Abstract

Purpose

Despite widespread implementation of policies to address mistreatment, high rates of mistreatment during clinical training are reported, prompting the question of whether “mistreatment” means more to students than delineated in official codes of conduct. Understanding “mistreatment” from students’ perspective and as it relates to the learning environment is needed before effective interventions can be implemented.

Method

The authors conducted focus groups with final-year medical students at McGill University Faculty of Medicine in 2012. Participants were asked to characterize “suboptimal learning experience” and “mistreatment.” Transcripts were analyzed via inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Forty-one of 174 eligible students participated in six focus groups. Students described “mistreatment” as lack of respect or attack directed toward the person, and “suboptimal learning experience” as that which compromised their learning. Differing perceptions emerged as students debated whether “mistreatment” can be applied to negative learning environments as well as isolated incidents of mistreatment even though some experiences fell outside of the “official” label as per institutional policies. Whether students perceived “mistreatment” versus a “suboptimal learning experience” in negative environments appeared to be influenced by several key factors. A concept map integrating these ideas is presented.

Conclusions

How students perceived negative situations during training appears to be a complex process. When medical students say “mistreatment,” they may be referring to a spectrum, with incident-based mistreatment on one end and learning-environment-based mistreatment on the other. Multiple factors influenced how students perceived an environment-based negative situation and may provide strategies to improving the learning environment.

Despite promising efforts, student mistreatment remains an ongoing challenge in medical education, with published studies continuing to report high rates of mistreatment since this issue first gained recognition in the 1980s.1–13 The mere fact of perceiving mistreatment during medical training has serious implications for the individual student; studies have shown higher rates of loss of confidence, decreased work satisfaction, depression, substance abuse, and suicidal thoughts in students who feel mistreated.14–16

Studies have explored many dimensions of mistreatment: “belittlement” and “public humiliation,” intimidation and power mistreatment, sexual harassment, ethnic and racial discrimination, and physical abuse. Many schools have responded by implementing policies to address mistreatment directly. Despite this, surprisingly, the perception that mistreatment occurs remains frequent.17 This suggests that we may be overlooking important aspects of mistreatment, which require further elucidation in order to address the problem fully.

How Does Mistreatment Relate to the Learning Environment?

The literature on mistreatment focuses on the individuals involved and frames the concept of mistreatment as an act perpetrated by someone, perceived by someone else. Although individual factors were predominant in their study, as Rees and Monrouxe18 point out, the complex interactions between individuals and the environment may contribute to the perception of mistreatment. They cite organizational psychology literature that supports the idea that when a student perceives mistreatment, he or she does so in a context with many variables: the work organizational structure, the specifics of the work involved, the “perpetrators” and their preexisting characteristics, as well as the students’ own preexisting characteristics. To date, there has been little exploration of the perceptions of mistreatment as it relates to the learning environment in the health professional setting. Does the perceived organizational structure and work environment influence how medical students perceive mistreatment? Are there learning experiences that contribute to or mitigate how students may view a situation as mistreatment or not?

Does Mistreatment Mean More Than We Think?

Another important aspect is whether mistreatment that is deemed “official” truly encompasses all situations in which trainees may feel mistreated. In studies, the majority of mistreatment incidents students reported in the surveys were not officially reported.17 In one study, the incident not being deemed as severe enough was cited by residents as the top reason to not report sexual harassment.19 It is plausible to imagine that mistreatment that may not be considered “official” enough for students to report to the teaching institution may still lead to significant distress for the student involved. Are there other types of perceived mistreatment that have not been clearly studied, which contribute to the high levels of mistreatment reported by trainees? What do students mean when they use the term “mistreatment”?

An exploration of how students perceive mistreatment as it relates to the learning environment, whether other aspects of mistreatment could be elucidated, and a definition of “mistreatment” from the students’ perspective could positively inform the literature on how to better address the resistant issue of mistreatment. Students’ insights might help in the design of effective interventions and also may help clinical teachers to better guide students who must navigate the complex “emotional waters” of learning medicine in the clinical context.

We therefore aimed to explore how students perceive mistreatment in the context of the learning environment, especially when it is “suboptimal,” and the range of what students mean when they use the word “mistreatment.”

Method

Study design

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study using focus group interviews. This methodology was chosen in an effort to capture participants’ perspectives as they considered their views while interacting with others.

We recruited a convenience sample of final-year medical students in the 2012 cohort at McGill University Faculty of Medicine from February to March 2012. Following ethics approval by the McGill institutional review board, we invited all 174 final-year students to participate, using announcements during teaching sessions, e-mails, and postings on notice boards in the lecture halls at the medical school. Students signed up for a focus group session at a time convenient for them during this one-month period. We planned to conduct focus groups until theoretical saturation of the data, which we had anticipated to occur after three to four focus groups. So as not to bias students, we introduced the study as aiming to obtain student perspectives about “the learning environment” rather than explicitly about “mistreatment.” We required participants to read and sign a consent form before participation.

We moderated a series of one-hour audio-recorded focus groups (R.G. for five focus groups and L.S. for one focus group). We used a semistructured interview technique with an interview guide20 and open-ended questions to explore two main questions21: What do you perceive as suboptimal learning experience (SoLE); and what does “mistreatment” mean to you? We included interview probes which were used if needed to encourage students to further compare and contrast different elements of mistreatment and suboptimal learning experiences.

