Abstract

Cancer is one of the most threatening diseases in the world and great interests have been paid to discover accurate and noninvasive methods for cancer diagnosis. The value of microRNA-200 (miRNA-200, miR-200) family has been revealed in many studies. However, the results from various studies were inconsistent, and thus a meta-analysis was designed and performed to assess the overall value of miRNA200 in cancer diagnosis. Relevant studies were searched electronically from the following databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure. Keyword combined with “miR-200,” “cancer,” and “diagnosis” in any fields was used for searching relevant studies. Then, the pooled sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC), and partial AUC were calculated using the random-effects model. Heterogeneity among individual studies was also explored by subgroup analyses. A total of 28 studies from 18 articles with an overall sample size of 3676 subjects (2097 patients and 1579 controls) were included in this meta-analysis. The overall sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are 0.709 (95% CI: 0.657–0.755) and 0.667 (95% CI: 0.617–0.713), respectively. Additionally, AUC and partial AUC for the pooled data is 0.735 and 0.627, respectively. Subgroup analyses revealed that using miRNA-200 family for cancer diagnosis is more effective in white than in Asian ethnic groups. In addition, cancer diagnosis by miRNA using circulating specimen is more effective than that using noncirculating specimen. Finally, miRNA is more accurate in diagnosing endometrial cancer than other types of cancer, and some miRNA family members (miR-200b and miR-429) have superior diagnostic accuracy than other miR-200 family members. In conclusion, the profiling of miRNA-200 family is likely to be a valuable tool in cancer detection and diagnosis.

Keywords: MicroRNA-200 family, diagnosis, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Cancer Report 2014, it was estimated that 14 million people have been diagnosed with cancer and 8.2 million people died from cancer in 2012.1 It is predicted that around 25 million people would be trapped by cancer in 2032.1 Several organizations and institutions have indicated that cancer distribution and mortality varied by different countries and the increasing number of death due to cancer has become a global challenge. Thus, reducing cancer incidence and mortality has a substantial impact on the world. Numerous studies and clinical trials have focused on discovering the early detection and diagnosis methods which are the keys to the survival of patients with cancer.2

Current cancer diagnosis standard is based on pathological evidence, and it usually involves invasive procedures.3 Although imaging screening test (such as computed tomography and low-dose computed tomography) could provide an effective way for detecting microtumors, the issue of over diagnosis and radiation caused by imaging screening tests is still unsolved.4 However, biomarkers, another extensively studied method to assess tumor in the initial stages, have several advantages including noninvasion to human body, low cost, and repeatability.3 However, the application of proposed tumor biomarkers, such as cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA21-1), carcinoembryonic antigen, neuron-specific enolase, tissue polypeptide-specific antigen, chromogranin A, antigenic determinant (CA125), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), was restricted due to their limited sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, it is critical to explore alternative biomarkers for the early detection and diagnosis of cancer.4

Recently, a lot of attention has been focused on MicroRNAs which could be considered as potential biomarkers. MicroRNAs are a class of short noncoding RNA molecules with significant capacity to regulate gene expressions. The miR-200 family, which includes 5 members (miRNA-200a, miRNA-200b, miRNA-200c, miRNA-429, and miRNA-141), is expected to have significant clinical values.5 The suppressive effect of miR-200 on metastases of and metastatic-like primary tumors was discovered by 2 independent groups.6,7 Subsequent studies have verified the dysregulation of the miR-200 family in a variety of cancers, such as ovarian,5 bladder,8 breast,9,10 and prostate.11 Apart from that, miR-200 family is extremely stable in the blood cell and serum. As a result of this, miR-200 family could be considered as a potential candidate for accurate and noninvasive cancer diagnosis.12–14

Numerous researches have been conducted to explore the effectiveness of the miR-200 family in tumor detection. The diagnostic feasibility of those miRNAs has been explored in prostate, lung, ovarian, endometrial, breast, gastric, bladder, renal cell, cervical, and colorectal cancer using various specimens, including the serum, sputum, blood, tissue, plasma, and urine.14–31 The highest sensitivity and specificity level of miR-200 in cancer detection were 97.5% and 100%, whereas the lowest sensitivity and specificity level of miR-200 were 47.3%25 and 32.1%, respectively.19 Therefore, the accuracy of miR-200 for cancer detention varied substantially among individual studies. Some studies indicated inconsistency between sensitivity and specificity, whereas others had less conflicting results.14,17,20–24,26,29,31 Intuitively, the substantial difference in the sensitivity and specificity among different studies could be attributed to a wide range of factors including sample size, ethnicity, population structure, specimen, cancer types, and types of applied miR-200 family. Therefore, a meta-analysis was performed to investigate the overall validity and accuracy of miR-200 in cancer detection and diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

