Abstract

Background

The clinicopathological features and optimum treatment of esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) are hardly known due to its rarity. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study to analyze the clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with surgically resected esophageal NEC.

Methods

We collected clinicopathological data on consecutive limited disease stage esophageal NEC patients who underwent esophagectomy with regional lymphadenectomy in West China Hospital from January 2007 to December 2013.

Results

A total of forty-nine patients were analyzed retrospectively. The mean age of the patients was 58.4±8.2 years with male predominance. Fifty-five percent of the esophageal NEC were located in the middle thoracic esophagus. Histologically, 28 (57.1%) patients were found to be small cell NECs. Fifty-one percent of the patients were found to have lymph node metastasis. According to the 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, 9 patients were at stage I, 21 patients stage II, and 19 patients stage III. Twenty-six patients (53.1%) received adjuvant therapy. After a median follow-up of 44.8 months [95% confidence interval (CI), 35.2–50.4 months], the median survival time of the patients was 22.4 months (95% CI, 14.0–30.8 months). The 1-year and 3-year survival rates for the whole cohort patients were 74.9% and 35.3%, respectively. In univariate analysis, TNM staging, lymph node metastasis and adjutant therapy significantly influenced survival time. In multivariate analysis, TNM staging was the only independent prognostic factor.

Conclusions

Esophageal NEC has a poor prognosis. The 2009 AJCC TNM staging system for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma may also fit for esophageal NEC. Surgery combined with adjuvant therapy may be a good option for treating limited disease stage esophageal NEC. Further prospective studies defining the optimum therapeutic regimen for esophageal NEC are needed.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), esophagus, surgery, prognosis

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are defined as epithelial neoplasms with predominant neuroendocrine differentiation, which mainly arise from gut and bronchopulmonary systems (1,2). The 2010 World Health Organization classification for digestive system NENs have classified NENs into three categories [low-grade (G1) neuroendocrine tumor, intermediate-grade (G2) neuroendocrine tumor, and high-grade (G3) neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC)] based on the histopathologic analysis (3). NEC (mainly consisting of small cell type and non-small cell type) (4) is one kind of NENs with poor differentiation, and it is graded as G3 with a mitotic count of >20 per 10 high power fields and/or a Ki-67 index >20% (5). Data from the US Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database suggest that the incidence and prevalence of NENs have increased substantially over the past three decades as awareness and diagnostic techniques have improved (1). However, esophageal NENs were extremely rare, which represent only 0.04–1.4% of the gastrointestinal NENs reported (2,6,7). Even though most of the esophageal NENs are reported to be esophageal NEC (2,3), esophageal NEC is still exceedingly rare with poor prognosis. Lee et al. (7) have reported only 7 cases (0.3%) of esophageal NEC in an analysis of 2,037 NENs arising in different gastrointestinal sites. Owing to its rarity, there has been no concrete data with large sample size published on its clinical features or prognosis (7-9). As a result, its clinicopathological characteristics and optimum treatment are far from being well established up to date. In order to elucidate the clinicopathological features and optimum treatment protocols of esophageal NEC, studies concerning esophageal NEC with relatively large sample size are badly needed. Therefore, this retrospective study of 49 surgical resection cases was performed to analyze the clinical characteristics and potential prognostic factors for patients with surgically resected esophageal NEC and provide more valuable data about esophageal NEC.

