Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling has recently been implicated in the development of cardiac hypertrophy after long-term endurance training, via mechanisms that may involve energetic stress. Given the potential overlap of insulin and IGF-1 signaling we sought to determine if both signaling pathways could contribute to exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy following shorter-term exercise training. Studies were performed in mice with cardiac-specific IGF-1 receptor (IGF1R) knockout (CIGFRKO), mice with cardiac-specific insulin receptor (IR) knockout (CIRKO), CIGFRKO mice that lacked one IR allele in cardiomyocytes (IGFR−/−IR+/−), and CIRKO mice that lacked one IGF1R allele in cardiomyocytes (IGFR+/−IR−/−). Intravenous administration of IGF-1 or 75 hours of swimming over 4 weeks increased IGF1R tyrosine phosphorylation in the heart in control and CIRKO mice but not in CIGFRKO mice. Intriguingly, IR tyrosine phosphorylation in the heart was also increased following IGF-1 administration or exercise training in control and CIGFRKO mice but not in CIRKO mice. The extent of cardiac hypertrophy following exercise training in CIGFRKO and CIRKO mice was comparable to that in control mice. In contrast, exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy was significantly attenuated in IGFR−/−IR+/− and IGFR+/−IR−/− mice. Thus, IGF-1 and exercise activates both IGF1R and IR in the heart, and IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals may serve redundant roles in the hypertrophic responses of the heart to exercise training.

Keywords: insulin-like growth factor receptor, insulin receptor, exercise, cardiac hypertrophy, tyrosine phosphorylation

1. Introduction

Postnatal myocardial growth is primarily achieved through hypertrophy of individual myocytes[1]. In addition to normal heart growth during postnatal development, heart size increases in response to various forms of both extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli[2], and these hypertrophic responses are classified either as “pathological” or “physiological”. Pathological cardiac hypertrophy is frequently associated with contractile dysfunction and histological pathology such as interstitial fibrosis, and is typically observed in patients with hypertension, myocardial infarction, and valvular heart diseases. On the other hand, physiological cardiac hypertrophy is characterized by normal or enhanced contractility and normal cardiac architecture, as typically observed in trained athletes[3, 4]. Notably, exercise training is beneficial in a selected population of heart failure patients[5], and reverses molecular and functional abnormalities of the heart in animal models of pathological hypertrophy[6–8]. Thus, promoting physiological cardiac hypertrophy may be one of the therapeutic options for heart diseases.

The insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway has been implicated in the development of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy[9, 10]. Increased cardiac IGF-1 formation is associated with physiological hypertrophy in athletes[11], and exercise training increases IGF-1 mRNA expression in rat hearts[12]. Overexpression of IGF-1 in the heart in transgenic mice induces physiological cardiac hypertrophy in the early phases of postnatal development[13], and IGF-1 receptor (IGF1R) overexpression in the heart results in physiological cardiac hypertrophy associated with activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway[14]. Overexpression of a constitutively-active p110α PI3K results in physiological cardiac hypertrophy[15], and exercise-induced hypertrophy is completely abolished by dominant-negative p110α overexpression[14, 16]. Short-term or moderate levels of Akt1 overexpression in the heart induces physiological cardiac hypertrophy[17, 18], whereas development of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy is blunted in Akt1 knockout mice[19]. These results collectively suggest that IGF-1 or IGF1R is sufficient whereas PI3K-Akt pathway is both necessary and sufficient to induce physiological cardiac hypertrophy. A recent study in mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted deletion of IGF1R suggested that cardiac IGF1R signaling could modulate exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy[20]. In this study, 96 hours of swim training over 5 weeks led to increased AMPK activation in IGF1R deficient hearts, and AMPK activation was postulated to have a negative impact on cardiac hypertrophy. Insulin receptor (IR)-mediated signals have also been implicated in the regulation of cardiac growth and function. Cardiac-specific IR knockout (CIRKO) mice exhibit small heart size with mildly impaired contractility and reduced Akt activity[21, 22], suggesting that IR-mediated signals could potentially play a role in exercise-induced physiological hypertrophy.

To elucidate the role of IGF1R and IR in the development of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy, we subjected cardiac-specific IGF1R knockout (CIGFRKO) mice and CIRKO mice to 75 hours of swimming over 4 weeks. Although both CIGFRKO mice and CIRKO mice developed exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy to the level comparable to their wild-type littermates, deletion of a single Ir or a single Igf1r allele on CIGFRKO or CIRKO background, respectively, blunted hypertrophic responses to exercise. We also observed that tyrosine phosphorylation of both IGF1R and IR was increased in the heart after intravenous IGF-1 administration or exercise training. Thus, IGF-1 and exercise may activate both IGF1R and IR in the heart, and IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals may play redundant roles in the development of cardiac hypertrophy in response to exercise training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Exercise Training, and IGF-1 Administration

CIGFRKO mice were initially generated by crossing Igf1rflox/flox mice[23] with α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC)-Cre transgenic mice[24]. Subsequent maintenance of CIGFRKO line was done by crossing CIGFRKO mice (Igf1rflox/floxCre+/−) with Igf1rflox/floxCre−/− mice. CIRKO mice were generated as described previously[21]. Subsequent maintenance of CIRKO line was done by crossing CIRKO mice (Irflox/floxCre+/−) with Irflox/floxCre−/− mice. Cardiac-specific Igf1r−/−Ir+/− mice and Igf1r+/−Ir−/− mice were generated by crossing Igf1rflox/floxIrflox/floxCre−/− mice with CIGFRKO mice (Igf1rflox/floxIr+/+Cre+/−) and CIRKO mice (Igf1r+/+Irflox/floxCre+/−), respectively. Animals were on a mixed background of C57BL/6J, 129Sv, and FVB, and littermates that contain the same combination of Igf1r/Ir alleles but do not contain αMHC-Cre transgene were used as wild type controls in each study (Supplementary Figure S1). Genotyping was performed as described[21, 25].

Swimming training was performed in 10-week-old male mice as described previously[26]. Swimming sessions were done twice a day for 28 days. The first 7 days consisted of a training period in which one session was a 20 min long on the first day and it was increased by 10 min per day. On the subsequent 21 days, two sessions of 90 min swimming were done. After the final swimming session, mice were overnight fasted and sacrificed. M-mode tracings of left ventricular wall motion at the level of papillary muscle were obtained using Vevo 660 Imaging system (Visual Sonic) with a 25-MHz transducer. For IGF-1 or insulin administration, mice were overnight fasted and anesthetized with pentobarbital, and IGF-1 (Fujisawa Co., Japan) or insulin (Lilly Co., Japan) was intravenously administered. Animals were sacrificed 5 minutes after IGF-1 or insulin administration. All animal procedures were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chiba University.

2.2. Histological Analysis

Hearts were fixed and embedded in paraffin for histological analyses. Serial sections of 4 µm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for morphological analysis and Masson’s trichrome (MT) for detection of fibrosis. For measurements of myocyte cross-sectional area, immunohistochemistry with anti-dystrophin antibody (Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK) was performed to visualize myocyte membranes. The sections were reacted with anti-dystrophin antibody at 1:20 and visualized by ABC method. Suitable cross-sections for measurements were defined as having round-to-oval membrane staining using ImageJ software. At least 200 myocytes were measured in each sample.

