Abstract

Early investigations of guilt cast it as an emotion that prompts broad reparative behaviors that help guilty individuals feel better about themselves or about their transgressions. The current investigation found support for a more recent representation of guilt as an emotion designed to identify and correct specific social offenses. Across five experiments, guilt influenced behavior in a targeted and strategic way. Guilt prompted participants to share resources more generously with others, but only did so when those others were persons whom the participant had wronged and only when those wronged individuals could notice the gesture. Rather than trigger broad reparative behaviors that remediate one’s general reputation or self-perception, guilt triggers targeted behaviors intended to remediate specific social transgressions.

Keywords: guilt, judgment and decision making, emotions, relationships, generosity

Prompted by mistakes or bad behavior, guilt can trigger subsequent virtue. Guilt prompts people to exhibit constraint (Giner-Sorolla, 2001), to avoid self-indulgence (Zemack-Rugar, Bettman, & Fitzsimons, 2007), and to reduce prejudice (Amodio, Devine, & Harmon-Jones, 2007). However, precisely when guilty feelings encourage such virtuous actions and whom the virtuous actions are designed to please are not yet clearly understood.

At its core, guilt is an interpersonal emotion—it is one that is felt most commonly when one has wronged another person (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994; Tangney, 1992; Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, 2008). Consistent with a theory that interpersonal guilt arises from specific transgressions, we suggest that guilt’s effect on interpersonal behavior is targeted toward remediating relationships that were harmed by the guilt-inducing act. In particular, we suggest that guilt increases generosity toward others, but only toward recipients whom the guilty person has wronged and only when that person can notice the gesture. Rather than trigger broad behaviors that repair a general tarnished self-perception or reputation, interpersonal guilt appears to trigger behaviors intended to remediate specific social transgressions.

Guilt Is a Self-Conscious Emotion

Guilt is a member of a group of negative self-conscious emotion that includes shame, regret, and embarrassment (Lewis, 1993; Tracy & Robins, 2007). Self-conscious emotions are unique in the sense that they occur in response to a past behavior and rely on reflection on past actions for activation, causing them to be recognized more slowly than other affective states such as stress and boredom (Giner-Sorolla, 2001). In contrast to “basic emotions,” a select class of emotions that emerge early in life and have universally recognizable visual expressions (e.g., fear, anger, and happiness; Ekman, 1992), self-conscious emotions are considered “cognition dependent” (cf. Zemack-Rugar et al., 2007) and complex, requiring a high level of conscious self-awareness and self-representation (Tracy & Robins, 2007). These high levels of self-awareness are necessary for self-conscious emotions to occur because people must evaluate their own selves in comparison with an ideal standard for a self-conscious emotion to develop (Tracy & Robins, 2006).

Important distinctions between guilt and other negative self-conscious emotions exist. Regret occurs when a bad outcome is compared with a better outcome that could have resulted from different choices. In contrast, guilt occurs when a person feels responsible for a bad outcome that typically affected others (Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, 2008). Shame occurs when someone feels bad about oneself for committing a transgression. In contrast, guilt occurs when a person feels bad about the transgression itself (Tangney, 1996; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). These differences among the origins of self-conscious emotions suggest unique consequences for the emotion of guilt. For example, whereas shame should produce withdrawal from social situations or broad attempts to correct one’s status as a degraded person (de Hooge, Zeelenberg, & Breugelmans, 2007), we expect guilt to prompt precise attempts to correct past transgressions.

A hallmark feature of guilt is that it is unpleasant to experience. Guilt also is commonly viewed as a toxic emotion—one to be avoided at all costs. Self-help books promise to free people from the shackles of guilt (Carrell, 2007; Forward & Frazier, 1998; Jampolsky, 1985), and extreme guilt is considered to be an indicator of depression (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). At the same time that guilt commonly is perceived to be maladaptive to the individual who experiences it, recent evidence suggests that guilt can serve a positive societal function. Guilt proneness measured among children positively predicts future community service and college application rates, and is inversely related to criminal behavior (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Guilt proneness is associated with increased empathic responses to the suffering of others (Tangney, 1991) and increased perspective taking (Leith & Baumeister, 1998). Guilty feelings also are associated with a desire to improve subsequent performance, to apologize, and to correct a misdeed (Roseman, Wiest, & Swartz, 1994).

The beneficial features of guilt proneness are not universal outcomes of negative self-conscious emotions. In contrast to the consistently positive outcomes associated with guilt proneness, regret proneness is associated with dispositional envy and low levels of self-esteem (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). Dispositional shame proneness predicts maladaptive outcomes such as compromised immunological response (Dickerson, Kemeny, Aziz, Kim, & Fahey, 2004), school suspension, drug use, and suicide (Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

Guilt Is a Targeted Emotion

Seminal work about guilt and interpersonal behavior presented guilt as an emotion that triggers broad reparative behaviors. Carlsmith and Gross (1969), for example, found that participants who believed they had subjected a confederate to electrical shock were more likely to comply with a subsequent request, even if the requester was not the confederate. Similarly, participants who accidentally pushed someone were more likely to subsequently help an experimenter pick up papers off the ground, whether or not the experimenter was the person whom the guilty person had pushed (Konecni, 1972). In these early tests, guilt was assumed to be driving these behaviors but was never measured, leaving open the question of whether guilt did cause the behaviors.

Since those seminal experiments, research focusing on the measurement of emotion that examined guilt’s unique features has found that guilt arises from specific interpersonal transgressions, and causes specific rather than general negative feelings about the guilt-inducing act (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). When considering past transgressions, guilty people tend to focus on the transgressive act itself, wishing “if only they hadn’t” committed it, rather than wishing “if only they weren’t” deficient as a person (Niedenthal, Tangney, & Gavanski, 1994). Guilty people tend to agree with statements such as “I feel tension about something I have done” and “I cannot stop thinking about something bad I have done,” but disagree with statements such as ‘I feel like I am a bad person” (Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

The Present Research

Prior research has convincingly demonstrated the specificity of guilty feelings, but the behavioral consequences of focused guilt are largely undocumented. The present research investigates whether the targeted nature of guilt is reflected in its influence on behavior. We hypothesize that guilt prompts people to attempt to make up for their interpersonal transgressions in a targeted way. More specifically, we hypothesize that guilty people will be strategic in their attempt to remediate interpersonal transgressions by being generous only to those whom they have wronged and only when their attempts at reparations can be recognized.

