Abstract

Among many possible benefits, global health efforts can expand the skills and experience of U.S. clinicians, improve health for communities in need, and generate innovations in care delivery with relevance everywhere. Yet, despite high rates of interest among students and medical trainees to include global health opportunities in their training, there is still no clear understanding of how this interest will translate into viable and sustained global health careers after graduation. Building on a growing conversation about how to support careers in academic global health, this Perspective describes the practical challenges faced by physicians pursuing these careers after they complete training. Writing from their perspective as junior faculty at one U.S. academic health center with a dedicated focus on global health training, the authors describe a number of practical issues they have found to be critical both for their own career development and for the advice they provide their mentees. With a particular emphasis on the financial, personal, professional, and logistical challenges that young “expat” global health physicians in academic institutions face, they underscore the importance of finding ways to support these career paths, and propose possible solutions. Such investments would not only respond to the rational and moral imperatives of global health work and advance the mission of improving human health but also help to fully leverage the potential of what is already an unprecedented movement within academic medicine.

The last decade has brought an explosion of interest in global health among students and medical trainees in the United States. This trend spans all levels of training, from undergraduates majoring in global health to medical students traveling abroad for rotations, to medical school graduates choosing residency programs based on related opportunities. Global health is shaping the education of many future physicians, and an important number are looking to make it a focus in their careers.1

Overflowing Interest in Global Health: Where Is It Heading?

“Global health” is defined in many ways, but we consider it to be any effort, domestic or international, driven by the purpose of improving the “health of all” across borders and socioeconomic distinctions. Although global health includes health-related activities in low-income countries, it is much broader than these efforts; global health is a field that integrates many disciplines (including public health, management, and the social sciences) to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice to impact lives everywhere.2 With growing interest in the field, global health has the potential to improve health in the most vulnerable communities, with collateral benefits for everyone, regardless of their home country or socioeconomic status.3,4 For academic health centers, global health offers opportunities to generate innovations in care delivery and research challenges unique to settings of poverty (but potentially relevant to health systems anywhere), and to provide trainees with exposure to a wider range of diseases, cultures, and socioeconomic circumstances.5

Despite these very real benefits, there is a dearth of structured pathways for translating enthusiasm for global health into viable, long-term careers within academic medicine. Although many articles have examined global health training,6 few have explored the experiences of physicians pursuing careers in this field after training. One survey of 521 graduates from a clinical scholars program that attracts physicians with interests in global health suggests an uncomfortable reality: Only 44% reported some global health activity after graduation, and 73% of that subgroup reported spending not even 10% of their professional time the year prior on global health efforts abroad.7 Family considerations and a lack of career development opportunities were cited among important barriers.

As recent graduates and current faculty in one of the first residency programs dedicated to global health, the Howard Hiatt Residency in Internal Medicine and Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, we have experienced many of these challenges firsthand, and we have seen them reflected in the experiences of our colleagues and mentees. We describe the practical demands of doing global health abroad amid personal and family commitments and an academic landscape only partially aligned with these efforts. We draw these themes from our own experiences, discussions with peers, as well as the best available literature. To find relevant articles, we used the Google Scholar search engine with the keywords “global health careers,” “expat workers,” and “work-life balance,” and then used a form of snowball sampling to identify additional publications from the references.

We acknowledge from the start that there are limitations to the perspective we offer. First, we are only two faculty members building our careers in a single academic institution with a track record for supporting global health, and as such we see the need to cultivate global health careers as a priority. Second, we examine these careers primarily through the lens of U.S.-trained physicians in nonsurgical specialties, though similar insights likely apply to surgical professions and other health care cadres. We characterize the experiences closest to our own and those of our peers in order to speak with clarity, but we recognize that global health straddles many disciplines and promotes a diversity of experiences that will not always fit within a unified trajectory. While acknowledging that many domestic efforts also constitute global health activities,8,9 we focus primarily on work abroad as an expatriate, or “expat,” physician because this pathway creates unique challenges that we have lived and feel should be more openly discussed. Lastly, we address careers of physicians trained in the Global North, but this does not imply that the perspectives and challenges of the North hold dominion.10 The landscape of human resource development is fundamentally changing everywhere,11 but U.S.-trained physicians remain disproportionately privileged in many ways. We know that our career troubles often pale in comparison to those of our colleagues elsewhere; much of our own global health work is precisely in response to the challenges faced in these settings.12–14 This Perspective addresses one side of this story: how to best support the supporters. It is ethically imperative, however, that any such effort should hold as a core objective “mutual and reciprocal benefit” for all partners involved.15

This Perspective should be the first of many. As studies are conducted and global health workers of different stripes and institutions reflect on their experiences, we hope our insights are enhanced and challenged to provide a clearer and more complete picture of academic careers within global health.