We administered a written questionnaire after the sessions to ask students their age, sex, intended discipline, and their personal experience with “SoLE” and “mistreatment.” We also asked students to comment in writing how they perceived “SoLE” and “mistreatment” to allow individual participants to voice opinions that they may not have wanted to share in the focus group setting. This questionnaire also asked students if they had felt comfortable sharing their views with their peers during the focus group.

Data analysis

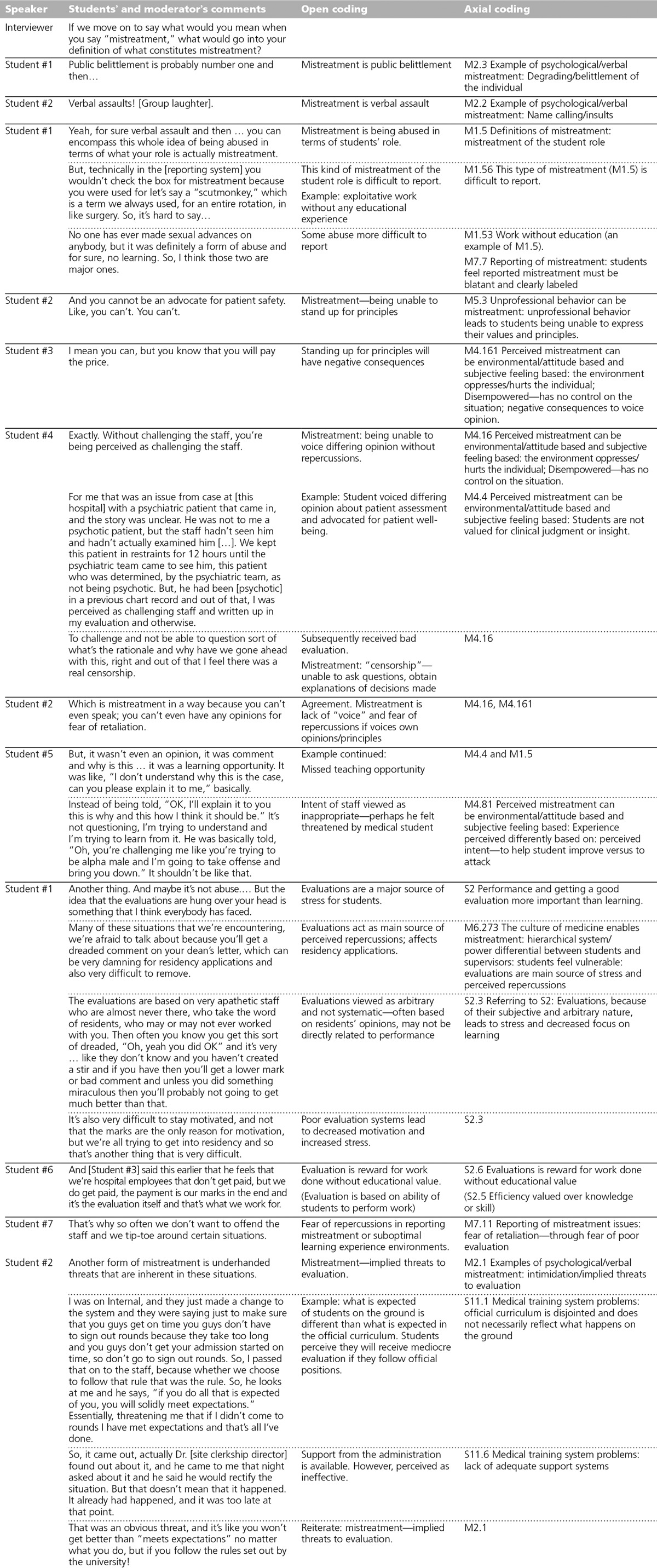

We transcribed audio recordings without identifying students and anonymized identifying information in instances of “mistreatment” by removing any mentioned names of individuals involved and location information. The data analysis process began with both of us reading all transcripts, which facilitated initial development of framework concepts and categories. We then exhaustively coded the transcripts using inductive thematic analysis with several levels of coding.21–23 We systematically examined convergence and divergence in the data at each level of coding. We organized the variations of the convergence and divergence into categories of smaller groups of categories. We worked in a series of cycles to obtain ever more abstract frameworks. An example of the first two levels of coding is included in Appendix 1. The first-order thematic analysis was conducted completely by R.G. and partially by L.S. for interrater reliability. Higher-order themes and framework were developed jointly through regular meetings. The few discrepancies were minor; when they occurred, they were resolved via discussion with reference to specific instances in transcripts if needed to reach consensus.

