Abstract

Background

Apoptosis of endothelial cells caused by reactive oxygen species plays an important role in ischemia/reperfusion injury after cerebral infarction. Buyang Huanwu Decoction (BYHWD) has been used to treat stroke and stroke-induced disability, however, the mechanism for this treatment remains unknown. In this study, we investigated whether BYHWD can protect human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) from H2O2-induced apoptosis and explored the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

To investigate the effect of BYHWD on the apoptosis of HUVECs, we established a H2O2-induced oxidative stress model and detected apoptosis by Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide staining. JC-1 and DCFH-DA assays,western blotting and electron microscopy were used to examine the mechanism of BYHWD on apoptosis.

Results

Pretreatment with BYHWD significantly inhibited H2O2-induced apoptosis and protein caspase-3 expression in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, BYHWD reduced reactive oxygen species production and promoted endogenous antioxidant defenses. Furthermore, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and structural disruption of mitochondria were both rescued by BYHWD.

Conclusions

BYHWD protects HUVECs from H2O2-induced apoptosis by inhibiting oxidative stress damage and mitochondrial dysfunction. These findings indicate that BYHWD is a promising treatment for cerebral ischemia diseases.

Keywords: Buyang Huanwu Decoction, Reactive oxygen species, Apoptosis, Ritochondria, Cerebral ischeima

Background

Stroke is the second leading cause of death and a major cause of disability worldwide. About 85–90 % of strokes are caused by ischemia (resulting from arterial occlusion) [1]. Excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2, superoxide radicals, and hydroxyl radicals has been observed during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) [2, 3]. This elevated ROS production alters mitochondrial permeability, which reduces mitochondrial membrane potentials (MMP), causing the release of Cyt-c. This activates caspase signaling pathways, which are important mediators of apoptosis [4–6]. Therefore, excessive ROS levels induce mitochondrial dysfunction, which promotes ROS-mediated apoptosis [7]. Preliminary studies have shown that ROS-induced apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells aggravates secondary brain injury after cerebral infarction [8, 9]. Protecting vascular endothelial cells against ROS-induced apoptosis may therefore have a therapeutic benefit in cerebrovascular diseases.

Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated that BYHWD improves the outcomes of ischemic stroke [10]. Recent studies have reported neuroprotective effects of BYHWD against cerebral I/R injury in animal experiments [11, 12]. BYHWD may also inhibit the apoptosis of nerve cells caused by I/R injury [13]. However, the mechanism behind the anti-apoptotic activity of BYHWD in endothelial cells is not well defined. Our previous findings have indicated that BYHWD is involved in angiogenesis by enhancing angiopoietin-1 expression after focal cerebral ischemia in rats [14]. In this study, we investigated the protective effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and explored the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Composition and preparation of BYHWD

BYHWD was prepared with the following components: Radix Astragali (Shanxi, China), Radix Angelicae Sinensis (Gansu, China), Radix Paeoniae Rubra (Sichuan, China), Rhizoma Ligustici Chuanxiong (Sichuan, China), Semen Persicae (Sichuan, China), Flos Carthami (Henan, China), and Pheretima (Guangdong, China). These components were mixed at a ratio of 120:10:10:10:10:10:4.5 (dry weight) [13]. All ingredients were purchased from the East China Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., Zhejiang Province, China, and deposited at the Department of Pharmacy, Zhejiang University after verification by Professor Dong at the same institute. The decoction was made by boiling the mixture in ten times the amount of distilled water at 100 °C for 30 min. Then, the drug solution was poured out for use and the residue boiled two more times. The total drug solution for three times was vacuum-cooled and dried to a powder, which was dissolved in distilled water at a final concentration of 2.0 g/ml (equivalent to the dry weight of the raw materials).

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of active ingredients

Based on the theories of traditional Chinese medicine, a herbal formulation contains more than one Chinese herb. According to the literature, the effective components of BYHWD are astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, amygdalin, and tetramethylpyrazine. These active ingredients were quality controlled by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in our study [15]. Standard chemicals including astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, amygdalin, and tetramethylpyrazine were purchased from the Biological Products Analysis Bureau at the Ministry of Public Health of China. Briefly, HPLC profiling was performed using an Agilent 1100 series equipped with a quaternary solvent delivery system, auto-sampler, and a photodiode array (PDA) detector (Waters Breeze, USA). Separation was performed on a Cosmosil ARII column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; temperature: 35 °C; flowrate: 1 ml/min; injection volume: 10 μL). The mobile phase used astragaloside IV, acetonitrile/water (33/67, v:v), paeoniflorin, amygdalin, tetramethylpyrazine, and a methanol/water (33/67, v:v) solution. The linear gradient elution was optimized for BYHWD as follows: 2–2 % B (0–5 min), 2–30 % B (5–50 min), 30–60 % B (50–70 min), with a 15-min re-equilibration of the gradient elution.

