Abstract

Background

In the setting of chronic kidney disease (CKD), altered extra-renal urate handling may be necessary to regulate plasma uric acid. The Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis (Nigam S. What do drug transporters really do? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015; 14: 29–44) suggests that multispecific solute carrier (SLC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporters in different tissues are part of an inter-organ communication system that maintains levels of urate and other metabolites after organ injury.

Methods

Data from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC; n = 3598) were used to study associations between serum uric acid and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the following uric acid transporters: ABCG2 (BRCP), SLC22A6 (OAT1), SLC22A8 (OAT3), SLC22A10 (OAT5), SLC22A11 (OAT4), SLC22A12 (URAT1), SLC22A13 (OAT10), SLC17A1-A3 (NPTs), SLC2A9 (GLUT9), ABCC2 (MRP2) and ABCC4 (MRP4). Regression models, controlling for principal components age, gender and renal function, were run separately for those of European (EA) and African ancestry (AA), and P-values corrected for multiple comparisons. A twin cohort with participants of EA and normal renal function was used for comparison.

Results

Among those of EA in CRIC, statistically significant signals were observed for SNPs in ABCG2 (rs4148157; beta-coefficient = 0.68; P = 4.78E-13) and SNPs in SLC2A9 (rs13125646; beta-coefficient = −0.30; P = 1.06E-5). Among those of AA, the strongest (but not statistically significant) signals were observed for SNPs in SLC2A9, followed by SNPs in ABCG2. In the twin study (normal renal function), only SNPs in SLC2A9 were significant (rs4481233; beta-coefficient=−0.45; P = 7.0E-6). In CRIC, weaker associations were also found for SLC17A3 (NPT4) and gender-specific associations found for SLC22A8 (OAT3), SLC22A11 (OAT4), and ABCC4 (MRP4).

Conclusions

In patients of EA with CKD (CRIC cohort), we found striking associations between uric acid and SNPs on ABCG2, a key transporter of uric acid by intestine. Compared with ABCG2, SLC2A9 played a much less significant role in this subset of patients with CKD. SNPs in other SLC (e.g. SLC22A8 or OAT3) and ABC (e.g. ABCC4 or MRP4) genes appear to make a weak gender-dependent contribution to uric acid homeostasis in CKD. As renal urate transport is affected in the setting of declining kidney function, extra-renal ABCG2 appears to play a compensatory role—a notion consistent with animal studies and the Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis. Overall, the data indicate how different urate transporters become more or less important depending on renal function, ethnicity and gender. Therapies focused on enhancing ABCG2 urate handling may be helpful in the setting of CKD and hyperuricemia.

Keywords: ABCG2, CKD, gastrointestinal transport, sex interaction, SLC2A9

Introduction

Alterations of serum uric acid are a common metabolic abnormality associated with diseases such as gout, kidney stones, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD). A number of studies, both clinical and basic, have implicated solute carrier (SLC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in uric acid handling [1–4]. Many of these transporters are also considered ‘drug’ transporters. Putative uric acid transporters include: ABCG2 (BCRP), SLC2A9 (GLUT9), SLC22A12 (URAT1; originally identified as Rst in mice), SLC17A1-3 (NPTs), SLC22A6 (OAT1), SLC22A8 (OAT3) and SLC22A11 (OAT4) [1–17].

While in vitro transport studies and murine knockouts may serve as a guide, the physiology in humans may be substantially different [18]. Furthermore, little is known about coordination between uric acid transporters, including the potential role of non-renal transporters, or the relative importance of various transporters in specific patient populations. Indeed, much of the uric acid is excreted by the kidney [1–4], yet uric acid homeostasis in the setting of the failing kidney has not been extensively studied. While SLC2A9 has been identified as the main uric acid transporter in general cohorts, the role of SLC2A9 and other SLC and ABC transporters in patients with CKD has not been studied. The Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis proposes that multispecific SLC and ABC ‘drug’ transporters in different tissues are part of an inter-organ and inter-organismal communication network that maintains levels of uric acid, metabolites and signaling molecules in the setting of acute or chronic injury to organs such as the kidney, or other organs [3]. Thus, in the setting of CKD, where uric acid handling by renal urate transporters can be compromised, extra-renal urate transporters, such as ABCG2 in the intestine, may play a more prominent role in uric acid homeostasis. This notion is supported by animal studies [5].

This study explored associations between serum uric acid and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a number of SLC and ABC genes (proven to regulate uric acid in vitro or in vivo in human and/or mouse) in a well-characterized cohort of 3591 patients with CKD from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study [19]. A twin study (n = 481) with participants with hypertension but normal renal function was used as comparison [20, 21]. The African American Study of Hypertension and Kidney Disease (AASK; n = 508), a cohort with early renal insufficiency, was used as secondary sample for African Americans [22]. Our results support the view that, as renal function declines, extra-renal ABCG2, most likely in the intestine, compensates to maintain uric acid homeostasis. The results are consistent with animal models of renal decline [5] and support the relevance of the Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis for understanding metabolic disease in humans [3].

Materials and methods

CRIC study cohort

The CRIC study was established by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) to examine risk factors for the progression of CKD and cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD [19]. Data were obtained through authorized access to dbGaP and the NIDDK data repository. Seven clinical centers recruited adults with CKD based on age-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2) and included women (46%), Caucasians (45%), non-Hispanic Black (46%) and Hispanic (5%); 47% also had diabetes. Participants (N = 3591 with genotype data) were between ages 21 and 74 years, with a median age of 58 years. Blood and urine specimens were collected, and information regarding health behaviors, diet, quality of life and functional status was obtained at baseline. Serum uric acid in mg/dL was determined by standard laboratory procedures (uricase/peroxidase enzymatic method; DAX 96; Bayer Diagnostics, Milan, Italy). Baseline measures included renal function, medications and age [23].

