Abstract

This study aimed to determine the within- and between-session reliability of medial gastrocnemius (MG) architecture (e.g. muscle thickness (MT), fascicle length (FL) and pennation angle (PA)), as derived via ultrasonography followed by manual digitization. A single rater recorded three ultrasound images of the relaxed MG muscle belly for both legs of 16 resistance trained males, who were positioned in a pronated position with their knees fully extended and the ankles in a neutral (e.g. 90°) position. A subset of participants (n = 11) were retested under the same conditions ~48-72 hours after baseline testing. The same rater manually digitized each ultrasound image on three occasions to determine MG MT, FL and PA before pooling the data accordingly to allow for within-image (n = 96), between-image (n = 32) and between-session reliability (n = 22) to be determined. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) demonstrated excellent within-image (ICCs = 0.99-1.00, P < 0.001) and very good between-image (ICCs = 0.83-0.95, P < 0.001) and between-session (ICCs = 0.89-0.95, P < 0.001) reliability for MT, FL and PA. Between-session coefficient of variation was low (≤ 3.6%) for each architectural parameter and smallest detectible difference values of 10.6%, 11.4% and 9.8% were attained for MT, FL and PA, respectively. Manually digitizing ultrasound images of the MG muscle at rest yields highly reliable measurements of its architectural properties. Furthermore, changes in MG MT, FL and PA of ≥ 10.6%, 11.4% and 9.8% respectively, as brought about by any form of intervention, should be considered meaningful.

Keywords: Muscle thickness, Fascicle length, Pennation angle, Ultrasound, Smallest detectible difference

INTRODUCTION

Human skeletal muscle architecture (e.g. muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle), influences contractile force and velocity, and thus power output, during dynamic actions [1]. A greater muscle thickness and a larger pennation angle generally increases force capacity whereas a longer fascicle increases maximal shortening velocity [1]. Architectural properties of human skeletal muscle are usually determined by recording sonographic images of the muscle(s) of interest at rest and subsequently digitizing them using image analysis software [2]. Using this approach, recent studies have demonstrated significant correlations between distinct aspects of lateral gastrocnemius (LG) muscle architecture and athletic performance [3, 4]. Medial gastrocnemius (MG) activation was, however, recently reported to be 4.0% and 10.5% greater than soleus and LG activation, respectively, across a range of dynamic and isometric tasks [5]. The aforementioned results suggest that the MG contributes to athletic performance to a greater extent than the other triceps surae muscles and thus MG architectural properties may also demonstrate stronger relationships to performance tasks and elicit greater training adaptations in comparison to soleus and LG. Indeed, it was recently reported that MG muscle thickness and pennation angle were positively correlated to maximal power clean performance [6].

As reported for other variables [7], it is important that derived muscle architecture data is reliable and that the smallest detectable difference (SDD) values are known in order for scientists and practitioners to have confidence in studies reporting either correlations between muscle architectural properties and athletic performance and/or intervention-induced changes in skeletal muscle architecture. Of the triceps surae muscles, reliability of architectural properties attained for the MG has been most extensively reported within the scientific literature [2]. More specifically, the reliability of MG muscle architectural properties taken at rest has been determined for elderly adults (68.1 ± 5.2 years) [8], healthy children (6.6 ± 2.3 years) [9] and children with cerebral palsy [10], but these results may not be transferable to an athletic adult population. Four studies have established measures of reliability of MG muscle architecture at rest in healthy male adults [11–14] which may be more applicable to sports science and medicine research, although as rationalized below, a more comprehensive investigation into the reliability of MG architectural properties is warranted.

For example, two of the above studies reported coefficient of variation (CV) values for MG muscle thickness (2.9-4.8%), fascicle length fascicle length (4.3-5.9%) and pennation angle pennation angle (4.9-9.8%) but these results were established by recording ultrasound images of one participant's MG musculature on either 10 consecutive days [13] or on seven separate occasions within one session [14]. The two more recently published studies did assess multiple (8-10) healthy male adults, but one study assessed within-image reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and typical error (TE)) of fascicle length and pennation angle only [11] and whilst the other study reported between-session ICC and CV values for muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle [12], SDD values were not reported. Furthermore, the two latter studies both extrapolated their fascicle length measurement due the insufficient scanning length (40-50 mm) of the ultrasound probes used [11, 12]. This technique, although widely adopted [2], has been shown to result in a 3.3% underestimation of MG fascicle length (recorded at the mid-belly of the muscle) when compared to direct anatomical inspection [14].

