Abstract

‘White oaks’—one of the main groups of the genus Quercus L.—are represented in western Eurasia by the ‘roburoid oaks’, a deciduous and closely related genetic group that should have an Arcto-Tertiary origin under temperate-nemoral climates. Nowadays, roburoid oak species such as Quercus robur L. are still present in these temperate climates in Europe, but others are also present in southern Europe under Mediterranean-type climates, such as Quercus faginea Lam. We hypothesize the existence of a coordinated functional response at the whole-shoot scale in Q. faginea under Mediterranean conditions to adapt to more xeric habitats. The results reveal a clear morphological and physiological segregation between Q. robur and Q. faginea, which constitute two very contrasting functional types in response to climate dryness. The most outstanding divergence between the two species is the reduction in transpiring area in Q. faginea, which is the main trait imposed by the water deficit in Mediterranean-type climates. The reduction in leaf area ratio in Q. faginea should have a negative effect on carbon gain that is partially counteracted by a higher inherent photosynthetic ability of Q. faginea when compared with Q. robur, as a consequence of higher mesophyll conductance, higher maximum velocity of carboxylation and much higher stomatal conductance (gs). The extremely high gs of Q. faginea counteracts the expected reduction in gs imposed by the stomatal sensitivity to vapor pressure deficit, allowing this species to diminish water losses maintaining high net CO2 assimilation values along the vegetative period under nonlimiting soil water potential values. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that Q. faginea can be regarded as an example of adaptation of a deciduous oak to Mediterranean-type climates.

Keywords: leaf area, roburoid oaks, stomatal conductance, vapor pressure deficit

Introduction

The genus Quercus L. (Fagaceae) comprises ∼400 tree and shrub species distributed among contrasting phytoclimates in the Northern Hemisphere, from temperate and subtropical deciduous forests to Mediterranean evergreen woodlands (Manos et al. 1999, Kremer et al. 2012). Although the successive infrageneric classifications of Quercus have undergone changes, all of them recognized the same major groups (see Denk and Grimm 2010 and references therein). One of the main groups is the so-called ‘Group Quercus’ or ‘white oaks’ (Denk and Grimm 2009), which is represented in western Eurasia by the so-called ‘roburoid oaks’ (Denk and Grimm 2010). The roburoid oaks that should have their origin in Arcto-Tertiary lineages during the Early Tertiary (Axelrod 1983, Kovar-Eder et al. 1996) are a quite coherent group of species with a high degree of genetic similarity (Olalde et al. 2002, Denk and Grimm 2010). Nowadays, one of the greatest representative roburoid oak species widely distributed along a temperate-nemoral climate is Quercus robur L., which is considered a meso-hygrophilous species (Piedallu et al. 2013) distributed in Europe from Spain to southern Scandinavia and from Ireland to eastern Europe (Ducousso and Bordacs 2004).

Nevertheless, the roburoid oaks are not exclusive of the temperate climates, but they are also present in southern Europe under Mediterranean-type climates (Corcuera et al. 2004, Himrane et al. 2004, Sánchez de Dios et al. 2009), which evidences the ability to survive in more xeric habitats (Kvacek and Walther 1989, Barrón et al. 2010). This may be the case of Quercus faginea Lam., for which the first fossil records, found in the south of France, coincide with the development of the Mediterranean seasonality during the Pliocene (Roiron 1983, Barrón et al. 2010).

Quercus faginea is the most abundant and widely distributed white oak in the Iberian Peninsula (Olalde et al. 2002). Some previous studies that have dealt with the resistance to drought of this species are mainly based on the comparison with other Mediterranean oak species, such as the evergreen Quercus ilex (Corcuera et al. 2002, Mediavilla and Escudero 2003). This comparison makes sense in terms of forest composition and vegetation dynamic in most continental Mediterranean areas of the Iberian Peninsula (Mediavilla and Escudero 2004), where Q. faginea and Q. ilex co-occur. These congeneric species constitute two examples of contrasting leaf habit, which itself represents quite different functional strategies (Kikuzawa 1995). In this sense, it has been proposed that the evergreen condition of Q. ilex would allow this species to assimilate carbon throughout a longer time period (Acherar and Rambal 1992, Ogaya and Peñuelas 2007, van Ommen Kloeke et al. 2012), which was empirically confirmed in cold Mediterranean areas (Corcuera et al. 2005a). On the contrary, the leaf life span of the deciduous Q. faginea limits the photosynthetic activity to a shorter period, implying the need for higher rates of carbon gain under favorable conditions (van Ommen Kloeke et al. 2012).

However, the importance in the Mediterranean forest landscape of the Iberian Peninsula and north of Africa of such deciduous Mediterranean oaks, such as Q. faginea and other congeneric species (Olalde et al. 2002, Benito Garzón et al. 2007, Sánchez de Dios et al. 2009), indicates that this leaf habit performs adequately under the limiting climatic conditions of Mediterranean areas. Therefore, some roburoid oaks, such as Q. faginea, must have developed functional strategies to adapt to the summer drought conditions, withstanding both edaphic and atmospheric water stresses.

In order to evaluate the physiological traits that Q. faginea shows for coping with the Mediterranean aridity, we established an interspecific comparison with Q. robur, other roburoid deciduous oak from temperate-nemoral climates. We hypothesize the existence of a coordinated functional response at the whole-shoot scale in Q. faginea under Mediterranean conditions. In this sense, the specific objectives of this study are (i) to analyze the morphological, anatomical, hydraulic, photosynthetic and biochemical traits of Q. faginea and (ii) to compare them with those from Q. robur, a temperate white oak genetically closely related but occurring under contrasting ecological and climatic conditions (Olalde et al. 2002, Himrane et al. 2004).

Materials and methods

Plant material and experimental conditions

Seeds from Q. robur L. (‘Galicia’ provenance, 42°34′N, 8°33′W, 300 m above sea level, Spain) and Q. faginea Lam. (‘Alcarria-Serranía de Cuenca’ provenance, 40°19′N, 2°15′W, 950 m above sea level, Spain) were sown and cultivated in 2009 under the same conditions (mixture of 80% substrate and 20% perlite in 500 ml containers) inside a transparent greenhouse of alveolar polycarbonate (CITA de Aragón, Zaragoza, Spain) that allowed passing 90% of photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD; ∼1500 mmol photons m2 s−1 at midday, during the experiments) and was equipped with an evaporative cooling system, set for keeping the air temperature inside the greenhouse below 30 °C, while air vapor pressure deficit (VPD) was ∼1 kPa through the experiments. Such environmental conditions are close to those recorded during the early growing season (May–June) for both species (Figure 1). Periodical surveys (twice a week) yielded no differences in the time of leaf unfolding between both species when cultivated under the same conditions (data not shown). Jato et al. (2002) also reported the same date for leaf unfolding in co-occurring populations of both species in northwestern Spain. After the first growth cycle, the seedlings were transplanted to containers of 25 l. All plants were irrigated every 2 days. Measurements were performed at the end of June 2012 in fully matured leaves of 4-year-old seedlings for both species.

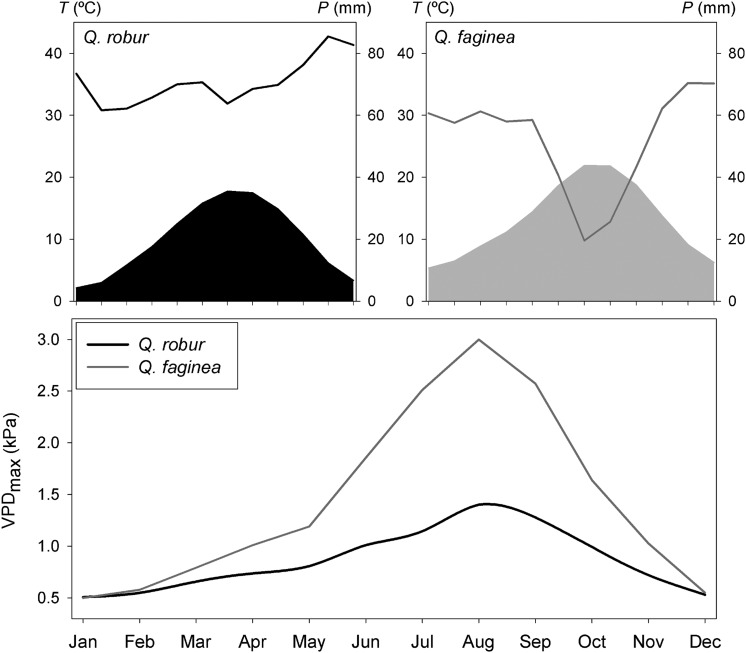

Figure 1.

Ombrothermic diagrams showing temperature (T, filled areas) and precipitation (P, lines) (upper panels) and VPDmax (lower panel) for the distribution ranges of Q. robur and Q. faginea.

