Abstract

Purpose

Preliminary investigation of a fucoidan with demonstrated reduction in the symptoms of osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip and knee.

Patients and methods

A double-blind randomized controlled trial was carried out to determine the safety and efficacy of a 300 mg dose of a Fucus vesiculosus extract (85% fucoidan) over a 12-week period in a population (n=122) with mild-to-moderate OA of the hip and knee as measured by the validated instrument “Comprehensive Osteoarthritis Test.” Safety was measured by assessing cholesterol, liver function, renal function, and hematopoietic function, and closely monitoring adverse events.

Result

Ninety-six participants completed the study. The reduction in symptoms of OA was not significantly different from the placebo response. There were no changes in the blood measurements that were of any clinical significance during the course of the study.

Conclusion

The F. vesiculosus fucoidan extract was safe and well tolerated. At a dose of 300 mg, the extract showed no difference in reduction of OA symptoms from the placebo.

Keywords: joint pain, clinical trial, seaweed, polysaccharide

Introduction

Fucus vesiculosus (Linnaeus, 1753)1 is a northern hemisphere algal species found in intertidal zones, commonly known as “bladderwrack”. It is one of the marine algae that has been used historically as an herbal medicine to address a variety of complaints, including sore joints, obesity, and fatigue.2 It continues to be used today as a dried herb or as an aqueous alcohol tincture in a number of health supplements available throughout the world. It is considered edible and is consumed as a medicinal food, but ingestion must be limited to ensure a safe level of iodine intake. In a previous trial, a randomized study using either 100 mg or 1,000 mg of a fucoidan-rich seaweed extract blend was carried out on subjects with osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. The main component of the extract was 85% F. vesiculosus fucoidan. The trial participants were assessed using the Comprehensive Osteoarthritis Test (COAT) assessment instrument3 over a 12-week trial. The trial had a high level of compliance (>95%), and the preparation was proven safe to use. The study demonstrated clear dose dependence. The participants showed a 52% improvement in COAT scores at a dose of 1,000 mg of fucoidan and 18% on a dose of 100 mg. The 1,000 mg dose delivered an effect comparable to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.4

F. vesiculosus, in common with other brown macroalgae, contains high levels of polysaccharides, including the gelling type (alginates) and the nongelling, sulfated, fucose-rich “fucoidan.” Fucoidan as an isolated component is used as an ingredient in nutraceuticals, particularly in Asia, where it is considered to be an immune support taken during illness and concomitant with conventional therapies. Fucoidan has been shown to be effective at reducing fatigue associated with chemotherapy.5 Fucoidans from various species have been assessed for biological activity in a broad range of applications.6 They are potent antiviral agents7,8 that modulate immune responses,9 attenuate inflammation,10 and have some anticancer effects in vitro11,12 and in animal models.13

OA is a common, slowly progressive joint condition that causes significant disability in the adult population. The prevalence of the condition increases with age, with established risk factors including obesity, local trauma, and occupation. Severe radiographic changes of knee OA are found in 1% of adults of 25–34 years of age and increase to ~50% in adults aged 75 years and older. OA of the hips and knees results in the greatest burden to the adult population. The pain and stiffness in these large weight-bearing joints often cause significant disability, leading to the inability to undertake the normal activities of daily life, and in severe cases, require joint replacement surgery.14

The objective of this study was to establish the efficacy and safety of F. vesiculosus in a randomized placebo-controlled trial using a F. vesiculosus extract (85% fucoidan) at a dose of 300 mg daily for 12 weeks.

Material and methods

Design

This trial was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study conducted in 2011 over 12 weeks (84 days) by a single research group in five centers (Lismore, Ballina, Byron Bay, Coffs Harbour, and Tweed Heads) in New South Wales, Australia. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Southern Cross University (ethics approval number: ECN-11-129). The research was conducted in compliance with good clinical practices and in accordance with the guidelines of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2004). The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN 12613000654752).

