Abstract

AIM: To determine the efficacy of rectally administered naproxen for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP).

METHODS: This double-blind randomized control trial conducted from January 2013 to April 2014 at the Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center in Rasht, Iran. A total of 324 patients were selected from candidates for diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP by using the simple sampling method. Patients received a single dose of Naproxen (500 mg; n = 162) or a placebo (n = 162) per rectum immediately before ERCP. The overall incidence of PEP, incidence of mild to severe PEP, serum amylase levels and adverse effects were measured. The primary outcome measure was the development of pancreatitis onset of pain in the upper abdomen and elevation of the serum amylase level to > 3 × the upper normal limit (60-100 IU/L) within 24 h after ERCP. The severity of PEP was classified according to the duration of therapeutic intervention for PEP: mild, 2-3 d; moderate 4-10 d; and severe, > 10 d and/or necessitated surgical or intensive treatment, or contributed to death.

RESULTS: PEP occurred in 12% (40/324) of participants, and was significantly more frequent in the placebo group compared to the naproxen group (P < 0.01). Of the participants, 25.9% (84/324) developed hyperamylasemia within 2 h of procedure completion, among whom only 35 cases belonged to the naproxen group (P < 0.01). The incidence of PEP was significantly higher in female sex, in patients receiving pancreatic duct injection, more than 3 times pancreatic duct cannulations, and ERCP duration more than 40 min (Ps < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding the procedures or factors that might increase the risk of PEP, sphincterotomy, precut requirement, biliary duct injection and number of pancreatic duct cannulations. In the subgroup of patients with pancreatic duct injection, the rate of pancreatitis in the naproxen group was significantly lower than that in the placebo (6 patients vs 23 patients, P < 0.01, RRR = 12%, AR = 0.3, 95%CI: 0.2-0.6). Naproxen reduced the PEP in patients with ≥ 3 pancreatic cannulations (P < 0.01, RRR = 25%, AR = 0.1, 95%CI: 0.1-0.4) and an ERCP duration > 40 min (P < 0.01, RRR = 20%, AR = 0.9, 95%CI: 0.4-1.2).

CONCLUSION: Single dose of suppository naproxen administered immediately before ERCP reduces the incidence of PEP.

Keywords: Naproxen, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Pancreatic duct injection, Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Pancreatitis, Serum amylase

Core tip: Acute pancreatitis is the most common serious complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP); prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) has become more challenging. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is effective in this condition. This study evaluated the efficacy of rectally administered naproxen for the prevention of PEP in composition with placebo immediately before ERCP.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis is the most common complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), with an incidence rate of 1%-10% that can reach 40% or more, depending on the presence of risk factors[1-5]. Factors predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) include young age, female sex, pancreas divisum, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, previous ERCP-induced pancreatitis, multiple attempts for pancreatic duct cannulation, and pancreatic duct injection[6,7]. Although most cases of PEP are clinically mild or moderate in severity, 10% present severe manifestations[8,9].

ERCP complications may be minimized by reducing pancreatic secretion, interrupting inflammatory cascades, relaxing the sphincter of Oddi, and preventing intra-acinar trypsinogen activation infection[10,11]. Several pharmacologic agents, including octreotide[12], diclofenac[13,14], and recombinant interleukin-10[15,16], have been investigated to reduce the incidence and severity of PEP. Additionally, the protease inhibitors gabexate mesylate[17], and somatostatin[18,19] had been shown are effective in preventing PEP, particularly when administered as an intra-venous infusion[20,21].

