Psoriasis is a common immune-mediated, chronic skin disorder with significant impact on Quality of life (QOL) of the patient.[1] The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a commonly used instrument to assess QOL in psoriasis.[2,3] The DLQI consists of 10 patient-rated items with a maximum score of 30. The 10 items are grouped under six headings.[3] Impairments in QOL seem to be associated with the development of psychiatric disorders in psoriasis.[4] Although DLQI scoring is used in a variety of research settings in psoriasis, data regarding the contribution of individual headings to the final score is scarce. We report the results of an analysis of DLQI scores in patients with psoriasis who were then evaluated for presence of any psychiatric disorder. This study was carried out as a part of a larger study that investigated the prevalence and determinants of psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis.

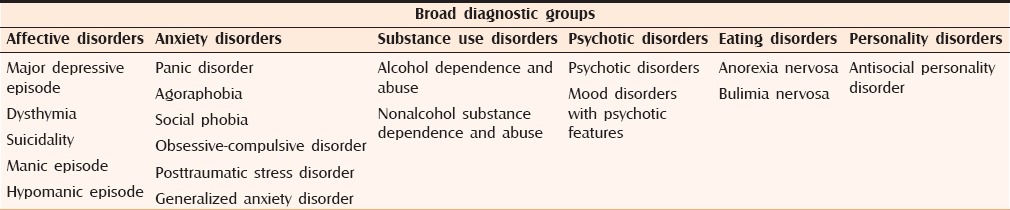

This study was conducted from January to November 2013 in a tertiary care hospital in north India after clearance from the institutional ethics committee. Consecutive patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who provided written informed consent were included in the study. Patients with psoriatic arthritis, erythrodermic and pustular variants of psoriasis were excluded. In the first stage, sociodemographic details were noted and participants were assessed by a dermatologist for clinical details and the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI).[5] Participants were also asked to fill out the DLQI. In the second stage, patients were assessed by a psychiatrist and a psychiatric diagnosis was generated using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [Table 1].[6] Data were then analyzed. using SPSS software (Version 18.0) for Windows. Wald test was used for regression analysis.

Table 1.

Diagnostic groups and diagnoses generated by MINI

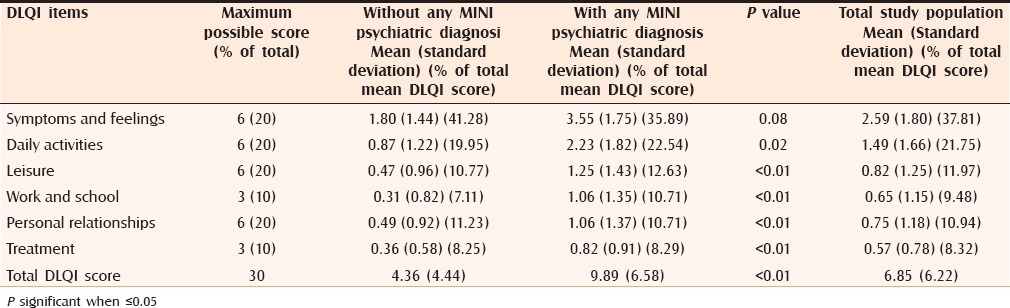

A total of 104 patients (79 males and 25 females) with a mean age of 36.49 years (standard deviation = 13.79) consented to participate in the study. The mean PASI was 6.67 (standard deviation = 6.16) and mean DLQI score was 6.85 (standard deviation 6.22). The PASI and DLQI scores indicate that most patients were suffering from mild-to-moderate psoriasis.[7] Forty-seven patients had at least one MINI diagnosis. Depressive disorders (DD) were the most common diagnoses, prevalence of DD was 39.4% and majority of them had dysthymia (28.84%). About 7% patients had more than one MINI diagnosis. The results of the study are presented in Table 2. A regression analysis (Wald test) with the scores of the different headings as covariates and a positive MINI diagnosis as the dependent variable was carried out. It revealed that the score of the heading of symptoms and feelings predicted a MINI diagnosis (Wald = 8.721, P = 0.003).

Table 2.

Correlation between quality of life and psychiatric comorbidity

The mean scores across each heading of the DLQI and the total were significantly more in the group with any diagnosed psychiatric disorder. However, the percentages of contribution of the mean score of each heading to the total mean DLQI score was not significantly different across the two groups. The percentages of contribution of individual headings show that in our sample, symptoms and feelings contributed most to the total score. On the other hand, the headings of Leisure and Personal relationships were not endorsed as much. Our study suggests that feelings and reactions to the symptoms of disease is the main contributor to impaired QOL in patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis and also predicts psychiatric morbidity. The headings of Daily activities, Work and school, and Treatment “performed as expected.” The results also suggest that impairments in leisure and personal relationships are either not affected as much in mild-to-moderate psoriasis or are deemed to be relatively unimportant. This may be reflective of socioeconomic reasons that prevent many patients in our country to indulge or give due importance to meaningful leisure or sport activities or cultural reasons that prevent sufferers from responding readily to enquiries about sexual issues. Responses on personal or sexual issues are limited by patients because of social prohibitive reasons. It might be interesting to see these responses in more educated patients from urban settings who understand their anonymity and the idea of this being a research tool. In light of the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in this population and the obvious contribution of impairment in QOL to the same, the question of the socioeconomic–cultural applicability of the items used in measurement of QOL becomes important.[8] Our results suggest that emotional reactions to the symptoms of the disease are a major contributor to the impairment in QOL and should be given more importance in QOL measurements. An exploration of QOL in patients with even mild-to-moderate psoriasis is warranted. Although it does not imply that impairment of QOL results in psychiatric comorbidities or vice versa; greater impairments reflected in higher DLQI scores may warrant screening for psychiatric disorders, especially DD. Active management of symptoms and a sympathetic exploration of reactive emotions along with need-based referral to psychiatric services are likely to be important in the improvement of QOL in patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Korte J, Sprangers MA, Mombers FM, Bos JD. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: A systematic literature review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:140–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The dermatology life quality index1994-2007: A comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:997–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)-: A simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: A population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891–5. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langley RG, Ellis CN. Evaluating psoriasis with psoriasis area and severity index, psoriasis global assessment, and lattice system physician's global assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:563–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 4-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, Spuls P, Griffiths CE, Nast A, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: A European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nijsten T. Dermatology life quality index: Time to move forward. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:11–3. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]