Abstract

In heart failure (HF), the impaired left ventricular (LV) arterial coupling and diastolic dysfunction present at rest are exacerbated during exercise. C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) is elevated in HF; however, its functional effects are unclear. We tested the hypotheses that CNP with vasodilating, natriuretic, and positive inotropic and lusitropic actions may prevent this abnormal exercise response after HF. We determined the effects of CNP (2 μg/kg plus 0.4 μg/kg per minute, i.v., 20 minutes) on plasma levels of cGMP before and after HF and assessed LV dynamics during exercise in 10 chronically instrumented dogs with pacing-induced HF. Compared with the levels before HF, CNP infusion caused significantly greater increases in cGMP levels after HF. After HF, at rest, CNP administration significantly reduced LV end-systolic pressure (PES), arterial elastance (EA), and end-diastolic pressure. The peak mitral flow (dV/dtmax) was also increased owing to decreased minimum LVP (LVPmin) and the time constant of LV relaxation (τ) (P < 0.05). In addition, LV contractility (EES) was increased. The LV-arterial coupling (EES/EA) was improved. The beneficial effects persisted during exercise. Compared with exercise in HF preparation, treatment with CNP caused significantly less important increases in PES but significantly decreased τ (34.2 vs. 42.6 ms) and minimum left ventricular pressure with further augmented dV/dtmax. Both EES, EES/EA (0.87 vs. 0.32) were increased. LV mechanical efficiency improved from 0.38 to 0.57 (P < 0.05). After HF, exogenous CNP produces arterial vasodilatation and augments LV contraction, relaxation, diastolic filling, and LV arterial coupling, thus improving LV performance at rest and restoring normal exercise responses after HF.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) occurs when the cardiac output is unable to meet the body’s needs without an elevated filling pressure. Thus, exercise intolerance is an important symptomatic manifestation of HF, including HF patients with either reduced or preserved ejection fraction (Dhakal et al., 2015; Little and Borlaug, 2015; Santos et al., 2015). Reduced exercise tolerance is the major cause of disability in HF patients. In fact, it is an independent predictor of hospital readmission and mortality in patients with HF (Francis et al., 2000). Despite enormous advances in the understanding and treatment of HF over the years, it remains a serious and growing health problem, especially in older adults. Current treatment of exercise intolerance in HF patients is unsatisfactory (Kitzman et al., 2010; Braunwald, 2013; Ladage et al., 2013). New therapies to prevent and treat exercise intolerance in HF are urgently needed.

The limitation of exercise tolerance in HF results from both cardiac and peripheral factors. In HF, the exacerbation of diastolic dysfunction during exercise and the resulting increase in left atrial (LA) pressure (P) contribute to exertional dyspnea. Previously, we have shown that in HF the impaired left ventricular (LV) arterial coupling and diastolic dysfunction present at rest are exacerbated during exercise (Cheng et al., 1993; Little et al., 2000). In addition, there is a reversal of the normal exercise-induced augmentation of LV relaxation and a decrease in early diastolic LVP with a resulting increase in LAP. We and others have reported earlier that this abnormal exercise response is attributable to several factors, such as impaired intrinsic contractility, blunted inotropic responses to β-adrenoceptor agonists, enhanced sensitivity of LV relaxation to exercise-induced increased systolic load, high levels of angiotensin II (ANG II) and endothelin-1(Cheng et al., 2001), impaired force-frequency relationship, and a blunted peripheral arterial vasodilator response (Ohte et al., 2003).

Emerging evidence supports C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) as a new therapeutic option for treatment in HF (Lumsden et al., 2010; Del Ry, 2013). It is well known that an important component of cardiovascular homeostasis is provided by the natriuretic peptides (NP). CNP, the third member of the NP family, produced by the endothelium and the heart, exhibits a range of actions. In addition to its well known vasodilating and natriuresis actions, CNP has been described to suppress sympathetic tone and the renin-ANG system (RAS), inhibiting endothelin and vasopressin and improving cardiac β-adrenergic regulation. These properties are beneficial in HF (Levin et al., 1998; Cheng et al., 2001; Corti et al., 2001; Lumsden et al., 2010; Del Ry, 2013). It is evident that CNP can act in both a paracrine and endocrine fashion in many cardiovascular diseases. The biologic actions of CNP are mediated through specific receptors (mainly NPR-B) and the resulting elevation in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Wollert et al., 2003). Importantly, cardiac production of CNP (Kalra et al., 2003) and expression of specific natriuretic peptide receptors, NPR-B are increased in HF (Lumsden et al., 2010), which may alter LV functional response to CNP and suggesting that CNP release may represent a cytoprotective mechanism (Kalra et al., 2003; Del Ry et al., 2008; Lumsden, et al., 2010; Del Ry, 2013). The alterations of CNP-induced cardiac response in HF remain unclearly defined. Specifically, the direct cardiac effects of CNP, independent of the alterations in loading conditions, remain controversial (Pierkes et al., 2002; Wollert et al., 2003; Hobbs et al., 2004; Moltzau et al., 2013, 2014a). Moreover, although inhibiting the degradation of NP or infusing CNP has been suggested as a possible new drug target for the treatment of HF (Lumsden et al., 2010; Del Ry, 2013), no previous studies have examined the exercise response after CNP treatment in HF. Its role and mechanism on exercise performance in HF are unknown.

Accordingly, this study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that CNP may improve both LV systolic and diastolic performance at rest and normalize exercise response in HF. We assessed the acute effect of a clinically relevant dose of CNP (Nakamura et al., 1994) on LV contractility, LV diastolic filling, LV arterial coupling, and mechanical efficiency at rest, and during exercise in a conscious, chronically instrumented dog model with pacing-induced HF (Cheng, et al., 1996, 2001; Bristow, 2000; Little and Borlaug, 2015).

Materials and Methods

Instrumentation

This investigation was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee. All experimental studies conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication 8th ed., update 2011). Fourteen healthy, adult (2–6 years old), heartworm-negative mongrel male dogs (body weight, 25–35 kg) were instrumented to measure three LV internal dimensions, LVP, and LAP. One myocardial lead (model 4312; Cardiac Pacemakers, Minneapolis, MN) was implanted within the myocardium of the right ventricle (RV), and the lead was attached to unipolar multiprogrammable pacemakers (model 8329: Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) positioned under the skin in the chest. Hydraulic occluders were placed around the venae cavae by a technique described previously (Cheng et al., 1993, 1996, 2001; Morimoto et al., 2004).

Data Collection

Studies were performed after full recovery from instrumentation (12 days after original surgery) with the dogs standing and then running on a motorized treadmill (model 1849C, Quinton Inc., Seattle, WA) as previously described (Cheng et al., 1993, 2001).

Experimental Protocol

Two separate experiments were conducted. The first was a pilot dose-response study in subgroups of conscious chronically instrumented normal and HF dogs to determine the optimal dose of exogenous CNP for the main experiment (detailed in Supplemental Material). The second (and main) experiment (n = 10) was performed to examine the functional significance of CNP (2 μg/kg + 0.4 μg/kg per minute, i.v., 20 minutes) in HF.

Preparation and Determination of the Dosing Protocol of CNP

Some previous studies have examined the effects of i.v. administered CNP in many subjects, including humans (Hunt et al., 1994; Pham et al., 1997; Igaki et al., 1998; Guo et al., 2015) and dogs (Morita et al., 1992; Stingo et al., 1992; Clavell et al., 1993). In these studies, variable dosages of CNP were used either by a continuous i.v. infusion (0.01–0.8 μg /kg per minute) or by a bolus injection (0.94 or 5 μg/kg) alone to achieve higher plasma CNP levels in normal anesthetized dogs or in normal humans; however, the past reports were inconsistent. Also, because of the potential for complex effects on myocardial systolic and diastolic function, afterload, and preload, the hemodynamic effects of exogenous infusion of the CNP remain difficult to interpret. No studies have systematically assessed the plasma levels of CNP, peripheral cGMP-generating capacity or myocardial and load-reducing effects of CNP in normal and after HF. The effects on myocardial function and loading conditions of clinically relevant doses of CNP have not been well established.

