ABSTRACT

Proteins forming the tegument layers of herpesviral virions mediate many essential processes in the viral replication cycle, yet few have been characterized in detail. UL21 is one such multifunctional tegument protein and is conserved among alphaherpesviruses. While UL21 has been implicated in many processes in viral replication, ranging from nuclear egress to virion morphogenesis to cell-cell spread, its precise roles remain unclear. Here we report the 2.7-Å crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) UL21 (UL21C), which has a unique α-helical fold resembling a dragonfly. Analysis of evolutionary conservation patterns and surface electrostatics pinpointed four regions of potential functional importance on the surface of UL21C to be pursued by mutagenesis. In combination with the previously determined structure of the N-terminal domain of UL21, the structure of UL21C provides a 3-dimensional framework for targeted exploration of the multiple roles of UL21 in the replication and pathogenesis of alphaherpesviruses. Additionally, we describe an unanticipated ability of UL21 to bind RNA, which may hint at a yet unexplored function.

IMPORTANCE Due to the limited genomic coding capacity of viruses, viral proteins are often multifunctional, which makes them attractive antiviral targets. Such multifunctionality, however, complicates their study, which often involves constructing and characterizing null mutant viruses. Systematic exploration of these multifunctional proteins requires detailed road maps in the form of 3-dimensional structures. In this work, we determined the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of UL21, a multifunctional tegument protein that is conserved among alphaherpesviruses. Structural analysis pinpointed surface areas of potential functional importance that provide a starting point for mutagenesis. In addition, the unexpected RNA-binding ability of UL21 may expand its functional repertoire. The structure of UL21C and the observation of its RNA-binding ability are the latest additions to the navigational chart that can guide the exploration of the multiple functions of UL21.

INTRODUCTION

Due to the limited genomic coding capacity of viruses, viral proteins are often multifunctional. Although herpesviruses have relatively large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes, they encode a number of proteins that mediate more than one unrelated function. A notable example is proteins located within the tegument, a thick protein layer located between the nucleocapsid and the envelope of a herpesviral virion. Although tegument proteins play structural roles, many have additional functions unrelated to viral assembly. For example, while UL36 (1, 2) and UL37 (3, 4) are required for proper viral assembly, both proteins are also necessary for efficient capsid trafficking (5–7), and UL36 additionally harbors deubiquitinating activity in its N terminus (8). UL48 serves as a hub of tegumentation and is necessary for herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) morphogenesis (9–11); it is also known as VP16, or α trans-inducing factor (α-TIF), which nucleates a transcriptional complex to induce the transcription of immediate early viral genes (12–14). Finally, some tegument proteins can bind RNA. For example, UL47 (VP13/14), one of the most abundant components of the tegument in alphaherpesviruses (15), is also a nucleocytoplasmic shuttle (16, 17) that preferentially binds single-stranded polyadenylated RNAs (18), including some viral mRNAs, and may help incorporate them into nascent virions (19).

UL21 is a tegument protein that is conserved among the members of the alphaherpesvirus subfamily (20, 21), with sequence identity ranging from 27 to 84% and sequence similarity ranging from 57 to 94%. Beta- and gammaherpesviruses encode positional homologs of UL21 within their genomes (e.g., human cytomegalovirus [HCMV] UL87 and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus [KSHV] ORF24), but in the absence of obvious sequence similarity, it is not clear whether these proteins share functions. UL21 is required for efficient viral replication, although the extent of this dependency is debated. In HSV-1 and HSV-2, a lack of UL21 results in delay in the production of viral mRNA, viral proteins, and virions (20, 22, 23). In the absence of UL21, titers of HSV-1 (22) and pseudorabies virus (PRV) (24, 25) are decreased 5- to 10-fold, whereas in HSV-2, UL21 appears essential for replication, since nuclear egress is halted in its absence, and no detectable virus is made unless the multiplicity of infection is greatly increased (20). HSV-1 virions lacking UL21 have reduced amounts of the tegument protein UL16 (26), while PRV virions lacking UL21 incorporate smaller amounts of the tegument proteins UL46 and UL49 and of the viral kinase US3 (27). UL21 can bind capsids (28, 29) and, through its interaction with UL16 (25, 30, 31), membrane-associated UL11 and glycoprotein E (gE) (32). Thus, UL21 may promote secondary envelopment by bridging the capsid and the enveloping membrane (32, 33). In line with this hypothesis, when cells are infected with PRV lacking both UL16 and UL21, secondary envelopment is hindered, and clusters of unenveloped particles are found in the cytoplasm (25). Together, these observations suggest that in addition to being a component of the tegument, UL21 plays a role in viral morphogenesis. Additionally, UL21 has been shown to interact with microtubules and promote their polymerization (28). Finally, replacement of the mutated amino acids in UL21 found in the PRV vaccine strain Bartha with wild-type residues rescues the defect in retrograde transit (34) and restores virulence (35), which may suggest a trafficking role for UL21.

Although these roles imply cytoplasmic localization, the majority of UL21 in both infected and transfected cells localizes to the nucleus (28–30, 32, 36), likely to the nuclear rim (20). Except for the observation that nuclear egress is inhibited for HSV-2 lacking UL21 (20), no potential nuclear roles of UL21 have been investigated. These characteristics suggest that UL21 may have even more distinct functions in the herpesvirus replication cycle than are currently known.

Systematic exploration of the various activities of this multifunctional protein would benefit from a detailed road map in the form of its 3-dimensional structure. Here we report the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of UL21 (UL21C) and map four surface regions of potential functional importance. We also describe the unanticipated ability of UL21 to bind RNA, which may hint at a yet unexplored function. In combination with the previously determined structure of the N-terminal domain of UL21 (UL21N) (21), the novel dragonfly-shaped structure of UL21C enables structure-guided mutagenesis and functional exploration of the multiple roles of UL21 in the replication and pathogenesis of alphaherpesviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and expression constructs.

A plasmid encoding full-length HSV-1 strain 17 UL21 in a pET24a vector was a gift from John W. Wills. Inserts corresponding to various UL21C fragments were constructed by overlap extension PCR (37) from the full-length gene. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. SOE PCR (splicing by overlap extension PCR) products were cleaved by NdeI and HindIII and were subcloned into the NdeI/HindIII-cleaved backbone of the pET24a vector containing UL21. This procedure generated constructs comprising various fragments of UL21C preceded by an N-terminal Strep-tag II (StII) and a Gly-Ser linker (see Fig. 1A). To generate the StII-HRV3C-UL21C(275-535) construct, a human rhinovirus (HRV) 3C (PreScission) protease site was inserted between the affinity tag and UL21C. The following expression constructs were generated: pCM013 [StII-UL21C(237-535)], pCM014 [StII-UL21C(275-535)], pCM015 [StII-UL21C(281-535)], and pCM023 [StII-HRV3C-UL21C(275-535)].

TABLE 1.

PCR primer sequences

| Primer | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CM001 | 5′-CGAAATCATATGTGGAGCCACCCGCAG-3′ | Upstream primer, forward |

| CM003 | 5′-GCGGCCAAGCTTATTACACAGACTGTCC-3′ | Downstream primer, reverse |

| CM004 | 5′-GAAAAAGGTAGCGCCACCGTCAGC-3′ | StII-UL21C(237-535), forward |

| CM005 | 5′-GCTGACGGTGGCGCTACCTTTTTC-3′ | StII-UL21C(237-535), reverse |

| CM006 | 5′-GAAAAAGGTAGCGGCCCCACGCTA-3′ | StII-UL21C(281-535), forward |

| CM007 | 5′-TAGCGTGGGGCCGCTACCTTTTTC-3′ | StII-UL21C(281-535), reverse |

| CM008 | 5′-GAAAAAGGTAGCCAGGATTCCGCC-3′ | StII-UL21C(275-535), forward |

| CM009 | 5′-GGCGGAATCCTGGCTACCTTTTTC-3′ | StII-UL21C(275-535), reverse |

| CM016 | 5′-GAAAAACTAGAGGTTCTGTTCCAAGGCCCCCAGGAT-3′ | StII-HRV3C-UL21C(275-535), forward |

| CM017 | 5′-ATCCTGGGGGCCTTGGAACAGAACCTCTAGTTTTTC-3′ | StII-HRV3C-UL21C(275-535), reverse |

FIG 1.