Relevant studies were searched electronically from the following databases, including Chinese Biological Medicine (CBM), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Embase, and PubMed, and articles up to July 28, 2015, were included in the searching criteria. The following searching keywords were used: (“MIRN200 microRNA, human” OR “miR-200” OR “miR-429” OR “miR-141” OR “miR-200a” OR “miR-200b” OR “miR-200c”) AND (“diagnoses” OR “sensitivity” OR “specificity” OR “ROC curve”) AND (“cancer” OR “tumor” OR “neoplasm” OR “malignancy”). The searching keywords were constructed by combining 3 supplementary concepts, naming “cancer,” “MiR-200,” “human,” and “diagnosis” with their synonyms suggested by the database. These keywords have been searched in all fields, and some study references were also screened manually to reduce selection bias.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following 5 criteria were used to determine the eligibility of studies to be included in the meta-analysis: (1) at least one member of miR-200 family has been applied to diagnose cancer; (2) the gold standard is used to confirm the diagnostic results of cancer; (3) studies are conducted on humans; (4) samples consist of a case group and a control group with cancer-free specimens; (5) there are enough data in the study to derive or reconstruct a 2 by 2 table containing true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative values. Researches with any of the exclusion criteria have been ruled out: (1) reviews, case reports, and letters; (2) studies with incomplete data; (3) studies without a gold standard for cancer diagnosis; (4) duplicated studies or articles.

Data extraction and document assessment

Data extraction was carried out by 2 independent investigators who reviewed the full texts of all included articles. Then, sensitivity, specificity, true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative were calculated for each of the included studies. Moreover, other study information (first author, year, and country of publication), characteristics of study population (ethnicity, sample size, and source of control), and corresponding data of meta-analysis (specimen, detection method, and members of miRNA) were recorded. Finally, the quality of selected articles was assessed by the revised quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS-2).32 Each item of the QUADAS-2 quality assessment list was answered with a yes, no, or unclear and the score of each study calculated individually.

Statistical methods

The sensitivity and specificity together with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were summarized by the random-effects model. The diagnostic accuracy was assessed using the overall summary receiver operator characteristic (SROC) curve and the area under the SROC curve (AUC). Apart from that, a χ2 test was implemented to infer the heterogeneity among individual studies. If the P-value of the χ2 test is <0.05, then there is significant heterogeneity among individual studies. Subgroup analyses were conducted to identify factors which contribute to the significant heterogeneity among individual studies. All statistical analyses were implemented using R 3.2.1 software.

