Abstract

Purpose

To measure pediatric program directors’ (PDs’) and trainees’ perceptions of and expectations for the balance of service and education in their training programs.

Method

In fall 2011, an electronic survey was sent to PDs and trainees at Boston Children’s Hospital. Respondents described perceptions and expectations for service and education and rated the education and service inherent to 12 vignettes. Wilcoxon rank sum tests measured the agreement between PD and trainee perceptions and ratings of service and education assigned to each vignette.

Results

Responses were received from 28/39 PDs (78%) and 223/430 trainees (52%). Seventy-five (34%) trainees responded that their education had been compromised by excessive service obligations; only 1 (4%) PD agreed (P < .0001). Although 132 (59%) trainees reported that service obligations usually/sometimes predominated over clinical education, only 3 (11%) PDs agreed (P < .0001). One hundred trainees (45%) thought rotations never/rarely/sometimes provided a balance between education and clinical demands compared with 2 PDs (7%) (P < .0001). Both groups agreed that service can, without formal teaching, be considered educational. Trainees scored 6 vignettes as having greater educational value (P ≤ .01) and 10 as having lower service content (P ≤ .04) than PDs did.

Conclusions

Trainees and medical educators hold mismatched impressions of their training programs’ balance of service and education. Trainees are more likely to report an overabundance of service. These data may impact the interpretation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education survey results and should be incorporated into dialogue about future curricular design initiatives.

Since the original graduate medical education (GME) infrastructure emerged in the early 20th century, medical educators have debated the appropriate role of service in the training environment.1 Having advanced past medical school, residents continue to learn while becoming an invaluable part of an institution’s workforce.2 This duality of roles has the potential to create ambiguity of expectations and role confusion among trainees, faculty members, and their institutional leadership.

In contemporary GME, program directors (PDs) strive to preserve a focus on both service and the educational value of training.3 Given duty hours restrictions, they must think carefully about how residents’ time is best spent. To what extent is resident learning optimized by service activities? How is service defined? The multiple meanings for the term “service” complicate discussions about its optimal role during training. For example, service has traditionally been considered a timeless virtue of a physician and an essential attribute of the humanistic doctor.4 In this vein, the Arnold P. Gold Foundation defines service as “the sharing of one’s talent, time, and resources with those in need; giving beyond what is required.”5 Alternatively, service may simply refer to the work of a physician, more specifically, to patient care duties.

An annual resident survey conducted by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) brings intensified attention to the questions of how to define service and how to balance service content and educational value for trainees. Since 2003, the resident survey has facilitated data collection regarding myriad training issues such as resident satisfaction and program quality. At least one survey item addresses the balance between educational activities and service obligations. In 2010, the survey asked, “How often do your rotations and other major assignments provide an appropriate balance between clinical education and other demands, such as service obligations?” and “How often has your clinical education been compromised by excessive service obligations?”6 The following year, the survey asked, “In your opinion, how often do your rotations and other major assignments provide an appropriate balance between your residency education and other clinical demands?”6

According to a publication from Holt and colleagues6, poor performance on these items is not uncommon. In 2007–2008, 39.6% of responses fell short of ACGME expectations, and this “noncompliance” was directly correlated with the number of citations received by the Residency Review Committee. The ACGME survey data may yield serious consequences for PDs, yet survey data remain difficult to interpret. How do trainees define service, and does their definition match that held by PDs? Previous work indicates that such definitions may be specialty specific, yet insight into the views of pediatricians is lacking.7 What are the respective expectations of pediatric residents and their PDs for the balance of service and education? Without demonstrating how PDs and trainees define service, and until their expectations for service are shown to be aligned, educators will struggle to design curricula that will reliably meet trainees’ educational needs.8,9

We surveyed all trainees and PDs at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) to measure their respective expectations for and perceptions of the balance of service and education during training. The aims of the study were to elucidate trainees’ and educators’ expectations and perceptions with regard to the balance of service and education within their residency training programs. Moreover, we aimed to use our data to articulate initial definitions for education and service in the pediatric GME setting.

Method

Study population

We conducted a voluntary survey among directors of the 39 ACGME-accredited training programs at BCH. We identified these individuals with help from the Office of GME. Also eligible were the 430 residents and fellows training within those programs.

