Daptomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 3–4 µg/mL often harbor mutations associated with daptomycin resistance. In a multicenter retrospective study, daptomycin MICs of 3–4 µg/mL in E. faecium predicted prolonged time to clearance in bacteremia.

Keywords: E. faecium, daptomycin, MIC, bloodstream infection, resistance

Abstract

Background. Daptomycin has become a front-line antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium bloodstream infections (BSIs). We previously showed that E. faecium strains with daptomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in the higher end of susceptibility frequently harbor mutations associated with daptomycin resistance. We postulate that patients with E. faecium BSIs exhibiting daptomycin MICs of 3–4 µg/mL treated with daptomycin are more likely to have worse clinical outcomes than those exhibiting daptomycin MICs ≤2 µg/mL.

Methods. We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study that included adult patients with E. faecium BSI for whom initial isolates, follow-up blood culture data, and daptomycin administration data were available. A central laboratory performed standardized daptomycin MIC testing for all isolates. The primary outcome was microbiologic failure, defined as clearance of bacteremia ≥4 days after the index blood culture. The secondary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality.

Results. A total of 62 patients were included. Thirty-one patients were infected with isolates that exhibited daptomycin MICs of 3–4 µg/mL. Overall, 34 patients had microbiologic failure and 25 died during hospitalization. In a multivariate logistic regression model, daptomycin MICs of 3–4 µg/mL (odds ratio [OR], 4.7 [1.37–16.12]; P = .014) and immunosuppression (OR, 5.32 [1.20–23.54]; P = .028) were significantly associated with microbiologic failure. Initial daptomycin dose of ≥8 mg/kg was not significantly associated with evaluated outcomes.

Conclusions. Daptomycin MICs of 3–4 µg/mL in the initial E. faecium blood isolate predicted microbiological failure of daptomycin therapy, suggesting that modification in the daptomycin breakpoint for enterococci should be considered.

Enterococci are gram-positive cocci that are normal commensals of the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals. These organisms are best known for their ability to cause recalcitrant and difficult-to-manage infections in the hospital environment and are among the top 5 leading bacterial causes of healthcare-associated infections in the United States [1, 2]. Although more than 10 enterococcal species are known to cause human disease, the 2 most common species isolated from clinical samples are Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium [1].

The treatment of severe enterococcal infections is complicated by resistance to multiple antimicrobials [3]. Optimal cure rates in serious enterococcal infections have generally been achieved only by combining a β-lactam or a glycopeptide with an aminoglycoside. However, particularly in the United States, glycopeptides and β-lactams have become almost obsolete for the treatment of E. faecium infections [4–6]. Moreover, an increase in the frequency of isolation and spread of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in hospitals around the world has been correlated with the emergence and dissemination of a specific E. faecium genetic clade worldwide that harbors multiple antibiotic-resistance determinants [7]. Additionally, several studies have now shown that the presence of vancomycin resistance in enterococci is strongly associated with worse clinical outcomes, including significantly higher mortality [8], longer length of stay, and higher direct medical costs [9] when compared with sensitive strains.

As a result, clinicians are often left with few options to treat recalcitrant VRE infections. Quinupristin/dalfopristin (Q/D) and linezolid are among the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved compounds for the treatment of VRE. However, Q/D lost this approval in 2010 [10] because clinical benefit could not be verified. Linezolid is bacteriostatic, and its efficacy for severe VRE infections has been recently questioned in a large retrospective cohort study within the Veterans Affairs system, which showed higher failure rates with linezolid [11]. This issue along with concerns over the safety profile and low serum concentrations limit the prolonged use of linezolid.