Thus, to select the effective dosage of CNP for the current project, a dosing selection study was performed in subgroups of normal and HF conscious dogs. In brief, on different days, animals randomly received i.v. infusion of CNP for 20 minutes at doses of 0.1μg/kg per minute or a loading dose of 2 μg/kg first, followed by incremental infusion dose of CNP at 0.1 μg/kg per minute, 0.4 μg/kg per minute, or 1.0 μg/kg per minute, respectively. We compared the effects of these four different dosages of CNP on cardiac function and loading in the animals (see Supplemental Material and Supplemental Table 1 for a detailed description of the pilot dosing selection study and results). Based on the observations from the dosing study on LV P-V relations, blood pressure and VED responses, and target plasma levels of the compounds, we selected the effective dosage of CNP for the main experiment. Based on previous dose-response studies in human and dogs, this regimen determined to be a submaximally effective dose.

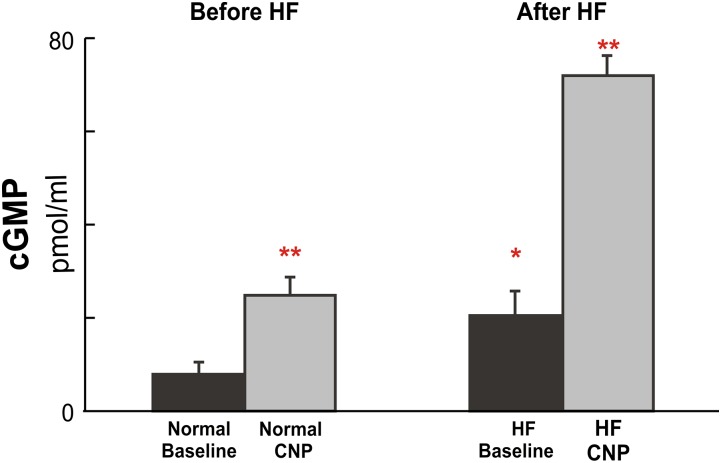

The CNP peptide of 300 μg (human, 22 amino acids; purchased from Bachem Americas, Inc. Torrance, CA) was dissolved in 0.9% saline, sterilized by passage through a 0.2-µm Whatman syringe filter (Buckinghamshire, UK), 2 μg/kg was administered i.v. over 2 minutes, followed by an i.v. infusion of 0.4 μg/kg per minute for 20 minutes. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, CNP dosing profiles demonstrated markedly altered LV functional performance and load-reducing effects. Of note, this dose of CNP produced equally hypotensive action, as we reported previously of ANP (Ohte et al., 1999) and BNP (Igawa et al., 2000) in both normal and HF, but with minimal effects on heart rate. Our current selected dose of CNP also produced comparable plasma levels of cGMP (Fig. 1) and CNP as reported in humans and dogs (Stingo et al., 1992; Clavell et al., 1993; Nakamura et al., 1994; Igaki et al., 1998).

TABLE 1.

Effects of C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) on steady-state hemodynamics at rest and during exercise after heart failure (HF) Values are means ± S.D. (n = 10).

| Before HF | After HF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Control | HF Control | CNP-Treated | |||

| Rest (C) | Rest (A1) | Exercise (A2) | Rest (T1) | Exercise (T2) | |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 108 ± 21 | 139 ± 15 | 172 ± 1* | 141 ± 18 | 162 ± 16* |

| Maximum dP/dt (mm Hg/s) | 2647 ± 293 | 1578 ± 183**** | 2010 ± 214* | 1742 ± 179** | 2954 ± 147 *, *** |

| Minimum dP/dt (mm Hg/s) | −2235 ± 174 | −1547 ± 109**** | −1911 ± 215* | −1718 ± 112** | −2427 ± 203*, *** |

| Stroke Volume (ml) | 14.5 ± 1.3 | 11.5 ± 1.8**** | 12.3 ± 2.4 | 14.3 ± 1.4** | 16.8 ± 1.2 *** |

| LV end-diastolic pressure (mm Hg) | 10.4 ± 2.7 | 41.2 ± 8.5**** | 55.2 ± 8.6* | 36.3 ± 5.3** | 39.2 ± 4.6 *** |

| LV end-systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 109 ± 21 | 104 ± 29 | 111 ± 27 | 93 ± 21** | 105 ± 28 *, *** |

| Minimum LV pressure (mm Hg) | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 23.4 ± 2.8**** | 25.2 ± 2.1 * | 17.8 ± 2.6** | 16.2 ± 2.5 *** |

| Mean LA pressure (mm Hg) | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 28.1 ± 2.4**** | 31.4 ± 2.3 * | 25.3 ± 2.2** | 25.4 ± 2.6 *** |

| LV end-diastolic volume (ml) | 42.0 ± 4.7 | 55.3 ± 5.1**** | 56.1. ± 5.8 | 48.9 ±5.6** | 54.5 ± 3.2 * |

| LV end-systolic volume (ml) | 27.2 ± 4.2 | 42.4 ± 4.2**** | 43.2 ± 4.4 | 35.2 ± 3.3** | 36.4 ± 2.6 *** |

| Maximum dV/dt (ml/s) | 197 ± 19 | 158 ± 24**** | 196 ± 27* | 204 ± 21 ** | 283 ± 25 *, *** |

| Stroke work (mm Hg ⋅ ml) | 1641 ± 159 | 1043 ± 260**** | 1354 ± 215* | 1460 ± 267** | 1972 ± 221 *, *** |

| Cardiac output (ml/min) | 1671 ± 210 | 1477 ± 162**** | 2063 ± 18 * | 1648 ± 143** | 2798 ± 215*, *** |

| EA (mm Hg/ml) | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 11.7 ± 1.3**** | 12.1 ± 1.2 | 8.4 ± 1.4** | 7.5 ± 0.6*** |

| Time constant of relaxation (ms) | 24.2 ± 1.3 | 39.3 ± 2.6**** | 42.6 ± 2.8* | 35.4 ± 2.3** | 34.2 ± 2.4*** |

dP/dt, rate of rise of LV pressure; dV/dt, peak rate of mitral flow; EA, arterial elastance; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular.

P < 0.05 HF exercise (A2) versus HF rest (A1).

P < 0.05 HF CNP rest (T1) versus HF control rest (A1).

P < 0.05 HF CNP exercise (T2) versus HF control exercise (A2).

P < 0.05 HF control rest (A1) versus normal control rest (C).

TABLE 2.

Effects of C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) on pressure-volume relations at rest and during exercise after heart failure (HF) Values are means ± S.E. (n = 10).

| Before HF | After HF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Control | HF Control | CNP-Treated | |||

| Rest | Rest | Exercise | Rest | Exercise | |

| EES (mm Hg/ml) | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 0.3**** | 3.9 ± 0.2* | 5.6 ± 0.3** | 6.4 ± 0. 3 *, *** |

| EES/EA | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.04**** | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.06** | 0.87 ± 0.08 *, *** |

| MSW (mm Hg) | 89.7 ± 5.3 | 60.2 ± 3.6**** | 52.5 ± 3.3* | 68.5 ± 3.1** | 79.7 ± 2.6 *, *** |

| SW/PVA | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.04**** | 0.38 ± 0.03* | 0.51 ± 0.02** | 0.57 ± 0.02 *, *** |

EES, slope of linear PES-VES relation; MSW, slope of SW-VED relation; PVA, LV pressure-volume area; SW, stroke work.

P < 0.05, HF exercise versus HF rest.

P < 0.05, CNP rest versus HF control rest.

P < 0.05, HF CNP exercise versus HF control exercise.

P < 0.05 HF control rest versus normal control rest.

Fig. 1.

Group mean data (means ± S.D.) (n = 10/group) of the effects of c-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) administration on plasma levels of cGMP at rest before and after HF. The resting values of cGMP were significantly elevated after the development of HF; after CNP administration, values were further increased to very high levels both before and after HF. *P < 0.05, HF baseline versus normal baseline; **P < 0.05, CNP versus corresponding baselines.