Academic Career Models and Global Health

The traditional academic career model is based on the Oslerian ideal of the “triple threat”: the physician who excels in teaching, research, and clinical care.16 Because of the increasing sophistication of medicine and the time commitment now required to contribute to research and teaching, most academicians divide their contracted work time, or full-time equivalency (FTE), between one or two of the three. Most academic health centers frame career development pathways for these variations, including the full-time clinician, clinician–educator, or clinician–researcher.17 Each pathway has its own trade-offs: 100% FTE clinicians may receive higher salaries but experience less flexible and more unpredictable work schedules due to patient care issues; clinician–researchers may enjoy pursuing new science and being experts in their field, but constantly struggle to obtain grants. Most academic physicians are expected to teach, so these efforts are only sometimes reimbursed incrementally.18

Many academic physicians start their careers with the majority of their time devoted to clinical care and a smaller proportion to research or teaching. If a physician rises in the ranks as a researcher (e.g., finds independent funding from the National Institutes of Health) or as an educator (e.g., assumes a leadership role in a residency program that provides salary support), this split may reverse with progressively less time dedicated to clinical practice and more reserved for research or training. Throughout this evolution, most physicians earn a salary on par with academic colleagues in the same specialties and at similar stages in their career, and gain academic promotion by publishing in the academic literature. The move away from clinical care opens up logistical and mental space to focus on creating such academic currency.19

Academic physicians pursuing careers in global health abroad similarly divide their efforts, often between clinical activities in their home country and global health activities abroad. For the latter, some engage in global-health-related research, whereas others work with nongovernmental organizations, governments, or technical agencies (e.g., the World Health Organization) on direct service delivery, health systems strengthening, or policy. Some physicians may be involved with training health care professionals abroad or teaching about global health in the United States. Still others will piece together combinations of these activities.20

Given the diversity of roles and the lack of established pathways, expat global health physicians sometimes struggle to construct a schedule that enables them to simultaneously pursue their global health interests, earn a sufficient income, and accrue the credentials needed for academic promotion.

