Abstract

Background

Black and Latina women in the United States are known to undergo cesarean delivery at a higher rate than other women. We sought to explore the role of medical indications for cesarean delivery as a potential explanation for these differences.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted of 11,034 primiparas delivering at term at the University of California, San Francisco, between 1990 and 2008. We used multivariable analyses to evaluate racial and ethnic differences in risks of, and indications for, cesarean delivery.

Results

The overall rate of cesarean delivery in our cohort was 21.9 percent. Black and Latina women were at significantly higher odds of undergoing cesarean delivery than white women (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.54; 95% CI: 1.30, 1.83, and 1.21; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.43, respectively). Black women were at significantly higher odds of undergoing cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracings than white women (AOR: 2.19; 95% CI: 1.55, 3.09), and black women (AOR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.21, 1.98), Latina women (AOR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.19, 1.85), and Asian women (AOR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.22, 1.85) were at significantly higher odds of undergoing cesarean delivery for failure to progress. Black, Latina, and Asian women were at significantly lower odds of undergoing cesarean delivery for malpresentation than white women (AORs: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.34, 0.89, 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44, 0.98, and 0.55, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.76, respectively).

Conclusions

Racial and ethnic differences exist in specific indications for cesarean delivery among primiparas. Clarifying the possible reasons for increased cesareans for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing in black women, in particular, may help to decrease excess cesarean deliveries in this racial and ethnic group. (BIRTH 39:2 June 2012)

Keywords: race and ethnicity, disparity, cesarean delivery

The rate of cesarean delivery in the United States has increased from 4.5 percent in 1965 (1) to 31.8 percent in 2007 (2). Although much of this rise occurred in the 1970s and 1980s, the cesarean delivery rate has continued to rise by 1 percent per year over the past decade (3). Clinical conditions such as obesity, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and other chronic diseases have been shown to contribute to higher rates of cesarean deliveries, (4–10), in addition to nonclinical factors including patient and provider preferences, insurance type, socioeconomic status, regional differences, legal climate, and increasing maternal age (9–15).

Numerous studies have focused on racial and ethnic differences in cesarean delivery rates, demonstrating that black women have the highest rates nationwide (16–19), even after adjustment for level of education, income, insurance status, and regional practice differences (1, 17, 20, 21). Many hypotheses have been suggested to explain the higher cesarean rates in black women including provider-level practices, hospital-level practices, patient-provider communication, patient preferences, and racial or ethnic discrimination (20–24). However, few studies have examined specific medical indications as a means to explain the differential rates in cesarean delivery across race (16).

Although the documented medical indication for cesarean delivery is the most readily available source of information about the reason for this surgery, its assignment can be somewhat subjective and dependent on the perspective of the medical provider. Comparison of the indications for cesarean delivery may help to clarify potential patient-level differences and specific provider-level practices that may underlie racial and ethnic differences in cesarean delivery rates Our study attempts to examine differences in indications for cesarean section as a means of further elucidating the relationship between race and ethnicity and primary cesarean delivery risk among primiparous women.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of deliveries between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2008, at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. The University of California in San Francisco maintains a clinical perinatal database of all deliveries at that institution. Data on demographic information, insurance information, race/ethnicity, labor course, indications for cesarean delivery, and obstetrical outcomes are all collected at the time of delivery. Indications for cesarean delivery are recorded by an obstetrical provider (generally a resident physician under the supervision of an attending physician) after the procedure. Primiparous women with term (> 37 wk), singleton pregnancies who self-reported their race/ethnicity as black, Latina, Asian, or white were eligible for study inclusion. These categories were considered to be mutually exclusive: Latina or Hispanic ethnicity categorization superseded racial classification. We excluded women transported to the University of California, San Francisco, for delivery from other institutions because ascertainment of antenatal risk factors for cesarean delivery in this population is not as complete as it is for patients receiving prenatal care at University of California, San Francisco Medical Center.

For the purposes of our analyses we grouped participants into one of six cesarean delivery indication categories: 1) “failure to progress,” which included women who were diagnosed with failure to progress in labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, or failed induction of labor; 2) “nonreassuring fetal heart tracing,” consisting of women who were diagnosed with fetal intolerance of labor or fetal distress; 3) “malpresentation,” which included breech and other malpresentations; 4) “previa/bleeding,” which included women with placenta previa or active bleeding requiring cesarean delivery; 5) “failed operative vaginal delivery”; or 6) “other,” which included all other original coded indications for cesarean delivery.

