Abstract

Differentiation is defined as the ability of a cell to acquire full functional behavior. For instance, the function of bladder urothelium is to act as a barrier to the diffusion of solutes into or out of the urine after excretion by the kidney. The urothelium also serves to protect the detrusor muscle from toxins present in stored urine. A major event in the initiation and progression of bladder cancer is loss of urothelial differentiation. This is important because less differentiated urothelial tumors (higher histologic tumor grade) are typically associated with increased biologic and clinical aggressiveness. The differentiation status of urothelial carcinomas can be assessed by histopathologic examination and is reflected in the assignment of a histologic grade (low-grade or high-grade). Although typically limited to morphologic evaluation in most routine diagnostic practices, tumor grade can also be assessed using biochemical markers. Indeed, current pathological analysis of tumor specimens is increasingly reliant on molecular phenotyping. Thus, high priorities for bladder cancer research include identification of (1) biomarkers that will enable the identification of high grade T1 tumors that pose the most threat and require the most aggressive treatment; (2) biomarkers that predict the likelihood that a low grade, American Joint Committee on Cancer stage pTa bladder tumor will progress into an invasive carcinoma with metastatic potential; (3) biomarkers that indicate which pTa tumors are most likely to recur, thus enabling clinicians to prospectively identify patients who require aggressive treatment; and (4) how these markers might contribute to biological processes that underlie tumor progression and metastasis, potentially through loss of terminal differentiation. This review will discuss the proteins associated with urothelial cell differentiation, with a focus on those implicated in bladder cancer, and other proteins that may be involved in neoplastic progression. It is hoped that ongoing discoveries associated with the study of these differentiation-promoting proteins can be translated into the clinic to positively impact patient care.

Keywords: bladder cancer, transcription factors, differentiation, FoxA, retinoic acid, PPAR gamma

Introduction

During development, cells undergo a series of genetic and epigenetic changes whereby they acquire specific characteristics that enable them to fulfill specialized functions. In response to insult or injury this differentiation process may be reversed to enable cells and tissues to undergo repair, through proliferation and other processes, before re-acquisition of their differentiated characteristics. In neoplasia, however, this process potentially fails to occur normally, leading ultimately to uncontrolled growth and tumor formation. Thus, cancer can be viewed, in part, as a defect in differentiation. In this review, we consider urothelial differentiation as a framework for evaluating molecular regulators implicated in the pathogenesis of urothelial cancer, and consider how such information could be used clinically as biomarkers of outcome, or as therapeutic targets.

Differentiation Characteristics of Normal Urothelium

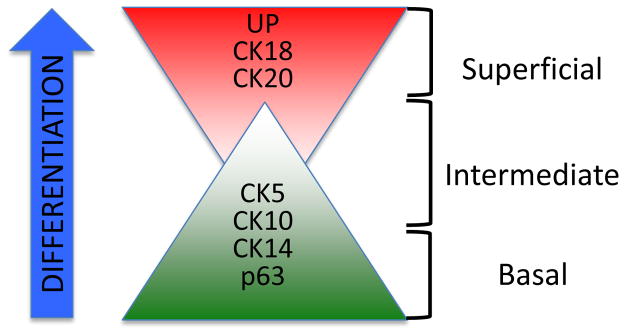

The urothelium that lines the bladder is a pseudostratified epithelium comprising discrete populations of epithelial cells that can be identified as basal, intermediate or superficial based on their localization relative to the basement membrane or bladder lumen, as well as expression of specific marker proteins (Figure 1). Although this topic has been covered in many excellent articles [1, 2], several points are germane to the discussion here. The urothelium is specified during embryonic development in response to inductive signals from the developing mesenchyme, and is characterized by a highly specialized superstructure on its luminal aspect termed the asymmetric unit membrane (AUM) [3–5]. The AUM results from the apical presentation of a family of uroplakin (UP) proteins on the most superficial ‘umbrella’ cell layer [6–8] that assemble into plaque-like structures, and serves as one component of a barrier to urine [9, 10]. UP expression is diminished in intermediate cells and largely absent in basal cells, whereas expression of other markers such as p63 and selected cytokeratins is increased, in line with the less differentiated nature of these populations. Thus, one can envision a spectrum of differentiation marker expression, with a specific complement of genes/proteins corresponding to discrete cell populations with specific fates. It is generally accepted that differentiation of cells within the urothelium follows a pattern similar to that in other epithelia such as the gut and skin, where cells in the basal compartment that are thought to harbor the progenitor population mature into progressively more differentiated intermediate cells and ultimately terminally differentiated superficial cells. However, several recent studies suggest that basal/intermediate and superficial cells derive from distinct lineages [11, 12].

Figure 1.

Normal bladder urothelium displays a spectrum of protein markers identifying subpopulations of specific cell types. Although the pathways required for urothelial differentiation are not completely understood, it is theorized that differentiation of cytokeratin (CK) 14 and CK10 basal cells results in an intermediate, CK5 positive cell population. Presence of uroplakin (UP) and cytokeratin 18/20 positive cells, as well as absence of p63 expression indicates the presence of superficial “umbrella cells” which are often lost early in bladder cancer progression.

Urothelial Differentiation as a Paradigm for Identifying Factors Implicated in Urothelial Cancer Development

As described by Hanahan and Weinberg, tumor cells display a number of characteristic ‘hallmarks’, including self-sufficient growth, unlimited replicative potential, and resistance to growth inhibitory signals among others [13]. In contrast, fully differentiated cells, such as those in the normal urothelium, display limited growth potential. Thus, if cellular differentiation is defined as the attainment of full functional capacity, cancer can be defined, in part, by loss of the differentiated phenotype. For example, in addition to promoting tumor progression and metastatic dissemination, loss of differentiation in urothelial carcinoma is accompanied by diminished barrier function. Conversely, alteration of the urothelial barrier following augmentation cystoplasty has been linked to increased susceptibility to neoplastic transformation [14–16], highlighting the intimate relationship between loss of differentiation and development of cancer.