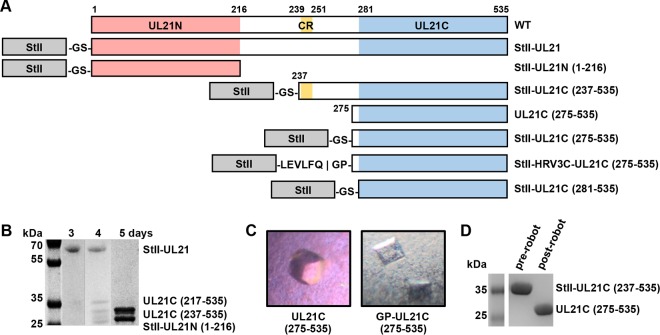

Expression of UL21 constructs. (A) Linear diagrams of the predicted secondary structure and domains of UL21. Amino acid boundaries are indicated. WT, wild type; CR, the conserved region (residues 239 to 251) between UL21N (residues 1 to 216) and UL21C(281-535) that is predicted to form a β-strand. Constructs used in UL21C crystallization trials are also shown. (B) UL21 is proteolytically cleaved during purification by contaminating proteases. (C) UL21C crystals formed by spontaneous cleavage of UL21C during initial screening of crystallization conditions (left) or by cleavage due to an inserted protease cleavage site (right). (D) UL21C was cleaved during initial screening of crystallization conditions.

N-terminal sequencing.

For N-terminal sequencing, protein samples were resolved by 4-to-15% SDS-PAGE and were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was stained with Coomassie blue R-250. The protein bands of interest were cut out and were submitted for sequencing by Edman degradation to the Tufts University Core Facility.

Recombinant protein expression and purification.

All constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta (Novagen) cells using overnight induction at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 to 1.0 with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A [50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)] supplemented with 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1× cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and egg white avidin (Sigma)] and were lysed using either sonication, a French press, or a Microfluidizer. UL21C was captured from the clarified lysate using Strep-Tactin Sepharose resin (GE Healthcare) and was eluted with 5 mM d-desthiobiotin (Sigma) in buffer A.

Prior to crystallization, UL21C was separated from copurifying E. coli nucleic acids (NAs) by use of a HiTrap Heparin Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) in buffer A. UL21C was eluted from heparin in buffer A using a NaCl gradient from 0.1 to 1.0 M. Constructs containing the PreScission protease site were cleaved with recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged HRV 3C (PreScission) protease at a protein/protease mass ratio of 10:1 at 4°C overnight without continued stirring or rocking. After cleavage, the mixture was passed over Strep-Tactin Sepharose and glutathione Sepharose (GE Healthcare) to remove the uncleaved protein, cleaved Strep-tag II, and PreScission protease, and the unbound fraction containing untagged UL21C was collected. Constructs were further purified using size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200, in buffer A), and were stored with 1× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce).

Selenomethionine-containing UL21C was expressed by growing transformed Rosetta cells in M9 minimal medium (1× M9 salts, 0.4% glucose, 2 mM magnesium sulfate, 0.1 mM calcium chloride, 0.2 mg/liter thiamine, 1 mg/liter biotin) at 37°C. At an OD600 of 0.5, lysine, phenylalanine, threonine (100 mg/liter), isoleucine, leucine, valine (50 mg/liter), and selenomethionine (60 mg/liter) were added, and the mixture was shaken for 15 min at 37°C. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG overnight at 20°C. Selenomethionine-containing protein was purified like native protein except that buffer A contained 2 mM TCEP to mitigate selenomethionine oxidation.

Crystallization and structure determination.

Native and selenomethionine-containing UL21C crystals were grown overnight at room temperature by vapor diffusion in hanging drops (2 μl protein at ∼3 mg/ml; 2 μl crystallization solution [17 to 23% polyethylene glycol 3350, 100 mM sodium citrate {pH 3.5 to 4.0}, 0.3 to 0.4 M nondetergent sulfobetaine 256 {Hampton Research}, and 25 mM sodium fluoride]). Crystals were soaked in a cryoprotective solution consisting of the crystallization solution supplemented with 18% sorbitol and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K on beamline 24-ID-C at the Advanced Photon Source at the Argonne National Laboratory and were processed using RAPD (rapid automated processing of data) software (https://github.com/RAPD/RAPD). To locate selenium sites, two highly redundant isomorphous Se SAD (single-wavelength anomalous dispersion) data sets (400° rotation each) were merged using RAPD. Within the RAPD SAD pipeline, the SHELX macromolecular substructure solution program (38) was used to locate selenium sites, and the Phenix AutoSol program (39) was used to calculate experimental phases and generate a preliminary electron density map. An initial model was built manually into the experimental electron density using Coot (40) and was improved through multiple rounds of density modification and phase combination in RESOLVE (39). The resulting model was refined against native data in phenix.refine (39) to 2.7 Å. Model refinement included gradient minimization refinement of xyz coordinates, individual thermal parameters, and translation-libration-screw (TLS) rotation model parameters, with optimization of X-ray/stereochemistry and X-ray/atomic displacement parameter (ADP) weights, all as implemented in phenix.refine. The final Rwork is 21.77%, and Rfree is 23.43%, as defined in Table 2. All statistics are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | Value for: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Native UL21C crystal | Selenomethionine-containing UL21C crystal | |

| Data collection statisticsa | ||

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 54.27, 54.27, 180.76 | 56.06, 56.06, 185.27 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 54.27–2.72 (2.85–2.72) | 185.27–2.88 (3.03–2.88) |

| Rsym or Rmergeb | 0.066 (0.864) | 0.181 (2.481) |

| I/σIc | 20.5 (2.4) | 28.3 (1.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.7) | 100.00 (100.00) |

| Redundancy | 6.7 (7.2) | 50.6 (39.8) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 51.98–2.72 | |

| No. of reflections (free) | 7,813 (360) | |

| Rwork/Rfreed | 0.2177/0.2343 | |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 1,926 | |

| Water | 17 | |

| B factors | ||

| Protein | 51.80 | |

| Water | 49.40 | |

| RMSD | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.003 | |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.685 | |

| Ramachandran plot (%)e | ||

| Favored regions | 97.6 | |

| Allowed regions | 2.4 | |

| Outliers | 0.0 | |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Percent difference among intensities of equivalent reflections.

Ratio of reflection intensity to estimated error, averaged.

Rwork and Rfree are defined as ∑||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/∑|Fobs| for the reflections in the working and the test set, respectively, where Fobs refers to experimental reflection amplitudes and Fcalc refers to amplitudes calculated from the model.

As determined using MolProbity (molprobity.biochem.duke.edu) (53).

Nuclease treatment and RNA gels.

