ABSTRACT

Background and Purpose

Rotator cuff tendinopathy (RTCT) is regularly treated by the physical therapist. Multiple etiologies for RTCT exist, leading an individual to seek treatment from their provider of choice. Strengthening exercises (SE) have been reported to be effective in the treatment of RTCT, but there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of dry needing (DN) for this condition. The purpose of this retrospective case series was to investigate DN to various non-trigger point-based anatomical locations coupled with strengthening exercises (SE) as a treatment strategy to decrease pain and increase function in healthy patients with chronic RTC pathology.

Case Descriptions

Eight patients with RTCT were treated 1-2 times per week for up to eight weeks, and no more than sixteen total treatment sessions of SE and DN. Outcomes were tested at baseline and upon completion of therapy. A long-term outcome measure follow up averaging 8.75 months (range 3 to 20 months) was also performed. The outcome measures included the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the Quick Dash (QD).

Outcomes

Clinically meaningful improvements in disability and pain in the short term and upon long-term follow up were demonstrated for each patient. The mean VAS was broken down into best (VASB), current (VASC), and worst (VASW) rated pain levels and the mean was calculated for the eight patients. The mean VASB improved from 22.5 mm at the initial assessment to 2.36 mm upon completion of the intervention duration. The mean VASC improved from 28.36 mm to 5.0 mm, and the mean VASW improved from 68.88 mm to 13.25 mm. At the long-term follow up (average 8.75 months), The mean VASB, VASC, and VASW scores were 0.36 mm, 4.88 mm, and 17.88 mm respectively. The QDmean for the eight patients improved from 43.09 at baseline to 16.04 at the completion of treatment. At long-term follow-up, the QDmean was 6.59.

Conclusion

Clinically meaningful improvements in pain and disability were noted with the intervention protocol. All subjects responded positively to the intervention and reported quality of life was improved for each subject. The results of this case series show promising outcomes for the combination of SE and DN in the treatment of chronic RTCT.

Level of Evidence

Level 4

Keywords: Dry needling, rotator cuff tendinopathy, shoulder pain

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Shoulder pain is a common condition treated by Physical Therapists (PTs). It is the third most common condition treated by PTs following low back pain and neck pain.1 In the year 2000, the direct costs for the treatment of shoulder dysfunction in the United States totaled $7 billion.2 Shoulder pain occurs as a result of of many different etiologies, and according to Magarey et al, the ability of a PT to accurately diagnose specific pathology in the clinic was inconsistent at best when compared to arthroscopic findings.3 Add this information to the lack of evidence supporting a specific exercise protocols and various “manual therapy” techniques to properly prescribe a rehabilitative program in the treatment of various shoulder conditions, evidence-based rehabilitation prescriptions unfortunately are scarce at best.4–9 In this age of evidence-based practice, therapists must have a foundation in best evidence to treat one of the most common conditions seen clinically.

The rotator cuff (RTC) performs multiple functions during shoulder movements, including glenohumeral abduction (ABD), external rotation (ER) and internal rotation (IR). The RTC also provides stability to the glenohumeral joint and controls translation of the humeral head. The infraspinatus and subscapularis muscles play major roles when the shoulder is abducted in the scapular plane, generating forces that are two to three times greater than supraspinatus force.10 The supraspinatus still remains more effective in ABD of the humerus due to having a more effective moment arm.10 The deltoid muscle and RTC provide significant ABD torque, and these forces are generated not only to ABD the humerus, but also to stabilize the glenohumeral joint and counter the antagonistic muscle actions or compensatory actions when pain or weakness is present.10 Relatively high force from the rotator cuff not only helps ABD the shoulder but also neutralizes the superiorly directed force generated by the deltoids at lower abduction angles.10 This all plays an important role when the RTC is kinematically out of sync due to pain and/or weakness associated with RTC tendinopathy, especially once this condition becomes chronic and compensatory activities of the shoulder complex become the preferred movement pattern employed by the body.

Dry needling (DN) research continues to be sought in the therapy community regarding its effectiveness as a treatment strategy for various conditions. Currently, there is a paucity of randomized control trials (RCT) that exists investigating the effectiveness of DN used with electrical stimulation for treatment of shoulder RTC tendinopathy. According to a recent case series, no recent systematic reviews regarding the effectiveness of dry needling for trigger points (TrPs) and myofascial pain syndromes have noted positive clinical responses to DN interventions.11 Rha et al investigated plasma-rich-platelet (PRP) injections versus DN with ultrasound guided injections into the supraspinatus tendon and found both had positive outcomes with regard to function and symptom relief (though PRP was superior at six months for symptomatic relief and functional improvement).12 To date, the majority of the studies examining the effectiveness of DN intervention have focused on TrP issues as the origin of pain.13–62 Among the DN studies published, few have looked at the effectiveness of DN outside of the TrP realm. Therefore, it seems researchers have neglected to look at the musculo-tendinous and osseo-tendinous junctions of the RTC for DN intervention, which is what clinicians are typically attempting to influence with exercise and manual therapy interventions, versus regularly focusing on treating TrP's for shoulder pain.

Fenwick et al presented the following important information, specific to this case series, regarding the vascularity of tendons: 1) mature tendon are poorly vascularized and rely more on synovial fluid diffusion than vascular perfusion for nutrition; 2) vessels at the tendon-bone insertion anastomose with vessels of the periosteum, forming a indirect link with the osseous circulation; and 3) grafted tendons, after lengthy periods of time, are histologically identical to the original tendon.63 It has been long though that the supraspinatus, in particular has a specific de-vasdcularized region, which could be the reason for it's implication in a majority of RTC pathologies, but evidence has since questioned the validity of this thought process. 63 The vascular supply to tendons has been demonstrated to arise from three specific regions: the musculotendinous junction; the tendino-osseous junction; and vessels from the surrounding tissues including the paratenon, mesotenon, and the vincula.63 If this is the case, it stands to reason that DN to the musculotendinous and tendino-osseous junctions could play a role in pain mitigation and healing of chronic RTC tendinopathies.