Participants

Otherwise healthy volunteers aged between 25 years and 65 years were recruited from Southern Cross University, Lismore, Ballina, Byron Bay, Tweed Heads, Coffs Harbour and surrounding districts through newspaper advertising, regional radio, and television. All participants signed an informed consent form after they were selected and given additional information about the study. Each participant with more than one joint affected by OA was asked to nominate a target joint that they would follow through the course of the study. It was requested that all measurements related to the nominated target joint. Inclusion criteria included good general health and X-ray and clinical evidence of OA in either the hip or knee joint. Exclusion criteria included a history of trauma associated with the affected joint; rheumatoid or other inflammatory joint conditions; gout; use of corticosteroids (intra-articular or systemic) within 4 weeks prior to baseline and throughout the study; use of anti-inflammatory agents or antiarthritic complementary medicines 3 weeks prior to baseline and for the duration of the study; liver function tests greater than three times the upper limit of normal at baseline; a history of alcohol or substance abuse; female participants who are lactating, pregnant, or planning to become pregnant; participants who have participated in another clinical trial in the last 30 days; participants unwilling to comply with the study protocol; and any other condition that in the opinion of the investigators could compromise the study.

Baseline COAT measures were recorded, and participants with combined visual analog scale scores between 3 and 7 (determined as mild-to-moderate OA) who agreed to wash out from their current OA treatment were admitted to the study. Wash out commenced at 4 weeks prior to baseline, and participants ceased all nonstudy OA medications such as Ibuprofen, Brufen, Mobic, Celebrex, Voltaren, and Naprosyn as well as natural and complementary medicines such as glucosamine or celery for the duration of the study. The participants were supplied with study diaries and asked to record their COAT scores and paracetamol (acetaminophen) use daily for 4 weeks. They were requested not to take narcotic analgesics and those containing codeine for 7 days before the next clinic and until the end of the study. They returned every 4 weeks to renew medication and for assessment. Study staff contacted the participants daily to ensure compliance and provide support.

Study medication and dose

The study medication was provided by Marinova Pty Ltd, Cambridge, Australia. Marinova is certified according to the International Organization for Standardization’s standard for Quality Management Systems, ISO 9001:2015. All products are made in accordance to the food-safety principles of hazard analysis and critical control points in a facility adherent with good manufacturing practices. All of Marinova’s products are certified organic, Kosher and Halal. The extract was a fucoidan-rich extract of F. vesiculosus, manufactured using a proprietary aqueous process. Insoluble matter and salts were removed during the process. The extract was a “whole plant extract” that contained plant polyphenols in addition to the fucoidan. The concentration of the fucoidan in the extract was 88.5% w/w. The remainder comprised 7.4% polyphenol, as determined by Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 4.1% alginate. The study medication was prepared as capsules containing 150 mg of extract per capsule. Each capsule weighed 352 mg, the balance of which was microcrystalline cellulose. The placebo capsules also weighed 352 mg and were composed of microcrystalline cellulose. Capsules were self-administered twice a day (morning and evening) by the participants.

Marinova Pty Ltd provided the study medication, and each container was labeled with the participant identification code and study dose. The label also carried the warning “keep out of reach of children.” The study medication was returned at the end of each study period, and tablets were counted as an indicator of compliance. No medication was available to people who were not enrolled in the study.

Randomization and blinding were achieved by random sequence generator of each subject into either placebo or active. The trial was not unblinded until all the data were collected, and the sequence was revealed to the researchers.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measurements in this study were the average daily COAT score for efficacy and adverse events for safety. COAT is a validated measurement instrument for the assessment of the symptoms of OA, which generates a score composed of four different subscales: pain, stiffness, difficulty with physical activity, and overall symptom severity.3

Secondary outcome measurements included COAT measurement taken at the clinics (baseline; weeks 4, 8, and 12), paracetamol usage (participants recorded paracetamol usage on a daily basis in a study diary), and body mass index (BMI; baseline; weeks 4, 8, and 12). In addition, blood was taken at baseline and week 12.

Blood tests

Blood samples were drawn to determine full blood count; liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase, serum alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma glutamyl transferase, bilirubin); serum urea, electrolytes, and creatinine; and biomarkers (C-reactive protein [CRP], interleukin 6 [IL-6], and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-alpha levels). The blood safety markers provide data on the toxicity to the hematopoietic, hepatic, and renal systems.

