Real-world data on coinfection are lacking. In this study, intention-to-treat sustained virological response rates were 76% for simeprevir/sofosbuvir, 94% for simeprevir/sofosbuvir/ribavirin, and 52% for sofosbuvir/ribavirin. Per protocol rates were 92% for simeprevir/sofosbuvir ± ribavirin.

Keywords: HIV, hepatitis C, simeprevir, sofosbuvir

Abstract

Background. Patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) with or without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) achieve high sustained virological response (SVR) rates on sofosbuvir (SOF)-containing regimens in clinical trials. Real world data on patients coinfected with HCV and HIV treated with SOF-based regimens are lacking.

Methods. This observational cohort study included HIV/HCV-coinfected adults with genotype 1 HCV who initiated treatment with a SOF-containing regimen between December 2013 and December 2014 (n = 89) at the Mount Sinai Hospital or the Brooklyn Hospital Center. The primary outcome was SVR at 12 weeks after the end of treatment. The secondary outcomes were risk factors for treatment failure, serious adverse events, and side effects. A post hoc per protocol analysis of SVR was performed on patients who completed treatment and follow-up.

Results. In an intention-to-treat analysis, SVR rates were 76% (31/41) for simeprevir (SMV)/SOF, 94% (16/17) for SMV/SOF/ribavirin (RBV), and 52% (16/31) for SOF/RBV. The SVR rates of SMV/SOF/RBV and SMV/SOF did not differ significantly in this small study (P = .15). However the SVR rate of SMV/SOF/RBV was higher than that of SOF/RBV (P < .01). In a per protocol analysis, SMV/SOF/RBV had a higher SVR rate than SOF/RBV: 100% (16/16) vs 57% (16/28) (P < .01). The most commonly reported adverse effects were rash, pruritus, fatigue, and insomnia. One patient who had decompensated cirrhosis prior to treatment initiation died after receiving SMV/SOF.

Conclusions. SMV/SOF ± RBV is an effective option with minimal adverse effects for most HIV-positive patients with genotype 1 HCV. SMV should be used with caution in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Approximately 10% of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected patients in the United States and Europe are coinfected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1–4]. Liver fibrosis progression is accelerated in coinfected patients with a detectable HIV viral load [5]. The goal of treatment is to induce a sustained virological response (SVR), meaning that the HCV viral load is undetectable at 12 weeks after the end of treatment. Use of combination direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has increased SVR rates to >90%. The use of DAAs and the elimination of interferon has significantly reduced adverse effects (AEs) and shortened treatment duration [6]. Ribavirin (RBV) has remained a part of some treatment regimens because it is pangenotypic, reduces relapse, and increases SVR rates, although it also causes a number of AEs such as hemolytic anemia, fatigue, and rash [6–8].

With interferon-based treatment, HIV/HCV-coinfected patients had lower SVR rates [9]. Since the advent of DAAs, coinfected patients have enjoyed relative parity in SVR rates [6, 7]. Sofosbuvir (SOF) is a once-daily HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HCV genotypes (GT) 1, 2, 3, and 4 [8, 10, 11]. Simeprevir (SMV) is a once-daily HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved for the treatment of HCV GT1 [8, 12]. Compared with the earlier protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, SMV has advantages of being a single pill taken once a day that causes fewer AEs [12–17].

Current American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD–IDSA) treatment guidelines are essentially identical for patients with HCV monoinfection and HIV/HCV coinfection [8]. An important consideration in the management of coinfected patients is the need to avoid drug–drug interactions (DDIs) between DAAs and antiretrovirals (ARVs), which may constrain the choice of HCV DAAs or require adjustment of the ARV regimen. First-line recommended regimens for GT1 HCV include daily fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir (LDV)/SOF, daily daclatasvir (DCV)/SOF, daily SMV/SOF ± weight-based RBV, and daily fixed-dose combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (3-D) with or without weight-based RBV. The AASLD–IDSA guidelines recommend the addition of RBV to 3-D in all GT1a patients and in cirrhotic GT1b patients [8]. SMV/SOF is the only DAA combination currently available in US and European markets that does not include an NS5A inhibitor, which may provide a particular utility in NS5A-resistant viruses. The phase 2 COSMOS study had SVR12 rates >90% in HCV GT1-monoinfected patients on SMV/SOF ± RBV for 12–24 weeks [13]. Although a recommended regimen, this combination has not yet been studied in an HIV/HCV-coinfected population. In this study, we compared the efficacy and safety of SMV/SOF with or without RBV to that of SOF/RBV in a real-world urban HIV/HCV-coinfected patient population.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This observational cohort study included all HCV/HIV-coinfected adults (aged ≥18 years) with HCV GT 1 who initiated treatment for HCV with a SOF-containing regimen between December 2013 and December 2014 at 2 sites in the New York metropolitan area: the Mount Sinai Hospital and the Brooklyn Hospital Center. All patients on SMV/SOF or SMV/SOF/RBV were placed on 12 week courses (the start of this study precedes the recommendation by the FDA for cirrhotics to receive 24 weeks of SMV-based DAA therapy.) All patients on SOF/RBV were placed on 24-week courses, per guidelines at the time. Electronic medical records were reviewed for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included the presence of impaired renal function (defined as creatinine clearance <30 mL/min as calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault equation), history of liver transplant, and treatment with a DAA other than SOF, SMV, and/or RBV. Advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis was defined as a Fibrosis 4 score ≥3.25 [18]. Data recorded included demographics, baseline medical conditions, ARV regimens, other medications, previous HCV treatment history, laboratory values, and AEs. If patients had prior treatment experience, only patients who had previously received interferon, RBV, TVR and/or BOC were included in the study. Patients with prior treatment experience with newer DAAs such as SOF, SMV, daclatasvir or ledipasvir were excluded. Laboratory values were collected at baseline, week 4, week 12, and at 12 weeks post-treatment and included white count, absolute neutrophil count, hemoglobin (Hgb), platelets, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, HCV RNA, HIV RNA, and fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score.