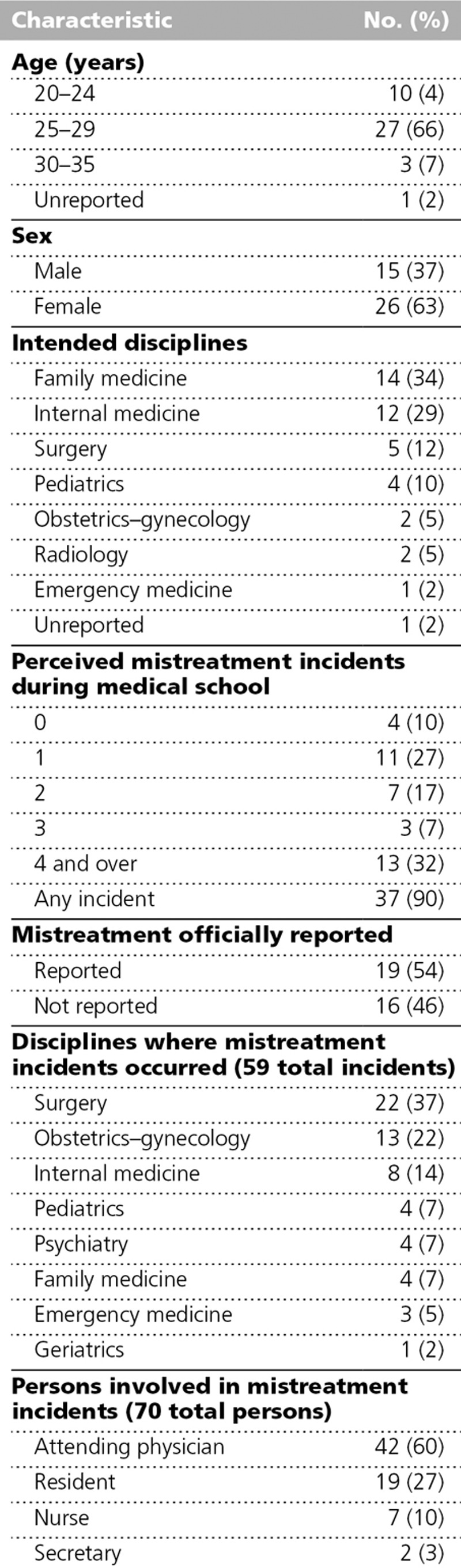

Table 1.

Characteristics of 41 Participating Medical Students and Their Experiences With Mistreatment and Suboptimal Learning Environments, McGill University Faculty of Medicine, 2012

As the central discussion in all focus group sessions revolved around the comparison and contrast of different degrees of mistreatment within the learning environment, we deemed the use of a spectrum the most appropriate framework to represent the categories obtained from the data analysis. This concept was thought to accurately reflect the raw data, where students themselves often used terms such as “spectrum” and “blurry” to describe mistreatment. We present the data subsequently using this framework of spectra of mistreatment and SoLE as they relate to each other.

We compiled the small quantitative section of the post-focus-group session questionnaire results to determine the characteristics of the participants. The qualitative narratives from the questionnaire were transcribed and coded in a similar fashion to the focus group data. We then assessed these written narratives for divergence and convergence compared with the focus group session transcripts.

Results

We conducted six focus groups with a total of 41 of 174 eligible participants (Table 1). We conducted more focus groups than anticipated because there was higher-than-expected interest among students, and we elected not to cancel any time slots for which students had signed up. Thirty-seven of the 41 students (90%) reported having felt mistreated, with the vast majority of these incidents occurring during the clinical years. Only 19 (54%) participants who had felt mistreated ever officially reported an incident to the administration.

Focus group discussions included multiple personal narratives (see example in Appendix 1). When mistreatment was discussed, the narratives were rich and emotionally charged. Students shared personal stories that had profound impacts on their training experience, perception of medicine, and personal life. These stories were sometimes shocking to both peers and moderators.

Although students agreed about many aspects of SoLE and mistreatment, they also commonly expressed diverging opinions, especially about their definitions of what could constitute mistreatment within the learning environment. These debates provided powerful sources of understanding on what influences the perception of mistreatment.

The responses from the qualitative section of the post-focus-group questionnaire did not diverge significantly from the focus group session discussions. Students most often reiterated what was discussed during the session. No student reported feeling uncomfortable expressing their views in the focus groups.

In the following sections, we have included students’ quotes from the focus groups to illustrate major themes. We have lightly edited the quotes so that they are more readable, but we have not changed their style or meaning.

Where there is consensus

Students agreed with each other that the concept of SoLE can be seen as situations where learning is compromised. Students identified two major types of SoLE that they commonly experienced: when learning is not the main objective, using terms such as “work without education”; and when the learner is distracted from learning by circumstances, such as psychological pressure to perform, sleep deprivation, or mistreatment.

Students agreed that the major components of “mistreatment” were lack of respect or attack directed at the person. Although lack of respect may have involved name-calling or “public humiliation,” subtle incidents such as repeated lack of courtesy were also considered as potential mistreatment. Some students also included feeling disrespected as future colleagues as mistreatment; examples ranged from students feeling their assessment of patients were dismissed to more dramatic situations—for instance, being coerced to participate in what they considered to be unprofessional behavior such as forging prescriptions or making fun of patients.

Students described attacks directed toward the person to include insults, comments that degraded or belittled, criticisms about students’ personality, sexual or racial comments, or physical attacks. Participants tended to agree that incidents of this sort are mistreatment; however, many stated that this degree of mistreatment was rare.