StII-UL21 bound to endogenous E. coli nucleic acids was expressed and purified from 1 liter of E. coli Rosetta cells. The complex was split into three aliquots, from which DNA, RNA, or total nucleic acids were isolated. Total nucleic acids were isolated by phenol-chloroform precipitation. Briefly, equal volumes of phenol-chloroform (125:24:1 ratio of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol; Life Technologies) were added to each sample. The upper aqueous layer was mixed with 10 μg glycogen (Life Technologies), 1/10 volume 3 M sodium acetate, and 3 volumes ethanol and was incubated at −20°C for 30 min. Nucleic acids were pelleted at 16,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min and were washed with 75% ethanol before resuspension in water for analysis. To isolate RNA only, the precipitation was performed using acidic phenol-chloroform, pH 4.5 (5:1; Life Technologies). To isolate DNA only, the complex was treated with RNase A at an RNase A (Invitrogen)/UL21C volume ratio of 1:1,000 for 20 min at 37°C prior to nucleic acid extraction with the neutral pH phenol-chloroform mixture. Two micrograms of precipitated nucleic acid fractions resuspended in water was treated with 2 U of Turbo DNase (Ambion) or 0.4 μg RNase A (Invitrogen) in 1× Turbo DNase buffer with 2 mM calcium chloride for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were analyzed on a denaturing RNA gel. Samples were prepared with 5× RNA sample buffer {4 mM EDTA, 2.7% formaldehyde, 30.8% formamide, 20% glycerol, 40% 10× MOPS buffer [200 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), 30 mM sodium acetate trihydrate, 10 mM EDTA; pH adjusted to 7.0 with sodium hydroxide]} diluted to 1×, 25% FORMAzol (Molecular Research Center, Inc.), and 0.05 mg/ml ethidium bromide. Samples were heated at 85°C for 1 to 3 min, cooled on ice, loaded immediately onto a 1.2% agarose gel prepared in 1× MOPS buffer with 5% formaldehyde, and run at 75 V in 1× MOPS buffer.

Protein structure accession number.

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the UL21C structure have been deposited to the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession number 5ED7.

RESULTS

UL21 is composed of two stable domains.

Full-length HSV-1 strain 17 UL21 expressed in E. coli with an N-terminal StII (Fig. 1A) underwent spontaneous proteolysis by a trypsin-like protease, generating N- and C-terminal fragments (Fig. 1B). The stability of these fragments in combination with predicted secondary structure and sequence alignment suggested that UL21 was composed of two ordered domains—a conserved N-terminal domain (sequence identity, 9.7%; similarity, 25%) (21) and a more variable C-terminal domain (sequence identity, 1.2%; similarity, 8.4%)—connected by a flexible, protease-sensitive linker containing a stretch of conserved sequence predicted to form a β-strand (Fig. 1A). N-terminal sequencing revealed that these fragments correspond to UL21N (residues 1 to 216) (21), UL21C residues 237 to 535 [UL21C(237-535)], and UL21C(281-535) (Fig. 1B).

UL21C construct design.

UL21C(237-535) and UL21C(281-535) (Fig. 1A) were subcloned with N-terminal StII, expressed, and purified. Whereas StII-UL21C(281-535) was insoluble at concentrations above 1 mg/ml, StII-UL21C(237-535) could be concentrated to 4 mg/ml and formed barrel-shaped crystals in 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.2)–1.2 M ammonium phosphate (Fig. 1C). However, on a Coomassie blue-stained gel, both the crystallized protein and the protein that had been exposed to the dispensing nozzle of the crystallization robot migrated as shorter species than the originally purified protein stock (Fig. 1D), indicating that StII-UL21C(237-535) was cleaved upon exposure to the protease-contaminated dispensing nozzle. N-terminal sequencing of the protein stock revealed the crystallized species to be UL21C(275-535). UL21C(275-535) was subcloned with N-terminal StII, but the resulting StII-UL21C(275-535), like StII-UL21C(281-535), was insoluble above 1 mg/ml. To mitigate the poor protein solubility, presumably caused by suboptimal tag placement, an HRV 3C (PreScission) protease cleavage site was inserted between StII and residue 275 to generate the StII-HRV3C-UL21C(275-535) construct. This construct was expressed, purified, separated from StII, concentrated to ∼3 mg/ml, and found to form square prisms in 100 mM sodium citrate (pH 3.5)–19% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 3350 (Fig. 1C). The crystals took space group P43212 and diffracted to 2.7 Å. A selenomethionine derivative of StII-HRV3C-UL21C(275-535) was prepared, crystallized under native conditions, and used to determine the structure of UL21C by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD). There is a single copy of UL21C in the asymmetric unit. The final structure, refined against a 2.7-Å native data set, contains residues 279 to 530 and has an Rwork of 21.77% and an Rfree of 23.43% (Table 2).

UL21C has a unique fold.