Genetics

Genotyping was carried out using the Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad_v1-0_B platform [19]. Gene regions chosen for this study were selected based on previous genome-wide association study (GWAS) of uric acid transporters, including both in vitro and animal studies. Variants in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05 in European ancestry (EA) and African ancestry (AA) and within 30 kb upstream or downstream of the following genes were investigated: ABCG2, SLC22a12, SLC22A6, SLC22A8, SLC22A13, SLC17A1, SLC17A2, SLC17A3, SLC22A9, ABCC2 and ABCC4. Based on the number of SNPs (980), the significance level used to assess single SNP association after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison was P = 5.10E-5. Population allele frequencies and linkage disequilibrium (LD) were assessed using Haploview (http://www.broadinstitute.org/scientific-community/science/programs/medical-and-population-genetics/haploview/haploview). The strength of association and correlations between SNPs for significant genes were generated using LocusZoom [24]. Correlations were imputed using 1000 Genomes Project, March 2012 (www.1000genomes.org); because of differences in linkage structure, correlations were imputed by EA and AA.

Statistics

Screening/discovery associations

An initial screen for associations between uric acid and SNPs was run with PLINK, an online software program used for genome-wide associations and/or to control genetic associations for population stratification using a multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) analysis [25]. Data were run separately for those of EA and AA and controlled for principal components age, sex, diuretic, allopurinol, eGFR and a diagnosis of diabetes. Based on previous literature suggesting sex specificity with respect to SLC transporters [26–28], the three most significant SNPs from the discovery analysis were also screened for interactions with sex using PLINK. Models were stratified by sex if the interaction term (SNP*SEX) was significant (P ≤ 0.05).

Individual SNPs

The most significant SNPs for CRIC were further analyzed with SAS (V 9.1 SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or STATA (V10, College Station, TX, USA). Multivariate linear regression models were used to determine beta-coefficients and confidence intervals for significant SNPs controlling for population stratification, age, gender, diabetes and eGFR.

Power calculations

Post hoc power calculations, done using G*Power (http://www.gpower.hhu.de/), indicated adequate power to detect relatively small effects in CRIC. Estimates were based on a dominant/recessive genetic model using a two-sided T-test and an alpha level of 5.1 × 10−5 (Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons). Among those of EA (n = 2086), the CRIC study had ∼80% power to detect a 0.35 mg/dL difference in serum uric acid (an estimated small effect size of 0.19, Cohen's D statistic) for SNPs with a MAF of 0.10; among those of AA (n = 1505), there was ∼80% power to detect a 0.45 mg/dL difference in uric acid (small effect size ∼0.25). For rare alleles with a MAF of 0.05, there was ∼80% power to detect a 0.38 mg/dL difference (small effect size ∼0.21) and 0.45 mg/dL difference (small effect size ∼0.25) for EA and AA, respectively.

Twin study

This study population has been described previously [20, 21]. Participants were recruited from the southern California Twin Registry [20]. Additional participants were recruited by newspaper advertisement [21]. The twin cohort included 260 nuclear families (mean size = 2.4, range: 1–9), 60 dizygotic and 161 monozygotic twin pairs. Zygosity was confirmed by microsatellite and SNP markers. For this analysis, individuals of Caucasian (European-American, n = 535) or Hispanic (Mexican-American, n = 81) ancestry/ethnicity were included (N = 616). Ethnicity was based on self-identification and geographic origin of parents and all four grandparents. Age ranged from 14 to 78 years with a median of 39 years. The majority was female (442 females and 174 males).

Genetics

A subset of 481 subjects was genotyped on 592 312 SNPs using the Illumina 610 Quad genotyping array. For each of the 161 monozygotic twin pairs, only one individual was genotyped and the genotype information was used for both twins. As an additional quality control step, unlikely genotypes based on expected inheritance patterns were removed using Merlin's Pedwipe procedure. Imputation was performed using MACH v1.0.16 (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/MACH/) with the phased haplotypes of 60 HapMapII CEU founders as reference data. A total of 2 028 122 high-confidence SNPs in LD (r2≥ 0.3) with original genotyped markers were imputed. There were 1256 SNPs on genes listed above in HWE with MAF ≥ 0.01 that were selected for further analysis.

Statistics

Screening/discovery associations

Genetic background heterogeneity was controlled by MDS using PLINK [25]. Association analysis between SNPs and serum uric acid was done using Merlin v1.1.2 (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/merlin/). Family relatedness and twin status was controlled for using a maximum likelihood estimation test of variance components incorporating a variance-covariance matrix. In addition, age, gender and the first MDS component were included as covariates.

Power calculations

For the twin study, a power calculation using the genetic power calculator for quantitative trait locus (QTL) association in sib-ships showed that we were adequately powered (>85% power) to detect the observed variance explained (H2 = 5.55), assuming an additive genetic model, perfect LD between rs4481233 and the QTL, 230 families and 1256 SNPs tested.

AASK study

Because of limited power for African Americans in CRIC, data from the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) were used to increase the sample size. Here, SNPs most significantly associated with uric acid from CRIC were studied. AASK randomized 1094 African American men and women with early hypertensive nephrosclerosis to one of three classes of anti-hypertensive medications. Details of this study have been published [22]. Approximately 41% of this study cohort was female, with an average age of 54 years and mean eGFR of 47 mL/min/1.73 m2. Baseline serum uric acid was drawn prior to randomization. A subset of this cohort with adequate DNA had a genome-wide scan, using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0. After quality control measures, there were 508 successful samples from which data were provided for this study. Associations between SNPs and uric acid were controlled for baseline diuretic use, age and baseline eGFR.

Results

We first briefly describe the overall approach. The uric acid transporter genes that we focused on have previously been shown to function in uric acid handling by in vitro assays (e.g. microinjected Xenopus oocytes, transfected cells, renal slices), body fluid analysis of knockout mice, on Mendelian conditions affecting uric acid and/or by GWAS. In many cases, the SLC (e.g. SLC2A9) and ABC (e.g. ABCG2) transporters we considered have been validated in several of these kinds of studies and have been recently reviewed [2–4].

The goal was to examine the relative importance of various renal and non-renal urate transporters in the setting of declining renal function. One hypothesis, based on animal physiological data indicating that intestinal ABCG2 transport becomes much more important in the setting of 5/6th nephrectomy [5] was that, in patients with CKD, SNPs in ABCG2 will be more significant. We sought to examine this in CKD and patients with normal renal function, separately analyzing those of EA and AA.