Differing perspectives

More controversially among students, some voiced feeling mistreated when they were “disrespected” in their role as students. This usually consisted of situations where they felt they were performing work without perceived appropriate supervision or adequate learning opportunities. They labeled the environment as “exploitative.” This is an example of where differing perspectives emerged. These differences in perspectives and subsequent debate among the participants provided an important understanding of “mistreatment” within the learning environment. In all focus groups, students spontaneously stated that mistreatment and SoLE are difficult to define and that the terms are subject to interpretation based on individual and environmental factors.

Some students argued that mistreatment should be defined as broadly as possible, in order to capture the widest range of situations in which students may feel “mistreated,” with significant overlap with the definitions of SoLE. Others believed that “mistreatment” should be applied only to situations where a clear lapse of conduct has occurred. One such exchange occurred as follows:

Student 1: I find mistreatment to be more in the blatant sense of the term, like verbal or some sort of comment or something that’s made. Obviously, it’s a spectrum, but I have to say despite having some very similar experiences where there are times that you feel very overwhelmed and someone treats you in a specific way and you feel like you want to swell up in tears. At the same time, I’ve never written on my evaluation form of any elective or rotation that I’ve been mistreated.

Student 2: But I feel like when we take that definition, then we’re ignoring a very systematic and wide range of how we are being mistreated. If I take my recent rotation, nobody said anything that I could label as mistreatment on my evaluation form.… But, every day, I just felt that I had a lot of disrespect from my residents, that they would demean me in many, many ways, in terms of both a woman that was working there but also a medical student.… There was a daily grind in which I felt disrespected and demeaned in every single thing that I said, in any management options, or every time I would try to do something for a patient—they would dismiss me. So, in a way, it doesn’t go into a definition of mistreatment or a blatant definition.

These types of discussions occurred in five of six focus groups. Students tried to find common ground by agreeing that some mistreatment was different than “blatant” mistreatment but still had significant impact.

Emergence of themes: A framework of where mistreatment meets SoLE

A phenomenon emerged in which some students perceived mistreatment when the situation is not necessarily considered to be mistreatment by all. This type of mistreatment usually occurred in a specific learning context as a result of the organizational environment. This dichotomy of perspectives led to the most debate. The following framework summarized the focus group discussions.

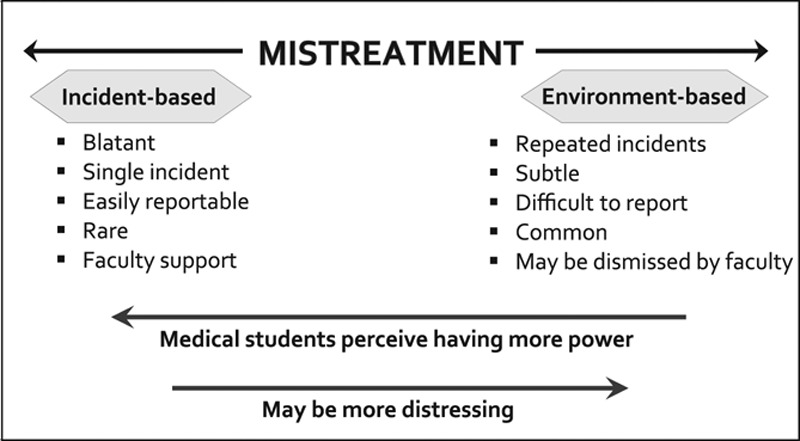

The spectrum of mistreatment

At one end of the spectrum, as shown in Figure 1, mistreatment was described as a single incident that was blatant—for instance, a verbal insult, physical abuse, or unwanted sexual contact. Because incidents of this type “blatantly” violated the code of conduct, they were easily reported. Students felt that good faculty support existed to reduce this type of mistreatment. Although we heard examples, students perceived them as rare incidents. This type of behavior was invariably labeled by all as mistreatment.

Figure 1.

How students perceive mistreatment along a spectrum. Concept map derived from a study of 41 final-year medical students, McGill University Faculty of Medicine, 2012.

In contrast, students in all focus groups described perceived mistreatment based on an “environment” or attitude, such as a subjective feeling of being disrespected within a certain learning environment. The incidents were subtle and may not be considered as “official” mistreatment when taken in isolation. However, repeated incidents led to the learning environment being perceived to be “systematic mistreatment.” To use one student’s words:

The difficulty is that on our evaluation form, it asks “Have you been mistreated?” And our university has these definitions of what mistreatment is, but a lot of the times what I feel that I can’t really say, “OK, there’s been one thing that makes me feel mistreated.” It’s that every day, I don’t want to go to work sometimes, and at the end of the day, I feel really bad about myself. I feel like “What am I doing here?” and sometimes I get home and I cry. Somehow I can’t say that one person did something specific, but I feel that I’m working in an environment that is so detrimental to who I am and why I even wanted to go into medical school in the first place.… That works against me, and I’m swimming against the current.

Although this type of perceived mistreatment, which relates directly to the learning environment, may have had tremendous impact on the student as illustrated above, it was difficult to report because it rarely fell under the usual label of “mistreatment” as defined by institutional policy. As a result, students perceived poor faculty support with regards to such “environment-based” mistreatment. Other examples include when students were expected to perform noneducational work in a hostile environment, an atmosphere where students of one gender felt discriminated against, or when students felt their contributions were not valued.

