Abstract

The global primary literature on Zika virus (ZIKV) (n = 233 studies and reports, up to March 1, 2016) has been compiled using a scoping review methodology to systematically identify and characterise the literature underpinning this broad topic using methods that are documented, updateable and reproducible. Our results indicate that more than half the primary literature on ZIKV has been published since 2011. The articles mainly covered three topic categories: epidemiology of ZIKV (surveillance and outbreak investigations) 56.6% (132/233), pathogenesis of ZIKV (case symptoms/ outcomes and diagnosis) 38.2% (89/233) and ZIKV studies (molecular characterisation and in vitro evaluation of the virus) 18.5% (43/233). There has been little reported in the primary literature on ZIKV vectors (12/233), surveillance for ZIKV (13/233), diagnostic tests (12/233) and transmission (10/233). Three papers reported on ZIKV prevention/control strategies, one investigated knowledge and attitudes of health professionals and two vector mapping studies were reported. The majority of studies used observational study designs, 89.7% (209/233), of which 62/233 were case studies or case series, while fewer (24/233) used experimental study designs. Several knowledge gaps were identified by this review with respect to ZIKV epidemiology, the importance of potential non-human primates and other hosts in the transmission cycle, the burden of disease in humans, and complications related to human infection with ZIKV. Historically there has been little research on ZIKV; however, given its current spread through Australasia and the Americas, research resources are now being allocated to close many of the knowledge gaps identified in this scoping review. Future updates of this project will probably demonstrate enhanced evidence and understanding of ZIKV and its impact on public health.

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) was first identified in rhesus monkeys in the Zika forest of Uganda in 1947 and has circulated in Africa and Asia relatively unnoticed for sixty years [1]. It is a Flavivirus transmitted by Aedes spp. mosquitoes, particularly Aedes aegypti, and infection is frequently asymptomatic. Clinical manifestations include rash, mild fever, arthralgia, conjunctivitis, myalgia, retro-orbital pain, headache and cutaneous maculopapular rash [2]. The epidemiology of ZIKV changed in 2007 when an outbreak occurred on Yap Island of the Federated States of Micronesia; this was the first report of infection outside of Africa or Asia. In 2013–2014 outbreaks occurred in New Caledonia, French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, Easter Island, Vanuatu, Samoa, Brazil (2015) and currently (March 2016) 31 countries in the Americas have reported autochthonous transmission [3]. With the geographic spread, a previously unreported clinical pattern began to emerge with an increase in cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome (French Polynesia) and a rise in infants born with microcephaly in Brazil [4].

A systematic summary of the global scientific knowledge regarding ZIKV and effective prevention and control measures is required to support evidence-informed decision making concerning this emerging public health issue. Scoping reviews are a synthesis method designed to address broad, often policy-driven research questions [5–7] by identifying all the relevant evidence concerning the issue and producing summaries of the findings [5,6,8]. Scoping reviews, similar to systematic reviews, follow a structured protocol for the identification and characterisation of the literature in a manner that is both reproducible and updateable [5,6,9]. Unlike a systematic review, a scoping review is well-suited to the identification of evidence on a broad topic, but does not include a quality assessment or in depth data extraction stage that would be required for meta-analysis of studies. Systematic reviews may be prioritized as a next step based on the results of a scoping review if adequate research exists on specific questions of interest [9,10]. Another important output of a scoping review is the identification of where evidence is lacking or non-existent to help direct future research and use of resources.

Objective

In response to the current ZIKV outbreaks and changes in its epidemiology, a scoping review was conducted to capture all published literature addressing the following aspects of ZIKV: 1) ZIKV infection in humans, any host or vector—pathogenesis, epidemiology, diagnosis, conditions for virus transmission, and surveillance for ZIKV, 2) studies on ZIKV—pathogenesis, transmission and molecular mechanisms, 3) prevention strategies to prevent ZIKV infections and/or control of ZIKV harbouring vectors, and 4) societal knowledge, perception and attitudes towards ZIKV.

Methods

Review protocol, team and expertise

To ensure the scoping review methods were reproducible, transparent and consistent, a scoping review protocol was developed a priori. The protocol, list of definitions, search algorithms, abstract screening form and data characterization and utility form (DCU) are available upon request. The location of the repository of relevant articles and the dataset resulting from this review is available upon request.

The review team consisted of individuals with multi-disciplinary expertise in epidemiology, microbiology, veterinary public health, knowledge synthesis and information science.

Review question and scope

This scoping review was conducted to answer the following question: What is the current state of the evidence on ZIKV pathogenesis, epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis, surveillance methods, prevention and control strategies and, knowledge, societal attitudes and perceptions towards infections in humans, mosquito vectors and animal reservoirs?

Search strategy

To ensure the search was comprehensive the term “zika” was implemented in the following bibliographic databases on January 27 2016 and updated March 1, 2016: Scopus, PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health), CAB, LILACS (South American), Agricola and the COCHRANE library for any relevant trials in the trial registry. No limits were placed on the search and it was pretested in Scopus.

The capacity of the electronic search to identify all relevant primary research was verified by hand searching the reference lists of three ZIKV risk assessments, 19 literature reviews. Reference lists of the 3 risk assessments [11–13] and 19 selected relevant literature reviews were evaluated for additional research that had been omitted by the bibliographic database search [14–29]. From this exercise 34 grey literature reports with primary information and peer-reviewed primary literature articles were identified and added to the scoping review process.

Additional grey literature was identified by hand-searching the websites of the World Health Organisation (http://www.who.int/csr/disease/zika/en/), Pan American Health Organisation (http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11585&Itemid=41688&lang=en), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html), Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/zika_reports.html), European Center for Disease Control (http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/zika_virus_infection/Pages/index.aspx) and ProMed-mail (http://www.promedmail.org/) for primary research reports, guidelines, epidemiological alerts, situation reports, surveillance bulletins and referenced publications that were not already captured. One hundred and eleven additional references were added to the project, many of these were guidelines / government reports and new articles that have not been indexed in the bibliographic databases yet.

Relevance screening and inclusion criteria

A screening form was developed a priori to screen abstracts, titles and keywords of identified citations. Primary peer-reviewed articles were considered relevant if they addressed one or more aspects of the research question, conducted anywhere and anytime. Presently only articles in English and French are included but articles in Spanish and Portuguese are identified and can be included when resources are available. Primary research was defined as original research where authors generated and reported their own data.

Study Characterisation and extraction

Complete articles of potentially relevant citations were reviewed using a data characterization and utility (DCU) form consisting of potentially 52 questions designed a priori to confirm article relevance, data utility and extraction of the main characteristics including reported information, study methodology, populations, intervention strategies, sampling, laboratory tests and outcome characteristics.

Scoping review management, data charting and analysis

All potentially relevant citations identified by the literature search were imported into reference management software (RefWorks 2.0, ProQuest LLC, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), where duplicates were manually removed; the list of unique citations was then imported into a web-based electronic systematic review management platform (DistillerSR, Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). All stages of the scoping review from relevance screening to data extraction were conducted within this software. Two reviewers independently completed all steps of the scoping review.

Data collected in the DCU form were exported into Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), formatted, and analyzed descriptively (frequencies and percentages) to facilitate categorization, charting and discussion.

Results

Scoping review descriptive statistics

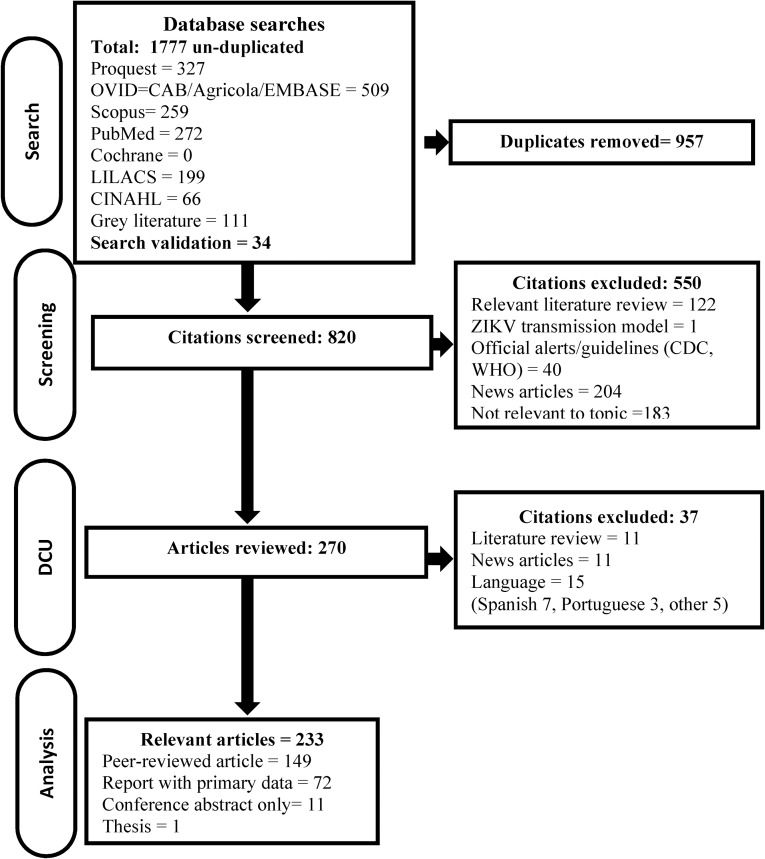

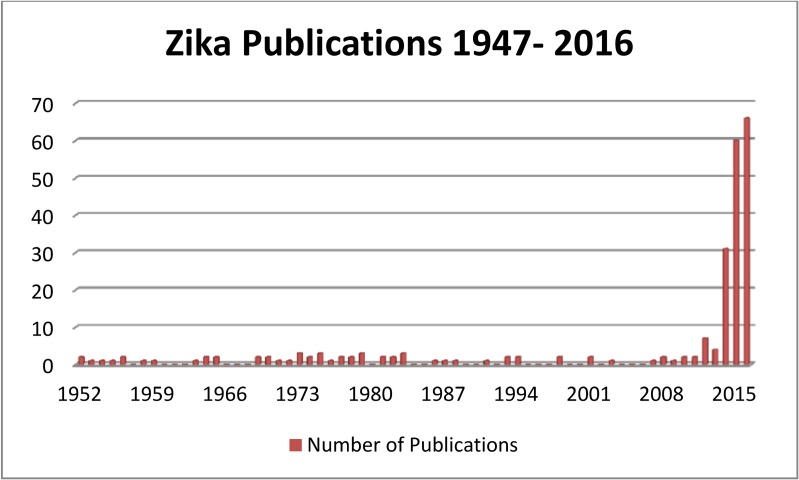

Of the 820 abstracts and titles screened for relevance, 270 were considered potentially relevant primary research/data and the full article was obtained, data was extracted and categorized for 233 relevant primary research articles in English or French, Fig 1. Research was scarce and sporadic after the virus was first isolated in 1947, until the outbreak on Yap Island, Micronesia in 2007; the majority of primary research on ZIKV has been published since 2011, 73.0% (170/233), Fig 2.

