Abstract

Observational studies evaluating the relation between dietary or circulating level of beta-carotene and risk of total mortality yielded inconsistent results. We conducted a comprehensive search on publications of PubMed and EMBASE up to 31 March 2016. Random effect models were used to combine the results. Potential publication bias was assessed using Egger’s and Begg’s test. Seven studies that evaluated dietary beta-carotene intake in relation to overall mortality, indicated that a higher intake of beta-carotene was related to a significant lower risk of all-cause mortality (RR for highest vs. lowest group = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.78–0.88) with no evidence of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 1.0%, P = 0.416). A random-effect analysis comprising seven studies showed high beta-carotene level in serum or plasma was associated with a significant lower risk of all-cause mortality (RR for highest vs. lowest group = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.59–0.80) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 37.1%, P = 0.145). No evidence of publication bias was detected by Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests. In conclusion, dietary or circulating beta-carotene was inversely associated with risk of all-cause mortality. More studies should be conducted to clarify the dose-response relationship between beta-carotene and all-cause mortality.

It is widely hypothesized that the beta-carotene rich in green leafy vegetables and other orange-colored plant may prevent oxidative damage1,2. In addition, it is an important pro-vitamin A carotenoid that is metabolized into bioactive vitamin A by the human body3. Therefore, based upon the antioxidant and pro-vitamin A functions of beta-carotene, it is biologically plausible to extend the human life span.

In vitro animal studies have demonstrated that beta-carotene may prevent oxidative damage by counteracting the effects of free radicals4, which is thought to be involved in the pathological process of many chronic diseases. While high dietary intake of beta-carotene has been associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality in observational studies5, the results varied in other studies6,7. Besides, studies assessed the relation between circulating level of beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality yielded inconsistent results8,9,10. Additionally, clinical trials of supplementation with beta-carotene have shown no benefits and discouraging results11. One explanation is that different sources of beta-carotene may generate different influence in its metabolism12. For example, beta-carotene from natural food and supplements may have different influence on human health.

Due to inconclusive data on the effect of dietary beta-carotene intake or circulating beta-carotene levels on risk of all-cause mortality in general healthy population, it is critically important to clarify these associations in general population. Therefore, to evaluate these associations and summarize available observational evidence, we attempted to conduct a meta-analysis of prospective studies on this topic.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

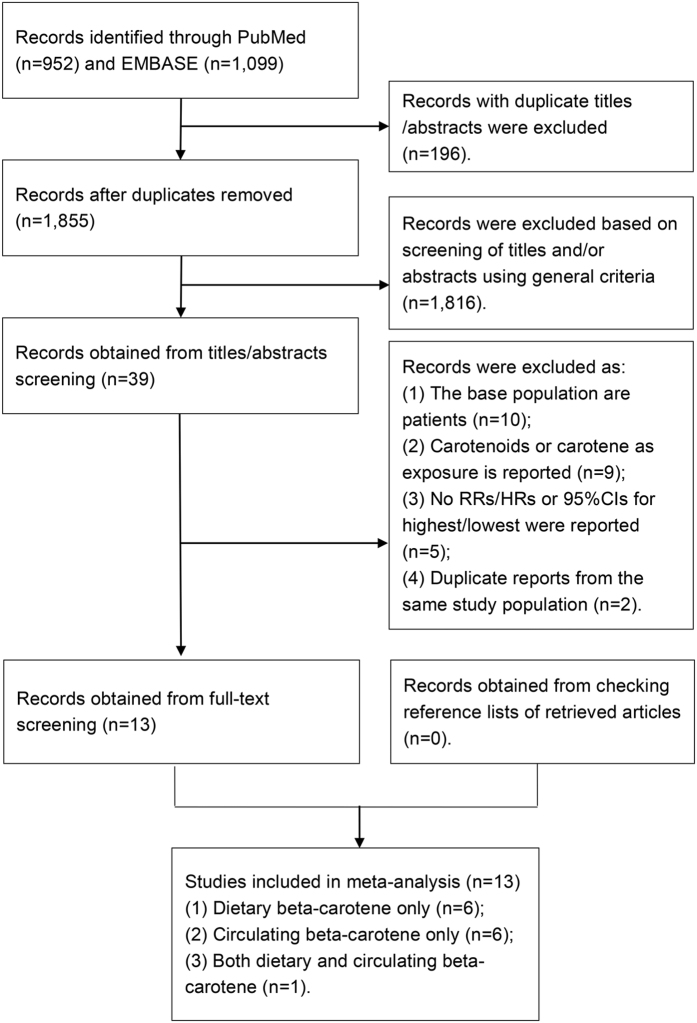

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of search process and results of included studies. We identified 1,855 potentially relevant articles after removal of duplication from our preliminary search of the two databases. Of these, 1,816 were excluded according the inclusion criteria described in the methods section after a review of abstract or title, such as review, animal research and retrospective study, leaving 39 articles for a further full-text review. Among the remaining articles, ten were excluded because they were not conducted in general healthy population. These excluded studies were based on population with specific exposure or health condition, such as certain cancers, patients with obstructive lung function and asbestos-exposed workers. Additionally, nine were removed for taking total carotenoids or carotene as exposure. Two studies9,13 were not considered for duplicate reports from the same study population. Five additional studies14,15,16,17,18 were excluded because we cannot get sufficient data to recalculate the RR or 95%CI for the highest versus lowest group. After exclusion, 13 articles (dietary intake: seven publications; circulating concentration: seven publications)5,6,7,8,10,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 were included in this meta-analysis, of which one study21 reported results for both dietary and circulating level of beta-carotene, respectively.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for selection of studies in meta-analysis of beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality.