After collection, serum was stored at −80°C until analyzed. Serum TNF-alpha and IL-6 were measured using a high sensitivity sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), while CRP was measured using an instant ELISA (Bender MedSystems GmbH, Vienna, Austria). All samples were assayed in duplicate as per the kit instructions.

Statistical analysis

COAT scores

Scatter plots of COAT scores by day with fitted Lowess curves were employed to display the mean response profiles. The linear mixed effects model was fitted to the daily COAT scores with fixed factors for joint (knee, hip) and treatment (treatment A, treatment B), and three linear functions of day (F1 for day 1–day 28, F2 for day 29–day 56, and F3 for day 57–day 84). Random effects were the patient (variation at day 1) and day within patient (residual variation). The repeated measures on patients over days (residuals) were modeled with an AR1 autoregressive structure. A full-factorial model was fitted that included all main effects, all two-way interaction effects, and all three-way interaction effects. The model was systematically reduced to eliminate nonsignificant higher order interaction effects and main effects. Estimates were obtained by the method of residual maximum likelihood, and the model was fitted using the SPSS Version 19 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) mixed procedure (Tables S1 and S2).

Compliance

Compliance was measured from tablet counts. Each subject was issued with a bottle of tablets that contained a known overage of tablets at baseline, week 4, and week 8 and asked to return the bottles at the next clinic. Tablets not taken in excess of the known total dosage were deemed to contribute to noncompliance. Noncompliance was defined a priori as <85% of study medication consumed. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for differences between treatment over time was undertaken for each of three periods of 4 weeks. Post hoc tests were used to test significant interaction effects (Table S3).

Demographics

Chi-squared tests of association for categorical variables and independent t-test for continuous variables were used to determine differences between the two treatment groups based on demographic (age, sex, joint) and lifestyle variables (BMI, smoking, exercise, alcohol use) at baseline.

Paracetamol usage

Independent t-test was used to assess treatment differences for total paracetamol usage over the 12 weeks. Owing to the skewed distribution of this measure, a logarithmic (base 10) transformation log(x+1) was used for the multilevel repeated measures ANOVA, which was used to assess the pattern of weekly paracetamol usage by treatment. The model components included time, treatment, and treatment by time interaction effects.

CRP, IL-6, TNF-alpha

Repeated measures ANOVA for baseline and at completion (week 12) was used to assess the effects of time, treatment, and time by treatment interactions for the secondary outcomes of CRP, IL-6, and TNF-alpha. Owing to the inherent skewness of IL-6, logarithmic (base 10) transformed scores were also investigated (Tables S4 and S5).

BMI

Independent t-test was used to assess treatment differences for baseline BMI. Multilevel repeated measures ANOVA was conducted over the four time periods in which BMI was measured. The model components included time, treatment, and treatment by time interaction effects.

Blood safety: hematology and biochemical markers

Repeated measures ANOVA for baseline and at completion (week 12) was used to assess the effects of time, treatment, and time by treatment interactions for hematology and biochemical blood safety measures, where a significant interaction effect would indicate differences between treatments over time.

Adverse events

Cross-tabulations and chi-squared tests of association with Fisher’s exact test were used to compare and assess the occurrence of adverse events, both in each of the three 4-week periods of the study and over the study as a whole.

