Abstract

Recent findings employing the mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) have revealed that muscle satellite stem cells play a direct role in contributing to disease etiology and progression of DMD, the most common and severe form of muscular dystrophy. Lack of dystrophin expression in DMD has critical consequences in satellite cells including an inability to establish cell polarity, abrogation of asymmetric satellite stem cell divisions and failure to enter the myogenic program. Thus, muscle wasting in dystrophic mice is not only caused by myofiber fragility, but is exacerbated by intrinsic satellite cell dysfunction leading to impaired regeneration. Despite intense research and clinical efforts, there is still no effective cure for DMD. In this review, we highlight recent research advances in DMD and discuss the current state of treatment and importantly, how we can incorporate satellite cell-targeted therapeutic strategies to correct satellite cell dysfunction in DMD.

Keywords: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Dystrophin, Mark2, Par1b, Pard3, Satellite Cells, Regenerative myogenesis, Stem cell polarity, Asymmetric division

Rethinking Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

Muscular dystrophies represent a group of heterogeneous genetic diseases that are characterized by progressive skeletal muscle degeneration and weakening. The genes most commonly affected encode for structural proteins that are important for the maintenance of muscle fiber integrity. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severely debilitating and lethal disease affecting approximately 1 in 3,500 male births [1]. Early signs of motor impairment and delays in motor-related milestones manifest between the ages of 2–5. Rapid disease progression and proximal muscle weakening result in patients being wheelchair-bound by the age of 12. Around 18 years of age, patients begin to suffer from cardiomyopathy. Eventual respiratory and cardiac failure are the leading cause of death around the second or third decade of life [2]. While the use of corticosteroids has aided in prolonging patient survival, there is still currently no effective cure for DMD.

DMD, the gene responsible for DMD, is located on the X chromosome and encodes for dystrophin, a 427 kDa rod-shaped protein [3]. Spanning 2.5 megabases and comprised of 79 exons, DMD is the largest known human gene and consequently is prone to mutations [4]. DMD is caused by frame-shifting deletions, duplications and nonsense point mutations that result in either the complete loss or expression of nonfunctional dystrophin protein [5]. Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), which is less common than DMD, is caused by in-frame DMD mutations that generate a semi-functional form of dystrophin resulting in later onset of muscle weakening and a milder disease phenotype.

Dystrophin protein is primarily expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle and to a lesser extent in smooth muscle as well as the brain [6]. Dystrophin functions as an essential component of the large oligomeric dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC) [7, 8]. The DGC acts to connect the actin cytoskeleton of the myofiber to the surrounding extracellular matrix through the sarcolemma. In the absence of dystrophin DGC assembly is impaired which weakens the muscle fibers rendering them highly susceptible to injury. Muscle contraction-induced stress results in constant cycles of degeneration and regeneration [9]. Eventual accumulation of inflammation and fibrosis lead to progressive muscle weakening and loss of muscle mass and function [10].

For the last 20 years, the role of dystrophin and its restoration in mature muscle fibers have been the primary focus of DMD research. Shifting the current paradigm, our laboratory recently showed that dystrophin is expressed in muscle satellite stem cells where it plays a vital role in defining cell polarity (see Glossary) and determining asymmetric cell division [11]. This review highlights the role of satellite cells in DMD, how misregulated cell polarity contributes to the mechanism of disease and what we need to consider in light of these findings as we move forward towards therapeutic treatment of DMD.

DMD Is Also a Stem Cell Disease

Satellite cells are the adult stem cells of skeletal muscle and are defined by their distinct anatomical location between the basal lamina and sarcolemma of the muscle fiber [12]. Satellite cells are responsible for postnatal muscle growth and are indispensable for regeneration in response to muscle injury [13–16]. In healthy muscle, satellite cells remain quiescent in their niche until activated by triggers such as exercise or trauma. Upon activation, satellite cells enter the cell cycle and are able to rapidly proliferate to generate myogenic progenitors, also known as myoblasts, which subsequently fuse together or with damaged myofibers to regenerate and repair the injured muscle [17].

The precise contribution of satellite cells to the mechanism of DMD disease progression has remained an outstanding question within the muscle field. As dystrophin expression was not detected in primary myoblasts [18, 19], it was presumed that satellite cells were also lacking in dystrophin expression. Thus, any effect on satellite cell dysfunction was thought to be an indirect one, owing to the dystrophic environment. One widely accepted view has been the concept of muscle stem cell “exhaustion” caused by repetitive cycles of muscle degeneration and regeneration [20, 21]. This model suggests that satellite cells are ultimately unable to keep up with the high regeneration demand in a dystrophic muscle context, resulting in an eventual loss of regenerative capacity.

Incompatible with the stem cell exhaustion model, multiple studies have reported an increase in the number of satellite cells observed in dystrophic muscle. Analysis of muscle biopsies from DMD patients ranging from 2 to 7 years of age revealed that satellite cell numbers were elevated in dystrophic muscle compared to controls for all age groups [22]. Another study demonstrated that satellite cell content was dramatically and specifically increased in type I muscle fibers of DMD patients with advanced disease [23]. Recent studies examining single myofibers isolated from mdx mice -- a commonly used mouse model for DMD harboring a naturally occurring null mutation in the Dmd gene [24] -- also found elevated satellite cell numbers in fibers from young to old mdx mice, relative to age-matched wild-type controls [11, 25, 26]. These results collectively suggest that the impaired regenerative capacity of dystrophic muscle cannot simply be due to an exhaustion of muscle stem cells.

Notably, the mdx mouse model has a modest dystrophic phenotype and does not accurately recapitulate human DMD disease. Early work examining mdx mice that lack MYOD, a critical myogenic determination factor expressed by committed satellite cells, established that mdx:MyoD−/− mutant mice display severe myopathy, thus demonstrating that loss of MYOD greatly exacerbated the mdx degenerative phenotype [27]. More recently, Sacco and colleagues introduced a telomerase null mutation in mdx mice to generate double knock-out mice that concomitantly lacked dystrophin expression and telomerase activity [21]. Remarkably, these mice exhibit severe muscular dystrophy that more closely resembles human DMD pathology. Satellite cells analyzed from these mice exhibited impaired proliferation and engraftment potential, suggesting that the enhanced severity of the dystrophic phenotype was largely due to the impaired regenerative function of satellite cells. Unlike normal DMD and mdx, however, these mice displayed reduced numbers of satellite cells compared to wild-type control animals.

In line with this rationale, Fukada and colleagues found that mice of the DBA/2 genetic background displayed impaired muscle regeneration and satellite cell self-renewal compared to other mouse strains [28]. They generated DBA/2-mdx mice and reported reduced muscle weight, fewer muscle fibers, increased fibrogenic and adipogenic accumulation and greater muscle weakness compared to the commonly used mdx mice of the C57BL/10 background. Although neither of these approaches directly address the contribution of satellite cell function to DMD disease mechanism, one can nonetheless conclude that disease severity is correlated with the regenerative capacity of endogenous satellite cells. In order to assess the direct contribution of dystrophic satellite cells to DMD, an interesting, yet to be performed experiment would be to genetically ablate satellite cells in mdx mice.

The outstanding regenerative capacity of skeletal muscle is due to the ability of satellite stem cells to undergo myogenic commitment generating cell progenitors necessary for muscle repair, and, to undergo self-renewal for the maintenance of the satellite cell pool [17]. Self-renewal is achieved via symmetric cell expansion (generating two identical daughter stem cells) or through an asymmetric cell division (generating both a stem cell and a committed progenitor daughter cell) (Figure 1). Work from multiple groups has demonstrated that satellite cells are a heterogeneous population of stem cells and committed progenitors that differ in their propensity to either self-renew or differentiate upon activation [reviewed in 29].