RR, relative risk; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 1 showed the characteristics of the 13 included articles. All of these articles were published between 1997 and 2016, consisted of 17,657 deaths among 174,067 participants. The duration of follow-up ranged from two to 25.7 years. Of the included studies, nine were conducted in Europe, two in United States, and two in Japan. Study participants in five studies are only restricted to subjects over 50 years old. All of the studies but one (included only men) included both men and women. All of the studies taking the dietary intake of beta-carotene as an interest exposure used a structured food frequency questionnaires (FFQ), among which the FFQ in four studies had been validated. Only one study5 included beta-carotene from supplements when calculated total beta-carotene consumption. In the seven cohorts focusing the beta-carotene concentration in blood, five tested in serum and two conducted in plasma. The included studies provided the relative risk estimates adjusted for age (13 studies), body mass index (9 studies), smoking status (8 studies), alcohol consumption (8 studies), energy intake (6 studies), physical activity (7 studies), and history of chronic diseases (6 studies).

Table 1. General characteristics of prospective studies of dietary or serum beta-carotene and all-cause mortality (1997–2016).

| No. | First author, year | Country | Cohort or Location | Response rate | Follow-up years | Follow-up rate | Cohort size | No. of death | Baseline age (year) | Exposure measurement | Median | Quantity | Sex | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stepaniak, 2016 | Eastern Europe | HAPIEE study | 59.00% | 7.2 | 95.60% | 26993 | 2371 | 45–69 | Validated FFQ | 7404.7 ug/d | Quintile 5 vs. Q1; 13955.3/3189.5 | Both | Age, country, education, smoking status, alcohol intake, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, history of cadiovascular disease or cancer, total energy intake |

| 2 | Henríquez-Sánchez, 2016 | Spain | PREDIMED study | Not available | 4.3 | 97.20% | 7015 | 319 | M: 55–80 F: 60–80 | Validated FFQ | Not available | Quintile 5 vs. Q1 | Both | Recruitment center, intervention group, age, sex, education, marital status,body mass index, smoking habit, alcohol consumption, total energy intake, energy-adjusted intake of saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids and glycemic index and medical history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and cancer. |

| 3 | Roswall, 2012 | Danmark | DCH study | 35.50% | 13.8 | 100.00% | 55453 | 6767 | 50–64 | Validated FFQ | 3205.4 ug/d | Highest vs. Lowest group; >4798/<1317 | Both | Age, alcohol intake, body mass index, waist circumference, smoking status, smoking duration, smoking intensity, time since cessation, education, and physical activity, vitamin E, vitamin C, folic acid, vitamin supplementation. |

| 4 | Agudo, 2008 | Spain | EPIC-Spain | 55%-60% | 6.5 | 100.00% | 41358 | 562 | 30–69 | Validated dietary histogoty | 1678.6 ug/d | Quartile 4 vs. Q1; 3707.2/830.4 | Both | Age, sex, total energy intake, education, body mass index, physical activity, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption. |

| 5 | Genkinger, 2004 | US | CLUE cohort studies | 86.00% | 12.2 | 97.00% | 6151 | 910 | 30–93 | FFQ | 1697.0 ug/d | Quintile 5 vs. Q1; 3884.8/679.2 | Both | Age, smoking status, body mass index, cholesterol concentration, and energy. |

| 6 | Fletcher, 2003 | UK | Substudy of a randomized trial | 47%(Dietary); 52%(Plasma) | 4.4 | 100.00% | 1175 | 290 | 75–84 | FFQ | 2154 ug/d | Quintile 5 vs. Q1; | Both | Age, sex, total energy intake, body mass index, cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease or cancer, supplement use, physical activity, and housing tenure |

| Plasma | 372 nmol/L | Quintile 5 vs. Q1; 772/153 | Both | Age, sex, body mass index, cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol, diabetes, and history of cardiovascular disease or cancer, physical activity, housing tenure, vitamin supplementation. | ||||||||||

| 7 | Todd, 1999 | UK | SHHS | Not available | 7.7 | 99.90% | 11629 | 591 | 40–59 | FFQ | 2967.7 ug/d | Quartile 4 vs. Q1 | Both | Age, serum total cholesterol, systolic btood pressure, carbon monoxide, energy, previous medical diagnosis of diabetes, body mass index, the Bortner personality score, trigtycerides, high density llpoproteln cholesterol, fSrinogen, a self-reported measure of activity in leisure, and alcohol consumption |