RESULTS

Literature search

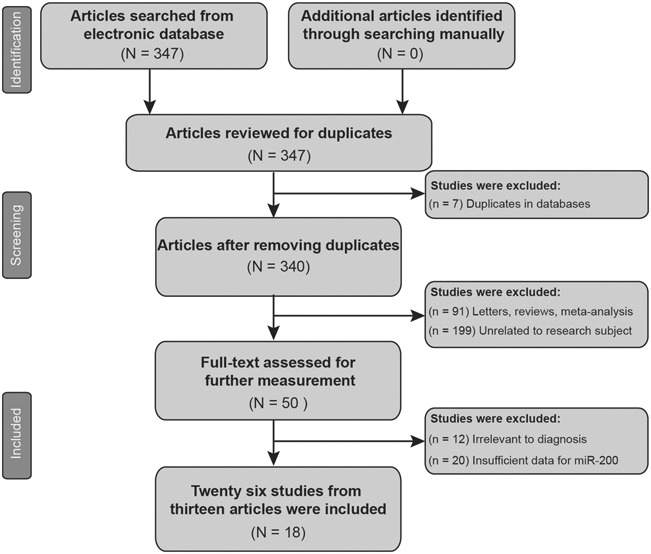

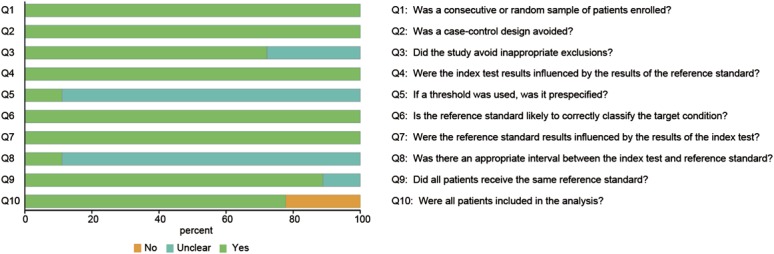

A total of 347 articles were initially selected using the searching strategy, and 7 of the articles were excluded because of duplications. Another 290 of those articles were excluded because of the exclusion criteria mentioned earlier. After that, 32 of the 50 remaining articles were further excluded because of irrelevant research topics or insufficient data. Finally, 18 articles including 28 studies were identified as eligible studies in this meta-analysis.14–31 The literature selection flow chart is illustrated in Figure 1. The result of QUADAS-2 score is shown in Figure 2 and an average QUADAS-2 score of 8 suggests a satisfactory quality of the eligible articles.

FIGURE 1.

Literature selection flow chart.

FIGURE 2.

QUADAS-2 score for quality assessment.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

