Abstract

Whether patient satisfaction scores can act as a catalyst for improving health care is highly debated. Some argue that pursuing patient satisfaction is overemphasized and potentially at odds with providing good care because it leads providers to overtest and overtreat patients and to bend to unreasonable patient demands, all to improve their ratings. Others cite studies showing that high patient satisfaction scores correlate with improved health outcomes. Ideally, assessing patient satisfaction metrics will encourage empathy, communication, trust, and shared decision making in the health care delivery process. From the patient’s perspective, sharing such metrics motivates physicians to provide patient-centered care and meets their need for easily accessible information about their providers.

In this article, the authors describe a seven-year initiative, which began in 2008, to change the culture of the University of Utah Health Care system to deliver a consistently exceptional patient experience. Five factors affected the health system’s ability to provide such care: (1) a lack of good decision-making processes, (2) a lack of accountability, (3) the wrong attitude, (4) a lack of patient focus, and (5) mission conflict. Working groups designed initiatives at all levels of the health system to address these issues. What began as a patient satisfaction initiative evolved into a model for physician engagement, values-based employment practices, enhanced professionalism and communication, reduced variability in performance, and improved alignment of the mission and vision across hospital and faculty group practice teams.

In health care, two widely held, but inherently contradictory, beliefs have emerged. The first is that health care needs to be more patient centered,1,2 and the second is that patient satisfaction is both overemphasized and potentially opposed to good care. Underpinning this contradiction is the belief that although the health care industry should focus on the patient, it is the provider who has the ability and right to define what is a positive outcome. While the patient experience has been adopted as a measure of quality by both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the British National Health Service,3 research connecting patient satisfaction to health outcomes is limited and conflicting,3–9 as are professional opinions on its merits or harms.10–14 Reconciling these divergent points of view is critical to advancing health system redesign.

In February 2008, the University of Utah Health Care system launched an initiative called the Exceptional Patient Experience (EPE) with the mantra “Medical care can only be truly great if the patient thinks it is.” What began as a patient satisfaction initiative has evolved into a model for cultural transformation and has since become the cornerstone for other initiatives focused on quality and safety, patient-reported outcomes, and cost reduction.

In this article, we describe the first seven years of the EPE initiative. Recognizing that ours is a single institution’s experience, we emphasize that the lessons we learned are widely applicable. The steps we took in implementing this initiative take their cue from common management principles, which, as we illustrate here, apply well to health care.

About the University of Utah Health Care System

The University of Utah Health Care system is owned and fully operated by the University of Utah, a public university. It is a part of the University of Utah Health Sciences center, which is led by the senior vice president for health sciences, who reports to the president of the university, and who serves as the CEO of the health system, the dean of the School of Medicine, and the chair of the faculty group practice board of directors. The health care system operates 4 hospitals and 10 community clinics in the Salt Lake City metropolitan area. Pediatric care is provided through a joint venture with Intermountain Health Care. In total, the health system records approximately 1.4 million patient visits annually. As the state’s only medical school and academic health sciences center, the health system covers the full breadth and depth of services across a continuum of care, as well as an extensive state and regional telehealth network.

In 2008, the University of Utah Health Care system faced increasingly frequent patient complaints. Criticisms and complaints ranged from delays in the scheduling of appointments to insufficient wayfinding, poor communication, inadequate care coordination, and lack of professionalism. The health system’s overall Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) “Rate this hospital” performance rating ranked in the 34th percentile nationally, which corresponded to only 62.4% of HCAHPS survey respondents rating the health system as a 9 or 10 on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the ideal rating.

Quality metrics for the health system were average compared with those for other teaching hospitals. In 2008, it was ranked 50th in quality nationally by the University HealthSystem Consortium, which at the time included about 88 academic health systems from across the country.