The distribution ranges of each species have contrasting climatic conditions. Quercus robur occurs in sites where annual and summer precipitation (P and Ps, respectively) are higher than in the sites where Q. faginea occurs (Table 1). The mean annual and summer temperatures (T and Ts, respectively) are higher for the sites where Q. faginea occurs (Table 1). As a consequence, the Martonne aridity index [MAI = P/(T + 10)] and the Gaussen index (the number of months in which P < 2T, where P is the monthly precipitation in mm and T is the monthly mean temperature in °C) are also higher for the sites where Q. faginea occurs (Table 1, Figure 1). Climatic information was obtained from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org/) using 70 geographic points throughout the distribution range of Q. robur and Q. faginea, respectively. Moreover, VPD (kPa) was calculated using the data obtained from WeatherSpark database (http://weatherspark.com/) for six locations of Q. robur and Q. faginea, respectively. The maximum daily VPD (VPDmax, kPa) is much higher for the sites where Q. faginea occurs, especially during summer (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Mean climatic characteristics for the distribution ranges of Q. robur and Q. faginea: mean annual and summer temperature (T and Ts), total annual and summer precipitation (P and Ps), MAI and Gaussen index. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

| Species | T (°C) | Ts (°C) | P (mm) | Ps (mm) | MAI | Gaussen index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. robur | 9.9 ± 0.3a | 17.0 ± 0.2a | 850 ± 27a | 206 ± 9a | 43 ± 2a | 0 ± 0a |

| Q. faginea | 13.0 ± 0.3b | 20.8 ± 0.3b | 628 ± 15b | 86 ± 6b | 28 ± 1b | 2.6 ± 0.2b |

Morphological variables

Leaf area and leaf mass area (LMA) were measured in 30 mature leaves sampled from 10 individuals per species (i.e., three leaves were randomly taken from each individual). Leaf area was measured by digitalizing the leaves and using the ImageJ image analysis software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). Leaves were then oven-dried at 70 °C for 3 days to determine their dry weight. The LMA was calculated as the ratio of the foliage dry weight to foliage area and was used as an estimator of sclerophylly (Corcuera et al. 2002). Major vein density (MVD) was determined in another set of 10 mature leaves per species following the method described in Scoffoni et al. (2011) with some modifications. Leaves were chemically cleared with 5% NaOH in aqueous solution, washed with bleach solution, dehydrated in an ethanol dilution series (70, 90, 95 and 100%) and stained with safranin. Then, leaves were scanned at 1200 d.p.i. resolution, and the leaf area and lengths of first-, second- and third-order veins were measured using the ImageJ software. Vein densities for each order were calculated as the vein length/leaf area ratio (LAR). The MVD was then obtained as the sum of the first-, second- and third-order vein densities. Finally, the LAR was calculated in 10 current-year shoots per species by dividing the total leaf area per shoot (measured as described above) by the dry weight of the shoot.

Stem hydraulic conductivity

The hydraulic conductivity (Kh, kg m s−1 MPa−1) was determined in current-year stem segments of Q. robur and Q. faginea. Three stem segments (3–5 cm long and >1 mm in diameter) per branch were cut under water from 10 south-exposed branches per species. The measurement pressure was set to 4 kPa. The flow rate was determined with a PC-connected balance (Sartorius BP221S, 0.1 mg precision, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) by recording the change in weight every 10 s and fitting linear regressions over 200-s intervals. The conductivity measurements were carried out with distilled, filtered (0.22 μm) and degassed water containing 0.005% (volume/volume) Micropur (Katadyn Products, Wallisellen, Switzerland) to prevent microbial growth (Mayr et al. 2006). No native embolism was detected in the segments, as reflected by the comparison of the flow rates before and after applying short perfusions at 0.15 MPa for 60–90 s. The same stem segments were measured in length, diameter without bark and total leaf surface area supplied, to compute the main hydraulic architecture parameters, namely specific conductivity (Ks, kg m−1 s−1 MPa−1) as the hydraulic conductivity on a sapwood area basis, and leaf-specific conductivity (LSC, kg m−1 s−1 MPa−1) as hydraulic conductivity on a leaf area basis.

Leaf hydraulic conductance

Leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf, mmol m−2 s−1 MPa−1) for Q. robur and Q. faginea was calculated following the methodology described by Brodribb et al. (2005). Six sun-exposed branches from six plants per species were collected at 07:00–08:00 h (solar time), minimizing the possibility for midday Kleaf depression (Brodribb and Holbrook 2004). The branches were enclosed in sealed plastic bags to prevent water loss and stored in the dark for a period of at least 1 h until stomatal closure so that all leaves from the same branch could reach the same water potential. It is assumed that this is the water potential of the leaves prior to rehydration (Ψ0). Once this value was obtained, one leaf per branch was cut under water to prevent air entry and allowed to take up water for 30–60 s. The water potential after rehydration was subsequently obtained (Ψf). The Kleaf was calculated according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where Cl (mol MPa−1 m−2) is the leaf capacitance for each species. Cl was calculated as the initial slope of the pressure–volume relationships, normalized by the leaf area (Brodribb et al. 2005). Pressure–volume relationships for Q. robur and Q. faginea were determined in six leaves per species, following the free-transpiration method described in previous studies (Vilagrosa et al. 2003).

Leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

Leaf gas exchange parameters were determined simultaneously with measurements of chlorophyll fluorescence using an open gas exchange system (CIRAS-2, PP-Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) fitted with an automatic universal leaf cuvette (PLC6-U, PP-Systems) with an FMS II portable pulse amplitude modulated fluorometer (Hansatech Instruments Ltd, Norfolk, UK). Six CO2 response curves were obtained from Q. robur and Q. faginea. In light-adapted mature leaves, photosynthesis measurements started at a CO2 concentration surrounding the shoot (Ca) of 400 μmol mol−1 and a saturating PPFD of 1500 μmol m−2 s−1. Leaf temperature and VPD were maintained at 25 °C and 1.25 kPa, respectively, during measurements. Once a steady-state gas exchange rate was reached under these conditions (usually 30 min after clamping the leaf), net assimilation rate (AN), transpiration (E), stomatal conductance (gs) and the effective quantum yield of PSII were estimated. Thereafter, Ca was decreased stepwise down to 50 μmol mol−1. Upon completion of measurements at low Ca, Ca was increased again to 400 μmol mol−1 to restore the original value of AN. Then, Ca was increased stepwise to 1800 μmol mol−1. Leakage of CO2 in and out of the cuvette was determined for the same range of CO2 concentrations with a photosynthetically inactive leaf enclosed (obtained by heating the leaf until no variable chlorophyll fluorescence was observed) and used to correct measured leaf fluxes (Flexas et al. 2007a).

The effective photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (ΦPSII) was measured simultaneously with AN and gs. For ΦPSII, the steady-state fluorescence (FS) and the maximum fluorescence during a light-saturating pulse of ∼8000 μmol m−2 s−1 were estimated, and ΦPSII was calculated as following the procedures of Genty et al. (1989). The photosynthetic electron transport rate (Jflu) was then calculated according to Krall and Edwards (1992), multiplying ΦPSII by PPFD and by α (a term that includes the product of leaf absorptance and the partitioning of absorbed quanta between photosystems I and II). α was previously determined for each species as the slope of the relationship between ΦPSII and (i.e., the quantum efficiency of CO2 fixation) obtained by varying light intensity under nonphotorespiratory conditions in an atmosphere containing <1% O2 (Valentini et al. 1995). Five light curves from Q. robur and Q. faginea were measured to determine α.

Estimation of mesophyll conductance by gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence

Mesophyll conductance (gm) was estimated according to the method of Harley et al. (1992), as follows:

| (2) |

where AN and the substomatal CO2 concentration (Ci) were taken from gas exchange measurements at saturating light, whereas Γ* (the chloroplastic CO2 photocompensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration) and RL (the respiration rate in the light) were estimated for each species according to the Laisk (1977) method, following the methodology described in Flexas et al. (2007b). The values of gm obtained were used to convert AN–Ci into AN–Cc curves (where Cc is the chloroplastic CO2 concentration) using the equation Cc = Ci − AN/gm. The maximum carboxylation and Jflu capacities (Vc,max and Jmax, respectively) were calculated from the AN–Cc curves, using the Rubisco kinetic constants and their temperature dependence described by Bernacchi et al. (2002). The Farquhar model was fitted to the data by applying iterative curve fitting (minimum least-square difference) using the Solver tool of Microsoft Excel.