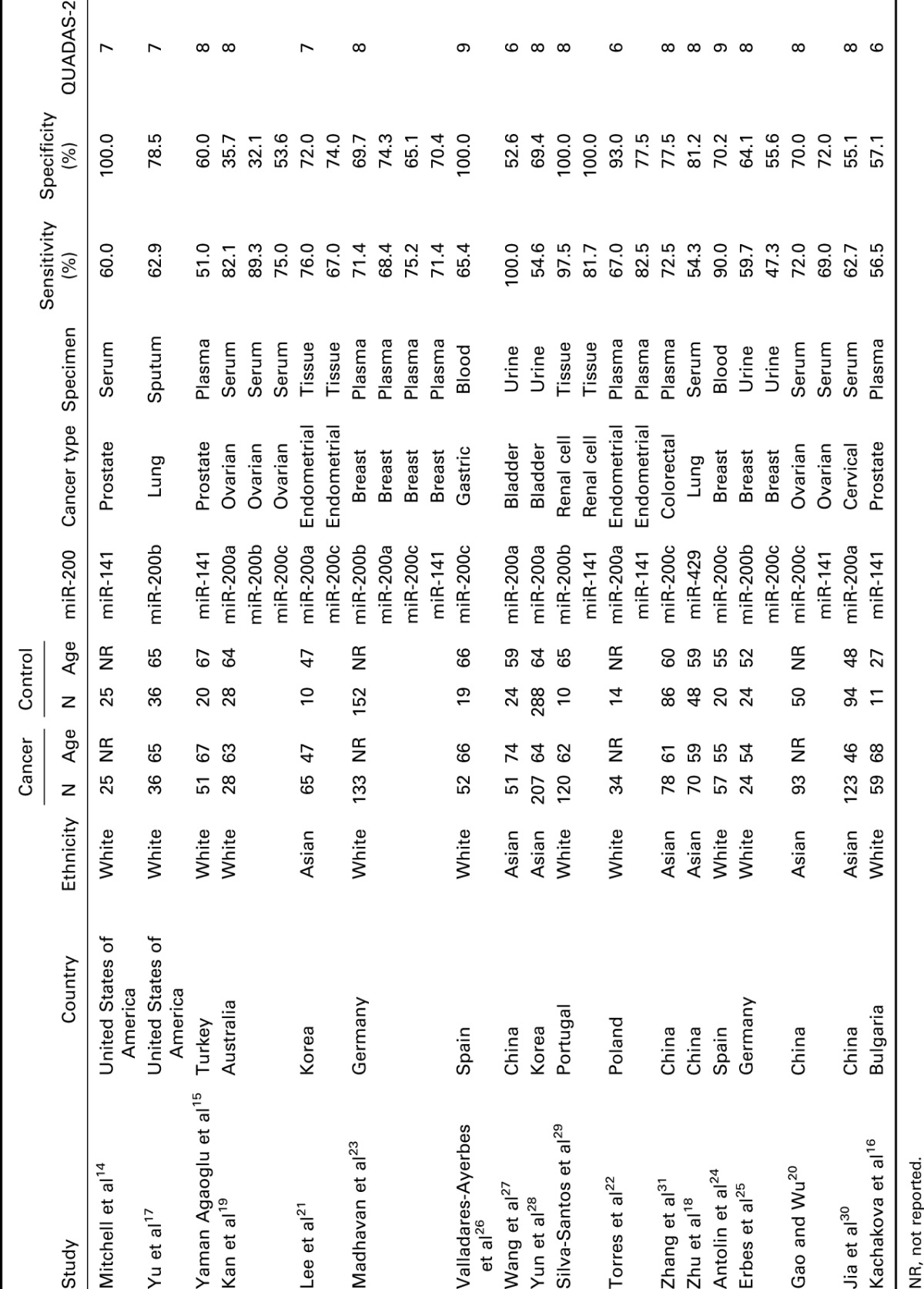

Table 1 indicates the main characteristics of the 18 studies which were included in the meta-analysis with an overall sample size of 3676 (2097 cases, 1579 controls). The 18 studies were stratified by 2 ethnic groups (Asian and white). Moreover, different types of cancer were investigated, including prostate, ovarian, endometrial, breast, gastric, bladder, renal cell, colorectal, cervical, and lung cancer. In addition, 6 types of specimen were applied in these studies including the plasma, serum, tissue, urine, blood, and sputum. All of the 5 members in miR-200 family have been tested (miR-200c: 8 studies, miR-200b: 5 studies, miR-200a: 7 studies, miR-141: 7 studies, and miR-429: 1 study). All of the 28 studies were published between 2008 and 2015.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of 18 studies included in meta-analysis.