After an initial screening/discovery analysis in PLINK by EA and AA, multivariate regression models were used to estimate adjusted effects for most significant SNPs with confidence intervals. As power was limited for AA, data from AASK were used to augment the sample size. A cohort of twins was used as a comparison in individuals with normal renal function. For each of the genes studied here, the first three SNPs most strongly associated with serum uric acid from initial screening in PLINK are shown in Table 1 for CRIC and Table 2 for the twin data set. Results for individual SNPs are shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Discovery analysisa CRIC (with CKD)

| Gene (CHR) | European ancestry |

African ancestry |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Locationb | A1 | MAF | BETA | P | SNP | Location | A1 | MAF | BETA | P | |

| ABCG2 (4) | rs4148157 | Intronic | A | 0.10 | 0.68 | 4.78E-13a | rs10433946 | Intronic | G | 0.06 | −0.42 | 0.001486 |

| ABCG2 (4) | rs4693924 | Intronic | A | 0.10 | 0.68 | 4.78E-13a | rs4148150 | Intronic | A | 0.06 | −0.39 | 0.001656 |

| ABCG2 (4) | rs2054576 | Intronic | G | 0.10 | 0.68 | 5.08E-13a | rs2231137 | Missense | A | 0.06 | −0.37 | 0.002264 |

| SLC2A9 (4) | rs13125646 | Synonymous | A | 0.22 | −0.30 | 0.0000106a | rs10805346 | Intronic | A | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.0003544 |

| SLC2A9 (4) | rs4481233 | Intronic | A | 0.20 | −0.30 | 0.00002923a | rs3756231 | Intronic | G | 0.11 | −0.33 | 0.0006064 |

| SLC2A9 (4) | rs1014290 | Intronic | G | 0.26 | −0.27 | 0.00003387a | rs3775948 | Intronic | C | 0.33 | −0.22 | 0.0006497 |

| ABCC2 (10) | rs2073337 | Intronic | G | 0.39 | −0.10 | 0.07911 | rs17112266 | Intronic | A | 0.09 | −0.18 | 0.09621 |

| ABCC2 (10) | rs3740074 | Intronic | G | 0.38 | −0.10 | 0.0824 | rs4148399 | Intronic | C | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.1024 |

| ABCC2 (10) | rs2756114 | Intronic | G | 0.39 | −0.10 | 0.08486 | rs8187692 | Missense | A | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.1067 |

| SLC17A3 (6) | rs9348697 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.37 | −0.16 | 0.005524 | rs501220 | Intronic | A | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.01853 |

| SLC17A3 (6) | rs13198474 | 5′-UTR | A | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.03422 | rs17586946 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.07 | −0.23 | 0.05102 |

| SLC17A2 (6) | rs17526722 | Intronic | A | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.03949 | rs670011 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.22 | −0.14 | 0.05353 |

| SLC22A10 (11) | rs1193726 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.01853 | rs557879 | Intronic | G | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.2655 |

| SLC22A10 (11) | rs1790218 | Nonsense | G | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.01892 | rs513338 | Intronic | A | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.2772 |

| SLC22A10 (11) | rs1404608 | 3′-UTR | A | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.01905 | rs549144 | 5′ upstream | C | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.2858 |

| SLC22A8 (11) | rs3809069 | 5′ upstream | G | 0.16 | −0.18 | 0.02066 | rs4149179 | 5′-UTR | A | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.02004 |

| SLC22A8 (11) | rs4963326 | Intronic | A | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.05822 | rs1004836 | Intronic | G | 0.24 | −0.12 | 0.09028 |

| SLC22A8 (11) | rs948979 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06354 | rs4149181 | Intronic | A | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.09549 |

| SLC22A11 (11) | rs7936185 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.43 | −0.15 | 0.009676 | rs17300741 | Intronic | G | 0.36 | −0.11 | 0.08903 |

| SLC22A11 (11) | rs12417589 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.43 | −0.14 | 0.01956 | rs7124676 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.11 | −0.097 | 0.3353 |

| SLC22A11 (11) | rs4930195 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.45 | −0.13 | 0.02977 | rs7104900 | 5′ upstream | G | 0.18 | 0.058 | 0.4635 |

| ABCC4 (13) | rs7981095 | Intronic | T | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.01123 | rs4771912 | Intronic | G | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.004573 |

| ABCC4 (13) | rs4771912 | Intronic | G | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.01861 | rs9516518 | 3′ downstream | G | 0.13 | −0.19 | 0.03153 |

| ABCC4 (13) | rs9524864 | Intronic | A | 0.49 | −0.12 | 0.03875 | rs9561797 | Intronic | G | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.03369 |

| SLC22A13 (3) | rs9874338 | Intronic | C | 0.10 | −0.085 | 0.3899 | rs7636551 | Intronic | G | 0.11 | −0.16 | 0.09025 |

| SLC22A13 (3) | rs4679027 | Intronic | C | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.3919 | rs9827811 | Intronic | A | 0.05 | −0.21 | 0.135 |

| SLC22A13 (3) | rs1979845 | Intronic | A | 0.10 | −0.072 | 0.4618 | rs9874338 | Intronic | C | 0.44 | 0.063 | 0.314 |

| SLC22A6 (11) | rs4149170 | 5′-UTR | A | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.07487 | rs3017670 | Intronic | A | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.2538 |

| SLC22A6 (11) | rs10897312 | Intronic | A | 0.09 | −0.16 | 0.09564 | rs12276943 | Intronic | A | 0.23 | −0.07 | 0.3517 |

| SLC22A6 (11) | rs3017670 | Intronic | A | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.5461 | rs11828160 | 3′ downstream | A | 0.23 | −0.06 | 0.4009 |

| SLC22A12 (11) | rs3802947 | Intron of NRXN2 | A | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.06009 | rs7932437 | 3′ of NRXN2 | G | 0.20 | −0.12 | 0.1493 |

| SLC22A12 (11) | rs3741399 | 3′-UTR of NRXN2 | A | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.06062 | rs11231825 | Synonymous | G | 0.18 | −0.10 | 0.2178 |

| SLC22A12 (11) | rs475688 | Intronic | A | 0.25 | −0.06 | 0.3366 | rs11606370 | Intron of NRXN2 | A | 0.17 | −0.10 | 0.2415 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; CHR, chromosome; A1, minor allele; MAF, minor allele frequency; BETA, beta-coefficient from PLINK regression; P, P-value for beta-coefficient; UTR, untranslated region.

aAdjusted for: population stratification, age, gender, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, diuretic and allopurinol treatment.

bSNP location from dbSNP.