2.3. Western Blot Analysis and Immunoprecipitation

Total protein lysate was extracted from heart tissue and SDS-PAGE was performed as described previously[22]. Anti-IGF1Rβ, anti-IRβ, and anti-phosphotyrosine (PY20) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-actin antibody was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). For immunoprecipitation, total heart lysates (500 µg protein) were precleared with protein G-agarose beads for an hour before incubation with the indicated antibody (1 µg) overnight at 4 °C. Protein G-agarose beads were added for three hours and immnoprecipitates were washed three times in lysis buffer, eluted in 2 x SDS buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test or Welch’s test. P values of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. CIGFRKO mice exhibit no cardiac phenotype at baseline

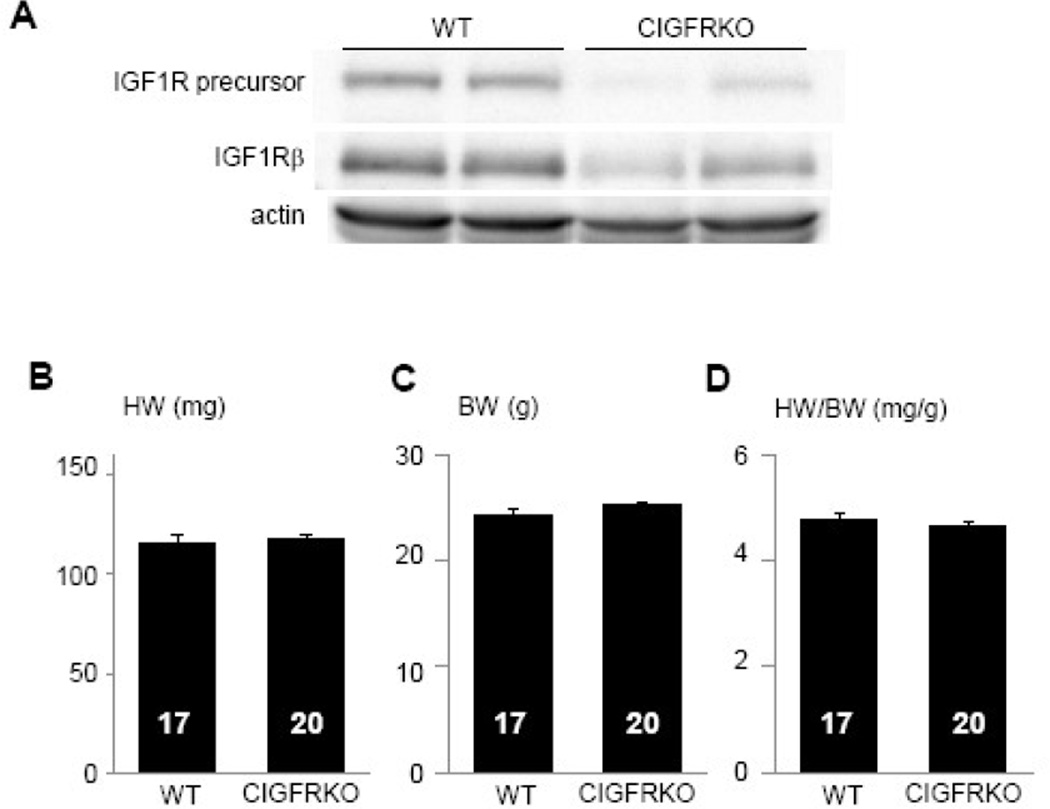

CIGFRKO mice were initially generated by crossing Igf1rflox/flox animals with αMHC-Cre transgenic mice, and compared with wild type controls. Western blot analysis of heart lysate revealed that the expression levels of IGF1R precursor protein and IGF1R β subunit protein were reduced, and small amount of proteins detected by western blots were considered to be derived from non-myocytes in the heart (Figure 1A). At 10 weeks of age, there was no significant difference in heart weight (HW), body weight (BW), heart weight (HW)/BW ratio, and cardiac function as assessed by echocardiography between CIGFRKO mice and wild type (WT) littermates (Figure 1B–1D, and data not shown). Similar results were obtained in other ages. Thus, CIGFRKO mice exhibit no obvious cardiac phenotype at baseline.

Fig. 1. CIGFRKO mice exhibit no obvious cardiac phenotype at baseline.

(A) Expression of IGF1R precursor protein and IGF1R β subunit protein (IGF1Rβ) as revealed by western blot analysis of whole heart lysates. Actin served as internal control. (B–D) HW (B), BW (C), and HW/BW ratio (D) of WT and CIGFRKO mice at 10 weeks of age. The number of mice analyzed is shown in the bar.

3.2. Deletion of Igf1r in cardiac myocytes does not attenuate exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy

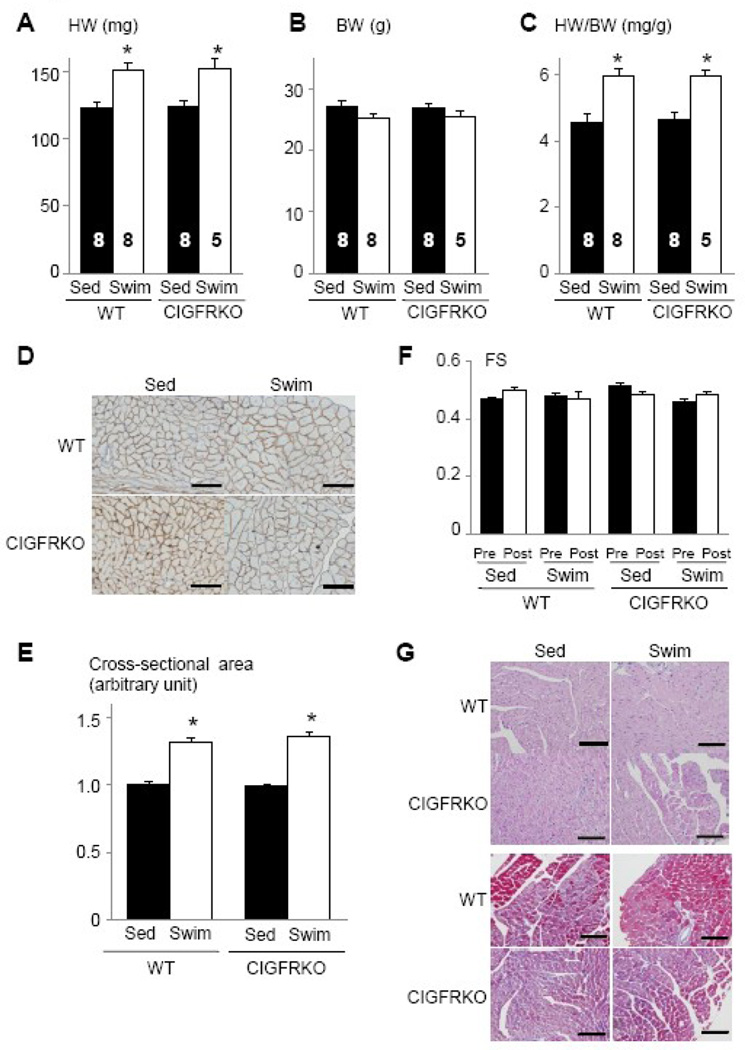

Lack of obvious cardiac phenotype in CIGFRKO mice at baseline prompted us to investigate the effect of Igf1r deletion on hypertrophic responses of the heart to exercise training. After 75 hours of swimming over 4 weeks, WT and CIGFRKO mice developed similar degrees of cardiac hypertrophy as measured by HW and HW/BW ratio (Figure 2A–2C). The fold-increase in myocyte cross-sectional area was also comparable between WT and CIGFRKO animals (Figure 2D and 2E). Left ventricular contractile function as measured by echocardiography did not differ between WT and CIGFRKO mice (Figure 2F), and histological analyses revealed that there was no interstitial fibrosis or myocyte disarray in the hearts of WT and CIGFRKO mice (Figure 2G). The presence of Cre recombinase in the heart did not affect the extent of hypertrophy or contractile function following exercise training (Supplementary Figure S2). These results collectively suggest that exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy may develop normally in the absence of IGF1R-mediated signals in cardiac myocytes.

Fig. 2. CIGFRKO mice develop physiological cardiac hypertrophy in response to exercise training.

(A–C) HW (A), BW (B), and HW/BW ratio (C) of WT and CIGFRKO mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype. The number of mice analyzed is shown in the bar. (D) Immunohistochemistry with anti-dystrophin antibody. Scale bar=50µm. (E) Myocyte cross-sectional area of WT and CIGFRKO mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype. (F) Left ventricular contractile function as assessed by echocardiographic measurement of fractional shortening (FS). Pre and Post represent before and after exercise, respectively. (G) Histological analysis with HE (upper panel) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) (lower panel) staining. Scale bar=100µm. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively.