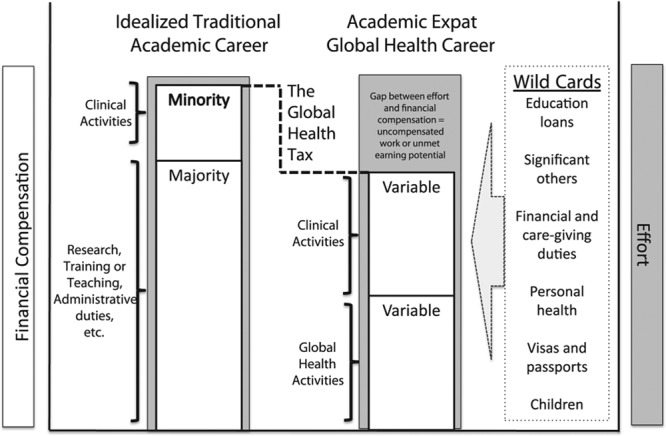

Some pathways (e.g., the clinician–researcher who conducts HIV studies abroad through an infectious disease department) allow access to existing mechanisms for research funding, career mentorship, and academic advancement. Our experience, however, has been that most expat global health physicians will not have these benefits available to them because of the nature of their work. As a result, funding and academic promotion may be particularly difficult. Someone pursuing global health work outside of traditional research may design policies, build health systems that improve the health of thousands, and be celebrated as a leader in their field, but fail to generate the traditional peer-reviewed “documentation” needed to advance academically. Figure 1 illustrates these tensions unique to expat global health careers graphically.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of an “expat” academic global health career. In the idealized traditional academic career, effort is commensurate with financial compensation via a full-time equivalency (FTE) contract, whereas in the expat academic global health career, effort is similar to that of other colleagues in academic medicine, but there is a gap in compensation generated by uncompensated work or unmet earning potential. The bars representing compensation show the proportion provided by each type of effort; where the traditional career’s compensation bar is clearly divided between majority and minority efforts because of the opportunities offered by compensated research, teaching, or administrative efforts, the expat career is often less clearly structured. As a result, the global health physician often needs to negotiate more variables and face greater uncertainty, and therefore is more prone to their career path being derailed by the listed “wild cards” (life challenges).

Global health researchers who also work as implementers and/or policy experts may face a career path fraught with challenges. Such researchers often explore how to integrate “research findings and evidence into healthcare policy and practice” through what is called implementation science21 or delivery science.22 This field of inquiry, however, is still nascent, as “scientists have been slow to view implementation as a dynamic, adaptive, multiscale phenomenon that can be addressed through a research agenda.”23 Also, there is a dearth of training programs in this field “in part because the skill set has not been adequately defined and continues to evolve,”24 and the quality and supply of mentors for this career track only sometimes meets the demand.25 Funding is difficult for all researchers,26 but it is particularly problematic for global health researchers, who usually do not access industry sources and must often rely on competitive government grants, such as from the Fogarty International Center.27 Further, global health research may require new approaches calibrated to working cross-culturally and cross-nationally.28 We have seen personally how working within such arrangements and in settings with debilitated institutions creates challenges that can undermine research, such as the difficulty in organizing ethical review for research protocols, reliably collecting data, and navigating political and operational realities that can cause unpredictable disruptions.

The Global Health Tax

Many global health efforts take place in underresourced communities and have minimal funds available to provide salary support. For example, one survey of hospitalists found that 78% of those doing global health work received no funding for these efforts.29 Some expat physicians rely on their clinical time in the United States to subsidize their efforts, which compels them either to pick up additional clinical work, thereby reducing their global health time abroad, or to take a deliberate pay cut and accept that their work abroad will be de facto pro bono. We term this pay cut the “global health tax,” not because it is onerous but because this income reduction may go toward creating the kinds of social public goods usually financed by taxes. Many global health doctors willingly assume this financial burden, demonstrating the extent to which they are driven by a sense of purpose. The magnitude of the “tax” is determined by multiple factors, but for those spending a majority of their time on global health the amount could be substantial (i.e., more than 40%–75% of earning potential, or a drop of $100,000–$150,000 in some markets based on 2013 salaries,30 which we have seen can potentially reduce the total salary to as low as $60,000 or less for some).

Expat global health doctors need clinical work that allows flexible, part-time scheduling to accommodate travel abroad. This sometimes limits their practice options to emergency department shifts, overnight and weekend hospitalist work, urgent care clinics, and various moonlighting and locum tenens jobs. Primary care work is often impossible because of the ongoing needs of caring for a panel of patients. Part-time global health hospitalists may be seen as “strange but noble bedfellows” by their group leadership,31 in part because of the logistical barriers they face in participating in value-generating and identity-forming activities, such as quality improvement and local hospital systems development projects. For many specialties outside of internal medicine or emergency medicine, this type of flexible scheduling may not even be possible.

The Wild Cards

Expat global health careers require navigating a variety of challenges that demand living in a precarious balance that can—even for the most committed physician—be disrupted by unavoidable and unexpected circumstances. We colloquially term these factors the “wild cards” of a career in global health. This is true to varying degrees for many academic physicians,32 but the challenges that may be seen as surmountable by domestic physicians can thwart, if not end, an expat global health career. The business world has long known about challenges facing the “expat worker,”33 and there is a substantial literature on how to help these employees stay healthy and productive.34 It is in this spirit that similar efforts should be considered for global health.

Common challenges may inflict more damage on an expat career

Repaying education loans, forming and sustaining relationships with significant others, achieving a work–life balance, raising children well, and carrying out other familial, financial, and caregiving duties are some of the issues that nearly all professionals will have to confront at some point. The global health expat physician, however, often has to negotiate these concerns in a way that accounts for what is usually a lower salary, the logistics of frequent travel, and, often, living in contexts with less personal security.