Fig 1. Flow of citations and articles through the scoping review process last updated March 1, 2016.

Fig 2. Number of primary literature publications on ZIKV by year of publication since its discovery in 1947 to search date March 1, 2016.

The general characteristics of the included articles are described in Table 1. Most included articles were peer-reviewed 63.9% (149/233) and in English 91.0% (212/233). Fifteen articles were in languages other than French and English (Spanish (7), Portuguese (3), Chinese (3), Russian (1), and German (1)) and Fig 1. The largest body of research is now from the Americas 34.87% (81/233), followed by Australasia 24.9% (58/233) and Africa, 24.0% (56/233), the remaining research was fairly evenly distributed over the other continents. The articles mainly covered three topic categories: epidemiology of ZIKV (surveillance and outbreak investigations) 56.6% (132/233), pathogenesis of ZIKV (case symptoms/ outcomes and diagnosis) 38.2% (89/233) and ZIKV studies (molecular characterisation and in vitro evaluation of the virus) 18.5% (43/233). There has been little reported in the primary literature on ZIKV vectors (12/233), ZIKV surveillance (13/233), diagnostic tests (12/233) and transmission (10/233). Three papers reported on ZIKV prevention/control strategies [30–32], one investigated knowledge and attitudes of health professionals [33] two vector mapping studies [34,35] and one ZIKV transmission model were reported [36]. The majority of studies used observational study designs, 89.7% (209/233) of which 62/233 were case studies or case series, while fewer (24/233) used experimental study designs.

Table 1. General characteristics of 233 included primary research publications.

| Category | Count | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of citation | ||

| Primary peer-reviewed | 149 | |

| Grey literature with primary data | 72 | |

| Conference proceeding | 11 | |

| Thesis | 1 | |

| Language | ||

| English | 212 | |

| French | 21 | |

| Continent | ||

| Central America/South America/Caribbean | 64 | |

| Australasia | 58 | |

| Africa | 56 | |

| Europe | 25 | |

| Asia | 20 | |

| North America | 17 | |

| Date of publication | ||

| Pre 1960 | 11 | |

| 1960–1970 | 8 | |

| 1971–1980 | 18 | |

| 1981–1990 | 10 | |

| 1991–2000 | 7 | |

| 2001–2010 | 9 | |

| 2011-Present | 170 | |

| ZIKV topic category | ||

| Epidemiology | 132 | |

| Pathogenesis | 89 | |

| Virus study | 43 | |

| Surveillance | 13 | |

| Diagnostic tests | 12 | |

| Vector study | 12 | |

| Transmission | 10 | |

| Mitigation | 3 | |

| Qualitative | 1 | |

| Other model | 1 | |

| Study design | ||

| Observational study | 209 | |

| Outbreak investigation | 67 | |

| Case study or case-series | 62 | |

| Prevalence survey | 48 | |

| Surveillance or monitoring program | 14 | |

| Cross-sectional | 7 | |

| diagnostic test evaluation | 7 | |

| Molecular epidemiology | 6 | |

| Longitudinal study | 1 | |

| Case control | 1 | |

| Experimental study | 24 | |

| Challenge trial | 22 | |

| Controlled trial | 2 | |

| Vector mapping model | 2 | |

In the 233 included articles, human populations were the most frequently reported (191/233) with 15 studies focusing solely on pediatric populations (<16 years old), Table 2. Blood was the most common sample (179/191) used to evaluate ZIKV infection or seropositivity in humans, Table 2. Monkeys were the most frequently studied non-human hosts (7/13) followed by three recent studies (4 citations) on bats from which none report ZIKV isolation, Table 2. Mice were used for the majority of animal model experiments (13/15) while monkeys were used in 4/15 studies, Table 2.

Table 2. Human and non-human host populations studied in 233 included articles.

| Category | Count | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | 191 | ||

| adults/ all ages | 176 | ||

| pediatric only | 15 | ||

| human samples | |||

| blood | 179 | ||

| urine | 16 | ||

| saliva | 10 | ||

| fetus / placenta | 8 | ||

| amniotic fluid | 5 | ||

| head circumference | 4 | ||

| cerebrospinal fluid | 4 | ||

| semen | 2 | ||

| breast milk | 2 | ||

| nasopharynx swab | 2 | ||

| conjunctivae swab | 1 | ||

| Host | 13 | ||

| bats | 4 | ||

| chicken/ duck (domestic) | 1 | ||

| domestic ruminants | 1 | ||

| horse | 1 | ||

| monkey | 7 | ||

| rodents | 2 | ||

| small mammals | 1 | ||

| wild birds | 1 | ||

| Animal model | experimental animals | 15 | |

| Mice | 13 | ||

| Non-human primates | 4 | Rhesus monkey | |

| Other animal species | 2 | cotton rats, guinea pigs, rabbits | |

| Vectors | 45 mosquito species | 26 | See Table 4 |

ZIKV virus studies

A small number of studies examined the attributes of ZIKV, Table 3. Early reports describe a 40 mμ, spherical shaped virus [37] that infects the nucleus of cells [27]. Others examined the antigenic relatedness of various Flaviviruses [26,38]. The virus growth, replication and survival in human cell lines [39] and in vivo (mice) was investigated [40] and the pathogenesis in mice has also been described [38,41,42]. The evaluation of a mouse model for virus propagation is described in three studies [42–44]; the mouse model was also used in 13 studies to identify and propagate ZIKV. In one report, researchers describe the use of chick embryos and inoculation of the yolk sac for virus propagation as being comparable to intracerebral inoculation of mice [45]. Earlier studies were identified that examined the cross neutralization tests and cross complement fixation tests on a number of new and known viruses to examine their relatedness [45] and used a monkey model to show there was no cross-immunity with yellow-fever and ZIKV [46].

Table 3. 45 studies examined the ZIKV characteristics: genotype, molecular characterisation, pathogenic attributes and virus propagation in mice.

| Number of studies | |

|---|---|

| Genotype reported: | |

| Asian lineage | 33 |

| East/Central/South African lineage (Uganda) | 9 |

| West African lineage (Senegal/Nigerian) | 5 |

| Molecular characterisation: | |

| Phylogeny was reported (e.g. dentogram, tree) | 26 |

| Virus was reported to be partially or fully sequenced | 25 |

| Evolution of the virus discussed | 12 |

| Examined proportion of nucleotide identities among strains and/or codon adaptation and fitness | 5 |

| Pathogenic attributes: | |

| Virus propagation in mice via intracerebral inoculation | 4 |

| Antigenic relatedness of Flaviviruses | 2 |

| Viral entry into cells | 2 |

| Virus morphology (ZIKV: 40 mµ, spherical in shape) | 1 |

| Presence of virus-specific antigen in the nuclei of Zika virus-infected cells (vertebrate & invertebrate) | 1 |

| Virus growth in vitro | 1 |

| Virus spread within mice | 1 |

| Virus propagation in chick embryos | 1 |

ZIKV genotype was provided in 17.6% (41/233) of studies, 36 observational studies and 5 experimental studies, Table 3 [21,32,39,46–81]. One study failed to report the genotype even though sequencing was done [82]. Due to the outbreaks in Australasia since 2007 and more recently in the Americas, many of the studies reporting genotype reported the Asian type (33/41), Table 3. With respect to studies that lend evidence to the molecular characterisation of the virus, authors frequently reported the virus had been partially sequenced, provided a gene bank number or provided a phylogenic tree in the paper [21,47,50–55,57–63,66–81,83]. A number of studies discussed ZIKV genetic relatedness other Flaviviruses and the evolution of ZIKV [47,50–54,57–59,63,68,70,83]. In a few studies the evolution of the virus (12/41) was discussed or proportions of nucleotide identities across strains (5/41) were provided in the paper. A recent paper examined codon adaptation and fitness [51] and concluded that across studies no particular mutations or evidence of adaptation to a new vector would explain the recent spread through the Pacific Islands to the Americas.

Zika Vectors

Known ZIKV vectors are all mosquitos; no evidence was identified for any other type of vector. Table 4 reports on the 26 mosquito vector studies that tested 45 different mosquito species for either a natural infection with ZIKV or evaluated the mosquito species for vector competence to transmit ZIKV. Eighteen species of mosquitos were found to be positive for ZIKV during epidemiological sampling in Africa and Asia from 1956 to 2015 and eight were evaluated experimentally for vector competence, Table 4. Ae. aegypti 15/26, and Ae. africanus 10/26 were investigated most often. Ae. albopictus, a species of particular interest as a possible vector for ZIKV in North America, was evaluated for vector competence in one study and as a naturally infected vector of ZIKV in two studies.