Launch of the EPE Initiative

At a leadership retreat on February 4, 2008, the then senior vice president for health sciences (A.L.B.) read a number of patient complaint letters. He challenged participants to consider why the health system was unable to deliver a level of service and quality that would be considered excellent beyond expectations. In short, he asked how the health system could enable caregivers to provide an exceptional experience to every patient, every time, and at every point within the system.

The leadership retreat participants agreed on five root causes for the health system’s inability to deliver consistently exceptional care: (1) a lack of good decision-making processes, (2) a lack of accountability, (3) the wrong attitude, (4) a lack of patient focus, and (5) mission conflict. Working groups, co-led by a faculty member and an administrator, each took on one of these root causes. Additional working groups were established to address other issues that arose from the root cause analysis, including leadership training; values-based employment and retention, reward, and recognition; unit-based action plans; and communication.

The data that informed the root cause analysis and the subsequent working groups and initiatives were derived from anecdotal patient stories at the system level and from patient survey results at the local level. While the patient complaint letters provided the urgency for change, short video recordings of patients describing their exceptional experiences within the health system served as inspiration for staff and faculty and were presented at retreats, staff and faculty meetings, new employee orientation, and town halls.

Phase 1: Implementing Critical Initiatives

Establishing leadership in culture change

Historically, the University Hospitals and Clinics and the 16 clinical departments of the School of Medicine effectively had functioned as distinct entities. These organizations were united in 2004 to form the University of Utah Health Care system. In fact, the two parts of this unified system could not have been more different. Clear lines of accountability in the University Hospitals and Clinics sustained a secure, stable, and predictable focus on control, and common, shared measures of success thrived in this rules-driven environment. In contrast, led by independent, entrepreneurial individuals, the clinical departments’ measure of success was an individual’s ability to generate her or his own resources. To improve the patient experience, the EPE initiative aimed to align the culture of the unified health system around patient satisfaction and engagement while at the same time preserving the characteristics responsible for the success of each individual entity. As part of this process, department chairs worked with hospital administrators to appoint physicians to new leadership roles in clinical operations and ambulatory care as service line medical directors.

Collecting and reporting data

The University of Utah Health Care system adopted the Press Ganey Medical Practice survey (see List 1) and benchmarked its responses to those from national peers. Initially, patient satisfaction was assessed and tracked using mailed Press Ganey surveys. In January 2011, the health system became one of the first academic medical centers to shift to electronic questionnaires, which increased both the number of surveys sent as well as the number of responses received. In 2011, the number of responses received increased to 41,768 (19.1% response rate). Using national percentile rankings, Press Ganey survey results were converted to color-coded dashboards at the individual and team levels. Each quarter, clinical units established their own targets for improvement.

List 1.

Standard Subjects on the Press Ganey Medical Practice Survey Used to Develop the Exceptional Patient Experience Initiative at the University of Utah Health Care System

Overall access

Ease of getting clinic on phone

Convenience of office hours

Ease of scheduling appointments

Courtesy of registration staff

Moving through your visit

Information about delays

Wait time at clinic

Nurse/assistant

Friendliness/courtesy of nurse/assistant

Concern of nurse/assistant for problem

Care provider (CP)

Friendliness/courtesy of CP

CP explanations of problem/condition

CP concern for questions/worries

CP efforts to include in decisions

CP information about medications

CP instructions for follow-up care

CP spoke using clear language

Time CP spent with patient

Patients’ confidence in CP

Likelihood of recommending CP

Personal issues

How well staff protect safety

Sensitivity to patients’ needs

Concern for patients’ privacy

Cleanliness of practice

Overall assessment

Staff worked together

Likelihood of recommending practice

Fostering values-based employment

The University of Utah Health Care system revisited its mission, vision, and values and elected to expand its core values to include compassion, collaboration, innovation, responsibility, diversity, integrity, quality, and trust. During this process, faculty and staff reviewed existing cultural language and revised it to align with the EPE initiative.

The health system then launched a multistep values-based employment process focused on the recruitment, retention, and promotion of employees who delivered an exceptional patient experience.