| 8 | Goyal, 2013 | US | NHANES III | 78% | 14.2 | 96.70% | 16008 | 4225 | >20 | Serum | 368 nmol/L | Quintile 5 vs. Q1; >520/<130 | Both | Age, sex, race-ethnicity, level of education, annual family income, body mass index, smoking status, serum cotinine level, alcohol consumption, fruit and vegetable intake, physical activity, serum total cholesterol levels, hypertension status, diabetes status, history of heart attack, congestive heart failure, stroke or cancer, hormone use in women, and supplement use |

| 9 | Bates, 2011 | UK | BNDNs | 99.80% | 13.5 | 94.50% | 1054 | 717 | >65 | Plasma | 363 nmol/L | per SD | Both | Age and sex |

| 10 | Huerta, 2006 | Spain | Asturias | Not available | 4.3 | 96.00% | 154 | 31 | 61.5–79.8 | Serum | 168 nmol/L | Tertile 3 vs. T1; >177.51/<87 | Both | Age, sex, body mass index, self-perceived health, alcohol consumption, practice of daily exercise, diabetes, use of antihypertensive drugs, plasma albumin concentration, plasma lipids. |

| 11 | Ito, 2002 | Japan | CHEP (1990–1994) | Not available | 6–10 | 90.50% | 2444 | 146 | 39–80 | Serum | 455 nmol/L | Tertile 3 vs. T1 | Both | Age, sex, habits of smoking and alcohol consumption, and serum levels of total cholesterol and GPT activity |

| 12 | Kilander, 2001 | Sweden | Uppsala | 82.00% | 22.7–25.7 | 100.00% | 2285 | 630 | 48.6–51.1 | Serum | 302 nmol/L | per SD | Male | Age |

| 13 | Ito, 1997 | Japan | CHEP (1986–1989) | Not available | 2–8 | Not available | 2348 | 98 | 39–83 | Serum | 666 nmol/L | Highest vs. Lowest group; Male, >592/266; Female, 1266/682 | Both | Age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking. |

Abbreviation: FFQ, food frequency questionaire; SD, standard deviation; M, male; F, female.

Dietary intake of beta-carotene and all-cause mortality

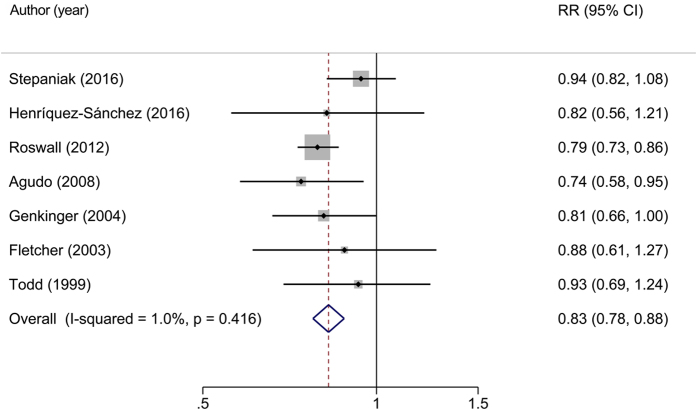

Seven studies5,6,7,19,20,21,22 including 11,810 deaths among 149,774 cohort members were included in the analysis, which indicated that a high intake of beta-carotene was related to a significant reduced risk of all-cause mortality (RR for highest vs. lowest group = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.78–0.88) with no evidence of between study heterogeneity (I2 = 1.0%, P = 0.416) under a random-effect model (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Relative risks of all-cause mortality for highest versus lowest category of dietary intake of beta-carotene.

Overall relative risk calculated with random effects model.

In subgroup analyses, the associations between dietary intake of beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality did not differ substantially by number of participants, age at baseline, measurement type of exposure, median intake and adjustment of energy intake, vitamin supplements use and serum cholesterol level. The exception is that an inverse association was not significant in studies failed to adjust chronic disease history (Table 2).

Table 2. Stratified pooled relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for highest versus lowest category of dietary beta-carotene and all-cause mortality.

| Subgroups | N | Death | Participants | RR | 95%CI | I2 (%) | Pa | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 7 | 11810 | 149774 | 0.83 | 0.78, 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.416 | ||

