Abstract

Background

Elderly patients with cardiovascular comorbidities are more likely to die before progressing to needing hemodialysis, so deferring their pre-dialysis vascular access (VA) surgery has been suggested. However, recent declines in cardiovascular mortality in the U.S. population may have changed this consideration. We assessed whether there has been a parallel decrease in cardiovascular co-morbidity in elderly chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients undergoing pre-dialysis access surgery, and whether this impacted clinical outcomes after access creation and cardiovascular events after hemodialysis initiation.

Methods

We identified 3,418 elderly patients undergoing pre-dialysis VA creation from 2004-2009, divided them into 3 time cohorts (2004-05, 2006-07 and 2008-09), and assessed their clinical outcomes during 2 years of follow-up.

Results

There was a progressive decrease in patients with history of peripheral vascular disease (66.5 to 59.7%, p<0.005), heart failure (47.0 to 35.8%, p<0.005), and myocardial infarction (6.5 to 3.3%, p<0.001) from 2004-2009. Death before hemodialysis decreased from 17.5 to 12.6%, survival without hemodialysis increased from 14.5 to 19.0%, and hemodialysis initiation remained constant at ~68% (p<0.001). The incidence of death or cardiovascular event in the first year of hemodialysis decreased from 2004-05 to 2008-09 (HR=0.83, 95% CI, 0.69-0.99; p=0.04).

Conclusion

In the context of a changing population from 2004-09, a progressive decrease in cardiovascular comorbidities in elderly CKD patients undergoing pre-dialysis VA surgery was associated with a decrease in death before hemodialysis and cardiovascular events after starting hemodialysis. These insights should be translated into more thoughtful consideration of which elderly patients should undergo pre-dialysis access surgery.

Keywords: End Stage Renal Disease, Hemodialysis, Vascular Access, Arteriovenous Fistula, Arteriovenous Graft

INTRODUCTION

The majority (~70%) of elderly United States patients with advanced CKD receiving a pre-dialysis permanent vascular access initiate hemodialysis within 2 years of access surgery, suggesting that nephrologists are appropriately incorporating patient age in determining the optimal timing of referral of elderly patients for pre-dialysis permanent vascular access placement[1]. Because elderly patients with high cardiovascular co-morbidity are also more likely to die before initiation of dialysis than to start dialysis, deferring vascular access creation in elderly patients with cardiovascular co-morbidity has been suggested. Deaths in patients with CKD are largely driven by cardiovascular co-morbidity[2,3]. However, in the last decade between 2000 and 2010 there has been a substantial decline in cardiovascular mortality observed in both the general adult population and in the hemodialysis population in the U.S[4,5]. The goal of the current study was to investigate whether there was a parallel improvement in cardiovascular comorbidity among a select group of elderly patients with CKD undergoing pre-dialysis access surgery, and whether this trend affected the likelihood of dying before initiating dialysis, survival without initiating dialysis, or initiating dialysis during 2 years of follow-up after VA surgery. To evaluate these questions, we used a large representative U.S. population of elderly CKD patients undergoing pre-dialysis VA creation between 2004 and 2009, and divided them into 3 time cohorts (2004-05, 2006-07 and 2008-09). For each temporal cohort, we assessed the cardiovascular co-morbidities and cardiovascular events prior to VA surgery, as well as cardiovascular events occurring in the first year after dialysis initiation.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Population

A waiver from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Investigational Review Board was obtained before initiating data analysis. Patient consent was not obtained for this study as all information utilized for this study were from national administrative claims data from a random sample of 5% Medicare patients with CKD and data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) rules allow for release of limited data sets with a Data Use Agreement executed with the USRDS Coordinating Center. Data source and patient exclusion criteria were described in detail in our previous paper[1]. To summarize, we identified 3,418 Medicare patients aged 70 and older with an incident vascular access created before dialysis between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 from using a Medicare 5% sample CKD-based cohort,[1]. Our cohort is 70 years and older in order to allow for a 5-year baseline before the index date (similar to one used by Oliver et al.[6]) to ensure a first predialysis vascular access surgery and to collect complete severity of illness and comorbidity information. Specifically, the CKD patient, physician/supplier, and institutional claims were used to obtain hospitalization, surgery, co-morbidities, and outpatient encounters. A 5-year baseline prior to the index date (similar to one used by Oliver et al.[6]) was used to ensure an incident VA surgery and to collect severity of illness and co-morbidity information. Patients were followed from incident VA creation until initiation of dialysis, death or end of 2-year follow-up.