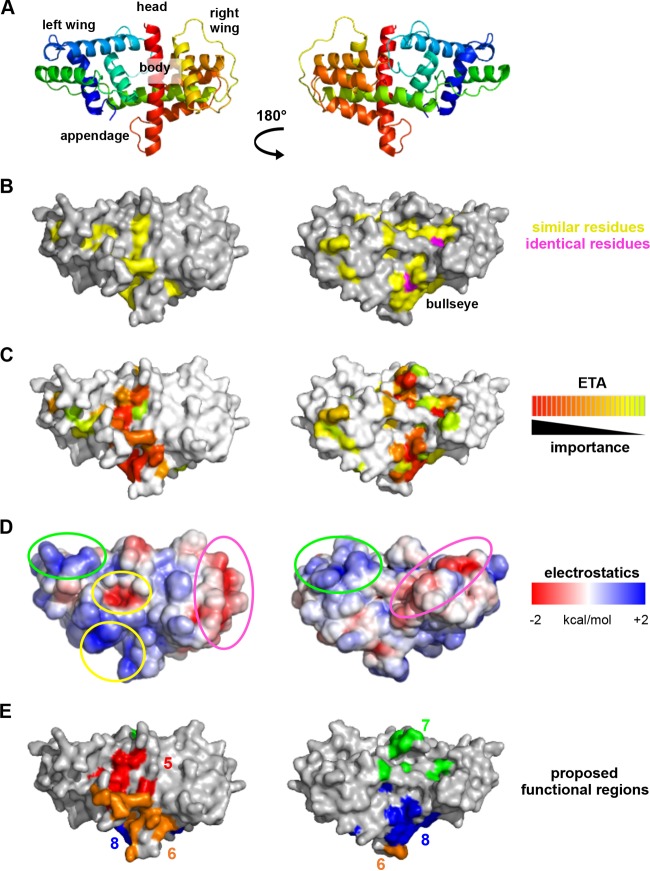

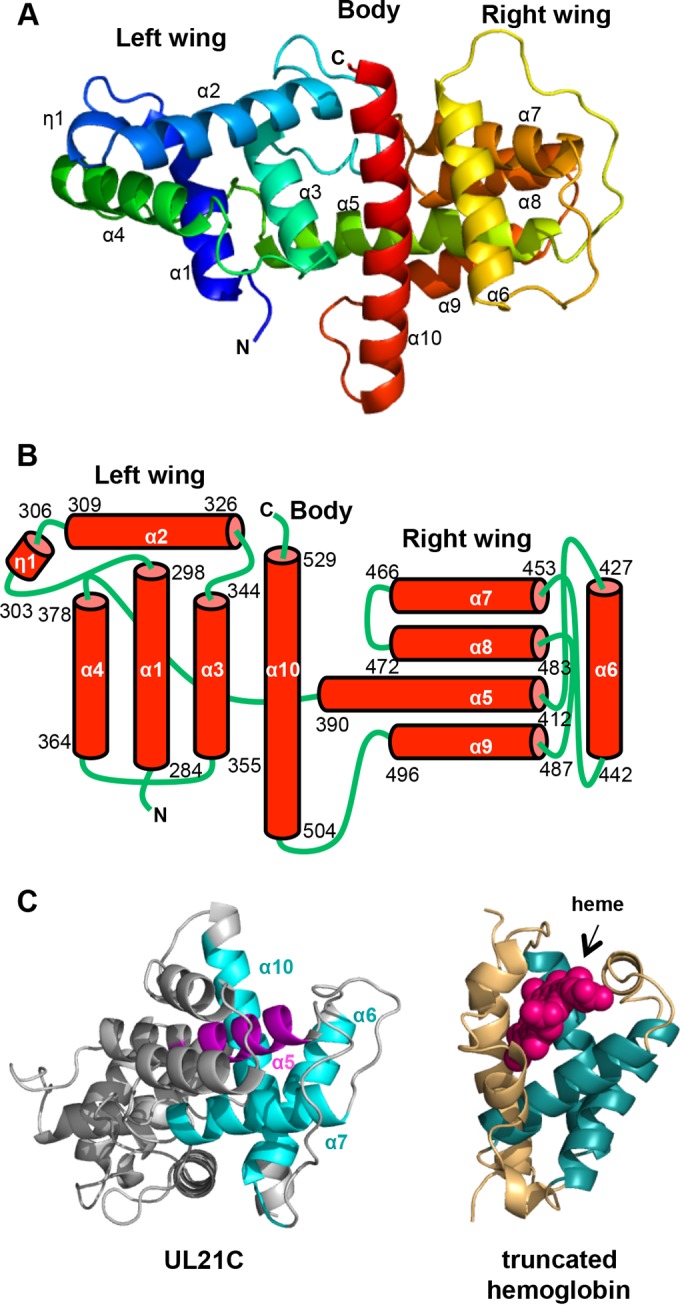

UL21C is composed of 10 α-helices and one 310 helix that are arranged into a dragonfly fold with the left “wing” formed by α1 to α4 and η1, the right “wing” formed by α5 to α9, and the “body” formed by the long helix α10 (Fig. 2A and B). Helices α1, α3, α4, and α6 are aligned approximately parallel to the helix α10 “body,” while helices η1, α2, α5, α7, α8, and α9 lie parallel to each other but perpendicular to helix α10. The boundaries of the helices are mostly in agreement with the secondary structure prediction by PSIPRED (41) except that helices α3, α4, α5, α6, α7, α8, α9, and α10 are between 3 residues shorter and 5 residues longer than predicted. 310 helix η1 was not predicted. The α-helical dragonfly fold does not resemble any known protein folds, according to the Dali structural similarity search algorithm (42). A portion of UL21C displays weak structural similarity to 2/2 globins, also known as truncated hemoglobins, which are small proteins from plants and bacteria that share structural and functional similarity with the globin superfamily (43). Portions of α-helices α6, α7, and α10 in UL21C align with three α-helices in the heme-binding site with a Z score of 4.7 and a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 4.5 Å over 87 aligned residues, but helix α5 in UL21C blocks the would-be heme-binding pocket, which rules out heme binding as a possible function for UL21 (Fig. 2C). Thus, the biological significance of this limited structural similarity, if any, is unclear.

FIG 2.

The structure of HSV-1 UL21C resembles a dragonfly. (A) Ribbon representation of the crystal structure of UL21C. Blue, N terminus; red, C terminus. Helices are numbered sequentially. (B) Diagram of the topology of UL21C. The amino acid boundaries of helices are marked. (C) UL21C is shown side by side with monomeric truncated hemoglobin (PDB accession no. 4UUR). The structures were aligned using the Dali server. Aligned residues in UL21C and truncated hemoglobin are shown in cyan and teal, respectively (RMSD, 4.5 Å over 87 aligned residues). The heme group in truncated hemoglobin is shown in magenta, and the similarly placed helix (α5) in UL21C is shown in purple. All structures were rendered in PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

Areas of conservation and diversity on the UL21C surface.

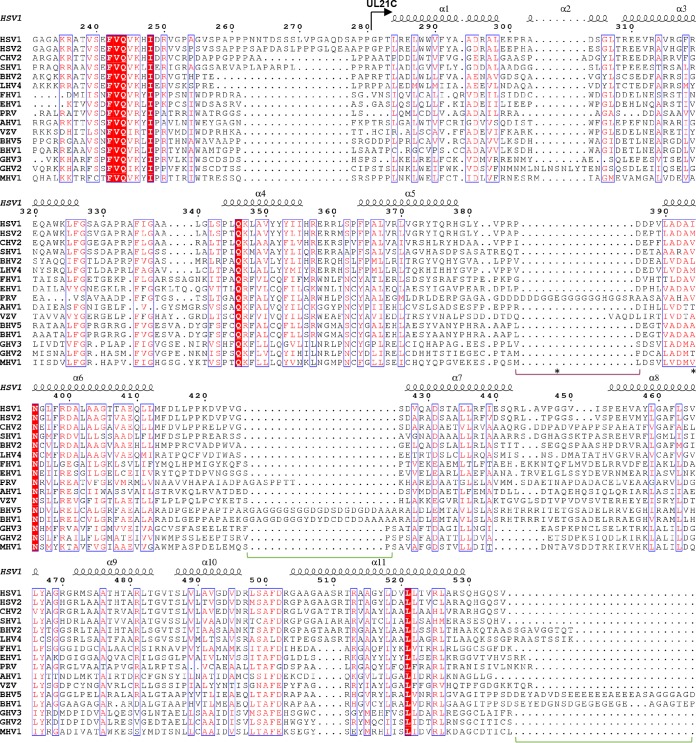

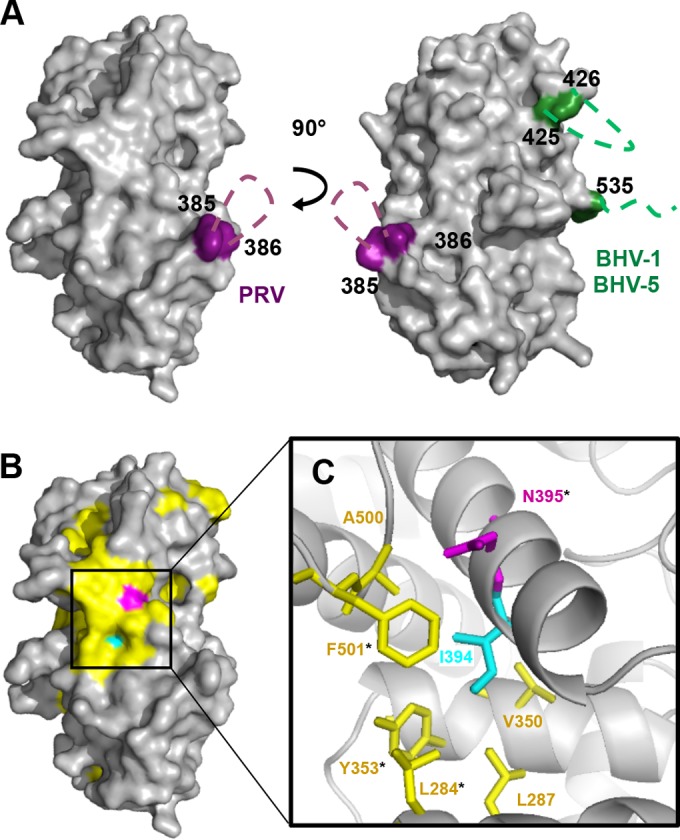

HSV-1 UL21 has 28 residues that are identical among 16 alphaherpesviruses, but only 3 of these residues are within UL21C (Fig. 3). Additionally, the sequence length of UL21C differs across species, since UL21 homologs from PRV, bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1), and BHV-5 contain long insertions at different locations in the sequence. Specifically, the PRV UL21C contains a 17-amino-acid insertion between the residues corresponding to residues 385 and 386 within HSV-1 UL21C, while the C-terminal domains of BHV-1 and BHV-5 UL21 each contain a 23-amino-acid insertion between the residues corresponding to residues 425 and 426 within HSV-1 UL21C and a 28-amino-acid extension after the residue corresponding to residue 535 (Fig. 3). All three insertions are rich in glycines, aspartates, and glutamates and likely form flexible, negatively charged loops in their native structures (Fig. 4A). Such virus-specific surface variability may reflect divergent protein functions.