Survey

The survey included 25 questions, grouped into three sections, and took approximately 15 minutes to complete. Twenty-three questions had multiple-choice or ordinal response formats, whereas two demographic questions required written responses. The first section measured respondents’ expectations for the balance of service and education and their perceptions of this balance in their own programs. The second section included 12 case vignettes meant to exemplify common training experiences in a children’s hospital. The scenarios were written by two of the investigators (J.K. and D.B.), who are, respectively, an associate PD and a PD. Trainees and PDs rated each scenario on two separate, seven-point Likert scales—one to quantify the respondent’s perception of the scenario’s educational value, and another to quantify the respondent’s perception of the service content intrinsic to the scenario. High ratings on these scales indicated that the respondent perceives the case vignette to exemplify high educational value and large service content, whereas low ratings suggest that the respondent perceives the activity to confer minimal educational value and little service content. The survey concluded with a section collecting demographic information. The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review.

We pilot-tested the survey with six individuals we deemed similar to our target sample (three senior medical educators and three trainees). After pilot testing, we revised the survey to enhance item clarity and ease of responding. Pilot participants were ineligible to participate in the revised survey, which was sent to all other study participants.

Survey process

In the fall of 2011, we obtained support from representatives of all BCH training programs by meeting with the GME Committee. Then we sent PDs an e-mail containing an electronic link to the survey instrument; PDs were asked to forward the e-mail and survey link to the trainees in their program. We did not require PDs to confirm that they had forwarded our survey link to their trainees. In total, we sent three e-mail reminders over the four-week study period. Respondents’ identities were not linked to their survey responses, and we invited respondents to enter their names into a separate dataset so that they could be included in a raffle for one of three $200 gift cards.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used SAS 9.2 statistical software (SAS Inc., Cary, North Carolina). We used Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher exact tests to measure differences between PDs’ and trainees’ expectations and perceptions of the balance of education and service in their programs. Wilcoxon rank sum tests also measured the agreement between ratings of service and education that trainees and PDs assigned to each case vignette. We constructed both median values and ranges and set an alpha level of .05 to establish statistical significance.

Results

We received responses from 28 PDs (78%) and 223 trainees (52%). We excluded from the analyses an additional 22 respondents who did not indicate whether they were a PD or a trainee.

Demographic characteristics

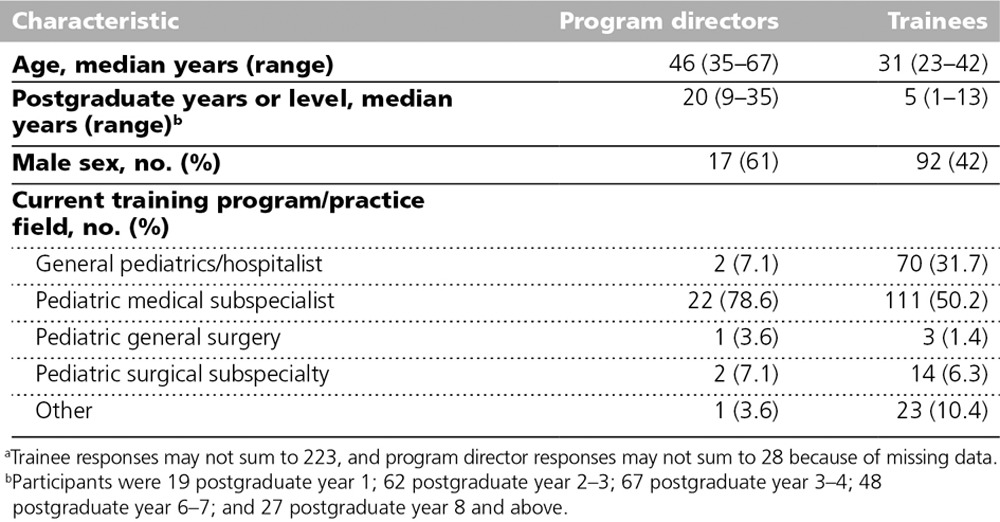

The median age of PDs was 46 years (range 35–67), and 17 (61%) were male (Table 1). Trainees’ median age was 31 years (range 23–42), and 92 (42%) were male. PDs’ median number of postgraduate years was 20 (range 9–35). Median postgraduate level for the trainees was 5 (range 1–13).