3.3. IR is phosphorylated by IGF-I in the hearts of WT and CIGFRKO mice

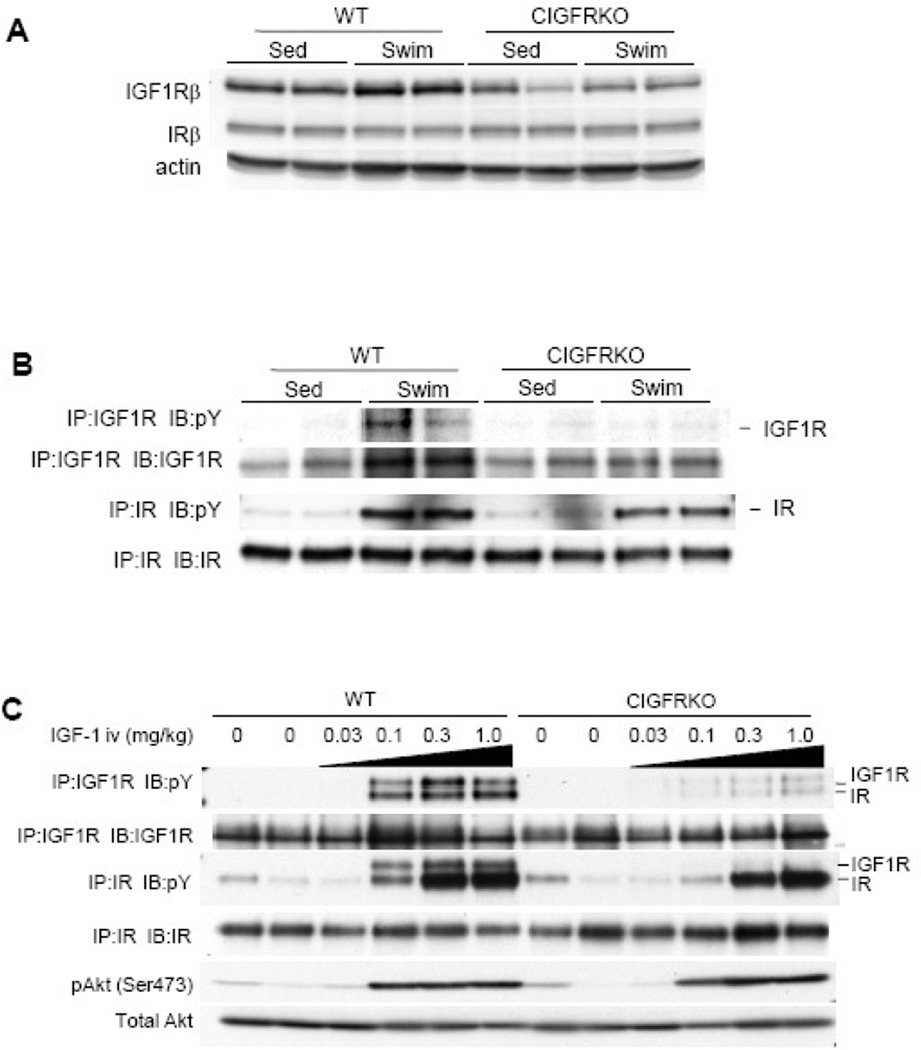

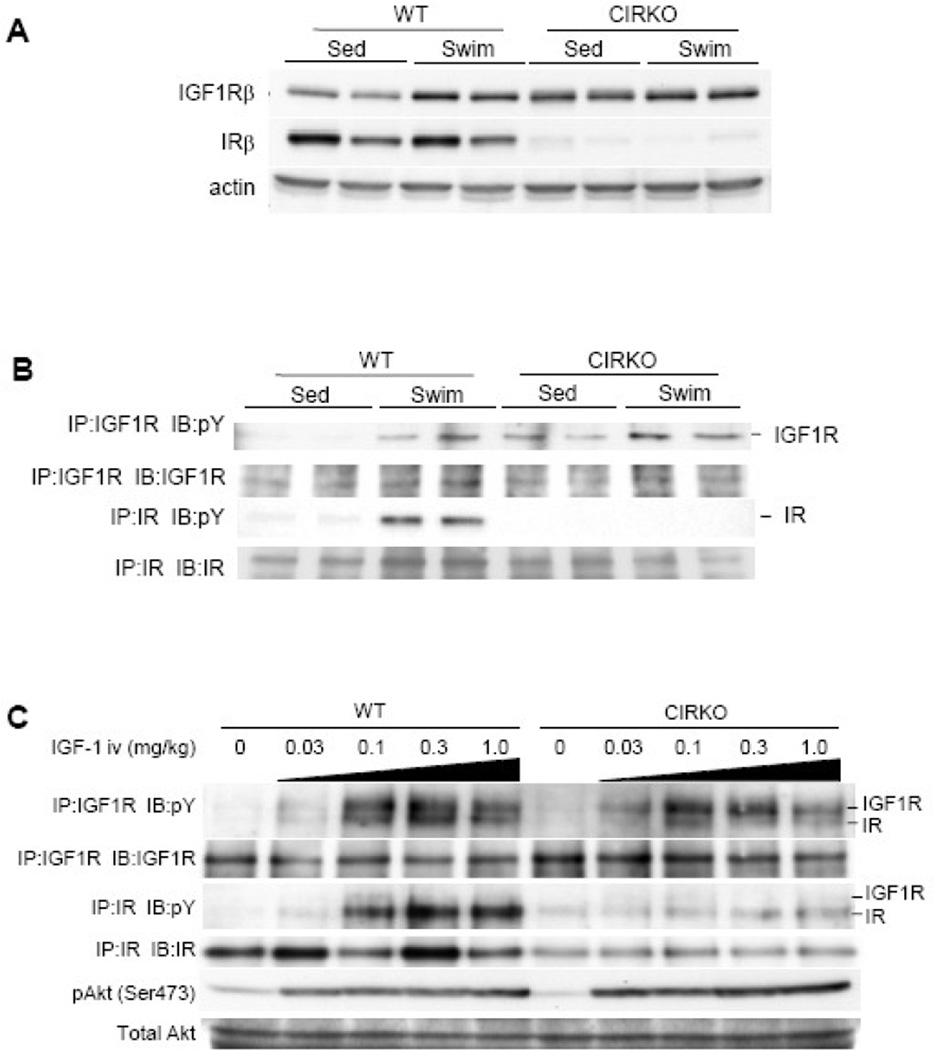

Since IGF-1 signaling has been implicated in the development of physiological cardiac hypertrophy, the above-mentioned results were somewhat unexpected. We first examined whether IGF1R-mediated signals were disrupted in cardiac myocytes of CIGFRKO mice. Western blot analysis of whole heart extracts revealed that, although IGF1R protein levels were upregulated after exercise training in the hearts of WT mice, the expression levels of IGF1R remained at low levels both in sedentary and swim-trained CIGFRKO hearts (Figure 3A). Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R and IR were also examined in the heart of WT and CIGFRKO mice after exercise training. Exercise training icreased phosphorylation levels of both IGF1R and IR in the heart of WT mice. Increased phosphorylation levels of IGF1R could be in part attributed to upregulation of IGF1R protein levels following exercise training. As expected, IGF1R phosphorylation but not IR phosphorylation was blunted in the heart of CIGFRKO animals (Figure 3B). IGF1R tyrosine phosphorylation levels were also examined in the hearts of WT and CIGFRKO mice after intravenous IGF-1 administration. Phospho-tyrosine blot after IGF1R immunoprecipitation revealed that tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF1R was markedly reduced in CIGFRKO hearts when compared to that of WT hearts (Figure 3C, upper panel). These findings strongly suggest that IGF1R-mediated signaling is functionally disrupted in cardiac myocytes of CIGFRKO animals. In the same experimental condition, phospho-tyrosine blot after IR immunoprecipitation revealed significant tyrosine phosphorylation of IR both in WT and CIGFRKO hearts after IGF-1 administration (Figure 3C, middle panel), and phospho-Akt levels in the heart were comparable between WT and CIGFRKO animals (Figure 3C, lower panel). These observations collectively suggest that IR activated by IGF-1 in part mediates exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy and that IR compensates for the loss of IGF1R-mediated signaling in the hearts of CIGFRKO mice following exercise training.

