Abstract

Background: Global health policy is created largely through a collaborative process between development agencies and aid-recipient governments, yet it remains unclear whether governments retain ownership over the creation of policy in their own countries. An assessment of the power structure in this relationship and its influence over agenda-setting is thus the first step towards understanding where progress is still needed in policy-making for development.

Methods: This study employed qualitative policy analysis methodology to examine how health-related policy agendas are adopted in low-income countries, using Tanzania as a case study. Semi-structured, in-depth, key informant interviews with 11 policy-makers were conducted on perspectives of the agenda-setting process and its actors. Kingdon’s stream theory was chosen as the lens through which to interpret the data analysis.

Results: This study demonstrates that while stakeholders each have ways of influencing the process, the power to do so can be assessed based on three major factors: financial incentives, technical expertise, and influential position. Since donors often have two or all of these elements simultaneously a natural power imbalance ensues, whereby donor interests tend to prevail over recipient government limitations in prioritization of agendas. One way to mediate these imbalances seems to be the initiation of meaningful policy dialogue.

Conclusion: In Tanzania, the agenda-setting process operates within a complex network of factors that interact until a "policy window" opens and a decision is made. Power in this process often lies not with the Tanzanian government but with the donors, and the contrast between latent presence and deliberate use of this power seems to be based on the donor ideology behind giving aid (defined here by funding modality). Donors who used pooled funding (PF) modalities were less likely to exploit their inherent power, whereas those who preferred to maintain maximum control over the aid they provided (ie, non-pooled funders) more readily wielded their intrinsic power to push their own priorities.

Keywords: Health Policy, Policy Analysis, Agenda-Setting, Power, Tanzania

Background

The national health policies of developing nations are shaped through the engagement of local governments by a global network of actors involved in development assistance. These actors include not only bilateral and multilateral donor agencies, but also organizations providing technical assistance and policy support as well as (more recently) on-the-ground implementing organizations, including civil society and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Historically, this transnational aid architecture has resulted in policy oversight by industrialized nations and multi-lateral institutions, who claimed a certain authority over the policy decisions made within developing health systems.1-6 More recently, however, the idea of “aid” has matured into the broader concept of “development cooperation,” placing larger emphasis on technical support and mutual accountability for development outcomes than traditional definitions of financial-only development assistance. Despite this shift, the exact influence of foreign stakeholders on national policies remains inconclusive, and further research into this area is essential for determining how donors and collaborators can best approach low-income countries.3,7

Numerous studies have described the economic and political factors involved in priority-setting8-10 and donor influence and coordination11-14 on policy-making in low-income countries. However, there remains a gap in understanding the provenance of power within the donor-recipient relationship, how it is employed by various actors, and whether there are factors that can increase transparency and accountability. Power can be understood in a multitude of ways. In many spheres (eg, political sociology, social psychology, international relations), the concept of power is typically thought of as the ability to influence others, or get someone to do something they would not otherwise do.15-19 While there are many other interpretations of the meaning of power, it was left undefined during the interviews and so the scope of this paper does not allow for a full examination of these alternative theories. As such, ‘power as influence’ will be taken as the operational definition of power for the purposes of this study, since this is the most common and likely how respondents conceptualized it during the interviews.

Given this definition, the present study seeks to evaluate how the power of both domestic stakeholders and foreign development agencies affects the national health policy agenda-setting process. The term ‘agenda-setting’ in this paper refers to the definition provided by Kingdon20 : “The list of subjects or problems to which government officials, and people outside of government closely associated with those officials, are paying some serious attention at any given time.” The example of the United Republic of Tanzania was used in this study to illustrate these dynamics.

Tanzania is well-positioned to provide insight into agenda-setting as a dynamic international process due to its dependence on donor aid.6,21,22 Still, the aid climate is fraught with competing interests as donors have tended to prefer disease-specific (or “vertical”) approaches, which are easier to track and control in terms of expenditure for output.23,24 Contributions made by donors often come attached to their priorities, so governments are not always able to allocate aid money to the priority areas of their choice. In fact, these conditions can create the perfect framework for fungibility–recipient governments allocating their own budget away from the programs being targeted by earmarked funding, thereby sustaining aid dependency.25-27 Yet accepting aid implies accepting input, so African governments have been subject to imposed conditions for assistance and inadequate governance and ownership over their own health programs and policies for decades,28-31 and despite advances in the realm of development cooperation the age-old problems of donor conditionality, competing interests, and vertical-only programs persist.28,29,32-35

In this context, little is known about power imbalance (real or perceived) so a candid analysis of stakeholder perspectives regarding aid effectiveness issues and their potential solutions is warranted. Furthermore, the formal, externally-facing process is somewhat superficial, as policy is often influenced through informal negotiation behind closed doors.3,35 The intention in this paper is, therefore, to provide an analysis of the power dynamics in the agenda-setting process of the Tanzanian health sector from the perspective of major stakeholders, both national and international. To do so, we have defined three specific objectives: (1) investigate how items make it onto the policy agenda; (2) determine who makes these decisions; and (3) elucidate whence the power to do so is derived. We hope to further unpack how power affects policy-making in aid-recipient countries and elucidate mechanisms for mediating these dynamics. This paper begins by examining the current health policy landscape in Tanzania and considering the interview data. From there, an analytical framework based on stakeholder perspectives of the policy process is presented, detailing the major recurrent themes found within the interviews. Finally, results are framed within Kingdon’s20 theory.