Table 4. Vector species evaluated in 26 studies for carriage of ZIKV or vector competence to transmit ZIKV.

| Ref | Mosquito species | Number of Studies | Challenge trials | Naturally infected with ZIKV studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Studies: | 26 | 10 | 12 | |

| [31,35,64,83–95] | Aedes aegypti | 16 | 6 | 5 |

| [31] | Aedes aegypti formosus | 1 | 1 | |

| [1,35,38,44,70,91,95–98] | Aedes africanus | 10 | 2 | 4 |

| [65,83,87] | Aedes albopictus | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| [97] | Aedes apicoargenteus | 1 | 1 | |

| [93] | Aedes argentepunctatus | 1 | ||

| [93] | Aedes cozi | 1 | ||

| [93,94] | Aedes cumminsi | 2 | ||

| [35,86,91,93,99] | Aedes dalzielii | 5 | 4 | |

| [86] | Aedes fowleri | 1 | 1 | |

| [35,86,91–94,96,99] | Aedes furcifer | 8 | 4 | |

| [85,100] | Aedes hensilii | 2 | 1 | |

| [91] | Aedes hirsutus | 1 | 1 | |

| [98] | Aedes ingrami | 1 | ||

| [35,84,86,91,93–96,99] | Aedes luteocephalus | 9 | 1 | 5 |

| [35,91,94] | Aedes metallicus | 3 | 1 | |

| [35,86] | Aedes minutus | 2 | 1 | |

| [35,86,93] | Aedes neoafricanus | 3 | 1 | |

| [70,93,94] | Aedes opok | 3 | 1 | |

| [35] | Aedes patas | 1 | ||

| [83,95] | Aedes simpsoni | 2 | ||

| [35,86,91,93,99] | Aedes taylori | 5 | 3 | |

| [84,91,93] | Aedes unilineatus | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| [85] | Aedes vexans | 1 | ||

| [35,84,86,91–93,95,99] | Aedes vittatus | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| [35] | Aedes coustani | 1 | 1 | |

| [91] | Anopheles coustani | 1 | ||

| [35,83,94] | Anopheles gambiae | 3 | ||

| [94] | Anopheles nili | 1 | ||

| [35] | Cercopithecus aethiops | 1 | ||

| [98] | Chrysops centurionis | 1 | ||

| [98] | Chrysops funebris | 1 | ||

| [85] | Coquillettidia crassipes | 1 | ||

| [98] | Culex annulioris | 1 | ||

| [85] | Culex gossi | 1 | ||

| [85] | Culex nigropunctatus | 1 | ||

| [91] | Culex perfuscus | 1 | 1 | |

| [94] | Culex poicilipes | 1 | ||

| [83,85] | Culex quinquefasciatus | 2 | ||

| [85] | Culex sitiens | 1 | ||

| [83] | Eretmapodites quinquevittatus | 1 | ||

| [85] | Lutzia fuscana | 1 | ||

| [83] | Mansonia africana | 1 | ||

| [98] | Mansonia aurites | 1 | ||

| [35,83,91,99] | Mansonia uniformis | 4 | 2 |

Experimental studies examining vector competence and feeding activity under laboratory conditions (24–29 C and 75–95% relative humidity) mainly focused on Ae. aegypti and provided data on infection rates, dissemination rates, transmission rates, minimum infection rate, entomologic inoculation rate or mean biting rate, Table 5. Studies on Ae. aegypti demonstrated that individual mosquitos held under laboratory conditions transmitted ZIKV 33–100% of the time and transmission of the virus occurred irrespective of whether the mosquito was engorged with a blood meal [90]. In one experiment infected Ae. aegypti transmitted ZIKV to a rhesus monkey 72 days post mosquito infection [89]. Mitigation by biological control was investigated in one experiment where the researcher examined the transferability of mosquito resistance to ZIKV between species (Ae. aegypti and Ae. formosus), however they concluded the resistance gene is complex and not easily manipulated [31].

Table 5. Summary of eight studies on vector competence and behaviour.

| Ref | Country | Year study conducted | Mosquito Species | Infection rate | Dissemination rate | Transmission rate | Proportion infected | Proportion disseminated ZIKV | MIR | EIR | MBR | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 3dpi | 5 dpi | 8 dpi | 10 dpi | 15 dpi | 20–60 dpi | 4 dpi | 7 dpi | 10 dpi | 15 dpi | |||||||||

| [84] | Senegal | 2015 | Ae. aegypti | highest 10dpi | 0% | 0–10% | 0–50% | 55% | 5.80% | ||||||||||

| Ae. unilineatus | highest 10dpi | 0–10% | 18.70% | 5.30% | |||||||||||||||

| Ae. vittatus | highest 10dpi | 0% | 0–100% | 0–100% | 20–50% | 14.40% | 27% | ||||||||||||

| Ae. luteocephalus | highest 15dpi | 0% | 0–100% | 20–50% | 75% | 42.20% | |||||||||||||

| [91] | Senegal | 2011/04–2011/12 | Ae. aegypti, Ae. africanus, Ae. dalzielii, Ae. furcifer, Ae. vittatus, Cx. perfuscus, Ae. taylori, Ae. hirsutus and Ae. metallicus, Ae. unilineatus, Ma. Unif, An. coustani, An. andoustani | 3–10 | 0.005–0.052 | 0.48 to 12.78 | |||||||||||||

| [90] | Senegal | 1976 | Ae. aegypti | 88% | 79–100% (7–30 dpi)/ titer 2–6 | ||||||||||||||

| [89] | Nigeria | 1956 | Ae. aegypti | 10 3.4 | 104.7 to 5.6 | ||||||||||||||

| Asia | |||||||||||||||||||

| [65] | Singapore | 2013 | Ae. albopictus | 100% at 3dpi | 25%+ | 50%+ | 100% + | 100%+ | 100%+ | first isolate+ | 100%+ | ||||||||

| [64] | Singapore | 2012 | Ae. aegypti | 87.5% at 3 dpi, 100% at 6 dpi | first obs 4 dpi + | 62%+ | 100%+ | 100%+ | |||||||||||

| [85,100] | Yap island | 2007/04–2007/07 | Ae. (Stegomyia) hensilii | 7.1% (4.9 titre*) | 0% (4.9% titer*) | ||||||||||||||

| 80% (5.7 titer*) | 12.5% (5.7 titer*) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 86.1% (5.9 titre*) | 22.5% (5.9 titer*) | ||||||||||||||||||

* log10 pfu/ml, environment "humid" and 28C, dpi = days post infection,

+ dissemination rate = divide the number of infected salivary glands by the total number of mosquitoes with infected midgets. Transmission rate = divide the number of positive saliva by the number of infected salivary glands. MIR = Minimum infection rate, estimated number of positive mosquitoes per 1000 mosquitoes tested. EIR = Entomologic inoculation rate, number of infected mosquito bites per person, per evening. MBR = mean biting rate, number of female mosquitoes captured per person per evening

Active mosquito surveillance programs were reported in three studies in Uganda, Senegal and Burkina Faso between 1946 and 1986, where routine samples were collected [35,94,97]. Studies that conducted surveillance activities or prevalence surveys of mosquitos for ZIKV were identified from Africa and Asia and several species were implicated as possible vectors including Ae. aegypti (5 studies) and Ae. albopictus (1 study), Table 6. The results of the studies in Table 6 were not necessarily conducted when ZIKV was actively circulating.

Table 6. Twelve studies from Africa and Asia between 1956 and 2011 that sampled mosquitos for ZIKV.

Studies were conducted as prevalence surveys or part of entomological surveillance for arboviruses.

| Ref | Country | Date / place of sampling | ZIKV positive mosquito species | Positive/N | Other epidemiological information | Other mosquito species tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | ||||||

| [94] | Burkina Faso | 1984/09–1984/11: area not specified | Ae. furcifer, Ae. luteocephalus, Ae. opok | 9/ 1853 pools | Based on entomological arbovirus surveillance 1983–1986. | Ae. aegypti, Cx. poicilipes, Ae.metallicus, Ae. cumminsi, Anopheles gambiae, An. nili |

| [92] | Côte d’Ivoire | 1999: area not specified | Ae. vittatus, Ae. furcifer, Ae. aegypti. | 3/159 pools | ||

| [83] | Gabon | 2007: Libreville suburbs | Ae. albopictus | 2/247 pools | First isolation of ZIKV in Gabon in 2007 during a simultaneous outbreak of Chikungunya and Dengue. | Ae. aegypti, Cx quinquefasciatus, Ae. simpsoni complex, An. gambiae, M. africana, M. uniformis, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Eretmapodites quinquevittatus |

| [95] | Nigeria | 1969: Jos Plateau | Ae. luteocephalus | 2/205 pools | Ae. aegypti, Ae. africanus, Ae. vittatus, Ae. simpsoni | |

| [91] | Senegal | 2011/06–2011/12: Kedougou area | Ae. luteocephalus (5 pools), Ae. africanus (5), Ae. vittatus (3), Ae. taylori (2), Ae. dalzielii (2), Ae. hirsutus (2) and Ae. metallicus (2), Ae. aegypti (1), Ae. unilineatus (1), M. uniformis (1), Cx. perfuscus (1), An. coustani (1) | 31/1700 pools | Thirty-one ZIKV infected pools: June (9.7%), September (32.2%), October (35.5%), November (19.3%) and December (3.2%) | An. coustani, Ae. andoustani, Ae. furcifer |

| [93] | Senegal | 1990: Senegal | Ae. aegypti, Ae. dalzielii, Ae. luteocephalus | 3/151 pools | Ae. taylor, Ae. unilineatus, Ae. cozi, Ae. neoafricanus, Ae. opok, Ae. cumminsii, Ae. argentepunctatus, Ae. furcifer, Ae. vittatus | |

| [86] | Senegal | 1988: Southern Senegal | Ae. furcifer (25/62 pools), Ae. aegypti, Ae. dalzielii, Ae. taylori, Ae. neoafricanus, Ae. fowleri, Ae. minutus | 27/435 pools | ZIKV seemed to have an epizootic annual cycle. In 16 ZIKV positive pools, dengue-2 was also isolated. | |