I mean getting up before the sun comes up and leaving the hospital when the sun is already down, you know, is already hard enough. And knowing that you’re going to get yelled at by a bunch of residents or staff because you forgot where Mr. C moved to on rounds or whatever is just not cool, it’s like borderline depressing to do that.

Because this was not universally agreed on as “mistreatment” by the institution and faculty members and even other students, those who perceived they were victims tended to feel powerless. Students used strong language such as “having no voice” and “living in constant fear” to express their distress:

The thing that hurts the learning experience here and that results in a sense of mistreatment here is more a sense of disempowerment and disenfranchisement and vulnerability and the inability to respond to unjust evaluation or to a resident who’s just an asshole.

Because of the lack of recourse to report the experience, students appeared to find “environment-based” perceived mistreatment to be even more distressing than “blatant” incidents where they easily obtained faculty support.

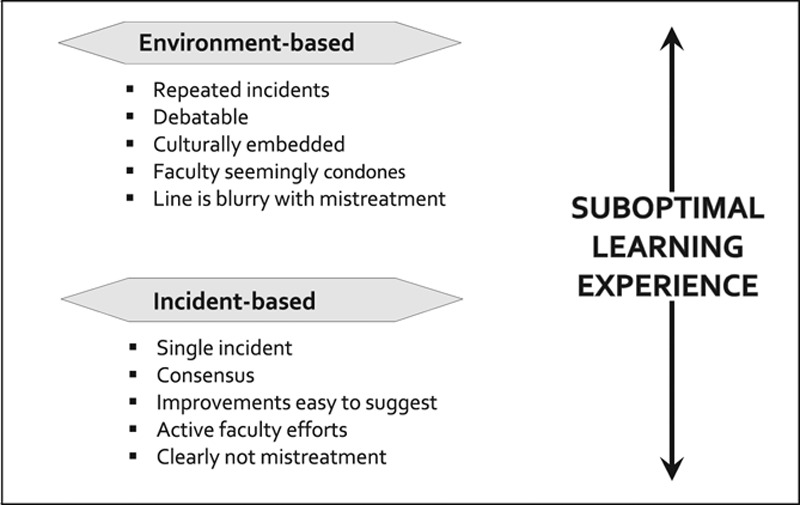

The spectrum of SoLE

SoLE was viewed as sharing similar characteristics. On one end of the spectrum, as shown in Figure 2, were single incidents that all parties recognized as needing improvement, such as lack of an orientation or a poor lecture. On the other end were repeated incidents that led to students perceiving the environment as not respecting their role as learners. In this type of environment, students perceived that work is more valued than learning, patient care, and intrinsic competencies other than medical expertise.24 They may have felt that the assessments of their performance were overemphasized. Other examples included “inappropriately” high expectations, excessive workload, and environments that do not promote students’ learning as a priority.

Figure 2.

How students perceive suboptimal learning experience along a spectrum. Concept map derived from a study of 41 final-year medical students, McGill University Faculty of Medicine, 2012.

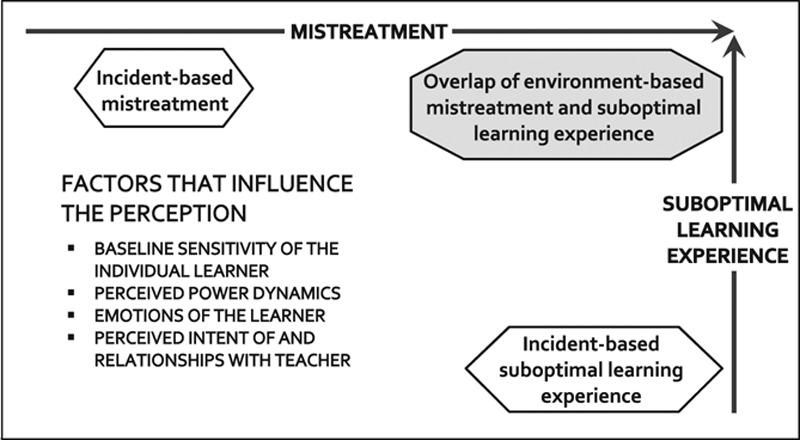

The meeting of mistreatment and SoLE and factors that influenced perceptions

Mistreatment based on an isolated incident, such as being called “stupid,” was clearly distinct from SoLE based on one incident, such as a poor lecture. In Figure 3, they are shown at right angles from each other, which depicts a framework for understanding the relationship between mistreatment and SoLE. However, environments or repeated incidents where students could have perceived mistreatment or SoLE often overlapped within the learning context. Whether a student perceived mistreatment rather than SoLE within this framework appeared to be influenced by a complex interplay of factors.

Figure 3.

Where mistreatment and suboptimal learning experiences overlap in student perceptions of mistreatment. Concept map derived from a study of 41 final-year medical students, McGill University Faculty of Medicine, 2012.