Based on its diverse clinical presentation, as well as extensive molecular genetics analysis, it is now accepted that bladder cancer develops along a number of discrete pathways that display characteristic chromosomal alterations (reviewed in [17]). Broadly speaking, lesions can be classified into (i) well differentiated, non-invasive papillary cancers characterized by deletions in chromosome 9; (ii) poorly differentiated muscle-invasive tumors that show alterations in canonical tumor suppressors and oncogenes including p53, Rb and PTEN; and (iii) a distinct entity, carcinoma in situ (CIS) that, although confined to the urothelium, exists as a flat, non-papillary, poorly differentiated lesion displaying genetic alterations characteristic of both papillary and muscle-invasive tumors [18] Importantly, the presence of CIS correlates strongly with the risk of invasive disease, demonstrating the close association between loss of urothelial differentiation and ultimate development of aggressive bladder cancer.

The differentiation state of cells is a function of how cells respond and communicate with the local tissue milieu, and communication between stromal/mesenchymal and epithelial tissue compartments is an essential event for both the normal development of organs, as well as their maintenance [19–23], [14]. While bladder mesenchyme provides signals that program the target epithelium to maintain a urothelial phenotype, epithelium must be receptive to these signals for proper differentiation. In addition, urothelial cells also send reciprocal signals to promote terminal differentiation of the bladder mesenchyme [24]. Cells utilize a number of mechanisms to respond to their microenvironment. For example, transcription factors function to integrate incoming signals from activated cell surface receptors, enabling cells to respond to microenvironmental stimuli. Thus, cell surface receptors and transcription factors represent excellent candidate biomarkers for (1) the extent of urothelial differentiation, (2) cancer diagnosis and/or prognosis, and (3) identification of groups of deregulated genes which could serve as novel targets for personalized therapy.

Histopathology of Urothelial Neoplasia and Utility of Existing Biomarkers

By definition, increased urothelial cell growth is accompanied by a loss of differentiation. Classification of malignant lesions of urothelium is performed according to current World Health Organization and International Society of Urologic Pathologists criteria (WHO/ISUP 2004) [7, 25]. Tumors are graded histologically based on their architectural and cellular characteristics, and all malignant urothelial neoplasms display a number of common histologic features related to loss of differentiation [25–27], [25], [28], [7, 8]. However, accurate histopathologic classification of bladder cancer cases can be challenging. While much effort has been expended to identify molecular features of tumors for use in parallel with histologic information to better stratify patients, most molecular abnormalities identified to date are limited to high-grade lesions. For example, only high-grade, poorly-differentiated urothelial lesions display aneuploidy and genetic instability [8, 29–31], abnormal localization of cytokeratin 20 (CK20) and CD44, and loss of p63 expression and nuclear accumulation of p53 [25, 29, 32–35]. Thus, the identification of molecular events that define early alterations in the differentiated phenotype of urothelium should have the greatest prognostic utility.

Cell Surface Receptor Pathways Implicated in Urothelial Differentiation and Development of Urothelial Carcinoma

EGFR Axis in Urothelium

The EGFR axis comprises the EGFR and three related receptors of the v-erb-b erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene (ERBB), ERBB2, ERBB3 and ERBB4, along with a family of 15 peptide ligands that display common structural features. All four receptors, and multiple ligands are expressed in normal urothelium and bladder cancer tissue, albeit to different extents [36–38]. In addition, aberrant expression and/or activity of ERBB receptors have been linked to urothelial carcinoma development and progression [39–42]. Using a genetic approach to target overexpression specifically to the urothelium in mice, the EGFR was found to drive urothelial hyperplasia [43], but did not promote development of carcinomas. However, EGFR overexpression cooperated with SV40 large T antigen-mediated suppression of p53 and pRb function to drive the development of high-grade, but non-invasive urothelial carcinomas [43]. These observations suggest that upregulation of EGFR-dependent signaling is necessary but not sufficient for urothelial cancer development.

The EGFR ligand, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) has also been implicated in bladder cancer. Analysis of human cancer specimens using an antibody against the cytoplasmic domain of HB-EGF revealed that, although the level of HB-EGF did not change with tumor progression, there was a significant increase in nuclear localization of HB-EGF in aggressive lesions [44]. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that enhanced nuclear localization of HB-EGF was associated with reduced survival [44], [45]. In independent studies, it was shown that the HB-EGF precursor can be processed to yield a C-terminal fragment that transits to the nucleus where it binds to and inactivates the transcriptional repressors PLZF and Bcl6 either by promoting nuclear export or degradation [46–49]. As a result, cell cycle transit is restored leading to enhanced proliferation. Together, these findings suggest a receptor- independent mechanism whereby EGFR ligands can elicit tumor progression.

Consistent with its role as a transducer of signals that promote epithelial mitogenesis and growth, activation of the EGFR was shown to negatively regulate urothelial cell differentiation. In particular, pharmacologic inhibition of EGFR kinase activity or its effectors MEK/ERK or PI3-kinase enhanced PPARγ-induced expression of uroplakin mRNA [50] and tight junction formation [51] in cultured urothelial cells. Notably, EGFR inhibition in the absence of PPARγ activation did not alter uroplakin expression, indicating that suppression of EGFR-mediated signals, while required, is insufficient on its own to promote differentiation. In addition, activation of EGFR by heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) on the apical surface of umbrella cells has been shown to activate exocytosis. This regulated exocytosis results in the increase of umbrella cell surface area in response to stretch [52], explaining the ability of the urothelium to distend in response to bladder filling. Therefore, the EGFR axis activity is implicated in urothelial differentiation, physiology and cancer.

FGFs in the Urothelium

Previous studies indicate FGF-7 is essential for urothelial stratification, which is required for urothelial function in vivo. In addition, the FGF pathway is also implicated in the development of urothelial carcinoma. FGF-7 is normally expressed by stromal cells in the bladder that signal in a paracrine manner to FGF receptor-expressing urothelial cells [53]. Somatic missense mutations in the FGFR3 gene have been shown to be more prevalent in low grade, Ta stage tumors [54, 55], suggesting a possible association with early loss of differentiation. Interestingly, the urothelium of FGF-7-null mice showed a profound reduction in thickness compared to wild type tissue, that results from the absence of intermediate cell layers [56]. In addition, FGF-7 is mitogenic for urothelial cells and appears to retard the maturation of urothelial cells to a terminally differentiated phenotype [57, 58].