Evidence suggests that the patient’s inflammatory response to pancreatic duct imaging and instrumentation contribute to the development of PEP[7,22-27]. As phospholipase A2 may play a vital role in the initial inflammatory cascade of acute pancreatitis[24], identifying pharmacologic agents that inhibit or disturb this cascade may prevent or limit the pancreatitis and its consequences. In some randomized controlled trials, various Oral and suppository of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have shown promising prophylactic activity with regard to PEP[13,14,28-30]. However, different result were seen about the effectiveness of the intraduodenal indomethacin[30,31]. NSAIDs are easily administered, inexpensive, and relatively safe when given as a single dose, making them an attractive treatment option. Despite these benefits of NSAIDs and findings of the recent meta-analysis[32,33] indicated that rectal diclofenac or indomethacin reduce the incidence and severity of PEP, results of the several studies appear to contradict these conclusions[10,34-36]. Tilak Shah et al[35] mentioned several questions in this area; comparison between various NSAID, higher dose of drug and different rout of administration. Additionally, there are some study[37,38] reported NSAIDs can cause acute pancreatitis with the highest risk for diclofenac (OR = 5.0, 95%CI: 4.2-5.9) and the lowest for naproxen (OR = 1.1, 95%CI: 0.7-1.7)[39]. Therefore, we conducted a double-blind, randomized, and controlled clinical trial to evaluate the prophylactic effect of a naproxen suppository for the prevention of PEP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Participants were serially enrolled as they were seen for diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP at the gastroenterology ward of Razi Hospital, a referral center in Rasht, Iran between January 2013 and April 2014. Patients over 18 years of age who were scheduled to undergo ERCP and willing to provide written informed consent for study participation were included. Patients who had acute or active pancreatitis, a history of chronic pancreatitis and/or previous endoscopic sphincterotomy, active peptic ulcer disease, rectal disease, aspirin-induced asthma, use of NSAIDs during the preceding two weeks, hypersensitivity to NSAIDs, renal dysfunction, or were pregnant or breastfeeding, were ineligible for the study.

Study design

The protocol for this randomized, controlled clinical trial (IRCT201105301155N14) was approved by the ethics committee of the Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center of Guilan University of Medical Science, and written informed consent (per the Helsinki declaration) was obtained from each participant. Eligible participants (n = 324) were selected from candidates for diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP by using the simple sampling method. The sample size was based on the frequency of pancreatitis in the placebo group (P1 = 0.1)[28] compared to the study drug group (P2 = 0.04) with α = 0.05 and β = 20%. Selected patients were randomly assigned using permuted-block randomization to receive either a naproxen (500 mg; Behvazan Pharmacy Co., Tehran, Iran) (n = 162) or placebo (n = 162) suppository immediately before ERCP. Concealed envelopes with naproxen or placebo, which appeared identical, were dispensed in sequence. Study participants, ERCP physicians, and nurses who administered treatment were unaware of the nature of the drugs. The group assignment was only known by the programmer of the database used during the study.

ERCP was performed by using a standard therapeutic duodenoscope (Olympus CO.) with the patient under local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine and after premedication by intravenous administration of 0.05 mg/kg of Midazolam or in cases with contraindication, intravenous administration 1 mg/kg pethidine. Blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation were monitored with automated devices. Contrast medium (Meglumine Compound 76%) was injected manually, under fluoroscopic guidance. ERCPs were carried out by 3 experienced endoscopists, with a mean number of sphincterotomy procedures performed of about 5 to 7 per week.

Outcome and data measurements

The primary outcome measure was the development of pancreatitis, defined according to the guideline of Cotton et al[7] as onset of pain in the upper abdomen and elevation of the serum amylase level to > 3 × the upper normal limit (60-100 IU/L) within 24 h after ERCP. The severity of PEP was classified according to the duration of therapeutic intervention for PEP: mild, 2-3 d; moderate 4-10 d; and severe, > 10 d and/or necessitated surgical or intensive treatment, or contributed to death[7].

Serum amylase was measured before, 2 h after, and any time the patients complained of pain within 24 h after ERCP; otherwise, it was routinely measured 24 h after ERCP. After 2 h, patients with normal serum amylase or no history of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting were permitted to resume oral intake. All patients with prolonged pancreatitis symptoms (> 48 h) were assessed for complications of pancreatitis (abscess, pseudocyst, or fluid collection) by CT.