Table 2.

Discovery analysis twin data (no CKD)

| Gene (CHR) | SNP | Locationa | A1 | MAF | BETA | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCG2 (4) | rs2231146 | Intronic | C | 0.015 | −0.681 | 0.029 |

| ABCG2 (4) | rs12641369 | Intronic | A | 0.056 | −0.276 | 0.098 |

| ABCG2 (4) | rs2231137 | Missense | T | 0.056 | −0.276 | 0.098 |

| SLC2A9 (4) | rs4481233 | Intronic | T | 0.199 | −0.447 | 7.01E-06 |

| SLC2A9 (4) | rs13111638 | Intronic | T | 0.2 | −0.414 | 2.16E-05 |

| SLC2A9 (4) | rs6449213 | Intronic | C | 0.2 | −0.414 | 2.16E-05 |

| ABCC2 (10) | rs10509739 | 3′ downstream | T | 0.067 | −0.296 | 0.060 |

| ABCC2 (10) | rs4148396 | Intronic | T | 0.361 | −0.112 | 0.154 |

| ABCC2 (10) | rs2756111 | Intronic | C | 0.058 | 0.227 | 0.160 |

| SLC17A1-17A3 (6) | rs11969868 | Intronic | G | 0.183 | −0.241 | 0.014 |

| SLC17A1-17A3 (6) | rs9461211 | 5′ upstream | A | 0.452 | 0.163 | 0.028 |

| SLC17A1-17A3 (6) | rs2275906 | Synonymous | G | 0.131 | −0.247 | 0.032 |

| SLC22A10 (11) | rs7942667 | Intronic | C | 0.029 | 0.345 | 0.139 |

| SLC22A10 (11) | rs17158018 | Intronic | G | 0.029 | 0.345 | 0.140 |

| SLC22A10 (11) | rs17158022 | Intronic | A | 0.029 | 0.342 | 0.146 |

| SLC22A8 (11) | rs10792369 | 5′ upstream | C | 0.349 | 0.114 | 0.171 |

| SLC22A8 (11) | rs4149181 | Intronic | G | 0.082 | 0.167 | 0.213 |

| SLC22A8 (11) | rs4963326 | Intronic | A | 0.42 | 0.1 | 0.259 |

| SLC22A11 (11) | rs3759053 | 5′ upstream | C | 0.474 | 0.181 | 0.016 |

| SLC22A11 (11) | rs11231813 | 5′ upstream | G | 0.494 | −0.149 | 0.0496 |

| SLC22A11 (11) | rs17300741 | Intronic | T | 0.488 | −0.025 | 0.099 |

| ABCC4 (13) | rs4148499 | Intronic | T | 0.156 | −0.216 | 0.049 |

| ABCC4 (13) | rs12870204 | Intronic | T | 0.39 | −0.135 | 0.087 |

| ABCC4 (13) | rs9524848 | Intronic | G | 0.974 | −0.397 | 0.087 |

| SLC22A13 (3) | rs3805040 | Intronic | G | 0.054 | −0.23 | 0.188 |

| SLC22A13 (3) | rs1979845 | Intronic | T | 0.114 | −0.149 | 0.224 |

| SLC22A13 (3) | rs2236631 | Intronic | T | 0.053 | −0.147 | 0.374 |

| SLC22A6 (11) | rs11828074 | 5′ upstream | T | 0.063 | 0.145 | 0.339 |

| SLC22A6 (11) | rs11568621 | Intronic | A | 0.063 | 0.145 | 0.339 |

| SLC22A6 (11) | rs11568628 | Synonymous | T | 0.373 | 0.031 | 0.691 |

| SLC22A12 (11) | rs476037 | 3′-UTR | A | 0.136 | 0.166 | 0.143 |

| SLC22A12 (11) | rs578829 | 5′ upstream | C | 0.334 | 0.025 | 0.759 |

| SLC22A12 (11) | rs11231825 | Synonymous | T | 0.334 | 0.025 | 0.759 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; CHR, chromosome; A1, minor allele; MAF, minor allele frequency; BETA, beta-coefficient from PLINK regression; P, P-value for beta-coefficient; UTR, untranslated region.

aSNP location from dbSNP.

Table 3.

Most significant SNPs in EA (CRIC)

| Gene | n | Uric acid mg/dL (SD) | Multivariable regressiona |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BETAa | Adjusteda P-value | 95% CIa | |||

| ABCG2 rs4148157 | |||||

| GG | 1627 | 6.99 (1.85) | Reference | ||

| GA/AA | 438 | 7.64 (2.05) | 0.64 | <0.001 | 0.47 to 0.81 |

| SLC2A9 rs13125646 | |||||

| GG | 1211 | 7.21 (1.87) | Reference | ||

| GA | 727 | 7.04 (1.93) | −0.25 | 0.001 | −0.40 to −0.10 |

| AA | 126 | 6.86 (2.08) | −0.51 | 0.001 | −0.81 to −0.22 |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; EA, European ancestry; CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; BETA, beta-coefficient from PLINK regression; CI, confidence interval.

aAdjusted for: population stratification, age, gender, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, diuretic and allopurinol treatment.