Experiments 1 and 2 tested an initial hypothesis that people induced to feel guilt are (under the right circumstances) more generous than are controls. Because previous work suggests that guilty people feel bad for a specific past transgression (Niedenthal et al., 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2002), we expected the results of Experiment 3 to reveal that the way in which guilty people make up for their transgressions is specific. Guilt should not result in more generous behavior toward all potential recipients of one’s resources. Rather, guilt should lead to greater generosity only toward a person whom the guilty party has wronged.

Experiment 4 sought to address the possibility that the effects of guilt on behavior are due to “moral cleansing,” a phenomenon in which people attempt to restore self-value after committing or contemplating immoral acts (Tetlock, Kristel, Elson, Green, & Lerner, 2000). Because reparations for immoral acts focus on cleansing the individual who committed the acts, immoral behavior should prompt similar levels of reparations regardless of the recipient of the reparations. In contrast, because reparations for guilt focus on repairing the damaged relationship, guilt should prompt reparative behavior only toward a person whom the guilty person has wronged.

Finally, we tested the strategic nature of guilty behavior in Experiment 5. If guilt activates a need to repair a relationship, then guilt should encourage people to act only when their attempts at repair are likely to be successful. In other words, guilty people should only be more generous to others when the transgressed persons can notice the gesture.

In short, we propose that the targeted nature of guilty feelings has consequences for how guilt influences interpersonal behavior. Just as guilt arises from negative feelings about specific acts, we hypothesize that guilt’s effects on subsequent behavior are similarly targeted toward repairing the damage induced by those specific acts. Moreover, we hypothesize that the effects of guilt on subsequent behavior are strategic and only come into play when the guilty actor believes they have a chance to be noticed. We test our targeted nature of guilt hypothesis in five experiments.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 served as an initial test of our first hypothesis: that guilty people behave more generously. Furthermore, Experiment 1 was designed to validate our guilt induction, also used in Experiments 3, 4, and 5. In the induction, participants read either a guilt-inducing scenario or a control scenario about their behavior as a member of a project group. Participants then made decisions affecting the other group members. We predicted that participants in the guilt condition would purchase more expensive goods and contribute more to a group dinner than would comparable controls.

Method

Participants

One hundred and twenty-three residents of the United States (72 females; MAge = 37, SD = 11.9) completed the experiment online in exchange for a small payment.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to read either a control scenario or a guilt scenario. Both scenarios involved a situation in which the participant completed a group project. In the control condition, the participant showed up on time to his or her project presentation and the presentation went reasonably well. In the guilt condition, the participant stayed up late watching a movie the night before the presentation, accidentally overslept the next morning, and missed the project presentation. The other group members had to cover for her or his absence (Appendix A).

After reading their randomly assigned scenario, participants made two decisions. First, participants were informed that the restaurant they were going to after the presentation with their group was BYOB (i.e., “Bring Your Own Bottle”) and that they were to bring a bottle of wine to dinner. Participants identified which bottle of wine they would bring from a selection of eight bottles that varied by vintage, type, price, and wine spectator rating (a measure of quality; Appendix B). The eight bottles ranged in price from US$8.24 to US$19.99; wine spectator ratings correlated almost perfectly with prices (r = .98).

Next, participants were informed that, although everyone contributed what they thought they owed for the meal at the end of dinner, the amount of cash on the table for the bill at the end of the meal was US$9 short. They were asked, considering that they already contributed an amount that they believed covered their own expenses, how much extra money they would contribute toward the total bill for the group’s meal. Participants chose an amount to contribute between US$0 and US$9 in US$1 increments (Appendix B).

After answering the questions, participants were asked to think about the presentation scenario and report the extent to which they would feel 14 different emotions under those circumstances. Emotions were presented and rated in a random order on 7-point scales with endpoints “I would not experience that emotion at all” (1) and “I would experience that emotion more strongly than ever before” (7). Participants also responded to items from the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS; Marschall, Sanftner, & Tangney, 1994).

Results

Manipulation check

We created a composite score for each emotion of interest by averaging the two emotion words in the list designed to measure that emotional construct. We calculated a composite score for guilt by averaging responses to “guilty” and “sorry” (r = .89), for anger by averaging responses to “angry” and “mad” (r = .84), for disgust by averaging responses to “disgusted” and “nauseated” (r = .67), for fear by averaging responses to “afraid” and “fearful” (r = .91), for sadness by averaging responses to “sad” and “blue” (r = .77), for shame by averaging responses to “ashamed” and “shameful” (r = .94), for embarrassment by averaging responses to “embarrassed” and “humiliated” (r = .86), and for neutral by averaging responses to “unemotional” and “neutral” (r = .59).

As expected, participants who read the guilt-inducing vignette reported that they would experience more intense feelings of guilt than did participants in the control condition (MGuiltCondition = 5.63, MControlCondition = 1.48), t(121) = 15.33, p < .0005.1 Pairwise t tests revealed that participants in the guilt condition also reported more intense feelings of guilt (MGuilt = 5.63) than any other negative emotion, including anger (MAnger = 4.09), p < .0005; disgust (MDisgust = 3.78), p < .0005; fear (MFear = 3.20), p < .0005; sadness (MSadness = 4.16), p < .0005; embarrassment (MEmbarrassment = 5.35), p < .05; and shame (MShame = 5.08), p < .0005. The emotion induction was effective in terms of both magnitude and specificity.

In addition, participants’ responses to the SSGS (Marschall et al., 1994) show that participants in the guilt condition reported they would feel more guilt than did participants in the control condition (MGuiltCondition = 3.93, MControlCondition = 1.33), t(121) = 15.34, p < .0005. Participants within the guilt condition also reported significantly greater guilt scores than shame scores (MGuilt = 3.93, MShame = 3.37), t(59) = 7.83, p < .0005.