Anatomical measurements

After the gas exchange measurements, transverse slices of 1 × 1 mm were cut between the main veins from the same leaves for anatomical measurements. Leaf material was quickly fixed under vacuum with 2% p-formaldehyde (2%) and glutaraldehyde (4%) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.2) and postfixed 1 h in 1% osmium tetroxide. Samples were dehydrated in (i) a graded ethanol series and (ii) propylene oxide and subsequently embedded in Embed-812 embedding medium (EMS, Hatfield, PA, USA). Semi-thin (0.8 μm) and ultrathin (90 nm) cross sections were cut with an ultramicrotome (Reichert & Jung model Ultracut E). Semi-thin cross sections were stained with 1% toluidine blue and viewed under a light microscopy (Optika B-600TiFL, Optika Microscopes, Ponteranica, Italy). Ultrathin cross sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM H600, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Anatomical characteristics were derived from the micrographs with ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). Light microscopy images were used to determine the mesophyll thickness between the two epidermal layers (tmes, μm), the fraction of the mesophyll tissue occupied by the intercellular air spaces (fias) (Patakas et al. 2003), and the mesophyll (Sm/S) and chloroplast (Sc/S) surface area facing intercellular air spaces per leaf area (Evans et al. 1994, Syvertsen et al. 1995, Tomás et al. 2013). All parameters were analyzed at least in four different fields of view and at three different sections. Electron microscopy images were used to determine the cell wall thickness (Tcw), cytoplasm thickness (Tcyt), chloroplast length (Lchl) and chloroplast thickness (Tchl) (Tomás et al. 2013). Three different sections and four to six different fields of view were used for measurements of each anatomical characteristic.

Mesophyll conductance modeled on the basis of anatomical characteristics

Leaf anatomical characteristics were used to estimate the gm as a composite conductance for within-leaf gas and liquid components, according to the 1D gas diffusion model of Niinemets and Reichstein (2003) as applied by Tosens et al. (2012a):

| (3) |

where gias is the gas-phase conductance inside the leaf from substomatal cavities to outer surface of cell walls, gliq is the conductance in liquid and lipid phases from outer surface of cell walls to chloroplasts, R is the gas constant (Pa m3 K−1 mol−1), Tk is the absolute temperature (K) and H is the Henry's law constant for CO2 (Pa m3 mol−1). gm is defined as a gas-phase conductance, and thus, H/(RTk), the dimensionless form of the Henry's law constant, is needed to convert gliq to corresponding gas-phase equivalent conductance (Niinemets and Reichstein 2003).

The intercellular gas-phase conductance (and the reciprocal term, rias) was obtained according to Niinemets and Reichstein (2003) as:

| (4) |

where ΔLias (m) is the average gas-phase thickness, τ is the diffusion path tortuosity (1.57 m m−1, Syvertsen et al. 1995), DA is the diffusivity of the CO2 in the air (1.51 × 10−5 m2 s−1 at 25 °C) and fias is the fraction of intercellular air spaces. ΔLias was taken as the half of the mesophyll thickness. Total liquid-phase conductance (gliq) from the outer surface of cell walls to the carboxylation sites in the chloroplasts is the sum of serial conductances in the cell wall (rcw), plasmalemma (rpl) and inside the cell (rcel,tot) (Tomás et al. 2013):

| (5) |

The conductance of the cell wall was calculated as previously described in Peguero-Pina et al. (2012). For the conductance of plasma membrane, we used an estimate of 0.0035 m s−1 as previously suggested (Tosens et al. 2012a). The conductance inside the cell was calculated following the methodology described in Tomás et al. (2013), considering two different pathways of CO2 inside the cell: one for cell wall parts lined with chloroplasts and the other for interchloroplastial areas (Tholen et al. 2012).

Analysis of partitioning changes in photosynthetic rate

The contribution analysis proposed by Buckley and Díaz-Espejo (2015) was used to partition changes in photosynthesis into contributions from the underlying variables. This new approach uses numerical integration having the advantage of avoiding the bias caused by discrete approximations like the widely used limitation analysis proposed by Grassi and Magnani (2005), and avoiding the need to compute partial derivatives for each variable. The method by Buckley and Díaz-Espejo (2015) relies instead on variable substitution in the photosynthesis model. This approach is easily extended to encompass effects of changes in any photosynthetic variable, under any conditions. Therefore, not only the contributions to photosynthesis in the Rubisco-limiting region are represented now, but also those in the RuBP regeneration region.

Two analyses were performed. First, we compared Q. robur with Q. faginea to determine the main factor responsible for the lower AN in the former species. Values in Table 4 were used to apply the contribution analysis. Second, we analyzed the effect of reduction in gs (i.e., simulating a response to VPD or soil water deficit) in the % of contribution to AN limitation. We assumed that, as gs was reduced, gm and Vc,max were maintained constant.

Table 4.

Mean values for the photosynthetic parameters analyzed at PPFD = 1500 μmol photons m−2 s−1, Tleaf = 25 °C and VPD = 1.25 kPa. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Q. robur and Q. faginea. AN, net photosynthesis; gs, stomatal conductance; E, transpiration; iWUE = AN/gS, intrinsic water use efficiency; WUE = AN/E, instantaneous water use efficiency; gm, mesophyll conductance to CO2; Ci, substomatal CO2 concentration; Cc, chloroplastic CO2 concentration; Vc,max and Jmax, maximum velocity of carboxylation and maximum capacity for electron transport; Jflu, electron transport rate estimated by chlorophyll fluorescence.

| Q. robur | Q. faginea | |

|---|---|---|

| AN (µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) | 12.9 ± 0.5a | 19.6 ± 1.1b |

| gs (mol H2O m−2 s−1) | 0.252 ± 0.013a | 0.652 ± 0.078b |

| E (mol H2O m−2 s−1) | 2.5 ± 0.02a | 6.5 ± 0.8b |

| iWUE (μmol mol−1) | 51.2 ± 1.8a | 31.7 ± 3.1b |

| WUE (μmol mol−1) | 5.1 ± 0.3a | 3.0 ± 0.2b |

| gm (mol H2O m−2 s−1) | 0.060 ± 0.005a | 0.098 ± 0.07b |

| Ci (µmmol CO2 mol−1 air) | 288 ± 7a | 293 ± 4a |

| Cc (µmmol CO2 mol−1 air) | 80 ± 2a | 95 ± 4b |

| Vc,max (µmol m−2 s−1) | 206 ± 6a | 250 ± 4b |

| Jmax (µmol m−2 s−1) | 248 ± 10a | 292 ± 14b |

| Jflu (µmol m−2 s−1) | 266 ± 8a | 306 ± 13b |

| Jmax : Vc,max | 1.21 ± 0.03a | 1.19 ± 0.04a |

Determination of total soluble protein, Rubisco “and leaf nitrogen contents

Leaves from Q. robur and Q. faginea were ground in 500 µl of ice-cold extraction buffer containing 50 mM Bicine–NaOH (pH 8.0), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetracetic acid, 5% polyvinyl pyrrolidone, 6% polyethylene glycol (PEG4000), 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM dithiothreitol and 1% protease-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC., USA). The extracts were centrifuged at 14,000g for 1 min at 4 °C and the total soluble protein (TSP) concentration in supernatant was quantified by the method of Bradford (1976). The concentration of Rubisco was determined with the gel electrophoresis method (Suárez et al. 2011, Bermúdez et al. 2012) using known concentrations of purified Rubisco from wheat as a standard for calibration.

Total leaf nitrogen (N) concentration was determined in dried leaves of Q. robur and Q. faginea using an Organic Elemental Analyzer (Flash EA 112, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

rbcL sequencing

Total genomic DNA from Q. robur and Q. faginea was isolated and purified using the DNeasy Plant Minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. The primers used for amplification and sequencing of the rbcL, the gene encoding the Rubisco large subunit, were esp2F (5′-ATGAGTT“GTAGGGAGGGAC-3′) and 1494R (5′-GATTGGGCCGAGTTTA“ATTTAC-3′) (Chen et al. 1998). Primers 414R (5′-CAAATCCTC“CAGACGTAGAGC-3′) and 991R (5′-CGGTACCAGCGTGAATAT“GAT-3′) (Chen et al. 1998) were also used only for sequencing.

Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in 50 µl using BioMix Red reagent mix (Bioline Ltd, London, UK). Polymerase chain reaction program for amplifications comprised initial cycle at 94 °C for 2 min, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 4 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and purified using Roche High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain). The amplified PCR products were sequenced with an ABI 3100 Genetic analyzer using the ABI BigDye™ Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Sequence chromatograms were checked and manually corrected and the contigs were assembled and aligned using MEGA 5.0 (Tamura et al. 2011).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard error. Student's t-tests were used to compare the trait values between Q. robur and Q. faginea. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 8.0 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The study of the morphological variables revealed an outstanding lower transpiring area in Q. faginea when compared with Q. robur, in terms of single leaf area, number of leaves, total leaf area per shoot and LAR (Table 2). In contrast, MVD and LMA were higher in Q. faginea (Table 2).

Table 2.