Both myofascial DN and TrP-DN terminology is commonly being used to denote DN intervention, yet DN is not just limited to myofascial pain or TrP intervention.11 DN is commonly used for the treatment of myofascial pain and TrPs, but may also be beneficial to treat peri-neural conditions, intramuscular conditions, symptomatic scar tissue and other various conditions that might benefit from the use of DN.11,12,64 Given the paucity of evidence for the use of DN that is not TrP directed, there is a need for the documentation and presentation of clinically relevant interventions that can assist in the treatment of chronic RCT pain. The purpose of this retrospective case series was to investigate DN to various non-TrP-based anatomical locations coupled with strengthening exercises (SE) as a treatment strategy to decrease pain and increase function in healthy patients with chronic RTC pathology.

CASE DESCRIPTIONS

The case series included eight patients with chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy of duration > 90 days. A retrospective review of patients for this case series included those patients who performed the exact protocol chosen for this case series, which the author does not always use for every person to avoid “cookie cutter” therapy. There were no specific inclusion/ exclusion criteria, as would be used for a randomized control trial.

All eight patients were regularly engaged in exercise of some type for health and social engagement at least four times per week. Subjective questions were asked of each patient, and included thorough questioning about sleep deficit due to pain, limitations in lifting/ reaching, exercise limitations, and impaired self-care abilities due to pain, such as dressing and bathing, to provide the author with an idea of self-reported functional limitations. A review of patient histories found several common functional deficits including difficulty sleeping due to pain caused by rolling onto the affected side, limited functional use of the involved upper extremity with exercise and lifting items such as a gallon of milk due to pain and strength deficits, and other various self-care activities. The patients were all in good relative health without serious underlying pathology. A few of the patients had been previously treated by physicians and physical therapists for interventions including, but not limited to: corticosteroid injections and/ or “traditional” physical therapy interventions including stretching and exercise activities, light and deep friction tissue mobilization (such as cross-friction massage/ myofascial release techniques), and therapeutic ultrasound. All had taken or were currently taking over-the-counter NSAIDs for pain mitigation. Patients had not been treated for at least two months prior to the intervention for this retrospective case series. Temporary relief was reported with the previous treatment strategies, but pain had not been eliminated and there was no long-term improvement per subjective reports by each of the patients. Informed consent to participate in the series was retrospectively obtained from the patients. Human subjects research review was not required for this case series. Patients were advised that all HIPPA protected health information standards would be upheld and none of their identifying information would be released per the policies and procedures of the clinic where the treatment was performed.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION 1

Given the fact all eight patients had 1) previous treatment consisting of SE (either self treatment or therapist-guided), and 2) chronic shoulder pain since that time, the patients were considered appropriate for inclusion in the case series to examine the effectiveness of adding DN to a SE program. An examination of each patient was initially performed prior to intervention, in order to assess common functional limitations, strength deficits, upper extremity use limitations, and to rule out serious neurovascular pathology that might require referral to another medical specialist based upon findings. These examinations were performed before the retrospective review of subject charts for inclusion in this case series.

EXAMINATION

Examination took place at baseline, and upon completion of the therapy intervention period. The number of treatment sessions and duration of treatment depended on each patient's response to the intervention. The number of treatment sessions ranged from four to eight. Treatment was not rendered > eight weeks due to maximal measureable improvement being attained by each patient during that time frame.

Posture and upper extremity active range of motion (AROM) was assessed in standing and sitting and compared bilaterally. Posture assessment included observation of cervical and thoracic curvature and head positioning at rest, scapular positioning, and, scapulothoracic kinematics with AROM in abduction and flexion. Physical examination of each of the patients revealed an exaggerated flexed position of the mid to lower cervical spine and exaggerated extension of the upper cervical spine. AROM of the involved upper extremity in all eight patients showed a “painful arc” sign ranging between 70 to 125 degrees of shoulder abduction, though AROM was normal in all eight patients. No other postural abnormalities were noted.

Bilateral upper extremity (BUE) strength was assessed via manual muscle testing. Global bilateral UE MMT of each of the eight patients was normal (5/5) except for abduction and external rotation, which was found to range from 3+/5 to 4/5 for abduction, and 3+/5 to 4-/5 for external rotation in each of the patients. Pain was reported by each of the patients with MMT in combined ABD and ER.

An upper quarter neurological examination was performed to screen each patient for symptoms of spinal origin. This included dermatomal, myotomal, and deep tendon reflex (DTRs) examination. Dermatomal testing assessed light touch sensory palpation to the upper extremities. Myotomal testing was assessed via MMT of the upper extremities. DTRs were assessed via testing of the C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots in bilaterally and were found to be normal in all patients. Radiculopathy testing included Spurling's for radiculopathy (SP = .95, SN = .93, + LR = 18.6), Centralization for discogenic origin (SP = .94, SN = .40, + LR- 6.7), and Passive Accessory Intervertebral Movement (PAIVM) palpation for zygaphophyseal joint pain syndromes (SP = .81, SN = .94, + LR = 4.9)65. There were no neurovascular or cervical syndrome abnormalities noted.