| 1989: Southern Senegal | 29/654 pools | |||||

| 1990: Southern Senegal | 3/497 pools | |||||

| 1991: Southern Senegal | 3/1264 pools | |||||

| [99] | Senegal | 1972: area not specified | Ae. dalzielii, Ae. furcifer, Ae. luteocephalus, Ae. vittatus, Ae. taylori, M. uniformis | 2/204 | 130,000 mosquitos from 69 different species were examined 1972–77. | |

| 1973: area not specified | 16/798 | |||||

| 1976: area not specified | 19/599 pools | |||||

| [38] | Uganda | 1956/05–1956/08: Lunya forest | Ae. africanus | 2/11 pools | 11 pools = 1355 mosquitos | |

| [98] | Uganda | 1961/11–1963/06: Zika forest | Ae. africanus | 13/688 pools | Positive pools occurred 1962/05-1962/09 and 1962/11. | M. aurites, C. centurionis, C. funebris, C. annulioris, A. ingrami |

| [97] | Uganda | 1969–1970: Zika Forest | Ae. africanus (14 isolates), Ae. apicoargenteus (1) | 15/105 pools | No ZIKV isolation for 6 years and 73 days (since 1962/11): 8 isolations 1969/04–1969/06 and a 192 day lapse before 7 isolations 1970/04–1970/08. | |

| Asia | ||||||

| [87] | Malaysia | 1966: Bentong | Ae. aegypti | 1/296 pools | (pools- mosquitos) Ae. aegypti (58–1,277), Ae. albopictus (59–4492), 23 other Aedes species (179–27636) |

Several epidemiological studies examining risk factors for mosquito abundance, human exposure to mosquitos and conditions for ZIKV infected mosquitos were identified by the scoping review. Observations include some mosquito species such as Ae. aegypti are well suited to urban environments, are often trapped within homes [87] and are able to reproduce in water containers which are frequently found in homes. For example, on Yap Island during the 2007 outbreak 87% of the homes were found to have mosquito infested water containers [85,100]. Biting behaviour of mosquitos was shown to increase in the two months following rainfall and decreased at temperatures less than 13°C [97]. A study conducted in Senegal found the forest canopy and forest ground areas were more likely to yield ZIKV positive mosquitoes [91]. From 13 species of mosquitos examined, Ae. furcifer showed significant temporal variation and Ae. luteocephalus and Ae. taylori showed a significant correlation between biting and infection rates with a one month lag time [91].

A vector mapping model based on mosquito data collected in Senegal between 1972 and 2008 demonstrated ZIKV was not correlated with the incidence of other viruses, the abundance of mosquitos, mean temperature or humidity [35]. However, ZIKV was shown to increase 12% (95% CI = 5%-21%) for each additional inch of rain above the baseline, was positively correlated with Chikungunya virus at a 6 year lag time, and was correlated with Ae. fuciferi and Ae. taylori at a 13 year lag time [35]. The minimum infection rate for Ae. furcifer and Ae. taylori was 80% (95% CI = 41%-94%) lower than for Ae. luteocephalus [35].

Non-human hosts of ZIKV

Zika virus was first isolated in 1947 in a rhesus sentinel monkey used for yellow fever surveillance [1]. Subsequent studies in Africa to evaluate potential hosts of ZIKV examined a number of small mammals in the Zika forest and bats in Uganda, but failed to identify ZIKV or seroreactivity to ZIKV in any sample, Table 7 [98,101]. Surveys of various monkeys in Uganda, Gabon and Burkina Faso showed a range of seroprevalence for ZIKV from 0% to >50% in some species, Table 7 [97,102–104]. Surveys from Indonesia (1978) and Pakistan (1983) sampled a number of rodents, bats, wild birds and domestic livestock; they reported some ZIKV seropositivity in rodents, bats, ducks, horses and large domestic livestock [28,105]. One study, published in two papers, on the orangutans in the Sabah region of Malaysia reported a higher seroprevalence among free-ranging orangutans compared to the semi-captive group and higher seroprevalence among humans than orangutans [22,23]. They hypothesize that ZIKV among orangutans may be incidental infections from mosquitos that had contact with viremic humans or another sylvatic cycle [22,23]. At this time it has been experimentally demonstrated that infected mosquitos can transmit ZIKV to mice and monkeys under controlled laboratory conditions [89]. However, no studies were identified that examined the relative importance of non-human primates or other potential hosts compared to humans in the transmission cycle of ZIKV.

Table 7. Potential host populations sampled for ZIKV in nine studies conducted between 1952 and 2016.

| Ref | Country | Date / place of sampling | Population sampled (positive/N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||

| [104] | Burkina Faso | 1983–1984 | Monkey, not specified (0/9) |

| [103] | Gabon | 1979–1980: | Monkey, Simian (9/34) |

| [101] | Uganda | 2009–2013: area not described | Bats (0/1067) |

| [106] | Uganda, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo | 2011–2012 | Bats (conference proceeding, no data) |

| [107] | Uganda | after 2011 | Bats (conference proceeding, no data) |

| [102] | Uganda | 1972: Entebbe area | Monkey (9/21): grey vervet and red tail |

| [97] | Uganda | 1969–1970: Around Kisubi forest and Bwame forest | Monkeys: vervet monkey (23/52), redtail monkey (4/21), mona monkey (0/1), black mangabey (2/4), lowland colobus (5/11), others (7/16) |

| [98] | Uganda | 1962–1963: Zika forest | (0/25) "small mammals": 1 potto, 3 palm civets, 4 squirrels, 2 tree rats, 7 giant pouched rats, 8 field rats |

| [1] | Uganda | 1947/04: Zika forest | (1/1) Rhesus sentinel monkey: first identification of ZIKV |

| Asia | |||

| [28] | Indonesia | 1978: Lombok | Horse (3/15), cow (4/41), carabao (1/13), goat (7/35), chicken (0/78), duck (2/52), bat (6/71), rat (0/25), wild bird (0/17) |

| [22] [23] | Malaysia | 1996–1998: Sabah region | Orangutans semi- captive (1/31) and free-ranging (5/40) |

| [105] | Pakistan | 1983: Pakistan | Rodents: Tatera indicia (3/47), Meriones hurrianae (2/33), Bandicota bengalensis (1/2) cow (0/45), buffalo (0/33), sheep (1/46), goat (1/48) |

Pathogenesis of ZIKV infection in rhesus monkeys has been described for two animals; the initial sentinel monkey developed fever and was viremic on day 3 of the fever. The second monkey who was subcutaneously challenged with ZIKV showed no signs of disease, but was viremic on days 4–5 and tested seropositive 30 days after exposure [1,44]. Mice were primarily used across 13 laboratory studies published between 1952 and 1976 to study pathogenesis, transmission and to propagate ZIKV, Table 8 [1,38,42,44]. Pathogenesis of ZIKV infection in mice mainly consists of degeneration of nerve cells, wide-spread softening of the brain and often porencephaly [38,42], with little effect on other major organs [38]. In one experiment challenged rats, guinea pigs and rabbits did not show signs of illness, however, the rabbits became seropositive while the guinea pigs died [38]. No ZIKV could be identified in the guinea pigs to indicate the virus had a role in the deaths [38].

Table 8. List of studies that used an animal model to propagate ZIKV or investigate the pathology and transmission of ZIKV in mice, monkeys or other laboratory animals.

| Ref | Country | Year | Study objective | Animal model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | England | 1976 | Pathogenesis | mice |

| [42] | England | 1971 | Pathogenesis | mice |

| [46] | Uganda | 1970 | ZIKV cross-immunity with yellow fever | rhesus and vervet monkeys |

| [87] | Malaysia | 1969 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| [98] | Uganda | 1964 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| [108] | Malaysia, Thailand and N. Vietnam. | 1963 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| [38] | Uganda | 1958 | Histopathogenesis | mice |

| [89] | Nigeria | 1956 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| [88] | Nigeria | 1956 | Transmission | mice |

| [41] | United States | 1955 | Histopathogenesis | mice |

| [43] | Nigeria | 1954 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| [37] | United States | 1953 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| [1] | Uganda | 1952 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| Transmission | Rhesus monkey | |||

| [44] | Uganda | 1952 | ZIKV propagation | mice |

| Isolation | rhesus monkey | |||

| Pathogenesis | cotton rats, guinea pigs, rabbits | |||

| [45] | Uganda and Tanzania | 1951 | ZIKV propagation | chick embryo |

ZIKV in humans

Epidemiology

Studies investigating the epidemiology of ZIKV in humans (120/233) provided prevalence estimates (46) or summarized an outbreak situation (74) from 1952–2016 and included the following healthy populations: general and pediatric populations, blood donors and military personnel and acute viral fever patients as indicated in Table 9. The majority of the prevalence surveys and outbreak reports were from the Americas (44), Asia/Australasia (42) and Africa (30); some reported for more than one region. Risk factors for testing ZIKV positive were examined in three studies. On Yap Island, a study found men 77% [95% CI, 72% to 83%] were more likely to have IgM antibodies against ZIKV virus compared to women 68% [95% CI, 62% to 74%], which was a relative risk of 1.1 [95% CI, 1.0 to 1.2] [100]. Higher density housing was significantly associated with increased risk of arbovirus infections in Kenya (1970) [109]. A recent study from Zambia found that indoor residual spraying had an adjusted odds ratio of 0.81, 95% CI [0.66, 0.99] and having an iron sheet roof on the home was protective against being ZIKV seropositive. However, increasing age, farming and having a grass roof significantly increased the risk of being ZIKV seropositive [110].