The primary endpoint was SVR12 (an undetectable HCV viral load 12 weeks post-treatment), analyzed on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis (ie, all patients who initiated treatment were included in the analysis). The HCV RNA in plasma was measured with the COBAS Taqman HCV/HPS v2.0 assay (Roche, Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, California; lower limit of quantification 25 IU/mL; limit of detection 15 IU/mL). The secondary outcomes included rates of relapse (return of HCV viremia after the end of treatment), treatment discontinuations after AEs, patient-reported side effects, and the percentage of patients in whom antiviral regimens were changed prior to initiating anti-HCV treatment to avoid DDIs.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher exact or χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. One-way analysis of variation (ANOVA) tests were used for continuous variables. If a statistically significant difference was found via ANOVA, then post hoc Bonferroni and Scheffé tests were performed between individual groups for the continuous variable in question. The primary analysis was done in the ITT population, which included all study participants. Patients lost to follow-up were considered to have virologic failure in the ITT analysis. The SVR rates of the SMV/SOF/RBV and SMV/SOF group were compared with that of the SOF/RBV group. An additional post hoc per protocol analysis was done that excluded patients who either discontinued treatment prematurely for nonvirological reasons or were lost to follow-up.

Data for coinfected patients were included in a multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors independently associated with SVR12. Factors known to influence SVR12 during anti-HCV therapy included age, sex, race (black vs other), previous treatment experience, body mass index, logarithm of HCV viral load, fibrosis stage (FIB-4 score <3.25 vs ≥3.25), CD4 count, and presence of a detectable HIV viral load. Variables with a P-value below .20 in the univariable analysis were forced into the multivariable model. Data were analyzed in SPSS (Chicago, Illinois, version 23). A P-value below .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

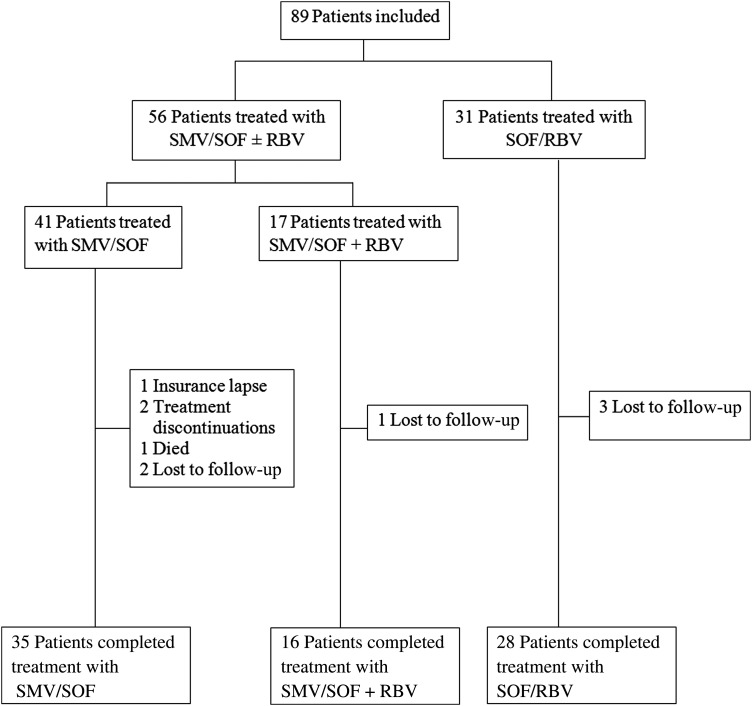

A total of 89 HIV/HCV-coinfected adults were included in the study (see Figure 1). The median age was 56 years (interquartile range, 51–61) and 38% (34/89) were black. The majority (74%) were infected with HCV GT1a, most (96%) were on ARV therapy and were male (78%). The treatment regimens for HCV were as follows: 41 patients (46%) received SMV/SOF, 17 (19%) received SMV/SOF/RBV, and 31 (35%) received SOF/RBV. Before starting SMV, ARV regimens were changed in 60% (33/55) of patients on SMV to avoid potential DDIs. Among these cases of patients who changed their ARV regimens, 73% (24/33) kept their new regimens for at least six months after completion of SMV-based therapy. No ARV changes were made for patients receiving SOF/RBV therapy (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart of hepatitis C virus treatment groups. Abbreviations: RBV, ribavirin; SMV, simeprevir; SOF, sofosbuvir.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Patient Characteristic | Total N = 89 (%) |