Results

Study population

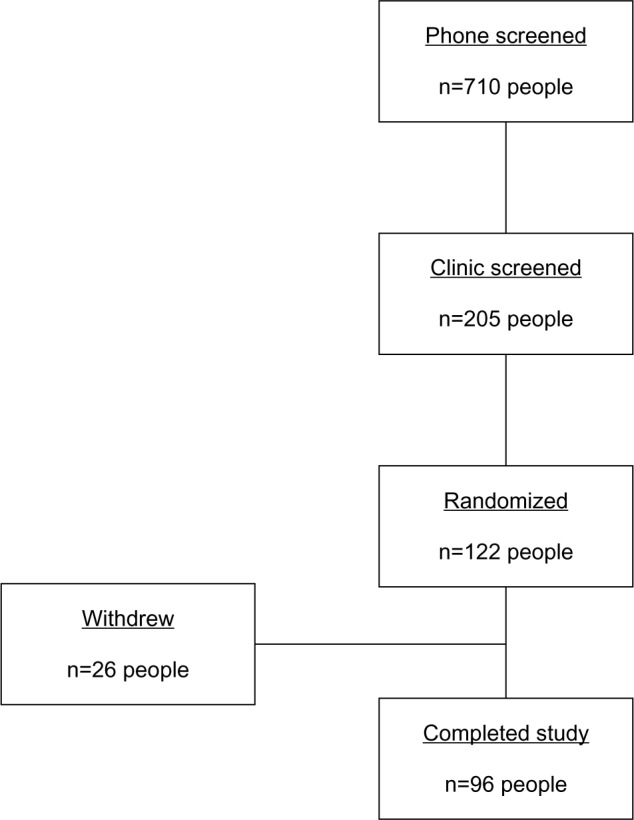

The study screened volunteers and subsequently enrolled them if they met the criteria. In total, 710 people were screened by telephone interview; of these, 205 were invited to the screening clinical visit. This resulted in 122 subjects being randomized to either active or placebo treatments and 96 completed the study, as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of trial process.

The participants who completed the study comprised 40 females and 56 males. The mean age of the study group participants was 62.0 years (SD =10.4), ranging from 25 years to 84 years; BMI ranged from 18 to 48 (mean BMI=28.7, SD =4.9).

The majority of participants (n=62) were diagnosed with OA in the knee in comparison with OA of the hip (n=34). Table 1 provides the distribution of participants in both arms of the study by joint. The large percentage (89%) did some form of exercise. The majority of participants were nonsmokers (97%) but consumed alcohol (85%). Sex distribution, mean age, mean BMI, affected joints, exercise, smoking status, and alcohol consumption did not differ significantly by treatment (P>0.05).

Table 1.

Number of patients allocated to each treatment by joint

| Joint | Placebo | Active | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knee | 28 | 34 | 62 |

| Hip | 14 | 20 | 34 |

COAT score

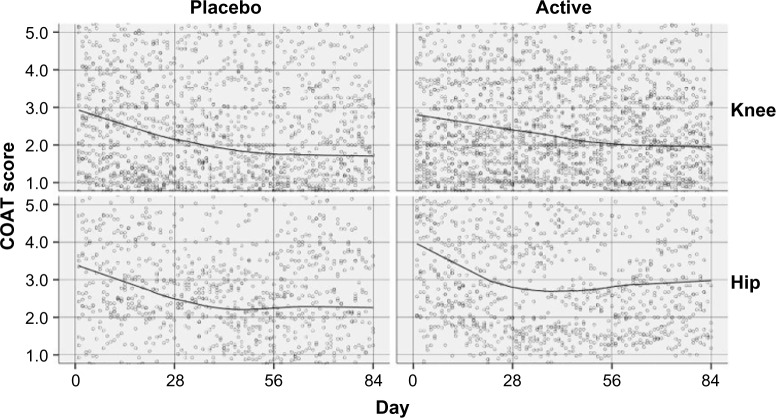

Subjects taking either the active or the placebo experienced a reduction in the average COAT score for both the hip and knee joints over the period of the study. The primary outcome measure was the average daily diary COAT score, calculated as the mean of the pain, stiffness, physical, and overall subscale scores. Factors of interest were the target joint (knee or hip), the treatment (active or placebo), and the change over time (84 days of measurements). Scatter plots of COAT scores are shown in Figure 2 for each treatment and joint.

Figure 2.

Average COAT score by day for each treatment and joint for full participants (n=96) with fitted Lowess curves.

Abbreviation: COAT, Comprehensive Osteoarthritis Test.

The response curves shown in Figure 2 could be well approximated by three linear pieces: from day 1 to day 28, from day 29 to day 56, and from day 57 to day 84. The full details of this analysis are included in the Supplementary materials.