Table 9. One hundred and twenty prevalence studies and outbreak reports that report ZIKV infection in human populations published between 1952 and 2016.

| Ref | Country | Date / place of sampling | Population sampled | Measure-ment | Prevalence/ Rate | Positive / N | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||||||

| [111] | Angola | 1960: several regions | General population- adults | Prevalence | 27.0% | 133/492 | (20/42 Neutralization test positive) |

| [112] | Burundi | 1980–1982: many areas | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 1.4% | 9/623 | |

| [113] | Cameroon | 2010: Buea and Tiko in the Fako division (80% of the population) | All ages- hospital submissions | Prevalence | 38.0% | 30/79 | |

| [114] | Cameroon | 1972: several areas | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 7.0% | 83/1186 | |

| [115] | Cape Verde | 2015/09/27–2015/12/06 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 4744 cases | 165 (sept 27-Oct14) and 4744 (Sept 27- Dec 6) suspected cases. (17 confirmed) | |

| [116] | Cape Verde | 2015/10–2016/01/17 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 7081 cases | ||

| [117] | Cape Verde | 2015/10–2016/01/31 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 7258 cases | ||

| [118] | Central African Republic | 1979: M'Bomou region (population of 30 000) | General population- adults | Prevalence | 59.0% | 271/459 | Prevalence: Bangassou 47%/111, M'Ballazime 62.4%/125, Iongofongo 68.5%/162, Ouango 47.5%/61 |

| [92] | Côte d’Ivoire | 1999/08: Kakpin | Adult | Prevalence | 54.2% | 13/24 | |

| [119] | Ethiopia | 2013: Dire Dawa town | All ages- hospital submissions | Prevalence | 10.0% | 5/50 | |

| [83] | Gabon | 2007–2010: entire country | All ages- hospital submissions | Prevalence | 0.1% | 4/4312 | |

| [103] | Gabon | 1979/10–1980/03: Franceville | General population- adults | Prevalence | 14.7% | 29/197 | |

| [120] | Gabon | 1975: South East Gabon | General population- adults | Prevalence | ?/1276 | ZIKV positive number not specified | |

| [121] | Guinea | 2010: N'Zerekore and Faranah | All ages- hospital submissions | Prevalence | ?/151, number ZIKV positive not reported. | ||

| [122,123] | Kenya | 2013: Kenya | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 0.0% | 0/351 | |

| [124] | Kenya | 1969: Ahero | Paediatric- school age children | Prevalence | 7.2% | 40/559 | |

| [109] | Kenya | 1966–1968: Central Nyanza, Kitui district, Malindi district | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 17.6% | 475/2698 | Prevalence: Central Nyanza 3.3%, Kitui district 1.3%, Malindi district 52% |

| [125] | Nigeria | 1980: near Kainji Dam | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 56.2% | 150/267 | |

| [126] | Nigeria | 1975: Igbo-Ora | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 20.0% | 4/20 | 1 virus isolation |

| [127] | Nigeria | 1971–1974: Oshogbo, Igbo-Ora, Ibadan and Oyo. | General population- pediatric | Prevalence | 27.0% | 51/189 | 2 ZIKV isolations /10778 samples |

| [128] | Nigeria | 1965: Benue Plateau State | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 21.4% | 15/70 | |

| [128] | Nigeria | 1970–1971: Benue Plateau State | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 12.2% | 18/147 | Samples taken during a yellow fever outbreak 1970 |

| [129] | Nigeria | 1964–1970: whole country | Paediatric- hospital submissions | Prevalence | 0.0% | 3/12613 | 3 ZIKV isolates were from 1968/ from 171 isolated arboviruses |

| [43] | Nigeria | 1952: Uburu | General population- adults | Prevalence | 59.5% | 50/84 | |

| [130] | Nigeria | 1955: Ilobi | all ages | Prevalence | 55.1% | 114/207 | |

| [130] | Nigeria | 1951: Ilaro | all ages | Prevalence | 44.3% | 43/97 | |

| [131] | Senegal | 2009/07–2013/03: eastern Senegal (population:141 226) | Adults- clinic submissions | prevalence | 0.1% | 9/13845 | All 9 IgM ZIKV positive cases were in 2011 only. |

| [86] | Senegal | 1990: Southern Senegal | General population- adults | Prevalence | 2.8% | 11/396 | |

| [86] | Senegal | 1988: Southern Senegal | General population- adults | Prevalence | 10.1% | 46/456 | |

| [132] | Senegal | 1972–5: several areas | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 58.3% | 1432/2457 | |

| [133] | Sierra Leone | 1972: several areas | Paediatric | Prevalence | 6.9% | 62/899 | |

| [44] | Uganda | 1952 Zika forest, Kampala, Bwamba, West Nile areas | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 6.1% | 6/99 | Prevalence: Zika forest 0%, Kampala 0%, Bwamba 20%, West Nile 9.5%. |

| [45] | Uganda and Tanzania | 1951: not reported | General population- all ages | Prevalence | ?/127 | Order of prevalence: Bwamba > Ntaya > ZIKV > Uganda S > West Nile > Bunyamwera > Semliki Forest viruses | |

| [110] | Zambia | 2010: Western and North-Western province | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 6.0% | 217/3625 | |

| Asia / Australasia | |||||||

| [134–136] | American Samoa | up to 2016-02-07 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 551 cases (2 confirmed) | ||

| [137–142] | Cook Islands | 2014 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 932 cases (18 confirmed and 50/80 in Tahiti confirmed.) | ||

| [79,138] | Easter Island (Chile) | 2014/01–2014/06: Easter Island | General population- all ages | Outbreak prevalence | 2.3% | 89/3860 | Easter Island population = 3860 |

| [143] | Fiji | 2014/08/ | General population- all ages | Outbreak | . | 2/6 suspect cases were ZIKV confirmed | |

| [72,116, 139,144–148] | French Polynesia | 2013/10/30–2014/04 | General population- all ages | Outbreak Attack rate | 12% (10–40 depending on the island) | 32000/268207 | 8750 suspected cases. (383–460 confirmed) Estimate: 32000 cases, 11% of the population 268, 207 on 67 islands |

| [144] | French Polynesia | 2014/02/04–2014/03/13 | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 41.3% | Estimated that 50% of people were asymptomatic | |

| [137] | French Polynesia | 2013–2014: French Polynesia | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 8746 cases (>30000 medical consultations) | ||

| [71,147] | French Polynesia | 2013/11–2014/02: French Polynesia | Adult- blood donors | Outbreak prevalence | 2.8% | 42/1505 | 11/42 reported ZIKV like illness 3 to 10 days after donation |

| [149] | French Polynesia | 2011/07–2013/10: French Polynesia | Adults- blood donors | Prevalence | 0.8% | 5/593 | |

| [53] | Indonesia | 2014/12-2015/04 | All ages- hospital submissions dengue negative | Prevalence | 1% | 1/103 | |

| [150] | Indonesia | 2004–2005: Bandung, West Java | All ages- hospital submissions dengue negative | Prevalence | ?/95, number ZIKV positive not reported. | ||

| [28] | Indonesia | 1978: Lombok | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 2.0% | 9/446 | |

| [151] | Indonesia | 1973: Tamampu, Malili, Balikpapan (South Sulawesi and East Kalimantan) | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 9.5% | 21/222 | Prevalence: 27/160 Timampu, 24/40 Malili, 20/22 Balikpapan |

| [23] | Malaysia | 1996–1997: Borneo | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 44.1% | 9/30 native & 40/81 immigrant | |

| [108] | Malaysia | 1953–4: Kuala Lumpur | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 75.0% | 75/100 | |

| [135] | Marshall Islands | 2016/02/14 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | First confirmed case. 1/6 suspect cases positive ZIKV | ||

| [137–139,142, 152,153] | New Caledonia | 2013/11–2014/07 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1400 cases | ||

| [105] | Pakistan | 1983 | Adult | Prevalence | 2.3% | 1/43 | |

| [154–156] | Samoa | 2015/09–2015/12/06 | Gen pop- all ages | Outbreak | 3/40 suspect cases were confirmed. | ||

| [140,157–165] | Solomon Islands | 2015/02–2015/05/24 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 310 cases (5 confirmed) | ||

| [166] | Thailand | 2015: Northern Thailand | Adult | Prevalence | 80% | 16/21 | 16/21 showed sero-reactivity to ZIKV, only 2 exclusively to ZIKV |

| [108] | Thailand | 1954: Thailand | Adult | Prevalence | 16.0% | 8/25 south & 0/25 north | |

| [135, 167,168] | Tonga | 2016/01–2016/02/14 | gen pop- all ages | outbreak | . | > 800 suspect cases and 2 confirmed | |

| [157,162] | Vanuatu | 2015/04/26 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1st confirmed case | ||

| [108] | Vietnam | 1954: North Vietnam, River Delta of Tomkin area | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 4.0% | 2/50 | |

| [100, 147] | Yap Island, Micronesia | 2007/04/01–2007/08/09 | General population- all ages | Outbreak prevalence | 74.3% | 414/557 sero-prevalence | Yap Island had a population of 7391 at time of outbreak RT-PCR positive |

| Outbreak prevalence | 14.5% | 185/1276 | |||||

| attack rate | 14.6/1000 persons | Ranged 3.6–21.5/1000 by community | |||||

| Infection rate | 73% (95% CI, 68 to 77) | ||||||

| Clinical symptoms | 18% (95% CI, 10 to 27) | 919 (95% CI, 480 to 1357)/6892 | |||||

| South and Central America | |||||||

| [169] | Barbados | 2016/01/14-15 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 3 cases: autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| [117,170] | Brazil | 2015/05–2015/02 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 497593–1 482 701 cases estimated (they stopped counting) | ||

| [4,171, 172] | Brazil | 2015/05-2015/12/01 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 3 fatalities: One man with co-morbidities, one healthy 20 year old woman and an infant. | ||

| [173] | Brazil | 2015/02–2015/06: Salvador Brazil | General population- all ages | Outbreak attack rate | 5.5 cases/1000 persons | 14835 cases (not confirmed) | |

| [174] | Bolivia | 2016-01-08 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1 case: autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| [117,170,175] | Colombia | 2015/10/31–2016/02/06 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 31 555 cases (1504 confirmed) | ||