Students demonstrated impressive insight in identifying elements that influenced their own perceptions of mistreatment. Four major factors emerged and appeared to have modified the way they perceived negative situations. Students suggested that addressing these factors may enhance their learning process.

Baseline sensitivity: “How personally one takes it.” In three of the five focus groups where the debate occurred, participants recognized that students may be more or less likely to interpret a situation as mistreatment because of their personality or background. Whereas some students felt that there was nothing to be done about differing sensitivities, other students suggested that teachers in clinical environments should be trained to be sensitive to learners with differing thresholds for perceiving mistreatment.

I’ve personally came from [a background] where I was used to being physically and verbally assaulted, so I kind of have a very high threshold in the level of back and forth I would take. But, I’ve seen some levels, where not to me personally, when I’ve seen staff interacting with people and other students in a demeaning way. And I’m like, yeah, I know how this person responds, and this is not an appropriate thing to say to this person.

Perceived power dynamics: Empowerment versus “culture of fear.” Empowerment was a common thread in all six focus groups. Students proposed that a culture of empowerment was important for their sense of personal integrity and well-being; some students even forwarded that they would be less likely to react negatively to situations which could be perceived as mistreatment if they felt empowered.

In contrast, students felt that the organizational culture of medicine is tolerant of situations which could be construed as mistreatment. When they felt unable to express their views or to behave in a way that reflected their principles, they felt that there was a “loss of sense of self” in the learning context. As a result, they had a heightened sense of vulnerability, often accompanied by anger and resentment:

If you’re in a situation that you feel is a bad situation and you don’t have the power to change it, that could be very destructive. I think that’s what ends up being an issue here. I don’t think [our school] has mistreatment with a capital “M” problem. I’ve never seen a surgeon throw a scalpel at someone, I’ve never been punched, I’ve never been hurt or sexually harassed.… The thing I think that corrodes people over the year and a half of clerkship is the sense that when they run into stuff that is bad, they can’t change it or the faculty isn’t behind them to change it.… That lack of power to students and lack of involvement of students in the decision making process and the lack of voice for students in the faculty is actually a huge problem.

Emotions of the learner: “Trauma of medical training.” Students discussed at length the difficulties of clinical training that affect the way they perceived the experiences: long hours, sleep deprivation, feeling isolated, changing environments and expectations, and even simple things such as not having a place to put their belongings. These work-related difficulties appeared to amplify how negatively students perceived their environment, making them more sensitive to perceiving mistreatment.

It’s not recognized the psychological and emotional impact that this training has on us. I think that in some points we may be hypersensitive and some things that we interpret as mistreatment may not be, but it really, really feels that way.

Perceived intent of and relationship with the teachers. Teachers played an important role in the learning experience. In four focus groups, student conveyed the view that “mistreatment” often occurred when poor communication occurred between teacher and student. Students expressed wanting to have relationships with their teachers where they would be able to discuss the issue openly if they felt mistreated. Even if a negative experience were to occur, if the relationship could permit communication about the situation, then the perception of the experience would be more positive.

In most cases, it’s issues with communication that didn’t get across that the intentions were clear or the staff and students.… I mean, physical assault and the extreme cases, I don’t think happen very often.… For the most part, it’s usually things that are kind of on the line and not feeling good about myself and feeling small, but maybe if I talked about it to my staff, maybe it wouldn’t be perceived as so bad or as mistreatment.

Students were very sensitive to the perceived intent of their teachers. If the behavior appeared to be motivated by what is considered important, such as patient care, the behavior was construed more positively than if it was perceived to be motivated by personal gain.

I think there’s an element of intention. If [the teachers] say, “Look, it’s very busy, but we’ll have time later to have some element of teaching. Try and get through this,” it’s very different from saying, “go and do a stack of discharge summaries,” and screw teaching. It’s a difference of mentality and intention.

The other side of the story: When negative experiences may be seen as “positive”

Whereas the majority of discussions involved how students were negatively affected by mistreatment, a minority of students voiced the view that difficult and stressful situations can lead to students being more capable and resilient:

Any kind of situation will build character. So you can always consider that to be a positive point and say that “I can push the helm” and we’ll come up these really resilient beings. I think the ends justify the means there.

Furthermore, despite 90% of our participants reporting feeling mistreated in the post-focus-group questionnaire, students in most focus groups invariably stated that they believed the training prepared them well for residency and practice.

Discussion

Our study confirms that how students perceived negative situations within the learning environment appears to be a complex process. When medical students say “mistreatment,” they may be referring to a spectrum, with incident-based mistreatment on one end and environment-based mistreatment on the other. There are in fact a large number of experiences that students may label as “mistreatment” that relates to the learning environment, and these experiences fall outside of the usual label of “official” mistreatment used in institutional policies. Multiple factors influenced whether students perceived such a negative situation in the learning environment as mistreatment or purely as SoLE without the resulting emotional implications of “mistreatment.”

Despite rates of student mistreatment cited as high as 80% to 90%,12,13,19,25–28 there is voiced resistance to change. For example, some have expressed the view that “intimidation” may be good, to motivate students to study, and may even protect patients.29 In our focus groups, our students reported hearing faculty members question whether they were “too sensitive” when discussing mistreatment. Others still may be tempted to suggest that these numbers reflect that today’s students feel more entitled and less committed to the profession. One study found that both teachers and students may view “mistreatment” as potentially educational,30 a view which was also expressed by some of our participants.