Fig. 3. Western Blot analysis of CIGFRKO heart extracts after exercise or IGF-I administration.

(A) Expression of IGF1R β subunit protein (IGF1Rβ) and IR β subunit protein (IRβ) in the heart of WT and CIGFRKO mice. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively. (B) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R and IR following exercise training. pY represents anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. IP and IB represent immunoprecipitation and immunoblot, respectively. (C) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R/IR and activation of Akt in the heart of WT and CIGFRKO mice 5 minutes after IGF-1 administration. There are some IGF1R bands in the immunoprecipitates of IR and vice versa, possibly due to antibody cross-reactivity. pY represents anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. IP and IB represent immunoprecipitation and immunoblot, respectively.

3.4. Deletion of Ir in cardiac myocytes does not attenuate exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy

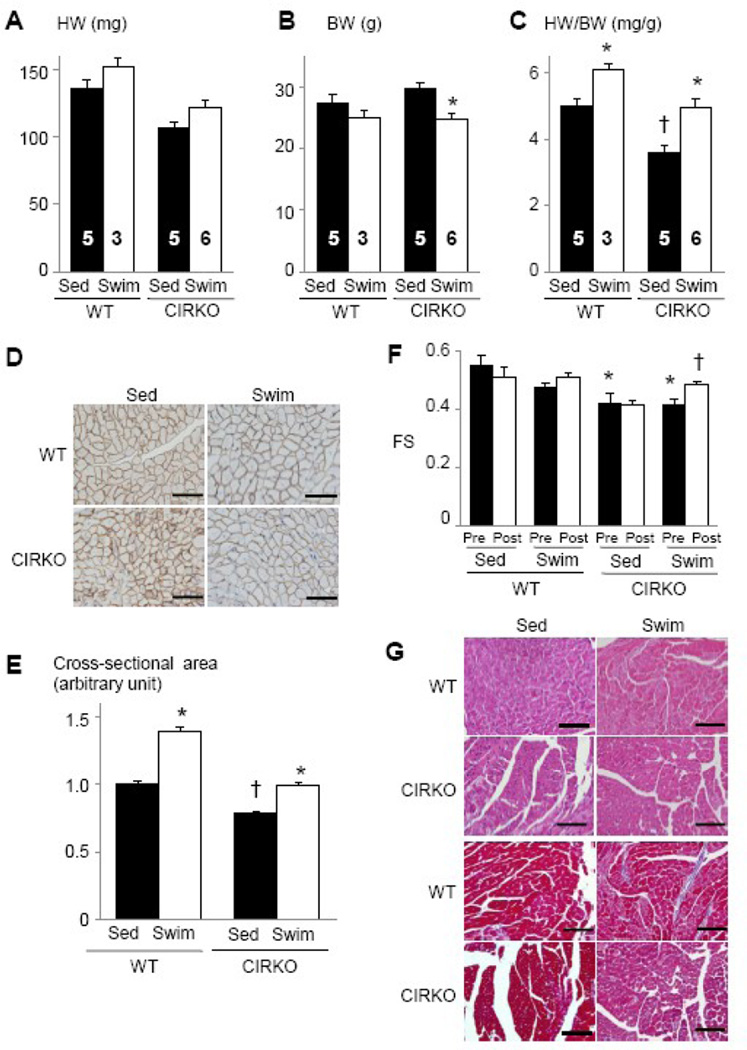

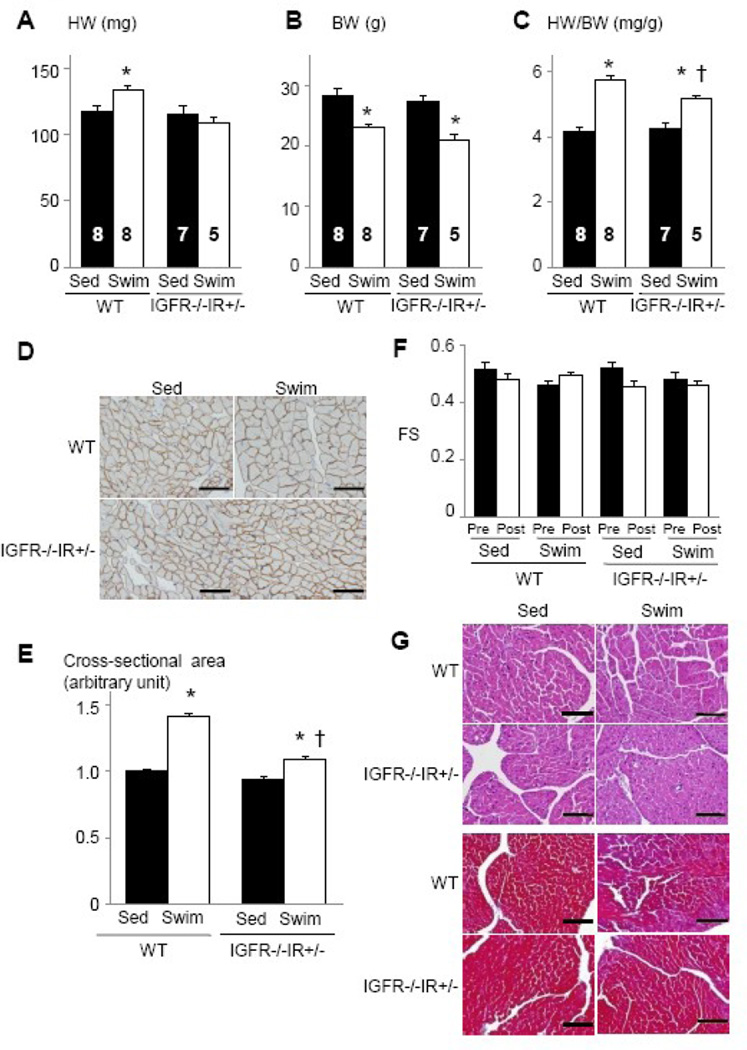

To test the hypothesis that IR mediates exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy, CIRKO mice and wild type littermates were subjected to exercise training. After 75 hours of swimming, WT and CIRKO mice exhibited similar degrees of cardiac hypertrophy as measured by HW (12% versus 14%) and HW/BW ratio (22% versus 38%) (Figure 4A–4C). The fold-increase in myocyte cross-sectional area was also significant in WT and CIGFRKO animals (40% and 27%, respectively) (Figure 4D and 4E). The relatively enhanced response in HW/BW ratio following exercise was considered to be due to a significant decrease in BW in CIRKO mice following exercise training (Figure 4B). Interestingly, left ventricular contractile function as assessed by fractional shortening was slightly impaired in CIRKO mice, which was ameliorated by exercise training (Figure 4F). There was no sign of pathology in histological examination both in WT or CIRKO hearts (Figure 4G). Thus, exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy develops normally even in the absence of IR-mediated signals in cardiac myocytes.

Fig. 4. CIRKO mice develop physiological cardiac hypertrophy in response to exercise training.

(A–C) HW (A), BW (B), and HW/BW ratio (C) of WT and CIRKO mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype, †p < 0.05 versus WT Sed group. The number of mice analyzed is shown in the bar. (D) Immunohistochemistry with anti-dystrophin antibody. Scale bar=50µm. (E) Myocyte cross-sectional area of WT and CIRKO mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype. †p < 0.05 versus WT Sed group. (F) Left ventricular contractile function as assessed by echocardiographic measurement of fractional shortening (FS). Pre and Post represent before and after exercise, respectively. *p < 0.05 versus WT Sed Pre group, †p < 0.05 versus CIRKO Swim Pre group. (G) Histological analysis with HE (upper panel) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) (lower panel) staining. Scale bar=100µm. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively.