For example, in 2014, 84% of medical students graduated with outstanding loans at a median debt of $180,00035; such a financial burden may cause the potentially lower salaries of a global health career to become untenable. Although current “income-based repayment” plans offer one pathway for repayment and partial forgiveness of education loans,36 if this program were modified or eliminated in a political cross-fire, global health physicians who could no longer rely on this option may face new, and career-altering, uncertainty. In addition, frequent travel abroad, coupled with long and odd hours while in the United States, can strain any personal relationship, but especially one with a significant other.37 Further, having children while pursuing an expat career in global health demands negotiating difficult decisions; among a number of challenges, the financial responsibilities of parenthood, such as paying for daycare when covering clinical shifts in the United States, may make the global health tax prohibitive, and concerns about health, education, and safety may preclude some from raising children abroad.38

Aging parents and family crises may compel physicians to spend less time abroad and look for higher compensation in order to take on greater caregiving and economic roles within their families. Similarly, many who have accommodated short-term financial challenges have told us that they worry about their long-term financial security because they are not building equity or saving enough for retirement.

Challenges unique to expat global health

There are a number of hazards that expat physicians have come to accept as “part of the job,” but that acceptance does not mean that the burden should not be mitigated. For example, global settings sometimes put physicians at increased risk of injury and illness, including mental health problems from exposure to extreme circumstances.39–42 Becoming afflicted with a significant illness that requires frequent specialized care and avoidance of harsh conditions can abruptly halt an expat career.

Another related challenge is the ability to move freely across borders, a privilege that citizens from the Global North may take for granted but that is a very real concern for many who cannot obtain the necessary visas to enter certain countries. This can hurt the field in many ways. For example, clinicians from foreign countries who train in the United States may be among the most appropriate candidates to work in global health; they may also experience the greatest challenges in travel by not being allowed into countries hosting global health activities, or even allowed to layover in other countries on the way to work sites. This, along with the challenges in receiving sponsorship from a U.S.-based employer for jobs involving time abroad, may deter foreign physicians training in the United States from considering global health, even when it aligns with their interests and experience.

Cultivating Academic Careers in Global Health

Greater supportive structures and funding must be established in order to translate the surge in enthusiasm for global health into sustainable careers.43 Table 1 offers some possible solutions that could be considered. Further research will help clarify how best to foster these careers; we are currently conducting such a study on the postresidency experiences of graduates from our Global Health Equity Residency at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