Daptomycin is a lipopeptide antibiotic with potent in vitro bactericidal activity against VRE. It has become a key first-line antibiotic for severe enterococcal infections despite lacking FDA approval for this indication. Daptomycin-mediated bacterial killing is concentration-dependent, and a therapeutic strategy suggested for the treatment of deep-seated enterococcal infections is the use of doses that are higher than those approved for Staphylococcus aureus infections. Indeed, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), the current daptomycin breakpoint for enterococci (4 μg/mL) is 4-fold higher than that for staphylococci (1 μg/mL). However, a drawback for the successful use of daptomycin for recalcitrant enterococcal infections is the emergence of daptomycin resistance. Daptomycin resistance appears to emerge during therapy [12, 13] but has also been described as a de novo phenomenon in isolates that have never been exposed to the antibiotic [14].

We and others have provided compelling data that the in vitro daptomycin bactericidal activity is compromised in isolates with a daptomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) that is close to the breakpoint (3–4 μg/mL) [15, 16]. Indeed, such E. faecium isolates often harbor mutations associated with daptomycin resistance. Moreover, we recently reported a case [17] of a patient with persistent E. faecium bacteremia for 3 months whose initial isolate exhibited a daptomycin MIC of 3 μg/mL and harbored mutations in genes often associated with daptomycin resistance (liaFSR, encoding a bacterial 3-component regulatory system that is predicted to orchestrate the bacterial cell membrane response to stress).

Here, we sought to examine the clinical outcomes for patients with enterococcal bacteremia and infected with daptomycin-“susceptible” E. faecium isolates with MICs of 3–4 μg/mL compared with isolates with MICs of ≤ 2 μg/mL and treated with daptomycin as the initial regimen. We postulated that E. faecium isolates that exhibit MICs to daptomycin of 3–4 µg/mL (ie, “susceptible” by CLSI breakpoints) and that are treated with daptomycin may have significantly worse clinical outcomes compared with isolates with lower MICs.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Design and Clinical Investigation

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study from February 2010 through February 2015. The primary criteria for inclusion were nonpregnant adult patients aged >18 years, blood culture positive for E. faecium with availability of the first clinical isolate for laboratory study, treatment with daptomycin for at least 72 hours, and collection of at least 1 follow-up blood culture within 7 days of identification of initial bacterial isolate from blood (an absolute requirement to define microbiologic cure). Patients who had E. faecium isolates with daptomycin MIC > 4 µg/mL and patients who received daptomycin after a negative follow-up culture were excluded (ie, patients who started daptomycin after the first negative follow-up blood culture was drawn). Four geographically separated institutions participated in this study and included Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan; MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas; University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville; and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. The respective institutional review boards of each participating institution approved this study.

Clinical information that prior studies have used to define patient condition at the time of diagnosis [18, 19] in 5 areas was collected and included the following: demographics such as age, sex, and day of hospitalization; immunity and major organ function (cardiac, hepatic, and renal function), including use of immunosuppressive therapies (mycophenolate, tacrolimus, biologics, and other nonsteroidal immunosuppressants) and chemotherapeutic medications (given within 2 weeks prior to index culture) and/or neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1000 cells/µL) within 2 weeks of index culture; baseline comorbid illnesses as outlined by the Charlson comorbidity index [20]; concurrent antibiotic therapies and those given within 2 weeks of blood culture targeting enterococci such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides, linezolid, quinupristin/dalfopristin, tigecycline, vancomycin, and daptomycin; and identification of sources of infection including abscesses, central lines, and endocarditis.

We defined the following 3 major outcomes of interest for which data were collected: microbiologic failure, in-hospital all-cause mortality, and disease relapse. Microbiologic failure was defined as clearance occurring 4 or more days after index blood culture that included at least 72 hours of daptomycin therapy or if the patient expired with persistently positive cultures. The cutoff value of 4 days was chosen since the mean and median times to clearance were both around 4 days. In-hospital all-cause mortality referred to death occurring from any cause during admission. This definition was preferred to 30-day mortality in order to minimize confounding from follow-up as not all centers consistently documented out-of-hospital mortality. Finally, relapse was defined as positive cultures within 30 days of index culture occurring after documented clearance.

