Sir,

A 40-year-old man presented with several months history of lesions on his extremities that arose at the sites of insect bite sustained while working as a contractor in Iraq. A recombinant K39 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay done in Iraq was positive. Consequently, he was treated with liposomal Amphotericin B for presumed visceral leishmaniasis. The lesions, however, persisted after he returned to the United States. Examination revealed six 1–2 cm violaceous papulonodules on the right arm and left foot and a 3 cm ulcer on the left calf [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Ulcerated nodule on the left calf with violaceous rolled border

Histopathological study of a lesion demonstrated granulomatous dermatitis with parasitized histiocytes [Figure 2]. A tissue culture on Nicolle–Novy–MacNeal media grew Leishmania major, consistent with cutaneous leishmaniasis. He then received 20 intravenous infusions of sodium stibogluconate with clearance of all lesions. His therapy was complicated by superficial thrombophlebitis of his left leg.

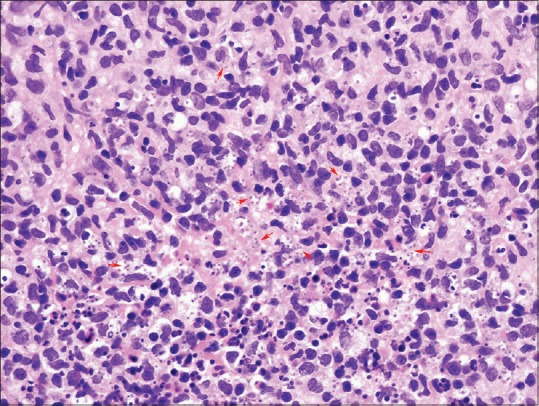

Figure 2.

Granuloma with parasitized histiocytes (intracellular amastigotes at red arrows) (Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×600)

Six months after treatment, he continued to have left leg pain and swelling accompanied by blistering at the site of the erstwhile ulcer. Examination revealed a 3 cm atrophic plaque on the left calf with a fluid-filled blister and mild edema [Figure 3]. A biopsy showed an atrophic partially necrotic epidermis with a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory blister and underlying dermal fibrosis consistent with scar accompanied by scant nongranulomatous lymphoplasmacytic inflammation [Figure 4]. Giemsa staining was negative for amastigotes. Culture and polymerase chain reaction studies were both negative for Leishmania species. Despite Unna boot and compression stocking therapy, recurrent blisters persisted over the scar. Excision and split-thickness skin grafting was performed to remove the scar with no subsequent blisters post-procedure.

Figure 3.

Atrophic scar on the left calf at the site of erstwhile cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion [See Figure 1] with thin overlying fluid-filled blister

Figure 4.

Atrophic partially necrotic epidermis with a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory blister and underlying dermal fibrosis with vertically oriented arcuate-shaped vessels consistent with scar (Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×100)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is estimated to affect 1–1.5 million persons per year worldwide.[1] Old World type localized CL is caused most often by L. major and L. tropica.[1] Patients develop a papule at the site of a sand fly bite, which then enlarges and becomes an ulcerated plaque. Multiple lesions are caused by either multiple bites or sporotrichoid spread along lymphatics. Although CL typically self-resolves, treatment may decrease scarring and prevent dissemination or relapse.[2] L. major is generally thought to have a benign course with most lesions self-resolving within 2–4 months.[3]

Although postinfectious scarring is well known after ulcerated CL, only one report describes chronic lymphedema following treatment of CL and no papers report recurrent blistering within healed scars. Shamsuddin et al. reported that 157 (27%) of 567 patients with CL on the lower legs and feet, had some element of chronic lymphedema in the affected limb following treatment.[4] Of these 157 affected patients, nearly one-fifth had severe lymphedema.[4] Our patient was thoroughly evaluated to look for recurrent infection and the evaluation was negative. We postulate that the ulceration on the lower calf damaged the surrounding lymphatics, causing edema under the atrophic scar and subsequent blistering. The isolated episode of superficial thrombophlebitis alone does not explain why the blister was localized to the scar. Clinicians should be aware of this rare complication of CL involving the lower extremity that can occur even with adequate therapy and may require surgical correction.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis: Current situation and new perspectives. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;27:305–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David CV, Craft N. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:491–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, Saravia NG. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2005;366:1561–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamsuddin S, Mohammed N, Asad F, Nabi H, Ahmad SB. Lymphedema: Another aspect in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2009;19:208–12. [Google Scholar]