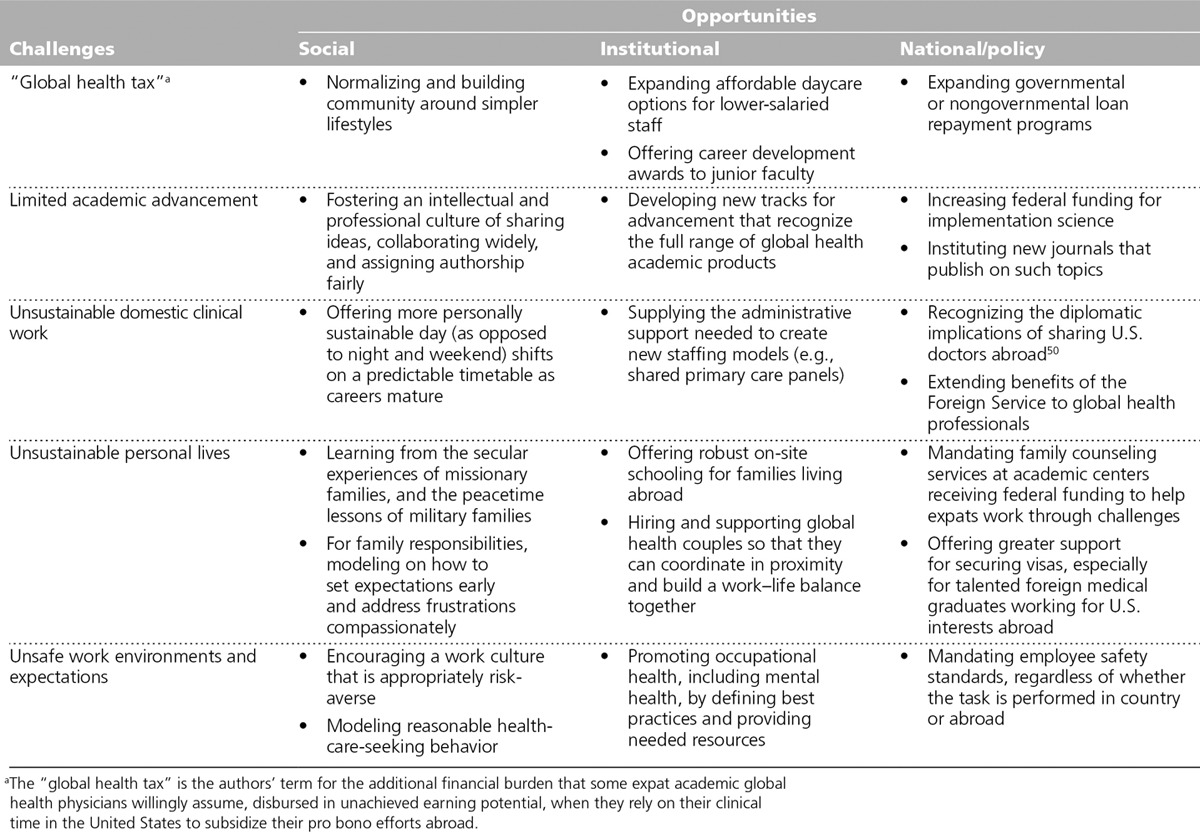

Table 1.

Opportunities to Address Challenges in “Expat” Academic Global Health Career Development

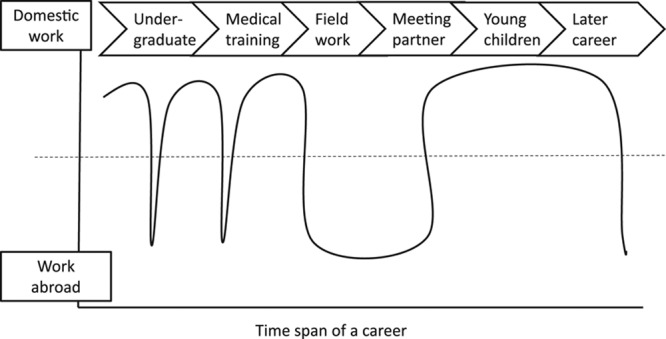

Because of these challenges, as well as the increasing opportunities to address similar global health themes at home as the U.S. health care system undergoes its own reformation, we see many colleagues start out in global health abroad and then, once confronted by wild cards, transition to domestic work with the aspiration to return to international activities once they have raised children and gained secure footing financially and academically. Figure 2 shows one possible career trajectory taken by some, though many variations exist. Such movement between domestic and expat work may allow physicians to incorporate the best of global health while balancing evolving practicalities. Moreover, the cross-fertilization of U.S. health reform with global-health-experienced physicians is a welcome possibility that can enhance both domestic and global efforts, particularly as the challenges of care delivery and disease burden converge. The viability of global health as a field, nevertheless, cannot rest purely on serving as a farm system for domestic action; there are many issues in the global sphere that require unique attention, as well as a cadre of physicians seeking to work specifically in these settings. The pathway in Figure 2 has been shaped, and limited, by current assumptions about what careers in academic global health can be. We believe a better way is achievable. To expand the possibilities for such careers, academic health center leaders and staff need to strike a better balance between the level of support given for global health activities, the importance of the work, and the expectations of participants.

Figure 2.

One of many possible “expat” academic global health career trajectories. Across the span of a global health career, professional activities can oscillate between domestic work and work abroad. The line represents one such pathway over time, showing how a sample physician transitioned from education to work abroad early in the career and back to domestic work as family-related responsibilities grew. This is not an idealized pathway, and physicians may follow many trajectories as they work to balance professional and personal opportunities with factors that enable them to achieve their goals and fulfill their responsibilities. The authors question how other career trajectories might be made possible.