Cell culture

HUVECs were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA) and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Hangzhou Sijiqing Biological Engineering Materials Co., Ltd., China) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hangzhou Sijiqing Biological Engineering Materials Co., Ltd., China), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were used at passage 4–6 in all experiments.

MTT assay

An MTT assay was used to estimate cell viability. Briefly, HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates (BD Falcon, USA), at a density of 2 × 103 cells/well in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS. One day after plating, the cells were washed and incubated in serum-free medium for 12 h. The cells were then washed again. To explore the cytotoxicity of BYHWD on HUVECs, cells were incubated with various concentrations of BYHWD (5–45 mg/ml) for 24 h. To explore the effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, cells were pretreated for 6 h with culture medium containing different concentrations of BYHWD (5, 15, and 30 mg/ml). The cells were then exposed to H2O2 (320 μmol/l) diluted in culture medium for 6 h. After H2O2 exposure, the culture supernatant was removed and cells were washed with PBS before incubating in 150 μl MTT solution (5 mg/ml) in culture medium at 37 °C for 3 h. After removal of the MTT solution, the colored formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μl DMSO. Plates were gently shaken for 10 min before measuring the optical density at 490 nm using an enzyme-labeled instrument (Biotek ELX 800/FLX800).

Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI) staining

Apoptotic HUVECs were identified by Hoechst 33342 and PI (Hangzhou Baoke Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China) staining. Briefly, HUVECs were seeded in a 6-well plate (BD Falcon, USA) at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS. One day after plating, the cells were washed and incubated in serum-free medium for 12 h. The cells were then washed again and pretreated for 6 h with different concentrations of BYHWD (5, 15, and 30 mg/ml). The cells were then exposed to H2O2 (320 μmol/l) for 6 h before double-staining with Hoechst 33342 and then PI for 10 min each at 37 °C according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). Hoechst 33342 was excited at 361 nm and emitted blue fluorescence at 460 nm. PI was excited at 480 nm and red fluorescence was detected at 610 nm. Data were analyzed using Image Pro plus software (Media Cybernetics). Data were expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells.

Western blotting

After incubating as described above, cells were seeded into 6-well plates. Cells were lysed in 200 μl RIPA lysis buffer (Hangzhou Baoke Biological Engineering Materials Co., Ltd., China), centrifuged at 20,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. Nuclear extracts were collected according to the protocol of the nuclear extraction kit (Hangzhou Baoke Biological Engineering Materials Co., Ltd., China). Protein extracts were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Hangzhou Baoke Biological Engineering Materials Co., Ltd., China). Equal amounts of proteins (50 μg per lane) were separated on a 10 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5 % fat-free milk at room temperature for 2 h and incubated with primary antibodies against active caspase-3 (Abcam, USA, 1:1000) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 1:1000) at 4 °C overnight. After primary antibody incubation, membranes were washed three times in TBST then incubated in secondary antibody solutions for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the signals were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence and X-ray film (Kodak, USA). Protein levels were quantified by densitometry. Data were expressed as the ratio of active caspase-3 to GAPDH.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Measurement of intracellular ROS was based on ROS-mediated conversion of non-fluorescent 2,7-DCFH-DA into fluorescent DCFH. Briefly, HUVECs were seeded into a 6-well plate (BD Falcon, USA) at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS. One day after plating, the cells were washed and incubated in serum-free medium for 12 h. The cells were washed and pretreated with BYHWD (30 mg/ml) for 6 h. The cells were then exposed to H2O2 (320 μmol/l) for 6 h before incubating in 2,7-DCFH-DA (Sigma, USA, 5 μM) in PBS for 30 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS then the DCFH fluorescence from each well was excited at 485 nm and the emission was measured at 520 nm by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan). For spectrofluorophotometry analysis, the cells were collected and analyzed. The fluorescence of DCFH was detected using a spectrofluorophotometer (Amersham Biosciences, USA). Data were expressed relative to the mean sham value.

Measurement of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels

The levels of SOD and MDA were determined using commercially available kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Materials Co., Ltd., China). Briefly, after incubating as described above, cells were lysed and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, to collect the supernatant. The SOD and MDA levels in the supernatant were measured according to the kit protocol and analyzed on a spectrophotometer,The absorbance was read at 550 nm (SOD) and 450 nm (MDA). The levels were calculated using a standard calibration curve and expressed in U/mg (SOD) and nmol/ml (MDA). Data were expressed as relative to the mean sham value.