Financial decisions

For both financial decisions, participants in the guilt condition spent more than did controls. Participants in the guilt condition purchased a more expensive wine than did controls (MGuilt = US$16.60, SD = US$3.56; MControl = US$15.10, SD = 3.61), t(121) = 2.31, p < .05. Participants in the guilt-induction condition also contributed more money toward the total group bill than did controls (MGuilt = US$7.50, SD = US$2.38; MControl = US$4.89, SD = US$2.72), t(120) = 5.64, p < .0005.

Mediation analyses

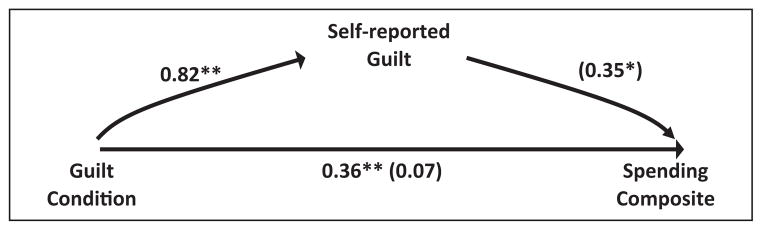

Self-reported responses about guilt significantly mediated the increase in spending (to create a “spending composite,” we averaged the two spending dependent variables), Sobel test Z = 2.42, p < .02 (Figure 1 presents parameter estimates). Importantly, no other negative emotions including shame or embarrassment significantly mediated this pattern. Similarly, participants’ self-reported responses on the guilt items of the SSGS significantly mediated the influence of guilt condition on spending (Sobel test Z = 2.12, p < .05), whereas responses to the shame items did not.

Figure 1.

Mediation by self-reported guilt.

Note: Coefficients without parentheses are parameter estimates from a simple linear regression model; coefficients in parentheses are parameter estimates from a regression model containing both predictors. Asterisks indicate parameter estimates significantly different from zero,* < .05 and ** < .01.

Discussion

Consistent with the idea that guilty people wish to make amends for their transgressions, participants reported that they would spend significantly more money on two group purchases (i.e., a bottle of wine and a meal) when they had previously transgressed against their group members (guilt condition) than when they had previously fulfilled their obligation to their group members (control condition). We observed a significant pattern of mediation of these results by self-reported feelings of guilt, but not by shame.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 examined whether the effect of guilt on giving resources to others would influence real decisions the same way that it influenced hypothetical decisions. Because previous research has found that guilt elicits similar responses in real and hypothetical scenarios (e.g., de Hooge, Nelissen, Breugelmans, & Zeelenberg, 2011), we expected guilt to increase interpersonal spending in Experiment 2, just as it did in Experiment 1.

The procedure for Experiment 2 required participants to make an interpersonal sharing decision (main dependent measure) immediately after the emotion induction. To obtain accurate measures of emotional responses, we first conducted a pretest with a separate sample of participants that measured self-reported guilt and other emotions immediately after participants completed the emotion inductions.

Pretest

Participants

Ninety-eight pretest participants (68 females; MAge = 24.0, SD = 6.2) were recruited off the street in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and were offered US$5 for participating in a 30-min laboratory experiment.

Procedure

Guilt is primarily triggered by unintentional transgressions (McGraw, 1987) and therefore we designed the guilt manipulation so that the transgression would be accidental. All pretest participants viewed a screen titled “Background information” that, in a very small font (≈ 9 pts.), described the study’s procedures in an overly detailed fashion. Participants viewed this background information screen for any length of time that they chose. We assumed, and verified, that the majority of participants would not read the background information carefully; participants spent less than a minute on average (M = 55 s, SD = 36 s) looking at the background information of more than 400 densely phrased words.

After reading the instructions, pretest participants chose whether to eat either 5 “red apple” flavored jellybeans or 5 “vomit” flavored jellybeans (80% of pretest participants chose to eat the red apple-flavored jellybeans). After choosing a flavor, pretest participants in the guilt condition were then reminded that, as was explained in the “background information,” an anonymous partner who had been paired with them would eat the flavor they decided NOT to eat. This meant that everyone in the guilt condition who chose to eat red apple-flavored jellybeans caused a partner to be assigned to eat vomit-flavored jellybeans. Pretest participants in the control condition were informed that, as was explained in the “background information,” an anonymous partner who had been paired with them would also eat the food they decided to eat.

All pretest participants then ate the five jellybeans that they selected out of an opaque cup. (The proportion of participants who selected vomit-flavored jellybeans did not differ between conditions and those participants were excluded from subsequent analyses because there was no opportunity for them to feel guilty.)

Finally, all pretest participants responded to the same battery of emotion experience questions that were completed by pretest participants in Experiment 1. As in that pretest, averaging the two emotion words designed to measure a single emotion construct created composite scores for each emotion of interest. As predicted, participants in the guilt condition reported feeling significantly more guilt than did controls (MGuiltCondition = 2.01, MControlCondition = 1.41), t(74) = 2.89, p < .01. Paired sample t tests revealed that participants in the guilt condition also reported feeling significantly more guilt (MGuilt = 2.01) than any other negative emotion, including anger (MAnger = 1.3, p < .0005), disgust (MDisgust = 1.5, p < .01), fear (MFear = 1.4, p = .001), sadness (MSadness = 1.6, p = .01), and shame (MShame = 1.7, p < .01). In short, the results of the pretest show that the guilt induction effectively and selectively induced feelings of guilt.

Main Experiment

Participants

A new sample of 24 pedestrians (10 females; MAge = 23, SD = 3.9) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, received US$5 plus the chance to earn additional money in the experiment for their participation.