| Duration of follow-up | 0.144 | ||||||||

| <10 years | 5 | 4133 | 88170 | 0.89 | 0.80, 0.98 | 0 | 0.555 | ||

| > = 10 years | 2 | 7677 | 61604 | 0.79 | 0.73, 0.86 | 0 | 0.826 | ||

| Sample size | 0.902 | ||||||||

| <10,000 | 3 | 1519 | 14341 | 0.83 | 0.70, 0.97 | 0 | 0.928 | ||

| > = 10,000 | 4 | 10291 | 135433 | 0.84 | 0.75, 0.94 | 49.30 | 0.116 | ||

| Population age at baseline | 0.255 | ||||||||

| <50 | 4 | 4434 | 86131 | 0.87 | 0.78, 0.97 | 14.50 | 0.320 | ||

| > = 50 | 3 | 7376 | 63643 | 0.80 | 0.74, 0.86 | 0 | 0.843 | ||

| Median intake | 0.519 | ||||||||

| <2500 ug/d | 3 | 1762 | 48684 | 0.80 | 0.69, 0.92 | 0 | 0.722 | ||

| > = 2500 ug/d | 3 | 9729 | 94075 | 0.86 | 0.75, 0.99 | 60.80 | 0.078 | ||

| Validated FFQ | 0.751 | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 10019 | 130819 | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 42.70 | 0.155 | ||

| No | 3 | 1791 | 18955 | 0.85 | 0.73, 1.00 | 0 | 0.741 | ||

| Major confounders adjusted | |||||||||

| History of disease | 0.071 | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 3571 | 46812 | 0.79 | 0.73, 0.85 | 0 | 0.852 | ||

| No | 3 | 8239 | 102962 | 0.92 | 0.82, 1.03 | 0 | 0.920 | ||

| Smoking and drinking | 0.837 | ||||||||

| Yes | 5 | 10309 | 131994 | 0.83 | 0.76, 0.91 | 25.60 | 0.251 | ||

| No | 2 | 1501 | 17780 | 0.85 | 0.72, 1.00 | 0 | 0.451 | ||

| Physical activity | 0.158 | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 8210 | 109615 | 0.80 | 0.74, 0.86 | 0 | 0.629 | ||

| No | 3 | 3600 | 40159 | 0.89 | 0.80, 1.00 | 0 | 0.457 | ||

| Serum cholesterol level | 0.751 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 1791 | 18955 | 0.85 | 0.73, 1.00 | 0 | 0.741 | ||

| No | 4 | 10019 | 130819 | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 42.70 | 0.155 | ||

| Vitamin supplementation use | 0.302 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2 | 7057 | 56628 | 0.79 | 0.73, 0.86 | 0 | 0.574 | ||

| No | 5 | 4753 | 93146 | 0.87 | 0.79, 0.96 | 0 | 0.461 | ||

Abbreviation: RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; I 2, measure of heterogeneity; Pa, P value for heterogeneity within each group; Pb, P value for heterogeneity between subgroups in meta-regression.

To explore the influence of multi-variables adjustment, several sensitivity analyses were carried out. We conducted the analyses by excluding a study7 that did not adjust for energy intake and a study6 that did not provide information about median or mean intake. Overall, the sensitivity analyses did not lead to any changes in the significance or direction of effect for the association between dietary intake of beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality. Moreover, we removed one study at a time sequentially to reanalysis the data with the risk estimates ranging from 0.80(95%CI: 0.75–0.86) when excluding the study by Stepaniak19, to 0.87(95%CI: 0.80–0.96) after omission of the study by Roswall7. None of the studies considerably affected the summary results.

Circulating level of beta-carotene and all-cause mortality

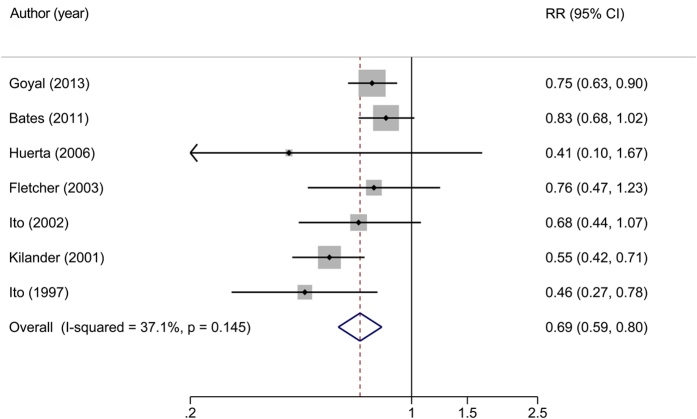

The relation between circulating concentration of beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality was evaluated in seven studies8,10,21,23,24,25,26 comprised 25,468 participants with 6,137 deaths. A random-effect analysis showed a high beta-carotene level in serum or plasma was associated with a significant reduced risk of all-cause mortality (RR for highest vs. lowest group = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.59–0.80) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 37.1%, P = 0.145) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Relative risks of all-cause mortality for highest versus lowest category of circulating level of beta-carotene.

Overall relative risk calculated with random effects model.

Subgroup analyses were performed across a number of key study characteristics (Table 3). The significance of stratified pooled RRs slightly differed when classified by whether adjusting for history of chronic diseases, BMI, physical activity, vitamin supplements use and serum cholesterol level. Stratifications by other characteristics did not have a substantial impact on the major results. In general, results from the meta-regression analysis indicated that no significant heterogeneity was observed between subgroups.