Transmission electron microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed to examine the morphology of the mitochondria in HUVECs. Briefly, after incubating as described above, cells were collected and prefixed with 2.5 % w/v glutaraldehyde for 2 h, rinsed three times in 0.1 mol/l PBS (pH 7.4), and post-fixed for 2 h in 1 % w/v osmium tetroxide at −4 °C. The fixed cells were dehydrated through an ethanol series then completely dehydrated in absolute ethanol. Cells were detached using propylene oxide and infiltrated with Spurr low-viscosity embedding medium (Wuhan Boshide Biological Technology Co., Wuhan, China). Sections were cut using an ultramicrotome with a diamond knife, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Cells were observed using a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1230, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of MMP

MPP was assessed using the lipophilic cationic probe JC-1, which is a sensitive fluorescent dye (Invitrogen, USA). Briefly, after incubating as described above, cells were incubated with 5 mM JC-1 dye (Molecular Probes) at 37 °C for 15 min. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and immediately analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). Red emission indicated membrane potential-dependent JC-1 aggregates in the mitochondria. Green fluorescence indicated the monomeric form of JC-1 entering the cytoplasm after mitochondrial membrane depolarization. The ratio of red to green fluorescence intensity was measured and data were expressed as relative to the mean sham value.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test and ANOVA. Significance was accepted at P<0.05. SPSS 19.0 software was used for statistical analysis.

Results

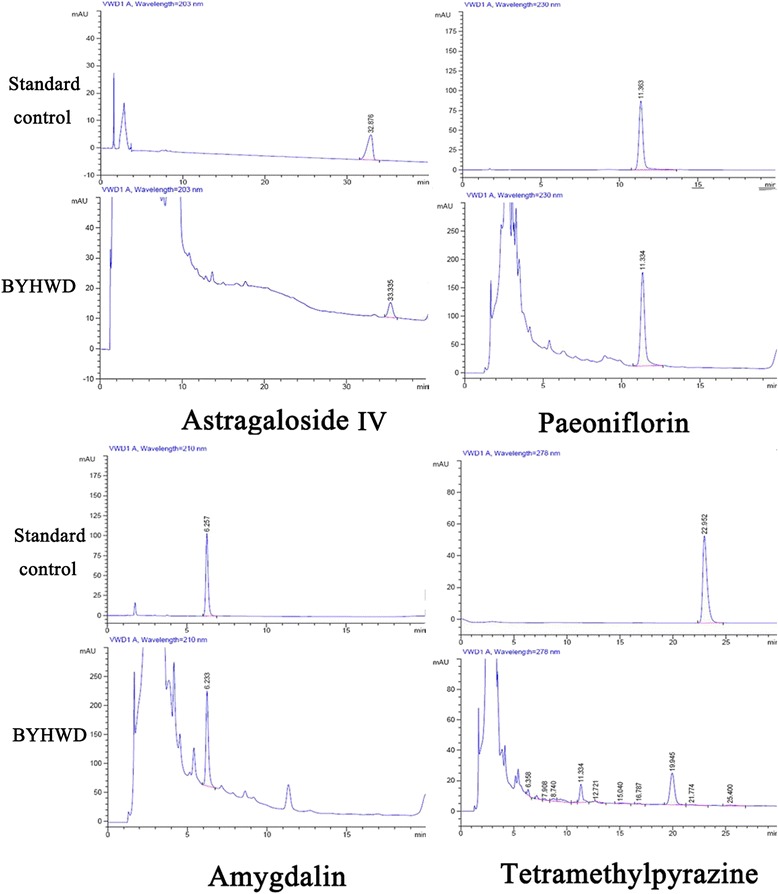

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of BYHWD components

To identify BYHWD extracts containing active ingredients, quality control was performed by HPLC. BYHWD contained astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, and amygdalin, but not tetramethylpyrazine (Fig. 1). The summit retention time of astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, and amygdalin was approximately 35 min, 11.5 min, and 6 min, respectively. The content of astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, and amygdalin was 0.58, 1.63, and 1.82 mg/g, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Representative HPLC chromatograms of active BYHWD components and standard controls. BYHWD contains astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, and amygdalin, but not tetramethylpyrazine. Summit retention times of astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, and amygdalin were 35 min, 11.5 min and 6 min, respectively

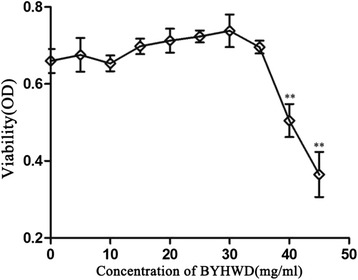

Cytoactivity and cytotoxicity of BYHWD in HUVECs

To determine the optimal experimental concentration of BYHWD, we measured the viability of HUVECs after treatment with various concentrations of BYHWD by MTT assay. Cytoactivity was not significantly increased by BYHWD at concentrations of 5–30 mg/ml, but cytotoxicity increased in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations of 35–45 mg/ml (Fig. 2). To investigate whether effects of BYHWD were dose-dependent, we selected low (5 mg/ml), medium (15 mg/ml) and high (30 mg/ml) doses for experiments.

Fig. 2.

Cytoactivity and cytotoxicity of HUVECs treated with various concentrations of BYHWD. HUVEC viability after treatment with different concentrations of BYHWD (5–45 mg/ml) for 24 h. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 6).** P < 0.01, compared to sham group

BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in HUVECs

To evaluate the effect of BYHWD on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in HUVECs, we measured the viability of BYHWD-treated HUVECs by MTT assay. BYHWD significantly increased cell viability in a dose-dependent manner after H2O2-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 3). These results suggest that BYHWD protects HUVECs from H2O2-induced injury.