Data Analyses

The primary outcomes for this study were overall risk of cesarean delivery and risk of cesarean delivery for each of the six indications listed above. The primary predictor was maternal race/ethnicity. We first calculated unadjusted odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals for the overall risk of cesarean delivery by race/ethnicity and other demographic and clinical predictors. Using multivariable logistic regression, we then calculated adjusted odds ratios for the risk of cesarean delivery among all women, adjusted for potential confounding variables. We next repeated this process of bivariate and multivariable analyses for each of the six cesarean delivery indications, both for all women as well as among the subgroup of women who had undergone labor. In each case, variables found to be significant (p < 0.05) predictors of cesarean delivery in the bivariate analyses and were retained in the multivariable models.

Although most records included maternal prepregnancy weight, body mass index was missing for a significant proportion of women in the sample. We therefore used multiple imputation methods to impute the missing height values and generated body mass indices for all women whose records included prepregnancy weight. Records that were missing both height and weight values were dropped from further analyses. Variables in the multiple imputation models for height included maternal race/ethnicity as well as prepregnancy weight and weight at delivery, with both weight values log-transformed to better meet linearity assumptions. In each of 10 imputed data sets, missing values of prepregnancy body mass index were calculated from the imputed height values. After the final model for cesarean delivery and each cesarean delivery indication were fitted to the 10 imputed data sets, we used standard methods to compute summary parameter estimates as well as standard errors, confidence intervals, and p values accounting for the loss of information due to missing data (25). These procedures were implemented using the ICE and MICOMBINE commands in STATA (26), the statistical package used for all analyses.

To assess the extent to which there were racial and ethnic differences in neonatal outcomes, we analyzed neonatal Apgar scores and umbilical cord blood gases by race/ethnicity within subgroups of women who underwent cesarean delivery for the indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California San Francisco granted institutional review board approval.

Results

Data from 11,034 primiparous women meeting inclusion criteria between 1990 and 2008 were available for analysis. The racial/ethnic distribution and demographic characteristics by racial/ethnic category of our population are shown in Table 1. In our population the overall cesarean delivery rate was, 21.9 percent. In unadjusted analyses, women of black, Latina, and Asian race/ethnicity were less likely to undergo cesarean delivery when compared with white women (Table 2). Maternal age, increasing body mass index, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, preexisting diabetes, gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, induction of labor, and extremes of infant birthweight were also associated with increased risk of a cesarean delivery in the bivariate analyses, whereas being publicly insured was associated with a decreased risk of cesarean delivery. With the exception of insurance status, all other variables remained significant predictors of cesarean delivery in adjusted analyses.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, stratified by race and ethnicity

| Characteristic | Total (n = 11,034) (%) |

White (n = 6,066) (55.0%) |

Black (n = 1,469) (13.3%) |

Latina (n = 1,328) (12.0%) |

Asian (n = 2,171) (19.7%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, yr (mean + SD) | 28.7 + 6.5 | 30.9 + 5.4 | 22.4 + 6.2 | 25.3 + 6.8 | 28.9 + 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (mean kg/m2 + SD) | 22.8 + 4.6 | 22.6 + 4.0 | 25.4 + 6.4 | 24.0 + 5.0 | 21.1 + 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Public insurance | 1,974 (17.9) | 611 (10.1) | 641 (43.6) | 403 (30.4) | 319 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 539 (4.9) | 309 (5.1) | 138 (9.4) | 25 (2.6) | 57 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic hypertension | 212 (1.9) | 112 (1.9) | 41 (2.8) | 26 (2.0) | 33 (1.5) | 0.048 |

| Preeclampsia | 546 (5.0) | 259 (4.3) | 122 (8.3) | 75 (5.7) | 90 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Pregestational diabetes | 66 (0.6) | 36 (0.6) | 10 (0.7) | 12 (0.9) | 11 (0.5) | 0.003 |

| Gestational diabetes | 444 (4.0) | 166 (2.7) | 39 (2.7) | 73 (5.5) | 166 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 1,548 (14.0) | 715 (11.8) | 191 (13.0) | 228 (17.2) | 414 (19.1) | <0.001 |

| Labor Spontaneous |

8,650 (78.4) |

4,662 (76.9) |

1,142 (77.7) |

1,050 (79.1) |

1,796 (82.7) |

<0.001 |

| Induced | 1,850 (16.8) | 1,050 (17.3) | 282 (19.2) | 227 (17.1) | 291 (13.4) | |

| None | 534 (4.8) | 354 (5.8) | 45 (3.1) | 51 (3.8) | ||

| Infant birthweight <2,500 g |

300 (2.7) |

139 (2.3) |

73 (5.0) |

30 (2.3) |

58 (2.7) |

<0.001 |

| 2,500–4,000g | 9,635 (87.3) | 5,179 (85.4) | 1,304 (88.8) | 1,172 (88.3) | 1,980 (91.2) | |

| >4,000 g | 1,099 (10.0) | 748 (12.3) | 92 (6.3) | 126 (9.5) | 133 (6.1) |

Table 2.