Demographic characteristics, risk factors, ERCP procedural elements, and follow-up data were collected at the time of the procedure and 24 h after ERCP by a trained physician who was unaware of study-group assignments. ERCP duration, the number of biliary and pancreatic cannulations, findings of the biliary and/or pancreatic duct, and interventions such as sphincterotomy, papillary balloon dilation, and stenting were recorded.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed χ2 test was used to analyze the difference in the proportion of patients with PEP in the naproxen and placebo groups. Data are expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Additional exploratory subgroup analyses were performed according to age, sex, and procedure, and are reported as relative risk (RR), absolute risk (AR) and relative risk reduction (RRR). All comparisons were carried out on a two-tailed basis. Statistical analysis was carried out with the SPSS (version 16) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ninety-five percent significant intervals (CI) for the proportions were calculated.

RESULTS

There were 78 (48.1%) women in the naproxen group and 73 (45.1) women in the control group. The mean age ± SD of the patients in the intervention group was 46.3 ± 8.3, and in the control group it was 44.7 ± 9.7. The characteristics of trial participants are presented in Table 1. PEP occurred in 12% (40/324) of participants, and was significantly more frequent in the placebo group (28/162, 17%) compared to the naproxen group (12/162, 7.4%) (P < 0.01). Of the participants, 25.9% (84/324) developed hyperamylasemia within 2 h of procedure completion, among whom only 35 cases belonged to the naproxen group (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics n (%)

| Characteristic | Naproxen (n = 162) | Placebo (n = 162) |

| Age, yr | 46.3 ± 8.3 | 44.7 ± 9.7 |

| Female | 78 (48.1) | 73 (45.1) |

| Pancreatitis severity | ||

| Mild | 8 (20.0)b | 18 (45.0) |

| Moderate | 4 (10.0)b | 10 (25.0) |

| Severe | 0 (0)b | 0 (0) |

P < 0.01 vs Placebo. Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Analyses in different group indicated that the incidence of PEP was significantly higher in patients receiving pancreatic duct injection, cases with 3 times or more pancreatic duct cannulations, ERCP duration > 40 min and female sex (Ps < 0.01) (Table 2). Logistic regression analysis of possible risk factors for PEP indicated that pancreatic duct injection, duration of ERCP, female sex and age were significant risk factors (Ps < 0.05) (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding the procedures or factors that might increase the risk of PEP, including, sphincterotomy, precut requirement and biliary duct injection.

Table 2.

Incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis

| Variable | Naproxen1 | Placebo2 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 9/12b | 19/28 |

| Male | 3/12 | 9/28 |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 40 | 5/12 | 10/28 |

| > 40 | 7/12 | 18/28 |

| Sphincterotomy | ||

| Yes | 8/129 | 23/119 |

| No | 4/33 | 5/43 |

| Precut required | 2/31 | 2/31 |

| Pancreatic duct injection | ||

| Yes | 6/75b | 23/84 |

| No | 6/82 | 5/83 |

| Pancreatic duct cannulations | ||

| ≥ 3 | 2/6b | 10/23 |

| ≤ 2 | 3/6 | 14/23 |

| ERCP duration (min) | ||

| > 40 | 4/12b | 12/28 |

| < 40 | 8/12 | 16/28 |

| Biliary duct injection | ||

| Yes | 9/134 | 24/135 |

| No | 3/23 | 4/25 |

Pancreatitis/naproxen (12/162, 7.4%);

Pancreatitis/placebo (28/162, 17%).

P < 0.01 vs Placebo.

Table 3.