Fig. 3.

Protective effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced viability loss in HUVECs. Quantitative analysis of the effect of BYHWD on H2O2-induced viability loss in HUVECs. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 6).** P < 0.01, compared to sham group. ## P < 0.01, compared to H2O2 group (320 μmol/l)

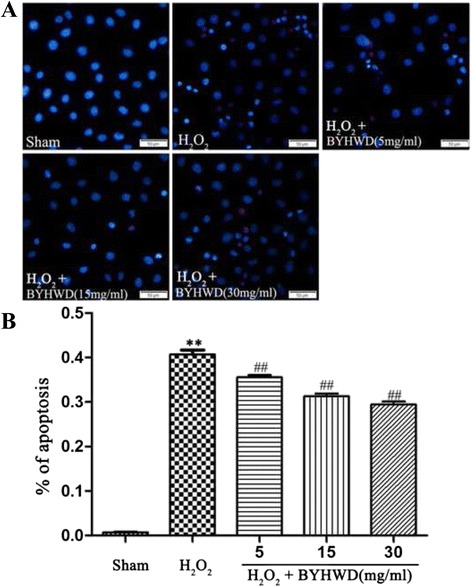

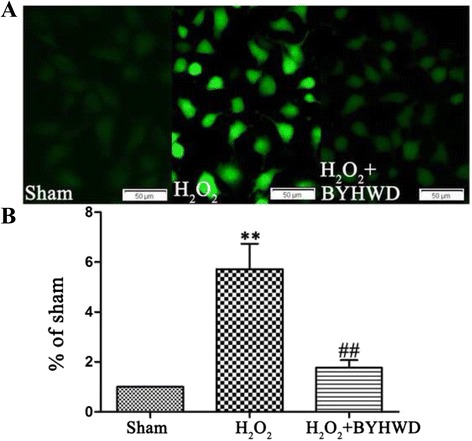

BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs

To evaluate the effect of BYHWD on H2O2-induced apoptosis, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and PI. Cell nuclei condensed into a bright blue was defined as strongly expressing Hoechst 33342, nornal nuclei with common blue defined as expressing Hoechst 33342. The changes in cell nuclei of apoptotic cells were defined by Hoechst 33342 staining as described previously [16]. Cells expressing Hoechst 33342 and not expressing PI were considered unstressed. Cells strongly expressing Hoechst 33342 and not expressing PI were considered early apoptotic cells. Cells strongly expressing Hoechst 33342 and expressing PI were classified as late apoptotic cells. Cells expressing Hoechst 33342 and strongly expressing PI were considered dead. Exposure to H2O2 increased apoptosis (Fig. 4) and treatment with BYHWD significantly reduced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). This suggests that BYHWD may block an apoptotic pathway.

Fig. 4.

Effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs. a Apoptotic cells were observed using a fluorescence microscope by Hoechst 33342 and PI staining in HUVECs. b Quantitative data showed the percentage of apoptotic cells according to treatment in HUVECs. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 10). ** P < 0.01, compared to sham group. ## P < 0.01, compared to H2O2 group (320 μmol/l)

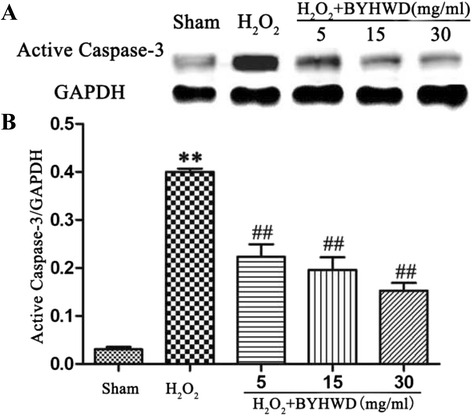

BYHWD decreases H2O2-induced caspase-3 expression

H2O2-induced caspase-3 cleavage is known to regulate cell apoptosis [6]. To determine whether BYHWD affects this process, we measured caspase-3 expression by western blot. Exposure to H2O2 significantly increased caspase-3 expression (Fig. 5) and BYHWD treatment significantly reduced caspase-3 expression in a dose-dependent manner. These results further verify that BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

Effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced caspase-3 expression in HUVECs. a Caspase-3 protein expression in HUVECs were examined by western blotting. b Quantitative analysis of band densities for caspase-3 expression in HUVECs were measured. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). ** P < 0.01, compared to sham group. ## P < 0.01, compared to H2O2 group (320 μmol/l)

BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced ROS production

Exogenous addition of H2O2 induces intracellular ROS production, which affects cell metabolism [17]. To investigate whether inhibition of apoptosis by BYHWD is related to the intracellular production of ROS, we measured intracellular ROS levels using fluorescence microscopy and spectrofluorophotometry with DCFH-DA. DCFH-DA is cleaved intracellularly by esterases and subsequently oxidized to DCFH by ROS. Green fluorescence produced by DCFH indicates abnormally high ROS levels. Exposure to H2O2 (320 μmol/l) induced a burst of green fluorescence in HUVECs (Fig. 6), which was inhibited by BYHWD. These findings suggest that BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced ROS production.