Laboratory Investigations

Microbiologic data provided by the clinical laboratories were collected, including the antibiotic sensitivities reported from the initial and subsequent blood cultures (when available). Initial bacterial isolates recovered from all patients were sent for further analysis to the University of Texas Medical School, Houston. For each index bloodstream isolate, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to confirm E. faecium species was performed [21]. Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l′Etoile, France) was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar following the manufacturer's instructions. Two independent and experienced investigators interpreted MICs; a third investigator was consulted when a disagreement occurred. Broth microdilution was completed using Mueller Hinton II broth (Becton, Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) supplemented with calcium (50 µg/mL) [22, 23]. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was carried out to assess for a genetic relationship between isolates, as described [24]. All laboratory investigators who participated in conducting E-test, PCR, and PFGE analysis were blinded to the clinical patient data associated with each isolate.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons of the 5 areas defining the patient's baseline severity of illness were assessed using the χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables with significance attributable at P < .05. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the relationship between MIC of the index isolate and/or clinical characteristics defining baseline severity of illness with the outcomes of interest (microbiological clearance, in-hospital mortality, and relapse). Subsequently, variables with P < .05 were selected for multivariate analysis via a logistic regression model with the outcomes of clearance and death. The goodness-of-fit of the final model was examined using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Bootstrap analysis was done to internally validate the logistic regression models. All statistical analyses were completed using SPSS for Mac version 21 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

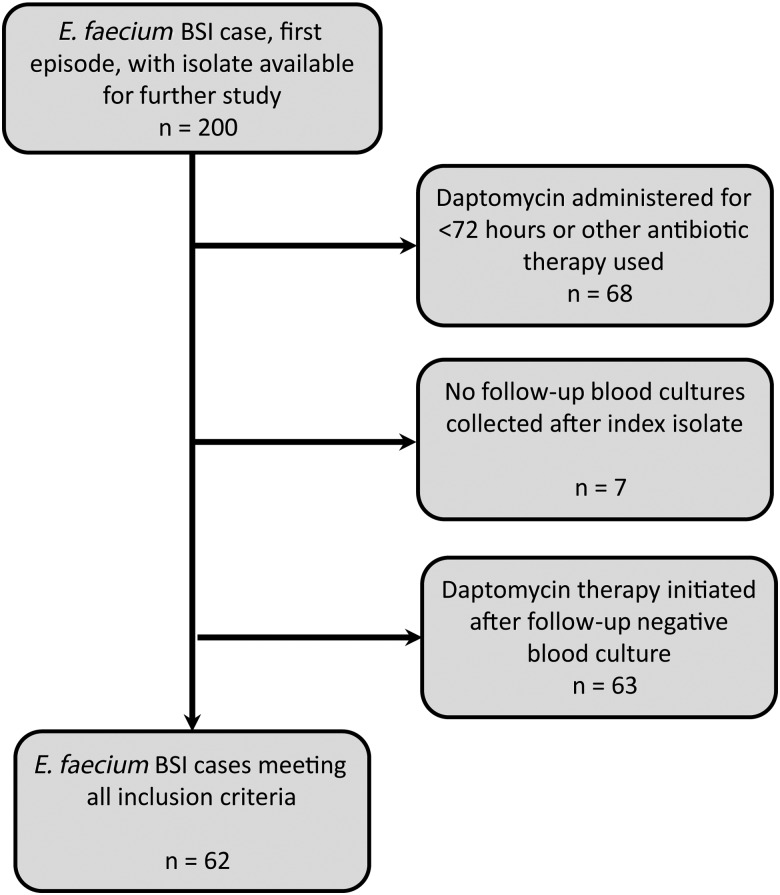

A total of 200 patients with E. faecium bloodstream infections (BSIs) were identified from the 4 participating centers, and 62 patients met the inclusion criteria. Depending on the site, the majority of patients were excluded because they were treated for fewer than 72 hours with daptomycin or with another therapy, clearance occurred prior to receipt of daptomycin, or there was a lack of follow-up culture (Figure 1). PFGE indicated that E. faecium isolates were not genetically related [25] (data not shown). Daptomycin MICs by Etest were equally distributed, with 31 patients exhibiting a daptomycin MICs of ≤2 µg/mL and 31 with MICs of 3–4 µg/mL. All daptomycin MICs by broth microdilution method were ≤2 µg/mL (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Methodology for application of exclusion criteria. Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; E. faecium, Enterococcus faecium.