Procedure

After reading the same instructions as in the pre-test, choosing a flavor of jellybean to eat, and being exposed to the behavioral guilt induction or control induction used in the pretest, all participants in the main experiment played a dictator game (Forsythe, Horowitz, Savin, & Sefton, 1994; Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1986). After learning of the jellybeans that they had selected for their anonymous partner, participants played a dictator game in which they were the dictator. Specifically, participants were given an additional US$5 in a “behavioral economics game” and were told that they could divide it however they pleased with their partner in increments of US$1 (i.e., US$5/ US$0, US$4/US$1, US$3/US$2, US$2/US$3, US$1/4, US$0/US$5). Note that in a dictator game, the dictator has total control of the division of all funds. Their partner cannot choose to reject the division chosen by the dictator.

Results

Two participants chose to eat the vomit-flavored jellybeans (one participant in each condition) and were not included in subsequent analyses.

Consistent with our predictions and the results of Experiment 1, participants in the guilt condition gave significantly more money to their partners than did controls (MGuilt = US$1.18, SD = US$0.98; MControl = US$0.36, SD = US$0.67), t(20) = 2.28, p < .04.

Discussion

Participants expended more resources on others when they committed a guilt-inducing behavior. Just as participants in Experiment 1 reported that they would contribute more to a group meal if they slept through rather than attended their group’s presentation, participants in Experiment 2 gave more in a dictator game when their decision caused another person to eat a disgusting jellybean rather than a pleasant jellybean. In both experiments, interpersonal guilt prompted people to be more generous to those whom they wronged, whether the expenditure of their resources was hypothetical or real.

Our subsequent experiments examined several explanations of this influence of guilt on the expenditure of personal resources. Consistent with evidence that guilt stems from specific events (Tangney & Dearing, 2002), we suggest that guilt plays an integral role in interpersonal expenditures of resources, influencing only those decisions that are directly related to the source of the guilt. Consequently, guilty people should expend more resources on others specifically to make amends for the guilt-inducing act (e.g., “I have erred, and so I need to exhibit generosity to those I have offended to make up for my transgression”).

It is possible, however, that guilty people may spend more because they want to repair private feelings of guilt (e.g., “I have erred, and so I need to exhibit generosity to others to show myself that I am a good person”)—an option consistent with previous scholarly explanations (Carlsmith & Gross, 1969) and with popular characterizations of guilt as a toxic emotion that makes people feel unworthy. Yet another possibility is that guilty people spend more on others to attempt to improve their general reputation by proving to others that they are a kind person, even when those others are not related to the source of their guilt (e.g., “I have erred, and so I need to exhibit generosity to others to enhance my reputation”). Experiment 3 tested these alternative possibilities.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 examined whether guilty people are more generous toward others to repair social relationships that have been damaged by transgressive acts, to ameliorate their private feelings of wrongdoing, or to repair their public reputation. Participants in guilt and control conditions made a series of allocation decisions affecting a group that they wronged (a group “integral” to their guilty feelings) or alternatively toward a new unrelated group (a group “incidental” to the guilty feelings; Schwarz & Clore, 1986). If guilty feelings trigger a need to ameliorate private feelings of guilt or to improve one’s public reputation, guilty participants should purchase more than controls both when the guilt is integral (related) and when the guilt is incidental (unrelated). In contrast, if guilty feelings trigger a need to specifically fix the transgression that caused the guilt, as we suggest, participants in the guilt condition should exhibit increased spending only when their guilt is integral but not when their guilt is incidental.

Method

Participants

One hundred and thirty-nine students at Carn-egie Mellon University (65 females; MAge = 20 years, SD = 1.1) completed the study in exchange for course credit.

Procedure

Participants read a guilt vignette or a control vignette identical to the corresponding vignette from Experiment 1, except that the Experiment 3 vignettes described the protagonist as working on a course project rather than on a company project. Half of participants (as in Experiment 1) were informed that they were going to have dinner with either their three project group members (integral group). The other participants were informed that the dinner would be with three people from a study group for a different class (incidental group; Appendix C). All participants then decided which bottle of wine to bring to dinner and how much additional money they would contribute to the dinner bill, exactly as in Experiment 1.

Because of the importance of relationship closeness in inducing guilt (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1995), and because of the potential for participants to assume they would be differentially close to their project group compared with the other study group, participants also reported how close they would feel to their dinner group on a 5-point scale with endpoints not at all (1) and extremely (5).

Results

We observed no difference in reported relationship closeness between the integral and incidental groups, F < 1, so it is not discussed further.

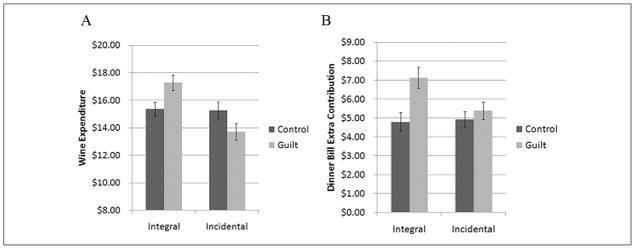

Participants’ choice of wine was submitted to a 2 (Emotion: guilt, control) × 2 (Group: incidental, integral) between-subjects ANOVA, which revealed no main effect of Emotion, F(1, 138) = 0.11, p = .74, and a significant effect of Group, such that people spent more on their project group members than on others, F(1, 138) = 10.18, p < .01. More important, the analysis revealed the predicted Emotion × Group interaction, F(1, 138) = 9.01, p < .01. Guilty participants spent more than did controls when the group they were purchasing for was integral to their guilty feelings (MGuilt/ Integral = US$17.29, SD = US$3.17; MControl/Integral = US$15.36, SD = US$3.20), t(71) = 2.57, p = .01, but guilty participants did not spend more than controls when the group was incidental to their guilty feelings, that is, when the recipients were not related to the source of the guilt (MGuilt/Incidental = US$13.71, SD = US$3.80; MControl/Incidental = US$15.26, SD = US$3.19), t(64) = 1.74, p = .09. If anything, participants in the guilt condition actually spent slightly less than did controls when they were buying for people who were not in their project group, p = .09 (Figure 2, left panel).

Figure 2.