Shh Pathway in the Urothelium

The Shh signaling pathway is important for de novo differentiation induced via epithelial-mesenchymal communication as well as potentially in the development of bladder cancer. The Shh pathway consists of the ligand Shh, its cognate receptor patched (Ptc1) and intracellular effectors (transcription factors Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3). Different components of the Shh pathway have been implicated in normal bladder development and differentiation [59, 60]. In a study of over 1600 human urothelial carcinoma samples, 11 members of the Shh family were genotyped for 177 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [61]. This study revealed that nine Gli3 SNPs were predictive of clinical outcome in non-muscle invasive bladder carcinoma (NMIBC) patients following BCG treatment. Importantly, two of these SNPs remained significant following statistical adjustment for multiple comparisons, suggesting that genetic alterations in the Shh pathway can influence response to therapy in patients with NMIBC.

Transcription Factors Implicated in Urothelial Differentiation and Development of Urothelial Carcinoma

Retinoid Signaling

Retinoids are known to facilitate changes in gene expression through binding to retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs), which belong to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of transcription factors [62]. Typical responses are transduced through binding of homo- and hetero-dimers of RAR and RXR receptor complexes to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) present in the promoters of target genes [63]. Vitamin A/retinoid-mediated signaling pathways have been implicated in critical processes involved in the formation of the bladder from the urogenital sinus [64]; [65] as well as in key stages of urothelial specification and maturation.

In addition, vitamin A/retinoid pathways have been linked to development of urothelial malignancies. For instance, RARβ mRNA levels are altered in bladder cancer [66, 67], and mutations in highly conserved regions of the RARα gene have been detected in the immortalized urothelial cell line, HUC-BC, suggesting that retinoid signaling may be a frequent target of inactivation in bladder carcinogenesis [68]. However lack of reliable antibodies has made thorough characterization of RAR and RXR expression at the protein level in human tissue difficult. Additionally, the observation that vitamin A deficiency in rodents induces keratinizing squamous metaplasia, a suspected risk factor for the development of squamous cell carcinoma in humans [69, 70], further suggests that this pathway is important for development of urothelial tumors.

Interest in the use of retinoid analogues for the treatment of bladder cancer resulted from the observation that this class of compounds was effective in the treatment of carcinogen-induced tumors in rats [71, 72]. In vitro work suggests human bladder cancer cell lines are relatively resistant to the major biologically active derivative of vitamin A, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). However, treatment with retinoid analogues such as N-4-hydroxyphenyl-retinamide (Fenretinide or 4-HPR) and 6-[3-(1-adamantyl)-4 hydroxyphenyl]-2-napthalene carboxylic acid (CD437) resulted in apoptosis, G1 cell cycle arrest, and decreases in cell growth [73]. While in vitro work showed the potential therapeutic utility of Fenretinide/4-HPR, the compound failed to prevent disease recurrence in patients with NMIBC in a multicenter Phase III prevention [74]. However, subgroup analysis showed that high-risk patients receiving BCG and treated with 4-HPR were 1/3 as likely to develop recurrence as those administered placebo. The authors suggested BCG treatment may potentiate the action of fenretinide. Another synthetic retinoid, Etretinate (Tegison) was also evaluated in a prospective randomized double-blind multicenter trial in Switzerland [75]. Results of this study showed that while time to first recurrence was similar in placebo and Etretinate treatment groups, time to second recurrence was significantly longer in the Etretinate group. This resulted in a significantly lower number of transurethral resections per patient-year in Etretinate-treated patients. However, Etretinate was removed from the US and Canadian markets as it was shown to result in birth defects.

Our recent studies have demonstrated that ATRA is capable of promoting urothelial differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells (ESC) in vitro [76]. In this system, cultivation of ESCs with selective concentrations of RA promoted downregulation of pluripotency factors such as Oct4, with concurrent upregulation of Gata4 and Gata6, Foxa1 (see sections below), UP1a, UP1b, UP2, UP3a, and UP3b mRNA transcripts in compared to spontaneously differentiating controls. Following RA stimulation, pan-uroplakin protein expression was associated with both p63- and cytokeratin (CK) 20-positive cells in discrete aggregating populations of ESC derivatives. In addition, normal human urothelial cells (NHU) cultivated in vitro in the absence of exogenous retinoids express a squamous-associated CK13-, CK14+ phenotype, but revert to a basal/intermediate CK13+, CK14- state upon treatment with the RAR/RXR ligand, 13-cis-retinoic acid [77]. These observations further demonstrate the importance of RAR/RXR pathways for maintenance of a differentiated phenotype and indicate the essential role retinoid pathways play in urothelial differentiation. In addition, they suggest that the development and study of novel RA analogues to promote differentiation and/or induce apoptosis in urothelium is warranted.

PPARγ Signaling Networks

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) is a nuclear hormone receptor and a ligand-activated transcription factor which is an important signaling molecule for urothelial differentiation processes. PPARγ expression has been associated with differentiation of the presumptive urothelium of the mouse urogenital sinus and in the mature urothelium of mice, rabbits and humans [78–81]. PPARγ agonists, such as troglitazone (TZ), in combination with EGFR inhibition have been reported to activate the urothelial differentiation program of NHU cell cultures [50, 51, 82]. In addition, immunohistochemical analysis of PPARγ expression in human bladder urothelium has demonstrated an association between attenuated nuclear localization and increasing histological grade in bladder carcinoma suggesting that loss of PPARγ may be an important step in the progression of bladder cancer [81].