Methods

This study employed qualitative research methodology, including in-depth, semi-structured interviews with key informants in the health sector.36 A case study design was chosen in order to best examine stakeholder perspectives and uncover complex circumstantial nuances that are nearly impossible to investigate using other approaches.37

A combination of purposive expert sampling and chain-referral sampling techniques was used.38-40 Purposive sampling was favored here because it allowed access to a representative group of experts with diverse experience and perspectives. The target group of experts included officials who had direct access to and experience in the health policy-making process in Tanzania. The sampling inclusion criteria were purposefully broad, as they aimed to include domestic actors as well as bilateral and multilateral agencies and non-donor experts in the field. Any representatives from implementing organizations (eg, civil society, NGOs, etc.) were excluded from this study. While they do attend many of the health sector meetings and their influence is steadily increasing, their participation and impact is still too variable to measure effectively. In addition, because they are mainly involved in service delivery, their role in the agenda-setting process is less involved.

All interviews were conducted during the spring of 2011. Stakeholders who agreed to participate after initial contact were interviewed. A chain-referral sampling technique was then used, requesting informants to identify other potential participants by naming colleagues or collaborators who were also involved in the health policy-making process. Through this method, several individuals were accessed with whom the chance of an interview would have otherwise been low. In total, eleven people participated, ranging from a variety of affiliations throughout the health sector. Three participants came from within the Ministry of Health (MoH), five were Development Partners (three bilateral and two multilateral) and three were non-participating experts on the process, of which one was a local doctor and advocate, one an international health donor/ consultant (characterized as a donor in analyses), and one a policy researcher. Due to the nature of policy work, few people have deep insight into the inner workings of the policy-making process, making it difficult to recruit a large sample. Thus, despite the relatively small number of participants there was sufficient breadth and diversity to offer a high degree of confidence in the sample.

Data Collection

Interviews followed the guide to conducting key informant interviews proposed by USAID41 since this document is recognized as a standard reference in the field. Most interviews were given in person or over the phone, though two interviews were completed via email due to time constraint of the participant. For the two respondents who were interviewed via email, we sent a document with all of the major guiding questions. Based on the depth of received responses, we followed up with further probing or clarifying questions. While email is not an ideal medium for conducting interviews, we feel that additional insight on the policy-making process was nevertheless gleaned and that these interview data added value to the study.

Questions for the interview guide were developed based on a model proposed by Maykut and Morehouse,42 in which a systematic procedure is followed to ensure proper structure and breadth. Exact queries during in-person/phone interviews were adapted to follow the ad hoc flow of conversation and to best fit the informant’s area of expertise within the sector. Guiding questions for all participants involved the person’s/organization’s role within the health policy process, their perception of priorities in health policy and programs, their opinion on why certain programs are brought to the table while others are left out, their thoughts on the interaction between the government and development partners, who they believe has the most power and influence in the agenda-setting process, and what gives them that power.

Data Analysis

Interview data were examined using a thematic analysis approach to qualitative research,43,44 whereby rigorous, systematic coding and categorization of major themes was conducted on the interview transcripts and notes. First, words or phrases were extracted from the transcripts and coded by topic. Some topics included ‘money,’ ‘priorities,’ ‘evidence,’ ‘expertise,’ and ‘dialogue.’ Once codes were assigned, they were categorized into broader themes according to frequency; the three final emergent themes were “idea development,” “prioritization,” and “power.” Sub-themes also emerged within each category and further described the findings within each major theme.

Throughout analysis, it was noted which of the sub-themes were mentioned by participants during discussion of each major theme. These were ranked chronologically; it was assumed that a participant’s initial response was the first ranked (ie, most important) and anything mentioned afterwards was given second, then third rank. This establishes which sub-themes were discussed most prominently during interviews and, therefore, which responses may be considered most important to the agenda-setting process in Tanzania.

Theoretical Framework

This study utilizes Kingdon’s20 stream theory to frame the empirical results in a theoretical context. Stream theory asserts that policy can only be made when three streams – problem, politics and policy – converge to form “policy windows.” This model recognizes agenda-setting as a highly complex process, requiring substantive evidence, support, timing and political will in order for an issue to be recognized as ‘important enough’ to be on the agenda.

The problem stream consists of how certain conditions become recognized as problems whose solutions take priority on the agenda. Indicators are often used to keep track of problems and their changes in pattern and magnitude. Many things can move a problem up the agenda, including epidemics, personal experiences of policy-makers, feedback from existing programs or policies, and budget considerations.20 The problem stream will be used in this analysis to frame the question of how an idea gets taken from a stakeholder and put onto the policy agenda (Objective 1).

The policy stream deals with the birth and growth of policy proposals. For a proposal to survive, it must fulfill certain criteria, such as technical feasibility, public acceptance and reasonable cost. These proposals need to find a problem to become attached to and a certain amount of backing in order to take priority on the agenda.20 The policy stream will be used in this analysis to frame the question of how policies ‘find’ a problem to back up and who is behind those policies (Objective 2).