Guilt increases spending only when guilt is relevant to the recipient.

Note: Guilty people spend more on others than do controls when choosing wine to share (Panel A) and contributing extra money to a dinner bill (Panel B), but only when the recipients are “integral,” or related, to source of their emotion.

Participants’ dinner contributions exhibited a similar pattern. A 2 (Emotion: guilt, control) × 2 (Group: integral, incidental) between-subjects ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Emotion such that participants in the guilt condition contributed more to the bill than did controls, F(1, 138) = 10.65, p < .01. We also observed a marginally significant effect of Group such that participants in the integral condition contributed more to the bill than did participants in the incidental condition, F(1, 138) = 3.43, p = .07. More important, we observed the predicted Emotion × Group interaction, F(1, 138) = 4.75, p < .05 (Figure 2, right panel). Guilty participants contributed more to the bill than did controls when the dinner party was integral to their guilty feelings (MGuilt/Integral = US$7.13, SD = US$2.61; MControl/Integral = US$4.79, SD = US$2.37), t(71) = 3.97, p < .001, but guilty participants did not contribute more to the bill than did controls when the dinner party was incidental to their guilty feelings (MGuilt/Incidental = US$5.39, SD = US$2.54; MControl/ Incidental = US$4.93, SD = US$2.46), t < 1.

Discussion

Rather than ameliorate one’s self-perception or general reputation, guilt appears to increase generosity toward others only when it might remediate specific interpersonal transgressions. Participants led to feel guilt in Experiment 3 only spent more of their resources on a dinner party—buying a bottle of wine and contributing to the tip—when the members of the party were people whom they had wronged. Consistent with previous work that characterizes guilt as an emotion that arises from specific actions (Tangney & Dearing, 2002), the reparative action motivated by guilt has similarly specific targets.

Experiment 4

In Experiment 4, we directly compared the consequences of guilt with the consequences of immoral feelings. Guilt is often considered to be fundamentally a moral emotion or, at the least, to be the result of a moral violation (e.g., Ausubel, 1955; Gehm & Scherer, 1988). Although guilt and immoral feelings can co-occur (Tangney, 1992), guilt also can result from essentially amoral violations, such as when someone accidentally harms someone else or unintentionally fails to fulfill an interpersonal obligation (Baumeister et al., 1995; McGraw, 1987). Although feelings of immorality and guilt share similarities—both are unpleasant and both prompt restorative action—the two types of feelings can cause markedly different responses when operating independently. Immoral acts or even immoral thoughts tend to prompt general cleansing responses (Tetlock et al., 2000) or self-punishment (Wallington, 1973). Guilt, by contrast, appears to cause reparative efforts specifically designed to mend interpersonal wrongs.

Experiment 4 attempted to compare guilt responses to responses based on immoral feelings. In the experiment, participants first read a guilt or immorality induction. Then, participants decided either about making a contribution to their project group or about making a contribution to a charity. Because the nature of immoral feelings and guilt is different, we predicted that the consequences of the two feelings would be different as well. Specifically, we hypothesized that people experiencing feelings of immorality should contribute similar amounts to others regardless of the recipient type (project group or charity); however, guilty people should contribute more when giving to people whom they have wronged as compared with a deserving but different group such as a charity.

Method

Participants

One hundred and four residents of the United States (70 females; MAge = 38, SD = 13.3) completed the study on the Internet in exchange for a small payment.

Procedure

Participants read either the guilt scenario from Experiment 1, or they read a new immorality scenario. In the immorality scenario, participants read that they had been up late the night before their group presentation preparing materials for a class presentation. They could not find information that they needed for the presentation, and so they stole slides from a group’s presentation from the previous year. In the scenario, it was clear that no one would ever know that participants had plagiarized (Appendix D).

After reading the scenario, participants made one of the two decisions. Half of the participants decided how much extra money they would contribute to the group dinner bill; answer choices ranged from US$0 to US$10. The other half of participants decided whether they would donate to a local food bank by adding a donation to their dinner bill; answer choices ranged from US$0 to US$10. After making the financial decision, participants responded to a modified SSGS.

Results

Manipulation check

Because we used a new scenario, we again measured emotional responses to ensure the emotion inductions were effective. We used a modified SSGS (Marschall et al., 1994) that included three new items for immorality: “I would feel immoral,” “I would feel unethical,” and “I would feel like I was morally corrupt” (α = .89).

Participants in the guilt condition reported greater guilt than did participants in the immoral condition (MGuiltCondition = 4.42, MImmoralCondition = 3.75), t(102) = 4.10, p < .0005, and participants in the immoral condition reported greater feelings of immorality than did participants in the guilt condition (MImmoralCondition = 3.45, MGuiltCondition = 2.69), t(102) = 3.19, p < .01.