Methods

We collected and reviewed the records of 49 consecutive patients with pathologically and immunohistochemically diagnosed NECs of the esophagus after esophagectomy with regional lymphadenectomy in West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Chengdu, China) from January 2007 to December 2013. Data concerning demographic data, pathologic findings, TNM staging, tumor location, adjutant therapy, and survival time were all collected and surveyed. The pathologic findings included type of the NECs, lymph node involvement, lymphovascular invasion, and immunohistochemical profiles of chromogranin A, synaptophysin, neuron specific enolase (NSE), cluster differentiation 56 (CD56) and Ki-67 index. The location of the tumor in the esophagus was determined on the basis of endoscopic findings and was divided into three segments: cervical/upper (15 to 25 cm from the incisor teeth), middle (25 to 30 cm), and lower (30 to 40 cm) segments of the esophagus. The tumor was staged according to The Veterans’ Administration Lung Study Group system which is originally applied to small cell lung cancer (10) and 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system (7th edition) for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (11). We performed the final follow-up by telephone, mail or outpatient department visit in October 2015. Survival time was calculated from the day of esophagectomy to the date of death or last follow-up. Informed consent was obtained from all these patients before taking part in our study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital (No.201649). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Corp, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were represented as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables or number (%) for categorical data. To estimate the association between eligible variables and survival time, Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank tests were used. The independent prognostic factors were evaluated using Cox’s hazard regression model. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient’s characteristics

All patients in our study were clinically diagnosed with resectable esophageal NENs preoperatively (clinical stage I or stage II preoperatively). The clinical characteristics of the 49 patients were summarized in Table 1. The mean age of all patients was 58.4±8.2 years (range, 42–75 years) with a 2.5:1 male predominance. The pathologic findings of the patients showed 28 (57.1%) cases of small cell NEC. Eleven (22.4%) cases of mixed NEC which were all mixed with squamous cell carcinoma were found among all patients. Over half esophageal NEC were located in the middle segment of the esophagus (55.1%). Approximately, half of the patients (51.0%) were found to have lymph node metastasis. Lymphovascular invasion was found in 6 patients (12.2%). Detailed immunohistochemical profiles of the esophageal NEC could only be obtained from a small percent of these patients, and therefore, immunohistochemical profiles were not analyzed in present study. All patients were in limited disease stage according to The Veterans’ Administration Lung Study Group system. As for TNM staging, 9 patients were at stage I, 21 patients stage II, and 19 patients stage III. More than half of the patients (53.1%) received adjutant therapy (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients with esophageal NEC in our study (N=49).

| Characteristics | No. in group (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 58.4±8.2 (42–75) years |

| <60 years | 24 (49.0) |

| ≥60 years | 25 (51.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 (71.4) |

| Female | 14 (28.6) |

| Pathology | |

| Small cell carcinoma | 28 (57.1) |

| Undetermined | 21 (42.9) |

| Histology homology | |

| Pure | 38 (77.6) |

| Mixed | 11 (22.4) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| Yes | 25 (51.0) |

| No | 24 (49.0) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Yes | 6 (12.2) |