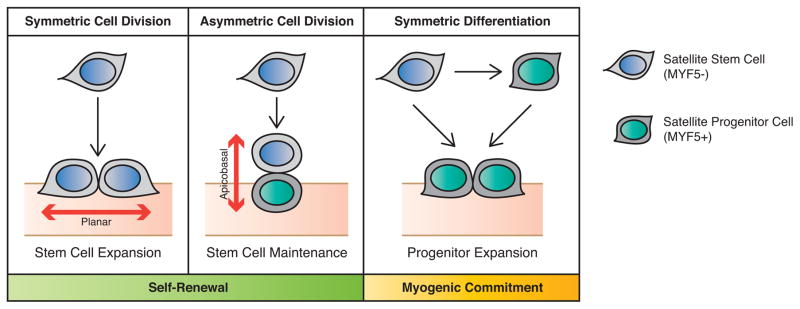

Figure 1. Modes of Satellite Stem Cell Division.

Satellite stem cells can self-renew via symmetric or asymmetric cell divisions. A symmetric cell division along the planar axis (with respect to the myofiber) generates two stem cell daughters. Asymmetric cell divisions along the apicobasal axis give rise to a stem cell and a committed myogenic progenitor cell. Alternatively, satellite stem cells can directly express myogenic commitment factors (such as MYF5) to commit to the myogenic lineage and expand the progenitor population that will participate in muscle repair.

Employing transgenic mice carrying Myf5-Cre and R26R-YFP Cre-reporter alleles, our laboratory previously determined that a subpopulation of satellite cells have never expressed the myogenic commitment transcription factor MYF5 [30]. MYF5− satellite stem cells demonstrate superior engraftment potential and are capable of repopulating the satellite cell niche of recipient muscle, whereas MYF5+ satellite cells spontaneously differentiate and fail to engraft as satellite cells upon transplantation into muscle [30]. Importantly, MYF5− satellite stem cells from Myf5-Cre:R26R-YFP mice undergo symmetric cell division and asymmetric cell divisions (giving rise to both MYF5− and MYF5+ daughter cells) (Figure 1) [30].

The molecular mechanisms underlying asymmetric cell division are remarkably conserved between organisms as well as different stem cell types. In general, polarization of the cell cortex and specification of the orientation of the mitotic spindle are critical steps for the asymmetric localization of cell fate determinants (reviewed in [31]). Current understanding of the upstream events leading to an asymmetric cell division is based on extensive studies in Drosophila megalonaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. The formation of the evolutionarily conserved Par complex, consisting of Baz (Bazooka, the Drosophila homolog of Partitioning defective protein 3, PARD3), Par-6 and atypical Protein Kinase C (aPKC), is essential for the progression of asymmetric division in neuroblasts, which gives rise to both a committed neurocyte and a stem cell neuroblast (Figure 2) [32].

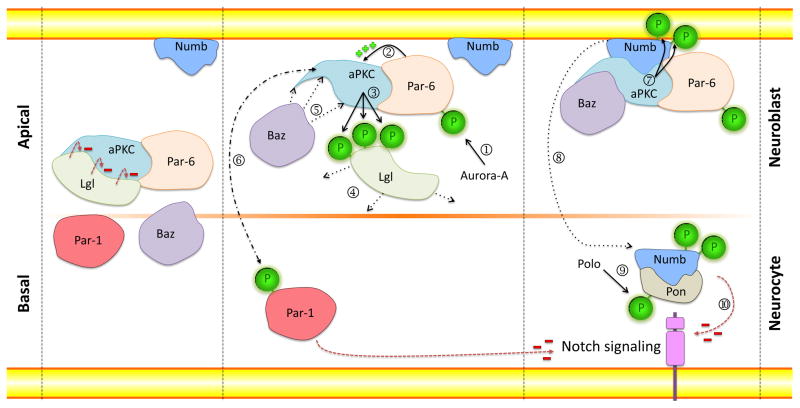

Figure 2. Classical Model for the Establishment of Asymmetric Stem Cell Division during Neurogenesis in Drosophila.

During interphase, the Par proteins are equally distributed in the cytoplasm. The binding of Lgl to aPKC inhibits its activity. Upon activation, Aurora kinase phosphorylates Par-6 (➀) leading to the activation of aPKC (➁) which phosphorylates Lgl (➂) and forces its release (➃). Baz binds aPKC and completes the assembly of the Par complex (➄). The Par complex can now phosphorylate Par-1 (➅) and Numb (➆), leading to their relocalization to the opposite pole of the cell (➇). After activation by Polo kinase, Pon binds phosphorylated Numb (➈) and together with Par-1, act to inhibit Notch signaling (➉), thus differentially controlling fate determination in the two daughter cells.

During interphase, aPKC and Par-6 form a complex with the protein Lethal giant larvae (Lgl), a cytoskeletal protein that binds and inhibits aPKC. Upon activation, Aurora-A kinase phosphorylates Par-6 which in turn induces aPKC to phosphorylate Lgl in Drosophila [33]. Phosphorylated Lgl is released from aPKC and thereby allows the PDZ domain-containing protein Baz to join the complex. This alters aPKC substrate specificity and allows the phosphorylation of Numb, an inhibitor of the Notch signaling pathway, and its release from the apical cortex [34]. Phosphorylated Numb then localizes to the basal side of the cell assisted by the adaptor protein Partner of Numb (Pon), whose activity is dependent on phosphorylation by Polo kinase (Figure 2) [35]. Live-imaging experiments in Drosophila conducted by Couturier et al. [36] have shown that the asymmetric localization of Numb is responsible for differential Notch signaling activity in the two daughter cells and for generating cell fate diversity. Using transgenic flies expressing Notch tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP), the authors were able to follow Notch-GFP distribution in dividing sensory organ precursor cells. Asymmetric expression of Notch-GFP was detected at the apical side of the cytokinetic furrow, the interface between two sibling cells. In the absence of Numb function, Notch localization was altered, demonstrating that Numb controls the subcellular localization of Notch during asymmetric cell division [36].

In addition to the aPKC/Baz(PARD3)/Par-6 Par complex, the serine/threonine kinase Par-1 is also implicated in regulating cell polarity in various biological contexts. For example, in the C. elegans embryo, Par-1 together with Par-6 are essential in establishing the anterior-posterior polarity of the embryo through asymmetric positioning of the mitotic spindle [37]. The Par complex and Par-1 exhibit complementary localizations along the polarity axis in a variety of cells [37–39]. For instance, in mammalian epithelial cells the Par complex localizes at the apical membrane in contrast with PAR1 (also known as MAP/Microtubule Affinity-Regulating Kinase 2, and hereafter referred to as MARK2 in the text) at the basolateral membrane, thus defining the apicobasal axis [39]. Depending on the biological system, Par-1/MARK2 acts either upstream of the Par complex or is targeted by it (Figure 2) [38, 39].

Orientation of the mitotic spindle and establishment of cell polarity are tightly linked. Baz (PARD3) recruits the adaptor protein Inscuteable to the apical region which in turn interacts with Partner of inscuteable (Pins) [40]. Consequently, Pins recruits the microtubule-associated and dynein-binding protein Mud (the Drosophila homolog of NUMA) [41], which binds to the centrosome and links astral microtubules to the apical complex thereby determining the apicobasal orientation of the mitotic spindle. Centrosomes organize microtubules within the cell to establish cell polarity, subcellular localization of organelles and bipolar spindle formation. The temporal coordination of spindle positioning is dependent on the Aurora and Polo kinases [35, 42, 43], however, the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Importantly, the decision to undergo symmetric or asymmetric self-renewal is a critical step in satellite cell fate determination and deregulation of this process has detrimental consequences on the execution of the muscle regeneration program (Figure 3). For instance, a loss in the ability of satellite stem cells to undergo symmetric cell expansion is an underlying cause of age-related decline in the regenerative capacity of satellite cells in mice [44]. In contrast, uncontrolled self-renewal could result in the overproduction of stem cells and potentially lead to tumorigenesis (see section below: Consequences of Impaired Polarity). Lastly, long-term deficits in the ability to generate differentiated progenitors can ultimately lead to organ failure. Along these lines, recent work has revealed how interference in the homeostasis between stem cells and committed progenitors, as well as the described intrinsic satellite cell dysfunction contribute to DMD pathology [11].