Predictors of cesarean delivery (CD)

| Characteristic | Risk of CD (%) |

Unadjusted OR for CD (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR* for CD (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity White Black Latina Asian |

22.8 20.8 20.8 20.8 |

1.00 (reference) 0.89 (0.77, 1.02) 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) 0.89 (0.79, 1.00) |

1.00 (reference) 1.54 (1.30, 1.83) 1.21 (1.03, 1.43) 1.09 (0.95, 1.24) |

| Maternal age (year) | -- | 1.07 (1.06, 1.07) | 1.08 (1.07, 1.09) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | -- | 1.07 (1.06, 1.08) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) |

| Public insurance | 18.4 | 0.77 (0.68, 0.87) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.01) |

| Chronic hypertension | 28.7 | 1.45 (1.08, 1.96) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.50) |

| Preeclampsia | 34.1 | 1.91 (1.59, 2.30) | 1.82 (1.48, 2.23) |

| Pregestational diabetes | 57.9 | 5.32 (3.37, 8.41) | 4.43 (1.98, 9.90) |

| Gestational diabetes | 32.4 | 1.76 (1.43, 2.16) | 1.28 (1.03, 1.61) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 35.9 | 2.92 (2.57, 3.31) | 2.65 (1.35, 3.00) |

| Induced labor | 28.0 | 1.48 (1.32, 1.67) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.46) |

Adjusted for other covariates listed, plus year of delivery, infant birthweight. and gestational age.

Bolded estimates reflect p < 0.05.

In multivariable models, we found that overall, black and Latina women had increased odds of undergoing cesarean delivery with adjusted odds ratios of 1.54, 95% CI: 1.30, 1.83 and 1.21, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.43, respectively (Table 2). The difference in direction of the effect for minority women between unadjusted and adjusted analyses was accounted for largely by the adjustment for maternal age: the black and Latina women in this population were significantly younger than the white women, and younger women underwent cesarean delivery less often, on average, than did older women.

