Abstract

Synthetic cannabinoids have been found in herbal incense products for the last several years. We report the rapid death of an individual that was certified as synthetic cannabinoid-associated. The autopsy blood specimen was extracted by a liquid–liquid extraction at pH 10.2 into a hexane–ethyl acetate mixture and analyzed by a generalized synthetic cannabinoid LC–MS-MS method. For this case report, we briefly describe the instrumental analysis and extraction methods for the detection of ADB-FUBINACA in postmortem blood, toxicological results for the postmortem blood specimen (ADB-FUBINACA, 7.3 ng/mL; THC, 1.1 ng/mL; THC-COOH, 4.7 ng/mL), case information and circumstances and pertinent findings at autopsy. The cause of death was certified as coronary arterial thrombosis in combination with synthetic cannabinoid use. Manner of death was accident.

Introduction

Synthetic cannabinoids are man-made substances that bind to the cannabinoid receptors 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2) in the human body. CB1 receptors are primarily located in the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) and are responsible for mediating the psychoactive effects of cannabis. The CB2 receptors are primarily located in the peripheral nervous system, as well as the spleen and immune system and are thought to be involved in pain perception mediation and immunosuppression (1). While delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive alkaloid found in cannabis, is considered a partial agonist of the CB1 and CB2 receptors, synthetic cannabinoids are considered to act as full agonists of the receptors.

Synthetic cannabinoid-containing products have been sold as herbal incense, herbal potpourri or smoking blends since approximately 2009 and have become popular as a cannabis alternative in the USA (2–5). The substances have been linked to many adverse effects including agitation, hypertension, tachycardia, acute kidney injury and fatality (6–14).

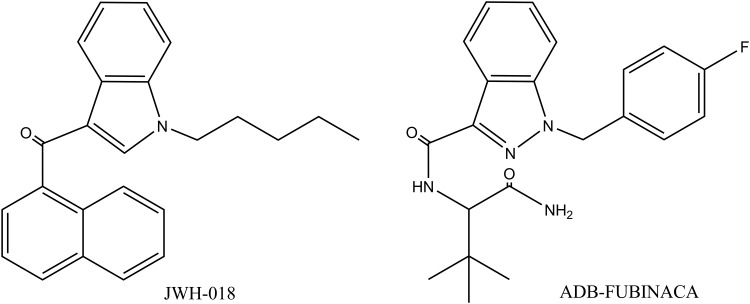

In 2015, we detected a new synthetic cannabinoid, N-[1-(amino-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide, otherwise known as ADB-FUBINACA, in our postmortem toxicology casework. The chemical structure of this new synthetic cannabinoid is shown in Figure 1. Herein we describe the detection of ADB-FUBINACA in whole blood specimens by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS) and report a fatal case associated with use of this compound via case history and circumstances, autopsy findings and postmortem toxicology results.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of JWH-018 and ADB-FUBINACA.

Materials and methods

During the routine autopsy procedures, a blood specimen was collected from the inferior vena cava in a 60-mL polypropylene bottle (with sodium fluoride and potassium oxalate added). Routine screening methods used in the toxicology laboratory included an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) screen for classical cannabinoids and opiates/opioids, a liquid chromatography and time of flight mass spectrometry screen (LC/ToF) for other abused drugs and therapeutic agents and a headspace gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) screen for volatile compounds. Synthetic cannabinoids were analyzed via a directed analysis by LC–MS-MS.

Reference standards for ADB-FUBINACA and the internal standard JWH-122-d9 were obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All other reagents and solvents including acetonitrile, ethyl acetate, formic acid, hexane, methanol, sodium bicarbonate and sodium carbonate were acquired from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Deionized (DI) water was obtained from the laboratory's water treatment system.

The organic extraction procedure and general LC–MS-MS parameters for the synthetic cannabinoid assay were previously published (12). In summary, a 500 μL aliquot of blood specimen was extracted at pH 10.2 into hexane–ethyl acetate (98:2). The organic supernatant was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen, and the residue was reconstituted in acetonitrile–DI water (50:50). LC–MS-MS was performed via a Waters (Milford, MA, USA) Acquity UltraPerformance® Liquid Chromatograph coupled to a Waters Tandem Quadrupole Detector (TQD). Ten microliters of specimen extract were injected onto a Waters UPLC® BEH C18 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 µm analytical column. General analytical method parameters and individualized settings for ADB-FUBINACA are detailed in Tables I and II.