Variables of Interest

Patient demographics (age, gender, and race) were determined from CKD-based cohort patient file. Co-morbidities were determined by one inpatient diagnosis code (either primary or secondary) and/or two outpatient diagnosis codes in the year prior to the index date and included diabetes, cancer, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral vascular disease, cerebral vascular disease, depression, dementia, and amputation. Cardiovascular co-morbidities (e.g., stroke, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure) were identified based on a primary reason for hospitalization during the baseline year. Co-morbidities were selected based upon published literature indicating a substantial influence on mortality among late stage CKD patients[7,8]. We used a comorbidity index developed and validated for dialysis patients, which outperformed the more widely used Charlson Comorbidity Index in both predictive ability and inference[9-11].

Statistical Analysis

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of three temporal cohorts (2004-05, 2006-07, 2008-09) were summarized as frequency (percentage) for categorical data and mean ± SD for numeric data. To evaluate potential differences in medical care received by patients across the three time periods, we calculated outpatient physician and nephrologist visits and hospitalizations per patient-time. We further linked the three temporal cohorts of CKD patients to United States Renal Disease Systems (USRDS) Medical Evidence Form (MEF) to identify patients who initiated dialysis within 2 years of vascular access creation. These patients were followed from dialysis initiation for one year to calculate a composite end-point of death or cardiovascular events, or the end of follow-up. Patients’ acute cardiovascular events including congestive heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke were obtained from USRDS institutional claims by using International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) codes as follows: CHF (“402×1”, “404×1”, “404×3”, “422”, “425”, “428”, and “V421”), MI (“410”), and stroke (“430” to “434”). Survival at 180 and 360 days after dialysis initiation was examined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and compared across three time periods. A composite endpoint of a cardiovascular event or mortality, whichever came first, was also calculated. All the analyses were conducted by SAS version 9.2.

RESULTS

Temporal Trends in Patient Characteristics and Comorbidities

During the six-year period between 1/1/2004-12/31/2009, 3,418 elderly (age ≥70 years) CKD patients from the 5% Medicare sample received an AVF or AVG before initiating dialysis (Table 1A/B). The mean age of study patients was 78.0 years. The majority of patients were male (54.0%) and white (74.7%), and a substantial proportion had diabetes (66.2%), ischemic heart disease (64.6%), peripheral vascular disease (PVD) (63.4%) and congestive heart failure (CHF) (40.6%). Among elderly patients who received a pre-dialysis vascular access, there was a progressive decrease in patients with history of PVD (66.5 to 59.7%, p<0.005), CHF (47.0 to 35.8%, p<0.005), and myocardial infarction (MI) (6.5 to 3.3%, p<0.001) between the three time cohorts (2004-05, 2006-07, and 2008-09). The decrease in cardiovascular co-morbidities in the 3 time periods was greater in patients age >80 years than in those ages 70-80 years. Specifically, the relative decrease in stroke (40 vs 10%), myocardial infarction (52 vs 47%) and CHF (26 vs 23%) and comorbidity score (10 vs 1%) was consistently greater in the older patient cohort (Table 1A). All other demographics and comorbidities were similar between the three time cohorts (Table 1A/B).

TABLE 1A.