Table 3. Stratified pooled relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for highest versus lowest category of circulating beta-carotene and all-cause mortality.

| Subgroups | n | Death | Participants | RR | 95%CI | I2 (%) | Pa | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 7 | 6137 | 25468 | 0.69 | 0.59, 0.80 | 37.10 | 0.145 | ||

| Duration of follow-up | 0.496 | ||||||||

| < 10 years | 4 | 565 | 6121 | 0.62 | 0.47, 0.82 | 0 | 0.494 | ||

| > = 10 years | 3 | 5572 | 19347 | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.88 | 67.20 | 0.047 | ||

| Sample size | 0.246 | ||||||||

| <2,000 | 3 | 1038 | 2383 | 0.81 | 0.67, 0.97 | 0 | 0.600 | ||

| > = 2,000 | 4 | 5099 | 23085 | 0.63 | 0.51, 0.78 | 46.60 | 0.132 | ||

| Population age at baseline | 0.246 | ||||||||

| <50 | 4 | 5099 | 23085 | 0.63 | 0.51, 0.78 | 46.60 | 0.132 | ||

| > = 50 | 3 | 1038 | 2383 | 0.81 | 0.67, 0.97 | 0 | 0.600 | ||

| Median level | 0.076 | ||||||||

| <350 nmol/L | 2 | 661 | 2439 | 0.54 | 0.42, 0.70 | 0 | 0.688 | ||

| > = 350 nmol/L | 5 | 5476 | 23029 | 0.75 | 0.66, 0.86 | 9.30 | 0.354 | ||

| Blood sample | 0.197 | ||||||||

| Serum | 5 | 5130 | 23239 | 0.63 | 0.52, 0.77 | 34.00 | 0.194 | ||

| Plasma | 2 | 1007 | 2229 | 0.82 | 0.68, 0.99 | 0 | 0.741 | ||

| Major confounders adjusted | |||||||||

| History of disease | 0.560 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 4546 | 17337 | 0.74 | 0.63, 0.88 | 0 | 0.703 | ||

| No | 4 | 1591 | 8131 | 0.64 | 0.49, 0.84 | 63.80 | 0.040 | ||

| Smoking and drinking | 0.962 | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 4759 | 21975 | 0.71 | 0.61, 0.83 | 1.40 | 0.385 | ||

| No | 3 | 1378 | 3493 | 0.66 | 0.46, 0.96 | 69.20 | 0.039 | ||

| BMI | 0.560 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 4546 | 17337 | 0.74 | 0.63, 0.88 | 0 | 0.703 | ||

| No | 4 | 1591 | 8131 | 0.64 | 0.49, 0.84 | 63.80 | 0.040 | ||

| Physical activity | 0.572 | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 4692 | 19781 | 0.74 | 0.63, 0.86 | 0 | 0.839 | ||

| No | 3 | 1445 | 5687 | 0.62 | 0.44, 0.89 | 75.90 | 0.016 | ||

| Serum cholesterol level | 0.471 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 4661 | 19627 | 0.74 | 0.63, 0.87 | 0 | 0.918 | ||

| No | 4 | 1476 | 5841 | 0.61 | 0.44, 0.85 | 65.90 | 0.032 | ||

| Vitamin supplementation use | 0.454 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2 | 4515 | 17183 | 0.75 | 0.64, 0.89 | 0 | 0.960 | ||

| No | 5 | 1622 | 8285 | 0.63 | 0.49, 0.82 | 54.60 | 0.066 | ||

Abbreviation: RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; I 2, measure of heterogeneity; Pa, P value for heterogeneity within each group; Pb, P value for heterogeneity between subgroups in meta-regression.

To further confirm the robustness of the results, we conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding sequentially one study at a time. The pooled risks ranged from a low estimate of 0.67(95%CI: 0.59–0.76) when removing the study by Bates10, to a high estimate of 0.72(95%CI: 0.65–0.81) while omitting the study by Ito25 but were similar in general. In main analyses, we transformed RRs for per standard deviation (SD) into RRs for top versus bottom tertile in two studies10,26. After excluded these two studies, the risk estimates did not change much (RR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.61–0.82, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.458).

Publication bias

In analysis of dietary intake of beta-carotene and all-cause mortality, visual inspection of Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests provided no evidence of publication bias (Begg’s test: P = 0.764; Egger’s test: P = 0.567). Similarly, no publication bias was observed by the funnel plot, Egger’s regression test (P = 0.209), or by Begg’s rank correlation test (P = 0.368) in the meta-analysis on association between circulating concentration of beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality. Funnel plots are provided in supplemental materials (Supplemental Figs 1 and 2).

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, the dietary intake of beta-carotene was inversely associated with risk of all-cause mortality in general population. The association was consistent in subgroup and sensitivity analyses. In addition, the high level of circulating beta-carotene was also associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality. No publication bias was detected in our analyses.