FIG 3.

Sequence conservation in UL21C. Shown is a multiple-sequence alignment of UL21 homologs from 16 alphaherpesviruses. Only the alignment of residues corresponding to residues 231 to 535 of HSV-1 UL21 is shown. The secondary structures of HSV-1 UL21 and the start of UL21C are marked above the alignment. Identical residues are represented by white letters on a red background. Similar residues are represented by red letters boxed in blue. UL21C sequences share 1.2% identity and 8.4% similarity. Insertions in BHV-1, BHV-5, and PRV homologs are indicated by green or purple brackets, respectively, below the alignment. Residues E355 and V375, mutated in PRV Bartha UL21, are indicated by asterisks below the alignment. Alignment was carried out in ClustalW (51) using sequences from the following viruses (with GenBank accession numbers given in parentheses): human HSV-1 (ACM62243), human HSV-2 (AEV91359), cercopithecine herpesvirus 2 (CHV2) (AAU88086), saimiriine herpesvirus 1 (SHV1) (ADO13807), BHV-2 (AAK69349), leporid herpesvirus 4 (LHV4) (AFR32463), feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV1) (ACT88337), equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV1) (AAT67298), PRV (AAA47475), anatid herpesvirus 1 (AHV1) (ABO26208), varicella-zoster virus (VZV) (AAT07796), BHV-5 (AAR86141), BHV-1 (CAA88112), gallid herpesvirus 3 (GHV3) (AEI00223), gallid herpesvirus 2 (GHV2) (AAF66756), and meleagrid herpesvirus 1 (MHV1) (AAG45758). The figure was made in ESPript (52).

FIG 4.

Conserved and variable regions on the surface of UL21C. (A) Surface representation of UL21C. Two orientations related by a 90° rotation along the vertical axis are shown. Predicted locations of G/D/E-rich loop insertions in PRV (purple), BHV-1, and BHV-5 (green) are indicated by dashed lines. (B) Surface representation of UL21C in the same orientation as that on the left in panel A. Conserved residue N395 is shown in magenta, and similar residues from the alignment in Fig. 3 are shown in yellow. Residue I394, which corresponds to PRV UL21 residue V375 (mutated in the Bartha strain), is shown in cyan. (C) Close-up view of residue I394 and its van der Waals interactions within the hydrophobic core with residues L284, L287, V350, Y353, A500, and F501. Surface-accessible residues are marked with asterisks. The color scheme is the same as that in panel B.

The three identical residues in UL21C are Q346, N395, and L521 (Fig. 3). The side chain of L521 is buried and is likely necessary for structural integrity. In contrast, the side chains of Q346 and N395 are mostly surface accessible and could be functionally important. N395 is noteworthy because it is surrounded by conserved residues, generating a “bull's eye” pattern (Fig. 4B). Three coding mutations—H37R, E355D, and V375A—have been identified in UL21 in the avirulent, spread-deficient PRV strain Bartha (35). When these mutations were reverted to the wild-type sequence, defects in spread (34) and virulence (35) were also reversed, suggesting that these residues have functional roles. Two of these mutations, E355D and V375A, map to the C-terminal domain of UL21. While E355 in PRV UL21 is located within the G/D/E-rich insertion absent from HSV-1 UL21, V375 aligns with I394 in HSV-1 UL21. The side chain of I394 is mostly buried within the hydrophobic core underlying N395, where it engages in van der Waals interactions with the side chains of several conserved residues that surround N395 (Fig. 4C). The valine-to-alanine mutation at this position in the PRV UL21 homolog would be expected to destabilize the hydrophobic core and thus “deflate” the conserved surface above it, which may disrupt the binding of a potential functional partner. Thus, the conserved surface surrounding N395 could be essential for a function related to virulence.

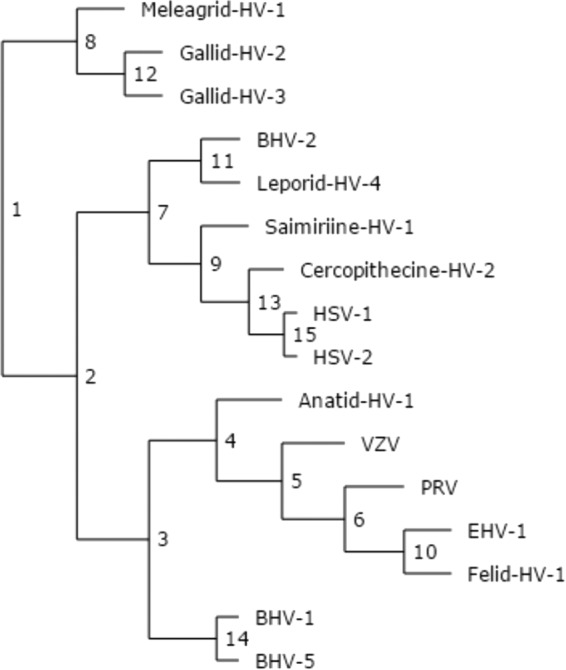

To uncover additional conservation patterns within UL21C, we performed evolutionary trace analysis (ETA), a method of identifying functionally important residues on the basis of their resistance to mutations over evolutionary time (44), as has been done for herpesvirus proteins UL25 (45), UL37N (46), and UL21N (21). After an evolutionary tree (Fig. 5) had been generated from the 16 aligned sequences (Fig. 3), ETA highlighted surface clusters of evolutionarily conserved residues that formed a belt wrapping around the middle of UL21C (Fig. 6C), parallel to the long central helix α10 (Fig. 6A).

FIG 5.

Phylogenetic tree of UL21, from universal evolutionary trace analysis (http://mammoth.bcm.tmc.edu/uet/) of full-length UL21 homologs from 16 alphaherpesviruses. Partition numbers are marked at each branching point.

FIG 6.

Surface analysis of the structure of UL21C. UL21C is shown in two orientations that are related by a 180° rotation around the vertical axis. (A) Ribbon diagram with topological descriptors. (B) Surface representation, with similar residues shown in yellow and identical residues in magenta. (C) Evolutionarily conserved residues identified using universal evolutionary trace analysis (http://mammoth.bcm.tmc.edu/uet/) are mapped on the surface of UL21C. Residues with importance scores in the top 25% were assigned colors from red (more conserved) to yellow (less conserved). (D) Electrostatic surface potential was analyzed by composing a map of the surface of UL21C using the PBEQ Solver function in the CHARMM program (http://www.charmm-gui.org/?doc=input/pbeqsolver). The two nonconserved acidic valleys wrap around the “wings” of UL21C and are circled in fuchsia; the two nonconserved basic patches sit on the tips of the “wings” and are circled in green; and the conserved acidic patch and the conserved nearby basic pocket are circled in yellow. (E) Potential functional regions on the surface of UL21C. Region 5 (red) includes Q321, Y352, E358, P363, D519, and L526; region 6 (orange), R357, R359, R360, E409, A500, R503, A509, R511, T512, R513, and A515; region 7 (green), D295, G330, P332, R333, Q346, K347, and G469; and region 8 (blue), L284, Y353, D392, N395, R399, D400, D494, S499, F501, and D502.