Risk factors for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis

| Variable |

Pancreatitis, n |

OR | RR (95%CI) | RRR (%) | AR (%) | ||

| Yes | No | ||||||

| Group | 0.4b | 0.42 (0.22-0.81) | 58 | -138 | |||

| Naproxen | 12 | 150 | |||||

| Placebo | 28 | 134 | |||||

| Sex | 3b | 2.67 (1.40- 5.07) | 167 | 62.54 | |||

| Female | 28 | 123 | |||||

| Male | 12 | 161 | |||||

| Age (yr) | 2.4b | 2.2 (1.22-3.96) | 120 | 54.54 | |||

| < 40 | 15 | 63 | |||||

| > 40 | 25 | 261 | |||||

| Sphincterotomy | 1 | 1.05 (0.52-2.11) | 5 | 4.76 | |||

| Yes | 31 | 217 | |||||

| No | 9 | 67 | |||||

| Pancreatic duct injection | 2.1b | 1.88 (1.06-3.32) | 88 | 46.81 | |||

| Yes | 29 | 130 | |||||

| No | 16 | 149 | |||||

| Pancreatic duct cannulations | 2.1 | 1.87 (0.93-3.74) | 87 | 46.52 | |||

| ≥ 3 | 12 | 37 | |||||

| ≤ 2 | 14 | 93 | |||||

| ERCP duration (min) | 2.6b | 2.30 (1.29-4.09) | 130 | 56.52 | |||

| > 40 | 16 | 54 | |||||

| < 40 | 24 | 218 | |||||

| Biliary duct injection | 1.7 | 1.66 (0.76-3.63) | 66 | 39.75 | |||

| Yes | 33 | 236 | |||||

| No | 7 | 88 | |||||

P < 0.01 vs Placebo. OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk; RRR: Relative risk reduction; AR: Absolute risk.

In the subgroup of patients with pancreatic duct injection, the rate of pancreatitis in the naproxen group was significantly lower than that in the placebo group (6 patients vs 23 patients; P < 0.01, RRR = 12%, AR = 0.3, 95%CI: 0.2-0.6). Naproxen reduced the PEP in patients with ≥ 3 pancreatic cannulations (P < 0.01, RRR = 25%, AR = 0.1, 95%CI: 0.1-0.4) and an ERCP duration > 40 min (P < 0.01, RRR = 20%, AR = 0.9, 95%CI: 0.4-1.2).

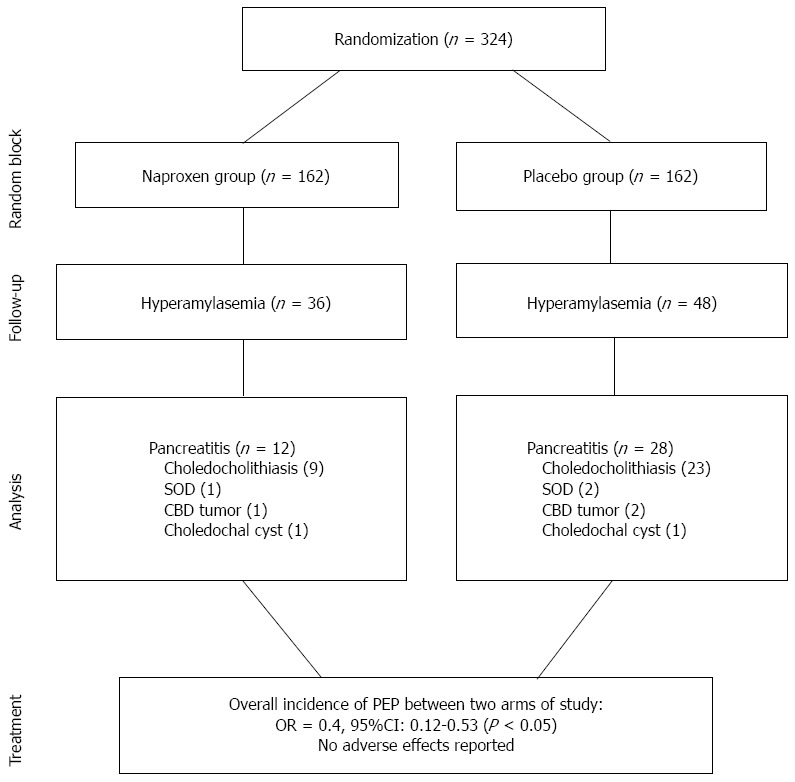

The most common final diagnosis after ERCP was choledocholithiasis, followed by several cases of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, common bile duct tumors, and choledochal cysts (Figure 1). We did use pancreatic duct stenting in the nobody of study subjects. All patients were discharged in good health and there were no reported side effects.