Table I.

Chromatography

| Total time (min) | Flow rate (mL/min) | % A | % B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 0.500 | 58.0 | 42.0 |

| 0.30 | 0.500 | 58.0 | 42.0 |

| 5.60 | 0.500 | 34.0 | 66.0 |

| 8.00 | 0.500 | 24.0 | 76.0 |

| 8.50 | 0.500 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 8.51 | 0.500 | 58.0 | 42.0 |

| Mobile phases | A (0.1% formic acid in DI water); B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) | ||

| Retention time (minutes) | ADB-FUBINACA (2.3) JWH-122-d9 (7.2) |

||

Table II.

Mass Spectrometer Settings

| Analyte | Ion transition | Type | Dwell time (ms) | Cone voltage (V) | Collision energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADB-FUBINACA | 383.0 > 109.0 | Quantifying | 0.02 | 20 | 26 |

| ADB-FUBINACA | 383.0 > 253.0 | Qualifying | 0.02 | 20 | 44 |

| JWH-122-d9 | 365.3 > 169.1 | Internal standard | 0.02 | 44 | 29 |

| Capillary voltage (0.60 kV) | Extractor voltage (3 V) | Source temperature (140°C) | Desolvation temperature (450°C) | Desolvation gas flow (850 L/h) | Collision gas flow (0.30 mL/min) |

The analytical method for determination of ADB-FUBINACA in blood specimens was validated as a quantitative assay according to in-house validation standard operating procedures. Linearity, imprecision and accuracy, exogenous drug interferences, ion suppression and carryover were assessed. A summary of validation statistics is shown in Table III.

Table III.

Method Validation Results

| Parameter | ADB-FUBINACA |

|---|---|

| LOD | 0.1 ng/mL |

| LOQ | 0.2 ng/mL |

| Linearity | 0.2–10 ng/mL |

| Accuracy | |

| 1.5 ng/mL | |

| Intrarun | 84.6–106.2% |

| Interrun | 93.7% |

| 6 ng/mL | |

| Intrarun | 97.3–111.2% |

| Interrun | 101.9% |

| Imprecision | |

| 1.5 ng/mL | |

| Intrarun | 3.3–6.7% |

| Interrun | 11.4% |

| 6 ng/mL | |

| Intrarun | 4.8–6.3% |

| Interrun | 8.6% |

| Ion suppression | |

| 1.5 ng/mL | |

| Matrix effect | 1.15 (5.3% CV) |

| Response effect | 1.09 (7.3% CV) |

| 10 ng/mL | |

| Matrix effect | 1.02 (3.1% CV) |

| Response effect | 1.09 (2.2% CV) |

| 16 ng/mL | |

| Matrix effect | 0.99 (0.9% CV) |

| Response effect | 1.03 (1.2% CV) |

| Carryover | None detected at 100 ng/mL |

| Exogenous interferences | None detected |

Case report

While at home, a 41-year-old female smoked a synthetic cannabinoid product known as ‘Mojo’. Shortly after consumption of the product, she became violent and aggressive with her family. She was physically restrained by her children and eventually became unresponsive. She was declared dead by emergency personnel a short time thereafter.

Remarkable findings at autopsy included pulmonary edema, vascular congestion and thrombotic occlusion of the lumen of the left anterior descending coronary artery by hemorrhagic disruption of coronary arterial plaque as well as ischemia of the anterior left ventricular myocardium. The postmortem blood was subjected to a battery of generalized screening tests with reflexed confirmation analyses. The ELISA screen was presumptively positive for classical cannabinoids and negative for opiates/opioids. No substances were detected either on the LC/ToF comprehensive screen or the GC-FID volatiles assay. The presence of classical cannabinoids was confirmed via LC–MS-MS. THC and 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC-COOH) were quantified at 1.1 and 4.7 ng/mL, respectively. Directed LC–MS-MS for synthetic cannabinoids revealed the presence of ADB-FUBINACA (7.3 ng/mL). No other synthetic cannabinoids in the scope of analysis were detected.

The decedent's cause of death was certified as coronary arterial thrombosis in combination with synthetic cannabinoid use. Manner of death was accident.