Leaf area, LMA, MVD, number of leaves per shoot, total leaf area per shoot and LAR for Q. robur and Q. faginea. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Q. robur and Q. faginea.

| Q. robur | Q. faginea | |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf area (cm2) | 15.2 ± 1.4a | 3.8 ± 0.2b |

| LMA (mg cm−2) | 8.94 ± 1.30a | 13.65 ± 0.65b |

| MVD (mm mm−2) | 0.53 ± 0.02a | 1.32 ± 0.03b |

| Number of leaves per shoot | 11.2 ± 0.9a | 7.5 ± 0.7b |

| Total leaf area per shoot (cm2) | 180 ± 26a | 31 ± 4b |

| LAR (m2 kg−1) | 7.8 ± 0.2a | 5.4 ± 0.1b |

The hydraulic parameters of current-year twigs showed a sevenfold higher Kh in Q. robur when compared with Q. faginea. However, this difference in Kh between both species was buffered when expressed on a sapwood area basis (Ks) (Table 3), indicative of the production of conductive tissues with a similar efficiency in both species, or on a leaf area basis (LSC) (Table 3), explained by the higher investment in leaf area of Q. robur.

Table 3.

Kh, Ks, LSC and Kleaf for Q. robur and Q. faginea. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Q. robur and Q. faginea.

| Q. robur | Q. faginea | |

|---|---|---|

| Kh (kg m s−1 MPa−1) | 24.2 × 10−7 ± 7.2 × 10−7a | 3.4 × 10−7 ± 0.9 × 10−7b |

| Ks (kg m−1 s−1 MPa−1) | 1.32 ± 0.28a | 0.75 ± 0.14a |

| LSC (kg m−1 s−1 MPa−1) | 2.0 × 10−4 ± 3.2 × 10−5a | 1.5 × 10−4 ± 4.0 × 10−5a |

| Kleaf (mmol m−2 s−1 MPa−1) | 17.9 ± 1.3a | 27.7 ± 1.5b |

At ambient CO2 concentration, 1.25 kPa of VPD and light-saturating intensity, AN, E and gs were higher in Q. faginea (19.6 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1, 6.5 mol H2O m−2 s−1 and 0.652 mol “H2O m−2 s−1, respectively) than in Q. robur (12.9 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1, 2.5 mol H2O m−2 s−1 and 0.252 mol H2O m−2 s−1, respectively) (Table 4). Both the intrinsic (iWUE = AN/gs) and the instantaneous (WUE = AN/E) water use efficiency were lower in Q. faginea (Table 4). The values of Kleaf for both species showed trends consistent with those described above for leaf gas exchange parameters: the value for Q. faginea (27.7 ± 1.5 mmol m−2 s−1 “MPa−1) was higher than that for Q. robur (17.9 ± 1.3 mmol “m−2 s−1 MPa−1) (Table 3). The differences in AN were partly associated with the greater LMA in Q. faginea when compared with Q. robur (Table 2). In fact, when the net photosynthetic rate was expressed per unit dry mass, no statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were found between Q. robur and Q. faginea (data not shown).

The mesophyll conductance to CO2 (gm) and the chloroplastic CO2 concentration (Cc) were higher in Q. faginea (Table 4). Parameterization of the Farquhar et al. (1980) model of photosynthesis yielded higher values for Vc,max and Jmax in Q. faginea, although the ratio Jmax : Vc,max did not show differences between the two species (Table 4).

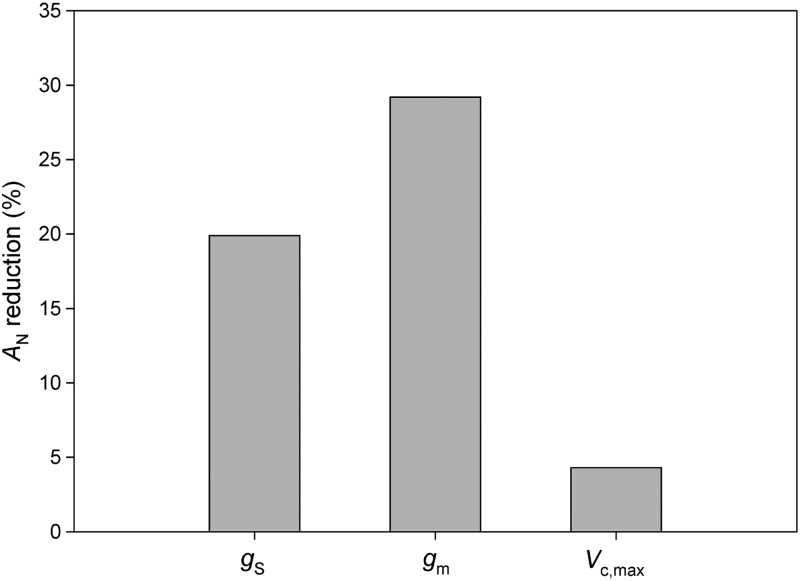

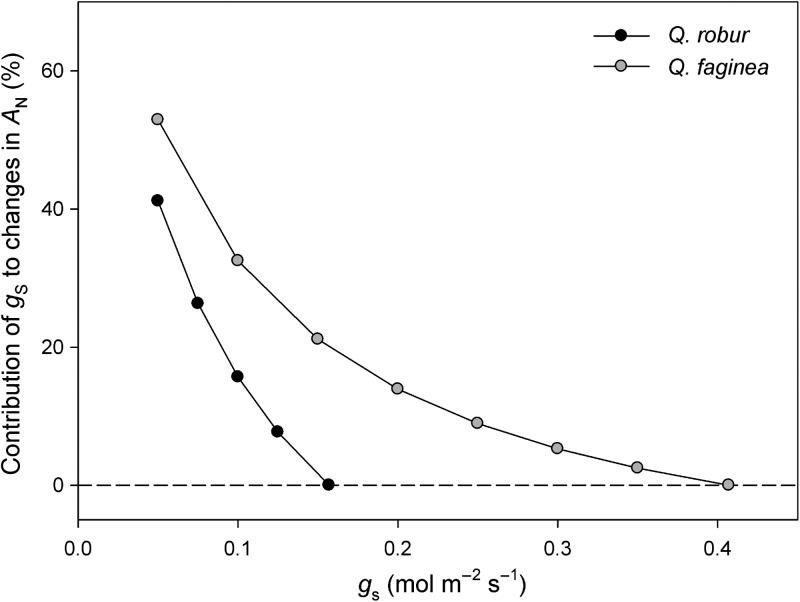

The analysis of the partitioning changes in photosynthesis revealed that AN in Q. robur and Q. faginea was mainly limited by diffusional processes. Stomatal and, especially, mesophyll conductance limitations were responsible for the lower AN measured in Q. robur in comparison with Q. faginea (Figure 2). Quercus faginea exhibited a large range of gs, achieving values up to three times higher than Q. robur. As a consequence, a 50% reduction of gs represents a AN limitation of only 15% in Q. faginea; meanwhile, it means 35% for Q. robur (Figure 3). However, when comparing identical absolute values of gs in both species, the AN limitation due to stomata is always higher in Q. faginea than in Q. robur (Figure 3), greatly due to the higher Vc,max in Q. faginea (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Contributions of individual variables (gs, stomatal conductance; gm, mesophyll conductance to CO2; Vc,max, maximum velocity of carboxylation) to the reduction in net CO2 assimilation rate (AN) shown by Q. robur using the values of Q. faginea as reference.

Figure 3.

Contribution of stomatal conductance (gs) to changes in net CO2 assimilation rate (AN) for Q. robur and Q. faginea.

Quercus robur and Q. faginea displayed contrasting anatomical features at the leaf and cell levels. The mesophyll thickness, fias, Sm/S, Sc/S and Sc/Sm were higher in Q. faginea, while Tcyt and Tchl were higher in Q. robur, and no differences were found in Tcw and Lchl (Table 5). The anatomical parameters were further used to estimate different components of the CO2 transfer resistances relative to total mesophyll resistance for both species (see Materials and methods for details). On one hand, regarding the gas phase, no differences were found in rias between both species (Table 6). On the other hand, regarding the liquid phase, the results demonstrated that Q. faginea presented lower values of rliq than Q. robur (Table 6), which can be attributed to the lower values of Tcyt and Tchl found in Q. faginea (Table 5). Consequently, the estimated value of gm was higher in Q. faginea than in Q. robur (Table 6), in agreement with the differences found in gm obtained by gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements (Table 4).

Table 5.

Leaf type, mesophyll thickness, fias, mesophyll surface area exposed to intercellular airspace (Sm/S), chloroplast surface area exposed to intercellular airspace (Sc/S), the ratio Sc/Sm, Tcw, Tcyt, Lchl and Tchl in Q. robur and Q. faginea leaves. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Q. robur and Q. faginea.

| Q. robur | Q. faginea | |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf type | Hypostomatous | Hypostomatous |

| Mesophyll thickness (μm) | 140 ± 2a | 186 ± 3b |

| fias | 0.16 ± 0.01a | 0.21 ± 0.01b |

| Sm/S (m2 m−2) | 21.9 ± 1.4a | 28.4 ± 2.0b |

| Sc/S (m2 m−2) | 9.2 ± 1.0a | 13.4 ± 1.7b |

| Sc/Sm | 0.42 ± 0.02a | 0.48 ± 0.02b |

| Tcw (μm) | 0.262 ± 0.019a | 0.270 ± 0.008a |

| Tcyt (μm) | 0.109 ± 0.036a | 0.026 ± 0.012b |

| Lchl (μm) | 4.48 ± 0.29a | 4.32 ± 0.16a |

| Tchl (μm) | 1.87 ± 0.07a | 1.21 ± 0.03b |

Table 6.