Figure 1.

Participant selection. CBD: Common bile duct; PEP: Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis; SOD: Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

DISCUSSION

A systematic review of five clinical trials[39], as well as two subsequent meta-analyses[40,41], indicate that administration of NSAIDs significantly decreases the incidence of PEP. Our findings show that a single dose of suppository naproxen given immediately before ERCP significantly reduces the overall incidence and severity of PEP. Elmunzer et al[42] in a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial showed post-ERCP pancreatitis developed in 16.9% of placebo group vs 9.2% in the indomethacin group, as well as, indomethacin decrease the incidence of moderate to severe PEP. Andrade-Dávila et al[43] conducted a controlled clinical trial where patients at least one major and/or two minor risk factors for developing post-ERCP pancreatitis. They suggested rectal indomethacin reduced the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis among patients at high risk of developing this complication. In our randomized controlled trial, the number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one episode of pancreatitis was 10. Sethi et al[44] in a meta analysis concluded rectal NSAIDs can decrease PEP with 11 patients needed to treatment. However, another meta-analysis showed the number needed to treat was 17[30]. On the other hand, recent controlled clinical trial a number needed to treat of 6.5 patients were calculated to prevent an episode of post-ERCP pancreatitis[43].

The occurrence of PEP varies according to patient characteristics and the type of intervention performed. We found that pancreatic duct injection, duration of ERCP (> 40 min), female sex and age (< 40 year) were significant risk factors for developing PEP, consistent with other studies[9,14,25,42]. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline presented cannulation attempts duration > 10 min and younger age increase the incidence of PEP[29]. Similarly, Sotoudehmanesh et al[14] demonstrated the protective effect of indomethacin for PEP in the patients with pancreatic duct injection. Furthermore, Elmunzer et al[42] showed that indomethacin significantly reduced the risk of moderate to severe PEP from 16.1% to 9.7% in patients with pancreatic injections. In our study, the risk of PEP was not associated with undergoing sphincterotomy, having sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. These findings are in contrast to those of Murray et al[13] who found that diclofenac was protective in patients who had sphincterotomy and those without sphincter of Oddi hypertension. Furthermore, recent guideline updated in 2014[29], female gender presented as a risk factor for PEP. In parallel our study, in recent controlled clinical trial, Suspected sphincter dysfunction oddi were not risk factor for PEP[43]. Till now, several meta-analyses[3,30,39-41,45] conclude that NSAIDs used in the different routes of administration decrease the incidence of pancreatitis and severity of pancreatitis. Although, the results of our study are relevant because the drug was rectally administrated immediately before procedure, the main difference between our study and those previously reported was the use of naproxen instead of indomethacin or diclofenac. Hence, to support the conclusion, a high-quality multicenter randomized clinical trial is required to better describe the effectiveness of naproxen as a NSAID.

In conclusion, a single-dose prophylactic naproxen suppository significantly decreases the occurrence and severity of PEP, particularly in those with pancreatic duct injections, multiple pancreatic duct cannulation attempts, those younger than 40 years of age, and requiring a procedure lasting more than 40 min. Moreover, this treatment produced no adverse events, consistent with previous works[10,28,40], and should therefore be administered immediately before ERCP procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center personnel.

COMMENTS

Background

Acute pancreatitis is the most feared complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) because it has the greatest potential for causing prolonged hospitalization, major morbidity, and occasionally death.

Research frontiers

Acute pancreatitis is the most common complication of ERCP; prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) has become more challenging.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Prevention of PEP has become more challenging. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) is effective in this condition but selection the best effective drug is required more examination of it. This study is based on this real.