Activation of the PPARγ pathway requires hetero-dimerization of ligand-bound PPARγ with the RXRα to form a transcription factor complex that binds to peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPRE) in the promoters of target genes [83]. Indeed, RXR-specific inhibitors have been shown to attenuate TZ-induced CK13 expression in NHU cell cultures suggesting a cooperative role of PPARγ-RXR signaling in urothelial differentiation processes [82]. Recently, forkhead box A1 (FOXA1; see below) and interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) transcription factors were identified as intermediary signaling molecules involved in PPARγ-mediated activation of uroplakin expression in EGFR-inhibited NHU cell cultures [84]. These factors were induced upon TZ stimulation and formed transcriptional complexes on putative binding sites of UP1a, UP2, and UP3a promoter fragments while knockdown by transient siRNA of either FOXA1 or IRF-1 abrogated PPARγ-induced uroplakin expression. Both IRF-1 and FOXA1 nuclear localization have been reported in situ in human bladder and ureter-derived urothelia [84]. In addition, Foxa1 expression has been shown to be upregulated in murine ESCs during urothelial differentiation in vitro [76] and in vivo [85] suggesting a potential role for this factor in pluripotent cell specification (see FOXA1 section).

Another potential target of PPARγ-dependent signaling in urothelial differentiation also implicated in bladder cancer is KLF4, a member of the Kruppel-like family of transcription factors and a tumor suppressor gene [86, 87]. Ohnishi and colleagues demonstrated robust expression of KLF4 in the developing bladder and in normal urothelial cells, but observed marked downregulation in bladder cancer tissues [88]. Conversely, forced expression of KLF4 in tumor cells attenuated proliferation. These observations, together with results from expression profiling that identified multiple epithelial differentiation-associated genes as KLF4 targets [89] indicates a role for KLF4 in the induction and/or maintenance of urothelial differentiation.

FOXA Family Members

Emerging evidence indicates the Forkhead (FOX) family transcription factors plays an important role in the progression of human bladder cancer. The FOX family of transcription factors consists of 43 members in mammals that are expressed in a tissue-specific manner [90]. The FOXA subfamily consists of the members FOXA1, FOXA2, and FOXA3 that bind to the consensus DNA sequence ((A/C)AA(C/T)), and act to increase the accessibility of other transcription factors to DNA by displacing linker histones from nucleosomes, allowing for chromatin unfolding [91, 92]. Our research groups have extensively explored the role of the FOXA family in urogenital development, differentiation and malignancy (reviewed in [93]) [76, 94–96], and several lines of evidence indicate a central role for FOXA1 in urothelial differentiation [76, 84, 85, 97]. As loss of differentiation is one characteristic of malignancy, we initiated studies aimed at determining the expression patterns of FOXA family members in commonly used human bladder cancer cell lines, and in human bladder tumors. We observed that the relatively differentiated human cancer cell line RT4 maintained robust FOXA1 expression. In addition, UPK expression was correlated with FOXA1 expression in bladder cancer cell lines as well as human bladder tumors. Our studies also showed that while FOXA1 is uniformly expressed in NMIBC, its expression is significantly decreased in MIBC, as well as in high grade (i.e. poorly differentiated) tumors. When FOXA1 staining was correlated to histological subtype, 81% of cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the bladder were negative for FOXA1 staining compared to only 40% of transitional cell carcinomas (TCC). In addition, approximately one quarter of metastatic tumor deposits in lymph nodes dissected from patients with MIBC were negative for FOXA1 expression. The majority of FOXA1 negative lymph node metastases were dissected from patients with pure SCC, strongly supporting a link between SCC and FOXA1 loss. In summary, these findings support a role for FOXA1 in urothelial differentiation and provide the first evidence linking loss of FOXA1 expression with both SCC and TCC subtypes of MIBC [98].

p53/p63/p73 Family

The p53 family comprises 3 members that display a high degree of evolutionary conservation. All 3 genes possess a second intronic promoter that yields N-terminally truncated variants that act as antagonists of the full-length proteins. In spite of the profound effects of p53 loss on cellular transformation, development of p53-null mice proceeded essentially normally, suggesting the existence of related factors that could compensate for loss of p53. Subsequent identification and characterization of p63 and p73 variants, including the development and analysis of mice genetically modified for these isoforms has yielded a wealth of information regarding the redundant and tissue-specific functions of all three family members.

As the most commonly inactivated tumor suppressor in human tumors, it is not surprising that p53 has been functionally linked to the development of urothelial carcinoma, with a majority of bladder cancers displaying alterations in p53 expression [99]. In marked contrast, mutations of p63 and p73 are rare in human tumors with differences in expression level and/or isoform expression appearing to be the dominant events in cancer. Although p53 is best characterized as a classical tumor suppressor, several studies have indicated that p53 can promote differentiation of mouse ESCs through its ability to downregulate expression of pluirpotency factors, such as Nanog [100]. However, despite evidence for a general pro-differentiation function, a direct role for p53 in regulating urothelial cell differentiation specifically has not been demonstrated. Loss of p53 is necessary but not sufficient for development of urothelial tumors, requiring cooperation with oncogenes such as Ha-ras to elicit tumor formation [101]. Moreover, no association has been demonstrated between p53 levels and/or activity and expression of urothelial markers such as uroplakins.

In contrast to p53, p63 has been directly implicated in specification and differentiation of the urothelium. Early studies of p63 indicated enriched expression in the basal cell layer of certain epithelia [102]. A striking feature of p63-null mouse embryos was failure of selected epithelia such as the apical ectodermal ridge and the epidermis to stratify [102, 103]. Subsequent interrogation of the genitourinary tract of p63−/− mice revealed specific defects in several tissues, including the prostate epithelium and the urothelial lining of the bladder and ureters [11, 32]. The urothelial mucosa of bladders from p63−/− mice showed a cuboidal morphology, instead of stratified transitional epithelium [32]. Evaluation of p63−/− mice during embryonic development demonstrated that the single-layered epithelium expressed uroplakin III, a marker of superficial umbrella cells [11]. Subsequent analysis of chimeras indicated that p63−/− cells could contribute to formation of the umbrella cell layer, but not to basal and intermediate layers [11]. These observations indicate that p63 is an important regulator of urothelial cell differentiation, but that its function is dispensable for specification of the superficial cell layer.