Fig. 6.

Effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced intracellular ROS levels in HUVECs. a Representative images of intracellular ROS in HUVECs by fluorescence microscopy.b Quantitative analysis of intracellular ROS in HUVECs by spectrofluorophotometry. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 10). ** P < 0.01, compared to sham group. ## P < 0.01, compared to H2O2 group (320 μmol/l)

BYHWD decreased MDA levels and increased SOD levels induced by H2O2

MDA levels reflect the degree of lipid peroxidation by ROS-induced cell damage and SOD activity indirectly reflects the ability to eliminate ROS [18]. To determine whether BYHWD affects ROS-induced cell damage, we examined intracellular MDA and SOD levels. Exposure to H2O2 reduced MDA and increased SOD levels and treatment with BYHWD reduced MDA and further increased SOD levels (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effects of BYHWD on H2O2-induced MDA and SOD levels in HUVECs. a Quantitative analysis of intracellular MDA levels in HUVECs. b Quantitative analysis of intracellular SOD levels in HUVECs. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 10). ** P < 0.01, compared to sham group. ## P < 0.01, compared to H2O2 group (320 μmol/l)

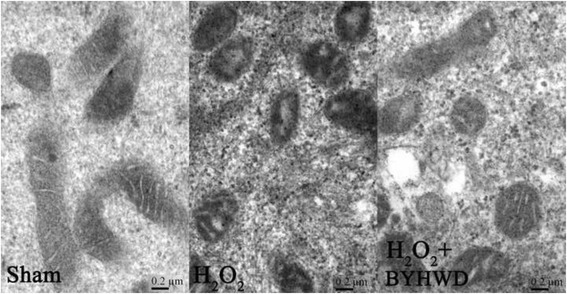

BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced ultrastructural disruption of mitochondria

Mitochondria are important organelles for cellular energy production and are involved in cell apoptosis [19]. To demonstrate whether inhibition of apoptosis by BYHWD is related to changes in mitochondria ultrastructure, we examined HUVECs by transmission electron microscopy. H2O2 caused mitochondrial swelling, disrupted the mitochondrial membrane, and fragmented the mitochondrial cristae in HUVECs (Fig. 8). Mitochondrial disruption by H2O2 was rescued in HUVECs by BYHWD treatment (30 mg/ml). Therefore, BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced ultrastructural disruption of HUVEC mitochondria.

Fig. 8.

BYHWD inhibits H2O2-induced ultrastructural disruption of mitochondria in HUVECs. Transmission electron micrographs showed swelling mitochondria, disrupted the mitochondrial membrane, and fragmented the mitochondrial cristae induced by H2O2 (320 μmol/l) (a and b). Mitochondrial disruption was rescued by BYHWD treatment (30 mg/ml) (c)

BYHWD restores H2O2-induced reduction of MMP

Opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores by ROS causes mitochondrial dysfunction because of mitochondrial matrix swelling and outer membrane rupture [20]. To examine this, we measured MMP in HUVECs using JC-1. High MMP is indicated by the production of red fluorescence and depolarized regions are indicated by green fluorescence. Exposure to H2O2 reduced the production red fluorescence and increased the intensity of green fluorescence (Fig. 9). BYHWD treatment increased the production of red fluorescence and reduced the production of green fluorescence, demonstrating that BYHWD can restore H2O2-induced loss of MPP.

Fig. 9.

BYHWD restores H2O2-induced reduction of MMP in HUVECs. a Representative images of MMP in HUVECs measured by JC-1. b Quantitative analysis of MMP in HUVECs. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 9). ** P < 0.01, compared to sham group. ## P < 0.01, compared to H2O2 group (320 μmol/l)

Discussion

Vascular endothelial cells maintain vascular permeability and vascular responses to a variety of physiological and pathological stimuli [21]. When the structure and function of vascular endothelial cells are impaired, lesions form in the lumen (e.g. thrombosis, atherosclerosis and vasculitis), causing vascular stenosis or occlusion [20]. If this occurs in cerebral vessels, it can cause ischemic cerebrovascular disease, such as transient ischemic attack and cerebral infarction [22]. Endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis are important for neurological recovery after cerebral infarction [23]. However, excessive ROS production aggravates endothelial cell injury during cerebral I/R [24, 25]; endothelial cells produce many ROS, which reduces antioxidant activity and sensitivity to exogenous ROS [26]. Neurons also produce ROS, which increases the damage done to endothelial cells by oxygen-free radicals [27]. Preliminary studies have shown that ROS-induced oxidative stress induces lipid peroxidation and protein damage in membranes, alters the antioxidant system, mutates DNA, alters gene expression, and induces vascular endothelial cell apoptosis, thereby aggravating brain ischemia and hypoxia [28]. Protecting vascular endothelial cells from ROS-induced apoptosis may help the treatment of cerebrovascular diseases. HUVECs are the most commonly used model in cardio-cerebrovascular disease research [20, 29]. For this reason, we selected H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs as an in vitro model of endothelial cell oxidative stress damage after cerebral ischemia.