The cohort of patients with E. faecium isolates with daptomycin MICs of 3–4 µg/mL were well matched to the cohort with MICs of ≤2 µg/mL in relation to all clinical data evaluated (Table 1). We found no statistically significant difference between the clinical characteristics of both cohorts when stratified by daptomycin MIC. Nonetheless, we observed several interesting trends that are important to highlight. There were more patients on hemodialysis in the group with daptomycin MICs 3–4 μg/mL vs ≤2 μg/mL (13 vs 7 patients; P = .10). The higher MIC group was more likely to have a catheter identified as a possible source of infection (18 vs 13 patients; P = .20) compared with the group with daptomycin MICs ≤ 2 µg/mL where an intraabdominal source of infection was more common (12 vs 9 patients; P = .42). Baseline comorbidities and Charlson scores were comparable. Finally, in terms of receipt of higher initial daptomycin dose (≥8 mg/kg), the 2 MIC groups were well matched (18 vs 17 patients; P = .80; Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics Stratified by Cohort Based on Daptomycin Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

| Characteristic | Enterococcus faecium MIC ≤ 2 µg/mL (n = 31) | Enterococcus faecium MIC 3–4 µg/mL (n = 31) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age ≥60 y | 18 (58.1) | 21 (67.7) | .43 |

| Male gender | 17 (54.8) | 16 (51.6) | .79 |

| Intensive care unit stay | 11 (35.5) | 14 (45.2) | .44 |

| Immunity and organ function | |||

| Immunosuppressive medication use | 10 (32.3) | 10 (32.3) | 1.00 |

| Any steroid use | 3 (9.7) | 6 (19.4) | .47 |

| Any transplant | 9 (29.0) | 8 (25.8) | .78 |

| Neutropenia | 13 (41.9) | 13 (41.9) | 1.00 |

| Recent chemotherapy | 11 (35.5) | 10 (32.3) | .79 |

| Acute kidney injury | 9 (29.0) | 13 (41.9) | .29 |

| Hemodialysis | 7 (22.6) | 13 (41.9) | .10 |

| Immunosuppressionb | 22 (71.0) | 26 (83.9) | .36 |

| Baseline comorbidities | |||

| Charlson score ≥4 | 12 (38.7) | 15 (48.4) | .44 |

| Any malignancy | 18 (58.1) | 19 (61.3) | .80 |

| Diabetes | 8 (25.8) | 11 (35.5) | .41 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8 (25.8) | 7 (22.6) | .77 |

| Coronary artery disease | 3 (9.7) | 8 (25.8) | .18 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | 1.00 |

| Dementia | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | .61 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 4 (12.9) | 5 (16.1) | 1.00 |

| Connective tissue disease | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| Ulcer disease | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 1.00 |

| Liver disease | 4 (12.9) | 5 (16.1) | 1.00 |

| Hemiplegia | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (19.4) | 12 (38.7) | .09 |

| Diabetes with end-organ damage | 2 (6.5) | 7 (22.6) | .15 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | .61 |

| Organism sensitivities and antibiotic history | |||

| Ampicillin resistance | 31 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | N/A |

| Linezolid resistance | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Vancomycin resistance | 29 (93.5) | 29 (93.5) | 1.00 |

| Aminoglycoside resistance | 7 (22.6) | 6 (19.4) | .76 |

| Prior daptomycin | 4 (12.9) | 6 (19.4) | .73 |

| Prior ampicillin | 2 (6.5) | 5 (16.1) | .42 |

| Prior vancomycin | 22 (71.0) | 23 (74.2) | .78 |

| Prior aminoglycoside | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | .35 |

| Initial daptomycin dose ≥8 mg/kg | 18 (58.1) | 17 (54.8) | .80 |

| Infectious sources | |||

| Endocarditis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| Catheter as potential sourcec | 13 (41.9) | 18 (58.1) | .20 |

| Abdomen as possible sourcec | 12 (38.7) | 9 (29.0) | .42 |

Data are presented as number (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; N/A, not applicable.