The political stream deals with things such as national mood, consensus among organized forces and changes in government. In other words, the political mood must be right in order for an item to take precedence on the agenda.20 The political stream will be used in this analysis to frame the question of how politics, both domestic and foreign, influence the agenda and allow certain items to move to the top of the list. It will also help us to understand who has the power to influence the decision-making process (Objective 3).

Results

Current Health Policy Structure and Funding Mechanisms in Tanzania

The Government of Tanzania (GoT) is divided into Ministries, including the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW), which is responsible in part for devising the Health Sector Strategic Plan (at the time of the study, version HSSP III, July 2009-June 2015).45 The major stakeholders involved in deciding the content of these policies are the MoHSW and the Development Partners Group for Health (DPG), which consists of 17 bilateral and multilateral agencies. Official policies are finalized at the Joint Annual Health Sector Review, where progress toward HSSP milestones is addressed. Alongside this process, informal technical support is acquired through day-to-day interactions between donors, government officials, and implementing organizations.

Financial assistance from the DPG comes in two forms: pooled and non-pooled. Pooled funding (PF) includes general budget support (GBS) and health basket funds (HBF). With GBS, donors place a bulk sum into the national budget to be allocated to programs at the discretion of domestic policy-makers. HBF are structured such that donors pool resources for a specific sector, in this case health, to be allocated to shared priorities within that sector. These PF mechanisms are meant to provide aid recipients with greater authority over their domestic budgets, assuming that they understand best where funding will have greatest impact.46

Non-pooled (ie, earmarked) funding (NPF), on the other hand, is a more donor-friendly funding modality. Most donors, including those who give primarily to the HBF, have non-pooled money set apart for funding specific vertical programs.47 This approach allows the least ownership to governments and the least alignment between donors and recipients.48 Nevertheless, it is also the easiest method for filling in gaps left by pooled or on-budget funding and, therefore, remains popular with donors.

Idea Development

Across policy theory and the policy cycle framework,49 issue identification is regarded as the ‘first step’ towards the creation of health policy, so all interviews began with the question, “In your opinion, how does an idea become recognized and put onto the policy agenda?” Three prominent responses to this question were found. These responses were split evenly across all interviewees, and no particular response trend was noted when accounting for organizational affiliation (Table).

Table. Ranking of Responsesa .

| Idea Development | Power | |||||||

| Problem | Evidence | People | Combo | Position | Expertise | Money | Combo | |

| MoHSW 1 | - | 1 | 2 | X | 2 | - | 1 | X |

| MoHSW 2 | 1 | - | 2 | X | 1 | - | 2 | X |

| MoHSW 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | X | - | 1 | 2 | X |

| PF donor 1 | 2 | - | 1 | X | 3 | 2 | 1 | X |

| PF donor 2 | 1 | - | 2 | X | 2 | 3 | 1 | X |

| PF donor 3 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | X |

| PF donor 4 | - | - | 1 | X | 1 | - | 2 | X |

| NPF donor 1 | - | 2 | 1 | X | - | 1 | 2 | X |

| NPF donor 2 | - | 1 | 2 | X | - | 2 | 1 | X |

| Expert 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 1 | - |

| Expert 2 | 1 | - | 2 | X | - | 1 | - | X |

| Total rank 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | - | 3 | 3 | 5 | - |

| Totals | 14 | 10 | 26 | 9/11 | 14 | 16 | 23 | 10/11 |

Abbreviations: MoHSW, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; PF, pooled funding; NPF, non-pooled funding; Combo: X indicates that a respondent recognized a combination of factors that influence Idea Development or Power.

aNumbers represent rank, whereby 1 is primary response, and 2 and 3 (where relevant) are secondary and tertiary response, respectively. In terms of primary ranking, People and Money had the most votes. A dash means that topic was not prominently discussed during the interview. The ‘Totals’ row is counted backwards, with first rank getting 3 points, second rank getting 2 points and third rank getting 1 point. This shows relative weighting of importance within each category and more starkly identifies People (in Idea Development) and Money (in Power) as “winners” of their respective categories.

Essentially, (1) either an issue perceived as a problem is floated, (2) a person finds some value (whether monetary or ideological) in an idea, or (3) there is incontrovertible evidence that a problem requires addressing. Nevertheless, it was recognized by all participants that the mechanism behind the development of an agenda item is often the combination of these factors.

“…it isn’t a uni-dimensional thing where you say ‘ah ha!’ This is the key! This is the button that you need to push in order to make something happen” (Health Development Partner).

For example, problems are always pervasive, but they alone cannot create more than the idea for a policy. Likewise, evidence bolsters policy ideas but itself cannot push them onto the agenda. In order to transform that idea into policy, there needs to be a certain level of buy-in.20

“I think a person or set of individuals or organizations who are determined can use that evidence and data to get [the idea] onto a policy agenda … and I guess at some stage … a critical mass of other organizations or influential players buy into the issue at stake and recognize its importance and need to be on the policy agenda” (External Stakeholder).

A person or organization with influential position seems to have the greatest possibility of moving problems to the forefront of the agenda and everyone interviewed agreed that no matter whence an idea derives, it takes someone’s backing to move it forward.