| [116] | Colombia | 2015/10/31–2016/01/23 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 20297 cases | ||

| [176] | Colombia | 2015/09/22–2016/01/02 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 11712 cases (746 confirmed) and 1 fatality: sickle cell disease (previously associated with severe dengue symptoms) | ||

| [4,54, 171] | Colombia | 2015/10/31–2015/12/01 | All ages | Outbreak | autochthonous transmission 9/22 confirmed cases Sincelejo area | ||

| [177] | Dominican Republic | 2016/01/23 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 10 cases; autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| [169] | Ecuador | 2016/01/14-15 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 2 cases; autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| [116,178] | El Salvador | 2015/11–2015/12/31 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 3836 suspect cases, 46 hospitalizations and 1 death; patient had many co-morbidities | ||

| [4] | El Salvador | 2015/11–2015/12/01 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | autochthonous transmission 2015/11 | ||

| [179] | French Guiana | 2015-12-21 | General population- all ages | 1 case; autochthonous transmission 2015/12 | |||

| [4,180] | Guatemala | 2015/11–2015/12/01 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | autochthonous transmission 2015/11 | ||

| [181,182] | Guadeloupe | 1015/11/23–2016/01/21 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1 case confirmed | ||

| [169,181] | Guyana | 1015/11/23–2016/01/21 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 164 cases (45 confirmed) autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| [183] | Haiti | 2016/01/18 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 5 cases, autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| [184] | Honduras | 2015/12/21 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1 case, autochthonous transmission 2015/12 | ||

| [179,181] | Martinique | 1015/11/23–2016/01/21 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1255 cases (102 confirmed), autochthonous transmission 2015/12 | ||

| [4,185] | Mexico | 2015/11–2015/12/01 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | autochthonous transmission 2015/11 | ||

| [186,187] | Panama | 2015/11–2015/12/14 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 95 cases, (4 confirmed) autochthonous transmission 2015/12 | ||

| [4,188] | Paraguay | 2015/11–2015/12/01 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 6 cases, autochthonous transmission 2015/11 on Brazilian border | ||

| [189,190] | Puerto Rico | 2015/11/23-2016/01/28 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 155 cases (30/73 confirmed), 3 hospitalizations. autochthonous transmission 2015/11 | ||

| [181] | St. Barthelemy | 2015/11/23–2016/01/21 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | |||

| [181,182] | St. Martin | 2015/11/23–2016/01/21 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1 case confirmed | ||

| [4,191, 192] | Suriname | 2015/11 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 5/6 cases confirmed. autochthonous transmission reported November 2015 | ||

| [193] | Trinidad | 1953–1954: Trinidad | General population- all ages | Prevalence | 0.0% | 0/15 | |

| [4,194] | Venezuela | 2015/11–2015/12/01 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 7 cases (4 confirmed) autochthonous transmission 2015/11 on Brazilian border | ||

| [195] | Virgin Islands (US) | 2016/01/25 | General population- all ages | Outbreak | 1 case, autochthonous transmission 2016/01 | ||

| Travel related- notifiable disease report | |||||||

| [196] | New Zealand | 2015: New Zealand | General population- all ages | Incidence rate | 0.1 per 100,000 | 6 cases | |

| [197] | New Zealand | 2014: New Zealand | General population- all ages | Incidence rate | 1.3 per 100,000 | 57 cases total | |

| [198] | Europe | up to 2016/02/25 | General population- all ages | 177 cases from 15 countries. Austria (1), Czech Rep (2), Denmark (1), Finland (2), France (66), Germany (20), Ireland (3), Italy (6), Malta (1), Netherlands (30), Portugal (7), Spain (27), Sweden (2), Slovenia (1), UK (8). | |||

Clinical Symptoms, Complications and Pathogenesis

Clinical symptoms associated with ZIKV illness in humans is reported in 72 studies and described in Table 10, including the first experimentally challenged human case recorded in Nigeria (1956) [88] to present cases in South America and the Caribbean region. Thirty four studies report travel related cases in individuals returning from various affected countries. Thirty five studies report on complications with ZIKV, Table 11. Publications that described the clinical features of ZIKV infection in humans were mainly case reports/case series (57/78), epidemiological surveys (12/78), outbreak investigations (11/78), and one human challenge experiment (some studies fell into multiple categories). For most studies (58/78) the total number of cases was <6 while other results summarized the clinical features of up to 13,786 cases. The majority of studies have been published in the past decade and are based on ZIKV acquired infections in South-Central America and Caribbean region (54/75) and Asia/Australasia (48/75) with a number of publications reporting on both regions. A wide range of clinical symptoms are reported for ZIKV infection, most common are mild fever and a maculopapular rash followed by joint pain, headache and more recently bilateral conjunctivitis; see the summary at the bottom of Table 10 for averages across studies. In a recent study, researchers found an association with more severe symptoms in patients that were co-infected with malaria [131]. Six studies reported co-infections with dengue and/or chikungunya [74,116,117,144,146,199], one study reported co-infection with Influenza B and another with Human Immunodeficiency Virus [81,189]. Some of these studies provide evidence for the viremic period, suggested which samples and diagnostic tests to use at various stages of infection and the possible range of incubation periods, however, only one study investigated the immune response in humans [200]. Tappe (2015), investigated the role of cytokines and chemokines in the pathogenesis of ZIKV infected patients from the acute stage (≤ 10 days after symptom onset) to convalescent stage (> 10 days after disease onset) [200].

Table 10. Pathogenesis: Studies (n = 72) reporting on clinical symptoms in humans from the first experimentally challenged human in Nigeria (1956) to present (March 1, 2016) cases in the South America and Caribbean region divided by studies with n>6 (25.4%) and n<6 (74.6%).

| Ref | Study Year | Country of ZIKV Exposure | N | Fever | Joint pain | Rash Rash | Con-junc-tivitis | Muscle pain | Head-ache | Retro-orbit-al pain | Edema | Lymphadenopathy | Malaise | Asthenia | Sore throat/ cough | Nausea/ vomiting/ diarrhea | Hemato-spermia | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak Investigations, Cohort or cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||||||||||

| South- Central America and Caribbean | ||||||||||||||||||

| [173] | 2015 | Brazil | 13786 | 35% | 27% | 100% | 22% | 26% | Summary of the clinical picture from indeterminate acute exanthematous illness in Salvador, Brazil. Many cases not confirmed. | |||||||||

| [73] | 2015 | Brazil | 24 | 38% | 86% | 54% | 58% | |||||||||||

| [201] | 2015 | Brazil | 29 | 45% | 38% | 72% | 79% | 17% | 14% itchy | |||||||||

| [202] | 2015 | Brazil | 10 | 70% | 70% | 70% | 100% microcephaly in infant. | |||||||||||

| [76] | 2015 | Brazil | 8 | 75% | 88% | 100% | 75% | 75% | 50% | 75% | 38% | 8/8/ Pain scale applied to six cases -pain levels high in most patients, with levels of zero (1/7), seven (2/7), nine (1/7) or 10 (2/7). Duration 2–15 days. | ||||||

| [79] | 2014 | Easter Island (Chile) | 89 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Clinical picture of the 89 positive cases on Easter Island (total population 3860) | |||||||||

| [177] | 2016 | Dominican Republic | 10 | 100% | 60% | 100% | 80% | 50% | 60% | 60% | ||||||||

| [188] | 2015 | Paraguay | 6 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||

| [189] | 2015–2016 | Puerto Rico | 30 | 73% | 73% | 77% | 77% | 3% | 3% chills and abdominal pain | |||||||||

| [61] | 2015/10 | Suriname | 5 | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||||

| Asia and Australasia | ||||||||||||||||||

| [144–146] | 2013–14 | French Polynesia | 297 | 72% | 65% | 93% | 63% | 44% | 46% | 16% | 47% | 78% | 23% | 28% | Adenopathies 15%, mouth ulcers 4% | |||

| [203] | 2014 | New Caledonia | 6 | 83% | 67% | 100% | 50% | 67% | 17% | 17% | 50% | 17% | 6/6 itching | |||||

| [77] | 2012 | Thailand | 7 | 100% | 29% | 100% | 29% | 29% | 14% | 29% | 1/7 Rhinorrhea | |||||||

| [100,147] | 2007 | Yap Island, Micronesia | 31 | 65% | 65% | 90% | 55% | 48% | 45% | 39% | 19% | 10% | Clinical picture of 31 confirmed cases identified during a survey of 173 randomly selected households on Yap Island during the outbreak in 2007. | |||||

| [204] | 1977 | Indonesia | 7 | 100% | 29% | 14% | 14% | 14% | 86% | 43% | 1/7 haematuria, 4/7 anorexia, 2/7 chills, 5/7 stomach ache, 3/7 dizziness, 3/7 constipations, 2/7 hypotension, | |||||||

| Case Studies < 5 people | ||||||||||||||||||

| South- Central America and Caribbean | ||||||||||||||||||

| [205] | 2016 | Brazil | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | bilateral ocular discomfort, blurry vision, and mild redness on day 7 | |||||||||||

| [206] | 2015 | Brazil | 3 | 33% | 33% | Pregnant mothers—no laboratory confirmation | ||||||||||||

| [81] | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Case had HIV. | |||||||||

| [207] | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [52] | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% itchy | |||||||||||

| [55] | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% itchy | |||||||||

| [208] | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% chills | ||||||||

| [176] | 2015 | Colombia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% Abdominal pain and jandice. Comorbidity: Sickle cell disease (>5 yrs). Patient died. | ||||||||||

| [209] | 2015 | Colombia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||

| [199] | 2015 | Colombia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Case had co-infection with dengue and chikungunya. | |||||||||

| [210] | 2016 | Costa Rica | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [211] | 2016 | Costa Rica | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [210] | 2016 | Curacao | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% diarrhea | |||||||||||