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to determine the within-image, between-image and between-session reliability and SDD values of MG architectural properties (muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle) for athletic males attained from ultrasound images recoded at rest and with MG fascicle length in full view.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

16 resistance trained males (age 23.3 ± 2.8 years, height 1.77 ± 0.09 m and 79.4 ± 10.4 kg) volunteered to participate in this study and provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and conformed to the principles of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki (1983).

Design

This study employed a repeated measures design whereby all participants attended an initial session to have ultrasound images of their MG musculature taken at rest and a subset of participants (n = 11) repeated the process ~48-72 later (at the same time of day).

Methodology

The MG muscle belly was imaged using a 7.5 MHz, 100 mm linear array, B-mode ultrasound probe (MyLab 70 XVision, Esaote, Genoa, Italy) with a depth resolution of 67 mm. Resting images of the MG were captured at the half-way point between medial femoral condyle and the distal muscle-tendon junction while participants lay in a pronated position with the feet neutral (i.e. with the sole of foot at 90° to the tibia) and the knees fully extended [11, 12]. Three images of the MG musculature for both legs were taken by the same experimenter on each testing occasion.

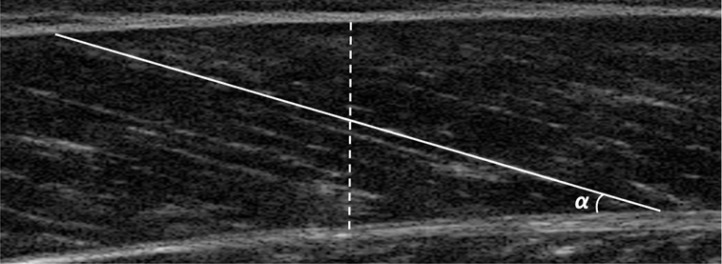

Muscle architectural properties were subsequently analysed using ImageJ software (Wayne Rasband National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Muscle thickness was measured as the vertical distance between the superficial aponeurosis and the deep aponeurosis [12] taken at the centre of the image (Figure 1). Fascicle length was measured directly from the superficial to the deep aponeurosis (Figure 1) and pennation angle was measured as the angle between the deep aponeurosis and the line drawn tangentially to the fascicle [11]. Three measurements of each muscle architectural parameter for the MG of both legs were made by the same experimenter.

FIG. 1.

Example measurement of muscle thickness (dashed line), fascicle length (solid line) and pennation angle (α)

Statistical Analysis

Prior to statistical analysis, data was pooled accordingly to allow for within-image (n = 96), between-image (n = 32) and between-session reliability (n = 22) to be determined. Relative reliability of MG muscle architectural properties was then determined using a two-way random-effects model ICC. The ICC values were interpreted according to previous work [15] where a value of ≥ 0.80 is considered highly reliable. Absolute reliability of the aforementioned parameters was assessed via CV and TE scores. The standard error of measurement (SEM) and SDD were calculated to establish random error scores between testing sessions. The SEM was calculated using equation 1, where SD pooled represents the pooled standard deviation (SD) across the three testing sessions:

| 1 |

The SDD was calculated using equation 2, as in line with previous research [7]:

| 2 |

Repeated measures analysis of variance and a dependent t-test were conducted using SPSS software (version 20; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to assess mean differences among within- and between-session data, respectively. The alpha level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in any architectural parameter noted for within-image, between-image and between session data. Excellent within-image (ICCs = 0.99-1.00, P < 0.001) and very good between-image (ICCs = 0.83-0.95, P < 0.001) and between-session (ICCs = 0.89-0.95, P < 0.001) reliability was found for muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle (Tables 1-2). Between-session CV was low (≤ 3.6%) for each architectural parameter and SDD values of 10.6%, 11.4% and 9.8% were attained for muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle, respectively (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive and reliability statistics for within-session data.

| Variable | Within-Image Data (n = 96) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement 1 Mean ± SD |