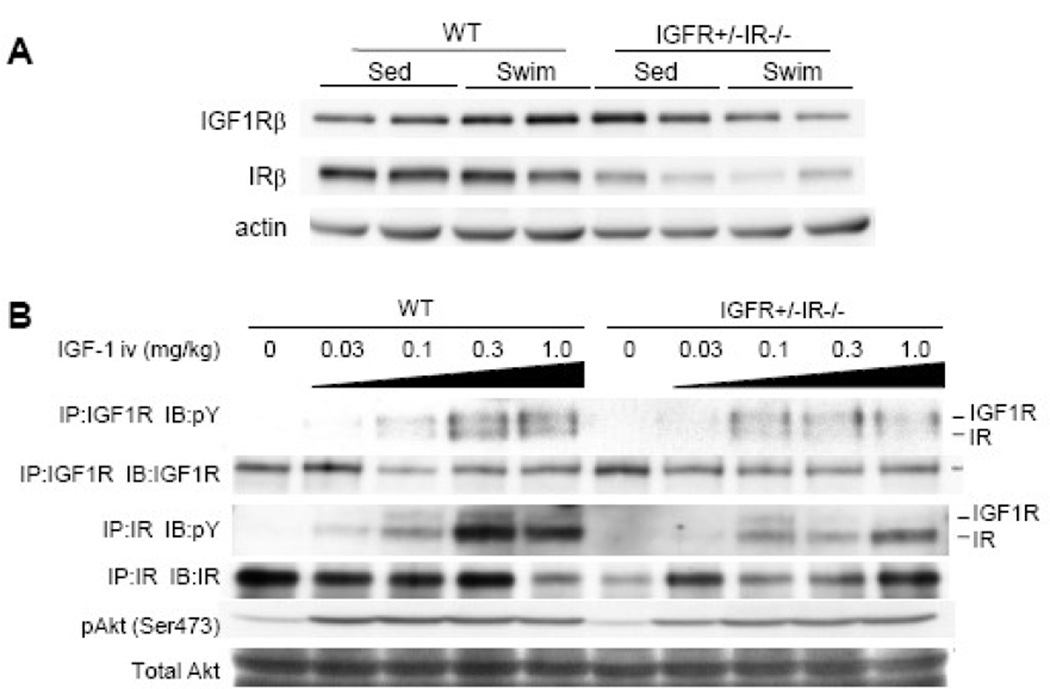

Western blot analysis of whole heart extracts revealed that the expression levels of IGF1R were increased in CIRKO hearts at the sedentary state compared to those of WT hearts, and further upregulated after exercise both in WT and CIRKO hearts (Figure 5A). Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R were upregulated both in WT and CIRKO hearts after exercise training, whereas those of IR were upregulated in WT hearts but not in CIRKO hearts (Figure 5B). When IGF-1 was intravenously administered, phospho-tyrosine blot after IGF1R immunoprecipitation revealed that tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF1R was comparable between CIRKO hearts and WT hearts (Figure 5C, upper panel), whereas phospho-tyrosine blot after IR immunoprecipitation revealed that IR tyrosine phosphorylation by IGF-I was markedly reduced in CIRKO hearts (Figure 5C, middle panel). Phospho-Akt levels in the heart were comparable between WT and CIRKO animals (Figure 5C, lower panel). These observations indicate that IR-mediated signals are dispensable for the development of exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy.

Fig. 5. Western Blot analysis of CIRKO heart extracts after exercise or IGF-1 administration.

(A) Expression of IGF1R β subunit protein (IGF1Rβ) and IR β subunit protein (IRβ) in the heart of WT and CIRKO mice. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively. (B) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R an IR following exercise training. pY represents anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. IP and IB represent immunoprecipitation and immunoblot, respectively. (C) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R/IR and activation of Akt in the heart of WT and CIRKO mice 5 minutes after IGF-1 administration. There are some IGF1R bands in the immunoprecipitates of IR and vice versa, possibly due to antibody cross-reactivity. pY represents anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. IP and IB represent immunoprecipitation and immunoblot, respectively.

3.5. Combined deletion of Igf1r and Ir attenuates exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy

The observation that the deletion of either Igf1r alone or Ir alone in cardiac myocytes does not attenuate swimming-induced cardiac hypertrophy suggests that IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals could compensate for each other during the development of exercise-induced physiological cardiac growth. To test this hypothesis, we generated compound mutants of Igf1r and Ir genes in the heart. Homozygous deletion of both genes in cardiac myocytes resulted in severe heart failure and early postnatal lethality (data not shown), consistent with a previous report in which Igf1r and Ir genes were disrupted in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells[27]. We therefore analyzed mice lacking two Igf1r alleles and one Ir allele (IGF1R−/−IR+/−) or mice lacking one Igf1r allele and two Ir alleles (IGF1R+/−IR−/−) in cardiac myocytes.

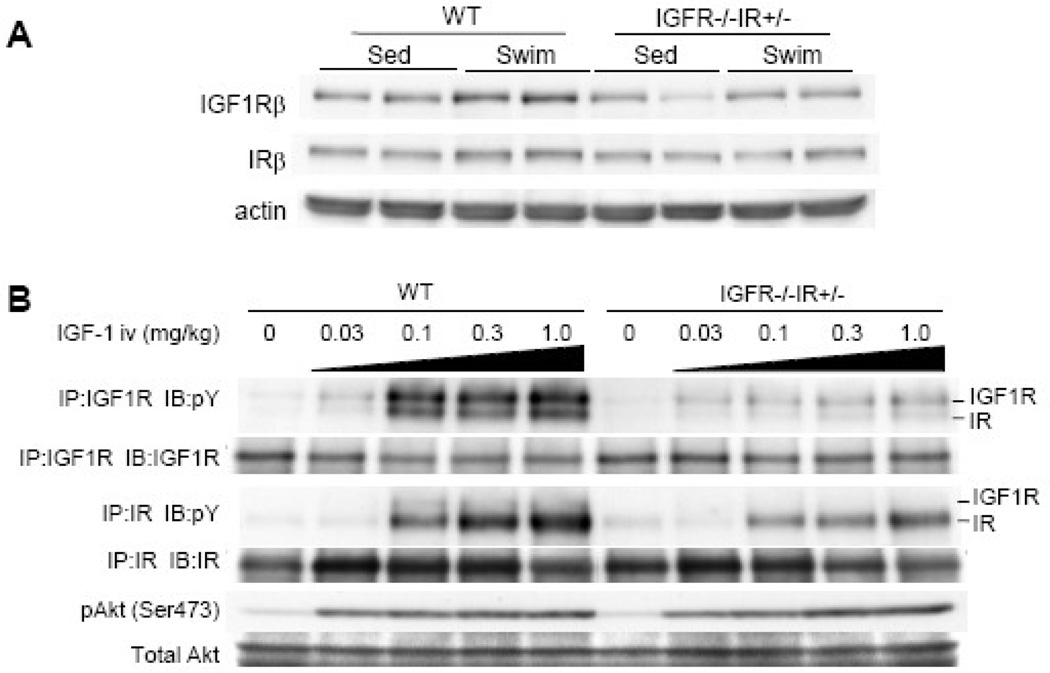

At sedentary state, HW and HW/BW ratio of IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice was comparable to that of WT mice. When these animals were subjected to 75 hours of swimming, the increase in HW and HW/BW ratio was significantly reduced in IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice compared to WT mice (Figure 6A–6C). The increase in myocyte cross-sectional area was also significantly reduced in IGF1R−/−IR+/− animals compared to WT littermates (Figure 6D and 6E). Left ventricular contractile function was not affected by gene deletion and/or exercise training (Figure 6F), and there was no pathological finding on histology (Figure 6G). Western blot analysis of whole heart extracts revealed that the expression levels of IR were slightly reduced in IGF1R−/−IR+/− hearts and were not altered by exercise (Figure 7A). When IGF-1 was intravenously administered, tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF1R was markedly reduced (Figure 7B, upper panel), and that of IR was also moderately reduced (Figure 7B, middle panel). Phospho-Akt levels in the heart were comparable between WT and IGF1R−/−IR+/− animals (Figure 7B, lower panel).