CO2 transfer resistances across the intercellular air space (rias, s m−1), the liquid phase (rliq, s m−1) and the mesophyll conductance for CO2 (gm, mol m−2 s−1) calculated from anatomical measurements in Q. robur and Q. faginea. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Q. robur and Q. faginea.

| rias (s m−1) | rliq (s m−1) | gm (mol m−2 s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q. robur | 46 ± 5a | 391 ± 21a | 0.091 ± 0.009a |

| Q. faginea | 45 ± 6a | 279 ± 18b | 0.122 ± 0.008b |

In Q. faginea, the concentration of N, TSP and Rubisco catalytic sites per leaf area were higher than in Q. robur (Table 7). The decreases in the concentration of TSP and Rubisco per leaf area in Q. robur with respect to Q. faginea were of similar magnitude, so that the ratio Rubisco/TSP was similar in both species (Table 7). Again, as stated above for AN, when the concentration of N, TSP and Rubisco was expressed per unit dry mass, no differences (P < 0.05) were found between Q. robur and Q. faginea (Table 7).

Table 7.

Leaf N, TSP and Rubisco concentrations per leaf dry mass and per leaf area for Q. robur and Q. faginea. Data are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between Q. robur and Q. faginea.

| Q. robur | Q. faginea | |

|---|---|---|

| g N/100 g | 1.90 ± 0.15a | 2.19 ± 0.18a |

| mol N m−2 | 0.12 ± 0.02a | 0.21 ± 0.03b |

| mg TSP g−1 | 32.7 ± 1.4a | 32.4 ± 0.4a |

| mg TSP m−2 | 2922 ± 130a | 4423 ± 55b |

| mg Rubisco/mg TSP | 0.33 ± 0.01a | 0.34 ± 0.01a |

| mg Rubisco g−1 | 11.0 ± 0.5a | 10.9 ± 0.3a |

| µmol Rubisco sites m−2 | 17.6 ± 0.8a | 26.7 ± 0.9b |

Discussion

In this study, we have found a clear morphological and physiological segregation between Q. robur and Q. faginea, two ‘roburoid oaks’ occurring under contrasting climatic conditions (Table 1, Figure 1). The existence of a common ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) large subunit (rbcL) (see Figure S1 available as Supplementary Data at Tree Physiology Online) confirms the genetic proximity between these species, as stated in previous studies (Olalde et al. 2002, Himrane et al. 2004). Further, the identical rbcL sequence discards the existence of evolution trends in the ‘quality’ of Rubisco (i.e., related to different catalytic constants), in contrast with recent infrageneric comparative studies (Galmés et al. 2014a, 2014b). In spite of their genetic proximity, the two species constitute two very contrasting functional types, showing a coordinated response at whole-plant level that would establish a differential physiological performance in response to climate dryness. Our results agree with recent studies that demonstrate strong interspecific correlations between hydraulic and photosynthetic traits (Brodribb et al. 2005, 2007, Sack and Holbrook 2006, Flexas et al. 2013).

Among all the studied traits, the differences found in leaf size constitute one of the most outstanding divergences between both species (Table 2). Thus, Q. faginea diminished the transpiring area, both in terms of single leaf area and number of leaves per shoot. Both traits imply a total leaf area per shoot about six times lower in Q. faginea than in Q. robur, with a direct consequence on the whole shoot transpiration in the former. A reduction in leaf size, such as that found in Q. faginea, has been proposed as one of the key traits that allows other Mediterranean oaks to withstand water deficit (Baldocchi and Xu 2007, Peguero-Pina et al. 2014). A direct benefit provided by small leaves is the improvement of the ability to supply water to transpiring leaves at shoot level in Q. faginea, offsetting the sharp difference found in Kh between both species (about seven times) for a similar Ks (Table 3). In this way, Q. faginea reached LSC values very similar to those measured for Q. robur (Table 3). An adjustment of LSC by reducing the whole-shoot leaf area has been previously reported by Peguero-Pina et al. (2014) in a comparison among Q. ilex provenances from contrasting climatic conditions. Another positive aspect of reducing leaf size in Q. faginea is the reduction of the aerodynamic resistance of leaves, which leads to a better coupling between leaf temperature and air temperature. This reduction in the aerodynamic resistance of leaves further enhances the control of transpiration by stomata (Jarvis and McNaughton 1986).

On the contrary, the reduction in the total leaf area per shoot had a negative impact on the carbon gain of Q. faginea and, through the effect on LAR, on its growth ability (Poorter and Remkes 1990). In this regard, Q. faginea presented several physiological traits that partially counteract the negative effects of leaf area reduction in terms of carbon assimilation. For instance, when compared with Q. robur, Q. faginea showed higher values for the main photosynthetic parameters (Table 4). Among them, it must be highlighted the extremely high values of gs in Q. faginea. Such high values for gs, which have been previously reported for this species (Acherar and Rambal 1992, Mediavilla and Escudero 2003, 2004), imply a high water consumption under the atmospheric evaporative demand experienced by this species during summer. The differences found in gs between both species agreed with the differences found in Kleaf and MVD (Sack and Holbrook 2006, Sack and Scoffoni 2013), confirming the existence of a coordinated response between leaf hydraulics and gas exchange (Brodribb et al. 2007).

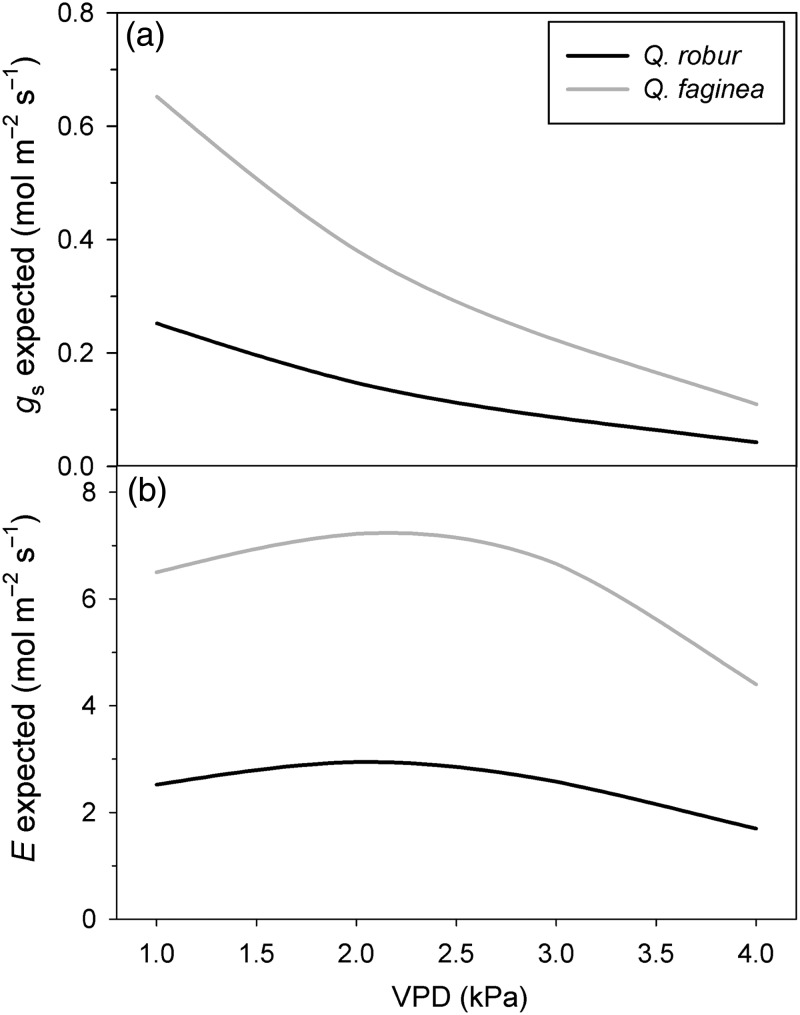

The maximum gs values found in Q. faginea can be analyzed in the context of the stomatal sensitivity (i.e., the magnitude of the reduction in gs with increasing VPD) reported by Mediavilla and Escudero (2003) for this species. According to the empirical model given by Oren et al. (1999), an exponential decrease in gs would be expected as VPD increases, ranging from the values obtained at VPD close to 1 kPa to an expected value close to 0.220 mol H2O m−2 s−1 at 3 kPa (Table 4, Figure 4a), which can be considered the maximum VPD expected value in the natural habitat of this species during the hottest period of the summer (Figure 1). The higher stomatal sensitivity of Q. faginea when compared with Q. robur is coherent with the higher gs,max measured in the former species (Oren et al. 1999) and implies the ability to cope with the higher VPD values experienced by Q. faginea through the vegetative period (Figure 1). In contrast, Q. robur showed a relatively low gs,max (as previously reported by Epron and Dreyer 1993, Rust and Roloff 2002, Arend et al. 2013) and, consequently, showed a lower stomatal sensitivity, which seems to be in accordance with the lower values of VPD registered through the vegetative period—below or close to 1 kPa—in its natural habitats (Figure 1). The transpiration values (E) calculated from the values of gs for any VPD (Figure 4b) suggest that the differential stomatal sensitivity showed by Q. robur and Q. faginea keeps quite constant the E values for both species within the range of VPD values registered in their natural habitats (Figure 1).