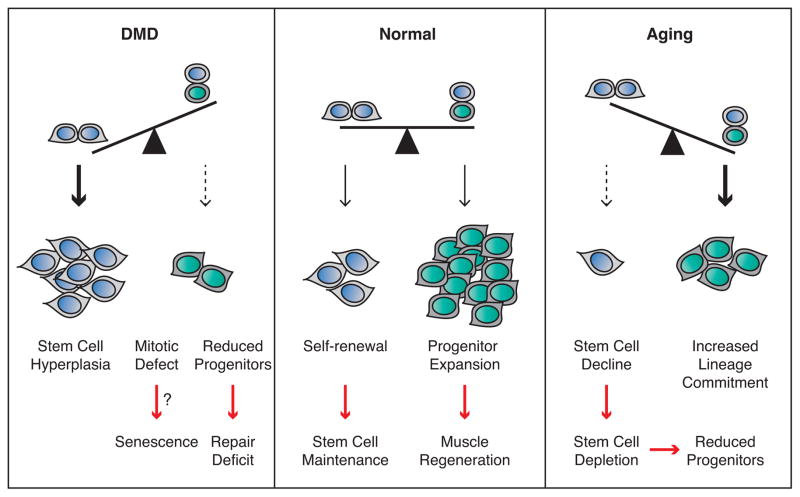

Figure 3. Efficient Muscle Regeneration and Tissue Homeostasis Are Dependent On a Balance Between Symmetric and Asymmetric Satellite Stem Cell Divisions.

Upon muscle injury within a healthy muscle, symmetric satellite cell expansion maintains the stem cell pool, while asymmetric cell divisions generate myogenic progenitors that will undergo expansion to regenerate the damaged tissue. In the context of aging, satellite stem cells favor commitment over self-renewal (increased asymmetric and reduced symmetric cell divisions) resulting in a gradual loss of stem cells. Over time, satellite stem cell decline and reduced entry into the cell cycle results in reductions of both stem and progenitor populations and an inability to efficiently perform muscle regeneration. In DMD, the loss of dystrophin-dependent polarity cues prevents satellite cells from undergoing asymmetric cell division. Shifting the balance towards symmetric stem cell division results in an increased number of satellite stem cells. An inability to perform asymmetric divisions and the associated mitotic defects may force the cells to enter a senescent state. Progressive depletion of committed progenitor cells over repetitive cycles of muscle degeneration-regeneration ultimately leads to muscle weakening.

Impaired Polarity Leads to Intrinsic Satellite Cell Dysfunction

Unexpectedly, RNA-Seq and microarray analysis of prospectively isolated satellite cells have revealed that Dmd is highly transcribed in satellite cells [11]. Immunofluorescence analysis with anti-dystrophin antibodies in both FACS-sorted satellite cells and satellite cells cultured on myofibers has also confirmed that the dystrophin protein is indeed expressed in activated satellite cells [11]. Interestingly, dystrophin protein expression has been found to be polarized in satellite cells and to be at its highest when the cells are about to undergo cell division [11].

It was previously reported that in mammalian cells, dystrophin interacts with the cell polarity-regulating kinase MARK2 at the muscle fiber membrane, an interaction mediated by the 8th and 9th spectrin-like repeats of dystrophin [45]. The biological relevance of this interaction, however, had not been explored. Of note, cell polarity proteins have been previously implicated in the determination of asymmetric cell divisions in satellite cells [46, 47]. Analysis of satellite cell divisions on single myofibers isolated from mice has revealed that asymmetric localization of PARD3 in divided satellite cells leads to the asymmetric activation of p38α/β and expression of the myogenic determination factor MYOD in committed daughter cells [46]. The absence of PARD3 expression and lack of p38α/β activation have also been found to lead to self-renewal and return the satellite stem cell to quiescence [46]. The Scribbled Planar Cell Polarity Protein (SCRIB) has been shown to be both asymmetrically and symmetrically polarized in dividing satellite cell couplets on cultured myofibers from mice [47]. SCRIB protein levels were found to dictate satellite cell fate; low SCRIB expression was identified in highly proliferative cells that resisted self-renewal, while high SCRIB expression corresponded with cells committed to myogenic differentiation [47].

This study confirmed that dystrophin interacts with MARK2 in satellite cells via an in situ proximity ligation assay [11]. Dystrophin and MARK2 expression were found to be polarized in a subset of activated satellite cells with a corresponding polarized distribution of PARD3 at the opposite pole. In mdx satellite cells, dystrophin deficiency resulted in reduced expression of MARK2 and a loss of PARD3 polarization. In accordance with the abnormal expression of polarity proteins, a significant reduction in asymmetric satellite stem cell divisions was observed in cultured myofibers isolated from mdx mice. Moreover, abrogation of asymmetric stem cell division resulted in the gradual loss of myogenic progenitors and impaired muscle regeneration [11].

As previously mentioned, alignment of the mitotic spindle by centrosomes to determine the axis of cell division (apicobasal or planar) is a key event determining asymmetric cell division. Previous work has established that asymmetric MYF5−/MYF5+ satellite cell divisions have been found along the axis apicobasal to the myofiber in contrast to symmetric MYF5− planar divisions [30]. In mdx satellite cells, the loss of cell polarity has resulted in defective mitotic spindle orientation and a significant reduction in the number of apicobasal oriented spindle poles, thus reflecting impairment in asymmetric cell division (Key Figure, Figure 4). Furthermore, mdx satellite cells have been reported to exhibit mitotic defects, including abnormal expression of phosphorylated Aurora kinase, centrosome amplification, and impaired cell division kinetics [30]. Thus, these studies demonstrate that dystrophin is essential for the establishment of polarity and apicobasal alignment of the mitotic axis which is required for proper mitotic progression of asymmetric satellite stem cell divisions.

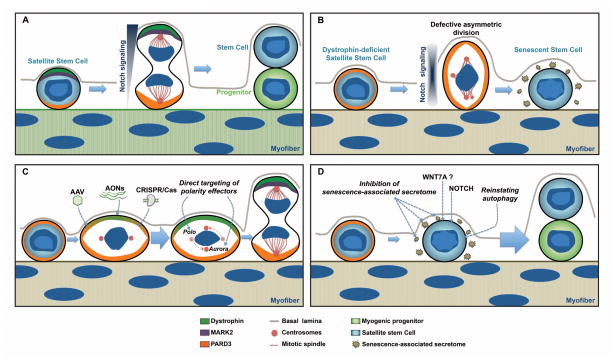

Key Figure, Figure 4. Consequences of Cell Polarity Defects and Therapeutic Strategies to Restore Satellite Cell Function in Dystrophic Satellite Cells.

A) Normal satellite stem cells undergo asymmetric division upon dystrophin-dependent polarization of MARK2 and PARD3 to opposite sides along the apicobasal axis of the dividing cell. Cell fate determinants, such as mediators of Notch signaling, are asymmetrically distributed during mitosis to enforce different cell fates (stem cell self-renewal and myogenic commitment).

B) In dystrophin-deficient satellite cells, the expression of MARK2 is downregulated and PARD3 is equally distributed within the dividing cell. In the absence of polarity cues and abnormal mitotic progression, satellite stem cells undergo cell cycle arrest and may enter senescence.

C) Therapeutic approaches to restore cell polarity in DMD include AAV-mediated gene delivery of dystrophin or utrophin, in vivo genome editing with CRISPR/Cas, and direct pharmacological targeting of cell polarity effectors.

D) Therapeutic approaches to restore satellite cell function include treatment with WNT7a, inhibition of senescence-associated secreted factors and stimulating the autophagy pathway to prevent senescence.