In contrast with results from randomized control trials, we observed a favorable impact of dietary or circulating beta-carotene on risk of all-cause mortality among general population in observational studies. A review11 combining 26 trials reported that the high-dose supplementation of beta-carotene may lead to null or adverse effect on all-cause mortality. The discrepancy between intervention trials and cohort studies may be explained by several reasons. Firstly, beta-carotene in natural or synthetic forms may have difference in bioavailability on risk of all-cause mortality. Natural source of beta-carotene may be due to synergistic interaction with other micronutrients present in non-processed or natural food27,28. Secondly, another explanation is that the dose of beta-carotene supplement used in intervention studies is higher than that in most epidemiological studies. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials indicated that beta-carotene supplements used separately or together with other antioxidants significantly increased mortality in population with doses above the recommended daily allowances. In contrast, non-significantly inverse association was observed in groups below recommended daily allowances29. The underlying mechanism may be the possibility of a U-shaped relation between beta-carotene status and mortality risk8,30,31. From this point of view, in poorly nourished populations, a higher intake of beta-carotene may decrease the risk of all-cause mortality32. While in population with a relatively high nutritional status, the benefits may disappear with additional non-dietary intake. Thirdly, the association we observed may reflect residual confounding from other important dietary ingredients, which is highly related with dietary beta-carotene. However, this cannot be ruled out based on observational studies.

Extensive evidence has demonstrated that dietary beta-carotene had protective effects in preventing non-communicable chronic disease. Recently, results from 37,846 participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Netherlands study indicated that higher dietary intakes of beta-carotene were associated with a reduced diabetes risk33. Additionally, a systematic review demonstrated that evidence from cohort studies supported the protective effects of dietary beta-carotene on preventing cardiovascular disease34. In regard to cancers, some studies suggested that higher intake of dietary beta-carotene could reduce lung35 and colorectal cancer risk36. In a recent Japanese cohort study, high serum carotenoids especially alpha- and beta-carotene and beta-cryptoxanthin were associated with lower risk for the metabolic syndrome37. Therefore, the evidence was consistent with our results dietary or circulating beta-carotene is associated with risk of all-cause mortality.

Biologically, dietary source of beta-carotene may reduce risk of mortality in humans through several mechanisms. Firstly, beta-carotene can play an important role for its pro-vitamin A activity2. It is widely assumed that vitamin A is essential to human body for normal organogenesis, tissue differentiation, immune competence, and maintaining a normal vision38. Actually, based on current evidence, it is obvious that some under nutritional population do not meet the recommendation for vitamin A intake3. Secondly, beta-carotene may exert physiological action by both antioxidant and prooxidant effects. The antioxidant-prooxidant activity of beta-carotene would be dependent on the oxygen tension in human body39. With a low oxygen tension, beta-carotene and other antioxidants can act synergistically as an effective radical-scavenging antioxidant in biological membranes40. The antioxidant properties of beta-carotene seemed to protect against chronic diseases and conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and obesity41,42. Thirdly, beta-carotene may enhance immune cell function to play a major role in the prevention of chronic diseases43.

Strengths of our studies included the large number of both total participants and outcomes. Additionally, the results were stable and robust in subgroup and sensitivity analyses. In current analysis, no evidence of heterogeneity was observed for associations between dietary or circulating beta-carotene and all-cause mortality. However, some limitations of our meta-analysis should be considered. First, observational studies were susceptible to undiscovered confounders, such as unadjusted lifestyle, specific nutrients, et al. Second, the number of studies was limited to draw a firm conclusion. However, on basis of current evidence, beta-carotene from natural food may seem favorable to our body. Third, we did not conduct dose-response analysis for lack of available data even we had tried our best to connect the authors to obtain essential information. Further study should be conducted to explore dose-response relation in general population hereafter.

In summary, the current meta-analysis shows that both dietary intake and circulating level of beta-carotene were inversely associated with the risk of all-cause mortality. More studies should be conducted in various populations with different diet habits to clarify the dose-response relation in order to determine optimal intake for dietary guidance in terms of public health policy and practice.

Methods

Data sources, search strategy, and selection criteria

We followed standard criteria for conducting and reporting of the current meta-analyses44. We conducted a comprehensive publication search in the database of PubMed and EMBASE up to 31 March 2016 for studies assessing the relationship of dietary intake or/and blood concentrations of beta-carotene with all-cause mortality risk. The search terms used were as following: (mortality OR death) AND (antioxidant OR carotenoid OR carotene) AND (cohort studies OR follow-up studies OR longitudinal studies OR prospective studies).

The publication can be included only if it: (1) was a prospective cohort, case-cohort, or nested case-control study conducted in general healthy population, (2) reported dietary intake of beta-carotene or blood beta-carotene concentration as exposure status, (3) presented total mortality as the outcome of interest, (4) provided information about relative risk (RR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) or data necessary to calculate these. In addition, we manually reviewed the references list of all previous reviews, relevant meta-analysis and the studies that were included in this analysis to identify other eligible articles that were not found in preliminary document retrieval. When the studies with same population were published repeatedly, priority was given to the publication with largest number of cases or which with most applicable estimates.