Temporal trend of demographics and co-morbidities in elderly patients with CKD after first vascular access (VA) insertion.

| Year of VA insertion | All | Age 70-80 | Age 80+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study cohort | 3,418 | 2,131 | 1,287 | |

| Age | ||||

| Mean±SD | 2004-2005 | 78.0±5.4 | 74.6±2.9 | 83.9±3.2 |

| 2006-2007 | 78.1±5.4 | 74.6±2.9 | 83.9±3.2 | |

| 2008-2009 | 78.1±5.4 | 74.4±2.9 | 83.8±3.1 | |

| Black | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 196(16.6) | 131(17.4) | 65(15.4) | |

| 2006-2007 | 227(18.6) | 160(21.1) | 67(14.5) | |

| 2008-2009 | 174(17.1) | 123(20.0) | 51(12.7) | |

| Comorbidity score | ||||

| Mean±SD | 2004-2005 | 8.5±4.5 | 8.1±4.5 | 9.1±4.5 |

| 2006-2007 | 8.0±4.3 | 8.0±4.3 | 8.0±4.4 | |

| 2008-2009 | 8.0±4.5 | 8.0±4.5 | 8.2±4.4 | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 764(64.9) | 532(70.5) | 232(54.8) | |

| 2006-2007 | 806(66.0) | 543(71.4) | 263(56.9) | |

| 2008-2009 | 693(68.1) | 439(71.3) | 254(63.2) | |

| Hypertension | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 993(84.3) | 632(83.7) | 361(85.3) | |

| 2006-2007 | 992(81.2) | 624(82.1) | 368(79.7) | |

| 2008-2009 | 781(76.7) | 471(76.5) | 310(77.1) | |

| Stroke | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 50(4.2) | 31(4.1) | 19(4.5) | |

| 2006-2007 | 45(3.7) | 26(3.4) | 19(4.1) | |

| 2008-2009 | 34(3.3) | 23(3.7) | 11(2.7) | |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 76(6.5) | 45(6.0) | 31(7.3) | |

| 2006-2007 | 50(4.1) | 34(4.5) | 16(3.5) | |

| 2008-2009 | 34(3.3) | 20(3.2) | 14(3.5) | |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 554(47.0) | 345(45.7) | 209(49.4) | |

| 2006-2007 | 470(38.5) | 292(38.4) | 178(38.5) | |

| 2008-2009 | 364(35.8) | 217(35.2) | 147(36.6) |

Cohort was followed for 2 years after first VA insertion until death, initiation of dialysis or end of follow-up. For continuous variable, values presented as mean and standard deviation; For categorical variable, values in column 2 are number of patients and percent of the total study cohort of the year.

Table 1B.

Temporal trend of demographics and co-morbidities in elderly patients with CKD after first vascular access (VA) insertion.

| Year of VA insertion | All | Age 70-80 | Age 80+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study cohort | 3,418 | 2,131 | 1,287 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 779(66.1) | 493(65.3) | 286(67.6) | |

| 2006-2007 | 785(64.2) | 488(64.2) | 297(64.3) | |

| 2008-2009 | 644(63.3) | 378(61.4) | 266(66.2) | |

| COPD | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 436(37.0) | 276(36.6) | 160(37.8) | |

| 2006-2007 | 462(37.8) | 296(38.9) | 166(35.9) | |

| 2008-2009 | 385(37.8) | 243(39.4) | 142(35.3) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 783(66.5) | 486(64.4) | 297(70.2) | |

| 2006-2007 | 777(63.6) | 487(64.1) | 290(62.8) | |

| 2008-2009 | 608(59.7) | 355(57.6) | 253(62.9) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 483(41) | 291(38.5) | 192(45.4) | |

| 2006-2007 | 472(38.6) | 289(38.0) | 183(39.6) | |

| 2008-2009 | 413(40.6) | 255(41.4) | 158(39.3) | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 705(59.8) | 470(62.3) | 235(55.6) | |

| 2006-2007 | 780(63.8) | 505(66.4) | 275(59.5) | |

| 2008-2009 | 639(62.8) | 390(63.3) | 249(61.9) | |

| Depression | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 138(11.7) | 100(13.2) | 38(9) | |