Imperative Next Steps

Interest in global health is having an undeniable influence on education and training across the medical education spectrum.44 The current generation of physicians is the first to enter into global health as a nearly established, yet still nascent, field. These physicians are akin to entrepreneurs in a “start-up,” pushing out into a new arena with few guideposts and great risk.45 This entrepreneurial spirit coupled with global health’s sense of purpose is partially what makes it an exciting field. Our question is, once the appetite for such dynamism passes, what will become of these “early adopters?” Fraught with personal, financial, and academic hurdles, how scalable and maintainable is the current academic career model in expat global health?

Academic health centers can play a critical role in helping to shape this unplanned but powerful movement so that it can achieve its full potential. Beyond the moral or rational arguments for supporting global health, there are many practical benefits for academic health centers. For example, the opportunity to invigorate discussion within their own intellectual community and produce widely influential academic products strengthens these academic institutions and augments the role they play in society at large.46,47 But these benefits will not come without commitments from institution leaders.48,49 Innovative accommodations for global health careers, such as career development awards and tailored paths for academic promotion, would go a long way to make this work feel more valued and less of a life challenge. Novel solutions to the challenges inherent in expat global health work, such as shared patient panels in U.S. primary care clinics with commitments to staff year-round clinician–educator roles at partner institutions abroad, would open up incredible new opportunities for sustained involvement. We have seen firsthand how the return promised by such investments is inspirational.

The current scenario, however, leaves only those willing to take these risks, closing the door on many who would have an interest and ability to contribute to the field. We fear that if the current model does not evolve to meet these challenges, the current crest of interest in global health may taper off, and any prospect of leveraging it for bigger impact may disappear. Are we ready to accept these lost opportunities?

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Joseph Rhatigan, MD, and Sriram Shamasunder, MD, for commenting on an early draft of this article.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Birnberg JM, Lypson M, Anderson RA, et al. Incoming resident interest in global health: Occasional travel versus a future career abroad? J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:400–403. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00168.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macfarlane SB, Jacobs M, Kaaya EE. In the name of global health: Trends in academic institutions. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29:383–401. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartzman K, Oxlade O, Barr RG, et al. Domestic returns from investment in the control of tuberculosis in other countries. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1008–1020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom BR, Salomon JA. Enlightened self-interest and the control of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1057–1059. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grudzen CR, Legome E. Loss of international medical experiences: Knowledge, attitudes and skills at risk. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: Current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84:320–325. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greysen SR, Richards AK, Coupet S, Desai MM, Padela AI. Global health experiences of U.S. physicians: A mixed methods survey of clinician–researchers and health policy leaders. Global Health. 2013;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller D. Haiti. JAMA. 2011;305:447–448. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventres W, Page T. Bring global health and global medicine home. Acad Med. 2013;88:907–908. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182952940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horton R. Offline: The case against global health. Lancet. 2014;383:1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crisp N, Chen L. Global supply of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:950–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1111610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palazuelos D, Ellis K, Im DD, et al. 5-SPICE: The application of an original framework for community health worker program design, quality improvement and research agenda setting. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:19658. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhillon RS, Srikrishna D, Sachs J. Controlling Ebola: Next steps. Lancet. 2014;384:1409–1411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Wieren A, Palazuelos L, Elliott PF, Arrieta J, Flores H, Palazuelos D. Service, training, mentorship: First report of an innovative education-support program to revitalize primary care social service in Chiapas, Mexico. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25139. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crump JA, Sugarman J Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT) Global health training. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1178–1182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Periyakoil VS. What would Osler do? J Palliat Med. 2013;16:118–119. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levinson W, Linzer M. What is an academic general internist? Career options and training pathways. JAMA. 2002;288:2045–2048. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt T, Chung H, White H, Lyckholm LJ. Shaping your career to maximize personal satisfaction in the practice of oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4020–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin MH, Covinsky KE, McDermott MM, Thomas EJ. Building a research career in general internal medicine: A perspective from young investigators. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:117–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gewin V. The global challenge. Nature. 2007;447:348–349. doi: 10.1038/nj7142-348a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health. Frequently asked questions about implementation science. Updated May 2013. http://www.fic.nih.gov/News/Events/implementation-science/Pages/faqs.aspx. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- 22.Navathe A, Jain S, Jha A, Milstein A, Shannon R. Introducing you to healthcare: The Journal of Delivery Science and Innovation. Healthcare. 2013;1:1. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madon T, Hofman KJ, Kupfer L, Glass RI. Public health. Implementation science. Science. 2007;318:1728–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzales R, Handley MA, Ackerman S, O’sullivan PS. A framework for training health professionals in implementation and dissemination science. Acad Med. 2012;87:271–278. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182449d33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah SK, Nodell B, Montano SM, Behrens C, Zunt JR. Clinical research and global health: Mentoring the next generation of health care students. Glob Public Health. 2011;6:234–246. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.494248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadman M. One year at the helm. Nature. 2010;466:808–810. doi: 10.1038/466808a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health. Funding opportunities. http://www.fic.nih.gov/funding/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- 28.Stephen C, Daibes I. Defining features of the practice of global health research: An examination of 14 global health research teams. Glob Health Action. 2010;3 doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5188. doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoeb M, Le P, Greysen SR. Global health hospitalists: The fastest growing specialty’s newest niche. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:162–163. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Today’s Hospitalist. Are you happy with what you make? One in five hospitalists say they work too many hours for too little pay. Today’s Hospitalist Compensation & Career Guide. 2013. http://www.todayshospitalist.com/index.php?b=articles_read&cnt=1801#sthash.8XK6IbUD.dpuf. Accessed May 4, 2015.