Functional Significance of CNP in HF

Normal Rest and Induction of HF.

Studies were performed after the animals had fully recovered from instrumentation. First, the normal rest baseline studies were performed as previously described (Cheng et al., 1993). After completion of baseline studies, rapid RV pacing (at 220–240 beats/min) was initiated using the pacing protocol to induce HF. After 4–5 weeks of rapid pacing, when the LV PED, during the nonpacing period, had increased by more than 15 mm Hg over the prepacing control level, we obtained HF data.

Effect of Exercise after HF without and with CNP.

During the stable HF period, we examined the cardiac response to exercise before and after CNP administration. Briefly, before each study, the pacemaker was turned off and the dog was allowed to equilibrate for at least 40 minutes. Then, steady-state measurements were obtained at rest while the dogs stood on a motorized treadmill (model 1849C; Quinton; Seattle, WA) (Cheng et al., 1993, 2001).Variably loaded LV P-V loops were generated by transient occlusion of the venae cavae (VCO), as previously described. The first HF exercise was then performed with the dogs running on the treadmill.

The treadmill speed was gradually increased every 1 to 2 minutes from 2.5 mph up to the maximum tolerated level (4.5–6 mph). The animals exercised at this level until they could no longer keep up with the treadmill. At submaximal levels of exercise, both steady-state and VCO data were obtained, and then the treadmill was suddenly stopped. Data were acquired during 12- to 15-second periods throughout the exercise protocol. We analyzed the data recorded during submaximal level of exercise to avoid marked fluctuation by respiration. The total exercise time ranged from 4.5 to 8 minutes.

After dogs rested for 40 minutes, CNP was administered i.v. with a loading dose of 2μg/kg followed by infusion of CNP 0.4 μg/kg per minute for 20 minutes. Ten minutes after CNP treatment, when the arterial pressure reached a stable level, steady-state hemodynamic data and caval occlusion data were collected with the subjects at rest. Then the treadmill exercise protocol was again performed and data were collected at submaximal levels of exercise. We previously observed that there is no difference in the response to exercise repeated after a 40-minute rest period (Cheng et al., 1993, 2001). The values of resting controls were also similar before initial exercise and with a 40-minute resting period after exercise.

Data Processing and Analysis.

As previously described, LV volume, LV end-systolic pressure (LVPES)-end-systolic volume (VES) relation and its slope (EES), and stroke work (SW)-end-diastolic volume (VED) relation and its slope (MSW) were analyzed (Cheng et al., 1996, 2001). Relaxation was evaluated by determining the time constant of the isovolumic decrease of LVP (τ). LVP from the time of peak −dP/dt until mitral valve opening was fit to the exponential equation LVP = PA exp (−t/τ) + PB, where t is time and PA, PB, and τ are constants determined by the data. Although the decrease in isovolumic P is not exactly exponential, the time constant, which is derived from the exponential approximation, provides an index of the rate of LV relaxation (Gilbert and Glantz, 1989; Miyazaki et al., 1990). In addition, τ was also calculated by the Weiss method (monoexponential decay model to zero asymptote). LV-arterial coupling was quantitated as the ratio of EES to EA, determined as PES/stroke volume (SV). The LV P-V area (PVA), which represents the total mechanical energy, was determined as the area under the PES-VES relation and systolic P-V trajectory above the PED-VED curve. The efficiency of the conversion of mechanical energy to external work of the heart was calculated as SW/PVA (Suga et al., 1979; Little and Cheng, 1993; Ohte et al., 2003; Masutani and Senzaki, 2011). Data acquisition and analysis were not blinded to group identity CNP treatment owing to the study design.

Determination of Plasma CNP and cGMP Concentrations.

To determine the effects of CNP on plasma levels of cGMP before and after HF, venous blood samples were collected in the animals at rest before HF before and after CNP infusion. Then blood samples were obtained again after HF before and after CNP in these same animals. To further assess whether HF alters plasma levels of CNP, in the subgroups of animals, blood samples were collected (into ice-chilled EDTA tubes containing aprotinin and processed) for CNP measurements in normal and HF animals at baseline and after CNP administration. Plasma CNP and cGMP concentrations were determined with the specific commercial radioimmunoassay (RIA) of CNP RIA kit and cyclic GMP RIA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Belmont, CA) as previously described (Bruun et al., 1989; Clavell et al., 1993; Brandt et al., 1997; Igaki et al., 1998; Del Ry et al., 2005) by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Hypertension Core Laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were made with Student’s t test for paired observations and ANOVA with the Bonferroni method of multiple paired comparisons as appropriate. Significance was established as P < 0.05. Data for steady state are expressed as means ± S.D.; values for LV P-V relations are expressed as means ± S.E.

Postmortem Evaluation

At the conclusion of the studies, the animals were killed by lethal injection of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg, i.v.), and the hearts were examined to confirm that instrumentation was properly positioned.

Results

The data from the main experiment in response to the selected submaximally effective dose of CNP (2 μg/kg loading plus 0.4 μg/kg per minute of infusion) are reported in the following sections of this article. The additional pilot dosing study is presented in Supplemental Table 1. Four different dosages of CNP showed dose-related elevations of plasma levels of CNP and reduced PES but showed increased EES without significant changes in the heart rate in both normal and HF.

Increased Plasma Levels of cGMP and CNP after CNP Administration: Normal Versus HF.

As exhibited in Fig. 1, at rest, plasma levels of cGMP were significantly elevated in HF compared with levels observed before HF induction. Both before and after HF induction, CNP infusion caused similar (about 2.5-fold) increases in plasma cGMP levels (before HF: 7.2–24.7 pmol/ml; after: 20.2 to 71.6 pmol/ml); however, in response to the same dose of CNP administration, the absolute increases of cGMP concentrations from baselines were significantly greater in HF (∼3-fold higher) than that occurring before HF (Δ cGMP = 51.4 vs. 17.5 pmol/ml), suggesting an enhanced response in HF. In the subgroup animals, compared with normal, after HF, not only the basal concentrations of circulating CNP were significantly higher, but the same dose of CNP administration also caused greater increases in plasma levels of CNP (normal: 1132.6 vs. 4.8 pg/ml; HF: 1984.8 vs. 19.6 pg/ml) (Supplemental Table 1).

Abnormal Hemodynamic Responses in Pacing-Induced HF: Rest Versus Exercise.

While the subjects were at rest, consistent with our past reports (Cheng et al., 2001), chronic RV rapid pacing in a canine model produced progressive LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction. As summarized in Tables 1 and 2, compared with normal rest, LVPED, VED, VES, and EA significantly increased, whereas dP/dtmax, −dP/dtmin, SV, stroke work, and cardiac output all significantly decreased. LV systolic dysfunction was shown by significant reduced EES and MSW (Table 2) with reduced LV dP/dtmax. LV diastolic dysfunction was indicated by significantly decreased maximum dV/dt (dV/dtmax) with elevated LVPmin, LVPED, and mean LAP, as well as prolonged LV relaxation with increased time constant of LV relaxation (τ).