Applications

This study evaluated the efficacy of rectally administered Naproxen for the prevention of PEP in patients received a single dose of naproxen or a placebo immediately before ERCP.

Peer-review

This study provides useful information for prevention of PEP. The authors show that a single dose of suppository naproxen administered immediately before ERCP reduces the incidence and severity of PEP.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center of Guilan University of Medical Science.

Clinical trial registration statement: This study is registered at Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials. The registration identification number is IRCT201105301155N14.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None declared.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 27, 2015

First decision: October 15, 2015

Article in press: January 18, 2016

P- Reviewer: Gonzalez-Ojeda A, Li SD, Lorenzo-Zuniga V S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Rabenstein T, Hahn EG. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: new momentum. Endoscopy. 2002;34:325–329. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman ML, Guda NM. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:845–864. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi N, Deng L, Altaf K, Huang W, Xue P, Xia Q. Rectal indomethacin for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:236–240. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.6000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshihara T, Horimoto M, Kitamura T, Osugi N, Ikezoe T, Kotani K, Sanada T, Higashi C, Yamaguchi D, Ota M, et al. 25 mg versus 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in Japanese patients: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006950. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochar B, Akshintala VS, Afghani E, Elmunzer BJ, Kim KJ, Lennon AM, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review by using randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143–149.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, Wong RC, Ferrari AP, Montes H, Roston AD, Slivka A, Lichtenstein DR, Ruymann FW, et al. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652–656. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A, et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheon YK, Cho KB, Watkins JL, McHenry L, Fogel EL, Sherman S, Schmidt S, Lazzell-Pannell L, Lehman GA. Efficacy of diclofenac in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in predominantly high-risk patients: a randomized double-blind prospective trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1126–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pezzilli R, Romboli E, Campana D, Corinaldesi R. Mechanisms involved in the onset of post-ERCP pancreatitis. JOP. 2002;3:162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li ZS, Pan X, Zhang WJ, Gong B, Zhi FC, Guo XG, Li PM, Fan ZN, Sun WS, Shen YZ, et al. Effect of octreotide administration in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia: A multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray B, Carter R, Imrie C, Evans S, O’Suilleabhain C. Diclofenac reduces the incidence of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sotoudehmanesh R, Khatibian M, Kolahdoozan S, Ainechi S, Malboosbaf R, Nouraie M. Indomethacin may reduce the incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis after ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:978–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumot JA, Conwell DL, Zuccaro G, Vargo JJ, Shay SS, Easley KA, Ponsky JL. A randomized, double blind study of interleukin 10 for the prevention of ERCP-induced pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2098–2102. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devière J, Le Moine O, Van Laethem JL, Eisendrath P, Ghilain A, Severs N, Cohard M. Interleukin 10 reduces the incidence of pancreatitis after therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:498–505. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manes G, Ardizzone S, Lombardi G, Uomo G, Pieramico O, Porro GB. Efficacy of postprocedure administration of gabexate mesylate in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:982–987. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andriulli A, Clemente R, Solmi L, Terruzzi V, Suriani R, Sigillito A, Leandro G, Leo P, De Maio G, Perri F. Gabexate or somatostatin administration before ERCP in patients at high risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:488–495. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andriulli A, Solmi L, Loperfido S, Leo P, Festa V, Belmonte A, Spirito F, Silla M, Forte G, Terruzzi V, et al. Prophylaxis of ERCP-related pancreatitis: a randomized, controlled trial of somatostatin and gabexate mesylate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:713–718. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andriulli A, Leandro G, Niro G, Mangia A, Festa V, Gambassi G, Villani MR, Facciorusso D, Conoscitore P, Spirito F, et al. Pharmacologic treatment can prevent pancreatic injury after ERCP: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arvanitidis D, Anagnostopoulos GK, Giannopoulos D, Pantes A, Agaritsi R, Margantinis G, Tsiakos S, Sakorafas G, Kostopoulos P. Can somatostatin prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:278–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messmann H, Vogt W, Holstege A, Lock G, Heinisch A, von Fürstenberg A, Leser HG, Zirngibl H, Schölmerich J. Post-ERP pancreatitis as a model for cytokine induced acute phase response in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1997;40:80–85. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abid GH, Siriwardana HP, Holt A, Ammori BJ. Mild ERCP-induced and non-ERCP-related acute pancreatitis: two distinct clinical entities? J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:146–151. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1979-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross V, Leser HG, Heinisch A, Schölmerich J. Inflammatory mediators and cytokines--new aspects of the pathophysiology and assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis? Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425–434. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilbao MK, Dotter CT, Lee TG, Katon RM. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). A study of 10,000 cases. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barthet M, Lesavre N, Desjeux A, Gasmi M, Berthezene P, Berdah S, Viviand X, Grimaud JC. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy: results from a single tertiary referral center. Endoscopy. 2002;34:991–997. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoshbaten M, Khorram H, Madad L, Ehsani Ardakani MJ, Farzin H, Zali MR. Role of diclofenac in reducing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e11–e16. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, et al. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799–815. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding X, Chen M, Huang S, Zhang S, Zou X. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1152–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elmi F, Rossi F, Lim JK, Aslanian HR, Siddiqui UD, Gorelick FS, Drumm H, Jamidar PA. M1477: A Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized, Double Blinded Controlled Study to Determine Whether a Single Dose of Intraduodenal Indomethacin Can Decrease the Incidence and Severity of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:AB232. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun HL, Han B, Zhai HP, Cheng XH, Ma K. Rectal NSAIDs for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surgeon. 2014;12:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad D, Lopez KT, Esmadi MA, Oroszi G, Matteson-Kome ML, Choudhary A, Bechtold ML. The effect of indomethacin in the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2014;43:338–342. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montaño Loza A, Rodríguez Lomelí X, García Correa JE, Dávalos Cobián C, Cervantes Guevara G, Medrano Muñoz F, Fuentes Orozco C, González Ojeda A. [Effect of the administration of rectal indomethacin on amylase serum levels after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and its impact on the development of secondary pancreatitis episodes] Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:330–336. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082007000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah T, Zfass A, Schubert ML. Chemoprevention of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis with Rectal NSAIDs: Does Poking Both Ends Justify the Means? Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2863–2864. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lua GW, Muthukaruppan R, Menon J. Can Rectal Diclofenac Prevent Post Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis? Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3118–3123. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wurm S, Schreiber F, Spindelboeck W. Mefenamic acid: A possible cause of drug-induced acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2015;15:570–572. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung SC, Hung SR, Lin CL, Lai SW, Hung HC. Use of celecoxib correlates with increased relative risk of acute pancreatitis: a case-control study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1490–1496. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pezzilli R, Morselli-Labate AM, Corinaldesi R. NSAIDs and acute pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:558–571. doi: 10.3390/ph3030558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dai HF, Wang XW, Zhao K. Role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Elta GH, Taylor JR, Fehmi SM, Higgins PD. A meta-analysis of rectal NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gut. 2008;57:1262–1267. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.140756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrade-Dávila VF, Chávez-Tostado M, Dávalos-Cobián C, García-Correa J, Montaño-Loza A, Fuentes-Orozco C, Macías-Amezcua MD, García-Rentería J, Rendón-Félix J, Cortés-Lares JA, et al. Rectal indomethacin versus placebo to reduce the incidence of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: results of a controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:85. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sethi S, Sethi N, Wadhwa V, Garud S, Brown A. A meta-analysis on the role of rectal diclofenac and indomethacin in the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2014;43:190–197. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng MH, Xia HH, Chen YP. Rectal administration of NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a complementary meta-analysis. Gut. 2008;57:1632–1633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]