CRIC

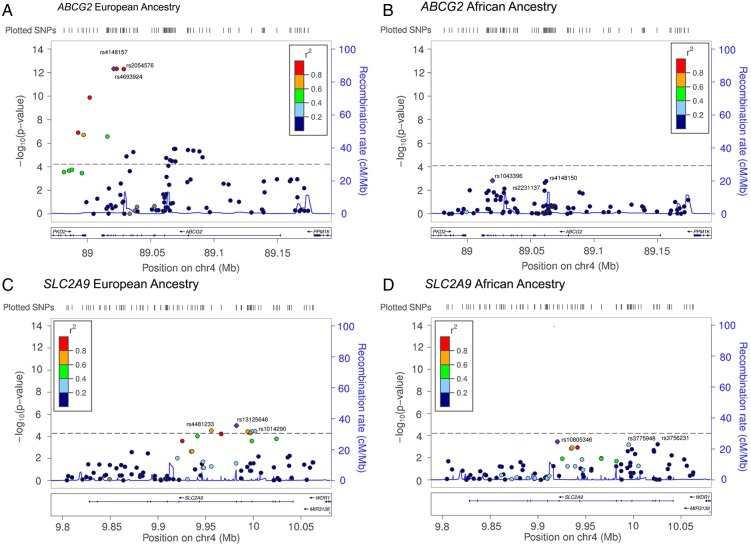

The strength of associations between serum uric acid and SNPs on ABCG2 and SCL2A9 are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Strength of association for ABCG2 and SLC2A9 gene regions. The strength of the associations (−Log10 P-values) between ABCG2 and SLC2A9 SNPs and serum uric acid in the CRIC population stratified by European and African ancestry are shown. The correlation (r2) between the most highly associated SNPs (indicated by a purple diamond) and all other SNPs tested in the region is represented using the color scheme shown in the legend on the upper left corner of each plot. Correlations were estimated in populations from the 1000 Genomes Project (Mar 2012) with European ancestry or African ancestry. (A) ABCG2 SNPs among those of European ancestry. (B) ABCG2 SNPs among those of African ancestry. (C) SLC2A9 SNPs among those of European ancestry. (D) SLC2A9 SNPs among African ancestry. Recombination rates in cM per Mb and Human genome build 19 coordinates (Mb) are also shown. Plots were generated using LocusZoom [24].

European ancestry

Among those of EA, by far the strongest signals were for SNPs in ABCG2. This was followed by SLC2A9—the latter gene being about eight orders of magnitude less significant than ABCG2 (∼E-13 versus ∼E-5). The most significant SNP, ABCG2 rs4148157 (P = 4.78E-13, beta-coefficient = 0.68) had MAF of 0.10 (Table 1). Serum uric acid was 6.99 [standard deviation (SD): 1.85] mg/dL and 7.64 (SD: 2.05) mg/dL by ABCG2 rs4148157 GG and GA/AA genotypes (Table 3; unadjusted P < 0.001, not shown). Multivariable regression estimated an adjusted 0.64 mg/dL increase [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.47 to 0.81] in uric acid by ABCG2 rs4148157 genotypes (GA/AA compared with GG; P < 0.001, Table 3).

Top signals in SLC2A9 were for SNPs with more common allele frequencies (MAF ≥ 0.20); rs13125646 was the most significant SL2A9 SNP (P = 1.06E-5, beta-coefficient = −0.30; Table 1). Serum uric acid was 7.21 (SD: 1.87) mg/dL, 7.04 (SD: 1.93) mg/dL and 6.86 (SD: 2.08) mg/dL by GG, GA and AA genotypes, respectively (Table 3; unadjusted P = 0.001, not shown). In comparison with GG, multivariate regression estimated a 0.25 mg/dL (95% CI: −0.40 to −0.10; P = 0.001) decrease in uric acid with GA and 0.51 mg/dL (95% CI: −0.81 to −0.22; P = 0.001) decrease in uric acid with AA genotypes (Table 3).

SNPs on SLC17A3, SLC22A10, SLC22A8, SLC22A11 and ABCC4 were nominally significant at P ≤ 0.05 (Table 1).

African ancestry

There were no significant SNPs after correction for multiple comparisons among AA (P ≤ 5.10E-5). However, SNPs in SCL2A9 had the strongest signals, followed by SNPs in ABCG2. There was some association at P ≤ 0.05 for SNPs on SLC17A3, SLC22A8 and ABCC4 (Table 1).

Twin study

After correcting for multiple comparisons, only SNPs in SLC2A9 were significantly associated with serum uric acid (most significant rs4481233, P = 7.01E-6; beta-coefficient = −0.45; Table 2). Although of marginal significance, associations with SLC17A1-17A3 (rs11969868, P = 0.014), ABCG2 (rs2231146, P = 0.029) and ABCC4 (rs4148499, P = 0.049) were also observed among the twins. Of note, SLC22A11 (rs3759053, P = 0.016), not observed in CRIC, was also nominally significant (Table 2).

ABCG2 and SLC2A9 associations among AA (CRIC and AASK combined)

As power was limited for those of AA in the CRIC dataset, CRIC data were combined with AASK, a cohort of African Americans with renal insufficiency. Only the most significant SNPs from CRIC (EA or AA) were studied here. If the same SNP was not available, a SNP in linkage disequilibrium was chosen. Results for multivariate regression models adjusted for sex, age, baseline eGFR, diuretic use and study (CRIC or AASK) for are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Most sinificant SNPs in AA (AASK and CRIC)

| n | Uric acid mg/dL (SD) | Multivariable regressiona |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BETAa | Adjusted P-valuea | 95% CIa | |||

| ABCG2 rs4148157 | |||||

| GG | 1863 | 7.87 (1.91) | Reference | ||

| GA/AA | 126 | 8.20 (2.0) | 0.41 | 0.0095 | 0.10 to 0.72 |

| SLC2A9 rs13111638 | |||||

| CC | 1404 | 7.97 (1.93) | Reference | ||

| CT/TT | 502 | 7.65 (1.86) | −0.32 | 0.0004 | −0.49 to −0.14 |

| SLC2A9 rs6449213 | |||||

| AA | 1483 | 7.98 (1.96) | Reference | ||

| AG/GG | 509 | 7.66 (1.78) | −0.33 | 0.0002 | −0.50 to −0.15 |

| SLC2A9 rs4481233 | |||||

| CC | 1649 | 7.94(1.94) | Reference | ||

| CT/TT | 330 | 7.65 (1.80) | −0.23 | 0.023 | −0.43 to −0.033 |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; AA, African ancestry; AASK, African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension; CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; BETA, beta-coefficient from PLINK regression; CI, confidence interval.

aAdjusted for: study population, age, gender, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, diuretic and allopurinol treatment.