Prioritization

Formally, the HSSP III contains the priority strategies of the MoHSW.45 However, several respondents admitted that policy issues do not necessarily bear any relation to actual needs on the ground. Fundamentally, priorities made at the central level often ignore local issues.49 In fact, global priorities such as the MDGs often take precedence even over national determination or need.50 For example, some respondents argued that communicable disease programs were highest on the agenda but that other issues (eg, health systems strengthening) should be of higher priority. Further, it was impossible to ignore the funding imperative that so often drives these trends.

“Sometimes things get funded because they become a high enough priority. Some things, they become a high priority because of funding” (Health Development Partner).

As this quote reflects, some items are prioritized due to funding alone; for example, a donor may approach a country with $1 million to allocate to HIV/AIDS programs, regardless of whether the country feels this is the most efficient use of those resources. Several respondents mentioned that donors tend to look at the macro picture, investing mainly in areas where there will be directly observable output. This finding has also been shown in previous research and agrees with the respondents’ perspective.51 With vertical programs, impact per dollar is easy to trace whereas through the funding modalities of GBS or HBF, it is significantly more difficult to know what effect additional funding actually has on health outcomes.46 Furthermore, donors are beholden to their own governments. In this way, the intrinsic interests of the donor country (eg, national security, tax benefit, domestically-made products, etc.) can trump true needs on the ground.3 Thus, through funding mechanism and political support, donors can influence agendas and quite forcefully bring their own priorities to the table.

Conversely, without funding it is impossible for governments to implement programs or operationalize policy strategies. Often the incentive driving policy change is financial and it would be easier for governments to simply concede to donor priorities rather than risk losing a substantial investment, as demonstrated below.

“You will want to change a policy but you don’t have funds. What do you do? Somebody who has funds, he has got his or her own priorities. So you have to welcome him or her so that you just get that money and then within that money you also make a spillover to your priorities which you have” (Official, MoH).

This quote also demonstrates nicely the principle of fungibility as a drawback to donor-driven development. Waddington52 argues this nicely: “A government that responds to earmarked donor funds by moving its own money away from that activity is often behaving rationally and responsibly: it is avoiding duplication and putting the freed-up resources to another use. The risk is that these new funding patterns become established, and that they reduce the likelihood that funding for the externally supported activity will continue beyond the period of donor earmarking.” This fungibility perpetuates aid dependency and detracts from the overall efficiency of donor funding.

Policy Dialogue for Mediating Prioritization

It is clear that donors influence governmental priorities through the money they provide, and financial restraints obviously play a huge role in the negotiating power of governments to defend their priorities, especially with earmarked funding.

“I think [governments] can negotiate, but as a government they have to make a decision; that if they are lacking in resources and the amount of money that is on the table is quite significant, and if that is the difference between being able to put $12 per person into a health system instead of $10 per person into a health system then it’s hard for a responsible minister in charge of the health of the country to say no” (External Stakeholder).

When funding enters the country as off-budget project support, it is not necessarily designated to the priorities of the Ministry,53,54 so negotiation is more difficult when there is contention between priorities.10,50

“…to have policy discussions with someone who is just sitting there with a lot of money behind him or her and then having funny ideas about running the sector, it’s not really something which creates the right atmosphere for productive collaboration and policy dialogue” (Official, MoH).

With the PF modalities of GBS and HBF on the other hand, the intention is for donors to adopt and support the priorities set out by the government so they may not feel comfortable arguing a point if they disagree with the MoHSW.55

“…the general budget support and basket funding are just… people will not have that hard discussion, people will not cut the Ministry off, it’s taken 10 years and people are finally just throwing their hands in the air rather than having that technical discussion about what worked and didn’t work” (Health Development Partner).

Policy dialogue, when done correctly, can be a boon to stakeholders when there is contention between priorities. However, this is an intricate dance and requires patience and compromise to be most effective in mediating priorities.

Power

The true challenge in policy-making is indeed that power can manifest itself in various ways and it is difficult to reconcile these into a coherent policy-making strategy.17,56 This heterogeneity is demonstrated in the responses on power given by our interviewees (Table ). Several respondents believed that the key power base behind decisions made in the country comes from within the MoHSW. Others argued that while the ultimate decision does indeed lie within the jurisdiction of the Ministry, the major source of power stemmed from technical expertise and evidence. The third and largest group asserted that money is the main source of power in decision-making.

Of those who contended that the main source of power comes from within the Ministry, only one was a MoHSW official, while the other two were development partners. Both of the development partners in this group most heavily supported PF mechanisms, demonstrating that PF leads to greater ownership for governments. Naturally, no policy decision can be made in Tanzania without the signature of the Minister of Health, obliging the MoHSW, at least formally, with decision-making power. Nevertheless, other stakeholders (namely donors) can influence these decisions by pushing the MoHSW to consider other options.