Diagnostic accuracy of miR-200 family in cancer

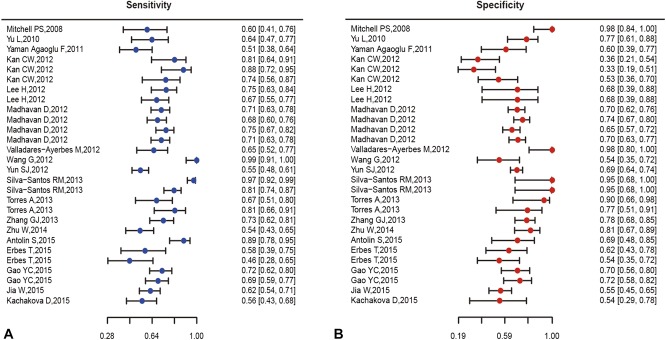

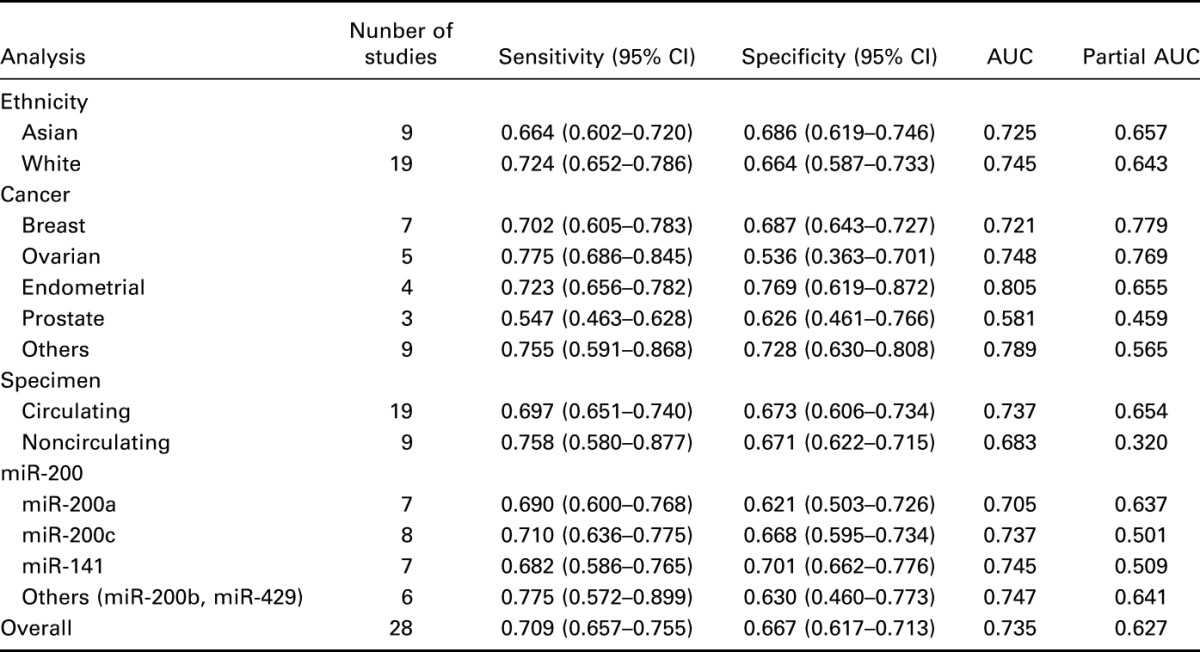

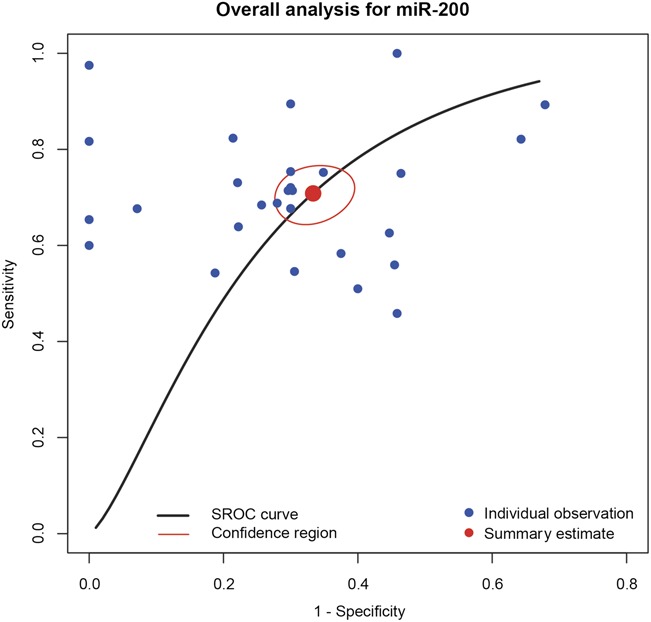

The pooled analysis of miR-200 family in cancer diagnosis is summarized in Table 2, and forest plots on sensitivity and specificity of individual studies are shown in Figure 3. The pooled sensitivity and specificity with their 95% confidence segments are 0.709 (95% CI: 0.657–0.755) and 0.667 (95% CI: 0.617–0.713), respectively. The pooled AUC and partial AUC is 0.735 and 0.627, indicating a moderate accuracy for cancer detection (Figure 4). The P-value of the χ2 test for heterogeneity is <0.01, suggesting a statistically significant interstudy heterogeneity. As a result of this, subgroup analyses should be carried out to investigate the heterogeneity among individual studies.

Table 2.

Summary estimates of diagnostic performance of miR-200 family for cancer detection.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plots of sensitivity (A) and specificity (B) for included studies.

FIGURE 4.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of miR-200.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate how different study characteristics such as subject ethnicity, cancer types, specimen, and miR-200 profiling affect the accuracy of miR-200 for cancer detention.

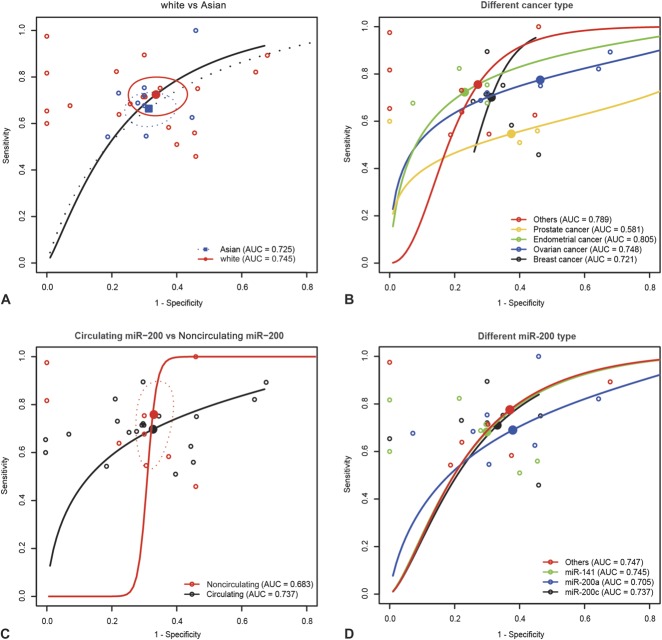

Results from Table 2 suggest that the sensitivity of miR-200 family for cancer detection in the white group was higher than that in the Asian group (0.724 > 0.664, P < 0.05), whereas the specificity in the Asian group was no different than that in the white group (0.686 vs. 0.664, P = 0.141). Additionally, AUC in the white group was 0.745 and 0.725 in the Asian group as suggested by the SROC curve of “white versus Asian” (Figure 5A). However, the partial AUC of the white group was 0.643, which was lower than that of the Asian group of 0.657. Therefore, the difference in the sensitivity and specificity of miR-200 for cancer detection could be attributed to the difference in ethnicity.