| [210] | 2016 | Jamaica | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% abdominal pain, retro orbital pain and vomiting | |||||||||

| [212] | 2016 | Martinique, Brazil and Colombia | 3 | 67% | 33% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 67% | 33% | 33% | |||||||

| [210] | 2016 | Nicaragua | 2 | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||||

| [213] | 2015 | Suriname | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% itchy, painful skin | |||||||||

| [214] | 2016 | Suriname | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% itchy and subcutaneous haematomas on arms and legs (day 10) day 29 diagnosed: immune-mediated thrombocytopenia | ||||||||

| [215] | 2016 | Venezuela | 2 | 100% | 50% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [195] | 2016 | Virgin Islands (US) | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||

| Asia and Australasia | ||||||||||||||||||

| [82] | 2010 | Cambodia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||||

| [216] | 2015 | Cook Islands | 2 | 100% | 100% | 50% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [57] | 2014 | Cook Islands | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [217] | 2014 | Cook Islands | 2 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [218] | 2014 | French Polynesia | 2 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 1/2 slight gingival bleeding for a few days | |||||

| [74] | 2014 | French Polynesia | 2 | 100% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 100% | 50% | 2 cases had co-infection with two different dengue strains. | |||||

| [219] | 2014 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||

| [59] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [220] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||

| [221] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [72] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 3 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 67% | 100% | 33% | 100% | 1/3 aphthous ulcer | |||||||

| [222] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 2 | 50% | 100% | 50% | Pregnant cases had ZIKV infection immediately before or after birth; newborns developed ZIKV (2/2 RT-PCR positive, 1/2 rash) with no complications (one had gestational diabetes) | |||||||||||

| [223] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Developed Guillain-Barré syndrome at day 7 (see complications table) | ||||||||||

| [69] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 2 | 100% | 50% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 50% | |||||||||

| [67] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||

| [224] | 2013 | French Polynesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||

| [53] | 2014–15 | Indonesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| [78] | 2015 | Indonesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||

| [66] | 2012 | Indonesia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||

| [225] | 2014 | Malaysia | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 1/1 burning sensation of palms of hands and soles of feet. 1/1 sudden development of bilateral dull and metallic hearing—left ear a very short delay between a sound and perception of sound, duration 10 days with gradual resolution. | ||||||||

| [58] | 2015 | Maldives | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||

| [226] | 2015 | New Caledonia | 1 | 100% | 100% | Gave birth, 37 wk, at ZIKV onset. | ||||||||||||

| [75] | 2012 | Philippines | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 1/1 stomach pain, anorexia | ||||||||

| [227] | 2014 | Thailand | 2 | 50% | 100% | 50% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 50% diffuse pain | ||||||||

| [228] | 2016 | Thailand | 1 | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||||

| [229] | 2014 | Thailand | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||||

| [60] | 2013 | Thailand | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 1/1 chills, 1/1 mouth blisters (appeared after 2 days); symptomatic for 16 days | ||||||||

| [230] | 2013 | Thailand | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||||||||

| Africa | ||||||||||||||||||

| [127] | 1971 | Nigeria | 2 | 100% | 50% | 50% | ||||||||||||

| [88] | 1956 | Nigeria | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | Laboratory challenge of human volunteer | |||||||||||

| [43] | 1952 | Nigeria | 3 | 100% | 67% | 67% | 33% | 33% | 1/3 jaundice (but concurrent epidemic of jaundice), 1/3 albumin in the urine on day 3–5. | |||||||||

| [231] | 2008 | Senegal | 3 | 100% | 100% | 33% | 67% | 100% | 66% | 33% | 66% | 50% | 2/3 chills, 1/3 prostatitis, 2/3 aphthous ulcers on lip (day 4), 1/3 photophobia, 2/3 reported arthralgia reoccurring for several months. | |||||

| [232] | 1962 | Uganda | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||||||

| Europe | ||||||||||||||||||

| [233] | 1973 | Portugal | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | Laboratory acquired ZIKV: 1/1/ chills, 1/1 sweating | |||||||||||

| Symptom Frequency across case studies | 84% | 57% | 79% | 54% | 43% | 41% | 13% | 16% | 10% | 22% | 28% | 11% | 7% | 3% | ||||

| Symptom Frequency across Observational studies | 66% | 54% | 85% | 41% | 45% | 31% | 15% | 13% | 5% | 14% | 5% | 3% | 12% | 1% | ||||

Fever (typically reported as low grade 38–40 C lasting usually 2–4 days, range 1–8 days).

Joint pain (usually wrist, fingers, ankles or knees affected, some reports of low back pain. Pain lasts typically less than a week, but there are reports of intermittent arthralgia for 1–2 months).

Rash (common description: diffuse pink maculopapular rash which covered the face, neck, trunk and upper arms, occasionally this is reported as "itchy", typically appeared around day 2 of illness and faded around day 5, although there are cases where the rash lasted up to 2 weeks.).

Conjunctivitis (red eyes)—mostly reported to occur in both eyes.

Muscle pain (reported to range from mild to severe and last 2–7 days).

Headache (mild headache often the first symptom and is reported to last 2–4 days).

Retro-orbital pain. Edema (usually in hands/fingers or ankles/feet) duration approximately 7 days.).

Lymphadenopathy—duration up to 2 weeks. Often reported in cervical area.

Malaise 2–14 days.

Asthenia—2 to 14 days and often preceded rash by up to 48 hours.

Sore throat/cough (duration 4 days).

Nausea/vomiting/ diarrhea.

Hematospermia (occurred at day 5 to 14 after symptoms appeared)

Table 11. Complications reported to be associated with ZIKV infection in 35 case reports/ case series and outbreak reports.

20 reports on birth defects and microcephaly in pregnant women (2013–2016) and 24 on Guillain-Barré syndrome following ZIKV infection (probable and confirmed) during outbreaks in the Pacific Islands and the Americas (2011–2016).

| Ref | Country | Study year | Complication | N | ZIKV confirmed? | Description of clinical findings: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcephaly and other birth defects potentially associated with ZIKV infection | ||||||

| [148] | French Polynesia | 2014 | Birth Defects: fetal cerebral anomaly | 18 | 4/6 amniotic fluid samples were RT-PCR positive | French Polynesia has ~4000 births/year. Retrospective analysis of birth defects involving the central nervous system indicated 18 cases in 2014 (vs. 4 in 2013 and 3 in 2012) where the mothers may have been infected with ZIKV early in pregnancy. Amniotic fluid samples from standard testing procedures showed 4/6 samples were ZIKV positive. Since our search, an additional paper on this set of cases has been published. |

| [206] | Brazil | 2015 | Birth defects: microcephaly | 3 | 33% mothers had clinical symptoms. No testing done. | CT scan and ocular examination showed all infants had unilateral ocular findings: gross macular pigment mottling and foveal reflex loss. Well-defined macular neuroretinal atrophy was detected in one child. |

| [80] | Brazil | 2015 | Birth defects: microcephaly | 8 | 25% positive amniotic fluid, 75% mothers had clinical symptoms during pregnancy | Amniotic fluid positive fetuses (n = 2), note mother’s serum RT-PCR1 was negative: both eyes had cataracts and intraocular calcifications, and one eye was smaller than the other. Fetuses from mothers with clinical symptoms (n = 6): fetal neurosonograms showed 33% cases with cerebellar involvement and 16% with severe arthrogryposis. |

| [201] | Brazil | 2015 | Birth defects: Microcephaly and ocular defects | 29 | 29 cases | 29 infants age 1–6 months. 23/29 mothers had clinical ZIKV infections: 18/29 first trimester, 4/29 second trimester, 1/29 third trimester. 6 had no symptoms of ZIKV; 10 patients had ocular findings and were presumed to have been exposed to ZIKV. |

| [52] | Brazil | 2015 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 2 | 2 cases: first and second trimester ZIKV infections | Case 1: normal ultrasound at 16wk, ZIKV at 18wk, ultrasound at 21 weeks detected microcephaly, confirmed at 27wk. Baby born at 40wks with head circumference of 30cm. Case 2: ZIKV at 10wk, 22wk ultrasound indicated fetal head <10th percentile, 25wk indicated microcephaly, term delivery neonate presented with severe ventriculomegaly, microphthalmia, cataract, and severe arthrogryposis in the legs and arms. Amniotic fluid positive at 28wks. |

| [55] | Brazil | 2015/10 | Microcephaly | 1 | RT-PCR positive on fetal brain sample | Mother had ZIKV at 13 weeks gestation. Ultrasound at 14 and 20 weeks were normal. Ultrasound at 29 and 32 weeks showed retardation of growth with normal amniotic fluid and placenta, a head circumference below the second percentile for gestation (microcephaly), moderate ventriculomegaly. Brain structures were blurred, calcifications and no other fetal structural abnormalities. Fetal, umbilical, and uterine blood flows were normal. RT-PCR1 ZIKV positive in the fetal brain sample (6.5×107 viral RNA copies per milligram of tissue). |

| [202] | Brazil | 2015/12 | Birth defects: Microcephaly and ocular findings | 10 | 10 cases | 10 cases had clinical diagnosis of ZIKV vertical infection (mothers 7/10 rash, 6 in 1st trimester) and diagnosed with ophthalmological abnormalities |

| [234] | Brazil | 2015/08–2015/10 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 35 | 35 cases. 25/35 severe microcephaly, 17/35 at least one neurologic abnormality. | 26/35 mothers recalled a rash during pregnancy: first trimester 21/26 and 5/26 in the second trimester. Pathology: Computed tomography scans and transfontanellar cranial ultrasounds showed a consistent pattern of widespread brain calcifications, ventricular enlargement secondary to cortical/subcortical atrophy, excessive and redundant scalp skin in 11 (31%) cases, also suggests acute intrauterine brain injury, indicating an arrest in cerebral growth. |

| [235] | Brazil | up to 2015/11/21 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 739 | 739 cases (1 death) | Nov 7, 2015: case definition revised from <33cm to <32cm. |