Main results

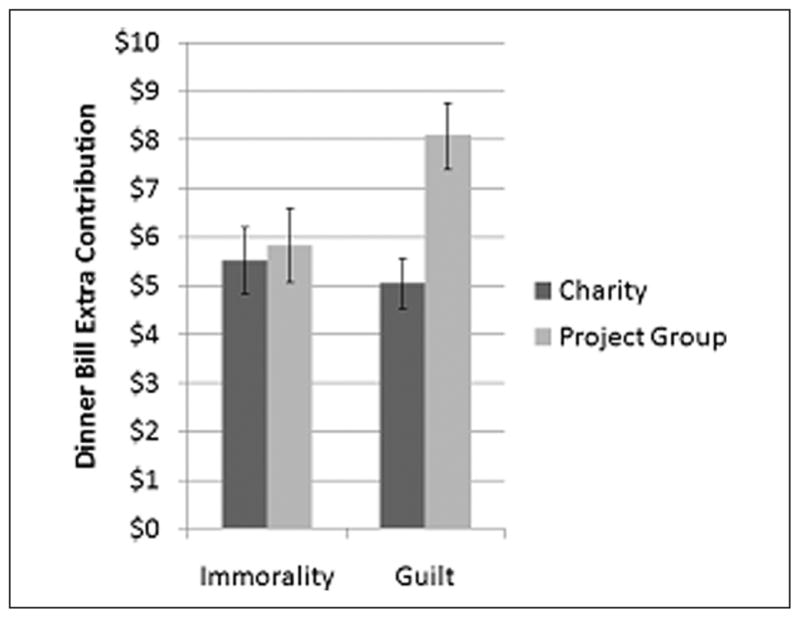

Participants’ spending decision was submitted to a 2 (Emotion type: guilty feelings, immoral feelings) × 2 (Decision type: group contribution, charity contribution) ANOVA, which revealed no significant main effect of Emotion type, F < 1, and a significant main effect of Decision type such that participants in the group-contribution condition spent more than did participants in the charity-contribution condition, F(1, 100) = 6.73, p < .05. More important, the analysis revealed the predicted Emotion × Decision type interaction, F(1, 100) = 4.46, p < .05. As illustrated by Figure 3, guilty participants spent significantly more money when they spent on their project group members than on charity (MGroup = US$8.09, SD = US$3.00; MCharity = US$5.05, SD = US$3.43), t(41) = 3.10, p < .01; however, participants in the immoral condition spent similar amounts regardless of recipient type (MGroup = US$5.84, SD = US$2.94; MCharity = US$5.53, SD = US$3.61), t < 1.

Figure 3.

Guilt, but not immorality, prompts different spending based on recipient.

Note: People experiencing feelings of immorality spend similarly regardless of recipient type. People experiencing feelings of guilt spend selectively, increasing spending only when the recipient was a victim of their transgression (in this case, in their project group).

Discussion

Although feelings of guilt and feelings of immorality can co-occur, they are distinct constructs and can have unique influences on behavior. Whereas committing an immoral act leads to similar levels of generosity regardless of recipient type, guilty transgressions lead to targeted generosity toward the individuals whom the guilty party injured. In other words, guilty people spend more on those whom they have wronged, but they do not increase spending for unrelated, but morally praiseworthy causes, such as donating to charity. It appears that when guilt is not coupled with immorality, guilty individuals do not morally cleanse themselves by engaging in general resource expenditure. Rather, guilt prompts targeted attempts at relationship repair.

Experiment 5

In Experiment 5, we further examined the specificity of guilt’s influence on interpersonal spending. Whereas the previous two experiments suggest that the influence of guilt on interpersonal spending is targeted—that it only influences the expenditure of resources on the party wronged—Experiment 5 examined whether the influence of guilt on interpersonal spending is also strategic. In other words, do guilty people take any opportunity to make amends with those whom they have wronged, or do guilty people expend effort to make amends only when one is fairly confident that those efforts will be noticed?

We investigated these two possibilities by modifying the wine-buying scenario used in Experiments 1 and 3. In an “expert” condition, participants’ project group members were wine experts who would know how much the participant spent on the bottle of wine that they purchased. In a “novice” condition, participants’ project group members had no knowledge of wine and were unlikely to be able to know how much the participant spent. If guilty feelings trigger blanket attempts to remediate damaged social relationships, there should be no difference in amounts spent on wine in the expert and novice conditions. However, if guilty people are strategic in their attempts to repair the relationship, guilty participants should spend more only when recipients can notice the increased effort by the guilty person—in the expert condition.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and seventy residents of the United States (155 females; MAge = 33, SD = 11.9) completed the study online in exchange for a small payment.

Procedure

Participants read either the guilt or the control scenario used in Experiment 1. They were then informed that they were going to have dinner with the members of their project group. Next, they were presented with the wine-purchase scenario and informed either that their fellow group members were wine experts (expert condition) or that their fellow group members had no knowledge of wine (novice condition; Appendix E). Participants then chose which bottle of wine they would purchase for the dinner.

Results

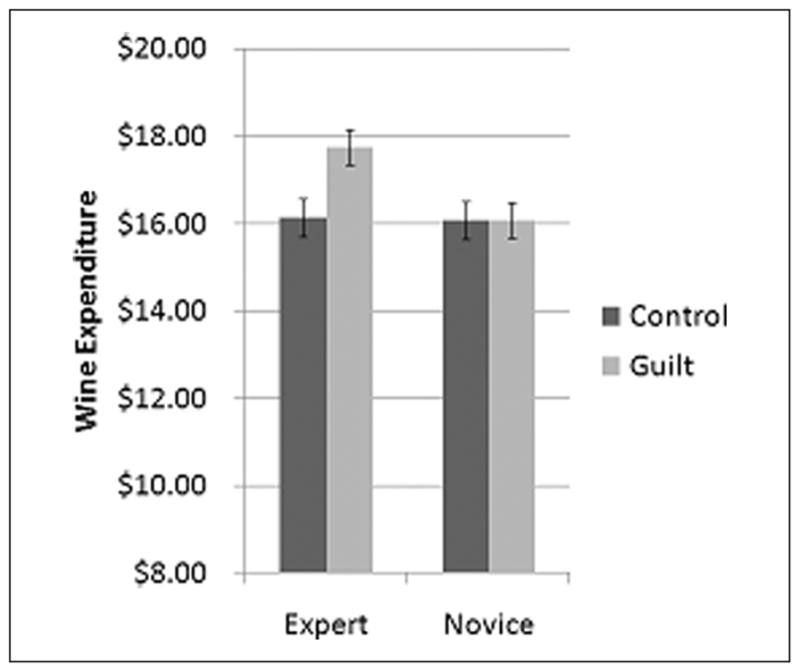

Participants’ wine decision was submitted to a 2 (Emotion: guilt, control) × 2 (Group knowledge: experts, novice) ANOVA, which revealed a significant main effect of Emotion such that participants in the guilt condition spent more than did participants in the control condition, F(1, 266) = 4.04, p < .05, and a significant main effect of recipient expertise such that participants in the expert condition spent more than did participants in the novice condition, F(1, 266) = 4.68, p < .05. More important, the analysis revealed the predicted Emotion × Expertise interaction, F(1, 266) = 3.92, p < .05. As illustrated by Figure 4, guilty participants spent more than did controls when their project group members were wine experts (MGuilt = US$17.75, SD = US$2.98; MControl = US$16.14, SD = US$3.15), t(120) = 2.86, p < .01, but guilty participants did not spend more than did controls when their project group members were wine novices (MGuilt = US$16.08, SD = US$3.61; MControl = US$16.07, SD = US$3.27), t(146) = .02, p = .98.