Fig. 6. Exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy is attenuated in IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice.

(A–C) HW (A), BW (B), and HW/BW ratio (C) of WT and IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype, †p < 0.05 versus WT Swim group. The number of mice analyzed is shown in the bar. (D) Immunohistochemistry with anti-dystrophin antibody. Scale bar=50µm. (E) Myocyte cross-sectional area of WT and IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype. †p < 0.05 versus WT Swim group. (F) Left ventricular contractile function as assessed by echocardiographic measurement of fractional shortening (FS). Pre and Post represent before and after exercise, respectively. (G) Histological analysis with HE (upper panel) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) (lower panel) staining. Scale bar=100µm. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively.

Fig. 7. Western Blot analysis of IGF1R−/−IR+/− heart extracts after exercise or IGF-1 administration.

(A) Expression of IGF1R β subunit protein (IGF1Rβ) and IR β subunit protein (IRβ) in the heart of WT and IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively. (B) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R/IR and activation of Akt in the heart of WT and IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice 5 minutes after IGF-1 administration. There are some IGF1R bands in the immunoprecipitates of IR and vice versa, possibly due to antibody cross-reactivity. pY represents anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. IP and IB represent immunoprecipitation and immunoblot, respectively.

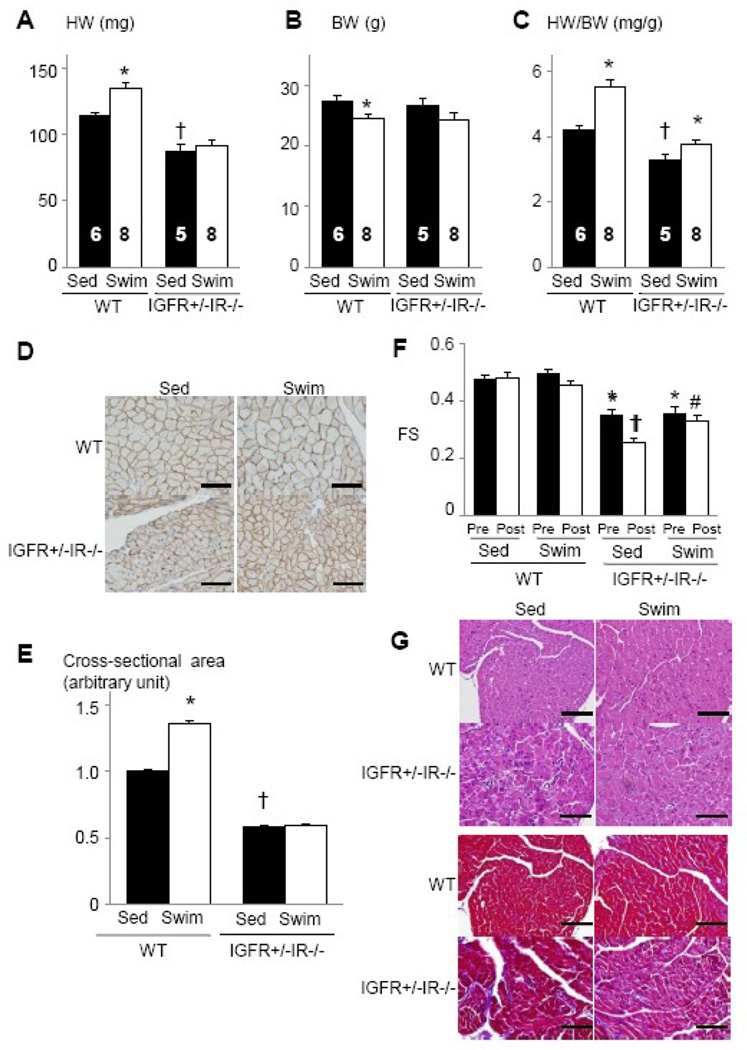

In contrast to IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice, IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice exhibited small heart size at baseline, and the increase in HW and HW/BW ratio after 4 weeks of swimming was significantly reduced in IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice compared to WT mice (Figure 8A–8C). The increase in myocyte cross-sectional area was also markedly reduced in IGF1R+/−IR−/− animals compared to WT littermates (Figure 8D and 8E). Echocardiography revealed a progressive decline in left ventricular contractile function in IGF1R+/−IR−/−mice, which was in part ameliorated by exercise training (Figure 8F). Histological analysis demonstrated interstitial fibrosis in the heart of IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice at sedentary state, which was markedly reduced by exercise training (Figure 8G). Western blot analysis of whole heart extracts revealed that the expression levels of IGF1R were upregulated in IGF1R+/−IR−/− hearts at sedentary state but there was no further upregulation of IGF1R expression after swimming (Figure 9A). When IGF-1 was intravenously administered, tyrosine phosphorylation of IGF1R was moderately reduced (Figure 9B, upper panel), and that of IR was markedly reduced (Figure 9B, middle panel). Phospho-Akt levels in the heart were also reduced in the heart of IGF1R+/−IR−/−animals compared to WT mice (Figure 9B, lower panel). These observations indicate that IR expressed from a single Ir allele is sufficient to maintain normal postnatal cardiac growth but is insufficient to support the full program of hypertrophic responses to exercise training, whereas IGF1R derived from a single Igf1r allele is insufficient both for the maintenance of postnatal cardiac growth/function and for the development of exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy.

Fig. 8. Exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy is attenuated in IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice.

(A–C) HW (A), BW (B), and HW/BW ratio (C) of WT and IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice. *p < 0.05 versus Sed group of the same genotype, †p < 0.05 versus WT Sed group. The number of mice analyzed is shown in the bar. (D) Immunohistochemistry with anti-dystrophin antibody. Scale bar=50µm. (E) Myocyte cross-sectional area of WT and IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice. *p < 0.05 versus WT Sed group. †p < 0.05 versus WT Sed group. (F) Left ventricular contractile function as assessed by echocardiographic measurement of fractional shortening (FS). Pre and Post represent before and after exercise, respectively. *p < 0.05 versus WT Sed Pre group, †p < 0.05 versus IGF1R+/−IR−/− Sed Pre group, #p < 0.05 versus IGF1R+/−IR−/− Sed Post group. (G) Histological analysis with HE (upper panel) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) (lower panel) staining. Scale bar=100µm. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively.

Fig. 9. Western Blot analysis of IGF1R+/−IR−/− heart extracts after exercise or IGF-1 administration.

(A) Expression of IGF1R β subunit protein (IGF1Rβ) and IR β subunit protein (IRβ) in the heart of WT and IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice. Sed and Swim represent a sedentary and a swimming group, respectively. (B) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of IGF1R/IR and activation of Akt in the heart of WT and IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice 5 minutes after IGF-1 administration. There are some IGF1R bands in the immunoprecipitates of IR and vice versa, possibly due to antibody cross-reactivity. pY represents anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. IP and IB represent immunoprecipitation and immunoblot, respectively.