p63 has been implicated not only in differentiation of the urothelium, but also in bladder development. p63 expression, predominantly ΔNp63, is evident in urogenital sinus epithelium as early as embryonic day 11.5 where it displays a ventrally-restricted expression pattern [104]. Genetic ablation of ΔNp63 leads to defective development, in part through effects on the mesenchyme as well as the epithelium, consistent with the requirement of bidirectional stromal-epithelial interactions for normal bladder development. Loss of ΔNp63 is associated with marked induction of apoptosis in ventral urogenital tissues as well as reduced induction of genes required for the tissue expansion and smooth muscle differentiation that promote normal bladder morphogenesis. Investigation of p63 target genes identified in other stratified epithelia such as the skin may provide some insight. Silencing of ΔNp63 in keratinocytes led to marked downregulation of the genes encoding members of the claudin family, including claudin-1, -3 and -10 [105]. Claudins are components of intercellular junctions and are essential in maintaining the barrier function of epithelia. Importantly, claudin-3 was identified as a marker of terminal differentiation of urothelial cells [51]. In that study, cells were induced to differentiate by activation of PPARγ and inhibition of the EGFR. Consistent with a functional interaction between p63 and PPAR-mediated signaling, PPARγ agonists have been shown to induce expression of p63 [106]. These findings suggest that the ability of PPARγ to regulate urothelial differentiation may be mediated, at least in part, by p63. Together, these observations emphasize the critical function of p63 in bladder development.

Evaluation of p63 levels in human bladder tumor specimens has yielded conflicting findings due to the existence of multiple p63 variants (TAp63 vs. ΔNp63 and the associated α, β or γ isoforms of each) and the paucity of antibodies that discriminate effectively between them. Although a number of studies have described alterations in p63 expression in bladder tumors versus normal urothelium, not all have demonstrated consistent changes, in part because of the difficulty in ascribing p63-positivity to a specific isoform. By analysis of mRNA levels for TAp63 and ΔNp63 in a cohort of bladder cancers and normal controls, Park and colleagues reported an inverse correlation between TAp63 and ΔNp63. As anticipated from the differentiation-inducing activity of TAp63, levels of this isoform were high in normal bladder tissue and low-grade tumors, whereas ΔNp63 was largely undetectable [107]. However, in high-grade lesions the pattern was reversed, with increasing expression of ΔNp63 and reduced levels of TAp63. In that study, reduced expression of TAp63 was shown to impact patient survival, whereas alterations in ΔNp63 did not. A similar expression pattern was observed when p63 was assessed by immunohistochemical staining [32], although in that study the antibody used for analysis detected both full-length and truncated p63 variants such that the relative expression of ΔNp63 in tumors could not be determined. The development and validation of high-quality isoform-specific antibodies has enabled investigators to better delineate the expression of individual p63 isoforms. In particular, a recent study employed both mouse models and human tumor specimens to assess p63 isoform expression during development and in bladder cancer [12]. Consistent with prior reports, TAp63 was detected in mouse urothelium at embryonic day 16.5, followed by ΔNp63 approximately 24 h after birth. Notably, in contrast to the mouse, no expression of ΔNp63 protein was detected in normal human urothelium. In human bladder cancer tissues, p63 was robustly expressed in non muscle-invasive lesions, with a subset (~15–30%) positive for ΔNp63. Furthermore, the extent of ΔNp63 positivity was further increased in muscle-invasive specimens suggesting an association with ΔNp63 expression and tumor aggressiveness. These findings contrast with a previous study, which concluded that levels of ΔNp63 decrease with bladder cancer progression [108]. In that study, however the focus was only on invasive disease. In agreement with the potential prognostic utility of p63 assessment, Karni-Schmidt and colleagues demonstrated that patients with ΔNp63-positive invasive bladder cancer showed reduced overall survival compared to those whose tumors stained negative for ΔNp63 [12]. Taken together, these findings highlight the need to understand the function of specific p63 isoforms as well as the importance of developing appropriate analytical tools and reagents.

p73, the third p53 family member, has not been widely studied in the context of the urothelium, although it is known to be expressed throughout the normal urothelium, including umbrella cells [109]. Analysis of overall p73 mRNA levels revealed increased expression in invasive bladder cancers compared to normal bladder tissues [110], whereas evaluation of p73 protein levels, specifically the α isoform suggested loss of p73α was associated with tumor progression [109].

Summary and Future Work

As summarized in Figure 2, signals from the microenvironment activate transcriptional networks within urothelial cells to foster differentiation. However, increased efforts need to be placed on understanding how these signals and intracellular pathways are altered in human bladder cancer, and most importantly, their clinical implications. One future area of research will be to identify the transcriptional targets of the factors that are involved in urothelial differentiation. In addition, research is needed to determine the clinical utility of these proteins for use as biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. It is unlikely that any one of these proteins or pathways will serve as independent prognosticators or predictors of outcome. However, analysis of networks or groups of genes/proteins may offer enhanced ability to predict patient outcome, or to identify which patients will benefit from specific clinical approaches, such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy [111]. Finally, basic scientists and clinically trained individuals need to form multidisciplinary teams in order to work on these complex problems.

Figure 2.

Pathways implicated in both urothelial differentiation and neoplastic progression. Biochemical crosstalk between the urothelium and bladder smooth muscle during development and in the mature organ maintains the differentiated phenotype. As discussed in the text, Shh signaling between urothelium and smooth muscle tissue compartments is important in this regard. EGFR and FGFR families and associated ligands have been reported to drive proliferation and inhibit differentiation. Emerging evidence indicates steroid receptor family members, namely RAR, RXR, and PPARγ steroid receptors activate the expression of intermediate transcription factors, including FOXA1 and KLF4. In turn, these factors appear to be important for the activation of gene networks/circuits. It is these networks/circuits that drive and/or maintain urothelial differentiation.