However, although some of these arguments may be valid, the perception of mistreatment during training appears to be overall detrimental to the well-being of both the individual and the profession. Studies have shown that feeling mistreated is unlikely to make trainees more motivated to learn, more inclined to work longer hours, or more caring towards patients, and in fact has quite the opposite effect.16,31 Although one study showed that one-quarter of students who felt “humiliated” reported feeling more motivated, 60% of them avoided the department and persons involved, and 16% considered quitting medicine.16 A negative perception of the training process also risks corroding medical students’ sense of altruism, empathy, and enthusiasm for the profession16; one study directly correlates feeling mistreated to students reporting that they had mistreated patients.31 This is alarming because attitudes acquired during training may influence values of the future physician.

Although it is possible that some students may feel more “resilient” and derive educational value from being in a negative environment, this potential “benefit” may not be worth the risks and negative consequences. We argue therefore that there is great incentive for change. As efforts to implement better institutional policies with an improved reporting system and strict codes of conduct continue, the results of this present study suggest additional avenues that involve modifying factors which influence perceptions. In our study, students identified baseline sensitivity, sense of empowerment, emotional response to challenges of medical training, and relationships with teachers as being important. These are in fact psychological needs that are readily acknowledged as important by our society.32 Student empowerment has been long recognized by educators as important in the learning process.33–35 Empowered students are more involved, motivated, and committed to the learning process. Students also wanted more support during training; suffering, loss, and helplessness in the face of incurable illness can be difficult to handle for the idealistic medical student, and he or she understandably undergoes personal stress when starting clinical training. In these challenging circumstances, students also valued their relationship with teachers and mentors, and poor communication between teacher and student affected students’ well-being.

Examples of strategies might include formalized and ongoing involvement of students in curriculum design, sensitization about issues of mistreatment for both faculty and students to improve students’ sense of empowerment, development of stronger support networks and resources, creation of multiple avenues for medical students to reflect on and share their experiences, and formal educational curricula on improving communication skills of both learners and teachers.

Finally, we were alarmed and surprised by the amount and degree of unprofessionalism and outright mistreatment incidents described by our participants in the context of a concerted effort by this institution to improve the learning environment. It is relevant to note that our university had implemented a series of efforts to target mistreatment over the last 10 years, including establishing a code of conduct, implementing a clear algorithm for both direct and anonymous reporting of incidents, and campaigning to increase awareness for both faculty and students on the issue of mistreatment. Despite this, graduating students, at least the 25% who attended our focus groups, continued to perceive mistreatment as prevalent over the course of their training. This has been reported elsewhere,17 suggesting that there is still much work to be done. “Blatant” mistreatment still occurs, even after decades of efforts at many institutions, including ours.

Our study is limited in that it is based on a single cohort of medical students. However, this was an exploratory study, for which multiple cohorts may not be necessary. Given the limited time students had to participate in the focus groups, we did not explore in-depth mistreatment related to gender or specialties, which have been frequently considered in other studies. Although triangulation may have been possible, we did not believe it was necessary as our study was focused on exploring the perspectives of students who were affected by perceived mistreatment. Finally, despite our attempt at limiting recruitment bias by advertising the study as being about the “learning environment,” participants may have been more interested in and more likely to have perceived mistreatment than nonparticipants. However, the experience of our participants resembled reports from schools across the world in both frequency and types of experiences. The students in our study represented the distribution of the graduating medical class in terms of age and career choices (Table 1). The same issues have been raised at other institutions.3,12,13,16,18,19,25–30,36,37 We believe therefore that the findings are generalizable to clinical training in other schools.

Our study takes a novel approach to understanding the phenomenon of student mistreatment during clinical training, and, to our knowledge, it is the first study of its kind. We conducted more focus groups than needed to attain theoretical saturation, and the number of participants constituted a quarter of the graduating class, giving us a wide range of perspectives and experiences. Our study has yielded new information about this field, and this is the first time the students’ perspective on what “mistreatment” means as it relates to the learning environment is explored. The implication of this study goes beyond definitions: Further research to explore the difference in perception of “mistreatment” between learners and teachers may suggest strategies to mitigate the perception of mistreatment and thus improve the learning experience.

The perception of mistreatment in the learning environment is a complex process, with a spectrum of “mistreatment” occurring outside of the official institutional policies. Our findings may help educators and clinical teachers to better understand students’ perspectives when they report mistreatment. In addition to establishing clear guidelines and systems to target mistreatment once it has occurred, medical schools should also undertake interventions that alter perceived power dynamics, improve how medical students cope with the training experience, and focus on communication skills as supplemental strategies to improving the perception of the learning environment.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank foremost the participating students for sharing their experiences so candidly in a supportive and collegial atmosphere. The authors also thank Drs. Richard Cruess and Sylvia Cruess for their mentorship and thoughtful comments, Dr. Peter Nugas for providing methodological advice, Dr. Peter McLeod for his helpful comments on a draft of this paper, Drs. Noémie Savard, Inas Malaty, and Dr. Ning-Zi Sun for acting as assistant focus group moderators, and the members at the Centre for Medical Education for their invaluable input and comments.