4. Discussion

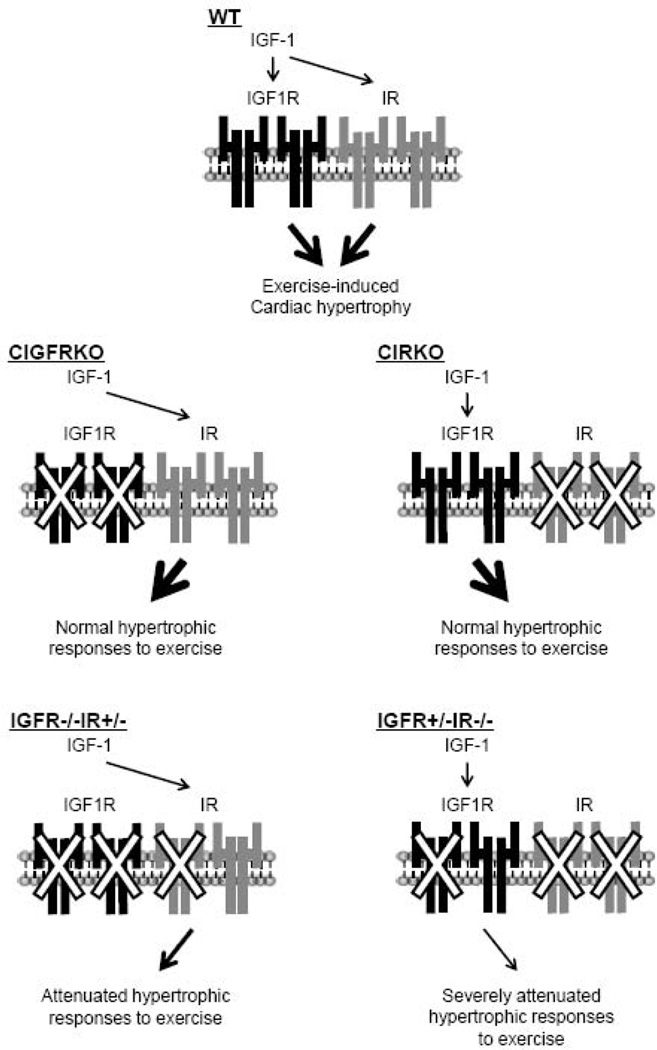

In the present study we have dissected the roles of IGF1R and IR in normal postnatal cardiac growth and exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. We found that IGF1R and IR have overlapping or redundant functions in these two processes of physiological cardiac growth. We also found that both IGF1R and IR are activated by IGF-1 or exercise, implying that IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals could contribute to hypertrophic responses of the heart to exercise training. These results suggest the existence of a complex signaling network involving IGF1R, IR, and their ligands in the regulation and maintenance of cardiac growth and function (Figure 10).

Fig. 10. Schematic illustration of the interaction and crosstalk between IGF1R-and IR-mediated signals in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

IGF-1 activates both IGF1R and IR in the heart in response to exercise training. Exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy develops normally in CIGFRKO mice and CIRKO mice, although combined deletion of two Igf1r alleles and one Ir allele or one Igf1r allele and two Ir alleles results in the attenuation of exercise-induced hypertrophy. Thus, exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy is mediated both by IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals in a redundant fashion. IGF-1 appears to be a major factor that activates both IGF1R and IR. The contribution of insulin in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy is not clear from our present study.

Biological actions of insulin and IGF-1 are transduced by IR and IGF1R. These receptors are highly homologous and exist as α2β2 heterodimers, with two extracellular ligand-binding α subunits and two transmembrane b subunits that contain tyrosine kinase domains[28]. There also exists a hybrid IR-IGF1R receptor formed by IR α-β heterodimer and IGF1R α-β heterodimer, which preferentially binds to IGF-1 but not to insulin[29]. Under normal conditions, insulin and IGF-1 signal primarily through their cognate receptors. Thus, insulin signaling acutely regulates glucose metabolism whereas IGF-1 signaling regulates embryonic and postnatal body/organ size. This notion is supported by distinct phenotypes of IR and IGF1R knockout mice: IR deficient mice are perinatally lethal due to severe ketoacidosis whereas IGF1R deficient mice exhibit severe growth retardation (~45% of normal size)[30]. However, it is probably an oversimplification to view that IR mediates metabolic actions and IGF1R mediates growth. Indeed, IR deficient mice are slightly smaller than wild type mice (~90% of normal size), and combined deletion of IR and IGF1R results in more severe growth retardation (~30% of normal size) than IGF1R single deletion[30]. Thus, IR and IGF1R have functional redundancies in mediating growth promoting effects during embryonic development.

We previously reported that CIRKO mice exhibit a small heart phenotype (~80% of the wild type heart size). Based on the observation that IGF1R deficient mice show more severe growth retardation than IR deficient mice[30], we initially hypothesized that IGF1R-mediated signals would play a dominant role over IR-mediated signals in normal postnatal cardiac growth. However, we found that there was no obvious cardiac phenotype in CIGFRKO mice at baseline. Furthermore, simultaneous deletion of Ir and Igf1r in cardiac myocytes resulted in perinatal lethality with contractile dysfunction and reduced heart size (data not shown). These observations suggest that IR and IGF1R have functional redundancies in mediating postnatal cardiac growth and that IR plays a dominant role over IGF1R in this process. Although the basis for differential contribution of IR and IGF1R to embryonic development (IR < IGF1R) versus postnatal heart growth (IR > IGF1R) is not clear, it may be due to differences in relative expression levels of IR, IGF1R, and their ligands during embryonic versus postnatal development.

The lack of obvious cardiac phenotype in CIGFRKO mice prompted us to investigate the effect of Igf1r deletion in the heart under stressed conditions. Previous studies implicated a critical role of IGF-1-PI3K-Akt pathway in the development of exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy[9, 10]. Specifically, gain-of-function studies in transgenic mice revealed that IGF1R is capable of inducing physiological cardiac growth[14]. We therefore hypothesized that hypertrophic responses to exercise training might be impaired in the heart of CIGFRKO mice. Unexpectedly, however, both wild type and CIGFRKO mice developed comparable levels of cardiac hypertrophy in response to swimming training. In addition, IGF-1 administration or exercise training induced extensive tyrosine phosphorylation of IR in the heart of wild type and CIGFRKO mice. On the contrary, insulin administration induced robust phosphorylation of IR but not IGF1R (Supplementary Figure S3). These findings suggest that both IGF1R and IR can be activated by IGF-1 and may contribute to the development of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy in a functionally redundant fashion. This notion was further supported by our studies in CIRKO, IGF1R−/−IR+/−, and IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice, in which combined deletion of Igf1r and Ir gene in cardiac myocytes attenuated hypertrophic responses of the heart to exercise training whereas deletion of Ir gene alone did not. Furthermore, the observation that IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice were more severely impaired in hypertrophic responses to exercise than IGF1R−/−IR+/−mice suggests that IR-mediated signals might play a dominant role over those mediated by IGF1R in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy, as is the case with normal postnatal cardiac growth. Our results also suggest the possibility that the small heart phenotype of CIRKO mice is in part due to the impairment of IR signals activated by IGF-1 or IGF-2 but not by insulin.

The IGF-1-PI3K-Akt pathway has been implicated in physiological cardiac growth. However, the precise mechanism by which this signaling pathway regulates cardiac growth is not completely understood. Although IR appears to be activated by IGF-1 in the heart, the binding affinity of IGF-1 to IR has been reported to be ~100-fold lower relative to that of insulin to IR. One possible mechanism of crosstalk between IGF-1 and IR is the ability of IGF1R-IR hybrid receptors to bind to IGF-1 but not to insulin. It was also recently shown that IGF-1 activate IR at physiological concentrations in murine fibroblasts[31]. In this case, IGF-1 selectively activates IRS-2 and the PI3K pathway but not the IRS-1 and ERK pathway. These and other potential mechanisms of IR activation by IGF-1 could contribute to the development of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

Kim et al recently reported that exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy is attenuated in CIGFRKO mice and that activation of AMPK in the heart of CIGFRKO mice is a potential mechanism leading to impaired hypertrophic responses in these animals[20]. However, we could not detect significant differences in cardiac AMPK activity between WT and CIGFRKO mice either before or after exercise. An important difference between Kim’s study and our own is that the study of Kim et al used a more protracted exercise protocol (96 hours total over 5-weeks) at a higher altitude (4,000 feet above sea level). This might be the reason for the activation of AMPK in CIGFRKO mice in those studies but not in ours. In addition, Kim et al reported that Akt activity was not altered between CIGFRKO mice and wild type mice after exercise training, although the degree of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy was significantly reduced in CIGFRKO animals[20]. In the present study, although exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy was impaired in IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice, phospho-Akt levels of IGF1R−/−IR+/− mice were comparable to wild type mice (Figure 7B). Likewise, although exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy was severely impaired in IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice, phospho-Akt levels in the heart were only slightly impaired in IGF1R+/−IR−/− mice compared to those in wild type mice (Figure 9B). Thus, the level of activation of Akt does not necessarily correlate with the degree of cardiac hypertrophy in Igf1r and Igf1r/Ir compound mutant mice. Taken together, these two studies would suggest that deficiency of IGF-1 signaling in the heart does not prevent exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy on the basis of reduced signaling via the IGF1R to Akt, but may impact cardiac hypertrophy by indirect mechanisms. Our data would suggest that these mechanisms become amplified when insulin and IGF-1 signaling are simultaneously impaired.