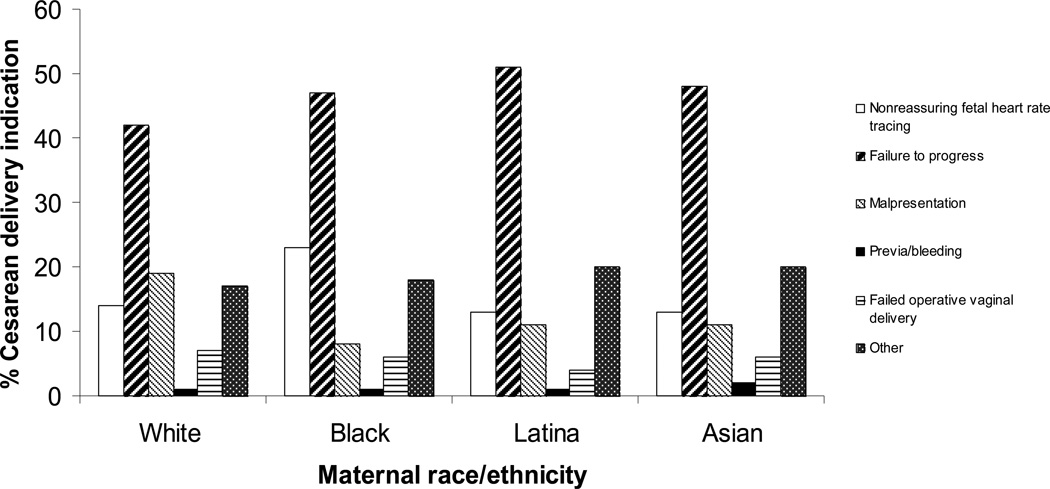

An analysis of the indications for cesarean delivery stratified by race and ethnicity revealed that 23 percent of cesarean deliveries among black women were for the indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing, compared with a rate of 13 to 14 percent for white, Asian, and Latina women (p < 0.001; Fig. 1). In adjusted analyses, black women were more than twice as likely to undergo cesarean delivery for the indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing (AOR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.55, 3.09) when compared with white women. In addition, black (AOR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.22, 1.98), Latina (AOR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.19, 1.85), and Asian (AOR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.77) women were all at increased odds of undergoing cesarean delivery because of failure to progress compared with white women. Black (AOR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.89), Latina (AOR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44, 0.98), and Asian women (AOR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.76) women were all less likely to undergo cesarean delivery for malpresentation than were white women (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Proportion of women with cesarean delivery with each indication for cesarean, by race/ethnicity (p < 0.001 for comparisons across race/ethnic groups).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a of cesarean delivery (CD) for specific indication for each racial/ethnic category

| Indication for CD | Blackb Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

Latinab Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

Asianb Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonreassuring fetal heart tracing | 2.19 (1.55, 3.09) | 1.08 (0.74, 1.59) | 1.01 (0.74, 1.38) |

| Failed progress in labor | 1.55 (1.21, 1.98) | 1.48 (1.19, 1.85) | 1.47 (1.22, 1.85) |

| Malpresentation | 0.54 (0.34, 0.89) | 0.66 (0.44, 0.98) | 0.55 (0.40, 0.76) |

| Previa/bleeding | 1.95 (0.27, 13.6) | 1.24 (0.12, 12.5) | 2.74 (0.62, 12.1) |

| Failed operative vaginal delivery | 0.68 (0.33, 1.39) | 0.59 (0.30, 1.17) | 0.83 (0.53, 1.31) |

| Other indication | 1.56 (1.08, 2.25) | 1.28 (0.90, 1.83) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.42) |

Full models adjusted for race/ethnicity, maternal age, insurance status, year of delivery, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, pregestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, induction of labor, infant birthweight, and gestational age.

Uses white women as the reference group.

Bolded estimates reflect p < 0.05

A subgroup analysis of cesarean indication rates among the 10,500 primiparous women who labored showed similar trends for most indications. In this subgroup, black, Latina, and Asian women were all found to be at increased overall risk of cesarean delivery (AORs: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.41, 2.05, 1.31, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.57 and 1.28, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.48, respectively), as well as for the indication of failure to progress, compared with white women (AOR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.19, 1.95); 1.50, 95% CI: 1.19, 1.88; 1.46, 95% CI: 1.21, 1.76, respectively). Again, black women who labored were more than twice as likely to undergo cesarean delivery for the indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing (AOR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.57, 3.18). Among women who underwent cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing, no racial or ethnic group had significantly different 5-minute Apgar scores, umbilical artery pH, or base excess compared with white women (data not shown), although we may have been underpowered to detect small differences in these measures.

Discussion

The high rate of cesarean delivery is a problem that affects women of different races and ethnicities in the United States to varying degrees. We have demonstrated that after adjustment for chronic diseases, complications of pregnancy, infant birthweight, gestational age, and other sociodemographic factors, black women are more likely to undergo a cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracings than are white women. In addition, black, Latina, and Asian women were all found to be at increased risk compared with white women of undergoing cesarean delivery for failed progress in labor.

Our findings of a higher risk of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing among black women is consistent with those of another group in southern California (16); however, our study benefits from additional model adjustment for potential confounding variables not available to those authors, such as body mass index and medical and obstetrical conditions. Nonreassuring fetal heart tracing is a relatively subjective diagnosis made by the practitioner who is caring for the patient, is based largely on his or her interpretation of the fetal heart rate tracing during labor, and may not be predictive of true fetal compromise necessitating urgent delivery. More objective findings include umbilical cord gas values. If one racial and ethnic group were systematically and inappropriately offered cesarean delivery less often for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing, we would expect to find more neonatal depression and birth asphyxia, with correspondingly lower Apgar scores or more evidence of acidemia in that group, although the low predictive value of fetal heart rate monitoring might preclude significant objective differences. Conversely, if women in one group were inappropriately subjected to more cesarean deliveries than necessary for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing, we might expect the newborns of that group to have better Apgar scores and umbilical cord pH values. Because we did not find any such differences between racial and ethnic groups, one interpretation might be that cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing in these cases was appropriate, reflecting a differential need for a cesarean in some subgroups, and could provide evidence of a true biological difference in the ability of the fetus to tolerate labor. We may also simply have had insufficient power to detect small differences in these outcomes. Notwithstanding, there is difficulty in standardizing interpretations of fetal heart rate tracings and there is known poor interobserver correlation among fetal heart rate tracing interpretations (27). Therefore, validating this finding by comparing the actual fetal heart rate tracings would be exceptionally difficult.