FIGURE 5.

Subgroup analysis by ethnicity, cancer types, specimen, miR-200 (A, white vs. Asian; B, different types of cancer; C, circulating miR-200 vs. noncirculating miR-200; D, different types of miR-200).

Subgroup analysis by cancer types (breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, and other cancer) is also revealed in Table 2. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and partial AUC of miR-200 for detecting breast cancer was 0.702 (95% CI: 0.605–0.783), 0.687 (95% CI: 0.643–0.727), 0.721 and 0.779, respectively. Similarly, the above figures of miR-200 for detecting ovarian cancer was 0.775 (95% CI: 0.686–0.845), 0.536 (95% CI: 0.363–0.701), 0.748, and 0.769. Moreover, miR-200 for detecting endometrial cancer had the highest specificity and AUC (0.769, 0.805). Corresponding figures of miR-200 for detecting prostate cancer was 0.547 (95% CI: 0.463–0.628), 0.626 (95% CI: 0.461–0.766), 0.581, and 0.459, respectively. Finally, corresponding figures of miR-200 for detecting other cancers were 0.755 (95% CI: 0.591–0.868), 0.728 (95% CI: 0.630–0.808), 0.789, and 0.565, respectively. The difference in the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC between the 5 cancer types is illustrated in Figure 5B.

The difference in sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and partial AUC was also investigated by different types of specimen. Two types of specimen were considered by the subgroup analysis: circulating group (serum, plasma, blood) and noncirculating group (sputum, tissue, urine). Table 2 suggests that miR-200 with circulating specimen had higher specificity, AUC, and partial AUC, whereas miR-200 with noncirculating specimen had higher sensitivity. The sensitivity and specificity of the circulating and noncirculating subgroups were 0.697 versus 0.758 (P < 0.05) and 0.673 versus 0.671 (P = 0.873). The SROC curves of “circulating miR-200 versus noncirculating miR-200” (Figure 5C) are plotted in Figure 5. The AUC and partial AUC of the circulating subgroup were 0.737 and 0.654, which were higher than that of the noncirculating group (0.683, 0.320).

Subgroup analysis by miR-200 profiling (miR-200a, miR-200c, miR-141, others) suggests that the diagnostic accuracy of miR-200 family varied for different miR-200 members. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and partial AUC of group based on miR-200a are 0.690 (95% CI: 0.600–0.768), 0.621 (95% CI: 0.503–0.726), 0.705, and 0.637. The corresponding figures of miR-200c are 0.710 (95% CI: 0.636–0.775), 0.668 (95% CI: 0.595–0.734), 0.737, and 0.501. The third group (miR-141) has the highest specificity. The corresponding results of the third group are 0.682 (95% CI: 0.586–0.765), 0.701 (95% CI: 0.662–0.776), 0.745, and 0.509. The fourth subgroup (miR-200b and miR-429) have the highest sensitivity, AUC, and partial AUC. Corresponding figures of the fourth group are 0.775 (95% CI: 0.572–0.899), 0.630 (95% CI: 0.460–0.773), 0.747, and 0.641.

DISCUSSION

Cancer has been considered as one of the major threats to human beings because of its high mortality, and a lot of effort has been made to discover effective diagnosis and treatment methods. Recently, enormous studies have contributed to unfold alternative diagnostic methods, as the early detection and diagnosis of cancer is critical to the survival of patients with cancer. Conventional cancer detection methods are often criticized by many drawbacks such as invasion to human body,3 high health risk,4 and misdiagnosis due to low sensitivity and specificity.3 However, miR-200 dysregulation has been found in various cancers,6,7 and miR-200 is extremely stable in the blood system.12–14 Therefore, miR-200 has been considered as the novel biomarker for cancer diagnosis, and evidence has suggested that miR-200 plays a key role in the development of tumors. One recent review summarized that miR-200 has dysregulation in 17 types of cancer.5 In addition, several studies have explored miR-200 family members as indicators for cancer detection.14–31 Thorough research and data extraction enabled us to include 18 articles together with 28 eligible studies in the meta-analysis. However, the diagnostic value of miR-200 for detecting cancer remained unclear because of significant heterogeneity among individual studies.

Results from the meta-analysis suggest that the overall AUC, a useful indicator for diagnostic accuracy, is 0.735. In addition, the pooled sensitivity and specificity with their 95% CIs are 0.709 (95% CI: 0.657–0.755) and 0.667 (95% CI: 0.617–0.713), respectively. As a result of this, the diagnostic accuracy of miR-200 is considered to be neutral.

