Abstract

Understanding the human experience is no longer an outcome explored strictly by social and behavioral researchers. Increasingly, biomedical researchers are also including patient reported outcomes (PRO) in their clinical research studies due to calls for increased patient engagement in research but also healthcare. Collecting PROs in clinical research studies offers a lens into the patient’s unique perspective providing important information to industry sponsors and the FDA. Approximately 30% of trials include PROs as primary or secondary endpoints and a quarter of FDA new drug, device and biologic applications include PRO data to support labelling claims. In this paper PRO, represents any information obtained directly from the patient or their proxy, without interpretation by another individual to ascertain their health, evaluate symptoms or conditions and extends the reference of PRO, as defined by the FDA, to include other sources such as patient diaries.

Consumers and clinicians consistently report that PRO data are valued, and can aide when deciding between treatment options; therefore an integral part of clinical research. However, little guidance exists for clinical research professionals (CRPs) responsible for collecting PRO data on the best practices to ensure quality data collection so that an accurate assessment of the patient’s view is collected. Therefore the purpose of this work was to develop and validate a checklist to guide quality collection of PRO data. The checklist synthesizes best practices from published literature and expert opinions addressing practical and methodological challenges CRPs often encounter when collecting PRO data in research settings.

Keywords: Patient reported outcome, Self-reported data, Patient diary, Clinical trials, guidance, questionnaire

1. Introduction

Measurement of Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) offers researchers a unique lens into the patient’s perspective and has been increasingly valued by both consumers and clinicians [1]. PRO data is provided directly by the patient without interpretation by another individual (e.g. clinician) in order to ascertain their health, evaluate symptoms or a condition and is based on the U. S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) definition of a PRO [2–4]. When there are subtle differences between treatments, these data may provide the only evidence to suggest that one intervention is superior to another [5]. The inclusion of PRO measurement has been incorporated into the FDA’s process for approval of new drug, biologic, and device applications [4, 6]. The value of PROs is gaining momentum with changes to the Affordable Care Act prompting clinicians to elicit the patient’s perspective, and may be linked to Medicare reimbursements in the future [7].

While social and behavioral researchers have historically included PROs as primary and secondary endpoints in their research, their inclusion are relatively new for many biomedical researchers. One review reported that approximately 30% (26,337 of 96,736) of biomedical trials included PROs as primary or secondary study endpoints [8]. Another review evaluating FDA new drug, device and biologic applications submitted between 2000–2012, found that 23% included PRO data to support labelling claims, and of those 81% included PROs as primary endpoints and 27% as secondary endpoints [9]. Formal integration of PROs into protocols with specific objectives demonstrates a researcher’s commitment to quality PRO data collection [10] demonstrating that PROs are not merely “a fashionable add-on” but are imperative for clinical research [11 ] (p. 2). Despite increased use of PROs, less than 10% of protocols include specific instructions for the administration, collection and management of PRO measures and resultant data [12]. Research professionals who implement study procedures rely on the research protocol for guidance [13] which is often limited to the purpose and rationale for selecting a specific PRO measure [10, 14–16].

Based on the premise that the patient’s perspective is a critical element of clinical research, the administration and management of these unique data should be rigorous to provide an accurate account of the patient’s experience and avoid ‘missing-ness’ [17]. Specific guidelines to improve reporting of PRO data have been published [2, 18–22], and updates to U.S. and European regulatory guidance are continually reviewed and revised [23, 24]. Non-profit organizations also provide expertise on PRO selection, implementation and methodological issues [25–27]. However, no single resource currently exists to guide quality data collection for clinical research professionals (CRPs) [28]. Therefore the purpose of this work was to apply an evidenced-based process to develop and validate a practical resource (checklist) for CRPs to guide the quality collection of PRO data, as compared to a per-protocol resource. For this work PRO is used as a term that broadly refers to any PRO measure, including questionnaires, instruments, diaries, or a survey (a collection of questionnaires) and focuses on pencil-and-paper measures.

2. Methods

2.1 Project Initiation

Authors developed “how-to” instructions for CRPs that lacked experience with PRO data collection. In developing this informal resource it was realized that no comprehensive resource existed for CRPs. When reviewing the literature to validate the informal guidelines, the authors identified a gap in the published resources. It was determined that a comprehensive resource could have broader application and utility if developed. Although electronic collection of PRO data may resolve some of the methodological challenges CRPs encounter in paper PRO data collection, these systems are not universally used.

