Abstract

Pulmonary migratory infiltrates (PMI) are observed in a few diseases. We report here a case of PMI attributed to Mycoplasma pneumonia (Mp) infection. The patient’s past medical history was characterized by fleeting and/or relapses of patchy opacification or infiltrates of parenchyma throughout the whole lung field except for left lower lobe radiographically. Serological assays revealed an elevation of IgG antibody specific to Mp and its fourfold increase in convalescent serum. Histopathological findings showed polypoid plugs of fibroblastic tissue filling and obliterating small air ways and interstitial infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells in the vicinal alveolar septa. The patient was treated with azithromycin which resulted in a dramatic improvement clinically and imageologically. In spite of the increasing incidence of Mp, the possible unusual imaging manifestation and underlying mechanism haven’t attracted enough attention. To our knowledge, there are rare reports of such cases.

Keywords: Pulmonary migratory infiltrates (PMI), Mycoplasma pneumonia (Mp), organizing pneumonia, azithromycin

Introduction

Pulmonary migratory infiltrates (PMI) are commonly seen in eosinophilic pneumonia (Loeffler’s syndrome), cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, parasitic infestations, Churg-Strauss syndrome, drug reactions etc. Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp), a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia which has nonspecific symptoms such as wheezing, coughing, fever etc., have previously been reported with diverse radiology presentations (1,2). However, the association of Mp and PMI has been seldom described in literatures before. Herein, we report a well-documented case of PMI due to Mp infection and review the pertinent literature.

Case representation

A nonsmoking 47-year-old woman with hysteromyoma had recurrent episodes of clinical infectious manifestations in recent three months before admitted to our hospital (Table 1). Her past imaging results characterized by fleeting and/or relapse of patchy opacification or infiltrates arrested our attention.

Table 1. Clinical presentation and medical history of this patient outside of our hospital.

| Clinical variables | June 5, 2013–June 26, 2013 | June 28, 2013–July 13, 2013 | August 20, 2013–September 2, 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Fever (>39 °C); nonproductive cough; chest congestion |

Fever; intermittent cough | Fever (38 °C); fleeting chest pain; discomfort below xiphoid |

| Laboratory data† | |||

| WBC (4–10 g/L)‡ | 13.4 (82.7% neutrophils) | 10.5 (75% neutrophils) | 7.69 |

| CRP (<8 mg/L)‡ | 96.0 | 29.2 | 7.27 |

| Blood cultures | NP | NP | NP |

| CAT (<1:32)‡ | NP | NP | 1:256 |

| Radiography† | Lobar air-space opacities in the right lower lung field (Figure 1) | Consolidation in the left upper lobe | Patchy opacification with air bronchogram in the right upper lung field and small area of ground-glass opacity in the left upper field |

| Treatment | Cefuroxime for 6 days | Cefepime for 2 weeks | Mezlocillin for 12 days |

| Outcome | Fever (fluctuating around 39 °C); WBC 12.1 g/L (85.8% neutrophils); CRP 23 mg/L; a new lesion of consolidation in the left upper lobe |

Little cough; diffused nodular opacities in the left upper field |

Occasional chest pain; patchy opacification in the right lower lobe |

†, results obtained on admission respectively; ‡, normal values are in parentheses. WBC, white blood cells; CRP, C-reactive protein; NP, not performed; CAT, cold-agglutinin titer.