| 2006-2007 | 162(13.3) | 104(13.7) | 58(12.6) | |

| 2008-2009 | 123(12.1) | 79(12.8) | 44(10.9) | |

| Dementia | ||||

| 2004-2005 | 104(8.8) | 65(8.6) | 39(9.2) | |

| 2006-2007 | 147(12.0) | 92(12.1) | 55(11.9) | |

| 2008-2009 | 105(10.3) | 65(10.6) | 40(10) |

Cohort was followed for 2 years after first VA insertion until death, initiation of dialysis or end of follow-up. For continuous variable, values presented as mean and standard deviation; For categorical variable, values in column 2 are number of patients and percent of the total study cohort of the year. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Temporal Trends in Clinical Outcomes Before Initiation of Hemodialysis

During the 3 consecutive time periods (2004-05, 2006-07, and 2008-09), the proportion of elderly patients dying before initiating hemodialysis decreased from 17.5 to 12.6%, the proportion surviving without hemodialysis increased from 14.5 to 19.0%, and the proportion initiating hemodialysis remained constant at ~68% (p<0.001)(Table 2). We also evaluated rates of hospitalization and outpatient visits per patient-year among elderly CKD patients after pre-dialysis vascular access was placed. Overall, there was no difference in rates of hospitalization, outpatient physician visits, or nephrology visits between the three time cohorts (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Temporal trend of clinical outcomes in elderly patients with CKD after first vascular access (VA) insertion stratified by year of VA insertion and by age subgroups

| Cohort | Initiated dialysis within 2 yrs | Died before dialysis | Survived and no dialysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full cohort (n=3,418) | |||

| 2004-2005 | 801 (68.0) | 206 (17.5) | 171 (14.5) |

| 2006-2007 | 806 (66.0) | 181 (14.8) | 235 (19.2) |

| 2008-2009 | 697 (68.5) | 128 (12.6) | 193 (19.0) |

| Age 70-80 yr (n=2,131) | |||

| 2004-2005 | 522 (69.1) | 119 (15.8) | 114 (15.1) |

| 2006-2007 | 508 (66.8) | 103 (13.6) | 149 (19.6) |

| 2008-2009 | 432 (70.1) | 65 (10.6) | 119 (19.3) |

| Age 80+ yr (n=1,287) | |||

| 2004-2005 | 279 (66.0) | 87 (20.6) | 57 (13.5) |

| 2006-2007 | 298 (64.5) | 78 (16.9) | 86 (18.6) |

| 2008-2009 | 265 (65.9) | 63 (15.7) | 74 (18.4) |

Values presented as number of patients and row percentage in parenthesis.

P<0.001 for full cohort; p=0.01 for age 70-80 yr; p=0.11 for age 80+ indicating differences between all three time periods.