BYHWD is one of the most classical medicinal prescriptions, comprised of seven active ingredients: Radix Astragali, Radix Angelicae Sinensis, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Rhizoma Ligustici Chuanxiong, Semen Persicae, Flos Carthami, and Pheretima [13]. Based on the theories of traditional Chinese medicine, the combined effects of multiple herbs within a formula may have a powerfully curative effect. A traditional herbal formulation such as BYHWD is prescribed according to the principles of monarch, minister, assistant and guide. The monarch Radix Astragali is the chief drug for treating the disease, the minister Radix Angelicae Sinensis intensifies the effect of the monarch drug, the assistants Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Semen Persicae, and Flos Carthami treat the secondary symptoms or inhibit the toxicity of the monarch drug, and the guide drug Pheretima guides the herbs to the diseased regions and balances the effects of all herbs. Chemical investigations have revealed that the active constituents of BYHWD are numerous and diverse. Radix Astragali contains flavonoids (formononetin, ononin, calycosin and its glycoside), saponins (astragaloside I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII), polysaccharides and amino acid; Radix Angelicae Sinensis contains ferulic acid; Radix Paeoniae Rubra contains paeoniflorin, oxypaeoniflorin, benzoylpaeoniflorin and ligustilide; Rhizoma Ligustici Chuanxiong contains tetramethylpyrazine, perlolyrine, ligustilide, ferulic acid, and protocatechuic acid; Semen Persicae contains amygdalin, prunasin, sterol, and organic acid; Flos Carthami contains hydroxysafflor yellow A; and Pheretima contains hypoxanthine [15, 30]. Pharmacological studies also have revealed that the active components of BYHWD contains calycosin-O-β-D-glucoside, formononetin, ononin, calycosin, astragaloside IV and astragaloside I from Radix Astragali, paeoniflorin from Radix Paeoniae Rubra, tetramethylpyrazine, ferulic acid and ligustilide from Radix Angelicae Sinensis and Rhizoma Ligustici Chuanxiong, amygdalin from Semen Persicae, hydroxysafflor yellow A and kaempferol from Flos Carthami [30–32].

BYHWD has been used to treat stroke and stroke-induced disability in China for centuries [33]. Recent studies have reported that BYHWD has a protective effect on nerve cells in humans and animal models [12, 34]. BYHWD exerts its neuroprotective effects by promoting the growth and differentiation of nerve cells [20, 35], and inhibiting neural apoptosis and inflammation after cerebral infarction [36]. However, the protective mechanisms of BYHWD in endothelial cells after brain ischemia are currently undefined. To address this, we explored the protective effects and mechanisms of BYHWD on H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs.

H2O2 exposure induced apoptosis, cytoactivity, ROS increase, and mitochondrial disorder in HUVECs. BYHWD inhibited H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs by reducing intracellular levels of ROS and MDA. In addition, BYHWD increased intracellular SOD levels and restored the MMP and ultrastructural integrity of mitochondria. We have demonstrated for the first time that BYHWD protects against H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs by inhibiting a ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction pathway. These findings may help to identify novel drug targets and therapies for cerebrovascular diseases.

Apoptosis is a process of programmed cell death in which defective and harmful cells are eliminated to maintain homeostasis [37]. There are three pathways involved in apoptosis: the mitochondrial pathway, death receptor pathway, and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway [38]. Mitochondria are key regulators of cellular energy homeostasis and play a central role in apoptosis [39]. Mitochondrial apoptotic signals decrease the MMP, causing Cyt-c and Smac and other contents to leak from the mitochondria [4, 5]. Smac speeds up apoptosis and Cyt-c promotes apoptosis by activating caspase-3 [4, 6]. We have shown that H2O2 causes mitochondrial swelling, disruption of mitochondrial cristae, reduced MMP and activation of caspase-3 in HUVECs, eventually leading to apoptosis. BYHWD treatment reversed these effects and attenuated H2O2-induced apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway.

ROS are powerful oxidizing agents in cells and established regulators of apoptosis [40]. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial function are positively correlated. Oxidative stress can cause cellular apoptosis by mitochondria-dependent pathways [41]. H2O2 can cause endothelial cell injury by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction, including loss of MMP and the MMP transition, which increases the formation of ROS by inhibiting the respiratory chain [20, 29]. Excessive ROS cause peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and lipids, damaging membrane fluidity, permeability and integrity. MDA levels reflect the degree of lipid peroxidation and indirectly the degree of cell damage. SOD is a free-radical scavenger and SOD levels indirectly reflect the level of ROS elimination [18]. We observed that intracellular ROS and MDA levels increased and SOD levels decreased in HUVECs exposed to H2O2. BYHWD reduced ROS production in HUVECs, which increased the activity of SOD and reduced MDA levels, indicating that BYHWD has antioxidant effects. We propose that these effects represent the mechanism by which BYHWD inhibits H2O2-mediated apoptosis in HUVECs.