The overall difference (day 1–day 84) in response slopes between placebo and active for the knee joint was nonsignificant with an estimate =0.00118 per day, SE =0.00577, and P=0.838. In addition, there were no significant (P<0.05) differences between treatments on COAT-scale mean scores for the knee joint at any of day 1, day 28, day 56, or day 84. The overall difference (day 1–day 84) in response slopes between placebo and active for the hip joint was nonsignificant with an estimate =0.00062 per day, SE =0.00798, and P=0.938. In addition, there were no significant (P<0.05) differences between treatments on COAT scale mean scores for the hip joint at any of day 1, day 28, day 56, or day 84.

Compliance

Results of repeated measures ANOVA for differences between treatment over time showed no significant treatment (P=0.253) or treatment by time interaction (P=0.635) effects; however, there was a significant decline over time (P=0.001) with estimated means for each 4-week period presented.

Paracetamol usage

There was no significant difference in paracetamol usage between active or placebo treatments for any of the weeks (P>0.05).

CRP, IL-6, log(IL-6), TNF-alpha

The repeated measures analysis indicated that there was a difference between treatments over time for IL-6 and log(IL-6) as evident by the significant treatment by time interaction for both the original and transformed scores (P=0.004 for both). Placebo decreased on average by 0.4 pg/mL and active increased by a similar amount. There were no significant differences for any measurement of CRP or TNF-alpha.

BMI

A multilevel repeated measures analysis with autocorrelated time was conducted over the four time periods where BMI was measured (baseline; weeks 4, 8, and 12). The model included time, treatment, and the treatment by time interaction, where the effect of treatment was nonsignificant (P=0.738), but the effect over time (P=0.002) and the treatment by time interaction (P=0.040) were significant.

The post hoc analysis showed a significant increase in BMI over time for all participants, with weeks 4 and 8 being significantly higher than baseline means. For the significant treatment by time interaction, there was no significant difference in BMI between treatments for any of the times (P>0.05). However, the median BMI increased by approximately one unit (Table S6) for the placebo group and 0.1 of a unit for the active group. The significant treatment by time interaction indicated that the pattern over time was different for the placebo and active treatment groups, which is illustrated in Tables S7 and S8. The estimated BMI increased at each time point in the placebo group (all 4-, 8-, 12-week times were significantly higher than baseline), but the active group showed no significant difference at any time points from the baseline score with respect to BMI.

Safety measures

There were no significant treatment by time interactions with any of the hematology or biochemistry measures. However, significant decreases over time were evident for red cell count, hemoglobin, hemacrit, mean corpuscular volume, platelets, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, protein, and potassium, as well as significant increases over time for monocytes, albumin, sodium, and chloride. However, these changes were not considered clinically significant (Tables S4, S5, S9 and S10).

Adverse events

The results of Fisher’s exact tests of associations with cross-tabulation showed that there was no difference in the frequency of adverse events between the two treatments at any of the four weekly intervals or over the complete period (P>0.05) (Table S11).

Withdrawals

Twenty-six participants withdrew from the study. The reasons for withdrawal included pain (14 participants, of which nine were in the placebo arm), noncompliance (five participants), and other reasons (six participants – three due to inability to attend due to work commitments, two due to diarrhea, and one due to nausea). One subject withdrew due to a serious adverse event, a cardiac event not considered to be related to the study medication.

Discussion

A key feature of the results obtained in this trial was the lack of difference between the active and placebo treatments. There was a 30.6% reduction in COAT score for the knee joint for subjects taking placebo as compared to a 29% reduction for subjects taking the active. The results obtained for COAT correlated well with the results obtained for WOMAC. Other published trials have also observed strong placebo responses in OA studies. In the GAIT study, subjects on the drug celecoxib achieved a reduction on the WOMAC OA scale of 70.1% and the subjects taking placebo achieved a reduction of 60.1% at 6 months.15 There appears to be a high placebo effect in OA trials generally.16 Excellent clinical care is a strong inducer of placebo response.

Participants administered the seaweed extract over a period of 12 weeks experienced no clinically significant change in blood safety markers or any adverse events specifically associated with the trial medication. Participants taking placebo exhibited significantly increased BMI at each time point (4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks), while participants administered the seaweed extract showed no significant difference at any time points from the baseline score. The seaweed extract at 300 mg per day was demonstrated to be safe over the 12-week study period.