| No | 43 (87.8) |

| Tumor location | |

| Upper segment | 5 (10.2) |

| Middle segment | 27 (55.1) |

| Lower segment | 17 (34.7) |

| TNM stage | |

| Stage I | 9 (18.4) |

| Stage II | 21 (42.9) |

| Stage III | 19 (38.8) |

| Esophagectomy | |

| Left thoracotomy | 44 (89.8) |

| Right thoracotomy | 3 (6.1) |

| Transhiatal esophagectomy | 2 (4.1) |

| Adjutant therapy | |

| Yes | 26 (53.1) |

| No | 23 (46.9) |

NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Treatment and prognosis

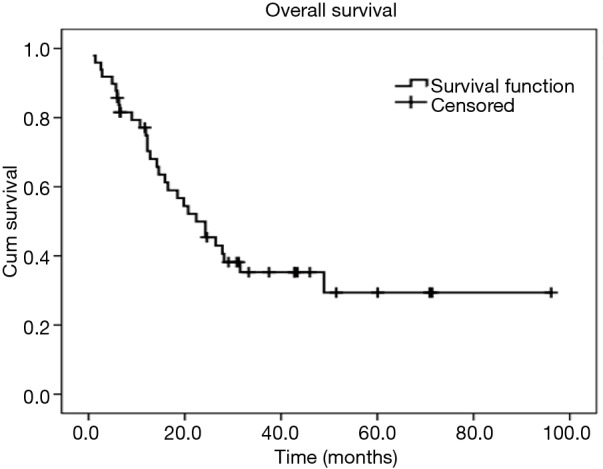

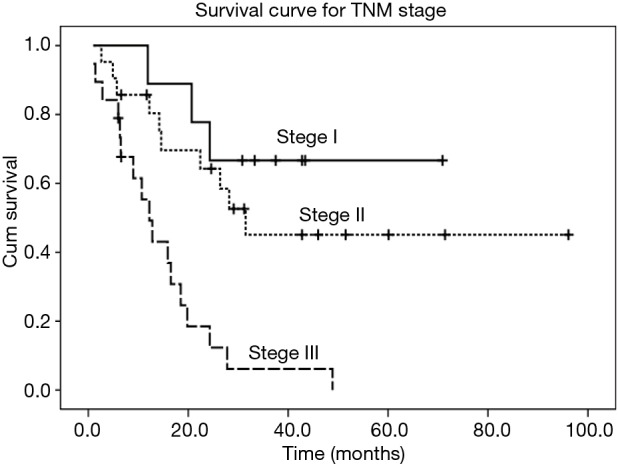

All of those 49 patients were treated with radical esophagectomy with regional lymphadectomy with a preoperative diagnosis of limited disease stage. Forty-four patients received left transthoracic esophagectomy with two-field lymphadectomy, while three patients had right transthoracic esophagectomy with two-field lymphadectomy and other two patients received transhiatal esophagectomy with regional lymphadectomy. Forty-seven patients had R0 resection, while one patient had R1 resection and another one patient had R2 resection. Due to the preoperative diagnosis of resectable esophageal NECs (clinical stage I or stage II preoperatively), none patients had received any neoadjuvant therapy. However, after surgery, 26 patients received chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or chemoradiotherapy due to lymph node metastasis or lymphovascular invasion. During a median follow-up of 44.8 months (95% CI: 35.2–50.4 months), 30 patients were decreased, and 11 patients were alive, while 8 patients (16.3%) were lost to follow-up. The median survival time of the patients was 22.4 months (95% CI: 14.0–30.8 months). The 1-year and 3-year survival rates for the whole patients were 74.9% and 35.3%, respectively (Figure 1). In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, patients with adjutant therapy achieved significantly longer survival time than patients without (median survival time: >28.2 and 14.6 months respectively, P=0.017). Patients with lymph node metastasis had significantly lower survival time than patients without (P=0.021). Also, there was statistically significant difference among patients with different TNM staging (P<0.001) (Figure 2). However, there were no significant differences in survival time with regard to patients’ sex (P=0.904), age (P=0.750), histology homology (P=0.103), lymphovascular invasion (P=0.685), or tumor location (P=0.705) in the univariate analyses (Table 2). Multivariate analysis indicated that only TNM stage was a significant independent prognostic factor for overall survival, and patients with higher stage was associated with shorter survival. In our cohort, patients with stage I [risk ratio (RR) =0.14; 95% CI, 0.04–0.50; P=0.002] or stage II (RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.11–0.58; P=0.001) yielded significantly longer survival time than those with stage III (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival for patients with esophageal NEC after surgical resection [Median overall survival: 22.4 months (95% CI, 14.0–30.8 months)]. NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of survival for patients with different TNM stages (P<0.001).

Table 2. Univariate analyses of survival on clinical and pathologic factors.