Values-based recruitment.

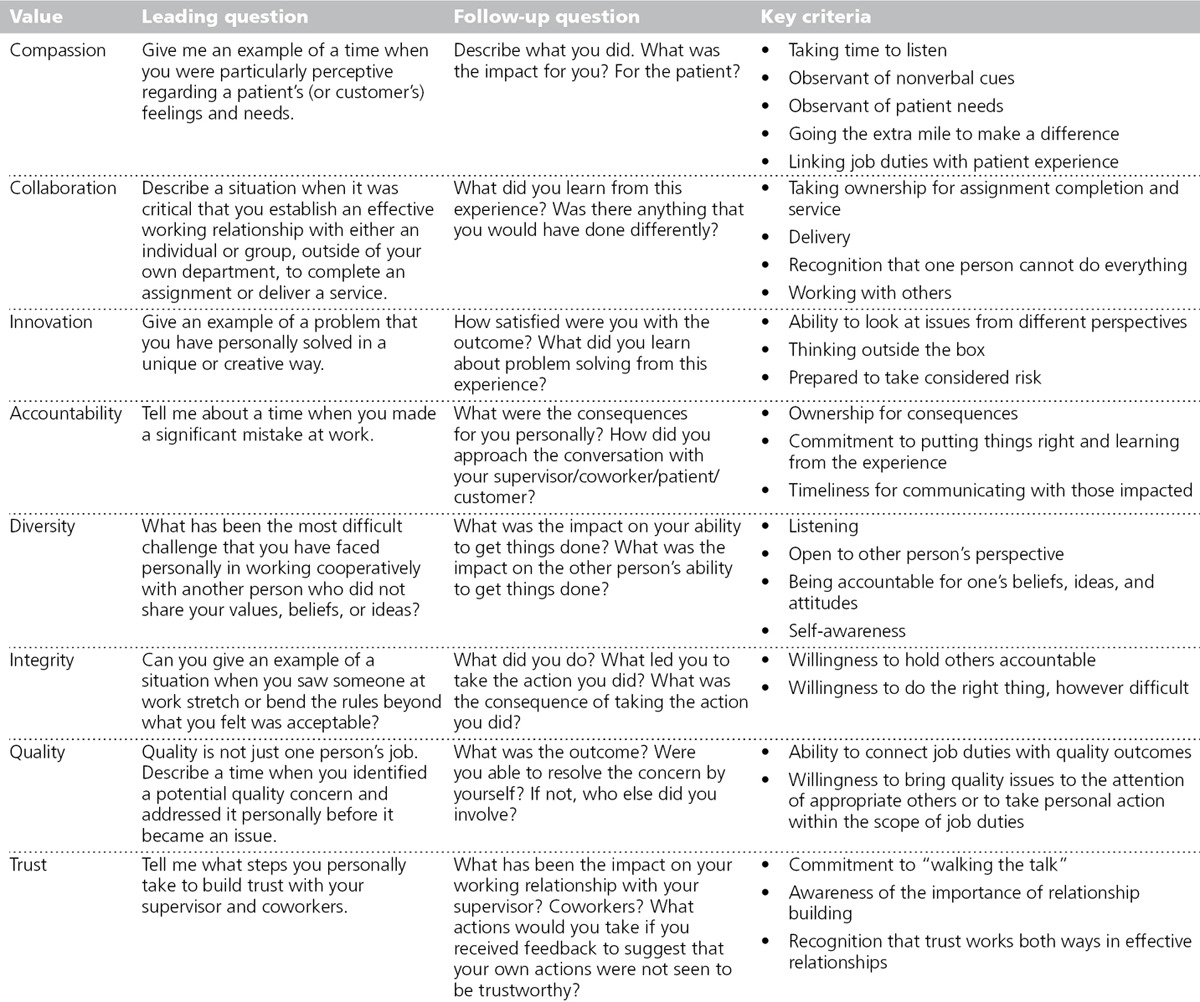

The values of the University of Utah Health Care system were included in all job descriptions and applicant screenings and interviews. All hiring supervisors, managers, and search committees were trained in values-based hiring. Targeted interview questions (see Table 1) were designed to assess applicants according to the EPE values.