In our earlier combined Phase I and Phase II open-label study,4 we found strong evidence for a dose-dependent effect between mild symptom relief (18%) at 100 mg and marked symptom relief (52%) at 1,000 mg of a combined seaweed extract preparation (85% F. vesiculosus fucoidan). It was on the basis of this preliminary trial that it was determined to test 85% F. vesiculosus fucoidan at a 300 mg dosage. On the basis of a 30% placebo effect, a higher dose is required as a beneficial treatment for OA. Additionally, the earlier study used a complex that included vitamin B6, zinc, and manganese. There may be synergistic effects associated with these nutrients that were not replicated in this study.

The polyphenols contained in F. vesiculosus, present only at low concentrations in the fucoidan used in this study, have been characterized by others.17 While they possess antioxidant and other biological activities, they were assumed not to be present in sufficient quantity to exert any clinically observable effects.

Sufferers of OA show increased levels of TNF-alpha.18 CRP is also associated with inflammation and OA.19 We hypothesized that this marker would be decreased by ingestion of the F. vesiculosus extract. The inflammation biomarkers CRP and TNF-alpha included in the study were not changed in either placebo or active groups. Similarly, in the earlier study, there was no change in TNF-alpha despite the reduction in symptoms experienced by the subjects. This illustrates that there is no systemic effect of the extract on the expression of CRP or TNF-alpha. Thus, any reduction in symptoms was not associated with a reduction in the TNF-alpha cascade or in CRP. In an earlier study, a small decrease in IL-6 was noted in healthy subjects (not OA subjects).20 However, this was not confirmed in this current larger study of OA sufferers, which showed a small increase in IL-6 in the active group and a small decrease in the placebo group.

The mechanism for the previously observed reduction in OA symptoms by fucoidan is unclear. Fucoidan is a known active selectin blocker. Selectin blockade can reduce post ischemic inflammatory cascades and prevent inflammatory damage in a variety of animal models.6 Uptake is low, but observed for fucoidan from two different species.21,22 This may be a mechanism for any observed reduction in symptoms. Additionally, fucoidan is known to mobilize CD34+ stem cell lineages,23,24 while a recent animal study illustrated orally administered fucoidan utility in a cartilage repair model.25 Orally delivered fucoidan can also act as an anti-thrombotic putatively via stimulation of peroxide by intestinal cells exposed to the fucoidan and an increase in prostacyclin, an inhibitor of platelet aggregation.26 OA is associated with vascular pathologies,27,28 and thus, fucoidan may act via this mechanism, when delivered in sufficient quantities.