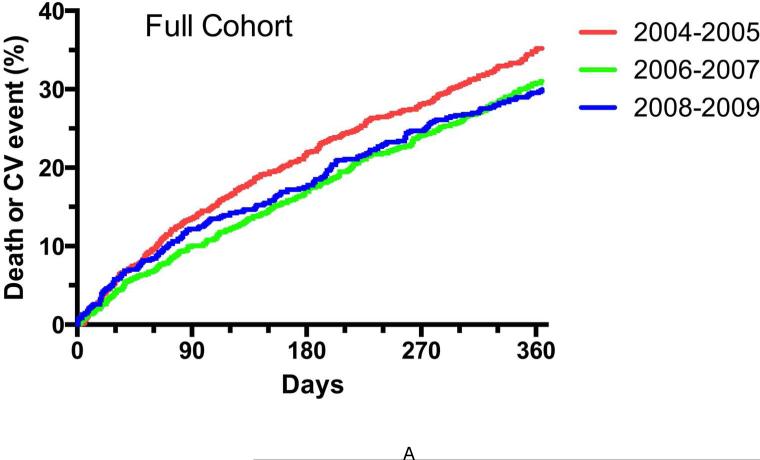

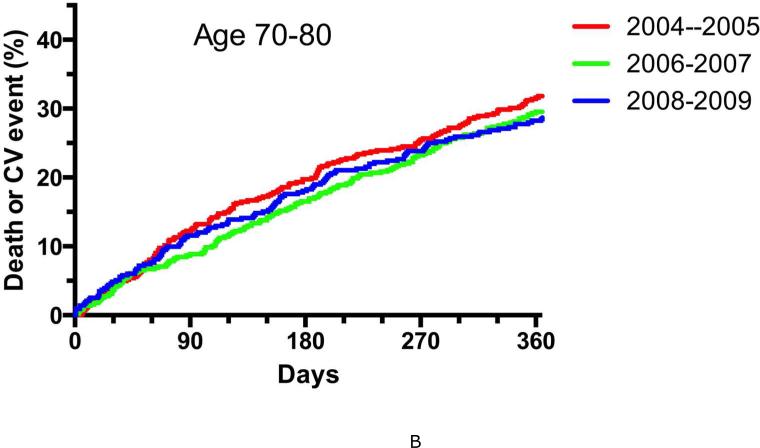

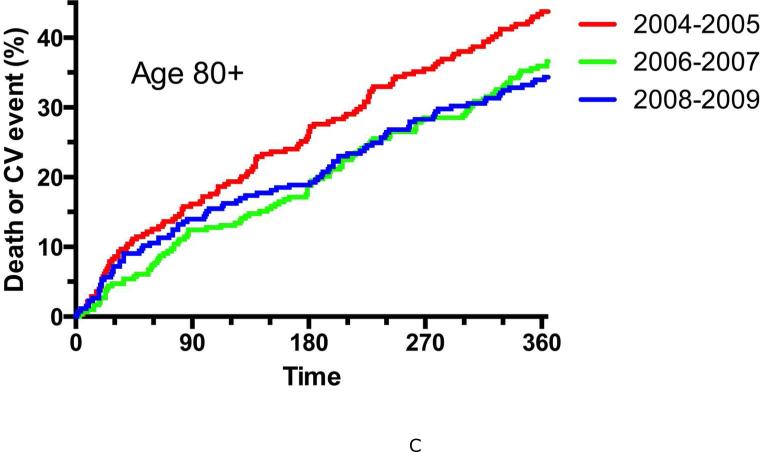

Temporal Trends in Outcomes among Elderly Patients with Pre-Dialysis Vascular Access Placement Initiating Hemodialysis

Table 3 summarizes the mortality of elderly patients with pre-dialysis vascular access placement who initiated hemodialysis from 2004-2009. For the overall cohort, there was a non-significant decrease in patient mortality at 180 and 360 days after initiation of dialysis between the three time periods. However, mortality differences were evident when the patients were subdivided into two age ranges; the one-year mortality decreased by a non-significant 3% in patients ages 70-80 years, but decreased by 27% in those >80 years (p<0.05). Between 2004-05 and 2008-09 the proportion of patients with a new CHF event during the first year of dialysis decreased by 28%, from 10.7 to 7.7% (p=0.047), and the proportion with the composite endpoint of death or a new cardiovascular event (CHF, MI or CVA) decreased by 15%, from 35.2 to 30.0% (p=0.03). Finally, the cumulative incidence of death or cardiovascular event was substantially reduced from 2004-05 to 2008-09 (HR=0.83, 95% CI, 0.69-0.99; p=0.04) in the overall cohort (Figure 1A). When stratified by age, 70-80 (Figure 1B) and >80 years (Figure 1C), only age >80 years demonstrated substantially reduced incidence of death or cardiovascular event (HR 0.74, 95% CI, 0.56-0.97; p=0.03).

TABLE 3.