SMV/SOF N = 41 (%) |

SMV/SOF/RBV N = 17 (%) |

SOF/RBV N = 31 (%) |

SMV/SOF vs SMV/SOF/RBV P Value |

SMV/SOF vs SOF/RBV P Value |

SMV/SOF/RBV vs SOF/RBV P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male | 69 (78) | 29 (71) | 15 (88) | 25 (81) | .20 | .42 | .70 |

| Age, y | 56 (51–61) | 56 (51–59) | 56 (51–59) | 56 (51–61) | >.05 | >.05 | >.05 |

| Race, black | 34 (38) | 18 (44) | 5 (29) | 11 (36) | .39 | .63 | .76 |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 30 (34) | 21 (51)a | 4 (24) | 5 (16)a | .08 | <.01a | .70 |

| Cirrhosis (FIB-4 ≥ 3.25) | 41 (46) | 18 (44) | 7 (41) | 16 (52) | 1.00 | .64 | .56 |

| HCV VL (log IU/mL) | 6.39 (5.9–6.68) | 6.36 (6–6.66) | 6.46 (6.13–6.68) | 6.36 (5.9–6.66) | >.05 | >.05 | >.05 |

| HCV GT1a | 66 (74) | 28 (68)a | 17 (100)a | 21 (68)a | <.01a | 1.00 | <.01a |

| HCV GT1b | 23 (26) | 13 (32) | -- | 10 (32) | |||

| HCV treatment naive | 38 (43)a | 20 (49)a | 8 (47) | 10 (32) | 1.00 | .23 | .36 |

| HCV treatment experienced | 50 (56)a,b | 20 (49)a,b | 9 (53) | 21 (67) | 1.00 | .15 | .36 |

| PEG/RBV | 43 (48) | 19 (46) | 8 (47) | 16 (52) | 1.00 | .81 | 1.00 |

| TVR/PEG/RBV | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| BOC/PEG/RBV | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 2 (7) | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| CD4 count | 500 (221–831) | 564 (394–774) | 587 (483–831) | 348 (221–573) | >.05 | >.05 | >.05 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus VL (<20 copies/mL) | 68 (76) | 34 (83) | 13 (76) | 21 (68) | .72 | .17 | .74 |

| On ARV | 85 (96) | 39 (95) | 16 (94) | 30 (97) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ARV change required prior to starting Direct-acting antivirals | 27/39 (69)a | 6/16 (38)a | 0/30 (0)a | .04 | <.01a | <.01a | |

| ARV characteristics/regimens | |||||||

| Protease Inhibitor | 0 (0)a | 0 (0)a | 19 (63) | 1.00 | <.01a | <.01a | |

| Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | 16 (41) | 6 (38) | 8 (27) | 1.00 | .31 | .51 | |

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | 39 (100) | 16 (100) | 29 (97) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Tenofovir | 34 (87) | 14 (88) | 21 (70) | 1.00 | .13 | .06 | |

| Abacavir | 10 (26) | 3 (19) | 3 (10) | .73 | .13 | .65 | |

| Integrase inhibitor | 24 (62) | 11 (69) | 13 (43) | 1.00 | .15 | .13 | |

For categorical data, Fisher exact test was used to calculate P values, 2-tailed.

For continuous data, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. If a statistically significant difference between groups was found using ANOVA, post hoc Bonferroni and Scheffé tests were performed to calculate P values.

Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral therapy; BOC, boceprevir; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; Gt, genotype; HCV VL, hepatitis C virus viral load (log IU/ml); PEG, pegylated interferon; RBV, ribavirin; SMV, simeprevir; SOF, sofosbuvir; TVR, telaprevir.

a Denotes a statistically significant difference between at least two different treatment groups.

b One patient in the SMV/SOF group could not be determined as having treatment experience or not.

According to the ITT analysis, 71% (63/89) achieved SVR12 (see Table 2). The SVR12 rate was 76% (31/41) for SMV/SOF, 94% (16/17) for SMV/SOF/RBV, and 52% (16/31) for SOF/RBV. The SVR12 rate was higher for SMV/SOF ± RBV than for SOF/RBV: 81% vs 52%, respectively (P < .01). Although the SVR12 rate was higher for SMV/SOF/RBV vs SMV/SOF, 94% vs 76% (P = .15), respectively, statistical significance was not reached.