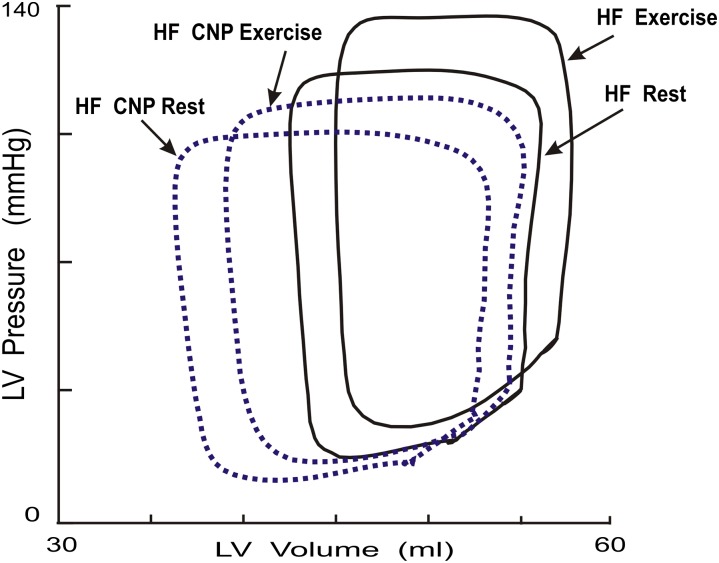

During exercise, as typically displayed in Figs. 2–4, such abnormalities at rest were exacerbated. Compared with HF at rest, during exercise, the heart rate, LVPES, τ (HF exercise 42.6 vs. HF rest 39.3 ms), LVPED, LVPmin (25.2 vs. 23.4 mm Hg) and mean LAP (31.4 vs. 28.1 mm Hg) all significantly increased (Fig. 2; Table 1). These changes were accompanied by a consistent rightward and upward shift of the early diastolic portion of the LV P-V loop (Fig. 2). During early diastole, at an equivalent LV volume, the LVP was significantly higher during exercise than at rest after HF. Compared with the HF preparation at rest, during exercise, LV contractile performance was further impaired as indicated by markedly rightward shifts with significant decreases in the slopes of LV PES-VES relation (EES) (3.9 vs. 4.4 mm Hg/ml) and LV SW-VED relation (MSW) (52.5 vs. 60.2 mm Hg) (Fig. 2; Table 2). In addition, the impaired LV arterial coupling present at rest was exacerbated during HF exercise. Compared with HF at rest, HF exercise caused a significant decrease in EES, whereas EA was relatively unchanged, resulting in decreased EES/EA ratio (0.32 vs. 0.38) with reduced SW/PVA (0.38 vs. 0.43) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Examples of the effects of CNP on LV diastolic filling during exercise after HF. The steady-state LV P-V loops obtained from one animal after HF at rest and during exercise with and without the treatment of CNP. Each loop was generated by averaging the data obtained during a 12- to 15-second recording period, spanning several respiratory cycles. After HF, the early diastolic portion of LV P-V loop was shifted upward during exercise so that the early diastolic LVP was increased during exercise after HF. After treatment with CNP, exercise produced a greater stroke volume and the abnormal exercise response was restored to the normal downward shift during exercise so that early diastolic LVP did not increase, but it decreased with exercise after HF.

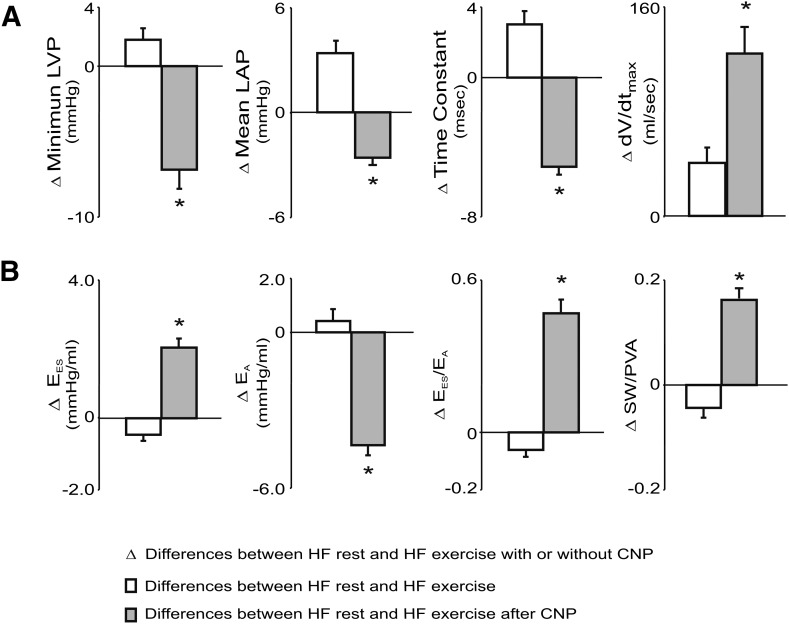

Fig. 4.

Group mean data on the differences between HF at rest and HF exercise with and without treatment of CNP on LV filling, LV arterial coupling, and stroke work (SW)/P-V area (PVA) (SW/PVA). Compared with HF at rest, HF exercise caused an increase in dV/dtmax owing to significant increases in mean LAP, whereas τ and LVPmin were also significantly increased. In contrast, during HF exercise with treatment of CNP, there was a greater increase in dV/dtmax with decreases in τ and mean LAP. During HF exercise, EES/EA decreased, resulting from a significantly increased EA, but decreased EES, which led to a reduction in SW/PVA. In contrast, CNP reversed the HF exercise-induced abnormal responses and caused significant increases in EES, EES/EA, and SW/PVA during HF exercise. *P < 0.05, HF exercise with CNP versus HF exercise.

CNP Improves Hemodynamic Responses in Pacing-Induced HF: Rest Versus Exercise.

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4, compared with HF at rest, CNP produced no change in heart rate but significantly reduced PES (CNP: 93 vs. baseline:104 mm Hg), arterial elastance (EA, 8.4 vs. 11.7 mm Hg/ml) and PED (36.3 vs. 41.2 mm Hg) (P < 0.05). The peak mitral flow (dV/dtmax, 204 vs. 158 ml/s) was also increased due to decreased minimum LVP (LVPmin, 17.8 vs. 23.4 mm Hg) and τ (35.4 vs. 39.3 ms) (P < 0.05).

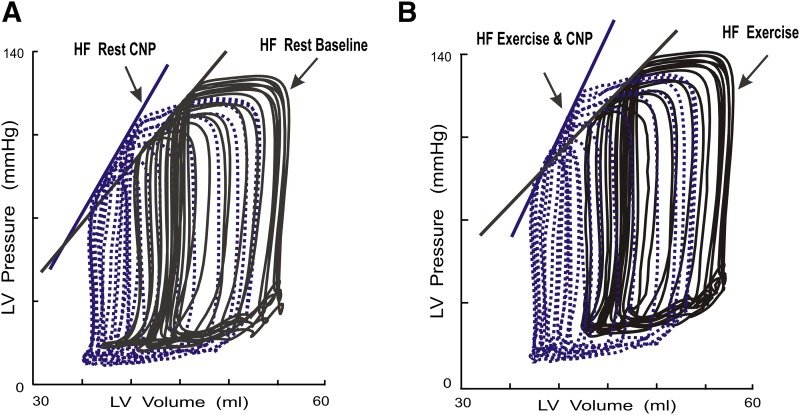

Importantly, as presented in Table 2 and exhibited in Figs. 3A, compared with HF preparations at rest, CNP caused leftward shifts and increased slopes of P-V relations of EES (5.6 vs. 4.4 mm Hg/ml) and MSW (68.5 vs. 60.2 mm Hg). This indicates that in conscious dogs after HF, CNP produces a direct positive inotropic effect on LV contractile performance. The LV-arterial coupling, quantified as EES/EA, was improved 68% (0.64 vs. 0.38) (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Examples of the effects of CNP on LV PES-VES relations during exercise after HF. LV P-V loops and P-V relations determined from a conscious dog after HF before and after administration of CNP. Treatment with CNP produced leftward shifts of the LV PES-VES with increased slopes, which indicates that CNP increased LV contractility after HF. LV P-V loops recorded after transient caval occlusions in one conscious dog after HF at rest before and after CNP (A) and during exercise before and after CNP (B). After HF, compared with rest, exercise caused a decrease in the slope of the LV PES-VES relation, EES. Compared with HF exercise without treatment, HF exercise after treatment with CNP produced marked leftward shifts of the LV PES-VES relation with increase in the slope of EES, indicating that CNP increased LV contractility after HF both at rest and during exercise.