Table 1.

Demographic Data for 28 Program Directors and 223 Postgraduate Trainees, From a Study of Perceptions of and Expectations for Service and Education, Boston Children’s Hospital, 2011a

Expectation and perceptions of the balance of education and service

PDs’ and trainees’ responses demonstrated agreement for items pertaining to expectations for the balance of education and service. For example, both PDs (27; 96%) and trainees (200; 90%) endorsed the statement that service can, in the absence of formal teaching, be considered educational. Additionally, when we asked whether it is ever acceptable for a trainee’s duties to include pure service activities, without any explicitly stated educational aims, the groups again responded concordantly. A modest proportion of both PDs (11; 41%) and trainees (104; 47%; P = .68) responded in the affirmative.

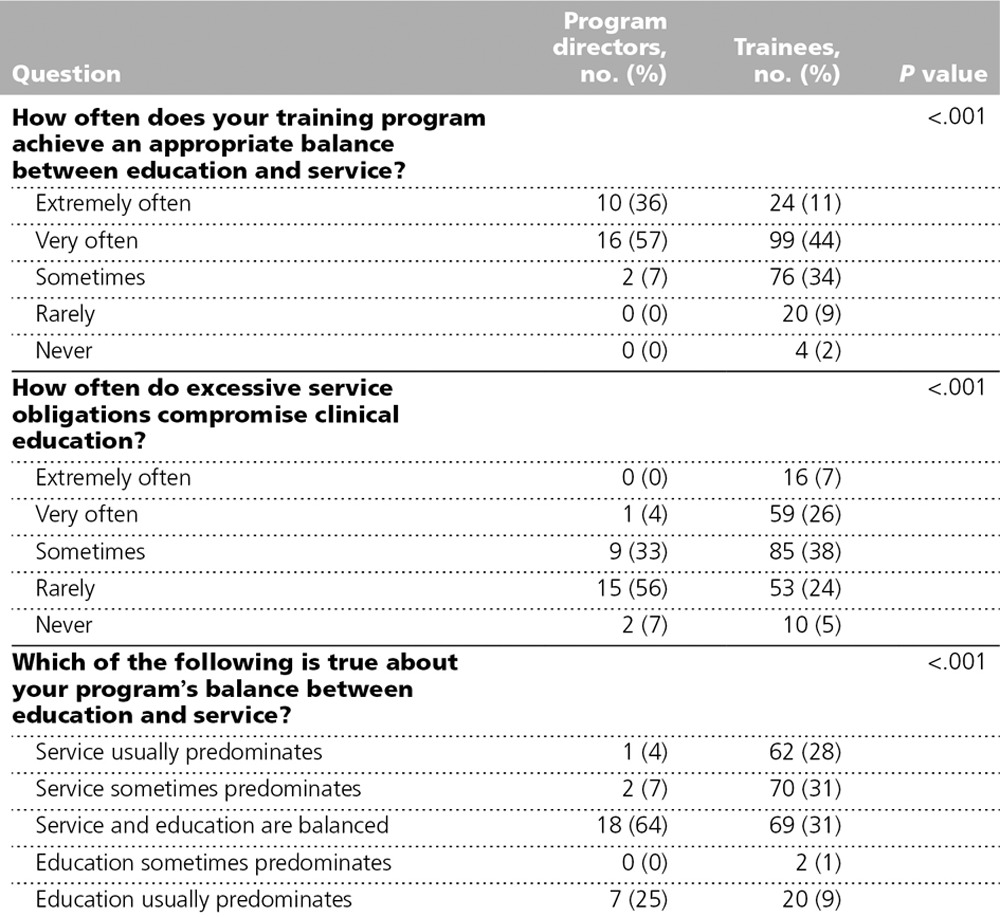

PDs and trainees diverged significantly in their perceptions of the balance of service and education in their own training programs (Table 2). Whereas 100 trainees (45%) report that their program “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” achieves an appropriate balance between education and service, only 2 PDs (7%) agreed (P < .001). When asked how often excessive service commitments compromise clinical education, 75 trainees (34%) answered “extremely” or “very often,” whereas only 1 PD (4%) agreed (P < .001). When asked to consider their training programs as a whole, 132 trainees (59%) report that service “sometimes” or “usually” predominates as compared with only 3 PDs (11%; P < .001).