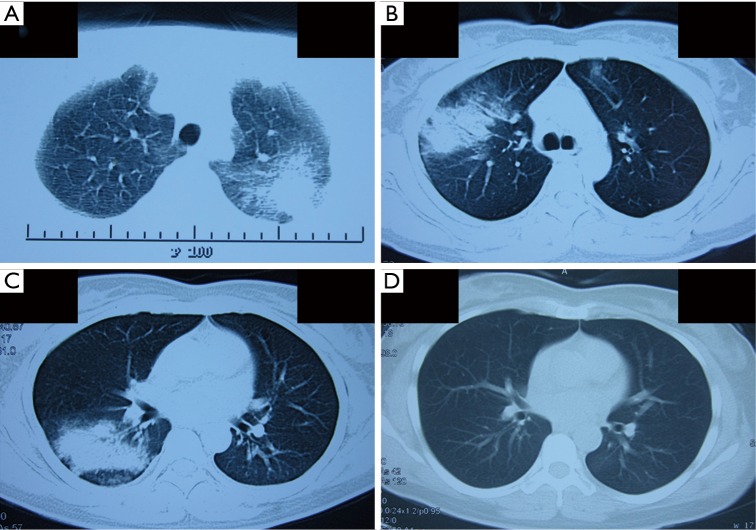

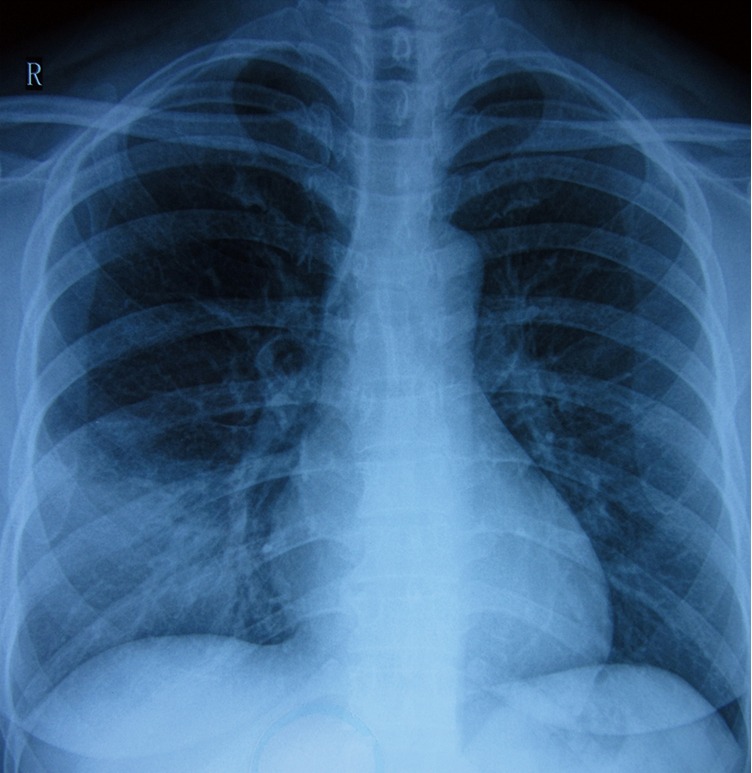

A chest roentgenogram revealed lobar air-space opacities in the right lower lung field at the onset of disease (Figure 1). Cefuroxime was given intravenously as empirical treatment for 6 days which leaded to rare relief clinically and laboratorially. Before transferred to another hospital, she was evaluated by computed tomography (CT) scan, indicating a new lesion of consolidation in the left upper lobe (Figure 2A). The change of antibiotic treatment during her second hospitalization resulted in great improvement as measured by chest roentgenogram other than diffused nodular opacities in the left upper field (not shown). She felt good until the relapse 1 month later and a CT scan on presentation showed patchy opacification with air bronchogram in the right upper lung field and small area of ground-glass opacity in the left upper field (Figure 2B). She was also found to have elevated cold-agglutinin titer (CAT) (1:256). After 12 days’ administration of mezlocillin, the patient still had occasional chest pain and a repeated CT scan revealed recurrence of patchy opacification in the right lower lobe (Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph at the beginning, demonstrating right lower-lobe air-space opacities.

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography (CT) scan presenting as pulmonary migratory infiltrates (PMI). (A) CT scan after the first hospitalization indicates a new lesion of consolidation in the left upper lobe; (B) CT scan on the third presentation shows patchy opacification with air bronchogram in the right upper lung field and small area of ground-glass opacity in the left upper field; (C) CT scan after the third hospitalization shows patchy opacification in the right lower lobe; (D) CT scan obtained after 7 days treatment of azithromycin shows complete resolution of the lesion in the right lower lobe.