Table 1.

Guidelines for Conducting a Values-Based Recruitment Interview, as Part of the Exceptional Patient Experience Initiative at the University of Utah Health Care System

Values-based retention and promotion.

Starting in 2008, patient satisfaction metrics were included in annual performance evaluations. Each clinical unit or department defined its own evaluation measurements. In addition, a focused redesign of human resource policies led to the development of a well-designed exit interview process, which became part of the feedback loop to improve performance.

Recognizing success

The hospital and faculty group practice set patient satisfaction targets for individual clinical units (inpatient and outpatient) with the ultimate goal of reaching the top 10th percentile of patient satisfaction nationally. Quarterly, a group of health system leaders, typically the CEO or chief operating officer of the University Hospitals and Clinics, the senior vice president for health sciences, and the chair of the Hospital Community Board, visited the clinical units that met or exceeded their targets. As part of these celebrations, specific patient comments were read aloud, the individuals cited in these comments received special recognition, and the unit received a framed citation. This practice continues today.

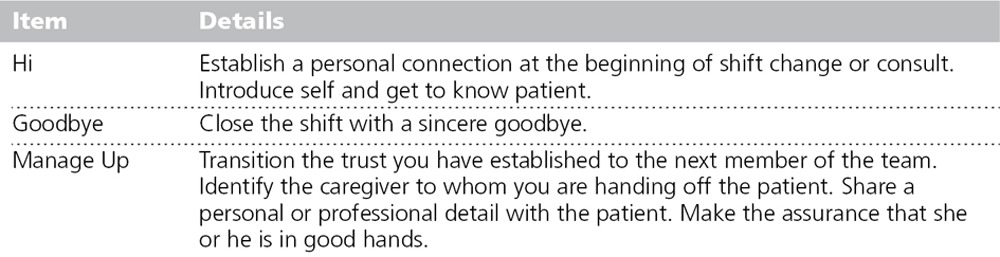

Creating unit-specific action plans

Across clinical units and service lines, leaders worked with their staff to determine specific strategies for improving the patient experience. This process led to significant innovation across the health system. Best practices were recognized, regularly shared, and implemented in an individualized manner specific to each department or service. For example, for the Cardiovascular Service Line, the scope of their EPE initiatives ranged broadly from individual pocket cards that identified the “gold standards” of exceptional cardiovascular care to scheduling adjustments to reduce the wait times for patients to schedule appointments. Provider scheduling templates were reviewed and revised, and in some cases, hours of operation were adjusted and extended. The University Neuropsychiatric Institute instituted a “Hi, Goodbye, Manage Up” practice (see Table 2) for staff working with patients in the hospital. The Huntsman Cancer Institute leaders accelerated innovation by meeting with each physician and her or his team—nurses, front desk and medical assistant staff—to emphasize a team approach to improving patient satisfaction.

Table 2.

University Neuropsychiatric Institute “Hi, Goodbye, Manage Up” Initiative, Developed as Part of the Exceptional Patient Experience Initiative at the University of Utah Health Care System

Engaging students and residents

In early 2011, we began to actively engage residents in the EPE initiative, recognizing that the principles of the initiative were concordant with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education common program requirements of professionalism, personal responsibility, and patient safety. Since then, expectations, processes, and sample scenarios have been presented routinely at all house officer orientation sessions. In addition, individual departments and divisions have integrated EPE initiatives into their training programs. For example, the orthopedic surgery service was the first to integrate residents by engaging them in improving inpatient rounds in the hospital. As a result, physician communication, management of pain, and readiness for discharge each improved.