Table 2.

Sustained Virologic Response 12 Weeks After Completion of Direct-acting Antiviral Therapy Rates for Sofosbuvir-Containing Regimens

| SVR12 Rate | All Patients N (%) |

SMV/SOF N (%) |

SMV/SOF/RBV N (%) |

SOF/RBV N (%) |

SMV/SOF vs SMV/SOF/RBV P Values |

SMV/SOF vs SOF/RBV P Values |

SMV/SOF/RBV vs SOF/RBV P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per protocol | 63/79 (80) | 31/35 (89) | 16/16 (100) | 16/28 (57) | .30 | <.01 | <.01 |

| Intention to treat | 63/89 (71) | 31/41 (76) | 16/17 (94) | 16/31 (52) | .15 | .05 | <.01 |

| Treatment naive | 28/38a (74) | 15/20 (75) | 7/8 (88) | 6/10 (60) | .64 | .43 | .31 |

| Treatment experienced | 34/50a (83) | 15/20 (75) | 9/9 (100) | 10/21 (48) | .15 | .11 | .01 |

| Cirrhosis | 26/41 (63) | 11/18 (61) | 6/7 (86) | 9/16 (56) | .36 | 1.00 | .34 |

| No cirrhosis | 37/48 (77) | 20/23 (87) | 10/10 (100) | 7/15 (47) | .54 | .01 | <.01 |

For categorical data, Fisher exact test was used to calculate P values, 2-tailed.

Abbreviations: RBV, ribavirin; SMV, simeprevir; SOF, sofosbuvir; SVR12, sustained virologic response 12 weeks after completion of direct-acting antiviral therapy.

a One patient could not be determined as having treatment experience or not.

In a univariable logistic regression analysis (see Table 3), treatment with an SMV-containing regimen was positively associated with achievement of SVR12 (SMV/SOF vs SOF/RBV: odds ratio [OR] = 2.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–7.92 and SMV/SOF/RBV vs SOF/RBV: OR = 15; 95% CI, 1.77–127.44). In the multivariable model, SMV/SOF compared with SOF/RBV failed to be positively associated with SVR12 (OR = 2.26; 95% CI, .77–6.66). However, SMV/SOF/RBV compared with SOF/RBV maintained a positive association with SVR12 in the multivariable model (OR = 18.22; 95% CI, 2–165.87). If SMV/SOF was used as the reference regimen, SMV/SOF/RBV trended toward significance for acquisition of SVR12 in univariable analysis (OR = 5.16; 95% CI, .6–43.97; P = .13) and in multivariable analysis (OR = 8.15; 95% CI, .84–79.39; P = .071) (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Analysis With Sustained Virologic Response 12 Weeks After Completion of Direct-acting Antiviral Therapy as the Outcome With Sofosbuvir/Ribavirin as the Reference Regimen

| Factors | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Drug | ||||||

| SOF/RBV | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| SMV/SOF | 2.91 | 1.07–7.92 | .04 | 2.26 | .77–6.66 | .14 |

| SMV/SOF/RBV | 18.22 | 1.77–127.44 | .013 | 18.22 | 2–165.87 | .01 |

| Age, years | 0.99 | .94–1.05 | .82 | … | … | … |

| Gender, female | 2.83 | .75–10.67 | .12 | 2.88 | .71–11.7 | .14 |

| Race, black | 0.99 | .39–2.52 | .97 | … | … | … |

| HCV subgenotype 1a | 0.6 | .2–1.82 | .36 | … | … | … |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.03 | .95–1.13 | .43 | … | … | … |

| Naive to treatment | 1.28 | .5–3.26 | .6 | … | … | … |

| CD4 < 200 | 0.30 | .055–1.62 | .3 | … | … | … |

| HIV<20 copies/mL | 1.67 | .49–5.65 | .41 | … | … | … |

| FIB-4 score ≥3.25 | 0.52 | .2–1.3 | .16 | 0.92 | .25–3.39 | .91 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.12 | .87–1.44 | .39 | … | … | … |

| Platelet (103/µL) | 1.01 | .99–1.01 | .13 | 1.00 | .99–1.01 | .8 |

| HCV viral load (log IU/mL) | 0.92 | .41–2.05 | .84 | … | … | … |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 1.00 | .99–1.01 | .56 | … | … | … |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 0.99 | .98–1 | .077 | 0.99 | .98–1.01 | .25 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.77 | .47–1.27 | .77 | … | … | … |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.5 | .67–3.38 | .33 | … | … | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio; RBV, ribavirin; REF, reference regimen; SMV, simeprevir; SOF, sofosbuvir.