a P values based on χ2 or Fisher exact test where appropriate.

b Immunosuppression refers to composite of transplant, neutropenia, immunosuppressive medication use, any steroids, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus.

c When the source of infection was documented as deriving from a catheter or the abdomen by the primary treating physician.

By univariate analysis, we found that patients with BSI caused by E. faecium exhibiting an initial daptomycin MIC of 3–4 μg/mL had a higher rate of microbiologic failure compared with isolates with MICs < 2 µg/mL (P = .011). Neutropenia (P = .053) and presence of underlying malignancy (P = .054) were also closely associated with microbiologic failure. A composite variable for immunosuppression (including neutropenia and malignancy, steroid use, use of an immunosuppressive medication, and transplant) was significantly associated with microbiologic failure (P = .004). Daptomycin MIC of the initial isolate was not significantly associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality (P = .196). Clinical factors that correlated with all-cause in-hospital mortality were intensive care unit stay (P = .039), acute kidney injury (P = .006), and an abdominal source of infection (P = .013) (Table 2). Interestingly, initial daptomycin dose (stratified by dose ≥8 mg/kg vs lower doses) was not significantly associated with microbiologic failure or with in-hospital mortality. Similarly, we found no statistically significant relationship on univariate analysis between concomitant β-lactam antibiotic administration and microbiologic failure or mortality (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient Factors Significantly Associated With Microbiologic Failure and Associated Logistic Regression Model

| Factor | Clearance <4 d (n = 28) |

Clearance ≥4 d (n = 34) |

P Valuea | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium MIC 3–4 µg/mL | 9 | 32.1% | 22 | 64.7% | .011 | 4.701 | 1.371 | 16.118 | .014b |

| E. faecium MIC ≤ 2 µg/mL | 19 | 67.8% | 12 | 35.3% | .011 | ||||

| Immunosuppressionc | 17 | 60.7% | 31 | 91.2% | .004 | 5.318 | 1.201 | 23.54 | .028b |

| Charlson score ≥4 | 16 | 57.1% | 11 | 32.4% | .05 | 0.287 | 0.084 | 0.985 | .047b |

| Congestive heart failured | 11 | 39.3% | 4 | 11.8% | .017 | ||||

| Hemodialysisd | 13 | 46.4% | 7 | 20.6% | .03 | ||||

Data are presented as number, %, unless otherwise specified. Percentages were calculated with outcomes as denominator.

Abbreviation: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

a P values based on χ2, Fisher exact test, or analysis of variance where appropriate.

b Validated by bootstrap analysis.

c Immunosuppression refers to composite of any transplant, neutropenia, immunosuppressive medication use, any steroids, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus.

d Clinical factor not included in multivariate analysis due to low number of outcomes or as other clinical factors considered more cogent without overfitting model.

Logistic regression modeling of factors associated with microbiologic failure revealed that only daptomycin MIC 3–4 µg/mL (odds ratio [OR], 4.70 [1.37–16.12]; P = .014) and immunosuppression (OR, 5.318 [1.201–23.540]; P = .028) were significantly associated with this outcome. Interestingly, a Charlson score ≥4 was inversely correlated with microbiological failure (OR, 0.287 [0.084–0.985]; P = .047). Daptomycin MIC of 3–4 µg/mL and immunosuppression remained significantly associated with microbiologic failure after internal validation using bootstrap analysis (P = .010 and P = .017, respectively). The goodness-of-fit of the logistic model was verified using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (P = .659). Conversely, in the logistic regression model assessing in-hospital all-cause mortality using the 3 factors identified in the univariate analysis, none of the variables remained statistically significant (Table 3). Finally, given that only 2 patients experienced relapse under our definition, we did not pursue further analysis for this outcome.