For the first time, a direct role for dystrophin regulating satellite cell function has been described, providing a clear link between dystrophic satellite cells and loss of muscle regenerative capacity in DMD. Intriguingly, gene expression comparison analysis has revealed that Dmd can be expressed over 4-fold higher in satellite cells when compared to differentiated myotubes [11]. One might speculate that in addition to ongoing damage to myofibers, the lack of dystrophin in satellite cells represents a significant contributing factor in the manifestation of the DMD phenotype. To properly discriminate the contribution of dystrophin in mature fibers when compared to satellite cells, muscle regeneration experiments involving conditional deletion of Dmd will need to be performed (e.g. mice with Dmd floxed alleles using either muscle or satellite cell-specific Cre-promoters).

Consequences of Impaired Polarity

Evidence in Other Disease Contexts

Dysfunction of asymmetric cell division and cell polarity has been established in other disease mechanisms. Accumulating evidence suggests that disruption of asymmetric cell division is involved in tumorigenesis. Indeed, mutations in key regulators of asymmetric cell division, such as LGL, NUMB and Aurora or Polo kinases can cause cancer-associated phenotypes in both fly and mouse models (reviewed in detail in [48]). Importantly, natural genetic mutations of key regulators of asymmetric cell division have been found in human tumors [48]. For instance, protein expression and/or localization of PARD3 and PAR6 are disrupted in various types of cancers, including bladder, breast, esophagus, head and neck, and lung cancers, as well as melanoma and glioblastoma [49–52]. In addition, reduced protein expression of NUMB [53–55], but overexpression of Aurora and/or Polo kinases [56–68] have been found to be common features of many tumors.

Related to their defect in cell polarity, another hallmark of cancer cells is the duplication of their centrosomes. Aberrant centrosome number and abnormal mitotic spindles strongly correlate with chromosome instability [69]. Recent work in p53−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) has revealed that loss of p53 leads to Aurora A and Polo-like Kinase 1 (PLK1) hyperactivity at the centrosome resulting in abnormal spindle geometry and leading to early centrosome disjunction, as well as the formation of aberrant spindles that result in inaccurate separation of chromosomes, and ultimately, apoptosis [70]. The multipolar spindle state, however, may only be transient as cells can adapt to the extra number of centrosomes by clustering the centrosomes into two principal poles during mitosis, a process known as bipolar spindle assembly [71]. Clustered bipolar spindles are evidently not perfect and cells exhibit increased frequency of lagging chromosomes during anaphase [71]. Interestingly, the ability to cluster supernumerary centrosomes into a bipolar mitotic spindle array is a conserved mechanism also used by non-transformed cell types [72, 73], and relies on the spindle assembly checkpoint activity, a quality control mechanism which delays mitotic progression until the formation of a bipolar spindle [see 74 for a detailed mechanism]. Indeed, it will be interesting to determine if clustering of supernumerary chromosomes occurs in mdx satellite cells, which could explain their delay in mitosis and how a minor percentage of satellite cells are able to undergo asymmetric cell division.

In flies, extra centrosomes compromise the spindle orientation and thereby disrupt the asymmetric division of neural stem cells, leading to excessive expansion of the neural stem cell pool and resulting in tumorigenesis [75]. Of note, a recent report found that dystrophin acts as a tumor suppressor gene in human myogenic tumors including gastrointestinal stromal tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma [76]. This finding is consistent with the role of dystrophin in promoting cell polarity and asymmetric satellite stem cell divisions which would furthermore suggest that treatments to repair the polarity deficit in dystrophic satellite cells might also have implications in the treatment of myogenic cancers.

Contribution to Other Aspects of Dmd Pathology

Cognitive impairment is observed in approximately 30% of boys suffering from DMD, although the precise causes are unclear. Specific isoforms of dystrophin are expressed during neural development and in specific regional neuronal subpopulations within the mature brain [77]. We propose that polarity deficiency in the brain could explain the neurological effects associated with DMD. Indeed, polarity deficits during neural development have drastic effects on the brain and have been described for microcephaly, a neuro-developmental disorder characterized by brain size reduction at birth. The genetic nature of the disease is heterogeneous. However, most of the mutations identified affect centrosome assembly and integrity or spindle orientation associated genes [78]. In addition, a direct correlation with centrosome amplification and microcephaly has been documented [73]. Lissencephalic patients also present a brain malformation characterized by the absence, or incomplete development of specific regions of the cerebral cortex, causing the brain’s surface to appear unusually smooth. The two most commonly mutated genes in patients with lissencephaly are LIS1 and DCX [79]. Of note, both genes are involved in proper positioning of the mitotic spindle and their dysfunction leads to premature asymmetric divisions and to a reduction in the neural stem cell pool [78, 79].

In support of the hypothesis that dystrophin deficiency may result in polarity defects in the brain, a recent study has demonstrated that expression of dystrophin-associated protein complexes such as aquaporin-4, potassium channel Kir4.1, α- and β-dystroglycan, α-syntrophin, and short dystrophin Dp71isoforms, was mislocalized and diffused in the cytoplasm of mdx neural stem cells, in contrast to their polarized distribution on the plasma membrane of control neural stem cells [80]. Interestingly, decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis were also observed in mdx neural stem cells [80], thus providing an explanation for the altered glial maintenance and differentiation observed in mdx mice [81].

Huntington’s disease is another neurodegenerative pathology where cell polarity is affected. Clinical features of Huntington’s include dementia and cognitive defects together with an impairment in muscle coordination [82]. The pathology is caused by mutations in the N-terminal region of the Huntingtin protein, a multifunctional protein involved in the control of vesicle trafficking, autophagy, transcription, as well as coordination of cell division. In dividing cells, Huntingtin is targeted to the spindle poles through its interaction with dynein, where it promotes the accumulation of NUMA and LGN [82]. Huntingtin is also essential for the cortical localization of dynein, dynactin, NUMA, and LGN by regulating kinesin 1-dependent trafficking of these factors along astral microtubules [83], and is required to ensure the microtubule-dependent apical vesicular translocation of PARD3-aPKC during epithelial morphogenesis in mice [83]. As Huntington’s is a late adult onset disease, these findings raise the possibility that early defects in cell polarity and spindle orientation during neural development can result in progressive degeneration with symptoms that present later in life. In parallel with DMD, it would be interesting to determine if dystrophin plays a role in the establishment of both embryonic myogenic and neural progenitors.

Cardiomyopathy is associated with late stages of DMD and data in support of cell polarity defects in cardiac tissue are less established. In recent years, a correlation has been made between dysregulation of the planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling pathway and cardiopathies [84]. In both invertebrates and vertebrates, normal cardiac development is dependent on PCP signaling which contributes to proper cardiac specification in the mesodermal germ layer [84]. Several studies have highlighted the essential role of two PCP genes Scrib and Vangl2 in cardiac development. SCRIB function is required for normal VANGL2 localization in the developing mouse myocardium and both are required for cardiomyocyte polarity and organization [85, 86]. SCRIB loss of function during early mouse development does not prevent the formation of an intact heart tube, but does however, affect the organization of the cardiomyocytes within it [86]. Taken together, these studies support the notion that disruption of the polarity axis in dividing cells during development may help explain the degeneration observed in multiple tissues in DMD.

Fate of Dystrophic Satellite Cells

In light of these recent findings, an important question that remains unaddressed is to determine what the fate of dystrophic satellite cells that are unable to undergo proper cell division is. In accordance with the observation that mdx satellite cells exhibit a reduced ability to commit to the myogenic program [11], another recent study found that satellite cells from mdx mice have reduced myogenic potential and initiate a fibrogenic program [87]. It is conceivable that the satellite cell dysfunction in DMD contributes to multiple pathological aspects of the disease, including reduced muscle regenerative capacity and enhanced fibrosis.