Improving communication

In communicating about the EPE initiative internally, we focused on developing greater trust between patients and providers and among staff. Messages included the clear articulation of values, staff and patient stories gathered via an online tool, staff and patient videos, and best practices developed and shared across the health system. Communications channels included personal meetings between the senior vice president and department leaders, intranet and internal print newsletters, and health system retreats and symposia.

Phase 2: Physician Engagement and Data Transparency

Key to physician engagement in the EPE initiative was the sharing of patient feedback and the progressive transparency of those data coupled with coaching and the sharing of best practices to improve performance. Initially, department chairs could view department-level performance data for their faculty. In 2010, individual-level data were made available; these data were benchmarked to the national database to provide national percentile rankings. They were presented as simple dashboards for each provider.

The natural tendency toward competition began to drive improvements in patient satisfaction. Over time, within divisions, providers could compare their own patient satisfaction data with those of their peers. High performers were recognized, and low performers were offered coaching. Departments then began to increase transparency without administrative prompting. For example, at a faculty meeting in 2009, the chair of the department of dermatology made the patient satisfaction data for each individual provider in his department available for comparison; other departments followed suit.

In December 2012, after several months of internal discussion and preparation, the University of Utah Health Care system began to post each provider’s patient satisfaction data—scores and comments—on the university’s public Web site (e.g., http://healthcare.utah.edu/fad/mddetail.php?physicianID=u0102229).

Each provider’s “overall willingness to recommend” score from the Press Ganey survey was also added to the online profiles. This score, which averaged responses to all 10 survey questions, is represented using the familiar five yellow stars scheme. In addition, viewers can review individual survey question scores and unedited patient comments for each provider. A link to a description of the survey and the data source is provided as well. Less than 1% of patient comments need to be removed because of defamatory content. Comments are updated every 10 days, while scores are updated biannually.

EPE Resources and Staffing

For Phase 1, the EPE initiative was staffed by a core support team that included the chief medical officer, the assistant vice president for strategic initiatives, and, over time, up to four staff members (3.5 full-time equivalents). Working groups and additional EPE committees carried out the vast majority of the planning work. Faculty and staff were released from their other duties to attend these meetings. In addition, the chief medical officer identified and engaged medical directors and clinic managers from each clinic to foster frontline management skills to improve operations. Finally, the core support team provided initial coaching, while those at the medical director and clinic manager level provided additional coaching.

The chief medical officer led the Phase 2 efforts, working with the director of strategic initiatives, whose teams focused on teaching the health system the importance of public online reviews. The senior director of interactive marketing and Web and four staff members from the data warehouse focused on the development of the Web interface and on search engine optimization.