Figure 4.

(a) Relationship between VPD and the expected stomatal conductance (gs) and (b) relationship between VPD and the expected transpiration (E) for Q. robur and Q. faginea according to the empirical model given by Oren et al. (1999).

The high gs,max value for Q. faginea found here and in previous studies (Acherar and Rambal 1992, Mediavilla and Escudero 2003, 2004) seems to be contradictory to the capacity of this species to live in Mediterranean areas. However, the high gs,max and the subsequent high stomatal sensitivity (Figure 4a) in Q. faginea in comparison with Q. robur must be interpreted taking into account the analysis of the stomatal limitations to the CO2 photosynthetic assimilation (Figure 3). Effectively, the stomatal limitations to photosynthesis (AN) in Q. faginea start at a gs value of ∼0.4 mol m−2 s−1, which is expected to occur at a VPD value of ∼2 kPa (Figure 4a). From this value, the contribution of gs to the decrease in AN (%) is progressively higher. However, at the maximum expected VPD value at midsummer (3 kPa, Figure 1), the expected contribution of gs only diminished <20% of the maximum value of AN at 1 kPa (Figure 3). In contrast, the curve predicting the contribution of gs to changes in AN (%) in Q. robur (Figure 3) shows a quite different shape, with a very sharp increase in the contribution of gs to the decrease in AN (%) once the stomatal regulation starts. In this sense, and under the climatic conditions experienced by Q. faginea (gs <0.100 mol H2O m−2 s−1 at 3 kPa), the stomatal limitations to photosynthesis in Q. robur will be higher than 30% (Figure 3). However, the absence of atmospheric dryness in the distribution range of Q. robur (Figure 1) allows this species to maintain stable photosynthetic rates along the vegetative period (Morecroft and Roberts 1999).

Contrary to Q. robur, the vegetative period in the distribution range of Q. faginea is affected by an important seasonality, expressed in terms of temperature, precipitation and VPD (Figure 1). Therefore, Q. faginea has to cope with a drop in the soil water content during summer that negatively affects the soil water potential, consequently limiting the maximum values of gs in this species (Acherar and Rambal 1992, Mediavilla and Escudero 2003, 2004). This double limitation to gs, imposed by the stomatal sensitivity to VPD and to soil drought, may definitively limit the length of the vegetative period if the soil water reserves are depleted during the hottest and driest days of the summer. This may explain the extreme dependence of Q. faginea on edaphic conditions that ensure the maintenance of nonlimiting soil water potential values (Esteso-Martínez et al. 2006). In fact, different studies have evidenced the massive substitution of Q. faginea by the evergreen congeneric Q. ilex in most areas of the Iberian Peninsula as a consequence of the soil degradation associated with the human management of these areas (Corcuera et al. 2005a, 2005b).

On the other hand, the existence of a potential stress period during summer may be compensated by the prolongation of vegetative period along early- and mid-autumn, when temperature, water availability and VPD do not constrain the photosynthetic activity, as has been reported in several Mediterranean white oak species (Abadía et al. 1996, Mediavilla and Escudero 2003). Zhu et al. (2012) showed the strong dependence of vegetation phenology on latitude between 35°N and 70°N for North America, where a reduction in the length of the growing season of ∼5 days per degree of latitude can be expected. The clearly southern distribution area of Q. faginea (from 35°N to 43°N) compared with Q. robur (40°N to ∼60°N) (Jalas and Suominen 1976) should itself imply a longer vegetative period for the Mediterranean species, which may partially compensate for the severity of the environmental conditions in the middle of the growing season. According to this, Withington et al. (2006) found a leaf life span of 172 days (0.47 years) for Q. robur in central Poland at 51°N, while Mediavilla et al. (2001) reported a leaf life span of 208 days for Q. faginea (0.58 years) in central-western Spain at 41°N.

The higher inherent photosynthetic ability of Q. faginea when compared with Q. robur was not only a consequence of its higher Vc,max but also relies on a higher gm, which resulted in a higher chloroplastic CO2 concentration (Cc) (Table 4). The differences in gm between the two species can be partially attributed to the variation in leaf anatomical traits, i.e., Tcyt and Tchl (Table 5), that decreased rliq in Q. faginea in comparison with Q. robur (Table 6). It should be noted that the role of anatomical traits in determining the specific variability in gm has been previously reported in several studies (Tosens et al. 2012b, Tomás et al. 2013). In the present study, the gm modeled based on leaf anatomical properties was higher than that estimated using conventional methods in Q. robur and Q. faginea (Tables 4 and 6). The reasons for such biases are not fully understood but are often observed in other studies (Peguero-Pina et al. 2012, Tomás et al. 2013, Carriquí et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the relative difference in gm between the two species obtained with the two methods—gas exchange/fluorescence vs anatomical—largely supports a predominant role of internal CO2 diffusion in establishing photosynthetic differences between them.

The enhancement of all these functional traits in Q. faginea when compared with Q. robur—i.e., through the improvement of the instantaneous photosynthetic parameters—only partially counteract the negative effects of leaf area reduction in terms of carbon assimilation. Thus, taking into account the whole leaf area per shoot, Q. robur even shows an enhanced ability for carbon assimilation at whole-shoot level (data not shown), which results in a higher growth ability. On the other hand, the strong reduction in leaf area showed by Q. faginea would diminish the water losses at whole shoot level in comparison with Q. robur (data not shown), in spite of showing much higher gs values (Table 4), which may be considered a key factor for withstanding the climate dryness imposed by the Mediterranean-type climates. However, in spite of the ability of Q. faginea to occupy most areas under Mediterranean climate (Olalde et al. 2002, Benito Garzón et al. 2008), the predictions indicate a notable reduction in its potential distribution range (Sánchez de Dios et al. 2009) as a consequence of the increment in aridity. Effectively, an increase in the length or in the intensity of summer drought will have a negative influence on the functional response of Q. faginea and other Mediterranean deciduous species (Gea-Izquierdo et al. 2013), as long as it would imply a shorter time period for carbon assimilation and a lower productivity (Gea-Izquierdo and Cañellas 2014). Under these conditions, evergreen oaks—such as Q. ilex—can obtain a benefit from their more ‘conservative’ leaf strategy (Wright et al. 2004) that allows the use of other periods through the year, such as the early spring or late autumn (Corcuera et al. 2005a).

Conclusions

Quercus faginea can be regarded as an example of adaptation of a deciduous oak to the Mediterranean-type climates, as fossil records indicate (Roiron 1983, Barrón et al. 2010). In our opinion, the reduction in transpiring area both at leaf and shoot level in Q. faginea, when compared with the mesic-temperate Q. robur, is the main trait imposed by the water deficit in Mediterranean-type climates. The reduction in LAR in Q. faginea should have a negative effect of carbon gain that is partially compensated with a higher AN at the expense of a much higher maximum gs, which has been considered one key trait for classifying this species as a ‘water spender’ (Mediavilla and Escudero 2004). We propose that the extremely high gs values in Q. faginea counteract the reduction in gs imposed by the stomatal sensitivity to VPD, allowing this species to maintain high AN values through the changing conditions along the vegetative period in its natural habitat. The depletion of soil water reserves at midsummer should impose a further limitation in the vegetative activity of this species, which explain its substitution by other species (e.g., Q. ilex) in degraded soils and can also explain the extreme vulnerability of this species to an increment in aridity associated with a global climatic change (Sánchez de Dios et al. 2009).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this article are available at Tree Physiology Online.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

Financial support from Gobierno de Aragón (H38 research group) and Plan Nacional project AGL2009-07999 are acknowledged. Work of D.S.-K. is supported by a DOC INIA contract cofunded by the Spanish National Institute for Agriculture and Food Research and Technology (INIA) and the European Social Fund (ESF).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Emilio Roldán (UIB) for his help in determining leaf TSP and Rubisco content and to Arantxa Molins and Carmen Hermida (UIB) for rbcL sequencing.