Subgroup analysis by ethnicity revealed that miR-200 in the white group has higher sensitivity and larger AUC than the Asian group. Significant heterogeneity among individual studies may contribute to this phenomenon, such as unmatched sample size, different miR-200 family members, and different types of cancer. Four miR-200 family members (miR-200a, miR-200c, miR-141, miR-429) were applied in the Aisan group, whereas all subtypes of miR-200 family members were tested in the white group. Diagnostic accuracy using miR-200 in the white group is more reliable than in the Asian group. Therefore, miR-200 is more likely to be an applicable biomarker for cancer detection in whites.

A subgroup analysis by types of cancer was also conducted to assess how different types of cancer affect the diagnostic accuracy of miR-200. Cancer types were divided into 5 groups: breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, and other cancers (include gastric, colorectal, cervical, lung, bladder, and renal cell cancer). Our results suggest that the diagnostic accuracy varied for different types of cancer. For example, miR-200 in endometrial cancer had comparatively high specificity and AUC, whereas miR-200 in ovarian cancer had comparatively high sensitivity. This may be explained by heterogeneity that arises from many factors, including various specimens, unmatched sample sizes, and different ethnicities. Since the diagnostic accuracy of miR-200 was relatively high in endometrial and ovarian cancers, miR-200 family members might be considered as biomarkers for detecting endometrial and ovarian cancers. It is strongly recommended that future studies with matched sample size, ethnicity, and specimen should be designed and performed to confirm the conclusion.

Another subgroup analysis by specimen indicates that miR200 using circulating specimen (serum, plasma, blood) for cancer detection was more accurate than that using noncirculating specimen (sputum, tissue, urine) because of the relatively high specificity, AUC, and partial AUC. However, noncirculating specimen had higher sensitivity than that of circulating specimen. This may arise from unmatched sample size, different ethnicity, and different types of cancer. For example, only 1146 samples from 9 studies were tested using noncirculating specimen, whereas more than half of the study cases were involved in circulating specimen. In addition, ethnicity was not evenly distributed in the 2 groups of specimen. The circulating group contained mainly whites, whereas the noncirculating group contained mainly Asian, and the different ethnicity distribution in the 2 specimen groups might result in difference in the diagnostic accuracy of miR-200. Since circulating specimen group had more accurate diagnostic accuracy than the non-circulating specimen group, miR-200 is more likely to be an applicable biomarker for cancer detention using circulating specimen.

Finally, 28 studies were divided into 4 groups based on the miR-200 family members: miR-200a, miR-200c, miR-141, and others (miR-200b, miR-429). As suggested by Table 2, miR-200b and miR-429 show the highest potency in cancer diagnoses because of the highest sensitivity, AUC, and partial AUC, whereas miR-141 had the highest specificity and lowest sensitivity. The disparity of diagnostic accuracy among different miR-200 family members suggests the great possibility of mi-RNA class being the resource of heterogeneity. Our results revealed that miR-200b and miR-429 were more accurate than other miR-200 family members for cancer diagnosis, except for their relatively low specificity. One possible solution might be using miR-200 as a parallel test together with other diagnostic tests, then the negative result would only be confirmed when both tests are negative. Some researches have adopted similar strategies which are more effective than conventional diagnosis methods.19,33

Nevertheless, certain limitations still exist in the meta-analysis. As discussed in the subgroup analyses, the imparity of ethnicity remained to be clarified, and this might be considered as a source of heterogeneity among individual studies. Moreover, all the eligible studies included in the meta-analysis were based on single mi-RNA profiling, which might be inadequate to evaluate the diagnostic value of the miR-200 family as biomarker for cancer detection. Since not all members of the miR-200 family share the same dysregulation model in human cancers,3,5 the function in cell division and apoptosis is different as well;34–36 it is necessary to carry out further analysis to investigate how multiple miRNA profiling affects the diagnostic accuracy for cancer detention. Finally, publication bias of included studies was not evaluated which could be another concern to the result of the meta-analysis.