The second largest group considered technical expertise the greatest source of power. This group consisted of one NPF donor, one Ministry official and one outside expert. The donor argued that while the ultimate decision whether to sign lies with the Ministry, donors or other actors can come together, “with conclusive data and a body of international experience… and so a concerted effort by a number of partners will tend to cave in what is considered ill-conceived opposition.” For example, one respondent told a story about a development agency that managed to force through a specific brand of birth control because they not only had the money behind them, but also good evidence that theirs was the best for the situation. Hence, a strong argument with robust evidence-based rationale can sway opposing stakeholders and their interests. Likewise, if there is a disagreement, backing an idea with incontrovertible data can help ‘win over’ your opponents.57,58

The third major source of decision-making power was financial. The group that upheld this argument extended across participants, regardless of affiliation. Only two respondents (one PF bilateral donor and one external stakeholder) denied that money has any sort of substantial impact on power. All other respondents, even if it was not their chief argument, recognized that money has at least some influence in the policy-making process. For example, after discussing technical expertise as the main source of power with one respondent, the following conversation ensued:

“Investigator: Then how much [power] would you say is attributed to money?

Respondent: A great deal.

Investigator: So if you have both, you pretty much win?

Respondent: Yes” (Health Development Partner).

Money can create a natural power imbalance between stakeholders, allowing donor interests to prevail over those of the recipient as a result of financial limitations.24,54 As many respondents cited, this is what happened with large Global Health Initiatives such as the Global Fund and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) with respect to HIV and other communicable disease programs. Due to the money allocated through these channels, vertical programs have had a great deal of leverage on the agenda.50 Fungibility is also strongest with project funding, as demonstrated here:

“…we cannot blame the government, I mean, they have so many other needs that whenever there’s funding for something, you would be stupid to invest your own money when others are ready to fund” (Health Development Partner).

In this way, money can be an enormous factor in determining which items make it to the top of the agenda and how the decision to fund various programs and services is made.

Discussion

Analytical Framework

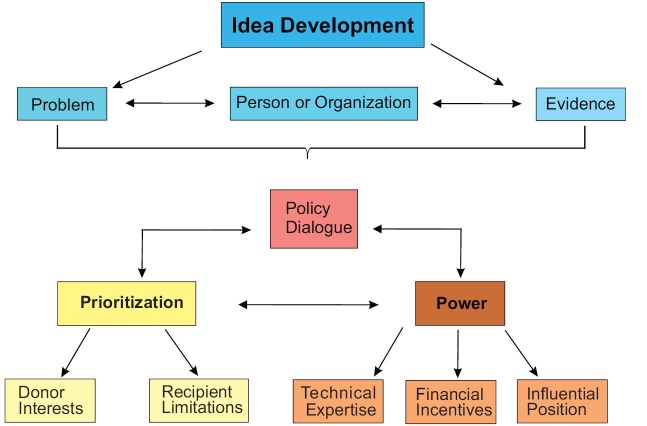

The analytical framework (Figure) was developed based on transcript analyses to characterize the key messages found across the interviews. These were placed into a ‘map’ of interrelationships to provide a visualization of the data. It is obvious here that the major stakeholders in the process are those with money, position, or expertise, though these characteristics overlap in many actors. In terms of prioritization, donor interests and recipient governments’ limitations appear to be in opposition, though this can by mediated through policy dialogue, which arguably engenders greater harmonization in agenda-setting.

Figure.

Analytical Framework.

Analytical Framework: Definitions

Idea Development: How an idea is recognized and put onto the policy agenda. Problem: An item that has been flagged as worth considering, through media, a landmark event, etc. Evidence: Undeniable proof of a trend, through research findings or health indicators. Person or Organization: Someone who has substantial influence (eg, Minister of Health, representative of a large donor organization, etc). Prioritization: Which items are considered of highest importance on the agenda. Donor Interests: Items on the agenda that have a particular pull for donors. Recipient Limitations: Restrictions of recipient governments due to lack of funds/expertise. Policy Dialogue: Discourse between recipient, donor, and third party (where relevant) with the intent of harmonizing agenda items. Power: Influence of a stakeholder in determining agenda items or swaying popular opinion. Influential Position: Status or title that gives natural authority over decision-making. Technical Expertise: Ability to supply evidence to support an argument due to topical knowledge. Financial Incentives: Financial backing of an idea or agenda item.

Kingdon’s Stream Theory

Links between data analysis and policy theory were made only after full independent categorization of the data. The theoretical context can help clarify how certain programs and services are prioritized and who has the power to push these items through.

Idea Development and Stream Theory

In relationship to the analytical framework, Kingdon’s20 problem stream matches most closely to Idea Development. The problem stream determines how certain conditions can be met in order for an item to necessitate space on the policy agenda. Various channels (notably problems, evidence, and people/organizations) may be used to push something forward, but no single factor is sufficient in itself to ensure that an idea will be put on the agenda.

Prioritization and Stream Theory

Prioritization can be viewed through the lens of Kingdon’s20 policy stream. Policies that are brought to the table by both donors and recipients can shape the agenda, and the dialogue that occurs between these actors in order to support one policy over another is a major factor in whether an item reaches the agenda. This stream also encompasses the way certain policies “find” a problem to back up and who is behind those policies. Kingdon mentions the necessity of having ‘advocates’ for a policy, and this was seen throughout the interviews as respondents noted that without the substantial backing of certain parties and the policy dialogue that flows between them, agenda items are more likely to get lost amongst the numerous ideas that are constantly being floated for discussion.