References

- Abadía A, Gil E, Morales F, Montañés L, Montserrat G, Abadía J (1996) Marcescence and senescence in a submediterranean oak (Quercus subpyrenaica E.H. del Villar): photosynthetic characteristics and nutrient composition. Plant Cell Environ 19:685–694. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00403.x [Google Scholar]

- Acherar M, Rambal S (1992) Comparative water relations of four Mediterranean oak species. Vegetatio 99–100:177–184. doi:10.1007/BF00118224 [Google Scholar]

- Arend M, Brem A, Kuster TM, Günthardt-Goerg MS (2013) Seasonal photosynthetic responses of European oaks to drought and elevated daytime temperature. Plant Biol 15:169–176. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod DI. (1983) Biogeography of oaks in the Arcto-Tertiary province. Ann Mo Bot Gard 70:629–657. doi:10.2307/2398982 [Google Scholar]

- Baldocchi DD, Xu L (2007) What limits evaporation from Mediterranean oak woodlands—the supply of moisture in the soil, physiological control by plants or the demand by the atmosphere? Adv Water Resour 30:2113–2122. doi:10.1016/j.advwatres.2006.06.013 [Google Scholar]

- Barrón E, Rivas-Carballo R, Postigo-Mijarra JM, Alcalde-Olivares C, Vieira M, Castro L, Pais J, Valle-Hernández M (2010) The Cenozoic vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula: a synthesis. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 162:382–402. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2009.11.007 [Google Scholar]

- Benito Garzón M, Sánchez de Dios R, Sáinz Ollero H (2007) Predictive modelling of tree species distributions on the Iberian Peninsula during the Last Glacial Maximum and Mid-Holocene. Ecography 30:120–134. doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.04813.x [Google Scholar]

- Benito Garzón M, Sánchez de Dios R, Sainz Ollero H (2008) Effects of climate change on the distribution of Iberian tree species. Appl Veg Sci 11:169–178. doi:10.3170/2008-7-18348 [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez MA, Galmés J, Moreno I, Mullineaux PM, Gotor C, Romero LC (2012) Photosynthetic adaptation to length of day is dependent on S-sulfocysteine synthase activity in the thylakoid lumen. Plant Physiol 160:274–288. doi:10.1104/pp.112.201491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Portis AR, Nakano H, von Caemmerer S, Long SP (2002) Temperature response of mesophyll conductance. Implications for the determination of Rubisco enzyme kinetics and for limitations to photosynthesis in vivo. Plant Physiol 130:1992–1998. doi:10.1104/pp.008250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Holbrook NM (2004) Diurnal depression of leaf hydraulic conductance in a tropical tree species. Plant Cell Environ 27:820–827. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01188.x [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Holbrook NM, Zwieniecki MA, Palma B (2005) Leaf hydraulic capacity in ferns, conifers and angiosperms: impacts on photosynthetic maxima. New Phytol 165:839–846. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Field TS, Jordan GJ (2007) Leaf maximum photosynthetic rate and venation are linked by hydraulics. Plant Physiol 144:1890–1898. doi:10.1104/pp.107.101352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Díaz-Espejo A (2015) Partitioning changes in photosynthetic rate into contributions from different variables. Plant Cell Environ 38:1200–1211. doi:10.1111/pce.12459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriquí M, Cabrera HM, Conesa MÀ et al. (2015) Diffusional limitations explain the lower photosynthetic capacity of ferns as compared with angiosperms in a common garden study. Plant Cell Environ 38:448–460. doi:10.1111/pce.12402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZD, Wang XQ, Sun HY, Han Y, Zhang ZX, Zou YP, Lu AM (1998) Systematic position of the Rhoipteleaceae: evidence from nucleotide sequences of rbcL gene. Acta Phytotaxon Sin 36:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Corcuera L, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E (2002) Functional groups in Quercus species derived from the analysis of pressure-volume curves. Trees 16:465–472. doi:10.1007/s00468-002-0187-1 [Google Scholar]

- Corcuera L, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E (2004) Effects of a severe drought on growth and wood anatomical properties of Quercus faginea. IAWA J 25:185–204. doi:10.1163/22941932-90000360 [Google Scholar]

- Corcuera L, Morales F, Abadía A, Gil-Pelegrín E (2005a) Seasonal changes in photosynthesis and photoprotection in a Quercus ilex subsp. ballota woodland located in its upper altitudinal extreme in the Iberian Peninsula. Tree Physiol 25:599–608. doi:10.1093/treephys/25.5.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcuera L, Morales F, Abadía A, Gil-Pelegrín E (2005b) The effect of low temperatures on the photosynthetic apparatus of Quercus ilex subsp. ballota at its lower and upper altitudinal limits in the Iberian Peninsula and during a single freezing-thawing cycle. Trees 19:99–108. doi:10.1007/s00468-004-0368-1 [Google Scholar]

- Denk T, Grimm GW (2009) Significance of pollen characteristics for infrageneric classification and phylogeny in Quercus (Fagaceae). Int J Plant Sci 170:926–940. doi:10.1086/600134 [Google Scholar]

- Denk T, Grimm GW (2010) The oaks of western Eurasia: traditional classifications and evidence from two nuclear markers. Taxon 59:351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Ducousso A, Bordacs S (2004) EUFORGEN Technical Guidelines for genetic conservation and use for pedunculate and sessile oaks (Quercus robur and Q. petraea). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, 6 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Epron D, Dreyer E (1993) Long-term effects of drought on photosynthesis of adult oak trees [Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. and Quercus robur L.] in a natural stand. New Phytol 125:381–389. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03890.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteso-Martínez J, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E (2006) Competitive effects of herbs on Quercus faginea seedlings inferred from vulnerability curves and spatial-pattern analyses in a Mediterranean stand (Iberian System, northeast Spain). Ecoscience 131:378–387. doi:10.2980/i1195-6860-13-3-378.1 [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S, Setchell BA, Hudson GS (1994) The relationship between CO2 transfer conductance and leaf anatomy in transgenic tobacco with a reduced content of Rubisco. Aust J Plant Physiol 21:475–495. doi:10.1071/PP9940475 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149:78–90. doi:10.1007/BF00386231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Díaz-Espejo A, Berry JA, Galmés J, Cifre J, Kaldenhoff R, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbó M (2007a) Analysis of leakage in IRGA's leaf chambers of open gas exchange systems: quantification and its effects in photosynthesis parameterization. J Exp Bot 58:1533–1543. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ortuño MF, Ribas-Carbó M, Díaz-Espejo A, Flórez-Sarasa ID, Medrano H (2007b) Mesophyll conductance to CO2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 175:501–511. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Scoffoni C, Gago J, Sack L (2013) Leaf mesophyll conductance and leaf hydraulic conductance: an introduction to their measurement and coordination. J Exp Bot 64:3965–3981. doi:10.1093/jxb/ert319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Andralojc PJ, Kapralov MV, Flexas J, Keys AJ, Molins A, Parry MAJ, Conesa MÀ (2014a) Environmentally driven evolution of Rubisco and improved photosynthesis and growth within the C3 genus Limonium (Plumbaginaceae). New Phytol 203:989–999. doi:10.1111/nph.12858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Andralojc PJ, Conesa MÀ, Keys AJ, Parry MAJ, Flexas J (2014b) Expanding knowledge of the Rubisco kinetics variability in plant species: environmental and evolutionary trends. Plant Cell Environ 37:1989–2001. doi:10.1111/pce.12335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gea-Izquierdo G, Cañellas I (2014) Local climate forces instability in long-term productivity of a Mediterranean oak along climatic gradients. Ecosystems 17:228–241. doi:10.1007/s10021-013-9719-3 [Google Scholar]

- Gea-Izquierdo G, Fernández-de-Uña L, Cañellas I (2013) Growth projections reveal local vulnerability of Mediterranean oaks with rising temperatures. For Ecol Manag 305:282–293. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2013.05.058 [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais JM, Baker NR (1989) The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim Biophys Acta 990:87–92. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(89)80016-9 [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Magnani F (2005) Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell Environ 28:834–849. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01333.x [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD (1992) Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiol 98:1429–1436. doi:10.1104/pp.98.4.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himrane H, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E (2004) Morphological and ecophysiological variation of the hybrid oak Quercus subpyrenaica (Q. faginea × Q. pubescens). Trees 18:566–575. doi:10.1007/s00468-004-0340-0 [Google Scholar]

- Jalas J, Suominen J (eds) (1976) Atlas Florae Europaeae. Distribution of vascular plants in Europe. 3. Salicaceae to Balanophoraceae. The Committee for Mapping the Flora of Europe & Societas Biologica Fennica Vanamo, Helsinki, 128 pp. [maps 201–383]. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis PG, McNaughton KG (1986) Stomatal control of transpiration: scaling up from leaf to region. Adv Ecol Res 15:1–49. doi:10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60119-1 [Google Scholar]