- 31.Wachter B. Global health hospitalists: Strange but Nobel bedfellows. Wachter’s World. December 19, 2013. http://community.the-hospitalist.org/2013/12/19/global-health-hospitalists-strange-but-noble-bedfellows/. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- 32.Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, Ash AS, Brennan RT. Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2012;87:859–869. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182582b18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant-Vallone EJ, Ensher EA. An examination of work and personal life conflict, organizational support, and employee health among international expatriates. Int J Intercult Rel. 2001;25:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman DC, Thomas DC. Career management facing expatriates. J Int Bus Stud. 1992;23:271–293. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical student education: Debt, costs, and loan repayment fact card. October 2014. https://www.aamc.org/download/152968/data. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- 36.Delisle J, Holt A. Safety net or windfall? Examining changes to income-based repayment for federal student loans. New America Foundation Web site. October 2012. http://newamerica.net/publications/policy/safety_net_or_windfall. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- 37.Black JS, Stephens GK. The influence of the spouse on American expatriate adjustment and intent to stay in Pacific Rim overseas assignments. J Manage. 1989;15:529–544. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones S. Medical aspects of expatriate health: Health threats. Occup Med (Lond) 2000;50:572–578. doi: 10.1093/occmed/50.8.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim PL, Han P, Chen LH, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Expatriates ill after travel: Results from the Geosentinel Surveillance Network. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner A, Cohen T, Carter EJ. Tuberculosis among participants in an academic global health medical exchange program. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:841–845. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1669-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dandu M. Trainee safety in global health. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:826–827. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1753-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foyle MF, Beer MD, Watson JP. Expatriate mental health. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:278–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farmer PE. More than just a hobby: What Harvard can do to advance global health. Harvard Crimson. May 26, 2011. http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2011/5/26/health-global-training-medical/. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- 44.Nelson BD, Kasper J, Hibberd PL, Thea DM, Herlihy JM. Developing a career in global health: Considerations for physicians-in-training and academic mentors. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:301–306. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00299.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drayton W, Brown C, Hillhouse K. Integrating social entrepreneurs into the “health for all” formula. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:591. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.033928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merson MH. University engagement in global health. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1676–1678. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1401124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ackerly DC, Udayakumar K, Taber R, Merson MH, Dzau VJ. Perspective: Global medicine: Opportunities and challenges for academic health science systems. Acad Med. 2011;86:1093–1099. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitcomb ME. Promoting global health: What role should academic health centers play? Acad Med. 2007;82:217–218. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305acc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolars JC. Should U.S. academic health centers play a leadership role in global health initiatives? Observations from three years in China. Acad Med. 2000;75:337–345. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200004000-00009. Reference cited only in Table 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerry VB, Auld S, Farmer P. An international service corps for health—an unconventional prescription for diplomacy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1199–1201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]