Special testing included tests for determining shoulder pain origin as proposed in a systematic review by Biederwolf.66 Biederwolf suggested that using the internal rotation manual muscle test (IRMMT) and external rotation manual muscle test (ERMMT) at 90 degrees abduction and 80 degrees external rotation can help determine if the shoulder pain origin is of RTC, intra-articular, or extra-articular origin. Special tests for ruling in/out a partial rotator cuff tear (PRTC) followed a recommended shoulder special test algorithm for clinical diagnostic accuracy. PRTC tear of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor were ruled out via the IRMMT < ERMMT and a negative External Rotation Lag Sign (SP = .98, SN = .69-.98, + LR = 15.5- 34.5) and negative Hornblower's Sign (SP = .93, SN = 1.0, + LR = 14.29). Subscapulis tears were ruled out with a negative internal rotation lag sign (SP = .96, SN = .97, + LR = 24.3).

Subacromial impingement syndrome (SAIS) was assessed via the Biederwolf cluster as follows: IRMMT > ERMMT, 1) Painful Arc Sign, 2) Hawkins-Kennedy Test, and 3) Infraspinatus MMT. If all of three of these tests are (+), there is a +LR = 5.03 and a post-test probability (PTP) = 95% (91% if 2/3 are positive). According to Park et al, the Painful Arc Sign is the most sensitive (73.5%) and the infraspinatus MMT was the most specific (90.1%).67 Internal impingement was ruled out with a (-) ERMMT > IRMMT and (-) Posterior Impingement Sign according to Biederwolf. If both of these tests are (+), there is a PTP nearing 100%, and if both are (-), there is a 2.5% chance of having internal impingement.

Labral pathology special testing lacks high quality clinical test clusters according to Hegedus et al, and according to Jones et al, thus superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) specific physical examination results cannot be used as the sole basis for a SLAP lesion diagnosis.68,69 Given this information, a newer combination of individual tests per Biederwolf was used to rule out SLAP pathology, and this combination included a (-) Biceps Load I Test (SP = .97, SN = .90, + LR = 30), and a (-) Biceps Load II Test (SP = .97, SN = .90, + LR = 30). According to Biederwolf, the psychometric properties of long head of the biceps (LHB) testing is not clinically useful, hence the author used palpation of the LHB to determine pain in this region.

Partial RTC tears, subscapular tears, internal impingement, and SLAP tears were ruled out based on the examination results. A few of the patients were (+) for SAIS and all reported significant tenderness to palpation in the proximal biceps tendon region in the anterior shoulder. It was determined from the examination that the origin of all eight of the patients’ non-specific shoulder pain (NSSP), likely had a RTC (supraspinatus and/ or Infraspinatus/ Teres Minor) tendinopathy component based upon examination synthesis.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION 2

Based upon examination findings, all eight patients were deemed appropriate to receive the intervention described in the “Intervention” section of the case series. There were no contraindications that would preclude any of the eight patients from receiving DN with electrical stimulation and SE. All patients reported no previous limitations in sleep, lifting/ reaching, or general self-care function prior to the onset of their shoulder pain. All eight patients had ongoing shoulder pain affecting their daily activity tolerance and sought long-term pain relief, which they had not received with prior treatment. Progressive shoulder pain coupled with negative contraindications for DN intervention made the patients appropriate for DN to be performed.

OUTCOME MEASURES

The outcome measures used in this case series were the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the Quick DASH (QD), and are reported in Table 1 and Table 1a. The VAS is a 100 mm scale where the patient marked a line at the area most closely associated with their respective pain levels. At baseline, the mean VAS for “best, current, and worst” level scores was 22.5, 28.36, and 68.88 (out of 100) respectively. The VAS has moderate to good reliability (correlation coefficient 0.60-0.77)70 to detect disability and high reliability for pain (correlation coefficient 0.76-0.84).71 The minimal clinical significant change has been reported to be 11 points (mm) on a 100 point (mm) scale.70

Table 1.

Outcome Measure Scores at Baseline and Upon Completion of Treatment

| Outcome | Subject | Subject | Subject | Subject | Subject | Subject | Subject | Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| QD Initial | 68.18 | 90.0 | 25 | 28.36 | 21.15 | 50 | 18 | 43.09 |

| QD Final | 34.09 | 47.72 | 15.90 | 0 | 0 | 4.50 | 0 | 26.09 |

| QD Follow‐Up | 0 | 34.1 | 15.90 | 0 | 0 | 6.81 | 2.27 | 18.20 |

| VAS (mm) Initial: | ||||||||

| Best | 81 | 43 | 0 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Current | 81 | 72 | 11 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| Worst | 100 | 90 | 43 | 68 | 62 | 61 | 54 | 73 |

| VAS (mm) Final: | ||||||||

| Best | 11 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Current | 22 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Worst | 44 | 10 | 32 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| VAS (mm) Follow‐up: | ||||||||

| Best | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Current | 0 | 21 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Worst | 0 | 48 | 27 | 7 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 40 |

QD = Quick DASH

VAS = Visual Analog Scale

Table 1a.

Outcome Measure Means for All Subjects

| Outcome Measure | Mean for 8 Subjects |

|---|---|

| QD Initial | 43.09 |

| QD Final | 16.04 |

| QD Follow‐Up | 6.59 |

| VAS (mm) Initial: | |

| Best | 22.5 |

| Current | 28.36 |

| Worst | 68.88 |

| VAS (mm) Final: | |

| Best | 2.36 |

| Current | 5 |

| Worst | 13.25 |

| VAS (mm) Follow‐UP: | |

| Best | 0.36 |

| Current | 4.88 |

| Worst | 17.88 |

QD = Quick DASH

VAS = Visual Analog Scale

The QD was used to assess functional disability. The higher the recorded score, the greater the disability the patient experienced. The QD is a quick and reliable patient self-report functional outcome tool that can be easily completed and demonstrates good test- retest reliability (0.90) and responsiveness in patients with shoulder pain.72 The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was found to be 8 points, and the minimal detectable change (MDC) was found to be 11 points.72,73 At baseline, the mean QD score for all subjects was 43.09 points.