The elevated numbers of satellite cells found in DMD muscle, however, would suggest that these dysfunctional satellite cells persist but are unable to participate in muscle repair. Due to the centrosome amplification observed in mdx satellite cells, one hypothesis is that these cells undergo mitotic catastrophe and default to senescence, where cells remain in an irreversible state of cell cycle arrest. Notably, a recent study showed that mouse satellite cells that fail to pass the spindle assembly checkpoint undergo cell cycle arrest in G1 and resist differentiation [88]. Additionally, overexpression of Aurora kinase, which is commonly observed in cancer, induces abnormal spindle formation causing cells to bypass the spindle checkpoint and undergo apoptosis or senescence, as demonstrated in both invertebrate and vertebrate models [89].

The accumulation of senescent cells is associated with aging, and such cells have been described to secrete various proteases, growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines that compromise the function of neighboring cells. Numerous studies have provided compelling evidence that reactive oxygen species (ROS) contribute to the pathophysiological progression of muscular dystrophies. Indeed, in muscles biopsies from DMD patients, a two-fold increase in the levels of carbonyl groups (C=O) has been observed [90], in addition to ROS-induced protein damage, as well as increased levels of isoprostanes [91], an indication of lipid peroxidation. ROS lead to the activation of the NF-kB pathway, resulting in an upregulation of the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which have been found to be highly expressed in muscles from mdx mice, even before the phenotypic onset of muscular dystrophy [92].

Interestingly, mdx myotubes cultured in vitro have not been shown to be more sensitive to ROS-induced cell death when compared to wild-type control myotubes [93]. By contrast, undifferentiated myoblasts from mdx and wild-type muscles were found to be equally sensitive to ROS-induced oxidative stress [93]. Dystrophin is not expressed in myoblasts but is found in wild-type myotubes, hence, this strongly suggests that the absence of dystrophin in mdx myotubes is the primary cause of the increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. As dystrophin is highly expressed in activated muscle stem cells [11], we hypothesize that the absence of dystrophin in satellite cells from DMD patients could result in an accumulation of oxidative stress within the cell and thus, contribute to a senescent or apoptotic fate. Further analysis of the secretome of dystrophic satellite cells needs to be performed in order to examine if these cells secrete factors that could directly contribute to DMD disease progression.

Congruent with the senescence hypothesis, muscular dystrophy and sarcopenia, an aging-related pathology characterized by muscle atrophy and decreased muscle strength, share common histopathological traits [reviewed in 94]. Intriguingly, recent work from the Muñoz-Cánoves’ lab has shown that the autophagy pathway is required to prevent senescence in satellite cells and is disrupted in aged satellite cells in mice [95]. Autophagy is an ubiquitous process by which the cell eliminates damaged intracellular components such as organelles and misfolded proteins, which are delivered to the lysosome for degradation and recycling of nutrients. Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests that basal autophagy is critical for maintaining stem cell function in multiple stem cell types. Failure of autophagy in geriatric mouse satellite cells has been shown to result in the accumulation of damaged proteins and subcellular organelles, including mitochondria, causing cells to enter senescence [95]. Moreover, an inability to remove damaged mitochondria leads to an increase in the cellular concentrations of ROS, which affects the homeostasis and stemness of the muscle stem cells [95]. Consequently, the capacity to regenerate damaged myofibers and to replenish the stem cell pool is severely impaired in aged mice.

Compromised autophagy has been associated with neurodegenerative diseases [recently reviewed in 96]. Importantly, impairment of the autophagy pathway has been described in the Tibialis anterior muscle of mdx mice [97] and accumulation of damaged organelles and marked defects in autophagy have been observed in muscles from DMD patients [98]. Thus, early dysfunction of the autophagy pathway in dystrophin-deficient satellite cells could favor their entry into senescence and provide a supplemental explanation for the elevated number of satellite cells not participating in muscle regeneration while concomitantly, contributing to the progression of the disease.

Restoring Satellite Cell Function in DMD

Current Strategies Do Not Target Satellite Cells

While progress has been made in the past 5 years with respect to potential treatments for DMD (Box 1), current strategies are focused on treatment of skeletal muscle and do not take satellite cells into consideration. Gene therapy to reinstate DMD expression would correct the primary genetic defect and has been made feasible with the recent development of adeno-associated vectors (AAVs) to mediate gene delivery. While it is clear that the recombinant AAV serotype 6 (AAV6) can efficiently transduce skeletal muscle [99, 100], a study comparing the ability of different AAV serotypes to transduce satellite cells and myofibers in vivo found that AAV6 was ineffective at transducing satellite cells in mice [101]. Satellite cells positive for transduction were found only when treated with the AAV8 serotype, and in that case, only a mere 5% of satellite cells were transduced. It remains unclear why satellite cells are refractory to AAV transduction. However, development of second-generation AAVs that can effectively target satellite cells would greatly improve therapeutic efficacy.

Box 1. Strategies to Restore Satellite Cell Function in DMD.

Gene delivery of dystrophin or utrophin – optimize strategies to ensure satellite cell delivery

Satellite cell transplantation – autologous transplantation of genetically-corrected patient derived myogenic progenitor cells

In vivo genome editing with CRISPR/Cas – optimize strategies to ensure satellite cell delivery

Pharmacological approaches to restore cell polarity – targeting key mediators of cell polarity or downstream cell fate determination pathways (Notch signaling)

WNT7a treatment – mechanism of action in dystrophic muscle needs to be elucidated

Elimination of dysfunctional satellite cells – selectively target senescent cells and reinstate the autophagy pathway

Another restriction to AAV-mediated gene therapy is the size limit of the packaging vector. Due to the large size of the dystrophin transcript (14 kbps), researchers have had to compromise by designing smaller versions of DMD (termed mini- or micro-dystrophin) containing essential functional domains based on gene transcripts expressed in the milder BMD disease [102, 103]. While expression of these dystrophin-truncates in mice appear to improve muscle strength and histology in vivo, the predicted rescue effect in humans would at best, mimic a BMD milder disease state. Treatment would have to be life-long and it remains unclear how long-term AAV therapy would be tolerated. Moreover, these dystrophin-truncates lack spectrin-like repeats 8 and 9 that mediate the interaction between dystrophin and MARK2 [45]. Thus, a critical step in restoring the polarity deficit in dystrophic satellite cells would be to reinstate a form of dystrophin which contains these repeats.

Exon skipping with antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) is another genetic approach that holds great promise for the treatment of DMD and has already been tested in Phase I and II clinical trials [104]. Due to the nature of DMD mutations (~83% are frame-shifting deletions), exon skipping would benefit a majority of DMD patients. AONs hybridize to complementary regions of the pre-mRNA and interfere with the splicing machinery to induce skipping of the targeted exon in order to restore the internal reading frame, thereby generating an internally truncated form of dystrophin [105]. The caveat, however, is that treatment is highly mutation-specific and thus, would require the need for personalized medicine and the development of specific AONs on a case-by-case basis. Currently, poor cellular uptake of AONs is a limiting factor and uptake by satellite cells will need to be assessed.

In DMD, an alternative approach to restoring dystrophin deficiency is to upregulate the expression of utrophin. Utrophin protein shares 80% sequence homology with dystrophin and is normally expressed at the neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions in mammals [106–108]. In both mdx mice and DMD patients, utrophin protein expression is upregulated throughout the sarcolemma of muscle fibers [107, 108]. Different strategies are currently considered to enforce the expression of utrophin in dystrophic muscles, such as treatment with the nerve-derived growth factor heregulin, with pharmacological modulation of the calcineurin–NFAT signalling pathway or, with the administration of L-arginine (reviewed in [109]). Interestingly, utrophin is able to interact with MARK2 [45], whose protein expression is downregulated in the absence of dystrophin [11]. Thus, it will be interesting to investigate if utrophin protein expression specifically in satellite cells is able to compensate for the absence of dystrophin by rescuing the expression of MARK2 and restoring asymmetric cell divisions.