Proportion of patients dying within 180 and 360 days after dialysis initiation, stratified by year of vascular access (VA) insertion and by age subgroups.

| Cohort | Dialysis Patients (N) | Death, N (%) at 180 days | Death, N (%) at 360 days |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Cohort | |||

| 2004-2005 | 801 | 111(13.9) | 197 (24.6) |

| 2006-2007 | 806 | 87 (10.8) | 177 (22.0) |

| 2008-2009 | 697 | 86 (12.3) | 148 (21.2) |

| Age 70-80 yr | |||

| 2004-2005 | 522 | 57 (10.9) | 103 (19.7) |

| 2006-2007 | 508 | 47 (9.3) | 100 (19.7) |

| 2008-2009 | 432 | 48 (11.1) | 83 (19.2) |

| Age 80+yr | |||

| 2004-2005 | 279 | 54 (19.4) | 94 (33.7) |

| 2006-2007 | 298 | 40 (13.4) | 77 (25.8)* |

| 2008-2009 | 265 | 38 (14.3) | 65 (24.5)* |

p<0.05 vs 2004-2005

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curve of composite endpoint (death or cardiovascular event) for elderly CKD patients who initiated dialysis by the year of vascular access (VA) insertion.

A. Full patient cohort. The cumulative incidence of death or cardiovascular event was substantially reduced from 2004-05 to 2008-09 (HR=0.83, 95% CI, 0.69-0.99; p=0.04). B. Age 70-80 years. The cumulative incidence of death or cardiovascular event was similar from 2004-2005 to 2008-2009 (HR 0.89, 95% CI, 0.71-1.12; p=0.33). C. Age >80 years. The cumulative incidence of death or cardiovascular event was substantially reduced from 2004-2005 to 2008-2009 (HR 0.74, 95% CI, 0.56-0.97; p=0.03).

DISCUSSION

We have identified a trend over a six-year period (from 2004 to 2009) of improving cardiovascular comorbidity among a select group of elderly CKD patients undergoing pre-dialysis vascular access that was reflected in a smaller proportion of patients with a history of peripheral vascular disease, heart failure or myocardial infarction. In our study this trend seemed to be driven by the improved cardiovascular outcomes in patients age >80 years. To our knowledge, secular changes in cardiovascular health have not been previously reported among the CKD predialysis population. As one might expect, the lower cardiovascular comorbidities in this population translated into improved clinical outcomes after access creation, namely fewer patients dying before dialysis and more patients surviving without requiring initiation of dialysis.

What might account for such a large improvement in the cardiovascular comorbidities of this population over a relatively short time period? The most likely explanation is that the improvement in cardiovascular comorbidities among elderly CKD patients undergoing pre-dialysis access surgery simply mirrors that observed in the overall U.S. population. Cardiovascular mortality declined by 30.8% from 2001 to 2011 among the general adult U.S. population, a change that has been attributed to smoking cessation, better blood pressure control, and more widespread use of statins [4]. There was a similar sharp decrease in cardiovascular death among ESRD patients in the U.S. during the same time period[12]. Specifically, according to the USRDS, unadjusted cardiovascular mortality rates among prevalent ESRD patients declined from 81.9 to 64.1 deaths per 1,000 patient years at risk for the overall population and from 2004 to 2008 and from 198.9 to 152.5 for patients 75 years and older[12]. In our study we observed a 17% reduction in risk of death or CV events in the first year of dialysis. In fact, our study suggests that the most significant improvement in the incidence of death or cardiovascular event in the first year of hemodialysis decreased substantially from 2004-05 to 2008-09 in the most elderly patients, that is those patients age >80 years.

We also postulated that better medical care in the current study population would be reflected in more frequent outpatient physician visits (with nephrologists or other physicians) or less frequent hospitalizations after undergoing vascular access surgery. This hypothesis was not supported by our data. However, our database does not include more specific medical interventions prescribed during these visits or hospitalizations (e.g., blood pressure control, use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs, diabetic control, prescription of statins).

A less likely explanation for the improvement of cardiovascular comorbidities among elderly CKD patients undergoing pre-dialysis access surgery is that nephrologists are preferentially referring for pre-dialysis access surgery those patients with less cardiovascular morbidity. Testing this hypothesis would require a comparison of cardiovascular comorbidity in elderly CKD patients with and without pre-dialysis access surgery. Unfortunately, the database we utilized lacks information about kidney function. As a consequence, we did not have a suitable control group. Furthermore, supportive care may be another issue for not considering preemptive access in elderly advanced CKD patients. In recent years there has been a concerted emphasis on patient-centered and shared decision making for our elderly advanced CKD patients[13-15], which may impact our thought process when considering pre-emptive vascular access placement in this group. In other words, because dialysis may not confer survival benefit in certain groups of elderly patients with comorbid conditions, excluding them from consideration for preemptive vascular access placement is a reasonable approach.

