RR. (2015) Spinal inhibition of p38 MAP kinase reduces inflammatory and neuropathic pain in male but not female mice: sex-dependent microglial signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav Immun DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.006 [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesson F, Limon-Boulez I, Urban P, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Coupry I, Pompon D, Parini A. (1995) Localization of I2-imidazoline binding sites on monoamine oxidases. J Biol Chem 270:9856–9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn DA, Siemian JN, Zhang Y, Li JX. (2015) Anti-hyperalgesic effects of imidazoline I2 receptor ligands in a rat model of inflammatory pain: interactions with oxycodone. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:3309–3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn DA, Zhang Y, Li JX. (2016) Effects of the imidazoline I2 receptor agonist 2-BFI on the development of tolerance to and behavioural/physical dependence on morphine in rats. Br J Pharmacol 173:1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn DA, Zhang Y, Peng BW, Winter JC, Li JX. (2011) Effects of imidazoline I₂ receptor ligands on morphine- and tramadol-induced antinociception in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 670:435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Chen YY, Shang XF, Zhu ZG, Chen GQ, Han Z, Shao B, Yang HM, Xu HQ, Chen JF, et al. (2009) Idazoxan attenuates spinal cord injury by enhanced astrocytic activation and reduced microglial activation in rat experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res 1253:198–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Braithwaite A, Yuan Y, Streicher JM, Bilsky EJ. (2014) Behavioral and cellular pharmacology characterization of 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-(isoquinoline-3′-carboxamido)morphinan (NAQ) as a mu opioid receptor selective ligand. Eur J Pharmacol 736:124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M. (1983) Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 16:109–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]