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Analysis With Sustained Virologic Response 12 Weeks After Completion of Direct-acting Antiviral Therapy as the Outcome With Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir Adjusted as the Reference Drug Regimen

| Factors | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Drug | ||||||

| SMV/SOF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| SOF/RBV | 0.344 | .13–.94 | .04 | 0.45 | .15–1.33 | .15 |

| SMV/SOF/RBV | 5.16 | .6–43.97 | .13 | 8.15 | .84–79.39 | .071 |

| Age, y | 0.99 | .94–1.05 | .82 | … | … | … |

| Gender, female | 2.83 | .75–10.67 | .12 | 2.95 | .73–12 | .13 |

| Race, black | 0.99 | .39–2.52 | .97 | … | … | … |

| HCV subgenotype, 1a | 0.6 | .2–1.82 | .36 | … | … | … |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.03 | .95–1.13 | .43 | … | … | … |

| Naive to treatment | 1.28 | .5–3.26 | .6 | … | … | … |

| CD4 < 200 | 0.30 | .055–1.62 | .3 | … | … | … |

| HIV<20 copies/mL | 1.67 | .49–5.65 | .41 | … | … | … |

| FIB-4 score ≥3.25 | 0.52 | .2–1.3 | .16 | 0.87 | .24–3.2 | .84 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.12 | .87–1.44 | .39 | … | … | … |

| Platelet (103/µL) | 1.01 | .99–1.01 | .13 | 1.00 | .99–1.01 | .9 |

| HCV viral load (log IU/mL) | 0.92 | .41–2.05 | .84 | … | … | … |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 1.00 | .99–1.01 | .56 | … | … | … |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 0.99 | .98–1 | .077 | 0.99 | .98–1.01 | .26 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.77 | .47–1.27 | .77 | … | … | … |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.5 | .67–3.38 | .33 | … | … | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio; RBV, ribavirin; REF, reference regimen; SMV, simeprevir; SOF, sofosbuvir.

Of the 11 SMV/SOF ± RBV treatment failures in the ITT analysis, 1 patient with cirrhosis who was Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class C prior to treatment died after treatment with SMV/SOF. Approximately 6 weeks into treatment, the patient developed worsening ascites and a peritoneal fluid cell count consistent with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (cultures were negative). The patient was admitted for intravenous antibiotics. SMV was discontinued at the time of hospitalization. The patient continued on SOF with the addition of RBV and was discharged shortly afterward. Several weeks later, the patient was readmitted to the intensive care unit and later died of a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli sepsis, presumably due to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Among the other patients who did not achieve an SVR on an SMV-based regimen, 3 discontinued treatment prior to completion of 12 weeks of therapy. Two of these 3 patients had serious AEs while on medication. The first developed severe abdominal pain and vomiting after taking the initial dose of SMV/SOF. The second patient developed lip swelling and new-onset lower extremity edema with full-body hyperpigmentation after initiating a new antihypertensive agent; this took place during treatment week 4. It is unclear as to whether these adverse events were related to SMV or SOF. The third patient who discontinued treatment early lost his insurance mid-treatment and only completed 8 weeks of therapy. Three other patients were lost to follow-up.

There were 4 virologic treatment relapses among the patients on SMV/SOF ± RBV (Table 5). AEs were assessed at each visit. Rash, pruritus, and fatigue were common complaints among the patients included in the study (see Table 6). Only one patient in the SMV/SOF group (1/41, 2%) had HIV virologic failure during HCV treatment with an HIV virologic load that increased to 3658 copies/ml. The patient developed confirmed mutations to his HIV regimen which consisted of tenofovir, emtricitabine and rilpivirine. Despite HIV virologic failure, the patient achieved SVR12.

Table 5.

Virologic Relapses Among Patients Who Completed a Full 12 Weeks of Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir

| VR Case | FIB-4 > 3.25 | Treatment Experienced | Q80K | Baseline HCV VL | On ARVs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 4 163 901 | Yes |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Unknown | 3 056 562 | Yes |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | Unknown | 569 980 | No |

| 4 | Yes | No | Unknown | 778 023 | Yes |

Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral therapy; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; HCV VL, hepatitis C virus viral load (IU/mL); VR, virologic relapse.

Table 6.

Treatment-emergent Adverse Effects and Selected Laboratory Abnormalities

| Adverse Effect | Total N = 89 |

SMV/SOF N = 41 |

SMV/SOF/RBV N = 17 |

SOF/RBV N = 31 |

SMV/SOF vs SMV/SOF/RBV P Values |

SMV/SOF vs SOF/RBV P Values |

SMV/SOF/RBV vs SOF/RBV P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rash | 23 (26%) | 5 (12%) | 7 (41%) | 11 (36%) | .03 | .02 | .76 |

| Pruritus | 16 (18%) | 5 (12%) | 6 (35%) | 5 (16%) | .07 | .73 | .16 |

| Fatigue | 24 (27%) | 2 (5%) | 7 (41%) | 15 (48%) | <.01 | <.01 | .77 |

| Insomnia | 23 (26%) | 3 (7%) | 6 (35%) | 14 (45%) | .01 | <.01 | .56 |

| Anxiety | 12 (14%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (18%) | 6 (19%) | .35 | .16 | 1.00 |