2.2 Literature Review

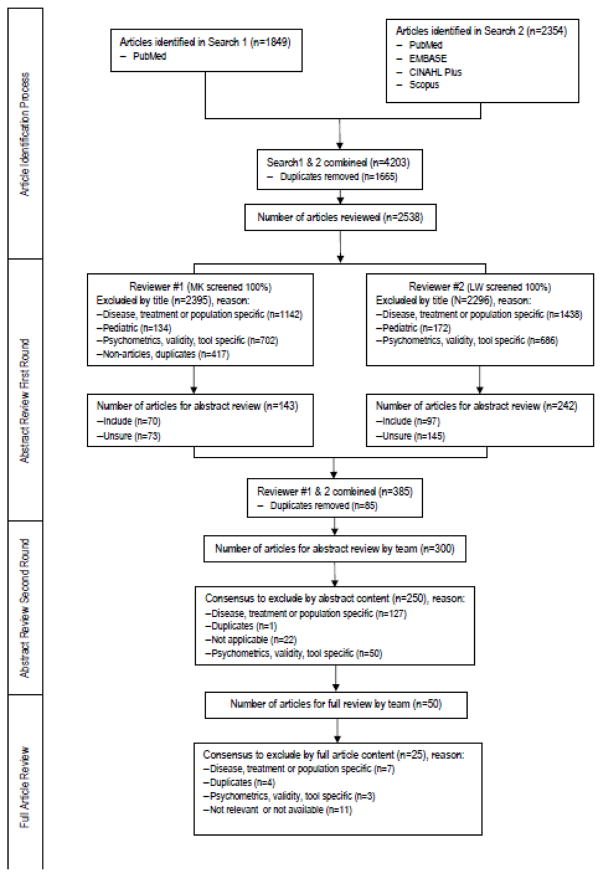

A systematic literature search was conducted using the following electronic databases: CINAHL, Embase, Scopus and PubMed. Each database was searched individually and with varying combinations of the following list of terms: practical guidance, guideline(s), method(s), patient reported outcome(s), quality of life, health related quality of life, outcomes assessment, self-assessment, questionnaires, diaries, clinical trials, clinical research, clinical study(ies), and randomized controlled trial(s). The search was limited to articles published from 1990 to October 2015, English only and adult populations. An Internet search for practical guidance as well as descendency and ancestry approaches were used to find additional articles specific to this work (Figure 1.0). Other gray literature was explored including unpublished work from within our organization and, as well as from professional nursing and research organizations to determine if formal guidance existed elsewhere.

Figure 1.

2.3 Expert Review

A draft checklist was developed, which combined evidence from the literature review with the initial informal resource. A group of experts were asked to review and provide feedback on the draft checklist. An ‘expert’ was defined based on their publication history and/or leadership experience in the use of PROs in clinical research settings. Five experts were identified and represented nursing and non-nursing, oncology and non-oncology clinical experts from a variety of roles such as research nurse study coordinator, scientist, and academic researcher. The checklist along with instructions and a reviewer feedback form were sent to each expert for an independent review. The workgroup collated the reviewers’ feedback. All experts responded and a final checklist was developed after thoroughly considering all suggestions and achieving consensus by the authors.

3. Results

3.1 Expert Reviewer Feedback

Five experts provided feedback on the initial checklist. Reviewers rated the checklist using a 5-point scale, (1=lowest and 5= highest score) on the relevance, ease of use, literature support and overall quality. Overall scores ranged from 4.25–5 and individual items ranged from 4.6–4.8 (Table 1). A separate open-ended question asked reviewers if the guidance was clear and comprehensive. Each shared that the checklist was clear and that it provided a concise yet comprehensive list of all major points.

Table 1.

Expert Reviewer Rating of PRO Checklist

| Average Item Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Relevance | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.8 |

| Ease of use | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.6 |

| Literature support | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.6 |

| Overall quality | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Average score by reviewer | 5 | 5 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 4.75 | |

Reviewers also provided feedback for individual items. This included identification of specific areas that could use additional clarification and recommendations for newer literature to support items included; note that six additional articles were recommended by expert reviewers or were published after the literature search was initially conducted. Three reviewers recommended clarifying terminology (i.e. PRO vs. PRO instrument vs. PRO data) and adding additional qualifiers to some items such as assessing environment and influencing factors, adding the timing to complete PRO, and how to avoid bias. One reviewer also recommended including checkboxes for ease of use by CRPs. Two reviewers recommended including information about electronic-PRO as an administration mode. However the authors concluded that literature was unique and beyond the scope of this work.