INTERVENTION

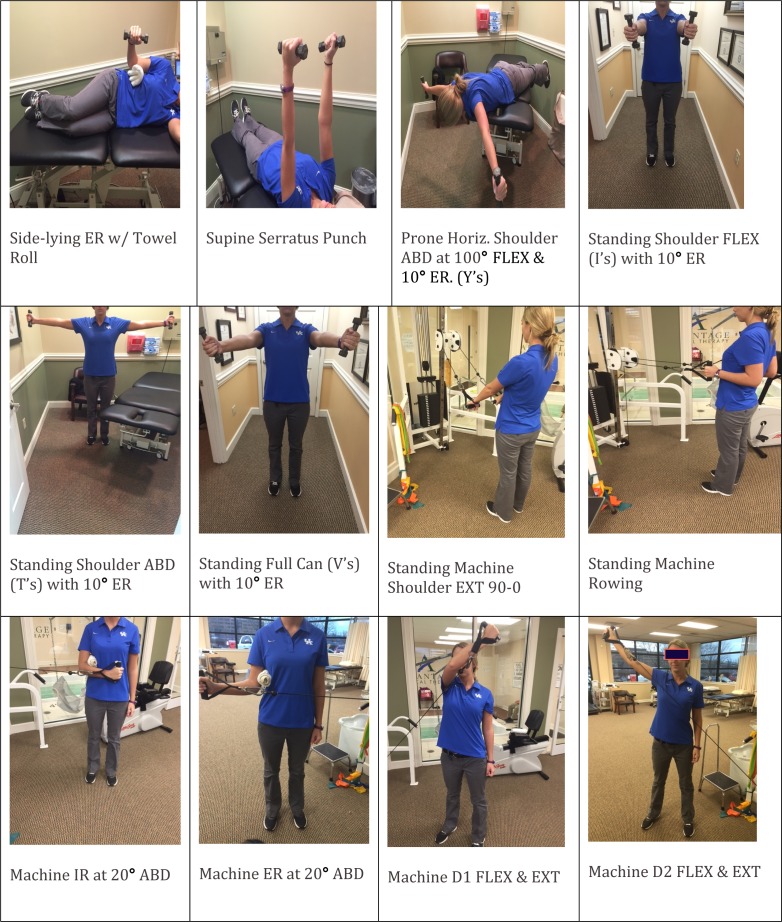

The patients were treated for one to two times per week for up to eight weeks, and no more than sixteen total treatment sessions. Patients were treated with a specific exercise protocol outlined in Appendix A and Table 2, and a five-point DN protocol to the involved shoulder focusing on pain mitigation. The SE protocol was prescribed based on exercises provided in two studies, which suggest evidence-based exercises for improving RTC, deltoid, and scapular strengthening important for optimal shoulder complex kinematics.10,74 Patients performed three sets of 15 repetitions for each exercise, with a weight that was reported by each patient to cause significant fatigue and muscular burning during the last three to four repetitions of each exercise. Resistance was provided in the form of hand weights (dumbbells) and an exercise cable machine.

Table 2.

Strengthening Exercise Protocol

| Variable | Intervention | Dosage | Illustration(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengthening Exercise Activities |

|

3 Sets x 15 Reps For All Interventions. | See Appendix A For Images Of All Exercises Utilized In The Case Series. |

ER = external rotation; ABD = abduction; FLEX = flexion; IR = internal rotation; EXT = extension

During the DN intervention, patients were positioned seated in a chair with the involved upper extremity resting at their side and the hand on the thigh. The following structures were treated: (1) supraspinatus musculo-tendinous junction at the humeral head; (2) supraspinatus anterior and (3) posterior teno-osseous junctions on the greater tuberosity; (4) supraspinatus teno-osseous junction in the muscle belly at the supraspinous fossa; and (5) the deltoid teno-osseous insertion at the deltoid tuberosity. The location of the needles were determined based on the author's DN training and clinical experience with the performance of DN for shoulder pain, and this has become a semi-standardized approach to the application of DN for this condition in the author's private practice. Each patient performed the SE program exactly as listed in Table 2 prior to DN, without variation from one patient to the next.

The needles used in this case series were solid monofilament Seirin J-type sterile needles (Seirin Corp., 1007-1 Sodeshi-Cho, Shimizu-ku, Shizuoka-shi, Shizuoka 424-0036 Japan), 0.30 diameter (DIA) x 50 mm. and 0.25 DIA x 30 mm. Needles were held in the therapist's dominant hand for application and manipulation of the needle within the tissue. Before needle insertion, an application of 70% isopropyl alcohol was performed to the areas and allowed to dry for a least ten-seconds, which reduces the resident micro-flora of the skin by 80-91%.75 All DN interventions were performed according to the Dry Needling Institute (DNI) of the American Academy of Manipulative Therapy (AAMT) Fellowship training program.75 Periosteal pecking to the humerus in various teno-osseous regions was used to attempt to elicit pain relief at the RTC and deltoid attachments throughout the shoulder complex. The electrical stimulation unit used to apply current to the needles was an AWQ-104L digital electro-acupunctoscope, four-channel, eight-lead device (Lahasa OMS, 230 Libbey Parkway, Weymouth, MA 02189). The use of electrical stimulation applied to the needles was performed according to the following parameters outlined by the DNI:75 2 Hz, 250 microseconds, running continuously for twenty minutes in the form of an asymmetric biphasic square wave at an intensity described by the patients as “mild to moderate”. Call bells were left with each patient receiving DN.