| Decreased appetite | 9 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (18%) | 5 (16%) | .07 | .07 | 1.00 |

| Arthralgia | 9 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (18%) | 5 (16%) | .07 | .07 | 1.00 |

| Hemoglobin drop by >2 g/dL | 19 (21%) | 2 (5%) | 4 (24%) | 13 (42%) | .06 | <.01 | .34 |

| Neutropenia on therapy (absolute neutrophil count < 1000) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (7%) | 1.00 | .18 | .53 |

| Total bilirubin rise of >2 mg/dL | 9 (10%) | 3 (16%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (11%) | 1.00 | .28 | .40 |

For categorical data, Fisher exact test was used to calculate P values, 2-tailed.

Abbreviations: RBV, ribavirin; SMV, simeprevir; SOF, sofosbuvir.

DISCUSSION

This observational cohort provides the first information about the efficacy of SMV/SOF ± RBV in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. SMV/SOF is an effective option with minimal adverse effects for most HIV-positive patients with HCV GT1. Pending further data, SMV should be used with caution in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, which is consistent with package insert recommendations against the use of SMV in CTP B or C [12]. Although SMV may have significant DDIs with ARVs, SMV/SOF ± RBV may continue to be a valuable option in patients who have failed NS5A inhibitor–based regimens.

Our study had important strengths and some limitations. The strengths include the information it provides about the effectiveness of SMV- and/or SOF-based therapies outside clinical trials and the likely generalizability of the results to other real-world settings. The main limitations are the small sample size, lack of patients with known NS5A resistance mutations, the fact that the study began prior to the FDA's recommendation to extend SMV-based DAA therapy to 24 weeks for cirrhotic patients, and use of FIB-4 scores to determine cirrhosis instead of transient elastography or biopsies. Data about HIV parameters such as CD4 count and viral load were not always available. IL28b polymorphisms and Q80K mutations were unknown for most patients.

The combination of SMV/SOF was generally well tolerated in our study. Patients placed on an SMV-containing regimen had a statistically significant difference in outcome compared with those in the SOF/RBV group. Our real-world experience with SOF/RBV for 24 weeks had an SVR rate of 52%, which is lower than the 76% SVR reported in the PHOTON study [10].

In the ITT analysis of our cohort, 81% (47/58) of patients on SMV/SOF ± RBV achieved SVR12. This SVR12 rate was comparable to the SVR12 rates seen in the COSMOS clinical trial (154/167, 92%) [13] and the real-world data in the HCV-TARGET (850/956, 89%) [19] and TRIO (263/317, 83%) studies [20]. Per protocol analyses are available for the COSMOS and TRIO studies. The per protocol SVR12 rates were 96% (152/158) in COSMOS [13] and 90% (263/292) in TRIO [20]. The per protocol SVR12 rate in our study was comparable at 92% (47/51), indicating that the efficacy of SMV/SOF ± RBV can be generalized to the coinfected population.

Of interest, the addition of RBV to SMV/SOF trended toward significance (P = .15) in the per protocol population. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, if SMV/SOF was set as the reference regimen, SMV/SOF/RBV trended toward statistical significance for acquisition of SVR12 (OR = 8.15; 95% CI, .84–79.39; P = .071) but failed to achieve a P value less than .05 (see Table 4). Given the small number of patients in the SMV/SOF/RBV arm (n = 17 in the ITT population), it is difficult to comment on whether or not RBV has any meaningful impact on the SVR12 rate. Data from previous studies such as COSMOS and HCV-TARGET involving SMV/SOF-monoinfected patients do not demonstrate a significant difference in SVR12 rates between patients treated with RBV and those treated without RBV [13, 19]. Given these findings, the AASLD–IDSA guidelines do not recommend the routine use of RBV in SMV/SOF regimens [8]. Nevertheless, in the modern era, RBV still has a role in other DAA regimens. For example, the guidelines recommend that RBV be used with 3-D for the treatment of GT1 disease in all circumstances, except in the case of noncirrhotic GT 1b patients, due to improved outcomes in SVR12 rates from clinical trials [8, 21–24]. The addition of RBV to SOF/LDV shortens the recommended length of therapy from 24 weeks to 12 weeks in cirrhotic treatment-experienced GT1 monoinfected patients, based on equivalent outcomes in clinical trials [25, 26].