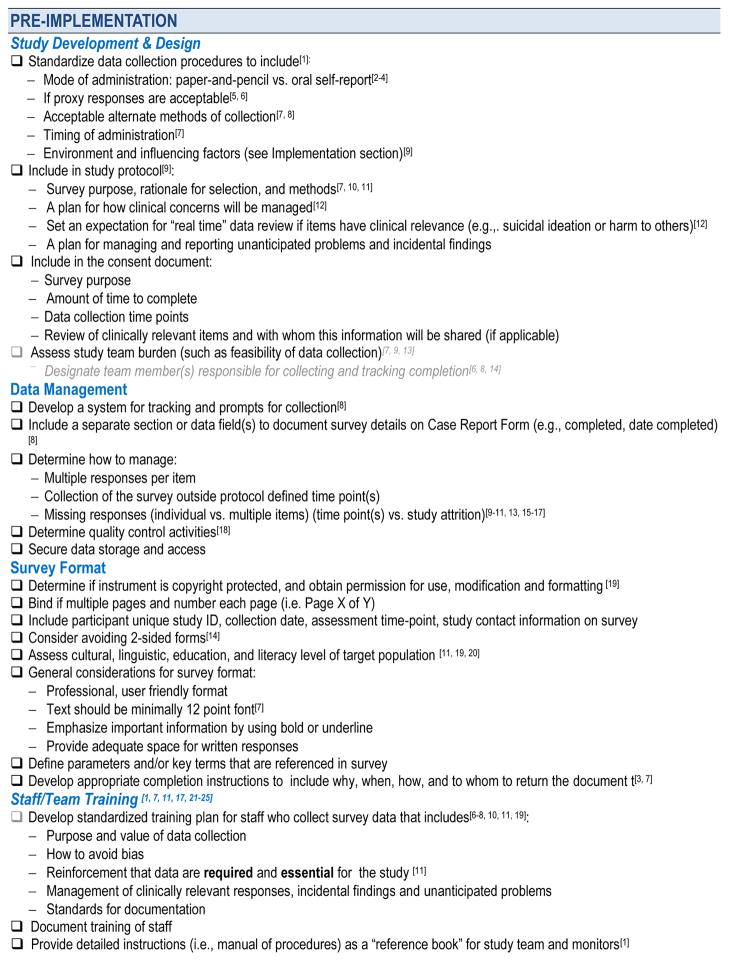

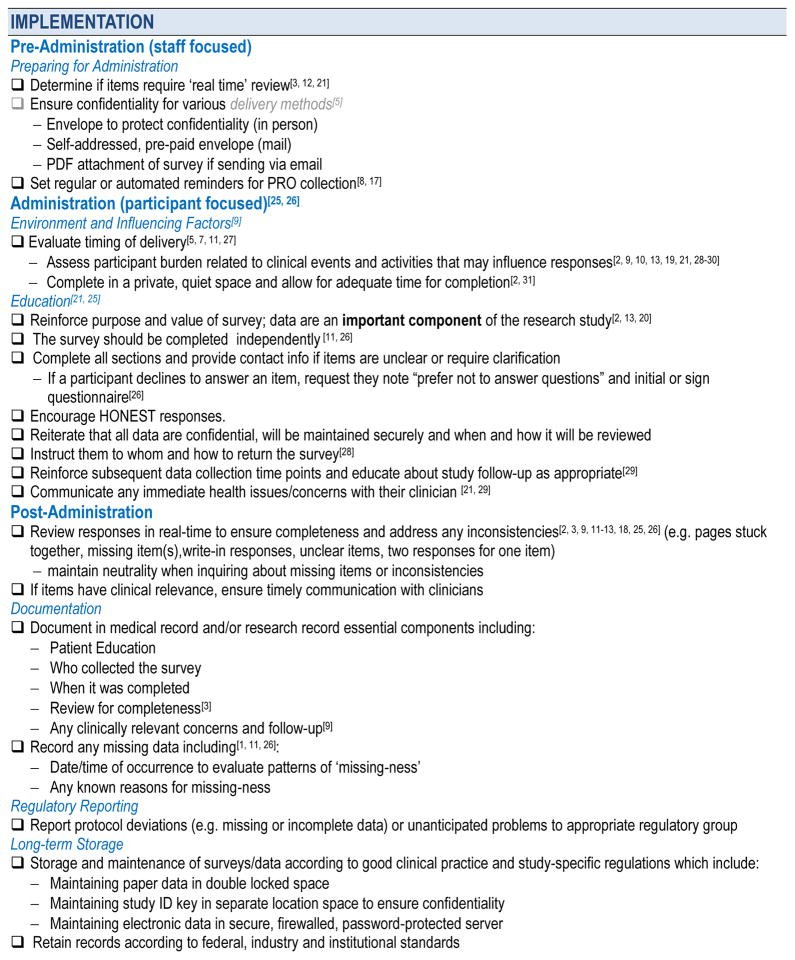

3.2 Overview of Checklist

The final evidence-based checklist (Figure 2.0) represents a combination of the recommendations from the reviewed published literature, expert opinion, and the authors’ experience to guide collection of PRO data by CRPs. The majority of articles reviewed were primarily expert guidance or individual center or researcher experience. Approximately 50% of the recommendations included in the checklist were not found in the literature but were conferred by experts or based on authors experience collecting PRO research data in clinical research settings.

Figure 2.

The checklist is divided into two distinct sections: ‘Pre-implementation’ and ‘Implementation’, each representing different phases of a protocol’s cycle. Pre-implementation includes front-end key considerations that occur during study development, such as design, data management, formatting and staff training. Though it is generally understood that the CRP may have limited input into the development of the study design, this information was included in the checklist to offer a comprehensive resource for CRP staff overseeing the administration of PRO data collection. The ‘Implementation’ section covers the period just prior to when the CRP administers the PRO survey, through administration, and post-administration; primarily focusing on guidance for PRO collection from the study participant. This part of the checklist includes specific actions for the CRPs involved in PRO data collection.

3.3 Pre-implementation

The majority of the work in this area has focused on study development and design. There are numerous sources that support the considerations in the front-end development of a research study that includes PRO data collection. While CRPs may not be routinely involved in the study design phase of protocol development, their expertise with a specific population, disease or setting may be valuable in recognizing factors that ultimately influence the study design and completion.

3.3.1 Study Development & Design

Standardizing Data Collection Procedures

When developing a study, standardizing data collection practices is strongly recommended [29]. Multiple articles made recommendations to standardize data collection practices such as: mode(s) of administration (self-reported vs. interview) [30–32], if proxy administrations will be permitted [33, 34], and if mixing methods (paper and electronic) of data collection are advisable [15, 21, 35]. The importance of timing the administration of PRO surveys is also well documented [15–17, 33]. The literature referenced avoiding PRO survey administrations that coincide with clinical events and activities such as disease staging, enrollment or removal from the study, sedating procedures, scans or other tests, and appointments which might influence the integrity of PRO data collection and participant responses [10, 11, 14, 28, 30, 31, 36–40]. In addition to clinical factors, understanding the impact of the amount of time to complete the PRO measures on participant burden is important.

Study Protocol

The study protocol should contain essential elements to guide PRO data collection [14]. This has been well described in the literature and includes the PRO purpose, rationale for outcome selection, and collection methods [10, 15, 16]. Some authors suggest that formal integration of PRO outcomes into research protocols as primary or secondary endpoints demonstrate a researcher’s commitment to incorporating the patient’s perspective into clinical research [10, 18]. Conversely, when PRO outcomes are secondary endpoints or are not formally integrated within the study design they may be de-prioritized by the research team and participants [42]. A significant body of literature exists that describes the selection of appropriate PRO measures that meet the disease’s or population’s characteristics [17].

When selecting the right measure [29] for the population, culture [36], language [37], disease process, trajectory, and side effects [14] are important factors. Research teams alike should be cognizant that PRO surveys cannot be modified without advance authorization from the developer of the measure [9] who will provide recommendations for use when requesting permission to use a specific PRO. Otherwise reliability and validity of the measure may be compromised.