Data collection

Two investigators (Long-Gang Zhao and Qing-Li Zhang) independently reviewed all available studies and extracted data with a standard collection form. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the two authors. The following characteristics in the identified studies were recorded: first author’s last name, year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, study name, study period, response rate, follow-up rate, sample size, total number of death, population age at baseline, method used to assess dietary intake of beta-carotene, median or mean dietary intake or circulating level of beta-carotene, categories of dietary intake of beta-carotene or circulating concentration and the RRs or hazards ratio (HRs) and 95%CIs for all-cause mortality associated with those categories, gender of study population, and covariates included for adjustment in multivariable regression models. If multiple estimates were provided, results with multivariable-adjusted risk estimates that were adjusted for most potential confounding factors in original studies were adopted.

Statistical analysis

For two studies reported the RR for per standard deviation10,26, we translated it into RR for top tertile versus bottom tertile using method introduced by Danesh et al.45. For the studies17,19,22 reported sex-specific results only, we first combined the separate data in a fixed model and then incorporated them with other studies.

In order to examine the association between beta-carotene intake, circulating beta-carotene concentration and risk of all-cause mortality, we calculated pooled RR and 95% CI comparing the highest with the lowest category of beta-carotene intake or blood concentration. We adopted the random-effect model to account for variation between studies proposed by DerSimonian and Laird46. The possible heterogeneity among studies was tested using the Q (χ2) and I2 statistics. Meta-regression was performed to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity between studies. Critical heterogeneity was defined when I2 > 50% or P for Q statistic < 0.1047.

We did not assess study quality but we conducted stratified analysis by such specific study characteristics as duration of follow-up, cohort size, exposure measurement types, population age at baseline, median exposure level and adjustment for confounders (history of chronic disease, smoking status and alcohol consumption, body mass index [BMI], physical activity, vitamin supplements use, serum cholesterol level), which are indicators of study quality. Furthermore, we performed sensitivity analyses by excluding one study at a time to test the influence of individual study on the pooled estimate. Potential publication bias was evaluated by visual inspection of funnel plot and formal testing using Egger’s and Begg’s tests48.