ABCG2 rs4148157

Genotype data were available for ABCG2 rs4148157, by far the most significant SNP in CRIC among those of EA. Results were similar in the combined CRIC-AASK data for those of AA. Serum uric acid was higher with GA/AA genotypes in comparison with GG genotypes: 8.20 (SD: 2.0) mg/dL versus 7.87 (SD: 1.91) mg/dL (Table 4; P = 0.063, not shown). Multivariable regression estimated a 0.41 mg/dL (95% CI: 0.10 to 0.72) increase in uric acid with the G minor allele (Table 4; P = 0.0095).

SLC2A9 rs13111638, rs6449213 and rs4481233

Three SLC2A9 SNPs available in AASK and CRIC were in LD with rs13125646—the strongest signal observed among those of EA in CRIC (Table 4). There was a 0.32 mg/dL (95% CI: −0.49 to −0.14) decrease with the SLC2A9 rs13111638 minor allele (P = 0.0004), similar to the results observed in EA for rs13125646 in CRIC. Results for the other two SLC2A9 SNPs, rs6449213 and rs4481233, in close LD with rs13111638, were similar (Table 4).

Effect modification by sex in CRIC

Interactions between SLC and ABC genotypes and sex are shown in Table 5. Sex was an effect modifier for SLC2A9 rs3775948 (P = 0.0033, interaction term), SLC2A9 rs1014290 (P = 0.0079), SLC22A8 rs3793961 (P = 0.0220), SLC22A11 rs17300741 (P = 0.0003) and ABCC4 rs1751003 (P = 0.0023). Minor alleles at SLC2A9 rs3775948 (P<0.001) and rs1014290 (P < 0.001) and SLC22A11 rs17300741 (P = 0.0002) were associated with lower serum uric acid among women only. Conversely, minor alleles on SLC22A8 rs3793961 (P = 0.004) and ABCC4 rs1751003 (P = 0.0001) were associated with lower serum uric acid levels among men only.

Table 5.

Sex interaction analysis in CRIC

| Genotype | n | BETA | Uric acid mean | Uric acid adjusted mean | P-value | n | BETA | Uric acid mean | Uric acid adjusted mean | P-value | P-value interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex interaction | Men |

Women |

||||||||||

| SLC2A9 (rs3775948) | CG/CC | 995 | −0.10 | 7.72 | 7.27 | 0.1805 | 797 | −0.44 | 6.84 | 6.40 | <0.0001 | 0.0033 |

| GG | 954 | 7.67 | 7.37 | 776 | 7.15 | 6.84 | ||||||

| SLC2A9 (rs1014290) | GA/GG | 944 | −0.11 | 7.70 | 7.26 | 0.1522 | 758 | −0.41 | 6.82 | 6.41 | <0.0001 | 0.0079 |

| AA | 1005 | 7.69 | 7.37 | 814 | 7.16 | 6.82 | ||||||

| SLC22A8 (rs3793961) | AA/AG | 77 | −0.57 | 7.52 | 6.77 | 0.004 | 92 | 0.07 | 7.52 | 6.71 | 0.6923 | 0.0220 |

| GG | 1873 | 7.70 | 7.35 | 1480 | 6.96 | 6.65 | ||||||

| SLC22A11 (rs17300741) | GA/GG | 1316 | 0.06 | 7.67 | 7.34 | 0.4792 | 1020 | −0.34 | 6.77 | 6.54 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 |

| AA | 634 | 7.75 | 7.28 | 553 | 7.42 | 6.88 | ||||||

| ABCC4 (rs1751003) | AA/AG | 483 | −0.34 | 7.43 | 7.07 | 0.0001 | 363 | 0.07 | 7.05 | 6.70 | 0.486 | 0.0023 |

| GG | 1466 | 7.79 | 7.41 | 1210 | 6.98 | 6.64 | ||||||

CRIC, chronic renal insufficiency cohort; BETA, beta-coefficient from PLINK regression.

Discussion

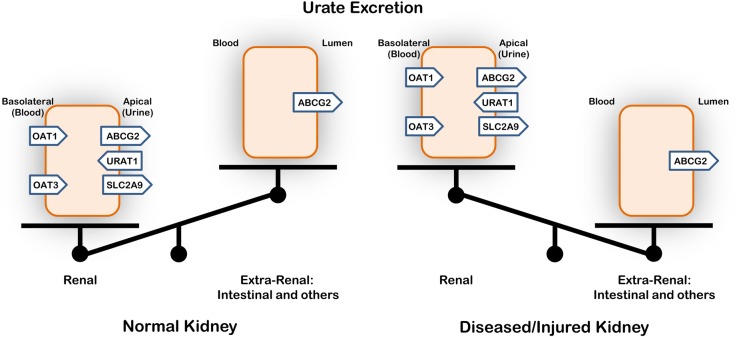

The highly significant association of ABCG2 with uric acid in patients with CKD may be one of the first human examples suggesting a likely compensatory intestinal extrusion of uric acid in patients with low GFR. Thus, as in animal studies [5], intestinal urate transport by ABCG2 compensates for abnormal urate handling in the setting of declining renal function (Figure 2). As discussed below, this result is compatible with the Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis, which describes how SLC and ABC ‘drug’ and other transporters in different tissues regulate inter-organ communication in order to maintain normal metabolism and signaling, especially after acute or chronic organ injury [3].

Fig. 2.

Uric acid excretion with normal or decreased renal function. The results of this analysis of human data—as well as physiological data from rodent models with renal dysfunction [5]—support the view that urate transport by ABCG2, most likely in the intestine, compensates for altered renal urate handling in the setting of poor kidney function.

By comparison, the association with SLC2A9, significant in patients in those of EA with CKD, was eight orders of magnitude less (∼E-5 for SLC2A9 compared with ∼E-13). In striking contrast, among those with normal renal function (the twin study), SLC2A9 but not ABCG2 was associated with altered uric acid levels, consistent with other studies [9–11]. Other SLC and ABC urate transporters such as SLC22A8 (OAT3) and ABCG (MRP4) had only weak gender-dependent effects on uric acid levels. Taken together, our data shed light on the complexity of uric acid homeostasis depending upon renal function, ethnicity and gender.