Impact of the EPE Initiative

Patient satisfaction metrics

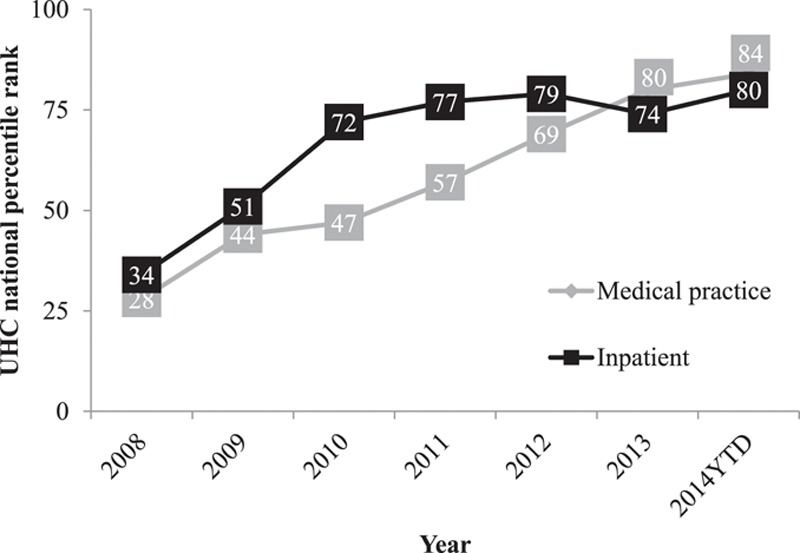

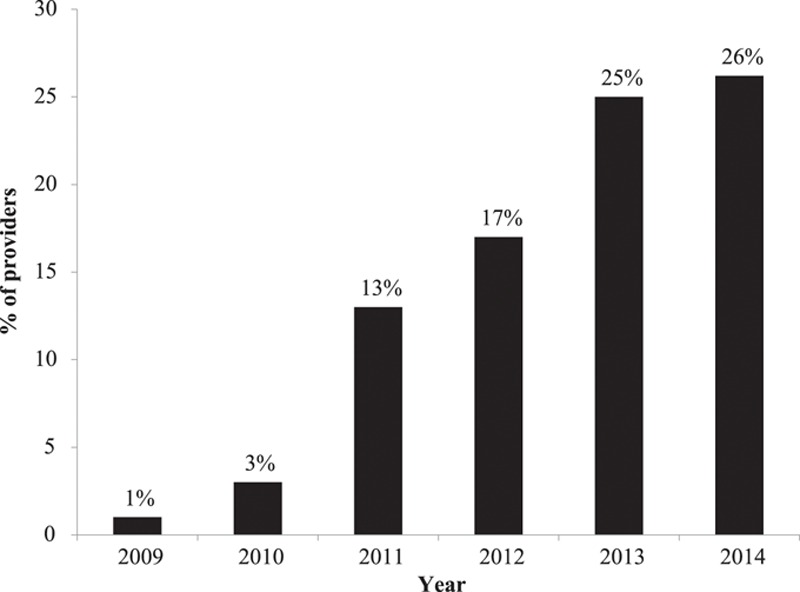

Over the past seven years, patient satisfaction has significantly increased (see Figure 1). Improvements at the individual provider level are most notable. Of the 453 providers who had 30 or more surveys returned in 2014, 50% ranked in the top 10% (raw score at or above 95.4) when compared with their peers nationally. Moreover, 26% ranked in the top 1% nationally (raw score at or above 96.7; see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Patient satisfaction with the University of Utah Health Care system. Press Ganey Medical Practice survey results and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems ratings of 9 or 10 (on a scale of 1–10) were compared against quality metrics for the teaching hospitals in the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) over the course of the Exceptional Patient Experience initiative, 2008 to September 2014.

Figure 2.

Percentage of providers at the University of Utah Health Care system with patient satisfaction scores in the top one percentile, benchmarked against the Press Ganey Medical Practice survey database. Only the 453 providers who had at least 30 surveys returned that year were included in the comparison.

Although the patient satisfaction survey response rate decreased from that in 2011 (41,768 responses; 19.1%), it has remained relatively constant recently. In fiscal year (FY) 2014, we received 65,828 responses from 519,155 surveys sent, for a response rate of 12.6%. The response rate was the same in FY 2013 (58,693 responses from 467,394 surveys sent). The absolute number of responses we received, however, exceeded most benchmarks. For example, HCAHPS requires only 300 responses per year per hospital.

Parallel improvements in quality, risk management, and employee satisfaction

Despite concerns to the contrary, neither the quality nor the cost of care has suffered over the course of the EPE initiative. In fact, improvements in these areas have occurred alongside the improvements in patient satisfaction. In 2010, the University of Utah Health Care system was ranked number 1 in quality in the nation by the University HealthSystem Consortium, out of more than 118 academic medical centers, and recorded continuously increasing absolute scores for quality and safety over the study period. (The University HealthSystem Consortium performance metrics continue to evolve—in 2014, they included mortality, effectiveness, safety, equity, HCAHPS, and efficiency.) For the last six years, our health system has consistently ranked in the top 10 in this cohort. At the same time, our average total facility expenses per case-mix-index-adjusted discharge decreased by 0.5% between 2007 and 2013, compared with an average increase of 2.9% across all University HealthSystem Consortium members over the same period.