Conclusion

We have shown that BYHWD significantly attenuates H2O2-induced apoptosis in HUVECs. Furthermore, BYHWD inhibited intracellular ROS production, increased SOD activity, reduced MDA levels, reversed MMP decline and rescued structural disruption of mitochondria. These findings suggest that the anti-apoptotic mechanisms of BYHWD involve inhibiting ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction pathways in HUVECs.

Abbreviations

BYHWD, Buyang Huanwu Decoction; HUVECs, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; MMP, Mitochondrial membrane potential; (I/R), Cerebral ischemia/reperfusion; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, Malondialdehyde; PI, Propidium iodide.

Acknowledgments and funding

This work was supported by grants of National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81501065, no.81571147), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (no. LY16H090004), Zhejiang Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Plan (no.2016ZA115). Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan (no.2015KYA091).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available.

Authors’ contributions

JS, RYZ and JWP developed the idea and designed the research. JS, YZ and KYH wrote the manuscript, selected which studies to include and extracted the data from the studies, interpreted the analysis and drafted the final review. XXX and HJ obtained copies of the studies and revised the writing. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Soler EP, Ruiz VC. Epidemiology and risk factors of cerebral ischemia and ischemic heart diseases: similarities and differences. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6(3):138–49. doi: 10.2174/157340310791658785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahles T, Luedike P, Endres M, Galla HJ, Steinmetz H, Busse R, et al. NADPH oxidase plays a central role in blood–brain barrier damage in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(11):3000–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu Y, Li R, Yang H, Luo H, Chen Z. Sirtuin 6 is essential for sodium sulfide-mediated cytoprotective effect in ischemia/reperfusion-stimulated brain endothelial cells. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(3):601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paquette JC, Guérin PJ, Gauthier ER. Rapid induction of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by L-glutamine starvation. Cell Physiol. 2005;202(3):912–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Yu RY, He QY. Proteomic analysis of anticancer TCMs targeted at mitochondria. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:539260. doi: 10.1155/2015/539260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Tang Y, Qian Y, Chen R, Zhang L, Wo L, et al. Allicin prevents H2O2-induced apoptosis of HUVECs by inhibiting an oxidative stress pathway. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:321. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jendrach M, Mai S, Pohl S, Vöth M, Bereiter-Hahn J. Short-and long-term alterations of mitochondrial morphology, dynamics and mtDNA after transient oxidative stress. Mitochondrion. 2008;8(4):293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Tan Z, Tran ND. Chemical hypoxia-ischemia induces apoptosis in cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells. Brain Res. 2000;877(2):134–40. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02666-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun K, Fan J, Han J. Ameliorating effects of traditional Chinese medicine preparation, Chinese materia medica and active compounds on ischemia/reperfusion-induced cerebral microcirculatory disturbances and neuron damage. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5(1):8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao C, Wu F, Shen J, Lu L, Fu DL, Liao WJ, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of buyang huanwu decoction for acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:630124. doi: 10.1155/2012/630124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao LD, Wang JH, Jin GR, Zhao Y, Zhang HJ. Neuroprotective effect of Buyang Huanwu decoction against focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats–time window and mechanism. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(2):339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei RL, Teng HJ, Yin B, Xu Y, Du Y, He FP, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of buyang huanwu decoction in animal model of focal cerebral ischemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:138484. doi: 10.1155/2013/138484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang HW, Liou KT, Wang YH, Lu CK, Lin YL, Lee IJ, et al. Deciphering the neuroprotective mechanisms of Bu-yang Huan-wu decoction by an integrative neurofunctional and genomic approach in ischemic stroke mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138(1):22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen J, Zhu Y, Yu H, Fan ZX, Xiao F, Wu P, et al. Buyang Huanwu decoction increases angiopoietin-1 expression and promotes angiogenesis and functional outcome after focal cerebral ischemia. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2014;15(3):272–80. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1300166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Zhang W, Li H, Chen BY, Zhang GM, Tang YH, et al. Inhibition of aortic intimal hyperplasia and cell cycle protein and extracellular matrix protein expressions by BuYang HuanWu Decoction. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125(3):423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemarié A, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Morzadec C, Allain N, Fardel O, Vernhet L. Cadmium induces caspase-independent apoptosis in liver Hep3B cells: role for calcium in signaling oxidativestress-related impairment of mitochondria and relocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36(12):1517–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang YH, Sun W, Li W, Hu HZ, Zhou L, Jiang HH, et al. Calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside promotes oxidative stress-induced cytoskeleton reorganization through integrin-linked kinase signaling pathway in vascular endothelial cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:315. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0839-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Shen XC, Tao L, Li WK, Zhang YY, Luo H, Xia YY. Evidence-based antioxidant activity of the essential oil from Fructus A. zerumbet on cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells’ injury induced by ox-LDL. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:174. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa K, Takenaga K, Akimoto M, Koshikawa N, Yamaguchi A, Imanishi H, et al. ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis. Science. 2008;320:661–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1156906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong G, Qin Y, Huang W, Zhou S, Yang X, Li D. Rutin inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis through regulating reactive oxygen species mediated mitochondrial dysfunction pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;628(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugusman A, Zakaria Z, Hui CK, Nordin NA. Piper sarmentosum inhibits ICAM-1 and Nox4 gene expression in oxidative stress-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komotar RJ, Starke RM, Otten ML, Merkow MB, Garrett MC, Marshall RS, et al. The role of indirect extracranial-intracranial bypass in the treatment of symptomatic intracranial atheroocclusive disease. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(5):896–904. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS17658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishikawa H, Tajiri N, Shinozuka K, Vasconcellos J, Kaneko Y, Lee HJ, et al. Vasculogenesis in experimental stroke after human cerebral endothelial cell transplantation. Stroke. 2013;44(12):3473–81. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Gao A, Feng D, Wang Y, Zhang L, Cui Y, et al. Evaluation of the protective potential of brain microvascular endothelial cell autophagy on blood–brain barrier integrity during experimental cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5(5):618–26. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alluri H, Stagg HW, Wilson RL, Clayton RP, Sawant DA, Koneru M, et al. Reactive oxygen species-caspase-3 relationship in mediating blood–brain barrier endothelial cell hyperpermeability following oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation. Microcirculation. 2014;21(2):187–95. doi: 10.1111/micc.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen T, Guo Z, Jiao XY, Zhang YH, Li JY, Liu HJ. Protective effects of peoniflorin against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89(6):445–53. doi: 10.1139/y11-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim GW, Kondo T, Noshita N, Chan PH. Manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency exacerbates cerebral infarction after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in mice implications for the production and role of superoxide radicals. Stroke. 2002;33(3):809–15. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J, Li J, Lu J, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Wan H. Synergistic protective effect of astragaloside IV-tetramethylpyrazine against cerebral ischemic-reperfusion injuryinduced by transient focal ischemia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen YD, Wang H, Kho SH, Rinkiko S, Sheng X, Shen HM, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects HUVECs against hydrogen peroxide induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw LH, Lin LC, Tsai TH. HPLC-MS/MS analysis of traditional Chinese medical formulation of Bu-Yang-Huan-Wu-Tang and its pharmacokinetics after oral administration to rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu EH, Qi LW, Cheng XL, Peng YB, Li P. Simultaneous determination of twelve bioactive constituents in Buyang Huanwu decoction by HPLC-DAD-ELSD and HPLC-TOF/MS. Biomed Chromatogr. 2010;24(2):125–31. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Yang G, Lin R, Hu Z. Determination of paeoniflorin, calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, ononin, calycosin and formononetin in rat plasmaafter oral administration of Buyang Huanwu decoction for their pharmacokinetic study by liquidchromatography-mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2011;25(4):450–7. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li XM, Bai XC, Qin LN, Huang H, Xiao ZJ, Gao TM. Neuroprotective effects of Buyang Huanwu Decoction on neuronal injury in hippocampus after transient forebrain ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;346(1):29–32. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Gao K, Liu J, Zhao H, Wang J, Li Y, et al. A review of the pharmacological mechanism of traditional chinese medicine in the intervention of coronary heart disease and stroke. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2013;10(6):532–7. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i6.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai G, Liu B, Liu W, Tan X, Rong J, Chen X, et al. Buyang Huanwu Decoction can improve recovery of neurological function, reduce infarction volume, stimulate neural proliferation and modulate VEGF and Flk1 expressions in transient focal cerebral ischaemic rat brains. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113(2):292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin Y, Dong L, Wu C, Qin J, Li S, Wang C, et al. Buyang Huanwu Decoction fraction protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating the inflammatory response and cellular apoptosis. Neural Regen Res. 2013;8(3):197–207. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennetts PS, Pierce JD. Apoptosis: understanding programmed cell death for the CRNA. AANA J. 2010;78(3):237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanz AB, Santamaría B, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A. Mechanisms of renal apoptosis in health and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(9):1634–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peinado JR, Diaz-Ruiz A, Frühbeck G, Malagon MM. Mitochondria in metabolic disease: getting clues from proteomic studies. Proteomics. 2014;14(4–5):452–66. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Wang K, Lei Y, Li Q, Nice EC, Huang C. Redox signaling: Potential arbitrator of autophagy and apoptosis in therapeutic response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:452–65. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinha K, Das J, Pal PB, Sil PC. Oxidative stress: the mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87(7):1157–80. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available.