Table 3.

Patient Factors Significantly Associated With In-Hospital All-Cause Mortality and Associated Logistic Regression Model

| Factor | Clearance <4 d (n = 28) |

Clearance ≥4 d (n = 34) |

P Valuea | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU stay | 11 | 29.7% | 14 | 56.0% | .039 | 1.818 | 0.549 | 6.02 | .328 |

| Acute kidney injury | 8 | 21.6% | 14 | 56.0% | .006 | 2.567 | 0.699 | 9.431 | .156 |

| Abdominal sourceb | 8 | 21.6% | 13 | 52.0% | .013 | 2.357 | 0.677 | 8.202 | .178 |

| ICU stayc | 11 | 29.70% | 14 | 56.00% | .039 | ||||

| Prior aminoglycosidec | 0 | 0.00% | 5 | 20.00% | .008 | ||||

Data are presented as number, %, unless otherwise specified. Percentages were calculated with outcomes as denominator.

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

a P values based on χ2, Fisher exact test, or analysis of variance where appropriate.

b When the source of infection was documented as deriving from the abdomen by the primary treating physician.

c Clinical factor not included in multivariate analysis due to low number of outcomes or as other clinical factors considered more cogent without overfitting model.

DISCUSSION

We and others have [16, 26] provided genetic, microbiological, and limited clinical data to suggest that E. faecium isolates with daptomycin MICs close to the breakpoint may not respond as well to this antibiotic even if higher doses are used. We now provide further clinical data that support our initial hypothesis. In this retrospective multicenter cohort study that spanned several years, we found a statistically significant decrease in microbiologic clearance in BSIs caused by E. faecium when the daptomycin MICs by Etest were 3–4 µg/mL (“susceptible” by current standards). This association remained significant when adjusted for immunosuppression and multiple comorbidities. Our results add strength to our previous observations and suggest that the current CLSI breakpoint for daptomycin in enterococci (4 µg/mL) should be reevaluated. Further support to our findings is provided by the concomitant determination of MICs using CLSI-recommended methodology (broth microdilution). Indeed, the daptomycin MICs of all isolates in our study were ≤2 µg/mL. This is consistent with our previous observations [16] that indicated that broth microdilution is not robust enough to identify subpopulations of resistant bacteria (similar to the phenomenon of vancomycin nonsusceptibility in S. aureus). As clinicians, we believe a breakpoint should be informative of patient outcomes regardless of the methodology used, and our findings suggest that Etest may be more predictive of patient outcomes when testing daptomycin. As such, an approach to serious infections caused by E. faecium should include the use of Etest (when possible), and MIC values of 3–4 µg/mL should be reclassified as “intermediate” or a note should be added to indicate that daptomycin monotherapy (even at higher doses) may not achieve microbiological clearance. Another finding in our study was that initial daptomycin dose was not significantly associated with either of the 2 primary outcomes evaluated and that the use of high-dose daptomycin in such situations may not be sufficient to overcome the “tolerance” mechanism. Although higher daptomycin doses are usually recommended to treat deep-seated enterococcal infections, it appears that once increases in the MIC occur (which correlate with specific mutations) [16], higher doses may not be beneficial. We also found no correlation between concomitant β-lactam use with microbiologic failure or clearance. Although the concomitant use of daptomycin plus β-lactams has been proposed to be synergistic against daptomycin nonsusceptible isolates [27–29], our study was not robust enough to evaluate therapeutic efficacy.