A 12-week course of SMV/SOF is rather costly, in excess of $160 000 [27], as opposed to 12 weeks of SOF/DCV at $147 000 [28], 12 weeks of SOF/LDV at $94 000 [28, 29], or 12 weeks of 3-D at $84 000 [28]. According to the AASLD–IDSA guidelines [8], patients with cirrhosis and/or treatment experience must often be placed on 24 weeks of DAAs, such as SOF/DCV, SOF/LDV, 3-D, and SMV/SOF. Again, it would be useful to have more data among difficult-to-treat HCV patients placed on 12 weeks of SMV/SOF/RBV to see if the addition of RBV led to SVR12 rates equivalent or superior to those obtained from 24-week courses of DAAs. In that case, 12 weeks of SMV/SOF/RBV would be less costly than 24 weeks of the other currently available DAA regimens.

Aside from cost, there may be a niche where SMV/SOF can be useful. Data from recent conferences show that there is a significant amount of baseline and acquired resistance to NS5A inhibitors such as LDV, DCV, and elbasvir. In a presentation by Zeuzem et al, treatment-naive GT1a monoinfected patients treated with an investigational NS3/4A protease inhibitor and NS5A inhibitor grazoprevir/elbasvir had an SVR12 of 99% if there were no baseline NS5A resistance-associated variants (RAVs) [30]. However, in those patients with NS5A RAVs that were considered to have >5-fold potency loss, the SVR12 rate was 22%. A similarly markedly decreased SVR12 rate was seen by Wyles et al in a cohort that included GT1 patients who had previously failed SOF/LDV and were retreated with SOF/LDV for 24 weeks [31]. Patients with only 1 baseline NS5A RAV achieved an SVR12 of 69%, whereas those with 2 or more RAVs achieved a reduced SVR12 of 50% [31]. Of greater concern is the persistence of the NS5A RAVs. Ninety-seven percent of patients who failed 3-D had RAVs at post-treatment week 24 and 96% of them retained those RAVs at post-treatment week 48 [32]. SMV/SOF has been studied in the treatment of patients who previously failed DCV-based regimens. The results of this pilot study showed 83% and 100% SVR12 rates in patients with and without NS5A RAVs, respectively [33]. In all, persistent acquired NS5A resistance may pose a challenge for retreatment and suggests a potential for SMV/SOF to emerge as an attractive option.

In our study, AEs such as pruritus, rash, and fatigue were infrequently reported (see Table 6). Two of 58 patients (3.4%) on SMV/SOF ± RBV discontinued therapy due to AEs compared with 2% in the COSMOS study [13].

Because the liver predominantly metabolizes SMV, SMV concentrations can rise in the setting of moderate-to-severe cirrhosis, increasing the risk of AEs [12]. The combined AASLD–IDSA guidelines recommend against the use of SMV in decompensated cirrhosis due to a lack of data [8] and its use in CTP B and C cirrhotics is contraindicated in the prescribing information [12]. At the time of this writing, there was some limited data related to the safety of SMV in decompensated monoinfected cirrhotics. Saxena et al [34] did not show an increased rate of decompensation when 55 CTP B and C chronic HCV-infected patients treated with SMV/SOF were compared to cirrhotic control cases not on DAAs. Modi et al reported data on 35 CTP B and 7 CTP C monoinfected patients (n = 42) placed on SMV/SOF ± RBV for 12 weeks [35]. Treatment was well tolerated, with 57% (24/42) of participants reporting no severe adverse events. There were no episodes of decompensation requiring hospitalization nor were there any deaths. While these data are reassuring, 1 patient died in our study. Therefore, we contend that SMV should be used with caution in the setting of decompensated cirrhosis (CTP B and C).

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides the first information about the efficacy of SMV/SOF ± RBV in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. SMV/SOF is an effective and safe option with minimal adverse effects for most HIV-positive patients with HCV GT1. Pending further data, SMV should be used with caution in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health (DA031095, DK090317).

Potential conflicts of interest. D. D. B. has been an investigator for several Gilead Sciences studies. A. C. has served on advisory boards for Gilead Sciences and Janssen Therapeutics. K. B. has been a consultant for Gilead Sciences and Janssen Therapeutics. A. H. has been a consultant for Gilead Sciences and Janssen Therapeutics. J. O. has been an investigator for several Gilead Sciences studies. T. D. S. has been an investigator for several Gilead Sciences studies. He has received research support from Gilead Sciences as well. P. V. P. has received research support from Gilead Sciences. D. T. D. has been a consultant and scientific advisor for Gilead Sciences. A. D. B. has received research support from Gilead Sciences. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Alberti A, Clumeck N, Collins S et al. Short statement of the first European Consensus Conference on the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C in HIV co-infected patients. J Hepatol 2005; 42:615–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34:831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockstroh JK, Mocroft A, Soriano V et al. Influence of hepatitis C virus infection on HIV-1 disease progression and response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:992–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin J, Kaye M, Skidmore S, Pillay D, Cooper DA, Dore GJ. HIV and hepatitis C coinfection within the CAESAR study. HIV Med 2004; 5:174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulkowski MS, Mehta SH, Torbenson MS et al. Rapid fibrosis progression among HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infected adults. AIDS 2007; 21:2209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockstroh JK. Optimal therapy of HIV/HCV co-infected patients with direct acting antivirals. Liver Int 2015; 35(suppl 1):51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Bello D, Nagy FI, Hand J et al. Direct-acting antiviral-based therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus in HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015; 10:337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) IDSoAIatIAS-UI-U. 2014 Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Available at: wwwhcvguidelinesorg. Accessed 16 October 2015.