A number of previous studies have reported that patients with advanced CKD are significantly more likely to die than to reach ESRD and initiate dialysis during follow-up after a vascular access surgery[16-18]. The likelihood of dying before reaching ESRD and not initiating dialysis is particularly high in elderly patients with CKD, and still higher in those with substantial cardiovascular co-morbidity[16]. However, the more likely a patient is to die before reaching ESRD and not needing dialysis, the more compelling the justification for withholding pre-dialysis access surgery. If elderly CKD patients are progressively having less cardiovascular comorbidities, it may be that a larger proportion should appropriately be considered for pre-dialysis access surgery, as they are less likely to die before progressing to the need for hemodialysis.

A major strength of the present study is the use of a nationally representative random sample of elderly patients with advanced CKD. This allows one to generalize the findings with a high degree of confidence to individual medical centers. Our study also has several limitations. First, we do not have information on the total number of elderly patients potentially eligible for pre-dialysis access surgery, so we cannot examine temporal changes in CVD for patients not selected for VA surgery. Second, we do not have documentation of the reason that a particular elderly patient with CKD was not referred for pre-dialysis access surgery. Thus, we can only infer that the nephrologist or surgeon deemed a given patient to be a poor candidate for pre-dialysis access surgery. However, there may be alternative reasons, such as patient refusal to undergo access surgery prior to starting dialysis. In the first two reasons discussed above selection bias may be a possible explanation for improved level of cardiovascular comorbidities in elderly patients receiving pre-emptive permanent access. However, data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has shown a steady decline in age-adjusted death rates for cardiovascular disease in the general medical population in the United States during the time period of our cohort[19]. While the data do not specifically look at elderly CKD patients, we may also be seeing a similar trend in this population as well. Finally, our data are limited to a period of six years, and we don't know whether the trends described in this study began prior to 2004 or continued after 2009. If, in fact, the progressive improvements in cardiovascular comorbidities continued after 2009, as was the case among the general US population[4,19], this lends enhanced credence to our conclusion that more elderly patients should be deemed eligible for vascular access surgery before dialysis.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the observations in the current study show that among elderly patients with advanced CKD patients undergoing pre-dialysis vascular access placement, the cardiovascular comorbidities has decreased progressively from 2004 to 2009. Consequently, these patients are now less likely to die before dialysis initiation, more likely to survive without ESRD, and equally likely to start HD within 2 years of access surgery. Because they are healthier, these patients are also less likely to have cardiovascular events after starting dialysis. These insights should be translated into more thoughtful consideration of which elderly patients should undergo pre-dialysis access surgery. Thus, our observations from this study suggest that for a select group of elderly CKD patients without significant cardiovascular comorbidities, increased placement of pre-dialysis vascular accesses may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

Support and Financial Disclosures

Dr. Lee is supported by an American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Scholar Grant, University of Alabama at Birmingham Nephrology Research Center Anderson Innovation Award, and University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for Clinical and Translational Science Multidisciplinary Pilot Award (1UL1TR001417-01). Dr. Lee is a consultant for Proteon Therapeutics.

Dr. Allon is supported by grant 1R21DK104248-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). He is also a consultant for CorMedix and Gore.

Dr. Thamer is supported by grant 1R21DK104248-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Dr. Thamer is a consultant for Protoen Therapeutics. Dr. Zhang and Ms. Zhang are supported by grant 1R21DK104248-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and R03-HS-022931 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and have no financial disclosures to report.

Footnotes

This manuscript was presented in abstract form at the 2015 American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week, San Diego, CA November 3-8.

Disclaimer

The data reported herein have been supplied by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors, and in no way should be construed as the official policy or interpretation of the US government.