While not well described in the literature it is recommended that research protocols with PRO outcomes include a plan for managing clinical concerns identified from the participant’s responses [43]. Experts recommended that a plan should take into account who, when and how the data will be reviewed once collected from the study participant, to meet all clinical and regulatory requirements based on the nature of the outcome assessed. Advance considerations for managing and reporting unanticipated problems and incidental findings are recommended. Based on the nature of the PRO, the research team should set an appropriate expectation related to time for data review, especially if items have clinical relevance (e.g. suicidal ideation or harm to others) [43].

Informed Consent Document

The Code of Federal Regulations, 21 CFR 50.20 describes the essential elements for informed consent, among which includes delineating specific research and study procedure details [44]. Although not clearly addressed in any of the published literature, the authors and the expert reviewers agreed that the study consent should include information that describes the purpose of the PRO measures, the amount of time required, and the times at which it will be administered. In addition, if the PRO measure involves ongoing collection, such as with a daily diary, details about when it will be reviewed and the expectation for completion should be described. If items are included that are clinically relevant or time-sensitive in nature, CRP’s should be able to describe the process of review and follow-up that each participant should expect. Including these elements in the consent form conveys to the participant the importance of the PRO measures to the overall research objective and meets the regulatory requirements for clearly communicating all procedures included with study participation.

Assessing the Impact on the Study Team

Understanding the impact of PRO data collection on research teams is essential and assures that data collection is feasible [14, 15, 36]. One study suggests the PRO completion could impact research staff but doesn’t provide specifics [41]. Several authors recommend designating a team member(s) for collecting and tracking PRO completion to standardize designation of roles and responsibilities [34, 35, 45]. Communication with clinicians or other research staff will help balance the burden between the study team with the participant.

3.3.2 Data Management

Missing data often arises due to either clinician or patient factors or a combination of both [40]. Missing data has been long touted as the most significant barrier of full integration of PRO surveys into clinical research [16, 29, 36, 40, 46]. Extensive guidance exists on how to avoid missing data as well as practical and statistical methods to handle missing data when it occurs [16, 29, 30, 40].

Advance planning when developing a research study should include a description of the PRO data collection and tracking systems to limit missing data, including prompts or alerts for staff that will be utilized [35, 46]. Tracking systems may be spreadsheets, participant specific calendars or a study calendar with automated reminders for PRO collection [35, 46]. One center described their multi-faceted approach to increase quality data collection that included appointing a PRO survey compliance officer, integration of PRO outcomes into all protocols, targeted messaging activities for staff and participants, and monthly progress reports to investigators and sites [48]. Another approach is to document collection details such as date completed on the case report form [35]. When detailed procedures with instructions and reminders are provided to staff responsible for collecting PRO data high completion rates (>90%) and minimal missing data have been reported [18]. Fayers and colleagues published textual examples with a checklist, specifically for protocol writers for consultation, when developing studies that include PRO data [49].

Advance consideration for how the research team will handle data irregularities is recommended before PRO implementation. To ensure quality data collection, continuous monitoring is required as with biomedical endpoints [11]. According to the literature reviewed, this should include decisions on how to handle multiple responses for an individual item(s), if PROs surveys are collected or returned outside the study design, missing responses, or when write-in responses are not clear [10, 14, 16, 36, 41, 46, 50]. Procedures should also describe who will contact the study participant and the timeframe permitted for follow-up to avoid recall bias. Determine quality control activities [19] in the protocol development phase, such as building in windows for data collection that anticipates both routine and unexpected patient and clinical factors that are typically experienced by the target population, is useful. Gralla and Thatcher emphasize that researchers should carefully consider the potential for subject attrition and what impact it might have on missing data since it introduces bias during analysis and interpretation of the findings of study endpoints [41].

The protocol should also describe how the PRO data (e.g. source documents) will be stored and who will have access to it. It is recommended to store and maintain source documents and data according to good clinical practice guidance [51] taking into account any agency or regulatory specific requirements. Specifics that are not well described include, but are not limited to, maintaining PROs surveys and any paper data in a double-locked or secured space, and separating the study ID key from PRO data, and any identifying information to ensure confidentiality. Electronically stored data should be maintained in a secure, firewalled, password-protected server with limited access. Retain PRO source documents and electronic databases that contain PRO data and records according to federal, industry and institutional standards.

3.3.3 Survey Format

The importance of PRO measures with a user-friendly format is documented [52]. However, prior to modifying an existing questionnaire the research team must determine if there is a copyright in place. If an individual questionnaire is copyright protected, obtain permission for use, modification and formatting [37]. If a PRO measure includes multiple pages, or multiple PRO measures are used, binding all pages into one document is recommended, including placement of page numbers on each page (i.e., Page X of Y). Some authors advise against using 2-sided forms to prevent inadvertent missing items when pages stick together [45]. Not well described is the value of including the participant unique study ID, collection date, assessment time-point, study contact information on the PRO measure to facilitate adequate identification for not only the study participant, but also the research team.

Considering the issue of copyright, the cultural, linguistic, education and literacy level of the population should be considered when formatting a PRO survey [16, 37, 53]. Additional considerations for PRO format might include a professional, user friendly format, with text no less than 12 point font [15]. Any important words, phrases, or information should be emphasized using bold or underlined font. Other considerations are defining parameters and/or key terms that are referenced in PRO and developing participant instructions that provide information about survey completion, which may include why, when, how, and to whom to return the document [31].