During exercise after HF, treatment with CNP prevented HF exercise-induced adverse effects on LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction. As shown in Table 1 and displayed in Figs. 2 and 3, compared with exercise in HF preparations, exercise after CNP treatment significantly attenuated exercise-induced increase in PES, reversed exercise-induced abnormal increases in LVPED and mean LAP, reversed exercise-induced abnormal increases in LVPmin,τ, and upward shift of the early diastolic portion of LV P-V loop, and further augmented dV/dtmax. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the group means data on the differences between HF at rest and HF exercise with and without treatment of CNP clearly revealed that this is the opposite of the response to exercise after HF. For example, compared with HF rest, HF exercise significantly increased τ (Δ τ = 3.3 ms, HF exercise: 42.6 vs. HF rest: 39.3 ms), LVPmin, (ΔP = 1.8 mm Hg, 25.2 vs. 23.4 mm Hg), and mean LAP (ΔP = 3.3 mm Hg: 31.4 vs. 28.1 mm Hg). By contrast, compared with HF rest, CNP HF exercise significantly decreased τ (Δ τ = −5.1 ms, CNP HF exercise: 34.2 vs. HF rest: 39.3 ms), LVPmin, (ΔP = −7.1 mm Hg: 16.3 vs. 23.4 mm Hg) and mean LAP (ΔP = −2.7 mm Hg, 25.4 vs. 28.1 mm Hg). Thus, in HF exercise, the increased dV/dtmax is due mainly to significantly increased mean LAP, whereas in CNP HF exercise, the increased dV/dtmax is attributed to the enhancement of LV relaxation with a decrease in early diastolic LV pressure.

As demonstrated in Fig. 3B, compared with HF exercise, CNP caused leftward shifts of PES-VES relations with increased EES and MSW during exercise. In addition, during HF exercise with CNP treatment, there was a reversal of abnormal HF exercise response in ventricular-vascular coupling and cardiac mechanical efficiency. During HF exercise after treatment with CNP, HF exercise-caused decreases in EES and EES/EA were reversed to increases in EES (6.4 vs. 3.9 mm Hg/ml) and EES/EA. Thus, treatment with CNP further improved HF exercise SW/PVA by 50%, from (0.38–0.57) (Fig. 4; Table 2). The duration of exercise was also significantly increased (7.8 vs. 5.4 minutes).

Discussion

Exercise intolerance, a hallmark of HF, remains a serious and growing health problem. Currently, no satisfactory therapeutic interventions are available for exercise intolerance in HF patients (Kitzman et al., 2010; Braunwald, 2013; Ladage et al., 2013; Dhakal et al., 2015; Little and Borlaug, 2015; Santos et al., 2015). Aldosterone antagonism, angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibitor therapy and β-blockade treatment improves survival in patients with HF but has failed to improve exercise capacity in recent clinical trials (Narang et al., 1996; Jorde et al., 2008; Kociol, 2012; Conraads et al., 2013; Ladage et al., 2013). In fact, there has been a dearth of new developments in HF therapies in the last decade, with the exception of the recently described angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor of LCZ696, which prevents NP degradation while concomitantly blocking ANG1 receptor; however, its cardiovascular outcomes in HF at rest and during exercise remains to be investigated (Langenickel and Dole, 2012; Singh and Lang, 2015; Owens et al., 2016).

In the current investigation, we showed, for the first time, that administration of CNP in a canine model of HF that mimics many features of clinical HF (Cheng et al., 1993, 2001; Spinale et al., 1997; Bristow, 2000) prevented the abnormal response to exercise in HF, including improved LV diastolic filling, increased LV contractility, and decreased arterial elastance with an overall improvement in LV-arterial coupling and mechanic efficiency. This effect of CNP is more effective than what we observed previously in the exercise canine HF model by using ANG II AT1 blockade or ET-1 antagonist alone (Cheng et al., 2001).

How does CNP administration prevent exercise-induced exacerbation of LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction and restore normal exercise response in HF? The beneficial effects of CNP we observed in the current study mainly result from reduction in the systolic load and the positive inotropic effect of CNP. The reduction in the systolic load at rest and during exercise in HF is due to the vasodilator effect of CNP, which is mainly attributed to natriuretic peptide effects on cGMP to an activation of a particulate guanylyl cyclase (Wright, et al., 1996). CNP activates the Natriuretic peptide receptor-B (NPR-B) receptor to stimulate the production and release of cGMP (Lumsden et al., 2010; Kuhn, 2015; Pagel-Langenickel et al., 2007). CNP is also able to induce vasorelaxation by hyperpolarization (Barton et al., 1998). In addition, suppression of ANG II and endothelin-1 by CNP also importantly contributes its systolic load reduction at rest and during exercise in HF.

The mechanism on the positive inotropic action of CNP is not entirely clear. In fact, CNP has been reported variably to have a positive inotropic effect (Hirose, et al., 1998; Wollert et al., 2003; Pagel-Langenickel et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2009), a negative inotropic effect (Qvigstad et al., 2010; Moltzau et al., 2013, 2014a), or biphasic (Pagel-Langenickel et al., 2007) inotropic effects on LV contractile performance. These disparate observations may be due to the confounding effects of anesthesia, open-chest surgery, tissue preparations, loading conditions, species differences, and the dosages of CNP used. Indeed, although variable dosages of CNP were used in different dose-response studies, the effects on myocardial function and loading conditions of clinically effective doses of CNP have not been well established. More precise contractility assessments have not been performed, and CNP’s integrated effects on LV contractility, independent of the alterations in loading conditions, both at rest and during exercise in HF, are not known. It remains unclear whether cGMP-generating capacity or myocardial and load-reducing effects of exogenous CNP are qualitatively or quantitatively altered in HF. Although recent studies have suggested the efficiency of exogenous CNP in the treatment of HF, only limited data exist to establish the superiority of CNP over the other NP. It is important to understand these effects, especially if increasing CNP is to be used as a therapeutic strategy for patients with HF.

To address these limitations, in reference to available past dose-response studies in dogs (Morita et al., 1992; Stingo et al., 1992; Clavell et al., 1993; Pagel-Langenickel et al., 2007) and humans (Hunt et al., 1994; Pham et al., 1997; Igaki et al., 1998; Guo et al., 2015), we performed a dose-response study. For the first time, we combined both a bolus injection and continuous i.v. infusion of CNP and established effective and stable pharmacologic plasma concentrations of CNP. We simultaneously assessed cardiovascular functional performance and plasma levels of CNP and cGMP and selected the submaximally effective dose of CNP for the current study.

In the current study, we evaluated LV contractile performance after the effective dose of CNP in conscious HF dogs with pressure-volume analysis, a load-independent measure of LV contractility, as previously described (Little and Cheng, 1993; Cheng et al., 1996). Compared with HF preparation, we found that CNP caused significant increases in EES and MSW (the load insensitive index of contractility) both at rest and during exercise, demonstrating positive inotropic effects of CNP in HF. These observations are supported with the findings from previous studies suggesting CNP stimulation produced positive inotropic responses may due to the direct myocardial effects (Hirose, et al., 1998; Wollert et al., 2003).

In contrast to the cardiac response to ANP and BNP, CNP produced an enhanced positive inotropic effect in HF as observed by us (Ohte et al., 1999; Igawa et al., 2000) and by others (McCall and Fried, 1990; Moe et al., 1990; Tsutamoto et al., 1997; Nakamura et al., 1998; Tajima et al., 1998). Previously, we have reported that ANP has negative effects on LV contractility and relaxation (Ohte, et al., 1999), whereas BNP has no direct cardiac inotropic action both before and after HF.

Specifically, in our past studies, we first assessed the effect of similar i.v. dosages of ANP (2 μg/kg loading dose plus 0.1 μg/kg per minute of infusion for 15 minutes) on LV systolic and diastolic performance before and after HF at rest. In addition, data were collected with higher infusion rates of ANP (0.5 and 1.0 μg/kg per minute). We found that ANP produced arterial vasodilation with significantly decreased LV PES (−9 to −10 mm Hg) and a load-independent depression of LV contractile function (with about 9% reductions of EES and MSW) and slowed relaxation both before and after HF. Importantly, the vasodilatory and cardiodepressant effects of ANP were not attenuated in HF; however, the contractile depression and slowing of relaxation after HF are more than offset by ANP’s arterial vasodilation so that steady-state SV, relaxation, and early diastolic function are enhanced. In another series of experiments, we assessed the functional effects of clinically relevant doses of nesiritide (generic name of human BNP, 2 μg/kg plus 0.04 μg/kg per minute, iv. 20 minutes) in the same canine model with pacing-induced HF at rest and during exercise (Igawa et al., 2000). We found that after HF, at matched levels of exercise, treatment with BNP prevented exercise-induced increases in PES, mean LAP, and LVPmin. With BNP, there were no significant changes in EES, but EES/EA was improved owing to a decrease in EA. τ was much shortened, and peak mitral flow was further augmented. In contrast, during HF exercise, equal hypotensive CNP was more effective than BNP, producing decreases in LV Pmin, VES, and τ. Exercise duration in HF was increased only by CNP.