References

- 1.Lee T, Thamer M, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Allon M. Outcomes of elderly patients after predialysis vascular access creation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014090938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, Parfrey P, Pfeffer M, Raij L, Spinosa DJ, Wilson PW, American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease HBPRCC, Epidemiology, Prevention Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the american heart association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Circulation. 2003;108:2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, McAlister F, Garg AX. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2034–2047. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, Chavers BM, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, Kasiske BL, Liu J, Mau LW, McBean M, Murray A, St Peter W, Guo H, Li Q, Li S, Li S, Peng Y, Qiu Y, Roberts T, Skeans M, Snyder J, Solid C, Wang C, Weinhandl E, Zaun D, Arko C, Chen SC, Dalleska F, Daniels F, Dunning S, Ebben J, Frazier E, Hanzlik C, Johnson R, Sheets D, Wang X, Forrest B, Constantini E, Everson S, Eggers PW, Agodoa L. Excerpts from the us renal data system 2009 annual data report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:S1–420, A426-427. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver MJ, Quinn RR, Garg AX, Kim SJ, Wald R, Paterson JM. Likelihood of starting dialysis after incident fistula creation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:466–471. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08920811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gullion CM, Keith DS, Nichols GA, Smith DH. Impact of comorbidities on mortality in managed care patients with ckd. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:212–220. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens LA, Li S, Wang C, Huang C, Becker BN, Bomback AS, Brown WW, Burrows NR, Jurkovitz CT, McFarlane SI, Norris KC, Shlipak M, Whaley-Connell AT, Chen SC, Bakris GL, McCullough PA. Prevalence of ckd and comorbid illness in elderly patients in the united states: Results from the kidney early evaluation program (keep). Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:S23–33. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Huang Z, Gilbertson DT, Foley RN, Collins AJ. An improved comorbidity index for outcome analyses among dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;77:141–151. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seliger SL. Comorbidity and confounding in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2010;77:83–85. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, Chavers B, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, Kasiske B, Liu J, Mau LW, McBean M, Murray A, St Peter W, Guo H, Gustafson S, Li Q, Li S, Peng Y, Qiu Y, Roberts T, Skeans M, Snyder J, Solid C, Wang C, Weinhandl E, Zaun D, Arko C, Chen SC, Dalleska F, Daniels F, Dunning S, Ebben J, Frazier E, Hanzlik C, Johnson R, Sheets D, Wang X, Forrest B, Constantini E, Everson S, Eggers P, Agodoa L. Us renal data system 2010 annual data report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:A8, e1–526. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Hare AM, Armistead N, Schrag WL, Diamond L, Moss AH. Patient-centered care: An opportunity to accomplish the “three aims” of the national quality strategy in the medicare esrd program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2189–2194. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01930214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandecasteele SJ, Kurella Tamura M. A patient-centered vision of care for esrd: Dialysis as a bridging treatment or as a final destination? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1647–1651. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drew DA, Lok CE. Strategies for planning the optimal dialysis access for an individual patient. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:314–320. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000444815.49755.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins AJ, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Liu J, Chen SC, Herzog CA. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease in the medicare population. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003:S24–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s87.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalrymple LS, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Stehman-Breen C, Seliger S, Siscovick D, Newman AB, Fried L. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of end-stage renal disease versus death. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1511-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, Chavers B, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, Kasiske B, Liu J, Mau LW, McBean M, Murray A, St Peter W, Guo H, Li Q, Li S, Peng Y, Qiu Y, Roberts T, Skeans M, Snyder J, Solid C, Wang C, Weinhandl E, Zaun D, Arko C, Chen SC, Dalleska F, Daniels F, Dunning S, Ebben J, Frazier E, Hanzlik C, Johnson R, Sheets D, Wang X, Forrest B, Constantini E, Everson S, Eggers P, Agodoa L. United states renal data system 2008 annual data report abstract. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:vi–vii, S8-374. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Health NH, Lung, and Blood Institute Morbidity and Mortality: 2012 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. Feb, 2012.