3.3.4 Staff and Research Team Training

Several sources recommend that a training plan should include detailed instructions on staff training, data management, quality control procedures and be available to all current and future study team members and monitors [11, 16, 28, 29, 42, 46, 52, 54, 55]. Recommendations specific to the CRP include advance training of study staff as a method to ensure success with PRO measure administration and data collection [9, 29, 56]. Essential components include the purpose and value of data collection, how to avoid bias (i.e., maintaining neutrality), reinforcement that data are required and essential for the study, and identify how clinically relevant responses (i.e. PRO alerts), incidental findings and unanticipated problems will be managed and documented [10, 15, 16, 34, 35, 37, 57]. If details of the staff training are too cumbersome for inclusion in the research protocol including details in a manual of procedures, which can be referenced in the research protocol, may be more appropriate.

3.4 Implementation

The recommendations made for the implementation phase often build on elements outlined in the pre-implementation phase. This phase involves the practical recommendations and actionable steps for CRPs involved in PRO data collection.

3.4.1 Pre-Administration (staff focused)

Preparing for PRO Administration

CRPs have several considerations prior to delivering a PRO document for completion. Prior to the administration, determine if any items will require ‘real time’ review because of clinical significance (i.e. PRO alerts) [28, 31, 43, 58]. CRPs can ensure success by providing adequate time for completion, ensuring that administration will not occur after-hours and that there is plenty of time for staff review. Because sensitive information may be included, confidentiality must be maintained during collection [33]. Experts recommend using an envelope that has a tamper proof seal, a pre-paid self-addressed envelope for mailing, or a PDF attachment if sending via email with a secure system for their return (e.g., fax or via secure email).

3.4.2 Administration, Participant Focused

Assessing Environment and Influencing Factors

Evaluating the environment is an essential for data collection. When CRPs meet with participants providing a private and quiet space, minimizing interruptions, and ensuring enough time for completion are known factors that enhance PRO completion [30, 59]. Multiple articles discuss the critical importance to evaluate the timing of delivery of PRO surveys by assessing participant burden related to clinical events and activities that may influence their responses [10, 14–17, 28, 30, 33, 36–40].

Educating Participants

Educating participants is considered an ongoing activity in clinical research [28, 55]. Beyond reviewing detailed instructions for the individual measure, participant education should include reinforcement of the purpose and value of the PRO survey [30, 36, 53], the importance of honest responses, the mode of administration, the importance of completing the items independently [16, 18], and that all sections should be completed. Contact information should be provided so that if items are unclear or require clarification the participant will know who to contact [38]. Also, reiterate that all PRO data are confidential, will be maintained securely, and when and how it will be reviewed by the research team. Participants should be reminded that any immediate health issues should be communicated to their clinician for appropriate follow-up [28, 55]. Psychological or physical symptoms may be actively monitored and require action based on regulatory requirements from an IRB or FDA [28, 39, 58]. If participants decline to answer an item, have them note “prefer not to answer questions” and initial item [18]. In addition to verbal instructions, provide written instructions that include to whom and how to return the documents as appropriate [38]. Educating about the study design including data collection time points and study follow-up should also be considered [39].

3.4.3 Post-Administration

According to the literature, when a document is completed it is recommended that a CRP review responses in real-time to ensure completeness and immediately address any inconsistencies [14, 16, 18, 19, 30, 31, 36, 43, 55]. This helps to avoid recall bias and manage missing data that might arise from pages sticking together, missing item(s), unclear write-in responses, or multiple responses. When inquiring about missing items or noted inconsistencies, CRPs should maintain neutrality to avoid introducing bias in the participant’s response. When items have clinical relevance, real-time review also helps to ensure timely communication with clinicians[58].

Documentation in the medical record and/or research record of all study related procedures is an expectation and best practice. This includes: patient education, who collected the documents, when it was completed and reviewed for completeness [31], any clinically relevant concerns, and subsequent follow-up that is needed [14]. Additionally, recording any missing data in the research record, case report form or medical record [16, 18, 29] helps to evaluate patterns and identify reasons for ‘missing-ness’ (e.g. same-day influences).

Regulatory Reporting

As with any other protocol specific procedure CRPs should report protocol deviations (e.g., missing or incomplete data) or unanticipated problems to the appropriate regulatory group based upon individual protocol, agency and/or federal requirements. Experts agree that although item level missing-ness is not routinely reported to the IRB, if subjects refuse to complete the measures, or a time-point is completely missed, the reasons should be documented, summarized and reported to the IRB as outlined in the protocol.

Long-term Storage

Regardless of the type of storage of PRO data (electronic vs. paper) experts recommend storing and maintaining documents and source data according to Good Clinical Practice guidance [51] and agency- and regulatory guidelines. This may include but not be limited to maintaining PRO surveys and any paper data in double locked space, separating the study ID key from PRO data, and any identifying information to ensure confidentiality. Electronically maintained PRO data should be stored in a secure, firewalled, password-protected server with limited access by those pre-determined on the research team requiring access. PRO source documents and electronic databases that contain PRO data should be retained according to federal, industry and institutional standards.

4. Discussion

Recommendations that guide PRO data collection for CRPs currently exist across numerous resources, which include U.S. and international guidance documents, published literature as well as recommendations by professional societies and other organizational websites. Previous work by Kyte et al. called for a comprehensive resource to ensure quality PRO data [28]. Good Clinical Practice guidelines generally lack practical recommendations for CRPs engaged in PRO data collection and FDA guidance may be overlooked as a resource by researchers involved in non-FDA regulated studies. The majority of the published evidence included expert guidance documents, and individual center or researcher experience. Therefore approximately 50% of the recommendations in this checklist were not described elsewhere but were conferred by experts or based on our team’s lived experience collecting PRO research data in clinical research settings.