All statistical analyses were carried out with Stata (version 13.0). P values were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05 if not specified.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhao, L.-G. et al. Dietary, circulating beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis from prospective studies. Sci. Rep. 6, 26983; doi: 10.1038/srep26983 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the original studies for the contribution to conduct our meta-analysis. This work was supported by the funds of the State Key Laboratory of Oncogene and Related Genes (No. 91–15–10) and the Shanghai Health Bureau Key Disciplines and Specialties Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.-B.X. obtained the funding, conducted the research design, interpreted the results and also had primary responsibility for the final content. L.-G.Z. and Q.-L.Z. analyzed the data and interpreted the results. L.-G.Z. drafted first manuscript. L.-G.Z., Q.-L.Z., J.-L.Z., H.-L.L., W.Z., W.-G.T. and Y.-B.X. critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved for the submission. No authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Fiedor J. & Burda K. Potential role of carotenoids as antioxidants in human health and disease. Nutrients. 6, 466–488 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber D. & Grune T. The contribution of β-carotene to vitamin A supply of humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 56, 251–258 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grune T. et al. Beta-carotene is an important vitamin A source for humans. J Nutr. 140, 2268S–2285S (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agamey A. et al. Carotenoid radical chemistry and antioxidant/pro-oxidant properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 430, 37–48 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agudo A. et al. Fruit and vegetable intakes, dietary antioxidant nutrients, and total mortality in Spanish adults: findings from the Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Spain). Am J Clin Nutr. 85, 1634–1642 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez-Sanchez P. et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and mortality in the PREDIMED study. Eur J Nutr. 55, 227–236 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roswall N. et al. Micronutrient intake in relation to all-cause mortality in a prospective Danish cohort. Food Nutr Res. 56, 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.5466 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Terry M. B. & Siegel A. B. Serum antioxidant nutrients, vitamin A, and mortality in U.S. Adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 22, 2202–2211 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M. D. et al. Low-serum carotenoid concentrations and carotenoid interactions predict mortality in US adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr Res. 31, 178–189 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates C. J., Hamer M. & Mishra G. D. Redox-modulatory vitamins and minerals that prospectively predict mortality in older British people: The National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over. Br J Nutr. 105, 123–132 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelakovic G., Nikolova D., Gluud L. L., Simonetti R. G. & Gluud C. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, D7176 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donhowe E. G. & Kong F. Beta-carotene: digestion, microencapsulation, and in vitro bioavailability. Food Bioprocess Tech. 7, 338–354 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y. et al. A population-based follow-up study on mortality from cancer or cardiovascular disease and serum carotenoids, retinol and tocopherols in Japanese inhabitants. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 7, 533–546 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey D. K., Shekelle R., Selwyn B. J., Tangney C. & Stamler J. Dietary vitamin C and beta-carotene and risk of death in middle-aged men. The Western Electric Study. Am J Epidemiol. 142, 1269–1278 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karppi J., Laukkanen J. A., Makikallio T. H., Ronkainen K. & Kurl S. Serum beta-carotene and the risk of sudden cardiac death in men: A population-based follow-up study. Atherosclerosis. 226, 172–177 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karppi J., Laukkanen J. A., Makikallio T. H., Ronkainen K. & Kurl S. Low beta-carotene concentrations increase the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality among Finnish men with risk factors. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 22, 921–928 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P. et al. The effects of serum beta-carotene concentration and burden of inflammation on all-cause mortality risk in high-functioning older persons: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 59, 849–854 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waart F. G., Schouten E. G., Stalenhoef A. F. & Kok F. J. Serum carotenoids, alpha-tocopherol and mortality risk in a prospective study among Dutch elderly. Int J Epidemiol. 30, 136–143 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepaniak U. et al. Antioxidant vitamin intake and mortality in three Central and Eastern European urban populations: the HAPIEE study. Eur J Nutr. 55, 547–560 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genkinger J. M., Platz E. A., Hoffman S. C., Comstock G. W. & Helzlsouer K. J. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intake and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality in a community-dwelling population in Washington County, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 160, 1223–1233 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher A. E., Breeze E. & Shetty P. S. Antioxidant vitamins and mortality in older persons: findings from the nutrition add-on study to the medical research council trial of assessment and management of older people in the community. Am J Clin Nutr. 78, 999–1010 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd S., Woodward M., Tunstall-Pedoe H. & Bolton-Smith C. Dietary antioxidant vitamins and fiber in the etiology of cardiovascular disease and all-causes mortality: results from the Scottish Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 150, 1073–1080 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta J. M., Gonzalez S., Fernandez S., Patterson A. M. & Lasheras C. Lipid peroxidation, antioxidant status and survival in institutionalised elderly: a five-year longitudinal study. Free Radic Res. 40, 571–578 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y. et al. Serum antioxidants and subsequent mortality rates of all causes or cancer among rural Japanese inhabitants. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 72, 237–250 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y. et al. Relationship between serum carotenoid levels and cancer death rates in the residents, living in a rural area of Hokkaido, Japan. J Epidemiol. 7, 1–8 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilander L., Berglund L., Boberg M., Vessby B. & Lithell H. Education, lifestyle factors and mortality from cardiovascular disease and cancer. A 25-year follow-up of Swedish 50-year-old men. Int J Epidemiol. 30, 1119–1126 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower V. An apple a day may be safer than vitamins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 100, 770–772 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers T. Nutrition and lung cancer: lessons from the differing effects of foods and supplements. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 177, 470–471 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelakovic G., Nikolova D. & Gluud C. Meta-regression analyses, meta-analyses, and trial sequential analyses of the effects of supplementation with beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E singly or in different combinations on all-cause mortality: do we have evidence for lack of harm? PLos one. 8, e74558 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelakovic G. & Gluud C. Vitamin and mineral supplement use in relation to all-cause mortality in the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 171, 1633–1634 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski M. & Grzegorczyk K. Adverse effects of antioxidative vitamins. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 25, 105–121 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot W. J. et al. Nutrition intervention trials in Linxian, China: supplementation with specific vitamin/mineral combinations, cancer incidence, and disease-specific mortality in the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 85, 1483–1492 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluijs I. et al. Dietary intake of carotenoids and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 25, 376–381 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chun O. & Song W. Plasma and Dietary Antioxidant Status as Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Review of Human Studies. Nutrients. 5, 2969–3004 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N., Su X., Wang Z., Dai B. & Kang J. Association of Dietary Vitamin A and β-Carotene Intake with the Risk of Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 19 Publications. Nutrients. 7, 9309–9324 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S. et al. Carotenoid intake and risk of colorectal adenomas in a cohort of male health professionals. Cancer Cause Control. 24, 705–717 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M., Nakamura M., Ogawa K., Ikoma Y. & Yano M. High serum carotenoids associated with lower risk for the metabolic syndrome and its components among Japanese subjects: Mikkabi cohort study. Br J Nutr. 114, 1674–1682 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer A. & Vyas K. S. A global clinical view on vitamin A and carotenoids. Am J Clin Nutr. 96, 1204S–1206S (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. & Omaye S. T. Antioxidant and prooxidant roles for beta-carotene, alpha-tocopherol and ascorbic acid in human lung cells. Toxicol in vitro. 15, 13–24 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton G. W. & Ingold K. U. Beta-Carotene: an unusual type of lipid antioxidant. Science. 224, 569–573 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox J. K., Ash S. L. & Catignani G. L. Antioxidants and prevention of chronic disease. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 44, 275–295 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knekt P. et al. Antioxidant vitamins and coronary heart disease risk: a pooled analysis of 9 cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 80, 1508–1520 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. A. Effects of carotenoids on human immune function. Proc Nutr Soc. 58, 713–718 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 283, 2008–2012 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh J., Collins R., Appleby P. & Peto R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA. 279, 1477–1482 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R. & Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 7, 177–188 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. & Thompson S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 21, 1539–1558 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey S. G., Schneider M. & Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 315, 629–634 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.