With improved patient satisfaction has come a lower rate of malpractice litigation.15 Malpractice premiums declined from $10.7 million in 2007 to $7.3 million in 2012, despite a significant increase in the number of physicians practicing and a more than 40% increase in professional revenue. This rate of decline in our malpractice premiums exceeded national trends.16

Finally, we saw increases in employee satisfaction as well as in patient satisfaction. Responses to recent internal surveys rank quality of care, teamwork, and likelihood to recommend facility among the highest-scoring factors. Most notably, both the School of Medicine and the University Hospitals and Clinics received an average score of 84 out of 100 with regard to “staff’s concern for and interest in their patients,” a score of 85 with regard to “likelihood you would recommend this facility to friends and family for care,” and a score of 85 with regard to “overall quality of care at this facility.”

Unanticipated benefits

Unexpected benefits of posting patient reviews on our Web site have included sharp increases in our Web traffic and improved search engine optimization. In February 2013, Google began indexing the provider profiles, including the five star ratings. In March 2014, the profile pages received 122,072 views, a large increase from the 75,970 views they received in March 2013. Additionally, in a separate patient survey, respondents ranked “patient satisfaction ratings and comments” as the second most important feature of the provider profiles, second only to “specialty focus.” The provider profiles and patient rankings and comments appear at or near the top of most major search engine results when users search for a specific provider, which providers have come to value.

Improving Patient Satisfaction and the Value of Care

Despite accounting for almost one-fifth of the U.S. economy, health care has generally received poor patient satisfaction ratings. Some studies have suggested that an overemphasis on patient satisfaction can be detrimental to providing good health care and to fostering good health.2–5 These studies cite correlations between high patient satisfaction ratings and higher overall health and prescription drug expenditures, higher inpatient care utilization rates, and increased mortality. They also posit that patient satisfaction is just a poor measure of quality of care. Similarly, others have expressed concerns that patient experience initiatives place physicians at the mercy of unreasonable patient demands, including narcotic-seeking behavior.17,18

In contrast, recent meta-analyses and reviews have shown that high patient satisfaction correlates with improved outcomes.3,4,7 Thus, how the “exceptional patient experience” is defined and how the data assessing it are collected are critical. Manary et al10 have suggested that more positive correlations between patient satisfaction and quality or outcomes are found when the survey is (1) related to a specific event or episode of care (rather than related to general impressions of a plan or provider); (2) timely (within days, not months); and (3) focused on the patient–provider relationship. All of these characteristics were part of our EPE initiative. Response rate also can impact the validity of the survey. Although our response rate declined from 19.1% the first year to 12.6% the next two years, we did receive over 65,000 responses in 2014.

Patient engagement initiatives should focus on empathy, communication, trust, and accessibility (see List 1). These factors affect the types of care that Otani et al9 identified as contributing to patient satisfaction: staff care, nursing care, and physician care. While the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care remains unclear, measures of patient satisfaction increasingly are factored into physician reimbursement models. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began using HCAHPS ratings to calculate physician payments in 2015. The HCAHPS questions tend to assess the process of delivering care, communication, and engagement in health care decisions, similar to the survey questions we used.19

Making patient satisfaction data available also has helped to address the growing desire among patients for more information about their providers. A 2012 Local Consumer Review Survey showed that 85% of consumers used the Internet for information on local businesses and that 72% trusted Web reviews as much as personal recommendations, provided there were multiple reviews and the reviews appeared to be authentic.20 A separate Price Waterhouse Cooper study showed that 42% of consumers used social media to access reviews of physicians or treatments.21 These numbers are only going to grow. Moreover, the data that health care systems collect from their patients are seen as more valid than those collected through public physician rating systems.3,22