Discussion

In 2009, the synthetic cannabinoid ADB-FUBINACA was developed by Pfizer and pursued as a potential therapeutic medication (15). In binding affinity (Ki) studies and activity in a GTPγS functional binding assay, Pfizer determined ADB-FUBINACA to have a Ki at CB1 equal to 0.36 nM and an EC50 equal to 0.98 nM. The substance was first detected in herbal incense products in Japan 4 years later (16). Other than binding affinity and functional activity at the CB1 receptor, very little is known about the pharmacology and toxicology of ADB-FUBINACA. Gatch and Forster studied a large number of new synthetic cannabinoid compounds, one of which was AB-FUBINACA (a close structural derivative of ADB-FUBINACA that was also covered in the 2009 Pfizer patent), in mice. They found that AB-FUBINACA fully substituted for the discriminative stimulus effects of THC, and they concluded that the compound would have cannabis-like psychoactive effects and would result in abuse liability (17). Knowing that ADB-FUBINACA binds to the CB1 receptor as a potent agonist and that ADB-FUBINACA differs from AB-FUBINACA in chemical structure by a replacement of an isopropyl moiety with a tert-butyl moiety, it is possible that ADB-FUBINACA may share a similar pharmacological profile with AB-FUBINACA and have similar cannabis-like psychoactive effects and potential liability for abuse. Metabolism and excretion of ADB-FUBINACA has been studied by Takayama et al. (18). They observed that ADB-FUBINACA metabolites are primarily formed via oxidation of the N-(1-amino-alkyl-1-oxybutan) moiety and excreted into the urine.

There exist no published reports regarding ADB-FUBINACA-related deaths. A related compound, ADB-PINACA, was associated with outbreaks of illness in Georgia and Colorado in 2013. Common adverse effects reported in the Georgia outbreaks included hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, acidosis, tachycardia, confusion/disorientation, aggression, unresponsiveness and seizures (19, 20). Common adverse effects in the Colorado incidents include tachycardia, somnolence, aggression and violence, agitation and confusion (21). No deaths were reported from either outbreak. In the case presented, the decedent became aggressive and violent, which were two common adverse effects reported in the ADB-PINACA-associated outbreak of illnesses in Georgia and Colorado. The decedent's demise in our case was rather rapid, and no other adverse effects were noted by witnesses or emergency personnel. At autopsy it was determined that the individual had a thrombolytic occlusion, which in isolation could result in death. However, given the documented temporal relationship of the use of the synthetic cannabinoid substance to the agitated and violent behavior and the rapid unexpected death, it was concluded that the mixture of coronary disease, thrombolytic occlusion and synthetic cannabinoid use was a lethal combination which blocked the artery's blood flow leading to dysrhythmia and death.

Over the last two years, the structurally similar synthetic cannabinoids AB-FUBINACA, AB-PINACA and ADB-PINACA were placed into Schedule I by the United States Federal Government (22, 23). ADB-FUBINACA is not currently scheduled by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), but may be considered a ‘controlled substance analog’ of AB-FUBINACA under the Analogue Enforcement Act.

Conclusion

Very little is known about the pharmacology and toxicology of newly emerged synthetic cannabinoids. There have been several reports published over the last few years that describe that adverse effects of the generalized synthetic cannabinoid family of substances, however, postmortem case reports still remain relatively rare. A LC–MS-MS method was used to detect ADB-FUBINACA in postmortem blood. Combining the circumstances surrounding the case including the temporal relationship of the use of the synthetic cannabinoid product, the toxicology findings and the autopsy findings, the cause of death was certified as synthetic cannabinoid related. As of the formation of this case report, this is the only death we have encountered involving ADB-FUBINACA. As synthetic cannabinoids continue to evolve and emerge, they will continue to be substances of extreme toxicological significance to clinical toxicologists, medical toxicologists and forensic toxicologists. In any death or poisoning in which synthetic cannabinoids are suspected to be involved, it is very important to analyze for said substances in the blood (or tissues) of the affected individual.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the chemists and technicians in the Forensic Business Unit and Research and Development group at AIT Laboratories.