The finding that black women undergo more cesareans for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing could be the result of provider bias. Obstetricians’ estimations of certain racial/ethnic groups and their risk factors may lower their threshold for diagnosing a nonreassuring fetal heart tracing and recommending a cesarean delivery. Similarly, practitioners may perceive a higher degree of medical-legal risk in caring for women from certain backgrounds; medical-legal concerns unquestionably underlie some of the decision-making with respect to delivery mode (28, 29). Yet another possibility is that the differences observed may reflect racial and ethnic variations in women’a willingness to undergo cesarean delivery at the recommendation of the physician. For example, those from some racial and ethnic backgrounds may be more inclined or empowered than others to request management strategies other than cesarean delivery. Each of these hypotheses could be tested using survey methodology, focus groups, or in-depth interviews with patients and providers with respect to their willingness to undergo or to recommend cesarean delivery, respectively.

In the subgroup of women who labored, black, Latina, and Asian patients were all more likely to undergo cesarean delivery for failed progress in labor. Given the broad variation in pelvic anatomy among and between black, Latina, and Asian women, it is unlikely that that all three ethnic groups had anatomy relatively unfavorable for vaginal delivery, suggesting that this indication may also reflect subtle practitioner biases or differences in women’s willingness to undergo cesarean delivery instead of a true biological difference. We also noted that black, Latina, and Asian women were less likely to undergo cesarean delivery for malpresentation. This finding is in agreement with other authors, who have described both lower rates of malpresentation and lower rates of cesarean delivery for malpresented fetuses among racial and ethnic minorities (30–32).

Our study has some limitations. Because of the retrospective nature of this cohort study, our data are vulnerable to possible miscoding and may be best used in the generation of hypotheses for further in-depth study. The data span two recent decades of practice and providers, which represents both a strength and a potential limitation of the study. However, we examined variation in cesarean indications by decade and we did not note any significant differences with the exception of the fact that since 2000, the difference in risk of cesarean delivery for malpresentation for black, Latin, and Asian women when compared with white women has been less pronounced. In addition, birth practices, patient profiles, and patient and provider preferences at our hospital and in our geographical region may be different from those in other settings, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Importantly, our study does not allow us to understand specific practitioner attitudes toward recommending cesarean delivery or women’s preferences with respect to acceptance of cesarean delivery, nor were we able to capture all potential variables that might confound the relationship between race/ethnicity and delivery mode, such as patient educational attainment, use of labor analgesia, and level of support during labor. Finally, the collection of race and ethnicity data may always be subject to error; our study uses self-reported race and ethnicity, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine (33). Notwithstanding the study limitations, we believe our study has identified some possible reasons for racial and ethnic differences in cesarean delivery and may help influence how practitiners think about their decisions with respect to cesarean indication.

Our study focuses on primiparous women undergoing cesarean delivery. Although the procedure is relatively safe, the untoward consequences of disparities in the primary cesarean delivery rate lie in the amplified effects on future pregnancy outcomes. Because of declining rates of vaginal birth after cesarean, women with one prior cesarean are at increased risk for subsequent cesarean deliveries (34). Women with prior cesarean deliveries also bear an increased risk in subsequent pregnancies for stillbirth (35), abnormal placentation, and hysterectomy (36). Therefore, reducing primary cesarean deliveries can also play a key role in reducing future negative pregnancy outcomes.

Conclusions

The climbing rate of cesarean delivery in the United States and elsewhere is an important public health problem that differentially affects women of differing races and ethnicities. Black and Latina women are more likely than other women to have a cesarean delivery, after adjusting for chronic diseases, complications of pregnancy, and sociodemographic factors. Specifically, among women who undergo cesarean delivery, black women are at increased risk of having a cesarean for a nonreassuring fetal heart tracing. Clarifying possible reasons for increased nonreassuring fetal heart tracing in black women may help decrease excess cesarean deliveries in this minority group. In addition, understanding how race and ethnicity affect the complex decision dynamics around the time of cesarean delivery may help to further clarify why this unsettling disparity exists among black and Latina primiparas.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Miriam Kuppermann for her assistance and contributions to the manuscript.

Funding for this publication was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH/NCRR/OD UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 RR024130), Washington, DC, and from the Amos Medical Faculty Development Award of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant No. RWJF-63524), Princeton, New Jersey, USA, to Dr. Allison Bryant. Dr. Aaron Caughey is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as a Physician Faculty Scholar (Grant No. RWJF-61535), Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Contributor Information

Sierra Washington, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Aaron B. Caughey, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Yvonne W. Cheng, in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, California.