Of note, our study focused on microbiologic clearance as a principle endpoint. Prior studies of E. faecium BSIs primarily evaluated the effect of daptomycin treatment on all-cause mortality, which is likely due to the lack of availability of isolates and follow-up culture data. As E. faecium BSI often occurs in patients at high mortality risk (critically ill patients with multiple comorbidities), we believe microbiologic clearance represents a more “real” practice outcome that can affect decisions on duration of antimicrobial therapy. Additionally, our study stratified patients based on the MIC of the E. faecium isolated. In prior studies, stratification was based on choice of therapy [30], and daptomycin MIC values were often not made available, precluding the ability to obtain susceptibilities of the organisms. Therefore, these data were often not considered as a factor that contributed to outcomes.

Some limitations of our study include its retrospective nature and small sample size. There is intrinsic selection bias due to retrospective design and strict inclusion criteria. All collected data were extracted from existing databases, and that limited the study's scope. Of note, we found that most databases on daptomycin therapy related to E. faecium included numerous patients who had documented clearance even prior to receiving the first dose of daptomycin. We excluded these patients, and would recommend that future studies have a similar approach as E. faecium can colonize catheters. Further, catheter removal was not documented consistently among the databases, so we were not able to evaluate the effect of this intervention on the outcomes. These are potential confounders when evaluating therapeutic outcomes of invasive E. faecium infections. Additionally, the clinical response when antibiotics other than β-lactams were used simultaneously with daptomycin could not be assessed due to the limited availability of pharmacy records in the datasets. Lastly, we were not able to draw concrete correlations between individual comorbidities due to the small sample size. Our finding of an inverse relationship between Charlson score and microbiologic failure is intriguing but requires validation using more in-depth, prospective collection of comorbidity data. One possibility is that sicker patients are more likely to develop transient enterococcal bacteremia compared with healthier patients in whom infections may be more deep seated in nature. However, we were limited by the availability of data calculated by study members through chart abstraction. Indeed, data from patient charts is dependent on reliable physician documentation and may lead to underestimation of score. We believe this may be the case in our cohort since our data suggest that patients' comorbidities may not be highly correlated with microbiological clearance. Given the fact that the P value is close to the limit of statistical significance, a larger independent sample is needed to further attest or refute this finding. With the data available, we also created a separate model in which the Charlson score was replaced by its individual components. Interestingly, even in this model, the statistically significant variables (namely, congestive heart failure and hemodialysis) also exhibited inverse relationships. Finally, although the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score [31] is commonly used to stratify illness severity, we were not able to calculate these due to limited data available from the retrospective cohorts.

Similarly, the lack of mortality differences may be due to several factors. Indeed, E. faecium is not a highly virulent organism, and patients with bacteremia caused by this organism may remain bacteremic for prolonged periods. The attributable mortality of these bacteremic episodes is difficult to assess. Another explanation may be our definition of mortality. While we only assessed in-hospital mortality, it is possible that patients may have died after discharge.

We believe our study and its findings highlight the importance of the following 3 important elements that can inform future studies on enterococcal BSIs: robust clinical databases, interinstitutional collaboration, and availability of bacterial isolates. In future studies of serious bacterial illnesses, investigations should move past the reported antibiotic sensitivities and begin to incorporate genetic information that could guide the clinical decision-making process (akin to human immunodeficiency virus treatment). As our knowledge of the genetics of E. faecium expands, it will become even more prudent for these elements to be considered in clinical studies.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI093749 and R21 AI114961 to C. A. A. and R01 AI089891 to S. S.) and by the Chilean Ministry of Education, Clinical Alemana de Santiago, and Universidad del Desarrollo School of Medicine, Chile (to J. M. M.).