On admission in our hospital, the patient complained of intermittent cough and chest congestion. Physical examination revealed low-grade fever (37.5 °C) and decreased breath sounds in right lower lung field. Blood routine examination disclosed the following values: white blood cells (WBC) count, 6.01×109/L (10.2% monocytes), hemoglobin (104 g/L) with C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factors, blood biochemical indicator detection, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies all within normal limits. Culture of blood and sputum samples for bacteria and fungi was found to be negative. There was no increase in percentage of eosinophils in BALF. No malignant cells or infectious agents were detected in the BALF and the percentage of inflammatory cells in BALF was within normal range. Besides, we didn’t find a clue of parasites or other atypical pathogens as verified by negative results of serum antibodies respectively. However, IgG antibody in serum specific to Mp, determined by ELISA (GmbH Germany), was detected positive with a reactivity 60 U/mL (where positive result for Mp IgG was >30 U/mL), which indicated a possible long term reinfection with the organism (3).

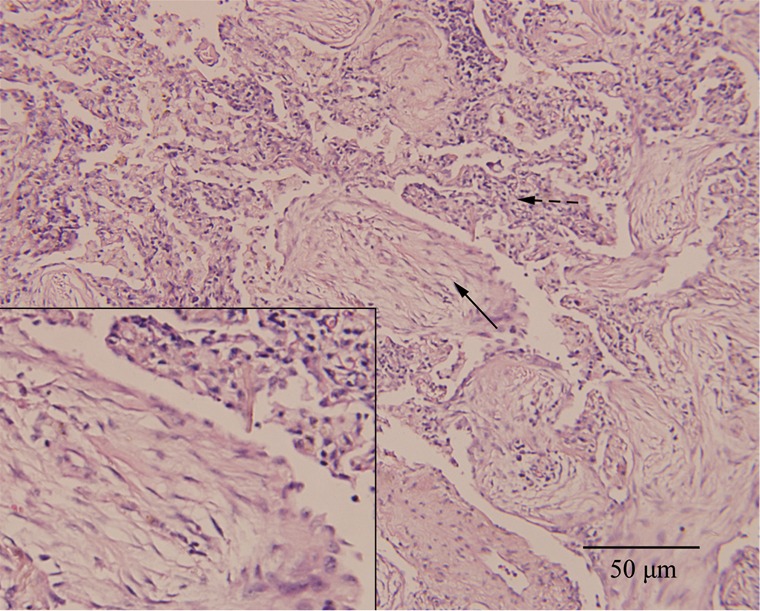

The patient was treated with azithromycin (500 mg/d) intravenously which resulted in a dramatic improvement of clinical symptoms. A CT scan obtained on the seventh hospital day showed complete resolution of the right lower patchy opacification, without new infiltrate appearing in other lobes (Figure 2D). Notably, her transbronchial lung biopsy performed on the second hospital day revealed immature polypoid plugs of fibroblastic tissue obliterating respiratory bronchioles and adjacent alveolar ducts (Figure 3). Alveolar septa within the areas of intraluminal fibrosis also contained interstitial infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells. These results were consistent with histopathological changes in organizing pneumonia.

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of right lower lobe transbronchial lung biopsy revealing immature polypoid plugs of fibroblastic tissue obliterating respiratory bronchioles and adjacent alveolar ducts (solid arrow). Interstitial infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells within neighbouring alveolar septa are also presented (dashed arrow) (hematoxylin-eosin stain, large image ×200, inset ×400).

She continued oral administration of azithromycin for 10 days after discharge from hospital. Four weeks after hospital discharge, her Mp IgG reactivity in serum was 265 U/mL. On subsequent follow-up over 6 months, the patient had no complaints with periodic chest roentgenographic findings unremarkable.

Discussion

PMI was initially recognized from eosinophilic pneumonia (Loeffler’s syndrome) (4). Some other conditions, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, parasitic infestations, Churg-Strauss syndrome, drug reactions etc., can also cause PMI (5-7). However, our patient seemed not to be trapped in causes mentioned above due to negative results of eosinophilic in BALF, serum parasitic antibodies or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, recovery without corticosteroid, and a plain medical history. Until now, no literature has described the association of PMI with hysteromyoma. In our case, a long-term Mp reinfection was most likely to be responsible because of the increased CAT (1:256), a positive serum Mp IgG antibody and its fourfold increase in convalescent serum (3,8). Besides, azithromycin, which has widely been accepted to be anti-inflammatory and efficient for Mp, leads to both clinical and radiographic improvements.