Table 2.

Twenty-Eight Program Directors’ and 223 Trainees’ Perceptions of the Balance Between Educational Value and Service Content in their Programs, Boston Children’s Hospital, 2011

Effects of postgraduate year status on perceptions

Among our cohort of trainees, we examined whether postgraduate year (PGY) was associated with key survey responses. Respondents reporting experiencing an appropriate balance of education and service “extremely” or “very” often had a higher postgraduate level than respondents answering “rarely” or “never” (year 5 versus year 3, P < .001). Similarly, respondents reporting that excessive service obligations compromise clinical education “extremely” or “very” often had a lower PGY level than respondents answering “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” (year 3 versus year 5, P < .001). Other associations between PGY level and survey responses were not found to be statistically significant.

Ratings of training scenarios

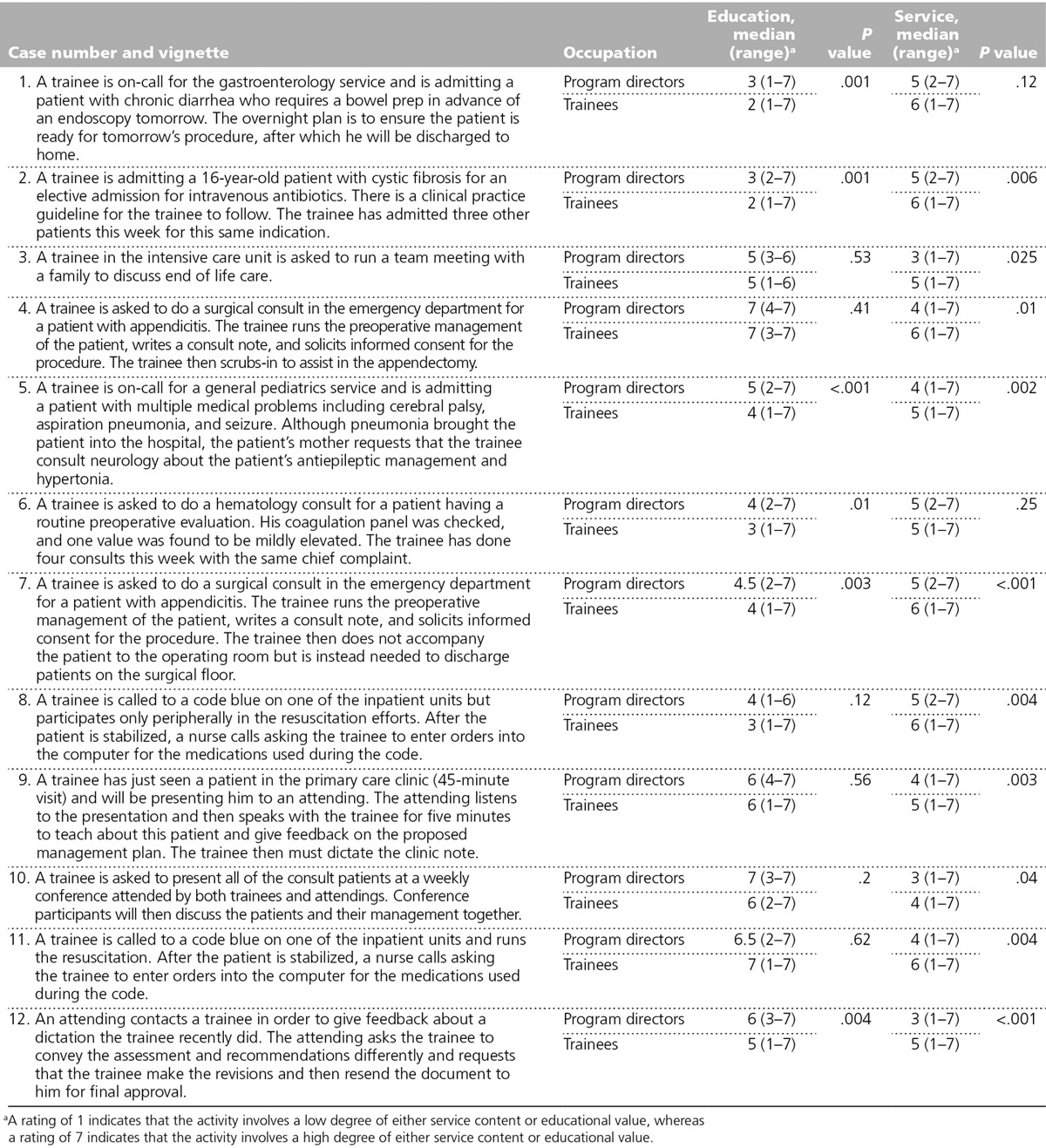

Table 3 displays the ratings that PDs and trainees assigned to each of the 12 vignettes. When examining each vignette, median ratings of the service content represented by each vignette were significantly higher for trainees than PDs in 10 of 12 cases, indicating that trainees were more likely than PDs to perceive a large service content in these 10 training activities. Median ratings of educational value were significantly lower for trainees than PDs in 6 of the 12 cases, demonstrating that trainees perceived lower educational value within these 6 training activities than did the PDs. Higher ratings of educational value for cases 1, 5, and 12 were statistically significantly associated with higher trainee postgraduate level. Higher ratings of service content for cases 4 and 5 were statistically significantly associated with lower trainee postgraduate level.

Table 3.

Comparison of 28 Program Directors’ and 223 Trainees’ Ratings of Education and Service Inherent in Case Vignettes, From a Study of Perceptions of and Expectations for Service and Education, Boston Children’s Hospital, 2011

Definitions of service and education

Examination of the vignettes for which our cohorts gave concordant ratings may provide insight into how our participants define service and education. We found five vignettes for which both cohorts assigned high ratings for service content (median of 5 or higher). Trainees and PDs perceived service content to be high under two circumstances: when the duties become repetitive (as in cases 2 and 6 where the trainee