Potential conflicts of interest. J. A. has applied for grant funding from Merck & Co. C. A. A. has served as consultant to Pfizer Inc, Cubist Inc, Theravance, and Bayer and has received grant funding from Pfizer, Forest, and Theravance. M. J. Z. has received grants from Cubist, Pfizer, Tetraphase, Rempex, and Merck. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Hidron A, Edwards JR, Patel J et al. . NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29:996–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W et al. . Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clewell DB, Gawron-Burke C. Conjugative transposons and the dissemination of antibiotic resistance in streptococci. Annu Rev Microbiol 1986; 40:635–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells VD, Wong ES, Murray BE, Coudron PE, Williams DS, Markowitz SM. Infections due to beta-lactamase-producing, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116:285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zervos MJ, Kauffman CA, Therasse PM, Bergman AG, Mikesell TS, Schaberg DR. Nosocomial infection by gentamicin-resistant Streptococcus faecalis. An epidemiologic study. Ann Intern Med 1987; 106:687–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesho EP, Wortmann GW, Craft D, Moran KA. De novo daptomycin nonsusceptibility in a clinical isolate. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebreton F, van Schaik W, McGuire AM et al. . Emergence of epidemic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium from animal and commensal strains. MBio 2013; 4:pii:e00534–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiazGranados CA, Zimmer SM, Klein M, Jernigan JA. Comparison of mortality associated with vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible enterococcal bloodstream infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Smith P, Younger J, Lloyd-Smith E, Green H, Leung V, Romney MG. Economic analysis of vancomycin-resistant enterococci at a Canadian hospital: assessing attributable cost and length of stay. J Hosp Infect 2013; 85:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NDA 50-747/S-011, NDA 50-748/S-009 & S-010 Supplement Approval Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2010/050747s011,050748s009,050748s010ltr.pdf Accessed 2 July 2015.

- 11.Britt NS, Potter EM, Patel N, Steed ME. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of linezolid and daptomycin in vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bloodstream infection: a national cohort study of Veterans Affairs patients. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:871–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz-Price LS, Lolans K, Quinn JP. Emergence of resistance to daptomycin during treatment of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis infection. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:565–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis JS II, Owens A, Cadena J, Sabol K, Patterson JE, Jorgensen JH. Emergence of daptomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium during daptomycin therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:1664–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelesidis T, Humphries R, Uslan DZ, Pegues D. De novo daptomycin-nonsusceptible enterococcal infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:674–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz L, Tran TT, Munita JM et al. . Whole-genome analyses of Enterococcus faecium isolates with diverse daptomycin MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4527–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munita JM, Panesso D, Diaz L et al. . Correlation between mutations in liaFSR of Enterococcus faecium and MIC of daptomycin: revisiting daptomycin breakpoints. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:4354–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munita JM, Mishra NN, Alvarez D et al. . Failure of high-dose daptomycin for bacteremia caused by daptomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium harboring LiaSR substitutions. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1277–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crank CW, Scheetz MH, Brielmaier B et al. . Comparison of outcomes from daptomycin or linezolid treatment for vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bloodstream infection: a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study. Clin Ther 2010; 32:1713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mave V, Garcia-Diaz J, Islam T, Hasbun R. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteraemia: is daptomycin as effective as linezolid? J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 64:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987; 40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33:24–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 8th edition CLSI document M07-A8; Wayne, PA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 21st informational supplement. CLSI document MS100-S21; Wayne, PA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray BE, Singh KV, Heath JD, Sharma BR, Weinstock GM. Comparison of genomic DNAs of different enterococcal isolates using restriction endonucleases with infrequent recognition sites. J Clin Microbiol 1990; 28:2059–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV et al. . Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33:2233–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moise PA, Sakoulas G, McKinnell JA et al. . Clinical outcomes of daptomycin for vancomycin-resistant enterococcus bacteremia. Clin Ther 2015; 37:1443–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakoulas G, Bayer AS, Pogliano J et al. . Ampicillin enhances daptomycin- and cationic host defense peptide-mediated killing of ampicillin- and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:838–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sierra-Hoffman M, Iznaola O, Goodwin M, Mohr J. Combination therapy with ampicillin and daptomycin for treatment of Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakoulas G, Rose W, Nonejuie P et al. . Ceftaroline restores daptomycin activity against daptomycin-nonsusceptible vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:1494–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shukla BS, Gauthier TP, Correa R, Smith L, Abbo L. Treatment considerations in vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia: daptomycin or linezolid? A review. Int J Clin Pharm 2013; 35:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985; 13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.