In conclusion, miR-200, especially miR-200b and miR-429, may provide a valuable reference for cancer detection. Alternatively, miR-200 family members could be used in conjunction with other cancer diagnosis methods. However, studies matched by confounding factors such as ethnicity and specimen should be designed to confirm the diagnostic value of miR-200.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate their colleagues for their constructive comments on this article.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender E. Developing world: global warning. Nature. 2014;509:S64–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zen K, Zhang CY. Circulating microRNAs: a novel class of biomarkers to diagnose and monitor human cancers. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:326–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mascalchi M, Belli G, Zappa M, et al. Risk-benefit analysis of X-ray exposure associated with lung cancer screening in the Italung-CT trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng X, Wang Z, Fillmore R, et al. MiR-200, a new star miRNA in human cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;344:166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson P, Lu J, Zhang H, et al. MicroRNA dynamics in the stages of tumorigenesis correlate with hallmark capabilities of cancer. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2152–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons DL, Lin W, Creighton CJ, et al. Contextual extracellular cues promote tumor cell EMT and metastasis by regulating miR-200 family expression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2140–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiklund ED, Bramsen JB, Hulf T, et al. Coordinated epigenetic repression of the miR-200 family and miR-205 in invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1327–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Roslan S, Johnstone CN, et al. MiR-200 can repress breast cancer metastasis through ZEB1-independent but moesin-dependent pathways. Oncogene. 2014;33:4077–4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manavalan TT, Teng Y, Litchfield LM, et al. Reduced expression of miR-200 family members contributes to antiestrogen resistance in LY2 human breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barron N, Keenan J, Gammell P, et al. Biochemical relapse following radical prostatectomy and miR-200a levels in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2012;72:1193–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilad S, Meiri E, Yogev Y, et al. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2009;58:1375–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaman Agaoglu F, Kovancilar M, Dizdar Y, et al. Investigation of miR-21, miR-141, and miR-221 in blood circulation of patients with prostate cancer. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kachakova D, Mitkova A, Popov E, et al. Combinations of serum prostate-specific antigen and plasma expression levels of let-7c, miR-30c, miR-141, and miR-375 as potential better diagnostic biomarkers for prostate cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2015;34:189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L, Todd NW, Xing L, et al. Early detection of lung adenocarcinoma in sputum by a panel of microRNA markers. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2870–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu W, He J, Chen D, et al. Expression of miR-29c, miR-93, and miR-429 as potential biomarkers for detection of early stage non-small lung cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kan CW, Hahn MA, Gard GB, et al. Elevated levels of circulating microRNA-200 family members correlate with serous epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao YC, Wu J. MicroRNA-200c and microRNA-141 as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:4843–4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Choi HJ, Kang CS, et al. Expression of miRNAs and PTEN in endometrial specimens ranging from histologically normal to hyperplasia and endometrial adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1508–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres A, Torres K, Pesci A, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of miRNA signatures in tissues and plasma of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1633–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madhavan D, Zucknick M, Wallwiener M, et al. Circulating miRNAs as surrogate markers for circulating tumor cells and prognostic markers in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5972–5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antolin S, Calvo L, Blanco-Calvo M, et al. Circulating miR-200c and miR-141 and outcomes in patients with breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erbes T, Hirschfeld M, Rucker G, et al. Feasibility of urinary microRNA detection in breast cancer patients and its potential as an innovative non-invasive biomarker. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valladares-Ayerbes M, Reboredo M, Medina-Villaamil V, et al. Circulating miR-200c as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer. J Transl Med. 2012;10:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G, Chan ES, Kwan BC, et al. Expression of microRNAs in the urine of patients with bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yun SJ, Jeong P, Kim WT, et al. Cell-free microRNAs in urine as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva-Santos RM, Costa-Pinheiro P, Luis A, et al. MicroRNA profile: a promising ancillary tool for accurate renal cell tumour diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2646–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia W, Wu Y, Zhang Q, et al. Expression profile of circulating microRNAs as a promising fingerprint for cervical cancer diagnosis and monitoring. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:851–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang GJ, Zhou T, Liu ZL, et al. Plasma miR-200c and miR-18a as potential biomarkers for the detection of colorectal carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen J, Liao J, Guarnera MA, et al. Analysis of MicroRNAs in sputum to Improve computed tomography for lung Cancer diagnosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao CX, Wei QX, Zhang YY, et al. miR-200b targets GATA-4 during cell growth and differentiation. RNA Biol. 2013;10:465–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia W, Li J, Chen L, et al. MicroRNA-200b regulates cyclin D1 expression and promotes S-phase entry by targeting RND3 in HeLa cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;344:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schickel R, Park SM, Murmann AE, et al. miR-200c regulates induction of apoptosis through CD95 by targeting FAP-1. Mol Cell. 2010;38:908–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]