is confronting clinical situations that have been encountered numerous times before) and when the duties pull the trainee away from direct patient care (as in cases 1, 7, and 8 where the trainee is coordinating care in which he or she is only peripherally involved). We also identified six vignettes for which both cohorts assigned high ratings for educational value (median of 5 or higher). Trainees and PDs perceived educational value to be high under two circumstances: when the duties involve direct interactions with patients or family members (as in cases 3, 4, and 11 where the trainee assumes clinical ownership and significant responsibility for patient care) and when the trainee receives individual, patient-oriented teaching from a supervising attending (as in cases 9, 10, and 12 where the trainee receives feedback on clinical management and documentation from one or several attending physicians).

Discussion

Our findings about PDs’ and trainees’ expectations and perceptions of education and service suggest several important conclusions. First, trainees and PDs had similar expectations for training with regard to service and education. For example, 96% of PDs and 90% of trainees reported that service can be considered educational even when formal teaching is absent.

Second, our two cohorts diverged with regard to their perceptions of their own programs. Trainees and PDs had significantly different impressions about the balance of service and education in their programs, with the trainee group consistently perceiving an excess of service content and the consequent potential for educational value to be compromised.

If expectations for education and service were aligned, why were the perceptions of trainees and PDs mismatched? One reason may be that the two groups held discordant definitions of service and education. Indeed, the findings summarized in Table 2 support this hypothesis. To align trainee and PD definitions of what service and education are, the ACGME should provide in its Common Program Requirements document a more specific definition of “service” than is currently available. In its current state, the document uses “service” in numerous ways, sometimes relating it to resident schedules and other times to describe the nature of resident work.10 The ACGME states that learning objectives must “not be compromised by excessive reliance on residents to fulfill non-physician service obligations.” But words like “excessive” remain open to interpretation and may contribute to the incongruent perceptions measured in our work.