Figure 4.

Guilt increases spending only when recipients can notice the gesture.

Note: Guilty people spend more on wine to share with others than do controls, but only when the recipients are wine experts and are able to notice the gesture.

Discussion

The influence of guilt on interpersonal spending appears not only targeted but also strategic. Guilty parties expended more of their resources than did controls when the party they wronged could notice the magnitude of their expenditure, but they did not spend more when the party wronged could not notice the amount of resources they expended. Guilt does not appear to induce general attempts to make oneself feel better about one’s relationship with a wronged party. Instead, it appears to operate in a conscious and strategic way to prompt resource expenditure for relationship repair.

General Discussion

The present research elucidates the influence of guilt on generous behavior. Guilt does not lead to increased generosity toward all. Instead, it increases generosity toward those whom one has wronged and only when those whom one has wronged can notice the gesture. The influence of guilt does not seem to prompt general moral “cleansing” in response to transgressions. Rather, the picture that emerges about guilt and interpersonal decisions is one in which guilt specifically and strategically prompts people to repair specific social transgressions.

The findings provide important supporting evidence to the perspective that guilty feelings are targeted in nature. Whereas previous research focuses on how guilty feelings arise from specific transgressive acts (Niedenthal et al., 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2002), the present research investigates how these focused feelings influence subsequent behavior. We found that, just as guilt tends to arise from specific transgressions, the actions triggered by guilt tend to focus on specific measures to ameliorate those transgressions as well.

The findings also contribute evidence to the perspective that guilt has beneficial interpersonal functions (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). We suggest that the precision with which guilt prompts relationship repair could be one reason why guilt is associated with so many positive outcomes (Leith & Baumeister, 1998; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Guilt moves people to act to repair a wrong, it moves them to act exactly and only where the offense has occurred, and it moves them to act only when the gesture to make amends can be recognized. Subsequently, such amends may allow both parties to move on securely in their relationship. Interestingly, most of the scenarios in our studies focused on relationships between acquaintances rather than between close friends or family. Because guilt is associated most strongly with close or communal relationships (Baumeister et al., 1995), we might expect the observed effects to be even stronger in the context of close relationships.

Although the present research advances our understanding of guilt’s influence on interpersonal decision making, it cannot speak to the true efficacy of the repair attempts. In other words, we cannot tell whether guilty participants’ attempts to repair relationships by increasing generosity toward others are always effective in repairing those relationships. Furthermore, we do not know the types of amends that are most successful. Although repairs such as offering apologies or favors may be as helpful in repairing relationships as explicit resource expenditure, it could be that spending is the best way to make amends because a measurable sacrifice has been made by the transgressor, and the benefit to the recipient is tangible. There also is new evidence that guilt-induced attempts to make amends with one person may come at the expense of one’s relationship with another person (de Hooge et al., 2011), making it at least possible for guilt to help fix one relationship while taking focus away from another relationship and potentially causing new damage. Future work is needed to determine whether the net effects of interpersonal guilt are truly beneficial for maintaining all of one’s important social bonds.

In conclusion, the present research elucidates the role of guilt as a social emotion that influences interpersonal decision making. Guilt prompts individuals to expend their resources to make amends when they have jeopardized a relationship’s health. Guilt prompts focused reparative behavior toward the persons whom the guilty person has injured, and only does so when the wronged parties are likely to recognize the gesture. In sum, guilt evokes targeted and strategic generosity to maintain social relationships.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: A grant from the Center for Behavioral Decision Research at Carnegie Mellon University supported this research.

Appendix A

Control Condition

Imagine that you are part of a team presentation that could bring in a large amount of new business to your company. Your team has been working extremely hard on the presentation and you believe you will represent your company well. The night before your presentation you do some last minute preparations, set your alarm for the morning, and go to bed. The next day you arrive on time and the presentation with your group members goes reasonably well.

Guilt Condition

Imagine that you are part of a team presentation that could bring in a large amount of new business to your company. Your team has been working extremely hard on the presentation and you believe you will represent your company well. However, the night before your presentation you stay up late watching a movie. You are so exhausted by the time it is over that you forget to set your alarm before bed. The next morning, you wake up and realize that you slept through your presentation. As a result, the other members of your group scrambled at the last minute and covered for your absence.

Appendix B

-

Q1. In the evening after your presentation, your group decides to go out for dinner at a local Italian restaurant and you have decided to bring a red Italian wine to go along with the meal. Although you may not be an expert, you look at the Wine Spectator scores of each wine in a display. Which of the following bottles of wine would you purchase?

Vintage Type Price Wine Spectator Rating 2004 Umani Ronchi Montepulciano d’Abruzzo Montepulciano, Sangiovese US$8.24 (unrated) 2002 Danzante Sangiovese US$9.29 (unrated) 2005 Danzante Chianti, Sangiovese US$10.29 84 2005 Falesco Vitiano Rosso Sangiovese US$11.84 85 2003 Zenato Valpolicella Sangiovese Classico Superiore US$13.50 87 2000 Salcheto Vino Nobile di Montepulciano Montepulciano Sangiovese US$15.25 88 2003 Di Majo Norante Ramitello Rosso Sangiovese US$16.79 90 2005 Marchesi di Barolo Barbera d’Alba Ruvei Rosso Barbera US$19.99 91 -

Q2. At the end of dinner, all four of you pay what you think you owe. Someone counts the money and finds out that you are US$9.00 short. You think you have contributed what you owe, but consider covering part of this difference. How much would you contribute? (Circle the amount you would contribute.)