In agreement with the observed positive inotropic effect of CNP in HF in the canine model, we also observed positive CNP-induced modulation on LV and myocyte functional performance in both normal and HF rats. In rats with HF, CNP caused greater improvement of intact LV and myocyte contraction and relaxation with further augmentation of increased [Ca2+]i transient and L-type Ca2+ current (Zhou et al., 2009). The enhanced CNP positive modulation on cardiac performance in HF we observed might be due to the fact that the cardiac expression of NPR-B are increased in HF. Additionally, it has been shown that the activity of CNP is enhanced in the absence of endogenous nitrous oxide (NO) production, indicating that CNP may play a compensatory role in protecting the heart and vasculature when NO signaling is impaired (NO signaling dysfunction is characteristic of HF) (Lumsden et al., 2010).

Compared with normal hearts, after HF, not only the basal concentrations of circulating CNP were significantly higher, but the same dose of CNP administration also caused greater increases in plasma levels of CNP. Clinical pharmacokinetic studies in HF reported that the main changes in drug pharmacokinetics seen in HF are a reduction in the volume of distribution and impairment of clearance (Shammas and Dickstein, 1988). It is likely that factors contribute to this alteration may be involved in reduced metabolism of CNP or reduced volume of distribution in HF (Shammas and Dickstein, 1988). This new finding is consistent with the observations made in HF patients (Del Ry et al., 2005). It has been demonstrated that the plasma level of CNP in healthy subjects was 2.7 pg/ml and significantly increased in HF as a function of clinical severity to 7.0 pg/ml, 9.6 pg/ml, and 11.8 pg/ml in New York Heart Association class II, III, and IV patients, respectively.

Past studies have reported that the baseline plasma cGMP concentration was higher in the HF patients, but further increases in plasma cGMP in response to ANP were limited (Moe et al., 1992). In our conscious dogs, compared with baselines, BNP administration produced similar increases in plasma cGMP levels both before (135 vs. 13 pmol/ml) and after HF (167 vs. 23 pmol/ml) (Igawa et al., 2000). As opposed to ANP and BNP, in the current study, the ability of CNP to generate the second-messenger cGMP in HF was enhanced. Compared with before HF, CNP caused significant increases of plasma levels of cGMP after HF, although we could not determine myocardial levels of cGMP. The cGMP signaling plays an important role that counters a broad array of acute and chronic cardiac stress responses, including those from β-adrenergic stimulation, ischemic injury, and pressure and volume overload (Kass, 2012). CNP has been reported to exert marked cGMP-mediated positive inotropic and lusitropic effects (Lumsden et al., 2010). The cGMP generated by NPR-B has been reported to increase β1-adrenoceptor-mediated positive inotropic responses through inhibition of PDE3 (Moltzau et al., 2013). In HF, it is possible that cGMP may affect cAMP signaling via cross-talk regulation by cGMP-regulated subtypes of PDEs (PDE2 or PDE3) (Takimoto, 2012; Moltzau et al., 2014b), which leads to an increase in intracellular cAMP and increased contractility; however, whether and to what extent administration of CNP affects the cGMP-cAMP pathway, improving β-adrenergic stimulation and thereby contributing to the beneficial action of CNP in HF, is unknown.

Of equal importance, CNP has been viewed as endogenous inhibitor of RAS and endothelin (Sherwood et al., 2011). Previously, we have reported that in HF, ANG II, and endothelin-1 produce direct depressions in intact LV contraction and exacerbate myocyte contractile dysfunction (Cheng et al., 1996; Suzuki et al., 1998). We further demonstrated that in HF, circulating ANG II and endothelin-1 increase to very high levels during exercise and exacerbate the diastolic dysfunction present at rest. Thus, inhibiting ANG II and endothelin-1 may also contribute to the increased LV contractility, relaxation, and improved LV diastolic filling at rest and during exercise after CNP administration (Cheng et al., 2001).

Previous observations in our laboratory have demonstrated that normally functioning LV and arterial systems are nearly optimally coupled to produce stroke work (SW) both at rest and during exercise (Little and Cheng, 1993). In the current study, we found that during the development of HF, the EES/EA ratio was reduced, resulting in less than maximal SW. Furthermore, this coupling ratio was further depressed during exercise, thus contributing to exercise intolerance in HF. Treatment with CNP significantly increased the EES/EA ratio with resulting near maximum SW both at rest and during exercise after HF. Thus, with CNP, LV mechanical efficiency was significantly augmented in HF both at rest and during exercise. This finding may be consistent with recent views that NP has emerged as a key regulator of energy use and metabolism, promoting lipolysis, lipid oxidation, and mitochondrial respiration (Kuhn, 2015).

The upward shift in the early diastolic portion of the LV P-V loop that we observed during HF exercise is similar to that reported by Miyazaki and colleagues (1990) in exercising dogs with coronary stenosis as well as that found in clinical studies of exercise-induced ischemia (Tebbe et al., 1987). In these studies, the decrease in LV distensibility during exercise was due to the effect of myocardial ischemia. Although our animals did not have coronary stenosis, exercise-induced ischemia may have contributed to our findings. Thus, CNP caused coronary vasodilatation (Hobbs et al., 2004), which may have contributed to improved LV relaxation and LV filling during exercise after HF.

Study Limitations

Several issues should be considered in the interpretation of our data. First, our observations were obtained from a pacing-induced HF canine model. The conscious dog model is a useful model to assess drug efficacy and safety, and rapid pacing produces an animal model of HF that closely mimics that of clinical congestive cardiomyopathy in humans, including biventricular chamber dilatation with increased LV and RV filling pressures and striking abnormalities in systolic and diastolic function (Cheng, et al., 1996; Spinale et al., 1997; Bristow, 2000; Little and Borlaug, 2015). We cannot be certain, however, that these results are applicable to HF from other causes, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Second, we studied the acute effects of CNP treatment. We do not know the effects of prolonged treatment with CNP. Third, we did not examine the effects of CNP on LV end-diastolic pressure–volume relation during exercise in this investigation. Further studies are needed to focus on this point in HF. Fourth, we measured the plasma levels of cGMP, but we did not measure the cGMP or cAMP levels in the heart. It is possible that its beneficial actions are attributable to the alteration on β-adrenergic stimulation activated by subtype PDEs that regulated the CNP-activated cGMP/protein kinase G (PKG) pathway (Moltzau et al., 2013, 2014b). Finally, the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor of LCZ696 has demonstrated greater efficacy than enalapril in a phase 3 trial in HF with reduced ejection fraction (Langenickel and Dole, 2012; Singh and Lang, 2015). We speculate that its ability to augment the endogenous CNP may play a major role in its greater efficacy in HF. Clearly, more insight will be gained from our ongoing work designed to assess the influence of LCZ696 on endogenous CNP levels, as well as on cardiac performance at rest and during exercise in our canine HF model.

In conclusion, in dogs with pacing-induced HF, the generation of cGMP in response to CNP is not blunted. A clinically relevant dose of CNP produces arterial vasodilatation and augments LV contraction, relaxation, diastolic filling, LV arterial coupling, and mechanical efficiency, thus improving LV performance both at rest and during exercise. This study is important in that it supports the view that HF is a state of functional natriuretic peptide hormone deficiency (Kuhn, 2015), illuminates a new potential mechanism of exercise intolerance in HF, and points to a new molecular target for this serious and increasing health problem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ping Tan for computer programming, Xiaowei Zhang for technical assistance, Stacey Belton for administrative support, and Bridget Brosnihan for performing the biochemical CNP analyses.