Our study provides a strong foundation for the creation of clearer definitions of service and education. Despite giving discordant answers to portions of the survey, both trainees and PDs rated educational value for an activity highest if trainees assume responsibility for direct patient care and have access to attending physicians for individualized teaching and feedback. The two cohorts agreed that service content for an activity is highest when trainees are distant from the bedside, consumed with indirect patient care, and when duties become repetitive. Future work with larger samples is needed to corroborate these findings and more rigorously develop definitions with which PDs and trainees will agree. Establishing consensus-driven definitions may facilitate dialogue between PDs and trainees to better align perceptions of the balance between education and service. These terms, especially once defined, should be used frequently and consistently throughout the training program. Without a uniform vocabulary, trainees and PDs will continue to hold divergent views of their programs’ success in this area. Additionally, because our data demonstrate that both trainees and PDs believe that service activities can indeed provide valuable educational opportunities, medical educators should feel justified in asserting the same in their discussions with residents.

The majority of our training vignettes received higher service ratings and lower education ratings from trainees than from PDs. Despite attempting to create a diverse array of training experiences, trainees’ ratings of service content demonstrated minimal variability, with nearly all scores falling between 5 and 7 on our 7-point Likert scale. This homogeneity reinforces the need to clarify the definition of service and observe the impact that such clarification has on residents’ survey responses. Alternatively, the ACGME could simply ask trainees to rate the educational value of their training experiences, without including questions about service. Such items should be developed with input from trainees to ensure that residents’ perceptions and definitions are well understood as the survey is refined.

Finally, our data suggest that the opinions of trainees regarding this issue may change even over the short duration of their training. Residents from higher PGY levels were more likely to perceive service and education to be well balanced, whereas residents from lower PGY levels were more likely to report an overabundance of service obligations. One could speculate that this difference reflects trainees’ professional growth as they pass through various milestones of competency in their training. Alternatively, duties that are perceived to be service-heavy may become less prevalent in relation to education as PGY level increases. In either case, interventions designed to refine training may need to take into account these differences in attitudes by training year.

Interpretation of our findings requires consideration of our study’s limitations. The data were derived from a single academic children’s hospital and may not be generalizable to other settings. Future work, including a larger, more nationally representative sample of trainees across multiple teaching institutions, would be a valuable next step. Moreover, our sample examined fellows and residents as one large group of trainees, even though their training experiences may be different. In addition, the 12 training scenarios we included in our survey have not been validated for this purpose. Further studies are needed to establish their content and construct validity. Last, portions of our survey relied on respondents’ self-report which, despite the anonymity of the survey, leaves the data vulnerable to social desirability and recall biases.

The service activities of training offer invaluable opportunities for learning, and the training experience would be incomplete without the intentional inclusion of service requirements. Our data demonstrate that although the expectations for the balance of service and education are similar amongst PDs and trainees, their perceptions of the balance of service and education diverge greatly. Further work is needed to clarify definitions of service and education and to explore their optimal balance in GME.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: The study was funded by the Academy for Teaching and Learning at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review.

Previous presentations: These data were previously presented as a poster at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, Boston, Massachusetts; April 30, 2012.

References

- 1.Ludmerer K. Time to Heal: American Medical Education From the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kesselheim AS, Austad KE. Residents: Workers or students in the eyes of the law? N Engl J Med. 2011;364:697–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesselheim JC, Cassel CK. Service: An essential component of graduate medical education. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:500–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1214850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Physicians. ACP Ethics Manual. 6th ed. http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/ethics/manual/manual6th.htm. Accessed December 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold P. Gold Foundation. http://humanism-in-medicine.org/. Accessed December 10, 2013.

- 6.Holt KD, Miller RS, Philibert I, Heard JK, Nasca TJ. Residents’ perspectives on the learning environment: Data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education resident survey. Acad Med. 2010;85:512–518. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccc1db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvin SL, Buys E. Resident perceptions of service versus clinical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:472–478. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00170.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn A, Brunett P. Service versus education: Finding the right balance: A consensus statement from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors 2009 Academic Assembly “Question 19” working group. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(suppl 2):S15–S18. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DE, Johnson B, Jones Y. Service versus education, what are we talking about? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACGME Common Program Requirements. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2013.