- 9.Torriani FJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rockstroh JK et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:438–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulkowski MS, Naggie S, Lalezari J et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients with HIV coinfection. JAMA 2014; 312:353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina JM, Orkin C, Iser DM et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus in patients co-infected with HIV (PHOTON-2): a multicentre, open-label, non-randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet 2015; 385:1098–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; November, 2014. Available at: http://www.olysio.com/shared/product/olysio/prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed 16 October 2015.

- 13.Lawitz E, Sulkowski MS, Ghalib R et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, to treat chronic infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in non-responders to pegylated interferon and ribavirin and treatment-naive patients: the COSMOS randomised study. Lancet 2014; 384:1756–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotte L, Braun J, Lascoux-Combe C et al. Telaprevir for HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients failing treatment with pegylated interferon/ribavirin (ANRS HC26 TelapreVIH): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martel-Laferriere VBS, Bichoupan K, Posner S et al. On-treatment and sustained virologic response rates of telaprevir-based HCV treatments do not differ between HIV/HCV coinfected and HCV monoinfected patients In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 3–6 March 2013; Atlanta, GA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulkowski MS, Sherman Ke, Dieterich DT et al. Combination therapy with telaprevir for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in patients with HIV: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159:86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulkowski M, Pol S, Mallolas J et al. Boceprevir versus placebo with pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in patients with HIV: a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2007; 46:32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxena VFF, Sise M, Lim JK et al. Safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in hepatitis C infected patients with reduced renal function: real-world experience from HCV-TARGET In: 50th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver; 22–26 April 2015; Vienna, Austria 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dieterich DTBB, Flamm S, Kowdley K et al. Final evaluation of HCV patients treated with 12 week sofosbuvir +/- simeprevir regimens in the TRIO network: academic and community treatment of a real-world, heterogeneous population In: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Boston, MA 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1983–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1973–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sulkowski MS, Eron JJ, Wyles D et al. Ombitasvir, paritaprevir co-dosed with ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients co-infected with HIV-1: a randomized trial. JAMA 2015; 313:1223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourliere M, Bronowicki J, de Ledinghen et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir fixed dose combination is safe and efficacious in cirrhotic patients who have previously failed protease-inhibitor based triple therapy In: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; 7–11 November 2014; Boston, MA 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourliere MSM, Omata M, Zeuzem S et al. An integrated safety and efficacy analysis of >500 patients with compensated cirrhosis treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin In: American Association of the Study of Liver Diseases; 7–11 November 2014; Boston, MA 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bichoupan KTN, Yalamanchili R, Patel N et al. Real-world pharmaceutical costs in the simeprevir/sofosbuvir era $164,685 per SVR 4 In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 23–26 February 2015; Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stahmeyer JT, Rossol S, Krauth C. Outcomes, costs and cost-effectiveness of treating hepatitis C with direct acting antivirals. J Comp Eff Res 2015; 4:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Younossi ZM, Park H, Saab S, Ahmed A, Dieterich D, Gordon SC. Cost-effectiveness of all-oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41:544–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeuzem SGR, Reddy KR, Pockros PJ et al. The phase 3 C-EDGE treatment-naive study of a 12-week oral regimen of grazoprevir (MK-5172)/elbasvir (MK-8742) in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1,4 or 6 infection In: European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL); 22–26 April 2015; Vienna, Austria 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyles DL, Pockros PJ, Yang JC et al. Retreatment of patients who failed prior sofosbuvir-based regimens with all oral fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks In: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; 7–11 November 2014; Boston, MA 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnan PTR, Schnell G, Reisch T et al. Long-term follow-up of treatment-emergent resistance-associated variants in NS3, NS5A, NS5B with paritaprevir/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir-based regimens In: European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; 22–26 April 2015; Vienna, Austria 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hezode CCS, Scoazec G, Bouvier-Alias M et al. Retreatment with an interferon-free combination of simeprevir-sofosbuvir in patients who had previously failed on HCV NS5A inhibitor-based regimens In: European Meeting on HIV and Hepatitis; 3–5 June 2015; Barcelona, Spain 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saxena V, Nyberg L, Pauly M et al. Safety and efficacy of simeprevir/sofosbuvir in hepatitis C-infected patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatology 2015; 62:715–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Modi AA, Nazario H, Trotter JF et al. Safety and efficacy of simeprevir plus sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin in patients with decompensated genotype 1 hepatitis C cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 2016; 22:281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.