| Variables | Median survival (months) | 1-year survival rate (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <60 years | 20.7 | 74.3 | 0.750 |

| ≥60 years | 26.7 | 75.2 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24.3 | 76.0 | 0.904 |

| Female | 18.5 | 71.4 | |

| Histology homology | |||

| Pure | 19.8 | 75.9 | 0.103 |

| Mixed | >22.4 | 72.7 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Yes | 16.5 | 70.8 | 0.021* |

| No | >31.5 | 78.9 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||

| Yes | 12.2 | 66.7 | 0.685 |

| No | 24.3 | 76.2 | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Upper segment | 19.8 | 80.0 | 0.705 |

| Middle segment | 24.3 | 77.4 | |

| Lower segment | 18.5 | 70.1 | |

| TNM stage | |||

| Stage I | >24.3 | 88.9 | <0.001* |

| Stage II | 31.5 | 85.7 | |

| Stage III | 12.2 | 55.4 | |

| Adjutant therapy | |||

| Yes | >28.2 | 83.5 | 0.017* |

| No | 14.6 | 65.2 |

*, P<0.05.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of survival on clinical and pathologic factors.

| Variables | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Stage Ia | 0.14 (0.04–0.50) | 0.002* |

| Stage IIa | 0.26 (0.11–0.58) | 0.001* |

| Age | – | 0.852 |

| Sex | – | 0.596 |

| Histology homology | – | 0.382 |

| Lymph node metastasis | – | 0.285 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | – | 0.771 |

| Tumor location | – | 0.805 |

| Adjutant therapy | – | 0.191 |

a, stage III was set as reference (RR=1.00). *, P<0.05.

Discussion

Due to the rarity of esophageal NEC, this retrospective study was conducted to provide more information about its clinical characteristics as well as prognostic factors related to it. In our present study, we found that the mean age of the patients with esophageal NEC was 58.4 years with male predominance, and the common locations of the tumor were middle (55.1%) and lower (34.7%) segments of the esophagus. After a median follow-up of 44.8 months (95% CI, 35.2–50.4 months), the median survival time of the patients with esophageal NEC was 22.4 months (95% CI, 14.0–30.8 months), and TNM stage of the tumor was the only independent prognostic factor for overall survival. To our knowledge, present study of 49 cases with surgical resection was one of the largest studies with a relatively long-term follow-up period that was sufficient to provide valuable clinical characteristics and prognostic evaluation of esophageal NEC.

The demographic data of the patients with esophageal NEC revealed a mean age of 58.4 years (range, 42–75 years) and male predominance (male/female ratio = 2.5:1) that were similar to those reported in previous studies (9,12,13), and this demographic characteristics were also similar to those of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (14) which is the commonest type of esophageal cancer in Chinese people. In our cohort, patients with esophageal NEC (median survival: 22.4 month) showed shorter overall survival time as compared to patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma reported previously (median survival: 54.8 months) (15), suggesting the poor prognosis of esophageal NEC.

Small cell carcinoma accounted for 57.1% of all types of esophageal NEC in this study, which agreed with the study reported by Huang et al. (9) showing a proportion of 88% of small cell carcinoma in Chinese patients with esophageal NEC. Our study showed that the common locations of the esophageal NEC were in the middle (55.1%) and lower (34.7%) segments of the esophagus, which was quite consistent with other studies (8,9,13) as well as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (15). One possible reason is small cell carcinoma of esophagus was believed to originate from the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylase (APUD) cells of the esophagus, which commonly exist in the distal esophagus (16). Another possible reason is that esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma may be related to Merkel cells which was found to be more numerous in the middle esophageal region (17). The mixed esophageal NEC accounted for 22.4% of all esophageal NEC in our study, and all these mixed esophageal NEC was found to mix with squamous cell carcinoma, which may to some degree support the hypothesis raised by Huang (9) that esophageal NEC in Chinese may represent as an undifferentiated tumor in the spectrum of esophageal squamous neoplasm.