Abbreviations

- ANG

angiotensin

- CNP

C-type natriuretic peptide

- dV/dtmax

peak mitral flow

- EA

arterial elastance

- EES

LV contractility

- HF

heart failure

- LA

left atrial

- LV

left ventricular

- LVP

left ventricular pressure

- NPR-B

Natriuretic peptide receptor-B

- PES

end-systolic pressure

- SV

stroke volume

- SW

stroke work

- VCO

vena cava occlusion

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: T. Li, C. P. Cheng.

Conducted experiments: H. J. Cheng, Ohte, Hasegawa, Morimoto, C. P. Cheng.

Performed data analysis: T. Li, Ohte, Hasegawa, Morimoto, C. P. Cheng.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: T. Li, Herrington, Little, W. Li, C. P. Cheng.

Footnotes

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant AG049770 to H.J.C.); the NIH (Grant HL074318), American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (Grant 11GRNT7240020) (to C.P.C.); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81270252) (to W.M.L.).

This work was previously presented as an abstract at the American Heart Association Meeting in 2014 and published as Che Ping Cheng, Hiroshi Hasegawa; Atsushi Morimoto; Heng-Jie Cheng; William C. Little. (2014) C-type natriuretic peptide improves left ventricular systolic and diastolic functional performance at rest and during exercise after heart failure. Circulation 130:A12583.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

Deceased. We would like to dedicate this article to the memory of Dr. Little (May 1, 1950–July 9, 2015).

References

- Barton M, Bény JL, d’Uscio LV, Wyss T, Noll G, Lüscher TF. (1998) Endothelium-independent relaxation and hyperpolarization to C-type natriuretic peptide in porcine coronary arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 31:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt RR, Mattingly MT, Clavell AL, Barclay PL, Burnett JC., Jr (1997) Neutral endopeptidase regulates C-type natriuretic peptide metabolism but does not potentiate its bioactivity in vivo. Hypertension 30:184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E. (2013) Research advances in heart failure: a compendium. Circ Res 113:633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR. (2000) Beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in chronic heart failure. Circulation 101:558–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruun NE, Nielsen MD, Skøtt P, Giese J, Leth A, Schütten HJ, Rasmussen S. (1989) Changed cyclic guanosine monophosphate atrial natriuretic factor relationship in hypertensive man. J Hypertens 7:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CP, Noda T, Nozawa T, Little WC. (1993) Effect of heart failure on the mechanism of exercise-induced augmentation of mitral valve flow. Circ Res 72:795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CP, Suzuki M, Ohte N, Ohno M, Wang ZM, Little WC. (1996) Altered ventricular and myocyte response to angiotensin II in pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res 78:880–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CP, Ukai T, Onishi K, Ohte N, Suzuki M, Zhang ZS, Cheng HJ, Tachibana H, Igawa A, Little WC. (2001) The role of ANG II and endothelin-1 in exercise-induced diastolic dysfunction in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280:H1853–H1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavell AL, Stingo AJ, Wei CM, Heublein DM, Burnett JC., Jr (1993) C-type natriuretic peptide: a selective cardiovascular peptide. Am J Physiol 264:R290–R295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conraads VM, Van Craenenbroeck EM, De Maeyer C, Van Berendoncks AM, Beckers PJ, Vrints CJ. (2013) Unraveling new mechanisms of exercise intolerance in chronic heart failure: role of exercise training. Heart Fail Rev 18:65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti R, Burnett JC, Jr, Rouleau JL, Ruschitzka F, Lüscher TF. (2001) Vasopeptidase inhibitors: a new therapeutic concept in cardiovascular disease? Circulation 104:1856–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ry S. (2013) C-type natriuretic peptide: a new cardiac mediator. Peptides 40:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ry S, Cabiati M, Lionetti V, Emdin M, Recchia FA, Giannessi D. (2008) Expression of C-type natriuretic peptide and of its receptor NPR-B in normal and failing heart. Peptides 29:2208–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ry S, Passino C, Maltinti M, Emdin M, Giannessi D. (2005) C-type natriuretic peptide plasma levels increase in patients with chronic heart failure as a function of clinical severity. Eur J Heart Fail 7:1145–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal BP, Malhotra R, Murphy RM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Baggish AL, Weiner RB, Houstis NE, Eisman AS, Hough SS, Lewis GD. (2015) Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the role of abnormal peripheral oxygen extraction. Circ Heart Fail 8:286–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DP, Shamim W, Davies LC, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Coats AJ. (2000) Cardiopulmonary exercise testing for prognosis in chronic heart failure: continuous and independent prognostic value from VE/VCO(2)slope and peak VO(2). Eur Heart J 21:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JC, Glantz SA. (1989) Determinants of left ventricular filling and of the diastolic pressure-volume relation. Circ Res 64:827–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Goetze JP, Jeppesen JL, Burnett JC, Olesen J, Jansen-Olesen I, Ashina M. (2015) Effect of natriuretic peptides on cerebral artery blood flow in healthy volunteers. Peptides 74:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose M, Furukawa Y, Kurogouchi F, Nakajima K, Miyashita Y, Chiba S. (1998) C-type natriuretic peptide increases myocardial contractility and sinus rate mediated by guanylyl cyclase-linked natriuretic peptide receptors in isolated, blood-perfused dog heart preparations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs A, Foster P, Prescott C, Scotland R, Ahluwalia A. (2004) Natriuretic peptide receptor-C regulates coronary blood flow and prevents myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: novel cardioprotective role for endothelium-derived C-type natriuretic peptide. Circulation 110:1231–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PJ, Richards AM, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Yandle TG. (1994) Bioactivity and metabolism of C-type natriuretic peptide in normal man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki T, Itoh H, Suga SI, Hama N, Ogawa Y, Komatsu Y, Yamashita J, Doi K, Chun TH, Nakao K. (1998) Effects of intravenously administered C-type natriuretic peptide in humans: comparison with atrial natriuretic peptide. Hypertens Res 21:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igawa A, Ukai T, Tachibana H, Zhang ZS, Cheng HJ, Little WC, Cheng CP. (2000) Effect of nesiritide on left ventricular systolic and diastolic performance at rest and during exercise after heart failure (Abstract) Circulation 102(18, Suppl):II-531. [Google Scholar]