Power and Stream Theory

Power can be viewed through Kingdon’s20 political stream. While it is not possible to conclusively declare what gives the power to set agendas or make decisions, it can be stated that it almost always takes a combination of factors (whether money, expertise, or influential position) to employ that power. In addition, it is clear that politics – both domestic and international – can heavily influence the trends of health policy in developing countries50 by using the influence of globally recognized positions of authority, ability to mobilize resources, and capacity to support claims with strong evidence to influence policy.

Conclusion

This paper sought to identify stakeholder perspectives on the power dynamics of health policy agenda-setting in Tanzania. The analytical map, which helps to visualize the interview data, complements Kingdon’s20 theory, which provides a framework through which we can view the process and its major influences. Kingdon’s theory was built on the understanding of policy-making in the United States, and while many of his concepts are relevant to international policy there are factors in aid-recipient countries (eg, the donor-recipient relationship itself) that are not so easily explained by his theory. To complement the multiple streams, one can envision the forces of financial incentives, technical expertise, and influential position acting as agents that redirect the streams towards or away from the others, and, therefore, the final ‘policy window.’ In this way, we can begin to more fully understand – both theoretically and practically – the components of agenda-setting and use this knowledge to inform coordination efforts in aid-recipient countries.

When asked how an item makes it onto the policy agenda (Objective 1), most respondents agreed that a person or people needed to back an idea. The ability to combine this support with evidence made success more likely. The route to the agenda, however, was not so clear cut, and the priorities of policy-makers differ depending on affiliation. Various factors could shape these priorities, including emergent or existing problems, personal stake, political interests, or financial incentives, so there is often not consensus in the agenda-setting process.

One major consideration in the policy-making process is who has the ability to make policy decisions (Objective 2). As demonstrated in the results, funding can be redirected as circumstances so demand, as is often the case with donor earmarks for NPF. Although the Sector-Wide Approach has demonstrated some clear benefits in the objectives of ownership and alignment, donor-driven policy in Tanzania is still overwhelmingly present.13,59 This idea is supported by a broad base of literature stating that significant aid flows from donor organizations largely influence the national strategies of recipient countries.2,3,10,11,32,35,49,50 This does not necessarily mean that donors always have the largest say, or that they are the ones who make the final decisions, but there is clearly an imbalanced interplay between donor and recipient. Ownership of development priorities is, therefore, muddled and negotiations can often be laden with unhelpful backchannel arguments, leading to an increase in fungibility when donors get their way.

The power to make decisions (Objective 3) derives largely from one of three factors: financial backing, technical expertise, or influential position. One interesting finding was that PF and NPF donors responded differently on questions regarding power, as seen in Table. Both of the PF donors who mentioned influential position as the greatest source of power specifically defined this as the MoHSW during interviews, demonstrating that these donors concede their power to support the priorities of the recipient government. One of these even vehemently stated that money has no bearing on policy discussions between donor and recipient. This would lead to the conclusion that the ideology surrounding PF modalities (ie, ownership and alignment) restrains certain donors from using their inherent power to push their own agendas.

A second point of interest on this topic is that having the greatest amount of power in the agenda-setting process is increased by the ability to somehow combine influential position and technical expertise if you are not the one with the money. This finding has strong policy implications, arguing that greater emphasis on domestic-based research and evaluation of health indicators, service delivery and current policy strategies is essential. In this way, recipient governments would be encouraged to use their own data-based evidence, leveling the playing field by bringing domestic technical expertise to the table.

One missing link in this story might well be the effective implementation of policy dialogue. It is quite obvious that communication and compromise will enhance the effectiveness of aid and development cooperation overall, yet the ability to do so is hampered by power imbalance and varying degrees of consensus regarding priorities.50,60 Adhering to the ideal of national ownership should not mean that donors are discouraged from expressing their opinions over policies if they disagree. Likewise, approaching a country with earmarked funding should not equate to donor interests steamrolling those of the recipient. As explained through Kingdon,20 agendas are not set arbitrarily. It takes a perfect storm of political will, policy support and the evidence of a problem for issues to reach an agenda. Policy dialogue should be used to mediate these conflicting ideas and data-based decision-making should trump many of the other factors.

Limitations of this paper include sampling issues and overall generalizability. The sample size was limited, though as previously expressed it was felt that there was sufficient breadth to not substantially skew the results. Likewise, the sampling technique created a natural limitation in who participated, though this paper does not claim to have taken into account the influence of every stakeholder. Second, this study was conducted on the policy-making process in Tanzania only, affecting the possibility to confidently generalize to other low-income countries. However, it would be interesting to examine whether the results found in this study would be reproducible, and similar research should be applied within and between other aid-recipient countries to analyze which mechanisms most contribute to successful health outcomes, reduce aid dependency, and fully promote ownership and sustainability. This would also allow development partners to better coordinate aid, plan programs, and reform health systems to embolden mutually-agreed, evidence-based priorities.