Given the rarity of esophageal NEC compared to squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, there is no unique TNM staging system for this cell-type. Even though many studies proposed to use The Veterans’ Administration Lung Study Group system which is originally applied to small cell lung cancer (10), for practical purposes, esophageal NEC were also commonly staged according to TNM staging system for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (9,12,18). Therefore, we staged our patients with 2009 AJCC TNM staging system for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, even though all of these patients were limited disease stage according to The Veterans’ Administration Lung Study Group system (10). In our survival analysis, we found that the stage of the patients was significantly related to prognosis and that TNM staging was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival. Our results showed that patients with early TNM stage of esophageal NEC had a better prognosis. Patients with early stage (I/II) yielded significantly longer survival time than those with stage III esophageal NEC in both univariate and multivariate analyses, which was consistent with the concept that the prognosis of esophageal cancer correlated reasonably with the stage of the disease. As there is no standard and accurate TNM staging system proposed for esophageal NEC available yet, our results suggested that TNM staging system by AJCC for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma seemed to be a good alternative for esophageal NEC before an optimum TNM staging system of esophageal NEC is available. Therefore, our study indicated that the 2009 AJCC TNM staging system (7th edition) for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma could be predictive of the survival in esophageal NEC and that this TNM staging system could fit for esophageal NEC (19). Future studies are required, however, to improve the stratification and prognostic value of the staging system.

Due to lack of sufficient data about the clinicopathological characteristics of esophageal NEC, there were no standard treatment strategies available yet. The role of surgery in esophageal NEC still remains controversial (20), even though some of the similar studies have revealed long-term survival after surgical resection of esophageal NEC (21). However, in present study, patients have showed a median survival time of 22.4 months after radical esophagectomy and regional lymphadectomy with or without adjutant therapy for esophageal NEC. To our best knowledge, recently published studies with relatively large cases exploring the role of surgery in treating limited disease stage esophageal NEC have yield a median survival time of 10.1 to 28.5 months (9,16,22-24), while patients treated with chemoradiotherapy alone yielded a median survival time of 8.0 to 16.1 months (25-27). Therefore, it seemed that surgery may benefit patients with limited stage esophageal NEC, but the role of surgery in treating esophageal NEC still remains to be confirmed and validated (28). In our univariate analysis, adjutant therapy could significantly increase survival time of the patients (median survival time: >28.2 and 14.6 months respectively, P=0.017), which was also commonly observed in previous studies (16,29). However, in our multivariate analysis, adjuvant therapy was not an independent prognostic factor. Regarding the association between adjuvant therapy and survival on univariate but not multivariate analysis, it should be mentioned that this may be due to small sample size, inherent biases in the retrospective study, or heterogeneity in the patient population. Therefore, we still believe that chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy apart from surgery could play an important role in managing limited disease stage esophageal NEC (10,16,20,30).

There are several limitations in our present study. First, a major limitation of our study is the retrospective study design, and therefore, some data (such as the number of lymph nodes dissected and the detailed information about adjuvant therapy) were omitted during analysis due to lack of sufficient information, which may limit the validity of our overall analysis. Second, our retrospective study had a relatively high rate of loss to follow-up (16.3%), which could inevitably influence our results. Another limitation of our study is that we did not obtain enough immunohistochemical data of NEC. As a result, we only focused on clinical characteristics of the patients even though we knew clearly that immunohistochemical profile could influence the survival of the patients. Therefore, the overall results had to be interpreted with caution. Even though our sample was relatively large for this rare disease, more studies concerning esophageal NEC are needed to confirm and update our findings as well as optimum treatment strategies for this rare tumor.