In summary, we have demonstrated overlapping roles of IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals in the development of exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 10). The crosstalk between IGF1R- and IR-mediated signals might in part at the level of ligand-receptor interaction at the cell surface upstream of PI3K. Further elucidation of the signaling pathways downstream of the insulin and IGF-1 receptors that modulate physiological cardiac hypertrophy might identify novel targets that could be exploited in the management of heart failure, where evidence exists that function and prognosis might be increased by exercise.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Fujita, R. Kobayashi, and Y. Ishiyama for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to IK, and NIH grant RO1HL070070 to EDA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pasumarthi KB, Field LJ. Cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulation. Circ Res. 2002;90:1044–1054. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020201.44772.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson EN, Schneider MD. Sizing up the heart: development redux in disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1937–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richey PA, Brown SP. Pathological versus physiological left ventricular hypertrophy: a review. J Sports Sci. 1998;16:129–141. doi: 10.1080/026404198366849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coats AJ. Exercise training for heart failure: coming of age. Circulation. 1999;99:1138–1140. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konhilas JP, Watson PA, Maass A, Boucek DM, Horn T, Stauffer BL, Luckey SW, Rosenberg P, Leinwand LA. Exercise can prevent and reverse the severity of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2006;98:540–548. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205766.97556.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMullen JR, Amirahmadi F, Woodcock EA, Schinke-Braun M, Bouwman RD, Hewitt KA, Mollica JP, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Shioi T, Buerger A, Izumo S, Jay PY, Jennings GL. Protective effects of exercise and phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) signaling in dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:612–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606663104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheuer J, Malhotra A, Hirsch C, Capasso J, Schaible TF. Physiologic cardiac hypertrophy corrects contractile protein abnormalities associated with pathologic hypertrophy in rats. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1300–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI110729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiojima I, Walsh K. Regulation of cardiac growth and coronary angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3347–3365. doi: 10.1101/gad.1492806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorn GW., 2nd The fuzzy logic of physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2007;49:962–970. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.079426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neri Serneri GG, Boddi M, Modesti PA, Cecioni I, Coppo M, Padeletti L, Michelucci A, Colella A, Galanti G. Increased cardiac sympathetic activity and insulinlike growth factor-I formation are associated with physiological hypertrophy in athletes. Circ Res. 2001;89:977–982. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheinowitz M, Kessler-Icekson G, Freimann S, Zimmermann R, Schaper W, Golomb E, Savion N, Eldar M. Short- and long-term swimming exercise training increases myocardial insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2003;13:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(02)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delaughter MC, Taffet GE, Fiorotto ML, Entman ML, Schwartz RJ. Local insulinlike growth factor I expression induces physiologic, then pathologic, cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Faseb J. 1999;13:1923–1929. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Huang WY, Zhang L, Tarnavski O, Bisping E, Schinke M, Kong S, Sherwood MC, Brown J, Riggi L, Kang PM, Izumo S. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor induces physiological heart growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4782–4793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shioi T, Kang PM, Douglas PS, Hampe J, Yballe CM, Lawitts J, Cantley LC, Izumo S. The conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway determines heart size in mice. Embo J. 2000;19:2537–2548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Zhang L, Tarnavski O, Sherwood MC, Kang PM, Izumo S. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) plays a critical role for the induction of physiological, but not pathological, cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12355–12360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934654100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Condorelli G, Drusco A, Stassi G, Bellacosa A, Roncarati R, Iaccarino G, Russo MA, Gu Y, Dalton N, Chung C, Latronico MV, Napoli C, Sadoshima J, Croce CM, Ross J., Jr Akt induces enhanced myocardial contractility and cell size in vivo in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12333–12338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172376399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiojima I, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Schiekofer S, Ito M, Liao R, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Disruption of coordinated cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis contributes to the transition to heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2108–2118. doi: 10.1172/JCI24682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeBosch B, Treskov I, Lupu TS, Weinheimer C, Kovacs A, Courtois M, Muslin AJ. Akt1 is required for physiological cardiac growth. Circulation. 2006;113:2097–2104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Wende AR, Sena S, Theobald HA, Soto J, Sloan C, Wayment BE, Litwin SE, Holzenberger M, Leroith D, Abel ED. IGF-1 receptor signaling is required for exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2531–2543. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belke DD, Betuing S, Tuttle MJ, Graveleau C, Young ME, Pham M, Zhang D, Cooksey RC, McClain DA, Litwin SE, Taegtmeyer H, Severson D, Kahn CR, Abel ED. Insulin signaling coordinately regulates cardiac size, metabolism, and contractile protein isoform expression. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:629–639. doi: 10.1172/JCI13946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiojima I, Yefremashvili M, Luo Z, Kureishi Y, Takahashi A, Tao J, Rosenzweig A, Kahn CR, Abel ED, Walsh K. Akt signaling mediates postnatal heart growth in response to insulin and nutritional status. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37670–37677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holzenberger M, Leneuve P, Hamard G, Ducos B, Perin L, Binoux M, Le Bouc Y. A targeted partial invalidation of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene in mice causes a postnatal growth deficit. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2557–2566. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.7.7550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abel ED, Kaulbach HC, Tian R, Hopkins JC, Duffy J, Doetschman T, Minnemann T, Boers ME, Hadro E, Oberste-Berghaus C, Quist W, Lowell BB, Ingwall JS, Kahn BB. Cardiac hypertrophy with preserved contractile function after selective deletion of GLUT4 from the heart. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1703–1714. doi: 10.1172/JCI7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leneuve P, Zaoui R, Monget P, Le Bouc Y, Holzenberger M. Genotyping of Cre-lox mice and detection of tissue-specific recombination by multiplex PCR. Biotechniques. 2001;31:1156–1160. 1162. doi: 10.2144/01315rr05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oka T, Maillet M, Watt AJ, Schwartz RJ, Aronow BJ, Duncan SA, Molkentin JD. Cardiac-specific deletion of Gata4 reveals its requirement for hypertrophy, compensation, and myocyte viability. Circ Res. 2006;98:837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215985.18538.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laustsen PG, Russell SJ, Cui L, Entingh-Pearsall A, Holzenberger M, Liao R, Kahn CR. Essential role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling in cardiac development and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1649–1664. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01110-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slaaby R, Schaffer L, Lautrup-Larsen I, Andersen AS, Shaw AC, Mathiasen IS, Brandt J. Hybrid receptors formed by insulin receptor (IR) and insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) have low insulin and high IGF-1 affinity irrespective of the IR splice variant. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25869–25874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rother KI, Accili D. Role of insulin receptors and IGF receptors in growth and development. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:558–561. doi: 10.1007/s004670000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denley A, Carroll JM, Brierley GV, Cosgrove L, Wallace J, Forbes B, Roberts CT., Jr Differential activation of insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 by insulin-like growth factor-activated insulin receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3569–3577. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01447-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.