US$0 US$1 US$2 US$3 US$4 US$5 US$6 US$7 US$8 US$9

Appendix C

Integral Condition

Q1. In the evening after your presentation, your project group of four people total decides to go out for dinner at a local Italian restaurant and you have decided to bring a red Italian wine to go along with the meal. Although you may not be an expert, you look at the Wine Spectator scores of each wine in a display. Which of the following bottles of wine would you purchase?

Incidental Condition

Q1. In the evening after your presentation, you and three people from a study group for a different class decide to go out for dinner at a local Ital-ian restaurant and you have decided to bring a red Italian wine to go along with the meal. Although you may not be an expert, you look at the Wine Spectator scores of each wine in a display. Which of the following bottles of wine would you purchase?

Appendix D

Immoral Condition

Imagine that you are preparing for a group presentation that is a large part of your final grade for a class. Your group has been working extremely hard on the presentation and you believe you will perform well. However, the night before your presentation you are up very late putting together your final materials. At the end of the night, you cannot find the information that you need for part of the presentation, so you steal several slides from another group’s presentation from the previous year. The instructor is new this year and will never know that you plagiarized someone else’s work. The next day, you arrive on time and the presentation with your group members goes reasonably well.

Appendix E

Novice Condition

In the evening after your presentation, your group decides to go out for dinner at a local Italian restaurant. You have decided to bring a red Italian wine to go along with the meal.

Although you are not a wine expert, and your fellow group members have no wine knowledge, you look at the Wine Spectator scores of each wine in a display. Which of the following bottles of wine would you purchase to share with your group?

Expert Condition

In the evening after your presentation, your group decides to go out for dinner at a local Italian restaurant. You’ve decided to bring a red Italian wine to go along with the meal.

Although you are not a wine expert, your fellow group members are wine experts. You look at the Wine Spectator scores of each wine in a display. Which of the following bottles of wine would you purchase to share with your group?

Footnotes

Participants with the fastest 5% completion times and participants whose IP address appeared multiple times (suggesting multiple study attempts by one person; 12 participants, 1.8% of total) were excluded. No meaningful difference in conclusions resulted; however, as expected, statistical significance improved. One case is notable: the Study 5 interaction result is marginally significant with all participants included and fully significant when those indicated above are excluded.

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amodio DM, Devine PG, Harmon-Jones E. A dynamic model of guilt: Implications for motivation and self-regulation in the context of prejudice. Psychological Science. 2007;18:524–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel DP. Relationships between shame and guilt in the socialization process. Psychological Review. 1955;67:378–390. doi: 10.1037/h0042534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Stillwell AM, Heatherton TF. Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:243–267. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Stillwell AM, Heatherton TF. Personal narratives about guilt: Role in action control and interpersonal relationships. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1995;17:173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsmith JM, Gross AE. Some effects of guilt on compliance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1969;11:232–239. doi: 10.1037/h0027039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell S. Escaping toxic guilt: Five proven steps to free yourself from guilt for good. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- de Hooge IE, Nelissen RMA, Breugelmans SM, Zeelenberg M. What is moral about guilt? Acting “pro-socially” at the disadvantage of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:462–473. doi: 10.1037/a0021459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hooge IE, Zeelenberg M, Breugelmans SM. Moral sentiments and cooperation: Differential influences of shame and guilt. Cognition & Emotion. 2007;21:1025–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Kim KH, Fahey JL. Immunological effects of induced shame and guilt. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:124–131. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097338.75454.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P. An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion. 1992;6:169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe R, Horowitz JL, Savin NE, Sefton M. Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior. 1994;6:347–369. [Google Scholar]

- Forward S, Frazier D. Emotional blackmail: When the people in your life use fear, obligation, and guilt to manipulate you. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gehm TL, Scherer KR. Relating situation evaluation to emotion differentiation: Nonmetric analysis of cross-cultural questionnaire data. In: Scherer KR, editor. Facets of emotion: Recent research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Sorolla R. Guilty pleasures and grim necessities: Affective attitudes in dilemmas of self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:206–221. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jampolsky GG. Good-Bye to guilt: Releasing fear through forgiveness. New York, NY: Bantam; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business. 1986;59:S285–S300. [Google Scholar]

- Konecni VJ. Some effects of guilt on compliance: A field replication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;23:30–32. doi: 10.1037/h0032875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leith KP, Baumeister RF. Empathy, shame, guilt, and narratives of interpersonal conflicts: Guilt prone people are better at perspective taking. Journal of Personality. 1998;66:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of emotion. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993. pp. 623–636. [Google Scholar]

- Marschall D, Sanftner J, Tangney JP. The State Shame and Guilt Scale. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw KM. Guilt following transgression: An attribution of responsibility approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:247–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedenthal PM, Tangney JP, Gavanski I. “If only I weren’t” versus “If only I hadn’t”: Distinguishing shame and guilt in counterfactual thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:585–595. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseman IJ, Wiest C, Swartz TS. Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:206–621. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Clore GL. Feelings and phenomenal experiences. In: Kruglanski A, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York, NY: Guilford; 1986. pp. 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP. Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:598–607. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP. Situational determinants of shame and guilt in young adulthood. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP. Conceptual and methodological issues in the assessment of shame and guilt. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:741–754. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL. Shame and guilt. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock PE, Kristel OV, Elson SB, Green MC, Lerner JS. The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical coun-terfactuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:853–870. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy JL, Robins RW. Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:1339–1351. doi: 10.1177/0146167206290212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy JL, Robins RW. The self in self-conscious emotions: A cognitive appraisal approach. In: Tracy JL, Robins RW, Tangney JP, editors. The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford; 2007. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wallington SA. Consequences of transgression: Self-punishment and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;28:1–7. doi: 10.1037/h0035576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeelenberg M, Breugelmans SM. The role of interpersonal harm in distinguishing regret from guilt. Emotion. 2008;8:589–596. doi: 10.1037/a0012894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2007;17:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zemack-Rugar Y, Bettman JR, Fitzsimons GJ. The effects of nonconsciously priming emotion concepts on behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:927–939. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]