Conclusions

Esophageal NEC is a rare but aggressively malignant tumor with poor prognosis. Our study on 49 cases of esophageal NEC with surgical resection showed that the 2009 AJCC TNM staging system (7th edition) for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma seemed to be an option for staging esophageal NEC. Surgery with adjuvant therapy seemed to be a good option for treating limited disease stage esophageal NEC. Further prospective studies on a larger scale are needed to define the optimum therapeutic regimen as well as staging system for esophageal NEC.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:61-72. 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70410-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estrozi B, Bacchi CE. Neuroendocrine tumors involving the gastroenteropancreatic tract: a clinicopathological evaluation of 773 cases. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1671-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park MI. Endoscopic treatment for early foregut neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Endosc 2013;46:450-5. 10.5946/ce.2013.46.5.450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klöppel G. Classification and pathology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer 2011;18 Suppl 1:S1-16. 10.1530/ERC-11-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li QL, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for foregut neuroendocrine tumors: an initial study. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:5799-806. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gastrointestinal Pathology Study Group of Korean Society of Pathologists , Cho MY, Kim JM, et al. Current Trends of the Incidence and Pathological Diagnosis of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (GEP-NETs) in Korea 2000-2009: Multicenter Study. Cancer Res Treat 2012;44:157-65. 10.4143/crt.2012.44.3.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CG, Lim YJ, Park SJ, et al. The clinical features and treatment modality of esophageal neuroendocrine tumors: a multicenter study in Korea. BMC Cancer 2014;14:569. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun JP, Zhang MF, Hou JH, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 21 cases. BMC Cancer 2007;7:38. 10.1186/1471-2407-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Q, Wu H, Nie L, et al. Primary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 42 resection cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:467-83. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826d2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen WW, Wang F, Chen S, et al. Detailed analysis of prognostic factors in primary esophageal small cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:1975-81. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Ishwaran H, et al. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: data-driven staging for the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Cancer Staging Manuals. Cancer 2010;116:3763-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng C, Shen S, Zhang X, et al. Limited stage small cell carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and prognostic analysis of 27 cases. Rare Tumors 2013;5:e6. 10.4081/rt.2013.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funakoshi S, Hashiguchi A, Teramoto K, et al. Second-line chemotherapy for refractory small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus that relapsed after complete remission with irinotecan plus cisplatin therapy: Case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett 2013;5:117-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Jiang Y, Wu C, et al. Comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival between eastern and western population with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:1780-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang HX, Hou X, Liu QW, et al. Tumor location does not impact long-term survival in patients with operable thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:1861-6. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SB, Yang JS, Yang WP, et al. Treatment and prognosis of limited disease primary small cell carcinoma of esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2011;24:114-9. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmse JL, Carey FA, Baird AR, et al. Merkel cells in the human oesophagus. J Pathol 1999;189:176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Ma L, Bao H, et al. Clinical, pathological and prognostic characteristics of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms in China: a retrospective study. BMC Endocr Disord 2014;14:54. 10.1186/1472-6823-14-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang SY, Mao WM, Du XH, et al. The 2002 AJCC TNM classification is a better predictor of primary small cell esophageal carcinoma outcome than the VALSG staging system. Chin J Cancer 2013;32:342-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jatoi A, Miller RC. Should we recommend surgery to patients with limited small cell carcinoma of the esophagus? J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1373-6. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818dd98f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muguruma K, Ohira M, Tanaka H, et al. Long-term survival of advanced small cell carcinoma of the esophagus after resection: a case report. Anticancer Res 2013;33:595-600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka T, Matono S, Nagano T, et al. Surgical management for small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2010;23:502-5. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu XJ, Luo JD, Ling Y, et al. Management of small cell carcinoma of esophagus in China. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:1181-7. 10.1007/s11605-013-2204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maru DM, Khurana H, Rashid A, et al. Retrospective study of clinicopathologic features and prognosis of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1404-11. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816bf41f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yau KK, Siu WT, Wong DC, et al. Non-operative management of small cell carcinoma of esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:487-90. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vos B, Rozema T, Miller RC, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a multicentre Rare Cancer Network study. Dis Esophagus 2011;24:258-64. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima Y, Zenda S, Minashi K, et al. Non-surgical approach to small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: does this rare disease have the same tumor behavior as SCLC? Int J Clin Oncol 2012;17:610-5. 10.1007/s10147-011-0332-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kukar M, Groman A, Malhotra U, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a SEER database analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:4239-44. 10.1245/s10434-013-3167-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie MR, Xu SB, Sun XH, et al. Role of surgery in the management and prognosis of limited-stage small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:476-82. 10.1111/dote.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv J, Liang J, Wang J, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1460-5. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818e1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]