Allison S. Bryant, Vincent Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

References

- 1.Braveman P, Egerter S, Edmonston F, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of cesarean delivery, California. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:625–630. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton BE. Births: Preliminary Data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Report. 2009;57:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menacker F, Hamilton BE. Recent trends in cesarean delivery in the United States. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;35:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58:1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paramsothy P, Lin YS, Kernic MA, et al. Interpregnancy weight gain and cesarean delivery risk in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:817–823. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819b33ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, et al. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:29–38. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Getahun D, Kaminsky LM, Elsasser DA, et al. Changes in prepregnancy body mass index between pregnancies and risk of primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(376):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergholt T, Lim LK, Jorgensen JS, et al. Maternal body mass index in the first trimester and risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous women in spontaneous labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(163):e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos GA, Caughey AB. The interrelationship between ethnicity and obesity on obstetric outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linton A, Peterson MR. Effect of preexisting chronic disease on primary cesarean delivery rates by race for births in U. S. military hospitals, 1999–2002. Birth. 2004;31:165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonanno C, Clausing M, Berkowitz R. VBAC: A Medicolegal Perspective. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford RS. Cesarean section use and source of payment: an analysis of California hospital discharge abstracts. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:313–315. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butcher AH, Fos PJ, Zuniga M, et al. Racial variations in cesarean section rates: an analysis of Medicaid data in Louisiana. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1997;3:41–48. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199703000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parrish KM, Holt VL, Easterling TR, et al. Effect of changes in maternal age, parity, and birth weight distribution on primary cesarean delivery rates. JAMA. 1994;271:443–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linton A, Peterson MR. Effect of managed care enrollment on primary and repeat cesarean rates among U. S. Department of Defense health care beneficiaries in military and civilian hospitals worldwide, 1999–2002. Birth. 2004;31:254–264. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getahun D, Strickland D, Lawrence JM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the trends in primary cesarean delivery based on indications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(422):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDorman MF, Menacker F, Declercq E. Cesarean birth in the United States: epidemiology, trends, and outcomes. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coonrod DV, Drachman D, Hobson P, et al. Nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rates: institutional and individual level predictors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(694):e1–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.026. discussion e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linton A, Peterson MR, Williams TV. Effects of maternal characteristics on cesarean delivery rates among U. S. Department of Defense healthcare beneficiaries, 1996–2002. Birth. 2004;31:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.0268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabir AA, Pridjian G, Steinmann WC, et al. Racial differences in cesareans: an analysis of U. S. 2001 National Inpatient Sample Data. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:710–718. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154154.02581.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott-Wright AO, Flanagan TM, Wrona RM. Predictors of cesarean section delivery among college-educated black and white women, Davidson County, Tennessee, 1990–1994. J Natl Med Assoc. 1999;91:273–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant AS, Washington S, Kuppermann M, et al. Quality and equality in obstetric care: racial and ethnic differences in caesarean section delivery rates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:454–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin DE, Savitz DA, Bowes WA, Jr, et al. Race, age, cesarean delivery in a military population. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:530–533. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linton A, Peterson MR, Williams TV. Clinical case mix adjustment of cesarean delivery rates in U. S. military hospitals, 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:598–606. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000149158.21586.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer J, Graham J. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corporation S, editor. StataCorp. STATA Statistical Software, Version 9.0. College Station, Texas: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chauhan SP, Klauser CK, Woodring TC, et al. Intrapartum nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing and prediction of adverse outcomes: interobserver variability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(623):e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rock SM. Malpractice premiums and primary cesarean section rates in New York and Illinois. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:459–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murthy K, Grobman WA, Lee TA, et al. Association between rising professional liability insurance premiums and primary cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1264–1269. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287294.89148.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rayl J, Gibson PJ, Hickok DE. A population-based case-control study of risk factors for breech presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:28–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gregory KD, Korst LM, Krychman M, et al. Variation in vaginal breech delivery rates by hospital type. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:385–390. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HC, El-Sayed YY, Gould JB. Delivery mode by race for breech presentation in the US. J Perinatol. 2007;27:147–153. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine. Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: Final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56:1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Caesarean section and risk of unexplained stillbirth in subsequent pregnancy. Lancet. 2003;362:1779–1784. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14896-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1226–1232. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]