Measurement 2 Mean ± SD |

Measurement 2 Mean ± SD |

ICC (90% CI) |

%CV (90% CI) |

TE (90% CI) |

|

| Muscle Thickness (cm) | 2.34 ± 0.31 | 2.34 ± 0.31 | 2.34 ± 0.31 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) |

0.50 (0.42-0.58) |

0.10 (0.09-0.11) |

| Fascicle Length (cm) | 5.49 ± 1.09 | 5.49 ± 1.09 | 5.49 ± 1.10 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) |

1.16 (1.04-1.28) |

0.14 (0.12-0.15) |

| Pennation Angle (deg) | 25.94 ± 4.30 | 25.94 ± 4.30 | 25.95 ± 4.36 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) |

1.10 (0.99-1.21) |

0.15 (0.14-0.17) |

| Between-Image Data (n = 32) | ||||||

| Variable | Image 1 | Image 2 | Image 3 | ICC | %CV | TE |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | (90% CI) | (90% CI) | (90% CI) | |

| Muscle Thickness (cm) | 2.33 ± 0.31 | 2.36 ± 0.32 | 2.33 ± 0.31 | 0.95 | 2.98 | 0.45 |

| (0.92-0.97) | (2.51-3.45) | (0.38-0.54) | ||||

| Fascicle Length (cm) | 5.47 ± 1.15 | 5.57 ± 1.08 | 5.44 ± 1.08 | 0.89 | 6.09 | 0.69 |

| (0.82-0.93) | (5.10-7.08) | (0.60-0.84) | ||||

| Pennation Angle (deg) | 26.02 ± 4.28 | 25.66 ± 4.13 | 26.15 ± 4.63 | 0.83 | 6.22 | 0.85 |

| (0.73-0.90) | (5.05-7.39) | (0.74-1.03) | ||||

Note: SD = standard deviation, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient, CV = coefficient of variation, TE = typical error, and CI = confidence intervals

TABLE 2.

Descriptive and reliability statistics for between-session data (n = 22).

| Muscle Thickness (cm) |

Fascicle Length (cm) |

Pennation Angle (deg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 Mean ± SD | 2.42 ± 0.28 | 5.68 ± 1.04 | 25.88 ± 3.68 |

| Session 2 Mean ± SD | 2.45 ± 0.28 | 5.52 ± 1.03 | 26.99 ± 3.34 |

| ICC | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| (90% CI) | (0.78-0.94) | (0.89-0.97) | (0.86-0.97) |

| %CV | 3.30 | 3.52 | 3.64 |

| (90% CI) | (2.50-4.10) | (2.48-4.56) | (2.50-4.78) |

| SEM | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.93 |

| SDD | 0.26 | 0.64 | 2.58 |

| %SDD | 10.58 | 11.42 | 9.76 |

Note: SD = standard deviation, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient, CV = coefficient of variation, CI =confidence intervals, SEM = standard error of measurement, SDD = smallest detectible difference

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to determine the within-image, between-image and between-session reliability and SDD values of MG architectural properties (muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle) attained from ultrasound images recoded at rest and with MG fascicle length in full view. The ICC data show that very good-excellent reliability (ICCs = 0.83-1.00) was attained for each aspect of MG architecture across all levels of image analysis (Table 1 and Table 2). The corresponding CV data was also low (0.50-6.22%), which adds further confidence in the reliability of the reported measures (Table 1 and Table 2).

The within-image ICC and TE attained for the fascicle length and pennation angle measurements reported in this study (Table 1) are slightly better, but very similar, to the ICC value of 0.99 and TE values of 0.22 mm and 0.22° for fascicle length and pennation angle, respectively, reported in previous work [11]. Similarly, the between-session ICC and CV values are slightly better, although comparable, to the values of 0.81-0.97 and 3.53-5.47%, respectively, stated in a previous study [12]. The relative and absolute reliability data for the MG fascicle length in particular is better in the present study in comparison to values that have been reported previously [11, 12]. This may be attributable to the longer probe (100 mm) used in the current study which allowed for a complete measurement of MG fascicle length [14]. To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have reported between-image reliability values for the MG architectural properties of healthy adults and so comparisons at this level cannot be made. Nevertheless, the between-image reliability values reported here follow the similar trend of high reliability to those observed at the within-image and between-session level (Table 1 and Table 2).