A study based on interviews with research staff and key stakeholders identified three major areas where issues occur with PRO data collection: selection of measures, implementation methods, and data analysis and reporting [60]. Much of the published work has focused on the selection of measures and the data analysis and reporting elements when developing trials with PRO endpoints [22]. There is significantly less information available on implementation methods or specific practical tips for those collecting PRO data. While many implementation issues may be resolved by implementing electronic-PRO systems, they have not been widely adopted for PRO administration.

CRPs may continue to face issues when collecting PROs without comprehensive guidance. It has been suggested that having PRO champions embedded within the centers, working alongside biomedical researchers may increase the overall success, acceptance, and integration of PROs within research studies [42]. The absence of adequate guidance for PRO data collection by CRPs may affect data quality and create challenges for researchers when publishing and reporting results [28].

Although the effort to include the patient’s perspective may seem daunting, there are increasing accounts of a positive culture shift surrounding integration and value of these data by researchers [42]. This movement seems to be consistent with the FDA’s mandate for including the patient’s perspective in drug, biologic and device applications [3]. In 2004, Calvert and Freemantle discuss a shift in culture with drug researchers who increasingly incorporate PROs as primary and secondary endpoints in clinical trials [47]. In 2009, the FDA issued updated guidance that clarified how they evaluate PRO data included in new applications [4]. To some, these changes suggested a lack of confidence in the quality of PRO data or a realization that numerous methodological issues are encountered by researchers when including PRO data in their studies [36]. Others suggest changes in FDA guidance arose from concerns that PROs can be difficult to measure because they are multidimensional, subjective and ever-changing [11, 38]. Because PRO data collection does not always follow rigorous standards such as adequate blinding, or randomization procedures, the validity of the PRO data may be compromised [38]. Also, quantifying the clinical meaningfulness of PRO can be challenging with various methods available depending on the objectives of the study and application of the study findings once interpreted [61]. While changes to FDA’s guidance may have served as the initial impetus for increased PRO integration in clinical research studies, the majority of trials do not include PRO endpoints [8]. Nevertheless, the work in this area has increasingly shifted beyond PRO inclusion and more towards increasing the quality of PRO reporting.

Professional and non-profit organizations have also been working to standardize PRO usage, practices and reporting. This work builds on concurrent ISOQOL initiatives, which include two separate taskforces developing best practices for inclusion of PRO measures. The first taskforce, Protocol Checklist Development Team, is charged with creating a checklist or field guidance for protocol writers [62]. The second is the CONSORT-PRO Guidance Implementation Tools Team, which is working on tools for researchers to implement and promote the use of the CONSORT-PRO extension [62]. In addition, another group was convened to develop recommendations for standardized protocol items; an initiative known as the SPIRIT 2013 statement [63]. Additional resources are available through non-profit organizations that recognized a need for improvement in this PRO topic area. The aforementioned initiatives however focus on supporting protocol writers or researchers when disseminating results and are not specific to the CRP’s role in implementation and collection of PRO data.

4.1 Implications of findings

Guidance previously has not been readily available and expectedly CRPs have reported inconsistencies in practice [28]. Including a plan for the collection and management of PRO data, although considered a standard component for a clinical trial [63], is seldom included in research studies [12, 19]. Other issues to consider are that CRPs, who are often nurses, rely on policy and procedural documents to guide their practice, lack time for journal review, and may have trouble appraising the available evidence [13]. The majority of the paper PRO data collection issues may be resolved through the establishment and implementation of comprehensive evidence-based guidance for researchers and staff that collect PRO data. This 2-page checklist includes a comprehensive listing of practical considerations that aligns with specific phases of a research study lifecycle, and is available as a single source. This work fills an existing gap for those involved in primary source collection, often the CRP.

4.2 Limitations

There are several limitations that should be noted in regard to this work. Specifically, the checklist does not address issues related to the use of technology for the PRO data collection, storage and documentation. Additionally, this work was not a systematic review, the majority of articles included are primarily expert guidance, case reports, or were based on experiential knowledge from the expert reviewers and authors. Also, there may be some instructions to guide CRPs included in individual PRO instrument instructions or user manuals however they are largely unavailable in order to determine if additional recommendations could be relevant to this work.

4.3 Future work

Future work to support CRPs in the collection and management of PRO data should focus on validating the items included in the checklist to ensure its utility in practice. Another area which should be examined would be practical considerations for CRPs involved in electronic PRO data collection.

5. Conclusion

Improved data quality will result in the better understanding of the human experience. This better understanding will ultimately guide clinicians and consumers on the tailored treatment options, goals of the Precision Medicine Initiative [64]. Development of a comprehensive resource for PRO data collection that is overwhelmingly accepted as the gold standard by researchers, their staff, patients and clinicians will require more than a mere publication of the resource. Critical for the acceptance of a ‘gold standard’ will include gaining additional support and validation by additional PRO experts and leaders in the field and also adoption by professional organizations.

The ultimate goal of clinical research is to generate information that supports clinical decision-making leading to improved medical knowledge and enhanced treatment strategies. Researchers continue to struggle with PRO data collection in research studies. While PRO data may be collected from a variety of sources (e.g., patient or proxy) and methods (e.g., paper, interview, or electronic), this work is intended to highlight best practice for CRPs directly engaged in the collection of paper PRO measures. The time in research is ripe for a change that will enable the launch of a new and comprehensive resource to facilitate quality PRO data collection in clinical research settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Informationist Judith Welsh, NIH Library, for developing the database search strategies and performing the literature searches in support of this review. We also sincerely thank our expert reviewers Nancy Kline-Leidy, PhD, Sally Brown, RN, BSN, MGA, OCN®, CBCN, CCRP, Lisa Hansen, RN, MS, AOCN®, Melanie Calvert, PhD and Madeleine King, PhD for their willingness, time, thoughtful review and expert consultation. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Clinical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Leslie Wehrlen, Email: lwehrlen@nih.gov.