- Jorde UP, Vittorio TJ, Kasper ME, Arezzi E, Colombo PC, Goldsmith RL, Ahuja K, Tseng CH, Haas F, Hirsh DS. (2008) Chronotropic incompetence, beta-blockers, and functional capacity in advanced congestive heart failure: time to pace? Eur J Heart Fail 10:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra PR, Clague JR, Bolger AP, Anker SD, Poole-Wilson PA, Struthers AD, Coats AJ. (2003) Myocardial production of C-type natriuretic peptide in chronic heart failure. Circulation 107:571–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass DA. (2012) Heart failure: a PKGarious balancing act. Circulation 126:797–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. (2010) Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Circ Heart Fail 3:659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kociol RD. (2012) Circulation: Heart Failure editor’s picks: most important articles in heart failure and therapeutics. Circ Heart Fail 5:e73–e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M. (2015) Cardiac actions of atrial natriuretic peptide: new visions of an old friend. Circ Res 116:1278–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladage D, Schwinger RH, Brixius K. (2013) Cardio-selective beta-blocker: pharmacological evidence and their influence on exercise capacity. Cardiovasc Ther 31:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenickel TH, Dole WP. (2012) Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibition with LCZ696: a novel approach for the treatment of heart failure. Drug Discov Today Ther Strateg 9:e131–e139. [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. (1998) Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med 339:321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little WC, Borlaug BA. (2015) Exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: what does the heart have to do with it? Circ Heart Fail 8:233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little WC, Cheng CP. (1993) Effect of exercise on left ventricular-arterial coupling assessed in the pressure-volume plane. Am J Physiol 264:H1629–H1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little WC, Kitzman DW, Cheng CP. (2000) Diastolic dysfunction as a cause of exercise intolerance. Heart Fail Rev 5:301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden NG, Khambata RS, Hobbs AJ. (2010) C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP): cardiovascular roles and potential as a therapeutic target. Curr Pharm Des 16:4080–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutani S, Senzaki H. (2011) Left ventricular function in adult patients with atrial septal defect: implication for development of heart failure after transcatheter closure. J Card Fail 17:957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall D, Fried TA. (1990) Effect of atriopeptin II on Ca influx, contractile behavior and cyclic nucleotide content of cultured neonatal rat myocardial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 22:201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S, Guth BD, Miura T, Indolfi C, Schulz R, Ross J., Jr (1990) Changes of left ventricular diastolic function in exercising dogs without and with ischemia. Circulation 81:1058–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe GW, Canepa-Anson R, Armstrong PW. (1992) Atrial natriuretic factor: pharmacokinetics and cyclic GMP response in relation to biologic effects in severe heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 19:691–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe GW, Forster C, de Bold AJ, Armstrong PW. (1990) Pharmacokinetics, hemodynamic, renal, and neurohormonal effects of atrial natriuretic factor in experimental heart failure. Clin Invest Med 13:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moltzau LR, Aronsen JM, Meier S, Nguyen CH, Hougen K, Ørstavik Ø, Sjaastad I, Christensen G, Skomedal T, Osnes JB, et al. (2013) SERCA2 activity is involved in the CNP-mediated functional responses in failing rat myocardium. Br J Pharmacol 170:366–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moltzau LR, Aronsen JM, Meier S, Skogestad J, Ørstavik Ø, Lothe GB, Sjaastad I, Skomedal T, Osnes JB, Levy FO, et al. (2014a) Different compartmentation of responses to brain natriuretic peptide and C-type natriuretic peptide in failing rat ventricle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350:681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moltzau LR, Meier S, Aronsen JM, Afzal F, Sjaastad I, Skomedal T, Osnes JB, Levy FO, Qvigstad E. (2014b) Differential regulation of C-type natriuretic peptide-induced cGMP and functional responses by PDE2 and PDE3 in failing myocardium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 387:407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto A, Hasegawa H, Cheng HJ, Little WC, Cheng CP. (2004) Endogenous beta3-adrenoreceptor activation contributes to left ventricular and cardiomyocyte dysfunction in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286:H2425–H2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Hagiike M, Horiba T, Miyake K, Ohyama H, Yamanouchi H, Hosomi H, Kangawa K, Minamino N, Matsuo H. (1992) Effects of brain natriuretic peptide and C-type natriuretic peptide infusion on urine flow and jejunal absorption in anesthetized dogs. Jpn J Physiol 42:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Arakawa N, Yoshida H, Makita S, Hiramori K. (1994) Vasodilatory effects of C-type natriuretic peptide on forearm resistance vessels are distinct from those of atrial natriuretic peptide in chronic heart failure. Circulation 90:1210–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Arakawa N, Yoshida H, Makita S, Niinuma H, Hiramori K. (1998) Vasodilatory effects of B-type natriuretic peptide are impaired in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J 135:414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narang R, Swedberg K, Cleland JG. (1996) What is the ideal study design for evaluation of treatment for heart failure? Insights from trials assessing the effect of ACE inhibitors on exercise capacity. Eur Heart J 17:120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohte N, Cheng CP, Little WC. (2003) Tachycardia exacerbates abnormal left ventricular-arterial coupling in heart failure. Heart Vessels 18:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohte N, Cheng CP, Suzuki M, Little WC. (1999) Effects of atrial natriuretic peptide on left ventricular performance in conscious dogs before and after pacing-induced heart failure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens AT, Brozena SC, Jessup M. (2016) New management strategies in heart failure. Circ Res 118:480–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel-Langenickel I, Buttgereit J, Bader M, Langenickel TH. (2007) Natriuretic peptide receptor B signaling in the cardiovascular system: protection from cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Med (Berl) 85:797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham I, Sediame S, Maistre G, Roudot-Thoraval F, Chabrier PE, Carayon A, Adnot S. (1997) Renal and vascular effects of C-type and atrial natriuretic peptides in humans. Am J Physiol 273:R1457–R1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierkes M, Gambaryan S, Bokník P, Lohmann SM, Schmitz W, Potthast R, Holtwick R, Kuhn M. (2002) Increased effects of C-type natriuretic peptide on cardiac ventricular contractility and relaxation in guanylyl cyclase A-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res 53:852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qvigstad E, Moltzau LR, Aronsen JM, Nguyen CH, Hougen K, Sjaastad I, Levy FO, Skomedal T, Osnes JB. (2010) Natriuretic peptides increase beta1-adrenoceptor signalling in failing hearts through phosphodiesterase 3 inhibition. Cardiovasc Res 85:763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M, Opotowsky AR, Shah AM, Tracy J, Waxman AB, Systrom DM. (2015) Central cardiac limit to aerobic capacity in patients with exertional pulmonary venous hypertension: implications for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 8:278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammas FV, Dickstein K. (1988) Clinical pharmacokinetics in heart failure: an updated review. Clin Pharmacokinet 15:94–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood J, Ashton M, Newton C, Biles S. (2011) Current and future options for the management of heart failure. Pharm J 286:437. [Google Scholar]

- Singh JS, Lang CC. (2015) Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors: clinical potential in heart failure and beyond. Vasc Health Risk Manag 11:283–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinale FG, Walker JD, Mukherjee R, Iannini JP, Keever AT, Gallagher KP. (1997) Concomitant endothelin receptor subtype-A blockade during the progression of pacing-induced congestive heart failure in rabbits. Beneficial effects on left ventricular and myocyte function. Circulation 95:1918–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingo AJ, Clavell AL, Aarhus LL, Burnett JC., Jr (1992) Cardiovascular and renal actions of C-type natriuretic peptide. Am J Physiol 262:H308–H312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H, Kitabatake A, Sagawa K. (1979) End-systolic pressure determines stroke volume from fixed end-diastolic volume in the isolated canine left ventricle under a constant contractile state. Circ Res 44:238–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Ohte N, Wang ZM, Williams DL, Jr, Little WC, Cheng CP. (1998) Altered inotropic response of endothelin-1 in cardiomyocytes from rats with isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 39:589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima M, Bartunek J, Weinberg EO, Ito N, Lorell BH. (1998) Atrial natriuretic peptide has different effects on contractility and intracellular pH in normal and hypertrophied myocytes from pressure-overloaded hearts. Circulation 98:2760–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto E. (2012) Cyclic GMP-dependent signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ J 76:1819–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbe U, Scholz KH, Kreuzer H, Neuhaus KL. (1987) Changes in left ventricular diastolic function during exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 8:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutamoto T, Wada A, Maeda K, Hisanaga T, Maeda Y, Fukai D, Ohnishi M, Sugimoto Y, Kinoshita M. (1997) Attenuation of compensation of endogenous cardiac natriuretic peptide system in chronic heart failure: prognostic role of plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration in patients with chronic symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 96:509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollert KC, Yurukova S, Kilic A, Begrow F, Fiedler B, Gambaryan S, Walter U, Lohmann SM, Kuhn M. (2003) Increased effects of C-type natriuretic peptide on contractility and calcium regulation in murine hearts overexpressing cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I. Br J Pharmacol 140:1227–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RS, Wei CM, Kim CH, Kinoshita M, Matsuda Y, Aarhus LL, Burnett JC, Jr, Miller WL. (1996) C-type natriuretic peptide-mediated coronary vasodilation: role of the coronary nitric oxide and particulate guanylate cyclase systems. J Am Coll Cardiol 28:1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Cheng HJ, Hasegawa H, Morimoto A, Cross M, Cheng CP. (2009) Enhanced C-type natriuretic peptide positive modulation on cardiac performance in heart failure: effects on left ventricle and myocyte contraction, [Ca2+]i transient and Ca2+ current. abstract Circulation 120(18, Suppl):S820. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.