Needle insertion points are described in Figure 1 and shown in Figure 2. Manual needle manipulation was utilized after needle insertion, including periosteal pecking and clockwise needle winding. After 10 “periosteal pecks” at bony attachments, the needles were wound clockwise to attain needle grasp between the needle and soft tissue, and left in-situ for 20 minutes.

Figure 1.

Legend (DN Placement).

OUTCOMES

The demographic characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 3. All patients subjectively reported improvements in sleep. The efficacy of DN was assessed by pain response(s), MMT improvement, disability level as reported by the QD, and through subjective reports of improvement in the patient's general daily activity and sleep tolerance. At baseline and upon completion of the intervention, pain and disability were assessed via the VAS and QD outcome measures. Strength of the abductors and external rotators in all eight patients improved to 5/5. The results of these outcome measures are shown in Table 1. Means of the outcome measure scores were used to measure the overall improvement in pain and disability levels, as this gives a general representation of improvement between the eight patients. Each patient met the MCID and MDC for the QD as shown in Table 1. The final QD scores upon completion of the intervention ranged from 0 to 47.72 points versus the initial range of 18 to 90.9 points. The mean improvement between the eight patients demonstrated a mean improvement from 43.09 at baseline to 16.04 at completion of treatment, which is well above the MDC/ MDIC indicating clinically meaningful improvement. At long term follow up, obtained by calling the patients during preparation of the case series (average of 8.75 months after completion of the treatment sessions); the QD average score was 6.59.

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Chronic RTC Tendinopathy.

| Subject | Age (years) | Sex | Time Since Onset (days) | Number of Treatment Sessions Attended Weeks 1-4 | Number of Treatment Sessions Attended Weeks 5-8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63 | M | > 90 days | 6 | 0 |

| 2 | 59 | F | > 90 days | 9 | 6 |

| 3 | 73 | M | > 90 days | 8 | 2 |

| 4 | 29 | M | > 90 days | 3 | 0 |

| 5 | 63 | M | > 90 days | 6 | 1 |

| 6 | 78 | F | > 90 days | 7 | 1 |

| 7 | 39 | M | > 90 days | 7 | 2 |

| 8 | 41 | M | > 90 days | 5 | 2 |

| Average | 55.62 | 9.75 | 1.75 |

The VAS scores were broken down into reported best (VASB), current (VASC), and worst (VASW) levels. Individual VAS ranges were as follows: VASB at baseline, scores ranged from 0 mm to 81 mm and improved to a range of 0 mm to 11 mm at completion of treatment. The VASC ranged from 0 mm to 81 mm and improved to 0 mm to 22 mm upon completion. The VASW scores at baseline ranged from 43 mm to 100 mm and improved to 0 mm to 44 mm upon completion. Means were then calculated to average the eight patient's raw scores for ease of interpretation. The mean VASB score improved from 22.5 mm to 2.36 mm (at completion of treatment). The mean VASC improved from 28.36 mm to 5.0 mm. The mean VASW improved from 68.88 mm to 13.255 mm. At follow up, the mean VASB was 0.36 mm, the mean VASC was 4.888 mm, and the mean VASW was 17.88 mm. All eight patients verbally reported subjective reports of improved sleep, significantly less pain with activities such as grabbing a gallon of milk form the refrigerator, and general improved tolerance to daily activities such as self care/ dressing activities upon completion of treatment, and at the follow-up. Sleep, lifting/ reaching, and general self-care activity limitation was noted as limited prior to initiation of treatment. At the long-term follow up, there were no significant reports of functional limitations reported by any of the eight patients.

| Needle Number | Location |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5 fingerbreadths medial to the medial acromial border angled inferior and slightly laterally. |

| 2 | Anterior “eye” dimple on the greater tuberosity (found by ABD the shoulder to 90 degrees). |

| 3 | Posterior “eye” dimple on the greater tuberosity (found by ABD the shoulder to 90 degrees. |

| 4 | 1 fingerbreadth superior to the midpoint scapular spine angled inferior and posterior. |

| 5 | Deltoid tuberosity attachment on the Humerus. |

DISCUSSION

Clinical results were positive, indicating improvements in pain and disability per the outcome measures used in this retrospective case series. Patient reports of improved sleep, reaching/ lifting ability, and general self-care activity tolerance was also reported at follow up. All patients demonstrated improvements strength, which allowed them to return to independent exercise activities without limitation from shoulder pain, where a lack of ability to exercise was a common report prior to intervention.

Justification for DN to tendinous junctions, was supported by the following concepts: poor tendon vascularization, vessel anastomosis at the tendon-bone, and grafted tendons becoming histologically identical to the original tendon.63 DN techniques such as needle winding may have a local and/ or remote therapeutic effect based on mechanical coupling of connective tissue and the needle, thereby causing a “downstream” pain modulating effect (from the central nervous system to the periphery) on the generation of a mechanical signal caused by needle grasp pulling.75 These downstream effects may include cell secretion, modification of extracellular matrix, enlargement and propagation of the pain signal along connective tissue planes, and afferent input modulation by changes in the connective milieu.76–79 Considering the idea that the supraspinatus has a specific devascularized region, and the vascular supply to tendons has been demonstrated to arise from multiple structures, implications for DN to the tendinous regions of RTC structures appears to be a legitimate area for further investigation63

It should be noted that studies comparing the use of DN with and without electrical stimulation should be performed in the future, as there are no current studies examining DN alone vs. DN with electrical stimulation in the treatment of chronic RTC tendinopathy. There is a good deal of evidence for the use of electrical “acupuncture” in the literature, but minimal evidence for DN alone without the use of electrical stimulation, hence, the author's clinical experience determined the use of electrical stimulation to be an effective adjunct to dry needling. There is also a lack of quality evidence to support specific exercise protocol for the rehabilitation of this condition, so the use of an evidenced-based exercise protocol is necessary to guide Physical Therapists in the rehabilitative process for this condition.