Mike Krumlauf, Email: krumlaum@cc.nih.gov.

Elizabeth Ness, Email: nesse@mail.nih.gov.

Damiana Maloof, Email: dmaloof@partners.org.

Margaret Bevans, Email: mbevans@cc.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Basch E, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1624–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patrick DL, et al. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1--eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Services, U.S.D.o.H.a.H; F.a.D. Administration, editor. Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gralla RJ. Quality-of-life considerations in patients with advanced lung cancer: effect of topotecan on symptom palliation and quality of life. Oncologist. 2004;9(Suppl 6):14–24. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-90006-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson JR, Temple R. Food and Drug Administration requirements for approval of new anticancer drugs. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69(10):1155–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Congress, t; U.S.G.P. Office, editor. Public Law 111–148. 2010. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vodicka E, et al. Inclusion of patient-reported outcome measures in registered clinical trials: Evidence from ClinicalTrials.gov (2007–2013) Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gnanasakthy A, et al. Potential of patient-reported outcomes as nonprimary endpoints in clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:83. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz PA, Gotay CC. Use of patient-reported outcomes in phase III cancer treatment trials: lessons learned and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5063–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olschewski M, et al. Quality of life assessment in clinical cancer research. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvert M, et al. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) assessment in clinical trials: a systematic review of guidance for trial protocol writers. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerrish K, Clayton J. Promoting evidence-based practice: an organizational approach. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12(2):114–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryant D, Fernandes N. Measuring patient outcomes: a primer. Injury. 2011;42(3):232–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipscomb JGC, Snyder C. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer Measures, Methods, and Applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvert MJ, Freemantle N. RESEARCH NOTE Use of health-related quality of life in prescribing research. Part 2: methodological considerations for the assessment of health-related quality of life in clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics. 2004;29(1):85–94. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-4727.2003.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braido F, et al. Specific recommendations for PROs and HRQoL assessment in allergic rhinitis and/or asthma: a GA(2)LEN taskforce position paper. Allergy. 2010;65(8):959–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osoba D. The Quality of Life Committee of the Clinical Trials Group of the National Cancer Institute of Canada: organization and functions. Qual Life Res. 1992;1(3):211–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00635620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyte DG, et al. Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) in Clinical Trials: Is ‘In-Trial’ Guidance Lacking? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick D. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. Value Health. 2013;16(4):455–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eremenco S, et al. PRO data collection in clinical trials using mixed modes: report of the ISPOR PRO mixed modes good research practices task force. Value Health. 2014;17(5):501–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvert M, et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309(8):814–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, F.a.D.A. Roadmap to Patient-Focused Outcome Measurement in Clinical Trials 2015. 2016 Mar 4; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/ucm370177.htm.

- 24.Agency, E.M. Draft Reflection Paper on the use of patient reported (PRO) measures in oncology studies. 2014. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute, C.P. Patient-Reported Outcome Consortium. 2016 Mar 03; Available from: http://c-path.org/programs/pro/

- 26.Policy, C.f.M.T. Transforming Clinical Research. 2016 Mar 03; Available from: http://www.cmtpnet.org/our-work/transforming-clinical-research/

- 27.Forum, N.Q. About Us. 2016 Mar 04; Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/story/About_Us.aspx.

- 28.Kyte D, et al. Inconsistencies in quality of life data collection in clinical trials: a potential source of bias? Interviews with research nurses and trialists. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo X, Cappelleri JC. A practical guide on incorporating and evaluating patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials. Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs. 2008;25(4):197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher A, et al. Quality of life measures in health care. II: Design, analysis, and interpretation. BMJ. 1992;305(6862):1145–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6862.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halyard MY. The use of real-time patient-reported outcomes and quality-of-life data in oncology clinical practice. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(5):561–70. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schipper H. Guidelines and caveats for quality of life measurement in clinical practice and research. Oncology (Williston Park) 1990;4(5):51–7. discussion 70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackowski D, Guyatt G. A guide to health measurement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(413):80–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000079771.06654.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gotay CC, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in cancer treatment protocols: research issues in protocol development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84(8):575–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella DF. Methods and problems in measuring quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00343916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hao Y. Patient-reported outcomes in support of oncology product labeling claims: regulatory context and challenges. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(4):407–20. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gnanasakthy A, DeMuro C, Boulton C. Integration of patient-reported outcomes in multiregional confirmatory clinical trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;35(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rock EP, et al. Challenges to use of health-related quality of life for Food and Drug Administration approval of anticancer products. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;37:27–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder CF, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–14. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiklund I. Assessment of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials: the example of health-related quality of life. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18(3):351–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gralla RJ, Thatcher N. Quality-of-life assessment in advanced lung cancer: considerations for evaluation in patients receiving chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2004;46(Suppl 2):S41–7. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(04)80040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruner DW, et al. Issues and challenges with integrating patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored clinical trials networks. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5051–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyte D, Draper H, Calvert M. Patient-reported outcome alerts: ethical and logistical considerations in clinical trials. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1229–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, in 21 CFR 50.20. 2012:.