With respect to pharmacological approaches, administration of corticosteroids are the current standard of care for DMD, as they are well tolerated and improve patient quality of life [110]. Long-term therapy delays the loss of ambulation by 2–5 years and improves cardiopulmonary function, leading to prolonged life expectancy. Benefits resulting from such therapy are likely related to the modulation of NF-κB, which is involved in the expression of pro-inflammatory modulators [111]. Long-term corticosteroid treatment, however, is associated with undesirable side-effects such as weight gain, risk for hypertension and loss of bone density, among others [110]. Stimulation of muscle hypertrophy is also currently being investigated through the administration of different drugs either inhibiting myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle mass, or stimulating the IGF-1 pathway, which induces satellite cell proliferation and differentiation [112]. Several other strategies to target fibrosis (TGFβ inhibitors) [113], oxidative stress [114] or ischemia [115] are also being explored. Recently, histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDAC) have been found to ameliorate the dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice. Indeed, HDAC inhibitors promoted the transcription of muscle-specific transcriptional activators [116], such as MYOD and MEF2C, and restored normal muscle morphology, myofiber size and strength in mdx mice [117]. As such, clinical studies are currently ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of all of these compounds. These pharmaceutical approaches, however, mainly aim to manage DMD symptoms and to suppress the inflammatory response [118], yet do not address satellite cell dysfunction.

Potential Strategies to Correct Polarity Deficiency and Satellite Cell Function

In recent years, advances have been made in the ex vivo expansion of myogenic progenitor cells, hence renewing optimism for cell transplantation therapy in the treatment of neuromuscular disorders. Expansion of satellite cells on bioengineered hydrogel, which has been shown to mimic skeletal muscle elasticity, give rise to cells with improved self-renewal and engraftment potential when compared to satellite cells expanded on plastic dishes [119]. Moreover, improvements in myogenic differentiation protocols of embryonic stem (ES) cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells now make it feasible to model DMD and correct patient cells for the purposes of autologous cell transplantation therapy [120, 121]. Interestingly, one study reported that when myogenic cells were derived from mdx ES cells and subjected to myogenic differentiation, the generated myofibers did not exhibit membrane fragility or increased membrane permeability but rather, exhibited an abnormal myofiber branching phenotype [120]. This finding further challenges the aforementioned paradigm and suggests that muscle fiber weakness cannot be the only cause for DMD disease progression.

Another exciting avenue of therapeutic research is the use of in vivo genome editing tools to directly correct disease-causing mutations. Three independent studies recently demonstrated the potential of delivering the CRISPR (Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)/Cas (CRISPR-associated) system in young mdx mice to excise the mutated exon 23 and partially restore dystrophin expression [122–124]. The approach utilized by the three groups was similar; delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 was mediated by AAVs (AAV serotypes 8 or 9) using a 2 vector system to separately introduce the guide RNA and Cas9 endonuclease via local and systemic delivery. All groups reported partial rescue of dystrophin expression in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Importantly, minimal off-target effects were observed. Muscle function and biochemistry were also improved in the mdx mouse, although not to the levels of wild-type mice. Of note, the study performed in the Wagers lab reported Dmd editing in a subset of satellite cells in treated mdx mice; these cells maintained their myogenic potential and were capable of giving rise to differentiated myotubes [122]. As discussed previously, AAVs do not efficiently target satellite cells, a limitation that requires further consideration. Nonetheless, these studies demonstrate exciting proof-of-principle that genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 can be utilized in vivo to repair mutations in genetic disorders.

Pharmacological Approaches to Restore Polarity

In the cancer field, cancer stem cells are defined as cells within a tumor that have the capacity to self-renew and generate the heterogeneous lineages of the cancerous cells that make up the tumor [125]. Tumors therefore are composed of differentiated cells with limited long-term proliferative potential and a minor subpopulation of cancer stem cells that are mostly quiescent. This model provides an explanation for the resistance of tumors to chemo- and radio-therapies which target proliferating cells, and why tumor relapse is often observed after treatment. Thus, identification of molecules involved in asymmetric cell division and the development of drugs targeting these molecules may potentially succeed in eliminating cancer stem cells. For example, a recent study showed that targeting PLK1 (a regulator of cell polarity) simultaneously with a pharmacological inhibitor of the MAPK pathway, was effective against human patient-derived glioblastoma cells usually resistant to standard therapies [126].

Additionally, Notch signaling, which is important for the specification of asymmetric fate, is impaired in muscular dystrophy [25]. As Notch signaling occurs downstream of the PAR proteins [127], we speculate that dysregulation of the Notch pathway is a direct consequence of the loss of cell polarity in the absence of dystrophin. Interestingly, a recent study found that Jagged1, a regulator of the Notch pathway, was specifically overexpressed in two golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) dogs that escaped the DMD phenotype [128]. Myoblasts derived from the muscles of these escaper dogs displayed greater proliferative capacity, consistent with previous findings demonstrating that overexpression of Jagged1 protein stimulates cell proliferation of mouse cardiomyocytes [129]. Interestingly, ectopic expression of Jagged1 in a DMD zebrafish model was sufficient to rescue the dystrophic phenotype [128]. Mechanistically, it still remains to be determined how Jagged1 improves DMD and how Jagged1 expression affects satellite cell function. As Notch signaling is directly involved in the specification of asymmetric cell fate determinants, it seems plausible that the ameliorative effects of Jagged1 are a result of restoring asymmetric cell division in dystrophic satellite cells.

Wnt7a Treatment Ameliorates DMD

Protein expression of the Wnt ligand WNT7a has been shown to be upregulated upon skeletal muscle injury in mice [130]. Further analysis found that WNT7a stimulated the symmetric expansion of satellite stem cells through the planar cell polarity pathway via polarized distribution of VANGL2, a core component of the PCP pathway, at the two poles of dividing daughter cells. Additionally, WNT7a injection into damaged muscles significantly improved regeneration in both healthy and mdx mice [130, 131]. Mechanistically, in injured muscles from wild-type mice, WNT7a enhanced muscle regeneration by transiently expanding the stem cell population, subsequently generating more committed progenitor cells through apicobasal asymmetric divisions [130]. In dystrophic mice, treatment with WNT7a also resulted in higher numbers of satellite cells and stimulated the hypertrophy pathway [131]. The mechanism of action by which WNT7a enhances the number of satellite cells in a dystrophic context has yet to be elucidated. We hypothesize that WNT7a may induce an alternate polarity in satellite cells under a dystrophic context in order to rescue the impairment in asymmetric divisions. Interestingly, WNT7a and VANGL2 are involved in asymmetric divisions of mouse cortical progenitors through the establishment of spindle-size asymmetry [132]. Thus, the polarity induced by WNT7a may depend on the cellular context. How the absence of dystrophin affects WNT7a mechanisms will need to be addressed.

Strategies to Eliminate Senescent Satellite Cells

Finally, if dystrophic satellite cells are entering a state of senescence, strategies to eliminate these cells may have therapeutic benefit for DMD. Normally, senescent cells express ligands that are targeted by the immune response in order to induce their own clearance [133]. In aging or pathological conditions, however, a decline of the immune system in both human and experimental models is accompanied by an inability to effectively clear senescent cells [134]. Indeed, elimination of senescent cells in mice via genetic inducible clearance of p16Ink4a-positive cells, an universal marker for senescent cells, has provided proof-of-principle validation that this strategy can ameliorate the development of aging-associated disorders [135]. By deleting p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells, Baker and colleagues demonstrated that they could delay onset of age-related pathologies such as the loss of adipose tissue, sarcopenia and development of cataracts [135]. In the context of muscular dystrophy, further studies will need to be performed in order to investigate the secretome of senescent satellite cells and identify senescence markers.

From another angle, glucocorticoids, the current standard treatment for DMD, have been found to decrease the production and secretion of selected senescence-associated secretory components in human fibroblasts, including several pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF and MCP-2 [136]. Additionally, a new class of drugs termed senolytics, which selectively kill senescent cells, is currently being developed [137]. These small molecules are designed to target pro-survival proteins of the BCL-2 family, which are upregulated in senescent cells, in order to induce cell death via apoptosis [138]. BCL-2 pro-survival proteins also play a role in negatively regulating autophagy [139]. Thus, stimulation of the autophagy pathway would also be predicted to prevent satellite cell senescence and promote the proper function of satellite cells [95, 140].