Mp accounts for about 15% to 20% of all community-acquired pneumonia cases and is commonly associated with outbreaks (9). Although previous reports showed that ground-glass attenuation and air-space opacification which was patchy and segmental or nonsegmental in distribution were common radiological features of Mp infection, a few cases presenting as PMI have been reported (10-13). The clinical characteristics of those cases are summarized in Table 2. The patients who were confirmed to be infected by Mp through distinct methods could be male or female, and their ages ranged from 11 to 71 years. The onset of symptoms was characterized by fever in all the cases which could be accompanied by cough, muscle ache, sore throat etc. WBC and neutrophils were elevated concomitantly in two patients, as in ours, while WBC and eosinophils were elevated concomitantly in only one patient whose serum IgE was also found to be increased. All the cases recovered after treated with antibiotics specifically against atypical organisms, corticosteroids, or a combination of both. Our patient responded well to azithromycin, and no additional corticosteroids were administered.

Table 2. Cases of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) infections associated with PMI in the literature.

| Source | Age (yr) | Clinical features | Imaging manifestations | Histopathological findings | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foy et al., 1971 | 40 | Fever (38 °C), nonproductive cough, muscle ache; WBC: 11.3 g/L (82% neutrophils); throat culture positive for Mp; CF antilipid antibody titer for Mp: 1:8 |

Incomplete consolidation of left lower lobe changed into infiltrate in right perihilar region 4 and a half years later | NP | Erythromycin (500 mg twice daily); symptoms resolved |

| Miyagawa et al., 1991 | 71 | Fever, malase; ESR: 120 mm/h; anti-mycoplasma antibody titer raised (not in detail) |

PMI (not in detail) | Polypoid granulation tissue with nuclear debris in the lumen of respiratory bronchiole, re-epithelialization on surface of organization tissue | Minocycline; symptoms resolved |

| Llibre et al., 1997 | 57 | Fever (37.7 °C), cough, exertional dyspnea; WBC: 13.9 g/L (72% neutrophils); ESR: 100 mm/h; anti-mycoplasma IgG antibody first titer 1.05 and second titer 2.95 (4 weeks later) |

Bilateral, mainly peripheral, migratory patchy infiltrates in the lower right lobe and left upper lobe | Fibroblastic tissue within bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and peribronchiolar alveolar spaces, interstitial infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells | Oral prednisone; symptoms resolved |

| Yang et al., 2008 | 11 | Fever (38.3 °C), shortness of breath, sore throat; WBC: 12.2 g/L (8.3% eosinophils); serum IgE: 770 IU/mL; PCR detection positive for Mp |

Four pulmonary masses in bilateral lower lobes and left upper lobe changed into interval development of diffuse tiny centrilobular nodules and mild hilar lymphadenopathy | NP | Azithromycin and budesonide nebulizer; symptoms resolved |

WBC, white blood cells; Mp, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; CF, complement-fixation; NP, not performed; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PMI, pulmonary migratory infiltrates.

The imaging manifestations of PMI attributed to Mp infection can be diverse. In a case reported by Foy et al., the patient presented as incomplete consolidation in the left lower lobe which turned into infiltrate in the right perihilar region 4 and a half years later (10). Yang described an 11-year-old boy who developed transient pulmonary masses in the early stage of Mp infection (13). Of interest, Llibre et al. reported another case that initially had a segmental infiltrate in the lower right lobe and an alveolar infiltrate in the left upper lobe from chest roentgenogram (12). And a repeated chest roentgenogram obtained 1 month later revealed bilateral, mainly peripheral, migratory patchy infiltrates. But those infiltrates were distributed within areas that were affected on admission. Our patient was quite unusual in that the patchy or nodular opacifications and infiltrates of parenchyma were migratory throughout the whole lung field except for left lower lobe in just 3 months, which were recorded by the initial chest roentgenogram and all the later CT scans. To our knowledge, there are no reports of Mp-induced PMI in which such extensive lung fields were involved.