In this study, ABCG2 rs4148157 had the strongest association with serum uric acid among those of EA with CKD. The minor allele for this SNP is relatively common among East Asian populations (MAF: 0.25–0.30). Other ABCG2 SNPs have been shown to be functional with respect to uric acid transport (rs2231142 [29]) and associated with early onset gout and hyperuricemia in Japanese cohorts (rs2728125 [16, 17, 30]). Among the Japanese population, ABCG2 dysfunction may account for up to 29% of the population-attributable-risk of hyperuricemia [31]. In addition, SLC2A9 SNPs were also statistically significant among those of EA (P ≤ 5.1E-5) in the CRIC and the twin dataset, with strong (but not statistically significant) associations among those of AA. The most significant SLC22A9 SNPs (rs13125646, rs4481233 and rs1014290) are in LD and have been associated with uric acid levels and/or gout in several studies [9, 32, 33].

While SLC2A9 is primarily thought to affect uric acid transport in the proximal tubules of the kidney, the ABCG2 transporter—localized to brush border of renal proximal tubules and intestinal cells—functions to extrude urate [6–9, 14, 16, 17, 28, 30]. While site-directed mutagenesis of ABCG2 rs2231142 has been shown to significantly decrease renal uric acid transport [27], recent evidence in rodents suggests increased intestinal expression in the setting of renal failure [5]. It is also believed that ABCG2 in the intestine plays a major role in regulation of human uric acid levels [14].

Moreover, ABCG2 SNPs have been shown to be more specifically associated with gout among patients classified as ‘renal overload’, whereas SLC2A9 SNPs are most significant among those classified as ‘renal under-excretion’ [17]. However, if filtration declines in the setting of CKD, renal secretion may be limited [4]. In this setting, ABCG2—a major luminal intestinal secretory urate transporter—may in part compensate for the loss of renal excretion and thus be more important in net urate excretion in the setting of declining renal function (Figure 2). In this context, it is worth noting that ABCG2 (BCRP) is also a major drug transporter, and many of these drug transporters seem to be substrate inducible [34]. Hence, high levels of uric acid in the setting of CKD may lead to induction of urate transporters in the intestine and other non-renal tissues.

There is a growing body of data on the potential role of SLC and ABC transporters in inter-organ communication via small molecules that might include those with antioxidant properties such as uric acid [35–39]. Taken together, our data support the notion that uric acid transporters in remote organs (intestine versus kidney) may regulate serum urate levels, as suggested in the Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis [3, 35–38]. That this appears most important in the setting of chronic renal injury is also consistent with this hypothesis, which also suggests that Remote Sensing and Signaling via multispecific ABC and SLC ‘drug’ transporters is particularly critical in the setting of perturbed homeostasis due to organ injury. Moreover, because of the clustering of SLC22 transporters in the genome (human chromosome 11) and, in particular, the pairing of the SCL22A6 (OAT1) with SLC22A8 (OAT3) and SCL22A11 with SLC22A12 [40], as well as tissue-selective expression patterns (e.g. kidney versus gastrointestinal) [5, 14], it has been suggested that there might be coordinate regulation of these genes [3, 37, 40, 41].

The effects of several SLC and ABC transporters on serum uric acid also varied by gender (Table 4). Similar to other studies, SLC2A9 rs3775948 appeared only to be significant in women [11, 26–28]. The effect of SLC2A9 variation on uric acid is also influenced by environmental factors, including diet and body mass index [42]. Sex was also an effect modifier in the association between serum uric acid and SLC22A8, the association being significant among women only; in contrast, SLC22A11 and ABCC4 were significant in men only.

Probably because of differences in linkage structure and allele frequencies, the most significant SNPs were different between those of EA and AA. While associations in AA generally trended in a similar fashion to those of EA, the associations were of marginal statistical significance, even when CRIC and AASK data were combined. This is most likely the result of inadequate coverage for the AA genome on commercial chips. As CRIC is a unique study cohort with CKD, there are few comparable cohorts for replication. Thus, the role of ABCG2 in patients with CKD remains to be verified in larger clinical cohorts; the clinical significance of ABCG2 rs4148157 in populations of East Asian descent who have a relatively high MAF (∼0.30) warrants further study. Interestingly, URAT1 was not significantly associated with uric acid levels in either CRIC or the twin data set despite adequate power to detect a modest effect size in the study populations considered here.

By these analyses, we uncovered a notable highly significant association between ABCG2 serum uric acid among patients of EA with CKD, with a considerably less significant association with SLC2A9. Serum uric acid homeostasis in CKD settings may in large part be maintained by intestinal secretion by transporters such as ABCG2, suggesting that remote effects on transporters in distant tissues (i.e. intestine versus kidney) may be critical in the setting of injury to one tissue or the other [3, 38]. Results presented here indicate that transporters may be more or less dominant in serum uric acid homeostasis depending on patient population characteristics (disease state, sex, ethnicity). Alteration in uric acid levels is relatively common and genetic effects may very well depend on the patient population and be a function of medical illness (e.g. renal disease) and genetic substructure. To more thoroughly evaluate these issues, in addition to large meta-analyses that combine patient populations, it will be important for future studies to address effects in a well-characterized cohort with a focus on confounding variables and effect modification. Additional transporters, such as those of the SLC22 family, which has over 30 mammalian members [43]—several of which are known to transport urate—may eventually be implicated in human urate handling. To the best of our knowledge, the highly significant association of ABCG2 with uric acid in patients with CKD may be among the clearest human evidence to date suggesting a remote compensatory role of intestinal-expressed ABCG2 patients with low GFR, consistent with the Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis [3, 35–38]. Therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing extra-renal ABCG2 urate extrusion may have clinical value in CKD patients with hyperuricemia.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Daniel T. O'Connor. Special thanks to the CRIC study investigators, NIDDK and to Erwin Bottinger MD, The Charles Bronfman Institute for Personalized Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine Mount Sinai, for access to AASK genotype data. This work was partly supported by National Institute of Health grants RO1 GM098449 and RO1 GM104098 (S.K.N.), U54 HD07160 and NIH P30 DK079337 and R01 MH09350 (to C.M.N.).