Concluding Remarks

The discovery that dystrophin is expressed in satellite cells and functions to establish apicobasal polarity for asymmetric satellite stem cell divisions has provided new mechanistic insight into the etiology of DMD. Challenging the notion of muscle stem cell exhaustion, we now have evidence of a clear and direct contribution of satellite cell dysfunction to the pathological progression of DMD. While the fate of these persistent satellite cells in DMD will need to be examined, these findings highlight the critical need for DMD therapeutic strategies to target muscle satellite stem cells (Box 1) and reestablish polarity in order to facilitate entry into the myogenic program (see Outstanding Questions). Such therapeutic approaches may indeed hold a promising potential for alternate methods of treatment in DMD which may supersede the current options available for patients. Consequently, it will be very exciting to see how further mechanistic insight, particularly in the human pathological context, as well as the development of targeted treatment strategies facilitate our understanding of the satellite cell in this debilitating muscular disease.

Outstanding Questions.

What is the fate of dystrophic satellite cells that are unable to undergo proper asymmetric cell division? Elevated satellite cell numbers in dystrophic muscle suggest that dysfunctional satellite cells persist but are unable to participate in muscle regeneration. Satellite cells with defects in mitotic progression may default to a senescent state, thus recapitulating an aging phenotype.

Do dysfunctional satellite cells secrete factors that contribute to DMD disease progression? The contribution of dystrophic satellite cells to DMD may be two-fold; dystrophic satellite cells are unable to generate the myogenic progenitors required for muscle regeneration and may secrete factors that directly contribute to inflammation and fibrosis. The secretome of dystrophic satellite cells will need to be assessed.

Does the polarity deficit found in satellite cells extend to other tissues that contribute to DMD pathophysiology? Dystrophin is also expressed in cardiac muscle and the brain, which are affected in DMD. Cell polarity deficits in neurogenesis may explain the mental impairment observed in DMD patients.

Do similar mechanisms of satellite cell involvement in DMD extend to other muscular dystrophies? Mutations in genes encoding for components of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex are responsible for many of the muscular dystrophies. The role of these components in mediating cell polarity will need to be examined to determine if the polarity deficit in satellite cells is a common phenomenon underlying muscular dystrophies and neuromuscular disorders in general.

Can we restore polarity in satellite cells to treat DMD? The use of pharmacological approaches to inhibit centrosome amplification has been examined in cancer therapy. Exploitation of these strategies to restore cell polarity and stimulate endogenous satellite cell function in DMD should be explored.

Trends Box.

Dystrophic muscle stem cells (satellite cells) are intrinsically impaired and directly contribute to DMD progression in mdx mice, demonstrating that DMD is also a stem cell disease.

Satellite cells express high levels of dystrophin, which is expressed during cell division to mediate cell polarity. In mdx satellite cells, establishment of polarity is impaired resulting in the abrogation of asymmetric cell divisions, mitotic abnormalities, and inefficient generation of myogenic progenitors.

Recent advances in genome editing, myogenic cell reprogramming, and myogenic progenitor expansion protocols have important implications for genetic and muscle stem cell transplantation therapies.

Combinatorial approaches to restore endogenous satellite cell function with therapies that relieve fibrosis and inflammation associated with muscle degeneration may offer a potential cure for DMD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Morten Ritso for critical reading of the manuscript. N.C.C. is a recipient of the Centre for Neuromuscular Disease (CNMD) Scholarship in Translational Research Award from the University of Ottawa Brain and Mind Research Institute, and was supported by fellowships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Ontario Institute for Regenerative Medicine. F.P.C. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM)-Téléthon. These studies were carried out with support of grants to M.A.R. from the US National Institutes for Health (R01AR044031), the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-81288 and MOP-12080), the Stem Cell Network, the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, and the Canada Research Chair Program. M.A.R. holds a Canada Research Chair in Molecular genetics.

Glossary

- Apicobasal

the axis that extends from the apical to basal side of the cell or tissue

- Autophagy

a cellular pathway to degrade and recycle nutrients from intracellular organelles and proteins

- Cell polarity

the asymmetric spatial organization of cellular components within a cell

- Centrosome

the organelle from which microtubules are organized for formation of the mitotic spindle

- in situ proximity ligation assay

a highly sensitive fluorescent-based method to detect protein interactions or protein modifications (e.g. protein phosphorylation) in tissue or cells

- mdx

a mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) that arose from a spontaneous mutation generating a premature stop codon within exon 23 of the dystrophin gene. These mice exhibit robust muscle degeneration of the limb and diaphragm muscles and display a milder disease phenotype compared to human DMD patients

- Mitotic spindle

a cytoskeletal structure responsible for segregating chromosomes into two daughter cells during cell division

- Neuroblast

a neural stem cell that is able to undergo several rounds of mitosis to generate diverse type of neurons, which are postmitotic cells

- Neurocyte

any kind of differentiated postmitotic nerve cell

- Par complex

an evolutionarily conserved protein complex comprised of PAR3, PAR6 and aPKC that is essential for establishment of cell polarity

- Planar

the axis within the plane of the cell or tissue that is perpendicular to the apicobasal axis

- Planar cell polarity

the coordinated alignment of cellular components along the plane of the cell or tissue

- Satellite cells

adult stem cells of skeletal muscle

- Self-renewal

a fundamental property of stem cells to generate identical progeny either by symmetric or asymmetric cell divisions