The surface of UL21C contains acidic and basic patches, some of which are conserved.

Analysis of the electrostatic surface potential identified three acidic patches on the surface of HSV-1 UL21C (Fig. 6D). One acidic patch maps to an area within the evolutionarily conserved belt around the “body” of the protein and may contribute to a common UL21 function. The other two acidic patches, which are located in valleys on either “wing” (Fig. 6D), are not evolutionarily conserved and could participate in virus-specific functions.

The surface of HSV-1 UL21C has 27 arginines and 3 lysines (Fig. 3), which is consistent with the calculated pI of 9.68 (Table 3), and some of these residues cluster into three prominent basic patches. Only one basic patch is located within the evolutionarily conserved belt (Fig. 6D), while the two nonconserved basic patches map to “wing” tips. Interestingly, both the basic pI and 12 arginines are conserved in HSV-2 and the other four most evolutionarily similar viruses that cluster at partition 2 of ETA (Fig. 5 and 6) but are not conserved among more divergent alphaherpesviruses, such as PRV and VZV, which have acidic calculated pIs. Such a divergence in charge among UL21C homologs is notable in contrast to the more clustered isoelectric points of both UL21N and the UL21 binding partner, UL16 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Isoelectric points of UL16 and UL21 sequences from 16 alphaherpesviruses

| Alphaherpesvirusa | pI of sequence |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| UL21 |

UL16 (full) |

||

| C-terminal domain | N-terminal domain | ||

| Meleagrid HV-1 | 4.78 | 4.94 | 6.77 |

| Gallid HV-2 | 4.62 | 5.07 | 7.11 |

| Gallid HV-3 | 4.88 | 5.13 | 8.89 |

| BHV-2 | 9.34 | 5.97 | N/A |

| Leporid HV-4 | 8.71 | 7.64 | 7.50 |

| Saimiirine HV-1 | 8.37 | 5.41 | 6.82 |

| Cercopithecine HV-2 | 7.22 | 5.96 | 8.35 |

| HSV-1 | 9.68 | 5.20 | 8.06 |

| HSV-2 | 8.10 | 6.43 | 7.90 |

| Anatid HV-1 | 4.82 | 5.05 | 7.95 |

| VZV | 5.78 | 5.23 | 8.74 |

| PRV | 4.92 | 5.20 | 8.53 |

| EHV-1 | 5.12 | 5.07 | 8.72 |

| Felid HV-1 | 5.33 | 4.84 | 6.17 |

| BHV-1 | 4.81 | 8.14 | 9.37 |

| BHV-5 | 4.77 | 5.94 | 9.37 |

HV, herpesvirus. Boldface indicates basic sequences.

Potential functional regions in UL21C.

By combining the results of the analyses presented above, we located four conserved regions of potential functional importance on the surface of UL21C (Fig. 6E), designated regions 5 to 8 (which join conserved regions 1 to 4 located within UL21N [21]). Region 5 surrounds the conserved acidic patch near the center of the “body.” Region 6 contains the conserved basic patch on one side of the “appendage.” Region 7 lies atop the “head” and includes evolutionarily conserved residues identified by ETA. Region 8 completes the belt of evolutionarily conserved residues and encompasses the bull's eye near the “appendage.” Together, these regions wrap around the middle of UL21C and may mediate conserved functions of UL21C.

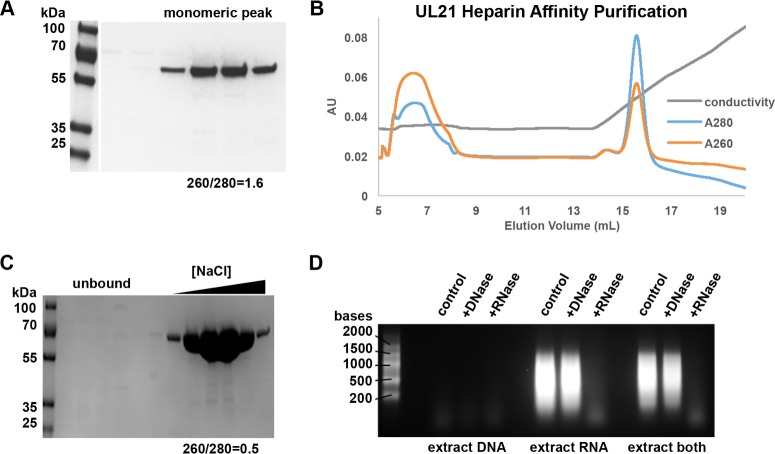

UL21 and UL21C copurify with E. coli RNA.

While purifying UL21, we observed that after the Strep-Tactin affinity and size exclusion chromatography purification steps, the UL21 sample appeared homogenous as judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7A) but had a spectroscopic A260/A280 ratio of 1.6, which is characteristic of a sample that contains approximately 80% protein and 20% nucleic acid (NA) (47). This suggested that a large amount of E. coli NAs copurified with UL21. These NAs could be separated from UL21 only by use of heparin resin, which binds UL21 (Fig. 7B) but not NAs. The resulting UL21 sample (Fig. 7C) had an A260/A280 ratio of 0.5, which is consistent with a homogenous protein sample. Similar results were also observed with UL21C constructs, whereas UL21N did not copurify with substantial amounts of NAs. To identify the type of NAs copurifying with UL21, the UL21/NA complex was affinity purified, and bound NAs were precipitated, digested with nucleases, and resolved on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. The NAs were susceptible to digestion by RNase but not DNase (Fig. 7D). We conclude that UL21 preferentially binds RNA through its C-terminal domain.

FIG 7.

UL21 binds E. coli RNA. (A) Purified StII-GS-UL21 expressed in E. coli appears homogenous as judged by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining but has an A260/A280 ratio consistent with a large amount of nucleic acid contaminant. (B) UL21 binds heparin Sepharose and is eluted with increasing NaCl concentrations (shown as conductivity). (C) Heparin Sepharose purification produces pure UL21 free of nucleic acid contamination as judged by the A260/A280 ratio and SDS-PAGE. (D) The copurified nucleic acids are susceptible to digestion with RNase but not DNase. Samples were resolved on an ethidium bromide-stained formaldehyde agarose gel.

DISCUSSION

UL21 has been implicated in a number of processes in the viral replication cycle, including nuclear egress, cytoplasmic capsid trafficking, secondary envelopment, and cell-cell spread, yet the molecular mechanisms by which UL21 enables these and other processes remain unknown. Here we determined and analyzed the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of HSV-1 UL21, which, together with the previously determined structure of the N-terminal domain of UL21 (21), provides a 3-dimensional template for systematic exploration of the multiple activities of UL21.

The constructs used to determine the structure of UL21C, as well as that of UL21N before it, were designed based on the products of accidental proteolysis that occurred during purification. The proteolytic susceptibility of this protein in vitro has been observed previously (21, 30, 36), typically with affinity-tagged protein constructs expressed in E. coli. One study observed a potential proteolytically processed UL21 species in immunoprecipitates from PRV-infected cells (29); however, at 40 kDa, this species is larger than any stable cleavage product of UL21 predicted from the structures of the two domains. Therefore, there is little evidence that proteolysis occurs during infection. Taken together with the secondary-structure prediction, the proteolytic instability of full-length UL21 in vitro, along with the relative stability of UL21N and UL21C, supports a model in which UL21 is composed of two distinct domains connected by a flexible linker, a structure reminiscent of two balls connected by a string. Whether UL21N and UL21C interact, and whether this interaction is dynamically regulated, is unknown. UL21N and UL21C could interact through electrostatic interactions, because HSV-1 UL21N is largely acidic (21) whereas HSV-1 UL21C is basic (this study); however, this potential interaction could feasibly be blocked by binding partners of UL21, e.g., UL16. Future experiments must address the spatial and temporal relationships between the domains of UL21 as well as the utility of the highly conserved and likely important amino acid stretch located within the linker region.