Aid-recipient governments certainly do not have all the knowledge necessary to fix their health systems, and donors undoubtedly have a wealth of valuable input to provide. The key for progressing in effective policy-making is to foster working relationships that facilitate and emphasize meaningful policy dialogue, with the aim of setting agendas in consensus, utilizing the best available evidentiary support, and understanding fully how power dynamics affect not only the process, but also the outcomes, of national health policies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Danida Fellowship Centre of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Copenhagen, Denmark. We would also like to acknowledge significant contributions from Graham Jones of the University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK for his oversight and mentorship, Emmanuel Kwilasa of the Humanity Assistance Centre, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania for his help in the field and obtaining the research permit, and Amy Barnes of the University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK for her contribution to editing and peer review.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval was obtained from the necessary institutions (University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK and National Institute of Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania). Recruitment was strictly voluntary and informed consent was obtained from each participant at the time of the interview. Voice recording was conducted only when participants agreed to it (seven out of nine respondents). All participants had the choice to not have quotations used in the final paper and those that were used were sent to participants for approval prior to being added. (Note: No ethical review board existed at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark at the time of the study).

Competing interests

No disclosures to report for Sara Elisa Fischer. Martin Strandberg-Larsen is an employee at H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark and a shareholder in Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd, Denmark.

Authors’ contributions

SEF and MSL contributed to the conception and design of the study. SEF carried out all of the ethics review procedures, data collection, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. MSL assisted in the interpretation of the data analysis. Both authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and revisions of the manuscript.

Authors’ Affiliations

1Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. 2School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. 3Centre for Health Economics and Policy (CHEP), University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

Power is a complex notion involving political forces that should not be overlooked in international policy-making; on the contrary, power should be analyzed and carefully considered throughout the process.

Donors who wish to negotiate with low-income country governments on the aid they provide should keep in mind that simply being ‘the donor’ provides them with an inherent power advantage over recipient governments.

Low-income country governments should recognize and capitalize on their ability to negotiate for their own priorities, regardless of donor funding modality.

Of the three major sources of power in policy-making, technical expertise is the simplest to improve in low-income countries. As such, governments should encourage evidence-based decision-making and emphasize the need for strong national research programs.

Aid is intrinsically fungible so policy-makers should work together to identify solutions that maximize the effectiveness of additional financial flows to the health sector.

Implications for public

Policy-making in low-income countries is affected a great deal by international socio-political forces. It is important to keep in mind that throughout the process of policy creation, power is wielded in various ways in order to push certain agendas. This power is inherently understood, but not always widely discussed. A greater understanding of the use (or abuse) of power in policy-making is important in order to ensure that aid is as effective as possible and that low-income countries (and their poverty-stricken beneficiaries) are reaping the maximum possible benefit from these transactions. By understanding the way in which power operates, we are better able to enforce accountability for the decisions made by our governing bodies.

Citation: Fischer SE, Strandberg-Larsen M. Power and agenda-setting in Tanzanian health policy: an analysis of stakeholder perspectives. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(6):355–363. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.09

References

- 1.Yach D, Bettcher D. The globalization of public health, I: Threats and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(5):735–738. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ollila E. Global health priorities - priorities of the wealthy? Global Health. 2005;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Groves LC, Hinton RB. Inclusive Aid: Changing Power and Relationships in International Development. London ; Sterling, Va: Earthscan; 2004.

- 4. Clapham C. Africa and the International System: the Politics of State Survival: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

- 5.Hafner T, Shiffman J. The emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(1):41–50. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. United Nations (UN). Economic Development in Africa: Doubling Aid: Making the “Big Push” Work. New York: UN; 2006.

- 7.Gilson L, Raphaely N. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 1994-2007. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):294–307. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitton C, Donaldson C. Health care priority setting: principles, practice and challenges. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2004;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colenbrander S, Birungi C, Mbonye AK. Consensus and contention in the priority setting process: examining the health sector in Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(5):555–565. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenniskens F, Tiendrebeogo G, Coolen A. et al. How countries cope with competing demands and expectations: perspectives of different stakeholders on priority setting and resource allocation for health in the era of HIV and AIDS. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1071. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koduah A, van Dijk H, Agyepong IA. The role of policy actors and contextual factors in policy agenda setting and formulation: maternal fee exemption policies in Ghana over four and a half decades. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:27. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okuonzi SA, Macrae J. Whose policy is it anyway? International and national influences on health policy development in Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 1995;10(2):122–132. doi: 10.1093/heapol/10.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walt G, Pavignani E, Gilson L, Buse K. Managing external resources in the health sector: are there lessons for SWAps (sector-wide approaches)? Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(3):273–284. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buse K. Keeping a tight grip on the reins: donor control over aid coordination and management in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(3):219–228. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making Health Policy. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005.

- 16. Dahl R. Who Governs? Democracy and power in an American City. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1961.

- 17.Shiffman J. Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(6):297–299. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skvoretz J, Willer D. Exclusion and Power: A Test of Four Theories of Power in Exchange Networks. Am Sociol Rev. 1993;58(6):801–818. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner JC. Explaining the nature of power: A three-process theory. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2005;35(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. 2nd ed. New York: Addison-Wesley Longman; 1995.

- 21.Enserink M. After the windfall. Science. 2014;345(6202):1258–1259. doi: 10.1126/science.345.6202.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. OECD. DAC Peer Review: Tanzania. Paris, France: OECD; 2003.