Acknowledgments

DJD was supported by the following funding sources: The American Cancer Society Great Lakes Division-Michigan Cancer Research Fund Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Multidisciplinary Training Grant in Molecular Endocrinology (5 T32 DK007563-21), and the VUMC Integrated Biological Systems Training in Oncology training grant (1 T32 CA119925). The authors wish to acknowledge Simon Hayward for his critical reading of the manuscript. The authors also wish to acknowledge the support of the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network (http://www.bcan.org/), the Bladder Cancer Think Tank and Diane Zipursky Quale for their support. The authors have made every attempt to reference published reports pertinent to this review, and apologize for any oversight in this regard.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Cordon-Cardo C, Cote RJ, Sauter G. Genetic and molecular markers of urothelial premalignancy and malignancy. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2000:82–93. doi: 10.1080/003655900750169338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castillo-Martin M, Domingo-Domenech J, Karni-Schmidt O, Matos T, Cordon-Cardo C. Molecular pathways of urothelial development and bladder tumorigenesis. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:401–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun TT, Zhao H, Provet J, Aebi U, Wu XR. Formation of asymmetric unit membrane during urothelial differentiation. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:3–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00357068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu XR, Kong XP, Pellicer A, Kreibich G, Sun TT. Uroplakins in urothelial biology, function, and disease. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1153–65. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun TT, Liang FX, Wu XR. Uroplakins as markers of urothelial differentiation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;462:7–18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4737-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu XR, Lin JH, Walz T, et al. Mammalian uroplakins. A group of highly conserved urothelial differentiation-related membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13716–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, Mostofi FK. The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1435–48. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy W, Grignon D, Perlman E. Tumors of the Urinary Bladder. In: Silverberg S, Sobin L, editors. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Biology. Washington D.C: 2004. pp. 241–361. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu P, Deng FM, Liang FX, et al. Ablation of uroplakin III gene results in small urothelial plaques, urothelial leakage, and vesicoureteral reflux. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:961–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu P, Meyers S, Liang FX, et al. Role of membrane proteins in permeability barrier function: uroplakin ablation elevates urothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F1200–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00043.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Signoretti S, Pires MM, Lindauer M, et al. p63 regulates commitment to the prostate cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11355–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500165102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karni-Schmidt O, Castillo-Martin M, HuaiShen T, et al. Distinct expression profiles of p63 variants during urothelial development and bladder cancer progression. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1350–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Liu W, Hayward SW, Cunha GR, Baskin LS. Plasticity of the urothelial phenotype: effects of gastro-intestinal mesenchyme/stroma and implications for urinary tract reconstruction. Differentiation. 2000;66:126–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2000.660207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higuchi TT, Granberg CF, Fox JA, Husmann DA. Augmentation cystoplasty and risk of neoplasia: fact, fiction and controversy. J Urol. 2010;184:2492–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soergel TM, Cain MP, Misseri R, Gardner TA, Koch MO, Rink RC. Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder following augmentation cystoplasty for the neuropathic bladder. J Urol. 2004;172:1649–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140194.87974.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Droller MJ. Biological considerations in the assessment of urothelial cancer: a retrospective. Urology. 2005;66:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goebell PJ, Knowles MA. Bladder cancer or bladder cancers? Genetically distinct malignant conditions of the urothelium. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:409–28. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aboseif S, El-Sakka A, Young P, Cunha G. Mesenchymal reprogramming of adult human epithelial differentiation. Differentiation. 1999;65:113–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1999.6520113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunha GR, Chung LW, Shannon JM, Taguchi O, Fujii H. Hormone-induced morphogenesis and growth: role of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1983;39:559–98. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571139-5.50018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiSandro MJ, Li Y, Baskin LS, Hayward S, Cunha G. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in bladder smooth muscle development: epithelial specificity. J Urol. 1998;160:1040–6. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199809020-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donjacour AA, Cunha GR. Induction of prostatic morphology and secretion in urothelium by seminal vesicle mesenchyme. Development. 1995;121:2199–207. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neubauer BL, Chung LW, McCormick KA, Taguchi O, Thompson TC, Cunha GR. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in prostatic development. II. Biochemical observations of prostatic induction by urogenital sinus mesenchyme in epithelium of the adult rodent urinary bladder. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1671–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baskin LS, Sutherland RS, Thomson AA, Hayward SW, Cunha GR. Growth factors and receptors in bladder development and obstruction. Lab Invest. 1996;75:157–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montironi R, Lopez-Beltran A, Scarpelli M, Mazzucchelli R, Cheng L. Morphological classification and definition of benign, preneoplastic and non-invasive neoplastic lesions of the urinary bladder. Histopathology. 2008;53:621–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuter V. WHO Non-invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, high-grade. In: Eble J, Sauter G, Epstein J, Sesterhenn I, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetic Tumors of the Urinary System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. pp. 117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Beltran A, Sauter G, Gasser T, et al. Infiltrating Urothelial Carcinoma. In: Eble J, Sauter G, Epstein J, Sesterhenn I, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of the Urinary System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sesterhen I. WHO Urothelial carcinoma in situ. In: Eble J, Sauter G, Epstein J, Sesterhenn I, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphrey PA. Urinary bladder pathology 2004: an update. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2004;8:380–9. doi: 10.1053/j.anndiagpath.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Rhijn BW, Vis AN, van der Kwast TH, et al. Molecular grading of urothelial cell carcinoma with fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 and MIB-1 is superior to pathologic grade for the prediction of clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1912–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon R, Jones P, Sidransky D, et al. WHO Genetics and predictive factors of non-invasive urothelial neoplasias. In: Eble J, Sauter G, Epstein J, Sesterhenn I, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetic Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. pp. 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urist MJ, Di Como CJ, Lu ML, et al. Loss of p63 expression is associated with tumor progression in bladder cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKenney JK, Desai S, Cohen C, Amin MB. Discriminatory immunohistochemical staining of urothelial carcinoma in situ and non-neoplastic urothelium: an analysis of cytokeratin 20, p53, and CD44 antigens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1074–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harnden P, Eardley I, Joyce AD, Southgate J. Cytokeratin 20 as an objective marker of urothelial dysplasia. Br J Urol. 1996;78:870–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.23511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai S, Lim SD, Jimenez RE, et al. Relationship of cytokeratin 20 and CD44 protein expression with WHO/ISUP grade in pTa and pT1 papillary urothelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:1315–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rotterud R, Nesland JM, Berner A, Fossa SD. Expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor family in normal and malignant urothelium. BJU Int. 2005;95:1344–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amsellem-Ouazana D, Bieche I, Tozlu S, Botto H, Debre B, Lidereau R. Gene expression profiling of ERBB receptors and ligands in human transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 2006;175:1127–32. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thogersen VB, Sorensen BS, Poulsen SS, Orntoft TF, Wolf H, Nexo E. A subclass of HER1 ligands are prognostic markers for survival in bladder cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chow NH, Chan SH, Tzai TS, Ho CL, Liu HS. Expression profiles of ErbB family receptors and prognosis in primary transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1957–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicholson RI, Gee JM, Harper ME. EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(Suppl 4):S9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Memon AA, Sorensen BS, Meldgaard P, Fokdal L, Thykjaer T, Nexo E. The relation between survival and expression of HER1 and HER2 depends on the expression of HER3 and HER4: a study in bladder cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1703–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Memon AA, Sorensen BS, Melgard P, Fokdal L, Thykjaer T, Nexo E. Expression of HER3, HER4 and their ligand heregulin-4 is associated with better survival in bladder cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:2034–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng J, Huang H, Zhang ZT, et al. Overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor in urothelium elicits urothelial hyperplasia and promotes bladder tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adam RM, Danciu T, McLellan DL, et al. A nuclear form of the heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor precursor is a feature of aggressive transitional cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kramer C, Klasmeyer K, Bojar H, Schulz WA, Ackermann R, Grimm MO. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor isoforms and epidermal growth factor receptor/ErbB1 expression in bladder cancer and their relation to clinical outcome. Cancer. 2007;109:2016–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nanba D, Mammoto A, Hashimoto K, Higashiyama S. Proteolytic release of the carboxy-terminal fragment of proHB-EGF causes nuclear export of PLZF. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:489–502. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toki F, Nanba D, Matsuura N, Higashiyama S. Ectodomain shedding of membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF like growth factor and subcellular localization of the C-terminal fragment in the cell cycle. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:839–48. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinugasa Y, Hieda M, Hori M, Higashiyama S. The carboxyl-terminal fragment of pro-HB-EGF reverses Bcl6-mediated gene repression. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14797–806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirata Y, Ogasawara N, Sasaki M, et al. BCL6 degradation caused by the interaction with the C-terminus of pro-HB-EGF induces cyclin D2 expression in gastric cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1320–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varley CL, Stahlschmidt J, Lee WC, et al. Role of PPARgamma and EGFR signalling in the urothelial terminal differentiation programme. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2029–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varley CL, Garthwaite MA, Cross W, Hinley J, Trejdosiewicz LK, Southgate J. PPARgamma-regulated tight junction development during human urothelial cytodifferentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:407–17. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balestreire EM, Apodaca G. Apical epidermal growth factor receptor signaling: regulation of stretch-dependent exocytosis in bladder umbrella cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1312–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baskin LS, Hayward SW, Sutherland RA, DiSandro MS, Thomson AA, Cunha GR. Cellular signaling in the bladder. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d592–5. doi: 10.2741/a215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Rhijn BW, Lurkin I, Radvanyi F, Kirkels WJ, van der Kwast TH, Zwarthoff EC. The fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutation is a strong indicator of superficial bladder cancer with low recurrence rate. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1265–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Rhijn BW, Montironi R, Zwarthoff EC, Jobsis AC, van der Kwast TH. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in urothelial papilloma. J Pathol. 2002;198:245–51. doi: 10.1002/path.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tash JA, David SG, Vaughan EE, Herzlinger DA. Fibroblast growth factor-7 regulates stratification of the bladder urothelium. J Urol. 2001;166:2536–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yi ES, Shabaik AS, Lacey DL, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor causes proliferation of urothelium in vivo. J Urol. 1995;154:1566–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baskin LS, Sutherland RS, Thomson AA, et al. Growth factors in bladder wound healing. J Urol. 1997;157:2388–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haraguchi R, Motoyama J, Sasaki H, et al. Molecular analysis of coordinated bladder and urogenital organ formation by Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2007;134:525–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.02736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tasian G, Cunha G, Baskin L. Smooth muscle differentiation and patterning in the urinary bladder. Differentiation. 2010;80:106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen M, Hildebrandt MA, Clague J, et al. Genetic variations in the sonic hedgehog pathway affect clinical outcomes in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1235–45. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10:940–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ross SA, McCaffery PJ, Drager UC, De Luca LM. Retinoids in embryonal development. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1021–54. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson JG, Warkany J. Malformations in the genito-urinary tract induced by maternal vitamin A deficiency in the rat. Am J Anat. 1948;83:357–407. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000830303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Batourina E, Tsai S, Lambert S, et al. Apoptosis induced by vitamin A signaling is crucial for connecting the ureters to the bladder. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1082–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zou C, Liebert M, Zou C, Grossman HB, Lotan R. Identification of effective retinoids for inhibiting growth and inducing apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. J Urol. 2001;165:986–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boorjian S, Scherr DS, Mongan NP, Zhuang Y, Nanus DM, Gudas LJ. Retinoid receptor mRNA expression profiles in human bladder cancer specimens. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1041–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hurst RE, Waliszewski P, Waliszewska M, et al. Complexity, retinoid-responsive gene networks, and bladder carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;462:449–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4737-2_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molloy CJ, Laskin JD. Effect of retinoid deficiency on keratin expression in mouse bladder. Exp Mol Pathol. 1988;49:128–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(88)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liang FX, Bosland MC, Huang H, et al. Cellular basis of urothelial squamous metaplasia: roles of lineage heterogeneity and cell replacement. The Journal of Cell Biol. 2005;171:835–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Squire RA, Sporn MB, Brown CC, Smith JM, Wenk ML, Springer S. Histopathological evaluation of the inhibition of rat bladder carcinogenesis by 13-cis-retinoic acid. Cancer Res. 1977;37:2930–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grubbs CJ, Moon RC, Squire RA, et al. 13-cis-Retinoic acid: inhibition of bladder carcinogenesis induced in rats by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine. Science. 1977;198:743–4. doi: 10.1126/science.910158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zou C, Zhou J, Qian L, et al. Comparing the effect of ATRA, 4-HPR, and CD437 in bladder cancer cells. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2007–16. doi: 10.2741/1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sabichi AL, Lerner SP, Atkinson EN, et al. Phase III prevention trial of fenretinide in patients with resected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:224–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Studer UE, Jenzer S, Biedermann C, et al. Adjuvant treatment with a vitamin A analogue (etretinate) after transurethral resection of superficial bladder tumors. Final analysis of a prospective, randomized multicenter trial in Switzerland. Eur Urol. 1995;28:284–90. doi: 10.1159/000475068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mauney JR, Ramachandran A, Yu RN, Daley GQ, Adam RM, Estrada CR. All-trans retinoic acid directs urothelial specification of murine embryonic stem cells via GATA4/6 signaling mechanisms. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Southgate J, Hutton KA, Thomas DF, Trejdosiewicz LK. Normal human urothelial cells in vitro: proliferation and induction of stratification. Lab Invest. 1994;71:583–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guan Y, Zhang Y, Davis L, Breyer MD. Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in urinary tract of rabbits and humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F1013–22. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.6.F1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jain S, Pulikuri S, Zhu Y, et al. Differential expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and its coactivators steroid receptor coactivator-1 and PPAR-binding protein PBP in the brown fat, urinary bladder, colon, and breast of the mouse. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:349–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65577-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawakami S, Arai G, Hayashi T, et al. PPARgamma ligands suppress proliferation of human urothelial basal cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2002;191:310–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakashiro KI, Hayashi Y, Kita A, et al. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and its ligands in non-neoplastic and neoplastic human urothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:591–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61730-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Varley CL, Stahlschmidt J, Smith B, Stower M, Southgate J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma reverses squamous metaplasia and induces transitional differentiation in normal human urothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1789–98. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63737-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blanquart C, Barbier O, Fruchart JC, Staels B, Glineur C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: regulation of transcriptional activities and roles in inflammation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;85:267–73. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Varley CL, Bacon EJ, Holder JC, Southgate J. FOXA1 and IRF-1 intermediary transcriptional regulators of PPARgamma-induced urothelial cytodifferentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:103–14. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oottamasathien S, Wang Y, Williams K, et al. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into bladder tissue. Dev Biol. 2007;304:556–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drori S, Girnun GD, Tou L, et al. Hic-5 regulates an epithelial program mediated by PPARgamma. Genes Dev. 2005;19:362–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rageul J, Mottier S, Jarry A, et al. KLF4-dependent, PPARgamma-induced expression of GPA33 in colon cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2802–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ohnishi S, Ohnami S, Laub F, et al. Downregulation and growth inhibitory effect of epithelial-type Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF4, but not KLF5, in bladder cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:251–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen X, Whitney EM, Gao SY, Yang VW. Transcriptional profiling of Kruppel-like factor 4 reveals a function in cell cycle regulation and epithelial differentiation. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:665–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01449-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hannenhalli S, Kaestner KH. The evolution of Fox genes and their role in development and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:233–40. doi: 10.1038/nrg2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cirillo LA, Lin FR, Cuesta I, Friedman D, Jarnik M, Zaret KS. Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol Cell. 2002;9:279–89. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Friedman JR, Kaestner KH. The Foxa family of transcription factors in development and metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2317–28. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.DeGraff DJ, Yu X, Sun Q, et al. The role of Foxa proteins in the regulation of androgen receptor activity. In: Tindall DJ, Mohler JL, editors. Androgen Action in Prostate Cancer. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gao N, Zhang J, Rao MA, et al. The role of hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 alpha (Forkhead Box A1) and androgen receptor in transcriptional regulation of prostatic genes. Molecular endocrinology. 2003;17:1484–507. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gao N, Ishii K, Mirosevich J, et al. Forkhead box A1 regulates prostate ductal morphogenesis and promotes epithelial cell maturation. Development. 2005;132:3431–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.01917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mirosevich J, Gao N, Gupta A, Shappell SB, Jove R, Matusik RJ. Expression and role of Foxa proteins in prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2006;66:1013–28. doi: 10.1002/pros.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thomas JC, Oottamasathien S, Makari JH, et al. Temporal-spatial protein expression in bladder tissue derived from embryonic stem cells. J Urol. 2008;180:1784–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.DeGraff DJ, Clark PE, Cates JM, et al. Loss of Urothelial Differentiation Marker FOXA1 is Associated With High Grade, Late Stage Bladder Cancer and Presence of Squamous Cell Carcinoma. (Under review) [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knowles MA. Molecular subtypes of bladder cancer: Jekyll and Hyde or chalk and cheese? Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:361–73. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin T, Chao C, Saito S, et al. p53 induces differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells by suppressing Nanog expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:165–71. doi: 10.1038/ncb1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gao J, Huang HY, Pak J, et al. p53 deficiency provokes urothelial proliferation and synergizes with activated Ha-ras in promoting urothelial tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:687–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999;398:714–8. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:708–13. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cheng W, Jacobs WB, Zhang JJ, et al. DeltaNp63 plays an anti-apoptotic role in ventral bladder development. Development. 2006;133:4783–92. doi: 10.1242/dev.02621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lopardo T, Lo Iacono N, Marinari B, et al. Claudin-1 is a p63 target gene with a crucial role in epithelial development. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim S, Lee JJ, Heo DS. PPARgamma ligands induce growth inhibition and apoptosis through p63 and p73 in human ovarian cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Park BJ, Lee SJ, Kim JI, et al. Frequent alteration of p63 expression in human primary bladder carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3370–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Koga F, Kawakami S, Fujii Y, et al. Impaired p63 expression associates with poor prognosis and uroplakin III expression in invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5501–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Puig P, Capodieci P, Drobnjak M, et al. p73 Expression in human normal and tumor tissues: loss of p73alpha expression is associated with tumor progression in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5642–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yokomizo A, Mai M, Tindall DJ, et al. Overexpression of the wild type p73 gene in human bladder cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:1629–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith SC, Baras AS, Dancik G, et al. A 20-gene model for molecular nodal staging of bladder cancer: development and prospective assessment. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:137–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70296-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]