Transbronchial lung biopsy of the present patient showed fibroblastic tissue in respiratory bronchioles and adjacent alveolar ducts and interstitial infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells in morbid sites. Those pathological findings, which resembled changes in organizing pneumonia, can be recognized as nonspecific reactions to infectious injury (14). It has already been reported that atypical organisms’ infection will lead to organizing pneumonia in some cases who can recover without corticosteroids as ours (8,15). Our patient presented as both PMI and organizing pneumonia, facts that can be interpreted as follows: The infection of Mp to lower respiratory tract activates macrophages which then begin phagocytosis. Macrophages secrete various cytokines and chemokines attracting more neutrophils and lymphocytes to the site. On one hand, the amplified immune response (including the producing of Mp specific IgA, IgM, IgG, and T-cell-mediated immunity) eliminates organisms in the lesion, but on the other hand, it exacerbates disease through inflammatory damage, such as deterioration of infected cells and excessive proliferation of fibrous tissues. After the elimination of pathogens, the body is able to repair the damaged cells and degrade the newly formed fibrous tissues, process which was thought as histopathologically reversible by Epler et al. in organizing pneumonia patients (14). However, due to the intracellular location and variant in surface antigens, Mp would induce a recurrence or new lesions in the lung (16).

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first well-documented case of Mp infection case presenting as PMI. Several reports can be summed up to a point that PMI with organizing pneumonia should be more defined as a syndrome complex which can been seen in patients with a variety of causes (11,13,15). Though rare, Mp infection must be considered in patients with this pattern and poor resolution of empiric anti-infection treatment.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This research was supported in part by Grants 81274143 and 81173610 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Natori H, Koga T, Fujimoto K, et al. Organizing pneumonia associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Jpn J Radiol 2010;28:688-91. 10.1007/s11604-010-0473-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reittner P, Müller NL, Heyneman L, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: radiographic and high-resolution CT features in 28 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:37-41. 10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spuesens EB, Fraaij PL, Visser EG, et al. Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract of symptomatic and asymptomatic children: an observational study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001444. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadeem S, Nasir N, Israel RH. Löffler's syndrome secondary to crack cocaine. Chest 1994;105:1599-600. 10.1378/chest.105.5.1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein DM, Bennett MR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia with migratory pulmonary infiltrates. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;158:515-7. 10.2214/ajr.158.3.1738986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sablé-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:632-8. 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faller M, Quoix E, Popin E, et al. Migratory pulmonary infiltrates in a patient treated with sotalol. Eur Respir J 1997;10:2159-62. 10.1183/09031936.97.10092159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coultas DB, Samet JM, Butler C. Bronchiolitis obliterans due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae. West J Med 1986;144:471-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klement E, Talkington DF, Wasserzug O, et al. Identification of risk factors for infection in an outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory tract disease. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1239-45. 10.1086/508458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foy HM, Nugent CG, Kenny GE, et al. Repeated Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia after 4 and one-half years. JAMA 1971;216:671-2. 10.1001/jama.1971.03180300053014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyagawa Y, Nagata N, Shigematsu N. Clinicopathological study of migratory lung infiltrates. Thorax 1991;46:233-8. 10.1136/thx.46.4.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llibre JM, Urban A, Garcia E, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with acute Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:1340-2. 10.1086/516124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang E, Altes T, Anupindi SA. Early Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection presenting as multiple pulmonary masses: an unusual presentation in a child. Pediatr Radiol 2008;38:477-80. 10.1007/s00247-007-0718-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epler GR, Colby TV, McLoud TC, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1985;312:152-8. 10.1056/NEJM198501173120304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imokawa S, Yasuda K, Uchiyama H, et al. Chlamydial infection showing migratory pulmonary infiltrates. Intern Med 2007;46:1735-8. 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su CJ, Chavoya A, Dallo SF, et al. Sequence divergency of the cytadhesin gene of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun 1990;58:2669-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]