- 45.Hopwood P, et al. Survey of the Administration of quality of life (QL) questionnaires in three multicentre randomised trials in cancer. The Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party the CHART Steering Committee. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lipscomb J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: taking stock, moving forward. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5133–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calvert MJ, Freemantle N. Use of health-related quality of life in prescribing research. Part 2: methodological considerations for the assessment of health-related quality of life in clinical trials. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2004;29(1):85–94. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-4727.2003.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Land SR, et al. Compliance with patient-reported outcomes in multicenter clinical trials: methodologic and practical approaches. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5113–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fayers PM. Applying item response theory and computer adaptive testing: the challenges for health outcomes assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl 1):187–94. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young T, Maher J. Collecting quality of life data in EORTC clinical trials--what happens in practice? Psychooncology. 1999;8(3):260–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199905/06)8:3<260::AID-PON383>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, F.a.D.A. Guidance for Industry, E6 Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance. Rockville, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder C. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer : Measures, Methods and Applications. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jahagirdar D, et al. Using patient reported outcome measures in health services: a qualitative study on including people with low literacy skills and learning disabilities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:431. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morita S, et al. Assessment and data analysis of health-related quality of life in clinical trials for gastric cancer treatments. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9(4):254–61. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basch E, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(34):4249–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atkinson TM, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a training workshop for the collection of patient-reported outcome (PRO) interview data by research support staff. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(1):33–7. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0427-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fayers PM, et al. Quality of life assessment in clinical trials--guidelines and a checklist for protocol writers: the U.K. Medical Research Council experience. MRC Cancer Trials Office. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(1):20–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kyte D, et al. Management of Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Alerts in Clinical Trials: A Cross Sectional Survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0144658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Testa MA, Nackley JF. Methods for quality-of-life studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:535–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Basch EM, et al. Development of a guidance for including patient-reported outcomes (PROS) in late-phase adult clinical trials of oncology drugs for comparative effectiveness research (CER) Value in Health. 2012;15(4):A226–A227. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG. Interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res. 2014;23(5):460–83. doi: 10.1177/0962280213476377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Research, I.S.f.Q.o.L. Committees: Best Practices for PROs in Randomized Clinical Trials. 2015 Oct 22; Available from: http://www.isoqol.org/about-isoqol/committees/best-practices-for-pros-in-randomized-clinical-trials.

- 63.Chan AW, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The White House, O.o.t.P.S. FACT SHEET: President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative. 2015. [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Luo X, Cappelleri JC. A practical guide on incorporating and evaluating patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials. Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs. 2008;25(4):197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher A, et al. Quality of life measures in health care. II: Design, analysis, and interpretation. BMJ. 1992;305(6862):1145–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6862.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halyard MY. The use of real-time patient-reported outcomes and quality-of-life data in oncology clinical practice. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(5):561–70. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schipper H. Guidelines and caveats for quality of life measurement in clinical practice and research. Oncology (Williston Park) 1990;4(5):51–7. discussion 70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackowski D, Guyatt G. A guide to health measurement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(413):80–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000079771.06654.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotay CC, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in cancer treatment protocols: research issues in protocol development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84(8):575–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipscomb JG, Carolyn C, Snyder Claire. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005. p. 662. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella DF. Methods and problems in measuring quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00343916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant D, Fernandes N. Measuring patient outcomes: a primer. Injury. 2011;42(3):232–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz PA, Gotay CC. Use of patient-reported outcomes in phase III cancer treatment trials: lessons learned and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5063–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvert MJ, Freemantle N. RESEARCH NOTE Use of health-related quality of life in prescribing research. Part 2: methodological considerations for the assessment of health-related quality of life in clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics. 2004;29(1):85–94. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-4727.2003.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyte D, Draper H, Calvert M. Patient-reported outcome alerts: ethical and logistical considerations in clinical trials. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1229–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao Y. Patient-reported outcomes in support of oncology product labeling claims: regulatory context and challenges. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(4):407–20. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopwood P, et al. Survey of the Administration of quality of life (QL) questionnaires in three multicentre randomised trials in cancer. The Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party the CHART Steering Committee. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young T, Maher J. Collecting quality of life data in EORTC clinical trials--what happens in practice? Psychooncology. 1999;8(3):260–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199905/06)8:3<260::AID-PON383>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gralla RJ, Thatcher N. Quality-of-life assessment in advanced lung cancer: considerations for evaluation in patients receiving chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2004;46(Suppl 2):S41–7. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(04)80040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipscomb J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: taking stock, moving forward. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5133–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kyte DG, et al. Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) in Clinical Trials: Is ‘In-Trial’ Guidance Lacking? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gnanasakthy A, DeMuro C, Boulton C. Integration of patient-reported outcomes in multiregional confirmatory clinical trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;35(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahagirdar D, et al. Using patient reported outcome measures in health services: a qualitative study on including people with low literacy skills and learning disabilities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:431. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyte D, et al. Inconsistencies in quality of life data collection in clinical trials: a potential source of bias? Interviews with research nurses and trialists. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita S, et al. Assessment and data analysis of health-related quality of life in clinical trials for gastric cancer treatments. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9(4):254–61. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olschewski M, et al. Quality of life assessment in clinical cancer research. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruner DW, et al. Issues and challenges with integrating patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored clinical trials networks. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5051–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basch E, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(34):4249–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osoba D. The Quality of Life Committee of the Clinical Trials Group of the National Cancer Institute of Canada: organization and functions. Qual Life Res. 1992;1(3):211–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00635620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braido F, et al. Specific recommendations for PROs and HRQoL assessment in allergic rhinitis and/or asthma: a GA(2)LEN taskforce position paper. Allergy. 2010;65(8):959–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rock EP, et al. Challenges to use of health-related quality of life for Food and Drug Administration approval of anticancer products. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;(37):27–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snyder CF, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–14. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiklund I. Assessment of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials: the example of health-related quality of life. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18(3):351–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Testa MA, Nackley JF. Methods for quality-of-life studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:535–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]