- 23. Atun R, Bennett S, Duran A. When do vertical (stand-alone) programmes have a place in health systems? Tallinn, Estonia: World Health Organization; 2008.

- 24. Dodd R, Schieber G, Cassels A, Fleisher L, Gottret P. Working Paper 9: Aid Effectiveness and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

- 25. Beynon J. Policy Implications for Aid Allocations of Recent Research on Aid Effectiveness and Selectivity: A Summary. Paris: OECD; 2001.

- 26. Devarajan S, Swaroop V. The implications of foreign aid fungibility for development assistance: Policy Research Working Paper 2022. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1998.

- 27.Lu C, Schneider MT, Gubbins P, Leach-Kemon K, Jamison D, Murray CJ. Public financing of health in developing countries: a cross-national systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1375–1387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mbacke CS. African leadership for sustainable health policy and systems research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-S2-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stierman E, Ssengooba F, Bennett S. Aid alignment: a longer term lens on trends in development assistance for health in Uganda. Global Health. 2013;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brautigam DA, Knack S. Foreign aid, institutions, and governance in sub-Saharan Africa. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2004;52(2):255–285. doi: 10.1086/380592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dieleman JL, Graves CM, Templin T. et al. Global health development assistance remained steady in 2013 but did not align with recipients’ disease burden. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(5):878–886. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCoy D, Chand S, Sridhar D. Global health funding: how much, where it comes from and where it goes. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(6):407–417. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundewall J, Jonsson K, Cheelo C, Tomson G. Stakeholder perceptions of aid coordination implementation in the Zambian health sector. Health Policy. 2010;95(2-3):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyden G. After the paris declaration: Taking on the issue of power. Dev Policy Rev. 2008;26(3):259–274. doi: 10.1111/J.1467-7679.2008.00410.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hyden G, Mmuya M. Power and Policy Slippage in Tanzania - Discussing National Ownership of Development. Sweden: Sida; 2008.

- 36.Varvasovszky Z, Brugha R. A stakeholder analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15(3):338–345. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Feagin JR, Orum AM, Sjoberg G. A Case for the Case Study. UNC Press; 1991.

- 38.Luborsky MR, Rubinstein RL. Sampling in qualitative research: rationale, issues, and methods. Res Aging. 1995;17(1):89–113. doi: 10.1177/0164027595171005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bryman A. Social Research Methods. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- 40.Biernacki P, Waldorf D. Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol Methods Res. 1981;10(2):141–163. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumar K. Conducting Key Informant Interviews in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: USAID; 1989.

- 42. Maykut P, Morehouse R. Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide: Falmer Press; 1994.

- 43. Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2012.

- 44.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Government of Tanzania (GoT). Health Sector Strategic Plan III (July 2009 - June 2015): Partnership for Delivering the MDGs. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, United Republic of Tanzania; 2009.

- 46. Overseas Development Institute (ODI). Common funds for sector support: Building blocks or stumbling blocks? London: ODI; 2008.

- 47. Government of Tanzania (GoT). Aid Management Platform: Analysis of ODA Portfolio for FY 2010/11 & 2011/12. Dar es Salaa, Tanzania: Ministry of Finance, United Republic of Tanzania; 2013.

- 48. World Bank. Joint Assistance Strategy for the United Republic of Tanzania: FY2007 - FY2010. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: United Republic of Tanzania, Tanzania Development Partners Group and World Bank Group; 2007.

- 49. Walt G. Health Policy: An Introduction to Process and Power. Zed Books; 1994.

- 50.Perin I, Attaran A. Trading ideology for dialogue: an opportunity to fix international aid for health? Lancet. 2003;361(9364):1216–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12956-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sridhar D, Tamashiro T. Vertical Funds in the Health Sector: Lessons for Education from the Global Fund and GAVI. UNESCO; 2009.

- 52.Waddington C. Does earmarked donor funding make it more or less likely that developing countries will allocate their resources towards programmes that yield the greatest health benefits? Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(9):703–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Government of Tanzania (GoT). Tanzania National Health Account Year 2010 with Sub-Accounts for HIV and AIDS, Malaria, Reproductive, and Child Health. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Department of Policy and Planning, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, United Republic of Tanzania; 2012.

- 54. Koenig S, Rosenquise R. Health Spending in Tanzania: The Impact of Current Aid Structures and Aid Effectiveness. German Foundation for World Population; 2010.

- 55. Bigsten A. Donor Coordination and the Uses of Aid. Goteborg University; 2006.

- 56.Hanefeld J, Walt G. Knowledge and networks - key sources of power in global health: Comment on “Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health”. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(2):119–121. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowen S, Zwi AB. Pathways to “evidence-informed” policy and practice: a framework for action. PLoS Med. 2005;2(7):e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young K, Ashby D, Boas A, Grayson L. Social science and the evidence-based policy movement. Social Policy and Society. 2002;1(3):215–224. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vaillancourt D. Do Health Sector-Wide Approaches Achieve Results? Emerging Evidence and Lessons from Six Countries. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2009.

- 60. Olsson J, Wohlgemuth L. Dialogue in Pursuit of Development. Vol 2. Stockholm: Expert Group on Development Issues; 2003.