The basic patches on the surface of HSV-1 UL21C may explain why UL21 is found in the nucleus in transfected and infected cells (28–30, 32, 36). Although the UL21 sequence lacks an obvious linear classical nuclear localization signal (cNLS), one of the positively charged surface areas could structurally mimic an NLS or provide a nonclassical NLS. For example, monomers of STAT1 are unable to bind importin α for nuclear import, but through dimerization, an NLS is formed out of residues from each monomer and allows the dimer to bind importin α (48). Since the evolutionarily distant UL21 proteins from HSV-1 and PRV are both found in the nucleus (28–30, 32, 36), we could potentially identify a putative basic NLS on the surface of UL21 by mapping the few arginines and lysines conserved between HSV-1 and PRV sequences; however, these are spread around the surface of the molecule, and therefore, there is no obvious cluster that could represent a basic nuclear localization signal. Alternatively, UL21 could localize to the nucleus by piggybacking on a cellular protein containing an NLS.

Like UL21N (21), UL21C has a unique fold. Whether this property enables functions unique to alphaherpesviruses or provides a new way to perform a function mediated by other, unrelated protein structures is unknown. UL21 is thought to participate in different processes during the viral replication cycle. To provide a starting point for mutational analysis, we have designated four surface regions within UL21C that could have functional roles. If UL21C interacts with UL21N, one potential conserved function could be binding to UL21N, which has a higher degree of sequence conservation than UL21C. Another conserved function could be interaction with UL16 (25, 30, 31); however, UL16 sequences could have evolved in parallel with UL21C sequences such that while formation of the complex is conserved, the binding interface is not. UL21C binds capsid (28, 29), and since this has been seen in both HSV-1 and PRV, direct or indirect capsid binding is likely a conserved function.

In contrast to the more conserved UL21N (21), the surface of UL21C shows a great deal of variation among homologs, as is evident from both sequence similarity and evolutionary conservation. Hence, we hypothesize that while UL21N may mediate conserved functions, UL21C additionally facilitates functions that adapt the virus to its specifically preferred host. These virus-specific characteristics of UL21C are also apparent in its electrostatic properties. First, there is a stark division among the calculated isoelectric points of UL21Cs: the 5 sequences most closely related to HSV-1 UL21C (Fig. 5; Table 3) are basic, while the rest of the sequences are acidic. These differences can be localized to three basic regions (Fig. 6) on the surface of HSV-1 UL21C that appear specific to the 6 basic UL21 homologs, including HSV-1, but not to the 10 acidic UL21 homologs (Table 3).

Sequence analysis revealed acidic glycine-rich insertions in the sequences of PRV, BHV-1, and BHV-5 that are absent from other UL21 homologs. The insertion in PRV UL21, which likely forms a flexible loop (Fig. 4), was previously hypothesized to serve as a hinge and site of proteolytic processing (29, 36), based on the inherent flexibility of glycine residues and the similarity between this sequence and the proteolytic processing sequence found in HSV-1 ribonucleotide reductase (49). While this loop or the similar loops in BHV-1 and BHV-5 may be cleaved in the cell, based on the structure of HSV-1 UL21 presented here, it is unlikely that this cleavage would result in separation of the domain, since it would expose many hydrophobic residues.

The ability of UL21 to bind RNA through its C-terminal domain was unexpected, based on the previous observation that there are four HSV-1 proteins that bind total RNA from infected cells in a Northwestern assay: US11, UL49, UL47, and an unidentified 110-kDa protein that is too large to represent any known species of UL21 (18). This conclusion, however, does not rule out the possibility that UL21 is an RNA-binding protein. Since UL47 and UL49 are among the most abundant proteins in the tegument (15) and would therefore be easily detected, it is possible that the amount of UL21 in the virion is too small to be detected by this analysis. Alternately, the UL21–RNA binding interaction may require specific structures that would have been sensitive to the multiple denaturation and renaturation steps required in this technique. While the precise location of the RNA binding site awaits experimental validation, RNA, being a negatively charged polymer, could, in principle, bind to any of the three prominent basic patches in HSV-1 UL21 (Fig. 6C). Whether RNA binding is conserved among all UL21 homologs or is limited to the species with basic isoelectric points (Table 3) is still unknown.

So far, this phenomenon has been observed only with E. coli RNA, and further studies are necessary to identify the biologically relevant RNA target of UL21 and to fully characterize the UL21–RNA interaction. Interestingly, in the absence of UL21 in HSV-1 (22) and HSV-2 (20), there is a delay in the production of viral RNA and proteins. It is tempting to speculate that this delay in viral RNA and protein production could reflect a role for UL21 in transcription and/or translation. Moreover, UL21C appears to contribute to the virulence of PRV, because infection with a UL21C deletion mutant increased the time to death for infected mice approximately 3-fold (29). Thus, UL21 could potentially play a central role in regulating viral replication, joining the growing number of HSV tegument proteins known to serve both structural and regulatory functions in herpesviral replication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John Wills and Pooja Chadha for initial cloning of the full-length UL21 plasmid and helpful discussions, NE-CAT staff for help with X-ray data collection, and Marta Gaglia for help with RNA experiments. We also thank Peter Cherepanov for the gift of the GST-PreScission protease expression plasmid and Jared Pitts and Janna Bigalke for purifying PreScission protease.