The challenges that the University of Utah Health Care system faces with regard to patient satisfaction are common in health care, and the approaches to improving the patient experience that we have described here are likely adaptable to other institutions. Several other health systems in the United States also have posted patient satisfaction scores online. Among the first worldwide to take this approach was the National Health Service in 2008. Our results are consistent with theirs—over a two-year period from 2009 to 2010, based on 10,274 Web-based ratings, patient satisfaction correlated positively with outcomes measurements (lower mortality and lower readmission rates).3

The Virtuous Cycle of Patient and Physician Engagement

Driven primarily by data transparency, peer-to-peer competition, and the sharing of best practices at the system and provider levels, our EPE initiative has created a virtuous cycle. Stronger relationships between patients and providers have enhanced the engagement and satisfaction of both groups. In addition, by training future providers in this environment, we can ensure that this culture of outstanding service, as well as of quality and safety, will continue in the future.

In conclusion, what began as a patient satisfaction initiative evolved into a model for physician engagement, values-based employment practices, enhanced professionalism and communication, reduced variability in performance, and improved alignment of the mission and vision across hospital and faculty group practice teams. This system-wide shift to patient-centered care sets the stage for broader health system delivery transformation.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Danielle Sample, Joe Borgenicht, and Kirsten Stewart in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Previous presentations: Betz AL. Courage. Address of the chair of the Board of Directors of the Association of American Medical Colleges. Presented at: Learn Serve Lead 2014: The AAMC Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL; November 8, 2014.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greaves F, Pape UJ, King D, et al. Associations between Web-based patient ratings and objective measures of hospital quality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:435–436. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: A national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405–411. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaac T, Zaslavsky AM, Cleary PD, Landon BE. The relationship between patients’ perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1024–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: The evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:111–123. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyu H, Wick EC, Housman M, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Patient satisfaction as a possible indicator of quality surgical care. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:362–367. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otani K, Waterman B, Faulkner KM, Boslaugh S, Burroughs TE, Dunagan WC. Patient satisfaction: Focusing on “excellent.”. J Healthc Manag. 2009;54:93–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:201–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1211775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elwyn G, Buetow S, Hibbard J, Wensing M. Measuring quality through performance. Respecting the subjective: Quality measurement from the patient’s perspective. BMJ. 2007;335:1021–1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39339.490301.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacon N. Will doctor rating sites improve standards of care? Yes. BMJ. 2009;338:b1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCartney M. Will doctor rating sites improve the quality of care? No. BMJ. 2009;338:b1033. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston CB. Patient satisfaction and its discontents. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:2025–2026. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, Miller CS, Gauld-Jaeger J, Bost P. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287:2951–2957. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker BJ, Mitchell CW. Third quarter financial results for medical professional liability writers, expectations for year-end results. Med Liabil Monit. 2014;39:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zgierska A, Miller M, Rabago D. Patient satisfaction, prescription drug abuse, and potential unintended consequences. JAMA. 2012;307:1377–1378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brett AS, McCullough LB. Addressing requests by patients for nonbeneficial interventions. JAMA. 2012;307:149–150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Members of the ACEP Emergency Medicine Practice Committee. Emergency department patient satisfaction surveys. An information paper. June 2011. http://www.acep.org/patientsatisfaction/. Accessed September 29, 2015.

- 20.Anderson M. Study: 72% of consumers trust online reviews as much as personal recommendations. Search Engine Land. March 12, 2012. http://searchengineland.com/study-72-of-consumers-trust-online-reviews-as-much-as-personal-recommendations-114152. Accessed September 29, 2015.

- 21.Price Waterhouse Cooper Health Research Institute. Social media “likes” healthcare: From marketing to social business. 2012. http://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/publications/health-care-social-media.jhtml. Accessed September 29, 2015.

- 22.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. JAMA. 2014;311:734–735. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]