References

- 1.Eraly SA, Vallon V, Rieg T et al. Multiple organic anion transporters contribute to net renal excretion of uric acid. Physiol Genomics 2008; 33: 180–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mount DB. The kidney in hyperuricemia and gout. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2013; 22: 216–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigam SK. What do drug transporters really do? Nature reviews Drug discovery 2015; 14: 29–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipkowitz MS. Regulation of uric acid excretion by the kidney. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012; 14: 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yano H, Tamura Y, Kobayashi K et al. Uric acid transporter ABCG2 is increased in the intestine of the 5/6 nephrectomy rat model of chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 2014; 18: 50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köttgen A, Albrecht E, Teumer A et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 145–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolz M, Johnson T, Sanna S et al. Meta-analysis of 28,141 individuals identifies common variants within five new loci that influence uric acid concentrations. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tin A, Woodward OM, Kao WHL et al. Genome-wide association study for serum urate concentrations and gout among African Americans identifies genomic risk loci and a novel URAT1 loss-of-function allele. Hum Mol Genet 2011; 20: 4056–4068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C et al. SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 437–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preitner F, Bonny O, Laverriere A et al. Glut9 is a major regulator of urate homeostasis and its genetic inactivation induces hyperuricosuria and urate nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 15501–15506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Döring A, Gieger C, Mehta D et al. SLC2A9 influences uric acid concentrations with pronounced sex-specific effects. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 430–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anzai N, Ichida K, Jutabha P et al. Plasma urate level is directly regulated by a voltage-driven urate efflux transporter URATv1 (SLC2A9) in humans. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 26834–26838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama A, Matsuo H, Shimizu T et al. Common missense variant of monocarboxylate transporter 9 (MCT9/SLC16A9) gene is associated with renal overload gout, but not with all gout susceptibility. Hum Cell 2013; 26: 133–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosomi A, Nakanishi T, Fujita T et al. Extra-renal elimination of uric acid via intestinal efflux transporter BCRP/ABCG2. PLoS One 2012; 7: e30456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuo H, Yamamoto K, Nakaoka H et al. Genome-wide association study of clinically defined gout identifies multiple risk loci and its association with clinical subtypes. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 0: 1–8. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuo H, Takada T, Ichida K et al. Common defects of ABCG2, a high-capacity urate exporter, cause gout: a function-based genetic analysis in a Japanese population. Sci Transl Med 2009; 1: 5ra11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuo H, Takada T, Nakayama A et al. ABCG2 dysfunction increases the risk of renal overload hyperuricemia. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2014; 33: 266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kratzer JT, Lanaspa MA, Murphy MN et al. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 3763–3768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM et al. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14 (7 Suppl 2): S148–S153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockburn M, Hamilton A, Zadnick J et al. The occurrence of chronic disease and other conditions in a large population-based cohort of native Californian twins. Twin Res 2002; 5: 460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Rao F, Wessel J et al. Functional allelic heterogeneity and pleiotropy of a repeat polymorphism in tyrosine hydroxylase: prediction of catecholamines and response to stress in twins. Physiol Genomics 2004; 19: 277–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T et al. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 2421–2431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lash JP, Go AS, Appel LJ et al. Chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study: baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4: 1302–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 2010; 26: 2336–2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 559–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandstatter A, Kiechl S, Kollerits B et al. Sex-specific association of the putative fructose transporter SLC2A9 variants with uric acid levels is modified by BMI. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1662–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabolić I, Asif AR, Budach WE et al. Gender differences in kidney function. Pflugers Arch 2007; 455: 397–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu M, Tomlinson B. Gender-dependent associations of uric acid levels with a polymorphism in SLC2A9 in Han Chinese patients. Scand J Rheumatol 2012; 41: 161–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward OM, Kottgen A, Coresh J et al. Identification of a urate transporter, ABCG2, with a common functional polymorphism causing gout. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 10338–10342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama A, Matsuo H, Takada T et al. ABCG2 is a high-capacity urate transporter and its genetic impairment increases serum uric acid levels in humans. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2011; 30: 1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama A, Matsuo H, Nakaoka H et al. Common dysfunctional variants of ABCG2 have stronger impact on hyperuricemia progression than typical environmental risk factors. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuo H, Chiba T, Nagamori S et al. Mutations in glucose transporter 9 gene SLC2A9 cause renal hypouricemia. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 83: 744–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabara Y, Kohara K, Kawamoto R et al. Association of four genetic loci with uric acid levels and reduced renal function: the J-SHIPP Suita study. Am J Nephrol 2010; 32: 279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martovetsky G, Tee JB, Nigam SK. Hepatocyte nuclear factors 4alpha and 1alpha regulate kidney developmental expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. Mol Pharmacol 2013; 84: 808–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn S-Y, Nigam SK. Toward a systems level understanding of organic anion and other multispecific drug transporters: a remote sensing and signaling hypothesis. Mol Pharmacol 2009; 76: 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaler G, Truong DM, Khandelwal A et al. Structural variation governs substrate specificity for organic anion transporters (OAT) homologs: potential remote sensing by oat family members. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: doi:10.1074/jbc.M703467200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nigam SK, Bush KT, Martovetsky G et al. The organic anion transporter (OAT) family: a systems biology perspective. Physiol Rev 2015; 95: 83–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu W, Dnyanmote AV, Nigam SK. Remote communication through solute carriers and ATP binding cassette drug transporter pathways: an update on the remote sensing and signaling hypothesis. Mol Pharmacol 2011; 79: 795–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nigam SK, Bush KT, Bhatnagar V. Drug and toxicant handling by the OAT organic anion transporters in the kidney and other tissues. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2007; 3: 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eraly SA, Hamilton BA, Nigam SK. Organic anion and cation transporters occur in pairs of similar and similarly expressed genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 300: 333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu G, Bhatnagar V, Wen G et al. Analyses of coding region polymorphisms in apical and basolateral human organic anion transporter (OAT) genes [OAT1 (NKT), OAT2, OAT3, OAT4, URAT (RST)]: Rapid communication. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 1491–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeroncic I, Mulic R, Klismanic Z et al. Interactions between genetic variants in glucose transporter type 9 (SLC2A9) and dietary habits in serum uric acid regulation. Croat Med J 2010; 51: 40–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu C, Nigam KB, Date RC et al. Evolutionary analysis and classification of OATs, OCTs, OCTNs and other SLC22 transporters: structure-function implications and analysis of sequence motifs. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0140569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]