There are limitations to case series such as this. There was a small sample size (n=8). This is an inherent limitation to a case series, though results are more clinically meaningful than a single case report based on having more patients in the series. Given the lack of randomization and no specific inclusion or exclusion criterion, only descriptive outcomes can be reported, and statistical analysis cannot be inferred or provided, thus the level of evidence remains low. The small sample size also makes generalization of the intervention difficult. Also, all eight patients performed SE that may have contributed to the overall positive outcomes, which makes it difficult to determine how much of the improvements were specifically attributable to DN with electrical stimulation, and how much was attributable to the exercise program prescribed. The clinical results were positive, indicating the selected intervention shows promise as a treatment strategy for chronic RTC tendinopathy. Larger randomized control studies looking at DN interventions need to be performed in order to fully assess the effectiveness of DN as an intervention strategy for chronic RTC tendinopathy. Further research is recommended in order to determine if DN with or without electrical stimulation and SE's is clinically beneficial for RTC tendinopathy. There is a fair amount of evidence in support of thrust manipulation to the cervical spine, thoracic spine, and ribs for shoulder pain, and this may be another area of research from a manual therapy approach to include with DN.80–89 Another area of further research should also compare the use of DN with electrical stimulation versus DN alone.

CONCLUSIONS

SE and DN were tolerated well by the patients, demonstrating improvements in pain and function, without significant adverse effects. Given the clinically meaningful reduction in pain and improvements in reported function, the addition of DN to SE for NSSP etiologies shows promise. Future higher-level research is needed to fully explore the effectiveness of DN for chronic RTC tendinopathies when compared to traditional interventions.