This work is based on research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on the 24-ID-C beamline is funded by an NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by the Argonne National Laboratory under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. All software was installed and maintained by SBGrid (50).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desai PJ. 2000. A null mutation in the UL36 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 results in accumulation of unenveloped DNA-filled capsids in the cytoplasm of infected cells. J Virol 74:11608–11618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11608-11618.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs W, Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. 2004. Essential function of the pseudorabies virus UL36 gene product is independent of its interaction with the UL37 protein. J Virol 78:11879–11889. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11879-11889.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai P, Sexton GL, McCaffery JM, Person S. 2001. A null mutation in the gene encoding the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL37 polypeptide abrogates virus maturation. J Virol 75:10259–10271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10259-10271.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mundt E, Mettenleiter TC. 2001. Pseudorabies virus UL37 gene product is involved in secondary envelopment. J Virol 75:8927–8936. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.8927-8936.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandbaumhüter M, Dohner K, Schipke J, Binz A, Pohlmann A, Sodeik B, Bauerfeind R. 2013. Cytosolic herpes simplex virus capsids not only require binding inner tegument protein pUL36 but also pUL37 for active transport prior to secondary envelopment. Cell Microbiol 15:248–269. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luxton GW, Lee JI, Haverlock-Moyns S, Schober JM, Smith GA. 2006. The pseudorabies virus VP1/2 tegument protein is required for intracellular capsid transport. J Virol 80:201–209. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.201-209.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaichick SV, Bohannon KP, Hughes A, Sollars PJ, Pickard GE, Smith GA. 2013. The herpesvirus VP1/2 protein is an effector of dynein-mediated capsid transport and neuroinvasion. Cell Host Microbe 13:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kattenhorn LM, Korbel GA, Kessler BM, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. 2005. A deubiquitinating enzyme encoded by HSV-1 belongs to a family of cysteine proteases that is conserved across the family Herpesviridae. Mol Cell 19:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuchs W, Granzow H, Klupp BG, Kopp M, Mettenleiter TC. 2002. The UL48 tegument protein of pseudorabies virus is critical for intracytoplasmic assembly of infectious virions. J Virol 76:6729–6742. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6729-6742.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinheimer SP, Boyd BA, Durham SK, Resnick JL, O'Boyle DR II. 1992. Deletion of the VP16 open reading frame of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol 66:258–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mossman KL, Sherburne R, Lavery C, Duncan J, Smiley JR. 2000. Evidence that herpes simplex virus VP16 is required for viral egress downstream of the initial envelopment event. J Virol 74:6287–6299. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.14.6287-6299.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell ME, Palfreyman JW, Preston CM. 1984. Identification of herpes simplex virus DNA sequences which encode a trans-acting polypeptide responsible for stimulation of immediate early transcription. J Mol Biol 180:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batterson W, Roizman B. 1983. Characterization of the herpes simplex virion-associated factor responsible for the induction of α genes. J Virol 46:371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott G, Mouzakitis G, O'Hare P. 1995. VP16 interacts via its activation domain with VP22, a tegument protein of herpes simplex virus, and is relocated to a novel macromolecular assembly in coexpressing cells. J Virol 69:7932–7941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb WW, Jones LM, Dee A, Chaudhry F, Brown JC. 2012. Role of a reducing environment in disassembly of the herpesvirus tegument. Virology 431:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnelly M, Elliott G. 2001. Fluorescent tagging of herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP13/14 in virus infection. J Virol 75:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2575-2583.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly M, Elliott G. 2001. Nuclear localization and shuttling of herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP13/14. J Virol 75:2566–2574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2566-2574.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donnelly M, Verhagen J, Elliott G. 2007. RNA binding by the herpes simplex virus type 1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein UL47 is mediated by an N-terminal arginine-rich domain that also functions as its nuclear localization signal. J Virol 81:2283–2296. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01677-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sciortino MT, Taddeo B, Poon AP, Mastino A, Roizman B. 2002. Of the three tegument proteins that package mRNA in herpes simplex virions, one (VP22) transports the mRNA to uninfected cells for expression prior to viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:8318–8323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122231699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Sage V, Jung M, Alter JD, Wills EG, Johnston SM, Kawaguchi Y, Baines JD, Banfield BW. 2013. The herpes simplex virus 2 UL21 protein is essential for virus propagation. J Virol 87:5904–5915. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03489-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metrick CM, Chadha P, Heldwein EE. 2015. The unusual fold of herpes simplex virus 1 UL21, a multifunctional tegument protein. J Virol 89:2979–2984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03516-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbong EF, Woodley L, Frost E, Baines JD, Duffy C. 2012. Deletion of UL21 causes a delay in the early stages of the herpes simplex virus 1 replication cycle. J Virol 86:7003–7007. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00411-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muto Y, Goshima F, Ushijima Y, Kimura H, Nishiyama Y. 2012. Generation and characterization of UL21-null herpes simplex virus type 1. Front Microbiol 3:394. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klopfleisch R, Klupp BG, Fuchs W, Kopp M, Teifke JP, Mettenleiter TC. 2006. Influence of pseudorabies virus proteins on neuroinvasion and neurovirulence in mice. J Virol 80:5571–5576. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02589-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klupp BG, Bottcher S, Granzow H, Kopp M, Mettenleiter TC. 2005. Complex formation between the UL16 and UL21 tegument proteins of pseudorabies virus. J Virol 79:1510–1522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1510-1522.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meckes DG Jr, Marsh JA, Wills JW. 2010. Complex mechanisms for the packaging of the UL16 tegument protein into herpes simplex virus. Virology 398:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michael K, Klupp BG, Karger A, Mettenleiter TC. 2007. Efficient incorporation of tegument proteins pUL46, pUL49, and pUS3 into pseudorabies virus particles depends on the presence of pUL21. J Virol 81:1048–1051. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01801-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takakuwa H, Goshima F, Koshizuka T, Murata T, Daikoku T, Nishiyama Y. 2001. Herpes simplex virus encodes a virion-associated protein which promotes long cellular processes in over-expressing cells. Genes Cells 6:955–966. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wind N, Wagenaar F, Pol J, Kimman T, Berns A. 1992. The pseudorabies virus homology of the herpes simplex virus UL21 gene product is a capsid protein which is involved in capsid maturation. J Virol 66:7096–7103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harper AL, Meckes DG Jr, Marsh JA, Ward MD, Yeh PC, Baird NL, Wilson CB, Semmes OJ, Wills JW. 2010. Interaction domains of the UL16 and UL21 tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus. J Virol 84:2963–2971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02015-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loomis JS, Courtney RJ, Wills JW. 2003. Binding partners for the UL11 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol 77:11417–11424. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11417-11424.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han J, Chadha P, Starkey JL, Wills JW. 2012. Function of glycoprotein E of herpes simplex virus requires coordinated assembly of three tegument proteins on its cytoplasmic tail. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:19798–19803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212900109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson DC, Baines JD. 2011. Herpesviruses remodel host membranes for virus egress. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:382–394. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curanović D, Lyman MG, Bou-Abboud C, Card JP, Enquist LW. 2009. Repair of the UL21 locus in pseudorabies virus Bartha enhances the kinetics of retrograde, transneuronal infection in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 83:1173–1183. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02102-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klupp BG, Lomniczi B, Visser N, Fuchs W, Mettenleiter TC. 1995. Mutations affecting the UL21 gene contribute to avirulence of pseudorabies virus vaccine strain Bartha. Virology 212:466–473. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baines JD, Koyama AH, Huang T, Roizman B. 1994. The UL21 gene products of herpes simplex virus 1 are dispensable for growth in cultured cells. J Virol 68:2929–2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heckman KL, Pease LR. 2007. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc 2:924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldrick GM. 2008. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A 64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. 2013. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W349–W357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. 2010. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pesce A, Bolognesi M, Nardini M. 2013. The diversity of 2/2 (truncated) globins. Adv Microb Physiol 63:49–78. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407693-8.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lichtarge O, Bourne HR, Cohen FE. 1996. An evolutionary trace method defines binding surfaces common to protein families. J Mol Biol 257:342–358. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowman BR, Welschhans RL, Jayaram H, Stow ND, Preston VG, Quiocho FA. 2006. Structural characterization of the UL25 DNA-packaging protein from herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol 80:2309–2317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2309-2317.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pitts JD, Klabis J, Richards AL, Smith GA, Heldwein EE. 2014. Crystal structure of the herpesvirus inner tegument protein UL37 supports its essential role in control of viral trafficking. J Virol 88:5462–5473. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00163-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joint Proteomics Library of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia. 2006. Measuring protein concentration in the presence of nucleic acids by A280/A260: the method of Warburg and Christian. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2006(1):pii:pdb.prot4252. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fagerlund R, Melen K, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. 2002. Arginine/lysine-rich nuclear localization signals mediate interactions between dimeric STATs and importin α5. J Biol Chem 277:30072–30078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ingemarson R, Lankinen H. 1987. The herpes simplex virus type 1 ribonucleotide reductase is a tight complex of the type α2 β2 composed of 40K and 140K proteins, of which the latter shows multiple forms due to proteolysis. Virology 156:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morin A, Eisenbraun B, Key J, Sanschagrin PC, Timony MA, Ottaviano M, Sliz P. 2013. Collaboration gets the most out of software. eLife 2:e01456. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sievers F, Higgins DG. 2014. Clustal Omega, accurate alignment of very large numbers of sequences. Methods Mol Biol 1079:105–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robert X, Gouet P. 2014. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB III, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]