| [4,172] | Brazil | up to 2015/11/30 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 1248 | 1,248 cases (7 deaths) | 1,248 cases equates to 99.7/100,000 live births have microcephaly. Brazil noted many affected women appear to have been infected with ZIKV in first trimester (no data) |

| [236] | Brazil | up to 2015/12/05 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 1761 | 1761 cases (19 deaths) | |

| [170, 237] | Brazil | up to 2016/01/31 | Birth defects: Microcephaly or CNS malformation | 4783 | 4783 cases (76 deaths) | 5/76 deaths were ZIKV positive. Historic average 163/year. |

| [116,117,238] | Brazil | 2015/11–2016/02/13 | Birth defects: Microcephaly or other CNS involvement | 5280 | 5280 cases (108 deaths) | Brazil 2001 to 2014 had an average of 163 microcephaly cases/year. Validation of 1345 cases of microcephaly is complete: 837 discarded, 508 confirmed by 421/462 cases radiological findings and 41/462 ZIKV confirmed infection. |

| [48] | Brazil | 2016 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 1 | 1 case | 20 year old mother: microcephaly detection at 18 weeks, pregnancy terminated at 32 weeks. Fetal tissues: cerebral cortex, medulla oblongata and cerebrospinal and amniotic fluid ZIKV RT-PCR positive. |

| [116, 239] | Hawaii | 2016/01/08 | Birth defects: Microcephaly | 1 | Case of microcephaly, confirmed ZIKV | The mother likely acquired ZIKV in Brazil (May 2015) and her newborn acquired the infection in utero. |

| [240] | USA | 2015/08/01–2016/02/07 | Birth defects: Microcephaly, miscarriage | 9 | 3/9 fetuses ZIKV positive.9/9 mothers ZIKV confirmed. | 1st trimester (6/9): 2 miscarriages, 2 terminations, 1 microcephaly case, one not born yet. Trimester 3 (3/9): 3 apparently healthy infants. Travel to American Samoa, Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Puerto Rico. In USA 151/257 pregnancies tested for ZIKV, 8 IgM positive. |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) or other neurological complications potentially associated with ZIKV infection | ||||||

| [116, 117, 170, 172,241,242] | Brazil | 2015/11 | GBS | 7 | 7/10 GBS patients were ZIKV positive | 1708 GBS cases (2015) vs. 1439 cases (2014). |

| [4,116, 117,170,172,237,242] | Brazil | 2015/05/01–2015/07/13 | GBS | 42 | 62% (26/42) were ZIKV positive | |

| [173] | Brazil | 2015/02/15-2015/06/25 | GBS | 24 | 24 cases of suspect GBS were reported during an outbreak of 14,835 cases of “indeterminate acute exanthematous illness” in Salvador, Brazil (3rd largest city). Confirmation tests not done for ZIKV, chikungunya or dengue. | |

| [116,117, 175,237] | Colombia | 2015/12/27–2016/01/31 | GBS | 86 | 86 cases in 2 months | Historic average is 242 GBS /year (20 cases /month). |

| [117,178,237,242, 243] | El Salvador | 2015/12–2016/01/09 | GBS | 46 | 46–118 GBS cases in 5 weeks (2 deaths) | 2014 average was 169 cases/year. Case series 12/22 GBS patients had ZIKV within the 15 days prior to GBS. |

| [116,117,137,138, 144–147, 172,242,244,245] | French Polynesia | Nov 2013-Feb 2014 | GBS | 42 | 42 cases of GBS and increased incidence of neurological complications were reported associated with the ZIKV outbreak in the Pacific Islands. 37/42 GBS cases reported having a viral syndrome 6 (4–10) days before the onset of GBS. GBS symptoms peaked at 6 (4–9) days and by 3 months after discharge, 24 (57%) patients were able to walk without assistance. All GBS patients were hospitalized, median 11days (7–20) (N = 42) and 51 days (16–70) for ICU patients (n = 10).Symptoms: Clinical presentation at hospital admission included generalised muscle weakness (74%), inability to walk (44%), facial palsy (64%), 39 (93%) patients had increased (>0·52 g/L) protein concentration in their CSF, 16 (38%) patients were admitted to ICU and 12 (29%) required respiratory assistance. All cases (100%) received immunoglobulin treatment and one (2%) had plasmapheresis. | |

| [245] | French Polynesia | Nov 2013-Feb 2014 | GBS | 42 | Case control study: | If the ZIKV attack rate in French Polynesia was 66%, the risk of GBS was 0·24/1000 Zika virus infections. Patient and control samples drawn at several time points were examined by RT-PCR, IgM / IgG and PRNT2 reaction. 98% of GBS patients were IgM or IgG positive, 19% cross-reacted with dengue, but 100% were confirmed ZIKV positive by PRNT. Compared to a control group of hospitalized patients, the odds of a GBS patient being ZIKV positive was 59·7 (95% CI 10·4 –+∞); p<0·0001. And for PRNT the odds was 34·1 (95% CI 5·8 –+∞) p<0·0001. No association was detected for dengue test results and GBS. |

| [223] | French Polynesia | 2013 | GBS | 1 | Case report, sero-positive | Polynesian woman, early 40s had ZIKV symptoms 7 days before neurological symptoms. No past medical history except acute articular rheumatism. Day 0: evaluated for paraesthesia of the four limb extremities. Day 1: admitted to hospital, paraesthesia had evolved into ascendant muscular weakness suggestive of GBS. Day 3: developed tetraparesis predominant in the lower limbs, with paraesthesia of the extremities, diffuse myalgia, and a bilateral, but asymmetric peripheral facial palsy. Deep tendon reflexes absent. No respiratory or deglutition disorders. Chest pain developed related to a sustained ventricular tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension, both suggestive of dysautonomia. Electromyogram confirmed a diffuse demyelinating disorder, with elevated distal motor latency, elongated F-wave, conduction block and acute denervation, without axonal abnormalities. Day 13: discharged with paraparesis requiring the use of a walking frame, and the facial palsy slowly disappeared. Day 40, able to walk without help and muscular strength score was 85/100. |

| [181, 237] | Martinique | 2016/01/21 | GBS | 6 | 6/6 GBS cases were ZIKV positive | |

| [246] | New Caledonia | 2011/01/01–2014/12/31 | GBS | 42 | 42 cases of GBS between 2011–2014 investigated. | 42 cases of GBS: incidence 2011 = 2.6 (0.66–4.54)/100000 vs. 2014 = 5.09 (2/49-7.56)/100000 = NOT a significant difference. 13 (30%) cases occurred between March and July 2014 (during ZIKV outbreak), 6 in April 2014. These patients indicated 2 confirmed and 2 suspect ZIKV cases and 4 dengue cases preceded GBS. |

| [189] | Puerto Rico | 2015/11/23-2016/01/28 | GBS | 1 | 1 ZIKV positive case developed GBS | |

| [116, 117,170] | Suriname | 2015/12–2016/01/21 | GBS | 13 | 10 GBS (2015) and 3 GBS (2016) | Historic average is 4/year. 2/10 2015 cases were ZIKV confirmed. |

| [214] | Suriname | 2016/01 | immune-mediated thrombocytopenia | 1 | ZIKV positive patient | Developed normal clinical symptoms of ZIKV, and on day 29 diagnosed immune-mediated thrombocytopenia. |

| [117, 170,175,237] | Venezuela | 2016/01/01–2016/02/10 | GBS and other neurological symptoms | 252 | 252 GBS (3 confirmed) | Up to 76% of patients reported clinical symptoms of ZIKV. 65% had comorbidities. 3 cases with other neurological symptoms were ZIKV positive. |

1 RT-PCR = reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction,

2 PRNT = plaque reduction neutralization test

Complications associated with ZIKV infection in humans are reported in Table 11. The research and attention concentrated on all potential complications of ZIKV has increased significantly in the last few months; we identified that many official reports and papers published the same information multiple times. A number of small case series or case studies investigating complications with ZIKV have demonstrated a chronological association between ZIKV infection in pregnant women and development of microcephaly in the fetus, ZIKV infection in fetuses and newborns from mothers exposed to ZIKV at various points during pregnancy, and ZIKV preceding neurological conditions, mainly Guillain-Barre syndrome in adults, Table 11. A significant increase in microcephaly has been reported in Brazil and a good deal of research and scrutiny of the existing data is on-going to determine the degree that ZIKV is contributing to microcephaly cases. Two studies discuss the criteria used to categorize infants as positive for microcephaly and the potential impact on the numbers reported in Brazil [247,248]; one study shows evidence of an increase in microcephaly in Brazil starting in 2012 prior to ZIKV arriving in the Americas [248]. Other birth defects have also been noted including a number of ocular abnormalities and hydrops fetalis [48,201]. Hopefully on-going cohort studies will provide better evidence for the role ZIKV plays in birth defects and fetal death. Outside of Brazil, no other country has noted the increase in microcephaly at the time of writing (March 1, 2016), however several countries in the Americas and Australasia have noted an increase in Guillain-Barré Syndrome coinciding with a ZIKV outbreak, Table 11 [146,242,246].

Transmission

ZIKV is known to be transmitted by mosquitos; however there is also increasing evidence that intrauterine transmission and sexual transmission via semen may occur, Table 12. It has also been suggested that transmission by blood transfusion is possible, although no cases have been reported [71]. Two studies examined the efficacy of amotosalen combined with UVA light treatment of plasma and recommended that it was effective to deactivate ZIKV [30,32].

Table 12. Studies reporting various modes of human to human transmission and one human to mosquito transmission study.

| Refid | Year of study | Country | Study design | Mode of transmission | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [80] | 2015 | Brazil | Case study | human- intrauterine | 2 mothers with clinical symptoms of ZIKV were serum negative, but amniotic fluid positive. |

| [116] | 2016 | Brazil | Outbreak investigation | human- intrauterine | 17 infants with microcephaly and 5 fetuses were ZIKV positive |