References

- 1.Mechoulam R., Parker L.A. (2013) The endocannabinoid system and the brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 21–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penn H.J., Langman L.J., Unold D., Shields J., Nichols J.H. (2011) Detection of synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products. Clinical Biochemistry, 44, 1163–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logan B.K., Reinhold L.E., Xu A., Diamond F.X. (2012) Identification of synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense blends in the United States. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 57, 1168–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanks K.G., Dahn T., Behonick G., Terrell A. (2012) Analysis of first and second generation legal highs for synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic stimulants by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and time of flight mass spectrometry. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 36, 360–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanks K.G., Behonick G.S., Dahn T., Terrell A. (2013) Identification of novel third-generation synthetic cannabinoids in products by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and time of flight mass spectrometry. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 37, 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tofighi B., Lee J.D. (2012) Internet highs—seizures after consumption of synthetic cannabinoids purchased online. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 6, 240–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young A.C., Schwarz E., Medina G., Obafemi A., Feng S.Y., Kane C. et al. (2011) Cardiotoxicity associated with the synthetic cannabinoid, K9, with laboratory confirmation. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 30, 1320.e5–1320.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapoint J., James L.P., Moran C.L., Nelson L.S., Hoffman R.S., Moran J.H. (2011) Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clinical Toxicology, 49, 760–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornton S.L., Wood C., Friesen M.W., Gerona R.R. (2013) Synthetic cannabinoid use associated with acute kidney injury. Clinical Toxicology, 51, 189–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013) Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurney S.M.R., Scott K.S., Kacinko S.L., Presley B.C., Logan B.K. (2014) Pharmacology, toxicology, and adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoid drugs. Forensic Science Review, 26, 53–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behonick G., Shanks K.G., Firchau D.J., Mathur G., Lynch C.F., Nashelsky M. et al. (2014) Four postmortem case reports with quantitative detection of the synthetic cannabinoid, 5F-PB-22. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 38, 559–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasegawa K., Wurita A., Minakata K., Gonmori K., Nozawa H., Yamagishi I. et al. (2015) Postmortem distribution of AB-CHMINACA, 5-fluoro-AMB, and diphenidine in body fluids and solid tissues in a fatal poisoning case: usefulness of adipose tissue for detection of the drugs in unchanged forms. Forensic Toxicology, 33, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanks K.G., Winston D., Heidingsfelder J., Behonick G. (2015) Case reports of synthetic cannabinoid XLR-11 associated fatalities. Forensic Science International, 252, e6–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WO/2009/106982—Indazole Derivatives, Pfizer, Inc., 2/26/2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchiyama N., Matsuda S., Kawamura M., Kikura-Hanajiri R., Goda Y. (2013) Two new cannabimimetic quinolinyl carboxylates, QUPIC and QUCHIC, two new cannabimimetic carboxamide derivatives, ADB-FUBINACA and ADBICA, and five synthetic cannabinoids detected with a thiophene derivative α-PVT and an opioid receptor agonist AH-7921 identified in illegal products. Forensic Toxicology, 31, 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatch M.B., Forster M.J. (2015) Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-like effects of novel synthetic cannabinoids found on the gray market. Behavioural Pharmacology, 26, 460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takayama T., Suzuki M., Todoroki K., Inoue K., Min J.Z., Kikura-Hanajiri R. et al. (2014) UPLC/ESI-MS/MS-based determination of metabolism of several new illicit drugs, ADB-FUBINACA, AB-FUBINACA, AB-PINACA, QUPIC, 5F-QUPIC, and α-PVT, by human liver microsome. Biomedical Chromatography, 28, 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013) Notes from the field: severe illness associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—Brunswick, Georgia, 2013. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz M.D., Trecki J., Edison L.A., Stekc A.R., Arnold J.K., Gerona R.R. (2015) A common source outbreak of severe delirium associated with exposure to the novel synthetic cannabinoid ADB-PINACA. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 48, 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013) Notes from the field: severe illness associated with reported use of synthetic marijuana—Colorado, August–September 2013. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 1016–1017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drug Enforcement Administration. (2014) Schedules of controlled substances: temporary placement of four synthetic cannabinoids into Schedule I. Final order. Federal Register, 79, 7577–7582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drug Enforcement Administration. (2015) Schedules of controlled substances: temporary placement of three synthetic cannabinoids into Schedule I. Final order. Federal Register, 80, 5042–5047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]