Appendix A

Images of SE activities

REFERENCES

- 1.Dinnes J Loveman E McIntyre L Waugh N. The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Tech Assess (Winchester, England). 2003;7(29):iii, 1-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meislin RJ Sperling JW Stitik TP. Persistent shoulder pain: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2005;34(12 Suppl):5-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magarey ME Jones MA Cook CE Hayes MG. Does physiotherapy diagnosis of shoulder pathology compare to arthroscopic findings? Br J Sports Med. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Littlewood C Ashton J Chance-Larsen K May S Sturrock B. Exercise for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(2):101-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunning J Butts R Mourad F Young I Flannagan S Perreault T. Dry needling: a literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines. Phys Ther Rev. 2014;19(4):252-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenzie TA Herrington L Horlsey I Cools A. An evidence-based review of current perceptions with regard to the subacromial space in shoulder impingement syndromes: Is it important and what influences it? Clin Biomech. 2015;30(7):641-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desjardins-Charbonneau A Roy JS Dionne CE Fremont P MacDermid JC Desmeules F. The efficacy of manual therapy for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(5):330-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanratty CE McVeigh JG Kerr DP, et al. The Effectiveness of Physiotherapy Exercises in Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthr Rheum. 2012;42(3):297-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley MJ McClure PW Leggin BG. Frozen shoulder: evidence and a proposed model guiding rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(2):135-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escamilla R Yamashiro K Paulos L Andrews J. Shoulder Muscle Activity and Function in Common Shoulder Rehabilitation Exercises. Sports Med. 2009;39(8):663-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavkovich R. Effectiveness of dry needling, stretching, and strengthening to reduce pain and improve function in subjects with chronic lateral hip and thigh pain: A retrospective case series. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(4):540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rha DW Park GY Kim YK Kim MT Lee SC. Comparison of the therapeutic effects of ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma injection and dry needling in rotator cuff disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(2):113-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldry P. Superficial Dry Needling at Myofascial Trigger Point Sites. J Musculoskel Pain. 1995;3(3):117-126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldry P. Superficial versus deep dry needling. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2002;20(2-3):78-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bubnov RV. The use of trigger point “dry” needling under ultrasound guidance for the treatment of myofascial pain (technological innovation and literature review). Likars’ka sprava / Ministerstvo okhorony zdorov’ia Ukrainy. 2010. (5-6):56-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cagnie B Dewitte V Barbe T Timmermans F Delrue N Meeus M. Physiologic Effects of Dry Needling. Current Science Inc. 2013;17(8):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J-T Chung K-C Hou C-R Kuan T-S Chen S-M Hong C-Z. Inhibitory Effect of Dry Needling on the Spontaneous Electrical Activity Recorded from Myofascial Trigger Spots of Rabbit Skeletal Muscle. Am J Physical Med & Rehabil. 2001;80(10):729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou L-W Kao M-J Lin J-G. Probable Mechanisms of Needling Therapies for Myofascial Pain Control. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : eCAM. 2012;2012:705327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu J. Does EMG (dry needling) reduce myofascial pain symptoms due to cervical nerve root irritation? Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;37(5):259-272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotchett MP Landorf KB Munteanu SE. Effectiveness of dry needling and injections of myofascial trigger points associated with plantar heel pain: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3:18-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotchett MP Landorf KB Munteanu SE Raspovic A. Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for plantar heel pain: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4:5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings TM White AR. Needling therapies in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: A systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(7):986-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiLorenzo L Traballesi M Morelli D, et al. Hemiparetic Shoulder Pain Syndrome Treated with Deep Dry Needling During Early Rehabilitation: A Prospective, Open-Label, Randomized Investigation. J Musculoskel Pain. 2004;12(2):25-34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dommerholt J. Dry needling — peripheral and central considerations. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(4):223-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dommerholt J Moral OMd Gröbli C. Trigger Point Dry Needling. J Man Manip Ther. 2006;14(4):70E-87E. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards J Knowles N. Superficial dry needling and active stretching in the treatment of myofascial pain – a randomised controlled trial. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2003;21(3):80-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez-Carnero J La Touche R Ortega-Santiago R, et al. Short-term effects of dry needling of active myofascial trigger points in the masseter muscle in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24(1):106-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ga H Choi JH Park CH Yoon HJ. Dry needling of trigger points with and without paraspinal needling in myofascial pain syndromes in elderly patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(6):617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ga H Koh HJ Choi JH Kim CH. Intramuscular and nerve root stimulation vs lidocaine injection to trigger points in myofascial pain syndrome. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(5):374-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ge HY Arendt-Nielsen L. Latent myofascial trigger points. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(5):386-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong C-Z. Trigger point injectiosn: Dry needling vs. lidocaine injection. Am J Phys Med & Rehabil. 1992;71(4):251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong C-Z. Lidocaine verst dry needling to myofacscial trigger points: The importance of the local twitch response. Am J Phys Med & Rehabil. 1994;73(4):256-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh Y-L Chou L-W Joe Y-S Hong C-Z. Spinal Cord Mechanism Involving the Remote Effects of Dry Needling on the Irritability of Myofascial Trigger Spots in Rabbit Skeletal Muscle. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(7):1098-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh Y-L Kao M-J Kuan T-S Chen S-M Chen J-T Hong C-Z. Dry Needling to a Key Myofascial Trigger Point May Reduce the Irritability of Satellite MTrPs. Am J Phys Med & Rehabil. 2007;86(5):397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang YT Lin SY Neoh CA Wang KY Jean YH Shi HY. Dry needling for myofascial pain: prognostic factors. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17(8):755-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huguenin L Brukner PD McCrory P Smith P Wajswelner H Bennell K. Effect of dry needling of gluteal muscles on straight leg raise: a randomised placebo controlled, double blind trial. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(2):84-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilbuldu E Cakmak A Disci R Aydin R. Comparison of laser dry needling, and placebo laser treatments in myofascial pain syndrome. Photomedicine and laser surgery. 2004;22(4):306-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irnich D Behrens N Gleditsch JM, et al. Immediate effects of dry needling and acupuncture at distant points in chronic neck pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial. PAIN. 2002;99(1–2):83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jimbo S Atsuta Y Kobayashi T Matsuno T. Effects of dry needling at tender points for neck pain (Japanese: katakori): near-infrared spectroscopy for monitoring muscular oxygenation of the trapezius. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13(2):101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalichman L Vulfsons S. Dry Needling in the Management of Musculoskeletal Pain. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(5):640-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamanli A Kaya A Ardicoglu O Ozgocmen S Zengin FO Bayık Y. Comparison of lidocaine injection, botulinum toxin injection, and dry needling to trigger points in myofascial pain syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25(8):604-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kietrys DM Palombaro KM Azzaretto E, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for upper-quarter myofascial pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(9):620-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kietrys DM Palombaro KM Azzaretto E, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for upper-quarter myofascial pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2013;43(9):620-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewit K. The needle effect in the relief of myofascial pain. PAIN. 1979;6(1):83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu L Huang QM Liu QG, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for myofascial trigger points associated with neck and shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(5):944-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McMillan AS Nolan A Kelly PJ. The efficacy of dry needling and procaine in the treatment of myofascial pain in the jaw muscles. J Orofac Pain. 1997;11(4):307-314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mejuto-Vazquez MJ Salom-Moreno J Ortega-Santiago R Truyols-Dominguez S Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C. Short-term changes in neck pain, widespread pressure pain sensitivity, and cervical range of motion after the application of trigger point dry needling in patients with acute mechanical neck pain: A randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(4):252-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moral OMd. Dry Needling Treatments for Myofascial Trigger Points. J Musculoskel Pain. 2010;18(4):411-416. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osborne NJ Gatt IT. Management of shoulder injuries using dry needling in elite volleyball players. J Br Med Acupunct Soc. 2010;28(1):42-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pavkovich R. The use of dry needling for a subject with chronic lateral hip and thigh pain: A case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(2):246-255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pavkovich R. The use of dry needling for a subject with acute onset neck pain: A case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(1):104-113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pérez-Palomares S Oliván-Blázquez B Magallón-Botaya R, et al. Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Versus Dry Needling: Effectiveness in the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. J Musculoskel Pain. 2010;18(1):23-30. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rha D-w Park G-Y Kim Y-K Kim MT Lee SC. Comparison of the therapeutic effects of ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma injection and dry needling in rotator cuff disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(2):113-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tekin L Akarsu S Durmuş O Çakar E Dinçer Ü; Kıralp M. The effect of dry needling in the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(3):309-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tough EA White AR. Effectiveness of acupuncture/dry needling for myofascial trigger point pain. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2011;16(2):147-154. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tough EA White AR Cummings TM Richards SH Campbell JL. Acupuncture and dry needling in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai C-T Hsieh L-F Kuan T-S Kao M-J Chou L-W Hong C-Z. Remote Effects of Dry Needling on the Irritability of the Myofascial Trigger Point in the Upper Trapezius Muscle. American J Phys Med & Rehabil. 2010;89(2):133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venancio Rde A Alencar FG Zamperini C. Different substances and dry-needling injections in patients with myofascial pain and headaches. J Craniomandib Pract. 2008;26(2):96-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Venancio Rde A Alencar FG Jr., Zamperini C. Botulinum toxin, lidocaine, and dry-needling injections in patients with myofascial pain and headaches. J Craniomandib Pract. 2009;27(1):46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vulfsons S Ratmansky M Kalichman L. Trigger point needling: techniques and outcome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(5):407-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang F Audette J. Electrophysiologic chariacterisitics of the local twitch response in subjects with active myofascial pain of the neck compared with a control group with latent trigger points. Am J Phys Med & Rehabil. 2000;79(2):203. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ziaeifar M Arab AM Karimi N Nourbakhsh MR. The effect of dry needling on pain, pressure pain threshold and disability in patients with a myofascial trigger point in the upper trapezius muscle. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2014;18(2):298-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fenwick SA Hazleman BL Riley GP. The vasculature and its role in the damaged and healing tendon. Arthritis Research. 2002;4(4):252-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunning J Butts R Mourad F Young I Flannagan S Perreault T. Dry needling: a literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines. Phys Ther Rev. 2014;19(4):252-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cook C Hegedus E. Diagnostic utility of clinical tests for spinal dysfunction. Man Ther. 2009;16(1):21-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biederwolf NE. A proposed evidence-based shoilder special testing examination algorithm: Clinical utility based on a systematic review of the literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(4):427-440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park HB Yokota A Gill HS El Rassi G McFarland EG. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome. JBJS. 2005;87(7):1446-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hegedus EJ Cook C Lewis J Wright A Park J-Y. Combining orthopedic special tests to improve diagnosis of shoulder pathology. Phys Ther in Sport. 2015;16(2):87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones GL Galluch DB. Clinical Assessment of Superior Glenoid Labral Lesions: A Systematic Review. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2007;455:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boonstra AM Schiphorst Preuper HR Reneman MF Posthumus JB Stewart RE. Reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale for disability in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. International journal of rehabilitation research. Internationale Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue internationale de recherches de readaptation. 2008;31(2):165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bijur PE Silver W Gallagher EJ. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(12):1153-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mintken PE Glynn P Cleland JA. Psychometric properties of the shortened disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (QuickDASH) and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with shoulder pain. J Should Elbow Surg. 18(6):920-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Polson K Reid D McNair PJ Larmer P. Responsiveness, minimal importance difference and minimal detectable change scores of the shortened disability arm shoulder hand (QuickDASH) questionnaire. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):404-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ellenbecker TS Cools A. Rehabilitation of shoulder impingement syndrome and rotator cuff injuries: an evidence-based review. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):319-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.James Dunning D, MSc Manip. Ther., OCS, MSCP, MAACP (UK), FAAOMPT, MMACP (UK). DN-1: Dry Needling for Craniofacial, Cervicothoracic & Upper Extremity COnditions: an Evidence-Based Approach. Montgomery, AL: Dry Needling Institute of the American Academy of Manipulative Therapy; 2012:256. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Langevin HM Churchill DL Cipolla MJ. Mechanical signaling through connective tissue: a mechanism for the therapeutic effect of acupuncture. The FASEB Journal. 2001;15(12):2275-2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Langevin HM Churchill DL Fox JR Badger GJ Garra BS Krag MH. Biomechanical response to acupuncture needling in humans. J Appl Phisiol. 2001;91(6):2471-2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langevin HM Bouffard NA Badger GJ Iatridis JC Howe AK. Dynamic fibroblast cytoskeletal response to subcutaneous tissue stretch ex vivo and in vivo. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol. 2005;288(3):C747-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Langevin HM Bouffard NA Badger GJ Churchill DL Howe AK. Subcutaneous tissue fibroblast cytoskeletal remodeling induced by acupuncture: Evidence for a mechanotransduction-based mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207(3):767-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bergman GJ Winters JC Groenier KH, et al. Manipulative therapy in addition to usual medical care for patients with shoulder dysfunction and pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):432-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Boyle JJ. Is the pain and dysfunction of shoulder impingement lesion really second rib syndrome in disguiseϿ. Two case reports. Man Ther. 1999;4(1):44-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boyles RE Ritland BM Miracle BM, et al. The short-term effects of thoracic spine thrust manipulation on patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Man Ther. 2009;14(4):375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strunce JB Walker MJ Boyles RE Young BA. The immediate effects of thoracic spine and rib manipulation on subjects with primary complaints of shoulder pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):230-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aoyagi M Mani R Jayamoorthy J Tumilty S. Determining the level of evidence for the effectiveness of spinal manipulation in upper limb pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther. 2015;20(4):515-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wassinger CA Rich D Cameron N, et al. Cervical & thoracic manipulations: Acute effects upon pain pressure threshold and self-reported pain in experimentally induced shoulder pain. Man Ther. 2016;21:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coronado RA Bialosky JE Bishop MD, et al. The comparative effects of spinal and peripheral thrust manipulation and exercise on pain sensitivity and the relation to clinical outcome: a mechanistic trial using a shoulder pain model. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(4):252-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muth S Barbe MF Lauer R McClure PW. The effects of thoracic spine manipulation in subjects with signs of rotator cuff tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(12):1005-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peek AL Miller C Heneghan NR. Thoracic manual therapy in the management of non-specific shoulder pain: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther. 2015;23(4):176-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mintken PE Cleland JA Carpenter KJ Bieniek ML Keirns M Whitman JM. Some factors predict successful short-term outcomes in individuals with shoulder pain receiving cervicothoracic manipulation: a single-arm trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90(1):26-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]