Conclusion

The fucoidan-rich F. vesiculosus extract was safe and well tolerated. A 300 mg daily dose resulted in 29% improvement (knee). There was no significant difference, however, between active and placebo arm results in the primary outcomes. The elevated rates of response to placebo have also been reported in other OA trials. Further studies should concentrate on increased dose levels.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participants who made this study possible, and the funding made available by the Australian government and by Marinova Pty Ltd.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The study was sponsored by Marinova Pty Ltd under contract to Southern Cross University and performed independently by NatMed-Research. Dr Fitton is employed by Marinova Pty Ltd. While she was involved in the study design, interpretation of results, and preparation of the manuscript, she had no interaction with any study participant, nor was she involved in the day-to-day running or management of the clinical trial. Marinova Pty Ltd paid the article-processing charge associated with the publication of this paper. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Silberfeld T, Rousseau F, de Reviers B. An updated classification of brown algae (Ochrophyta, Phaeophyceae) Cryptogamie Algol. 2014;35(2):117–156. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitton JH, Irhimeh MR, Teas J. Marine algae and polysaccharides with therapeutic applications. In: Barrow C, Shahidi F, editors. Marine Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2008. pp. 345–366. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks LO, Rolfe MI, Cheras PA, Myers SP. The comprehensive osteoarthritis test: a simple index for measurement of treatment effects in clinical trials. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(6):1180–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers SP, O’Connor J, Fitton JH, et al. A combined phase I and II open label study on the effects of a seaweed extract nutrient complex on osteoarthritis. Biologics. 2010;4:33–44. doi: 10.2147/btt.s8354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeguchi M, Yamamoto M, Arai Y, et al. Fucoidan reduces the toxicities of chemotherapy for patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2011;2(2):319–322. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitton J. Therapies from fucoidan; multifunctional marine polymers. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1731–1760. doi: 10.3390/md9101731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson KD, Dragar C. Antiviral activity of Undaria pinnatifida against herpes simplex virus. Phytother Res. 2004;18(7):551–555. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi T. Studies on evaluation of natural products for antiviral effects and their applications. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128(1):61–79. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.128.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negishi H, Mori M, Mori H, Yamori Y. Supplementation of elderly Japanese men and women with fucoidan from seaweed increases immune responses to seasonal influenza vaccination. J Nutr. 2013;143(11):1794–1798. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.179036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzo-Silberman S, Louedec L, Meilhac O, Letourneur D, Michel JB, Elmadbouh I. Therapeutic potential of fucoidan in myocardial ischemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58(6):626–632. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182308c64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim EJ, Park SY, Lee JY, Park JH. Fucoidan present in brown algae induces apoptosis of human colon cancer cells. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamasaki-Miyamoto Y, Yamasaki M, Tachibana H, Yamada K. Fucoidan induces apoptosis through activation of caspase-8 on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(18):8677–8682. doi: 10.1021/jf9010406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azuma K, Ishihara T, Nakamoto H, et al. Effects of oral administration of fucoidan extracted from Cladosiphon okamuranus on tumor growth and survival time in a tumor-bearing mouse model. Mar Drugs. 2012;10(10):2337–2348. doi: 10.3390/md10102337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185–199. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):795–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Robertson J, Jones AC, Dieppe PA, Doherty M. The placebo effect and its determinants in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(12):1716–1723. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang T, Jonsdottir R, Liu H, et al. Antioxidant capacities of phlorotannins extracted from the brown algae Fucus vesiculosus. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(23):5874–5883. doi: 10.1021/jf3003653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulejova H, Baresova V, Klezl Z, Polanská M, Adam M, Senolt L. Increased level of cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in osteoarthritic subchondral bone. Cytokine. 2007;38(3):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siebuhr AS, Petersen KK, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Identification and characterisation of osteoarthritis patients with inflammation derived tissue turnover. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers SP, O’Connor J, Fitton JH, et al. A combined phase I and II open-label study on the immunomodulatory effects of seaweed extract nutrient complex. Biologics. 2011;5:45–60. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irhimeh MR, Fitton JH, Lowenthal RM, Kongtawelert P. A quantitative method to detect fucoidan in human plasma using a novel antibody. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2005;27(10):705. doi: 10.1358/mf.2005.27.10.948919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokita Y, Nakajima K, Mochida H, Iha M, Nagamine T. Development of a fucoidan-specific antibody and measurement of fucoidan in serum and urine by sandwich ELISA. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(2):350–357. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irhimeh MR, Fitton JH, Lowenthal RM. Fucoidan ingestion increases the expression of CXCR4 on human CD34+ cells. Exp Hematol. 2007;35(6):989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frenette PS, Weiss L. Sulfated glycans induce rapid hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization: evidence for selectin-dependent and independent mechanisms. Blood. 2000;96(7):2460–2468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osaki T, Kitahara K, Okamoto Y, et al. Effect of fucoidan extracted from mozuku on experimental cartilaginous tissue injury. Mar Drugs. 2012;10(11):2560–2570. doi: 10.3390/md10112560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren R, Azuma Y, Ojima T, et al. Modulation of platelet aggregation-related eicosanoid production by dietary F-fucoidan from brown alga Laminaria japonica in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(5):880–890. doi: 10.1017/S000711451200606X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findlay DM. Vascular pathology and osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2007;46(12):1763–1768. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh P, Cheras PA. Vascular mechanisms in osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15(5):693–709. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]