Appendix 1

Edited Five-Minute Section of a Focus Group Interview, With an Example of Coding, From a Study of 41 Final-Year Medical Students’ Perceptions of Mistreatment, McGill University Faculty of Medicine, 2012

Footnotes

Funding/Support: Centre for Medical Education, McGill University, for transcription of focus group recordings.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of the Faculty of Medicine, McGill University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

References

- 1.Cheema S, Ahmad K, Giri SK, Kaliaperumal VK, Naqvi SA. Bullying of junior doctors prevails in Irish health system: A bitter reality. Ir Med J. 2005;98:274–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elnicki DM, Curry RH, Fagan M, et al. Medical students’ perspectives on and responses to abuse during the internal medicine clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14:92–97. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassebaum DG, Cutler ER. On the culture of student abuse in medical school. Acad Med. 1998;73:1149–1158. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lytle GH, Holmes JE, Olsen MC. Medical student abuse: A review of the literature and experience on one campus. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1993;86:613–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maida AM, Vásquez A, Herskovic V, et al. A report on student abuse during medical training. Med Teach. 2003;25:497–501. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001606317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maida AM, Herskovic MV, Pereira SA, Salinas-Fernández L, Esquivel CC. Perception of abuse among medical students of the University of Chile [in Spanish]. Rev Med Chil. 2006;134:1516–1523. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872006001200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagata-Kobayashi S, Sekimoto M, Koyama H, et al. Medical student abuse during clinical clerkships in Japan. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nora LM, McLaughlin MA, Fosson SE, et al. Gender discrimination and sexual harassment in medical education: Perspectives gained by a 14-school study. Acad Med. 2002;77(12 pt 1):1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200212000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson DA, Becker M, Frank RR, Sokol RJ. Assessing medical students’ perceptions of mistreatment in their second and third years. Acad Med. 1997;72:728–730. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199708000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhari M, Kokkonen J, Nuutinen M, et al. Medical student abuse: An international phenomenon. JAMA. 1994;271:1049–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.13.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanlneveld CHM, Cook DJ, Kane SLC, King D. Discrimination and abuse in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:401–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02600186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR. Do residents also feel “abused”? Perceived mistreatment during internship. Acad Med. 1997;72(10 suppl 1):S51–S53. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199710001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR, Eckenfels EJ. Student perceptions of mistreatment and harassment during medical school: A survey of ten United States schools. West J Med. 1991;155:140–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richman JA, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM, Christensen ML. Mental health consequences and correlates of reported medical student abuse. JAMA. 1992;267:692–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuchert MK. The relationship between verbal abuse of medical students and their confidence in their clinical abilities. Acad Med. 1998;73:907–909. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199808000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkinson TJ, Gill DJ, Fitzjohn J, Palmer CL, Mulder RT. The impact on students of adverse experiences during medical school. Med Teach. 2006;28:129–135. doi: 10.1080/01421590600607195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: A longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. “A morning since eight of just pure grill”: A multischool qualitative study of student abuse. Acad Med. 2011;86:1374–1382. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182303c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook DJ, Liutkus JF, Risdon CL, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH, Walter SD. Residents’ experiences of abuse, discrimination and sexual harassment during residency training. CMAJ. 1996;154:1657–1665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krueger RA. Developing Questions for Focus Groups. Vol 3. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krueger RA. Moderating Focus Groups. Vol 4. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger RA. Analyzing & Reporting Focus Group Results. Vol 6. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherbino J, Frank JR, Flynn L, Snell L. “Intrinsic roles” rather than “armour”: Renaming the “non-medical expert roles” of the CanMEDS framework to match their intent. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16:695–697. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9318-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: Longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006;333:682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV, White K, Leibowitz A, Baldwin DC., Jr A pilot study of medical student ‘abuse’. Student perceptions of mistreatment and misconduct in medical school. JAMA. 1990;263:533–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silver HK, Glicken AD. Medical student abuse. Incidence, severity, and significance. JAMA. 1990;263:527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf TM, Randall HM, von Almen K, Tynes LL. Perceived mistreatment and attitude change by graduating medical students: A retrospective study. Med Educ. 1991;25:182–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seabrook M. Intimidation in medical education: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Stud Higher Educ. 2004;29:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musselman LJ, MacRae HM, Reznick RK, Lingard LA. “You learn better under the gun”: Intimidation and harassment in surgical education. Med Educ. 2005;39:926–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moscarello R, Margittai KJ, Rossi M. Differences in abuse reported by female and male Canadian medical students. CMAJ. 1994;150:357–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maslow A. Motivation and Personality. New York, NY: Harper; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson J. Student voice motivating students through empowerment. OSSC Bull. 1991;35(2) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seigel S, Rockwood V. Democratic education, student empowerment, and community service: Theory and practice. Equity Excell Educ. 1993;26(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shor I. Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: Causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1613–1622. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elnicki DM, Linger B, Asch E, et al. Patterns of medical student abuse during the internal medicine clerkship: Perspectives of students at 11 medical schools. Acad Med. 1999;74(10 suppl):S99–S101. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]