- Jato V, Rodríguez-Rajo FJ, Méndez J, Aira MJ (2002) Phenological behaviour of Quercus in Ourense (NW Spain) and its relationship with the atmospheric pollen season. Int J Biometeorol 46:176–184. doi:10.1007/s00484-002-0132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuzawa K. (1995) Leaf phenology as an optimal strategy for carbon gain in plants. Can J Bot 73:158–163. doi:10.1139/b95-019 [Google Scholar]

- Kovar-Eder J, Kvacek Z, Zastawniak E, Givulescu R, Hably L, Mihajlovic D, Teslenko Y, Walther H (1996) Floristic trends in the vegetation of the Paratethys surrounding areas during Neogene time. In: Bernor R, Fahlbusch V, Mittmann HW (eds) The evolution of Western Eurasia Later Neogene faunas. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Krall JP, Edwards GE (1992) Relationship between photosystem II activity and CO2 fixation in leaves. Physiol Plant 86:180–187. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb01328.x [Google Scholar]

- Kremer A, Abbott AG, Carlson JE, Manos PS, Plomion C, Sisco P, Staton ME, Ueno S, Vendramin GG (2012) Genomics of Fagaceae. Tree Genet Genomes 8:583–610. doi:10.1007/s11295-012-0498-3 [Google Scholar]

- Kvacek Z, Walther H (1989) Palaeobotanical studies in Fagaceae of the European Tertiart. Plant Syst Evol 162:213–229. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb01328.x [Google Scholar]

- Laisk AK. (1977) Kinetics of photosynthesis and photorespiration in C3-plants. Nauka, Moscow, Russia: (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Manos PS, Doyle JJ, Nixon KC (1999) Phylogeny, biogeography, and processes of molecular differentiation in Quercus subgenus Quercus (Fagaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 12:333–349. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr S, Wieser G, Bauer H (2006) Xylem temperatures during winter in conifers at the alpine timberline. Agric For Meteorol 137:81–88. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.02.013 [Google Scholar]

- Mediavilla S, Escudero A (2003) Stomatal responses to drought at a Mediterranean site: a comparative study of co-occurring woody species differing in leaf longevity. Tree Physiol 23:987–996. doi:10.1093/treephys/23.14.987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediavilla S, Escudero A (2004) Stomatal responses to drought of mature trees and seedlings of two co-occurring Mediterranean oaks. For Ecol Manag 187:281–294. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2003.07.006 [Google Scholar]

- Mediavilla S, Escudero A, Heilmeier H (2001) Internal leaf anatomy and photosynthetic resource-use efficiency: interspecific and intraspecific comparisons. Tree Physiol 21:251–259. doi:10.1093/treephys/21.4.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecroft MD, Roberts JM (1999) Photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of mature canopy Oak (Quercus robur) and Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) trees throughout the growing season. Funct Ecol 13:332–342. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1999.00327.x [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Reichstein M (2003) Controls on the emission of plant volatiles through stomata: a sensitivity analysis. J Geophys Res 108:4211 doi:10.1029/2002JD002626 [Google Scholar]

- Ogaya R, Peñuelas J (2007) Leaf mass per area ratio in Quercus ilex leaves under a wide range of climatic conditions. The importance of low temperatures. Acta Oecol 31:168–173. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2006.07.004 [Google Scholar]

- Olalde M, Herrán A, Espinel S, Goicoechea PG (2002) White oaks phylogeography in the Iberian Peninsula. For Ecol Manag 156:89–102. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00636-3 [Google Scholar]

- Oren R, Sperry JS, Katul GG, Pataki DE, Ewers BE, Phillips N, Schäfer KVR (1999) Survey and synthesis of intra- and interspecific variation in stomatal sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit. Plant Cell Environ 22:1515–1526. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00513.x [Google Scholar]

- Patakas A, Kofidis G, Bosabalidis AM (2003) The relationships between CO2 transfer mesophyll resistance and photosynthetic efficiency in grapevine cultivars. Sci Hortic 97:255–263. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(02)00201-7 [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Flexas J, Galmés J, Niinemets Ü, Sancho-Knapik D, Barredo G, Villarroya D, Gil-Pelegrín E (2012) Leaf anatomical properties in relation to differences in mesophyll conductance to CO2 and photosynthesis in two related Mediterranean Abies species. Plant Cell Environ 35:2121–2129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Sancho-Knapik D, Barrón E, Camarero JJ, Vilagrosa A, Gil-Pelegrín E (2014) Morphological and physiological divergences within Quercus ilex support the existence of different ecotypes depending on climatic dryness. Ann Bot 114:301–313. doi:10.1093/aob/mcu108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedallu C, Gégout JC, Perez V, Lebourgeois F (2013) Soil water balance performs better than climatic water variables in tree species distribution modelling. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 22:470–482. doi:10.1111/geb.12012 [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Remkes C (1990) Leaf area ratio and net assimilation rate of 24 wild species differing in relative growth rate. Oecologia 83:553–559. doi:10.1007/BF00317209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiron P. (1983) Nouvelle étude de la macroflore plio-pléistocène de Crespià (Catalogne, Espagne). Geobios 16:687–715. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(83)80087-4 [Google Scholar]

- Rust S, Roloff A (2002) Reduced photosynthesis in old oak (Quercus robur): the impact of crown and hydraulic architecture. Tree Physiol 22:597–601. doi:10.1093/treephys/22.8.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L, Holbrook NM (2006) Leaf hydraulics. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57:361–381. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L, Scoffoni C (2013) Leaf venation: structure, function, development, evolution, ecology and applications in the past, present and future. New Phytol 198:983–1000. doi:10.1111/nph.12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Dios R, Benito-Garzón M, Sainz-Ollero H (2009) Present and future extension of the Iberian submediterranean territories as determined from the distribution of marcescent oaks. Plant Ecol 204:189–205. doi:10.1007/s11258-009-9584-5 [Google Scholar]

- Scoffoni C, Rawls M, McKown A, Cochard H, Sack L (2011) Decline of leaf hydraulic conductance with dehydration: relationship to leaf size and venation architecture. Plant Physiol 156:832–843. doi:10.1104/pp.111.173856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez R, Miró M, Cerdà V, Perdomo JA, Galmés J (2011) Automated flow-based anion-exchange method for high-throughput isolation and real-time monitoring of RuBisCO in plant extracts. Talanta 84:1259–1266. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2011.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen JP, Lloyd J, McConchie C, Kriedemann PE, Farquhar GD (1995) On the relationship between leaf anatomy and CO2 diffusion through the mesophyll of hypostomatous leaves. Plant Cell Environ 18:149–157. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.1995.tb00348.x [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Ethier G, Genty B, Pepin S, Zhu X (2012) Variable mesophyll conductance revisited: theoretical background and experimental implications. Plant Cell Environ 35:2087–2103. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás M, Flexas J, Copolovici L et al. (2013) Importance of leaf anatomy in determining mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2 across species: quantitative limitations and scaling up by models. J Exp Bot 64:2269–2281. doi:10.1093/jxb/ert086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosens T, Niinemets Ü, Vislap V, Eichelmann H, Castro Díez P (2012a) Developmental changes in mesophyll diffusion conductance and photosynthetic capacity under different light and water availabilities in Populus tremula: how structure constrains function. Plant Cell Environ 35:839–856. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosens T, Niinemets Ü, Westoby M, Wright IJ (2012b) Anatomical basis of variation in mesophyll resistance in eastern Australian sclerophylls: news of a long and winding path. J Exp Bot 63:5105–5119. doi:10.1093/jxb/ers171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentini R, Epron D, De Angelis P, Matteucci G, Dreyer E (1995) In situ estimation of net CO2 assimilation, photosynthetic electron flow and photorespiration in Turkey oak (Q. cerris L.) leaves: diurnal cycles under different levels of water supply. Plant Cell Environ 18:631–640. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.1995.tb00564.x [Google Scholar]

- van Ommen Kloeke AEE, Douma JC, Ordoñez JC, Reich PB, van Bodegom PM (2012) Global quantification of contrasting leaf life span strategies for deciduous and evergreen species in response to environmental conditions. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 21:224–235. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00667.x [Google Scholar]

- Vilagrosa A, Bellot J, Vallejo VR, Gil-Pelegrín E (2003) Cavitation, stomatal conductance, and leaf dieback in seedlings of two co-occurring Mediterranean shrubs during an intense drought. J Exp Bot 54:2015–2024. doi:10.1093/jxb/erg221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withington JM, Reich PB, Oleksyn J, Eissenstat DM (2006) Comparisons of structure and life span in roots and leaves among temperate trees. Ecol Monogr 76:381–397. [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M et al. (2004) The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428:821–827. doi:10.1038/nature02403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Tian H, Xu X, Pan Y, Chen G, Lin W (2012) Extension of the growing season due to delayed autumn over mid and high latitudes in North America during 1982–2006. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 21:260–271. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00675.x [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.