Overall, the results of the present study suggest that reliable measures of MG architecture at rest can be attained using a combination of ultrasonography and image analysis. Although a recent study [16] found inter-rater reliability of MG architecture to be good-excellent (ICC = 0.77-0.90), it is recommended that a single rater both captures and analyzes MG ultrasound images due to the higher ICCs reported in the present study. Also, where possible, it is recommended that sonographic images of pennate skeletal muscle is recorded using a probe of sufficient proportions to allow for the capture of the entire fascicle length, given the previously reported underestimation [14] and greater within-image [11] and between-session [12] variability reported when using the linear extrapolation method. Further research into the effects of probe length and both intra- and inter-rater variability on architectural measurements of other commonly assessed muscles is also warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

Capturing and then manually digitizing ultrasound images of the MG muscle at rest yields highly reliable measurements of its architectural properties when conducted by a single rater and with a probe of sufficient length to image the entire fascicle. Furthermore, it is suggested that scientists and practitioners should only consider changes in MG muscle thickness, fascicle length and pennation angle of at least 10.6%, 11.4% and 9.8%, respectively, as meaningful when examining the effects of any form on intervention on these parameters. This will help to ascertain whether or not reported changes in MG architectural properties are meaningful or simply a product of the inherent error associated with these measurements.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blazevich A. Effects of physical training and detraining, immobilisation, growth and aging on human fascicle geometry. Sports Med. 2006;36(12):1003–17. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwah LK, Pinto RZ, Diong J, Herbert RD. Reliability and validity of ultrasound measurements of muscle fascicle length and pennation in humans: a systematic review. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114(6):761–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01430.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Secomb JL, Lundgren L, Farley ORL, Tran TT, Nimphius S, Sheppard JM. Relationships between lower-body muscle structure and lower-body strength, power and muscle-tendon complex stiffness. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;14(4):691–697. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earp JE, Kraemer WJ, Cormie P, Volek JS, Maresh CM, Joseph M, Newton RU. Influence of muscle-tendon unit structure on rate of force development during the squat, countermovement, and drop jumps. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(2):340–7. doi: 10.1519/jsc.0b013e3182052d78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball N, Scurr JC. Task and intensity alters the rms proportionality ratio in the triceps surae. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(6):890–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.24469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon JJ, Turner A, Comfort P. Relationships between lower body muscle structure and maximal power clean performance. J Trainology. 2015;4(2):32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckerman H, Roebroeck ME, Lankhorst GJ, Becher JG, Bezemer PD, Verbeek ALM. Smallest real difference, a link between reproducibility and responsiveness. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(7):571–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1013138911638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raj IS, Bird SR, Shield AJ. Reliability of ultrasonographic measurement of the architecture of the vastus lateralis and gastrocnemius medialis muscles in older adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32(1):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2011.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legerlotz K, Smith HK, Hing WA. Variation and reliability of ultrasonographic quantification of the architecture of the medial gastrocnemius muscle in young children. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2010;30(3):198–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohagheghi AA, Khan T, Meadows TH, Giannikas K, Baltzopoulos V, Maganaris CN. Differences in gastrocnemius muscle architecture between the paretic and non-paretic legs in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Clin Biomech. 2007;22(6):718–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer M, Seynnes O, di Prampero P, Pisot R, Mekjavić I, Biolo G, Narici M. Effect of 5 weeks horizontal bed rest on human muscle thickness and architecture of weight bearing and non-weight bearing muscles. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(2):401–7. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duclay J, Martin A, Duclay A, Cometti G, Pousson M. Behavior of fascicles and the myotendinous junction of human medial gastrocnemius following eccentric strength training. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39(6):819–27. doi: 10.1002/mus.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maganaris CN, Baltzopoulos V, Sargeant AJ. In vivo measurements of the triceps surae complex architecture in man: implications for muscle function. J Physiol. 1998;512(2):603–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.603be.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narici MV, Binzoni T, Hiltbrand E, Fasel J, Terrier F, Cerretelli P. In vivo human gastrocnemius architecture with changing joint angle at rest and during graded isometric contraction. J Physiol. 1996;496(1):287–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(1):98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.König N, Cassel M, Intziegianni K, Mayer F. Inter-Rater Reliability and Measurement Error of Sonographic Muscle Architecture Assessments. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33(5):769–77. doi: 10.7863/ultra.33.5.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]