- Senescence

a permanent state of cell cycle arrest

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Emery AE. Population frequencies of inherited neuromuscular diseases--a world survey. Neuromuscular disorders : NMD. 1991;1:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90039-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet (London, England) 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig M, et al. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell. 1988;53:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenig M, et al. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell. 1987;50:509–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahimov F, Kunkel LM. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying muscular dystrophy. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;201:499–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman EP, et al. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell KP, Kahl SD. Association of dystrophin and an integral membrane glycoprotein. Nature. 1989;338:259–262. doi: 10.1038/338259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ervasti JM, et al. Deficiency of a glycoprotein component of the dystrophin complex in dystrophic muscle. Nature. 1990;345:315–319. doi: 10.1038/345315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrof BJ, et al. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3710–3714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kharraz Y, et al. Understanding the process of fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:965631. doi: 10.1155/2014/965631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumont NA, et al. Dystrophin expression in muscle stem cells regulates their polarity and asymmetric division. Nat Med. 2015;21:1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/nm.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. The Journal of biophysical and biochemical cytology. 1961;9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Maltzahn J, et al. Pax7 is critical for the normal function of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307680110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepper C, et al. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3639–3646. doi: 10.1242/dev.067595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy MM, et al. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3625–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambasivan R, et al. Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3647–3656. doi: 10.1242/dev.067587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin H, et al. Satellite cells and the muscle stem cell niche. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:23–67. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huard J, et al. Dystrophin expression in myotubes formed by the fusion of normal and dystrophic myoblasts. Muscle & Nerve. 1991;14:178–182. doi: 10.1002/mus.880140213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miranda AF, et al. Immunocytochemical study of dystrophin in muscle cultures from patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and unaffected control patients. The American journal of pathology. 1988;132:410–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blau HM, et al. Defective myoblasts identified in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4856–4860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacco A, et al. Short telomeres and stem cell exhaustion model Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mdx/mTR mice. Cell. 2010;143:1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kottlors M, Kirschner J. Elevated satellite cell number in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell and tissue research. 2010;340:541–548. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0976-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bankole LC, et al. Fibre type-specific satellite cell content in two models of muscle disease. Histopathology. 2013;63:826–832. doi: 10.1111/his.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulfield G, et al. X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:1189–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang C, et al. Notch signaling deficiency underlies age-dependent depletion of satellite cells in muscular dystrophy. Disease models & mechanisms. 2014;7:997–1004. doi: 10.1242/dmm.015917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boldrin L, et al. Satellite cells from dystrophic muscle retain regenerative capacity. Stem Cell Research. 2015;14:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Megeney LA, et al. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1173–1183. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukada S, et al. Genetic background affects properties of satellite cells and mdx phenotypes. The American journal of pathology. 2010;176:2414–2424. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang NC, Rudnicki MA. Satellite cells: the architects of skeletal muscle. Current topics in developmental biology. 2014;107:161–181. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416022-4.00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuang S, et al. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell. 2007;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dewey EB, et al. Cell Fate Decision Making through Oriented Cell Division. J Dev Biol. 2015;3:129–157. doi: 10.3390/jdb3040129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knoblich JA. Asymmetric cell division: recent developments and their implications for tumour biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:849–860. doi: 10.1038/nrm3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirtz-Peitz F, et al. Linking cell cycle to asymmetric division: Aurora-A phosphorylates the Par complex to regulate Numb localization. Cell. 2008;135:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith CA, et al. aPKC-mediated phosphorylation regulates asymmetric membrane localization of the cell fate determinant Numb. EMBO J. 2007;26:468–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, et al. Polo inhibits progenitor self-renewal and regulates Numb asymmetry by phosphorylating Pon. Nature. 2007;449:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature06056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Couturier L, et al. Endocytosis by Numb breaks Notch symmetry at cytokinesis. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:131–139. doi: 10.1038/ncb2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benton R, St Johnston D. Drosophila PAR-1 and 14-3-3 inhibit Bazooka/PAR-3 to establish complementary cortical domains in polarized cells. Cell. 2003;115:691–704. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00938-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki A, et al. aPKC acts upstream of PAR-1b in both the establishment and maintenance of mammalian epithelial polarity. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schober M, et al. Bazooka recruits Inscuteable to orient asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature. 1999;402:548–551. doi: 10.1038/990135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siller KH, et al. The NuMA-related Mud protein binds Pins and regulates spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature cell biology. 2006;8:594–600. doi: 10.1038/ncb1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, et al. Aurora-A acts as a tumor suppressor and regulates self-renewal of Drosophila neuroblasts. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3453–3463. doi: 10.1101/gad.1487506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee CY, et al. Drosophila Aurora-A kinase inhibits neuroblast self-renewal by regulating aPKC/Numb cortical polarity and spindle orientation. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3464–3474. doi: 10.1101/gad.1489406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price FD, et al. Inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling stimulates adult satellite cell function. Nat Med. 2014;20:1174–1181. doi: 10.1038/nm.3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamashita K, et al. The 8th and 9th tandem spectrin-like repeats of utrophin cooperatively form a functional unit to interact with polarity-regulating kinase PAR-1b. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;391:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Troy A, et al. Coordination of satellite cell activation and self-renewal by Par-complex-dependent asymmetric activation of p38alpha/beta MAPK. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ono Y, et al. Muscle Stem Cell Fate Is Controlled by the Cell-Polarity Protein Scrib. Cell Reports. 2015;10:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomez-Lopez S, et al. Asymmetric cell division of stem and progenitor cells during homeostasis and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:575–597. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1386-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothenberg SM, et al. A genome-wide screen for microdeletions reveals disruption of polarity complex genes in diverse human cancers. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2158–2164. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCaffrey LM, et al. Loss of the Par3 polarity protein promotes breast tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nolan ME, et al. The polarity protein Par6 induces cell proliferation and is overexpressed in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8201–8209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cunliffe HE, et al. PAR6B is required for tight junction formation and activated PKCzeta localization in breast cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2012;2:478–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pece S, et al. Loss of negative regulation by Numb over Notch is relevant to human breast carcinogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:215–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Westhoff B, et al. Alterations of the Notch pathway in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22293–22298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907781106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito T, et al. Regulation of myeloid leukaemia by the cell-fate determinant Musashi. Nature. 2010;466:765–768. doi: 10.1038/nature09171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sen S, et al. Amplification/overexpression of a mitotic kinase gene in human bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1320–1329. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.17.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nogawa M, et al. Intravesical administration of small interfering RNA targeting PLK-1 successfully prevents the growth of bladder cancer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:978–985. doi: 10.1172/JCI23043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sen S, et al. A putative serine/threonine kinase encoding gene BTAK on chromosome 20q13 is amplified and overexpressed in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 1997;14:2195–2200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maire V, et al. Polo-like kinase 1: a potential therapeutic option in combination with conventional chemotherapy for the management of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:813–823. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bischoff JR, et al. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knecht R, et al. Prognostic significance of polo-like kinase (PLK) expression in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2794–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakakura C, et al. Tumour-amplified kinase BTAK is amplified and overexpressed in gastric cancers with possible involvement in aneuploid formation. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:824–831. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weichert W, et al. Expression patterns of polo-like kinase 1 in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolf G, et al. Prognostic significance of polo-like kinase (PLK) expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 1997;14:543–549. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanner MM, et al. Frequent amplification of chromosomal region 20q12-q13 in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1833–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takai N, et al. Expression of polo-like kinase in ovarian cancer is associated with histological grade and clinical stage. Cancer Lett. 2001;164:41–49. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li D, et al. Overexpression of oncogenic STK15/BTAK/Aurora A kinase in human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dietzmann K, et al. Increased human polo-like kinase-1 expression in gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2001;53:1–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1011808200978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fukasawa K. Centrosome amplification, chromosome instability and cancer development. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nam HJ, van Deursen JM. Cyclin B2 and p53 control proper timing of centrosome separation. Nature cell biology. 2014;16:538–549. doi: 10.1038/ncb2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gonczy P. Centrosomes and cancer: revisiting a long-standing relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:639–652. doi: 10.1038/nrc3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kramer A, et al. Centrosome clustering and chromosomal (in)stability: a matter of life and death. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marthiens V, et al. Centrosome amplification causes microcephaly. Nature cell biology. 2013;15:731–740. doi: 10.1038/ncb2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lara-Gonzalez P, et al. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R966–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basto R, et al. Centrosome amplification can initiate tumorigenesis in flies. Cell. 2008;133:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Y, et al. Dystrophin is a tumor suppressor in human cancers with myogenic programs. Nat Genet. 2014;46:601–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waite A, et al. The dystrophin-glycoprotein complex in brain development and disease. Trends in neurosciences. 2012;35:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Noatynska A, et al. Mitotic spindle (DIS)orientation and DISease: cause or consequence? J Cell Biol. 2012;199:1025–1035. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201209015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wynshaw-Boris A, et al. Lissencephaly: mechanistic insights from animal models and potential therapeutic strategies. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:823–830. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Annese T, et al. Isolation and characterization of neural stem cells from dystrophic mdx mouse. Exp Cell Res. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nico B, et al. Severe alterations of endothelial and glial cells in the blood-brain barrier of dystrophic mdx mice. Glia. 2003;42:235–251. doi: 10.1002/glia.10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saudou F, Humbert S. The Biology of Huntingtin. Neuron. 2016;89:910–926. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Elias S, et al. Huntingtin regulates mammary stem cell division and differentiation. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:491–506. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu G, et al. Planar cell polarity signaling pathway in congenital heart diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:589414. doi: 10.1155/2011/589414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Phillips HM, et al. Vangl2 acts via RhoA signaling to regulate polarized cell movements during development of the proximal outflow tract. Circ Res. 2005;96:292–299. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000154912.08695.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips HM, et al. Disruption of planar cell polarity signaling results in congenital heart defects and cardiomyopathy attributable to early cardiomyocyte disorganization. Circ Res. 2007;101:137–145. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Biressi S, et al. A Wnt-TGFbeta2 axis induces a fibrogenic program in muscle stem cells from dystrophic mice. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:267ra176. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kollu S, et al. The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Safeguards Genomic Integrity of Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:1061–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marumoto T, et al. Aurora-A - a guardian of poles. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:42–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]