Abstract

Objective

Little is known about perceptions surrounding academic interventions for ADHD that determine intervention feasibility.

Method

As part of a longitudinal mixed-methods research project, representative school district samples of 148 adolescents (54.8%), 161 parents (59.4%), 122 teachers (50.0%), 46 health care providers (53.5%), and 92 school health professionals (65.7%) completed a cross-sectional survey. They also answered open-ended questions addressing undesirable intervention effects, which were analyzed using grounded theory methods.

Results

Adolescents expressed significantly lower receptivity toward academic interventions than adult respondents. Stigma emerged as a significant threat to ADHD intervention feasibility, as did perceptions that individualized interventions foster inequality.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that adolescents’ viewpoints must be included in intervention development to enhance feasibility and avoid interventions acceptable to adults, but resisted by adolescents.

Keywords: academic, adolescent ADHD, parent–teacher agreement, stigma, treatment acceptability

Introduction

ADHD is a serious childhood neurodevelopmental disorder that affects an estimated 5% of youth worldwide (Polanczyk, de Lima, Horta, Biederman, & Rohde, 2007), with recent household surveys indicating that 8% of U.S. children are affected. The academic and social implications of ADHD symptomology are far reaching. Socially, these youth may alienate peers and teachers (Chew, Jensen, & Rosen, 2009). Moreover, youth with ADHD commonly experience more academic and academic-related problems than their peers without ADHD, including (a) worse grades, (b) lower standardized tests scores, (c) greater likelihood of need of special education services, (d) higher absenteeism rate, (e) greater likelihood of retainment in grade, (f) higher risk of dropping out of school, and (g) less likelihood of pursuit of a postsecondary education (Bussing, Mason, Bell, Porter, & Garvan, 2010; DuPaul, Weyandt, & Janusis, 2011; Molina et al., 2009).

In schools, youth with ADHD are typically provided educational support for ADHD under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; 2004) or they may receive services under a Section 504 plan (deBettencourt, 2002; Schnoes, Reid, Wagner, & Marder, 2006). Within IDEA regulations (2006), ADHD is included under the category of “Other Health Impairments” (OHI) and is characterized by

having limited strength, vitality, or alertness, including a heightened alertness to environmental stimuli, that results in limited alertness with respect to the educational environment, that is due to chronic or acute health problems such as … attention deficit disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. (Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act Regulations, 2006)

However, there is a dominant paradigm in education that also promotes proactive supports for youth who have not been classified with a disability. Specifically, Response to Intervention (RTI) is an intervention model that typically consists of three tiers of instructional support, wherein intensity and individualization of intervention increase at each tier (D. P. Bryant, Bryant, Gersten, Scammacca, & Chavez, 2008). In light of the emphasis on RTI, it is important to consider academic interventions for both youth with OHI (ADHD) and those at risk of being classified as OHI.

In addition to recognizing the importance of academic intervention efficacy, there is also increasing recognition that usability and feasibility of interventions is critical to translate research to practice within the classroom. In fact, within the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES), requirements for research and development projects specifically include the evaluation of feasibility for all interventions (IES, 2012). IES identifies that, “Feasibility of the intervention shows that the end user can use the intervention within the requirements and constraints of an authentic education delivery setting” (p. 44). In practical terms, feasibility concerns willingness of key stakeholders (e.g., adolescents, parents, health professionals, and teachers) to use, participate in, or support academic interventions, while considering their perceived effectiveness and undesirable consequences, such as anticipated stigma (Bell et al., 2011; Hinshaw, 2005; Martin, Pescosolido, Olafsdottir, & McLeod, 2007). Not only must these factors be considered with regard to feasibility but also an evaluation of an academic intervention must also consider variations in the views of the noted stakeholders (see Wiener et al., 2012). For example, youth with ADHD may have different views of the acceptability of certain academic interventions compared with important adults in their lives (McNeal, Roberts, & Barone, 2000). Furthermore, youth with ADHD have been found to exhibit significant positive illusory bias about their own symptoms and functioning, placing them at odds with adult perceptions (Owens, Goldfine, Evangelista, Hoza, & Kaiser, 2007) and vulnerable to perceptions of differential treatment and stigmatization due to ADHD symptoms (Wiener et al., 2012). Clearly, to translate research findings to practice, it is essential to understand the extent to which students’ views differ from those of important adults.

The current research was embedded in a longitudinal mixed-methods study of help seeking and barriers to ADHD interventions. Interventions from three domains considered relevant for children with ADHD (academic, health sector, and self-care) were chosen for survey inclusion through a sequential process including: (a) qualitative methods aimed at identifying community academic practices through a sequence of longitudinal experience sampling and focus groups eliciting perspectives of adolescents, parents, and teachers on helpful interventions (citations blinded for review); (b) review of health sector ADHD practice guidelines and practice parameters (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001; Pliszka, 2007); (c) review of educational interventions and accommodations for ADHD (DuPaul, 2007; Schnoes et al., 2006) and of research supported academic interventions; and (d) survey pilot testing to confirm final item selection, adjust wording and improve item clarity. Through this process, we selected 18 interventions. Eighteen interventions were chosen for two reasons: (a) to keep the survey length manageable and (b) to expand upon solely research-based approaches and to include interventions grounded in current practice and identified as helpful during focus groups (Bussing et al., 2012). The current report focuses on 7 of the 18 interventions that relate specifically to academics and respondents’ views on intervention feasibility. The remaining interventions related to the health sector and self-care are reported elsewhere (Bussing et al., 2012).

Next, we will provide a brief review of evidence associated with each of the seven academic interventions included in the survey and identify whether the intervention was selected as helpful community practice (CP) based on responses to focus groups or was chosen because it represented a research supported practice (RSP). The exact wording of the intervention used for the survey is shown in the methods section. In the first academic intervention, teachers may offer students constructive ways to keep engaged (CP). Limited information exists that indicates scheduled breaks and regular exercise have positive effects on student on-task behavior, reduces fidgeting, and/or lowers the need for psychostimulant medication (Azrin, Ehle, & Vinas, 2006). Second, teachers may allow students more movement during academic tasks (CP). Although research is limited, incorporating physical activity into lessons is a potentially helpful academic intervention for youth with ADHD (Cooley, 2007) and use of stress balls shows promise for reducing the frequency of distraction incidents during teacher led instruction and student independent practice of skills (Stalvey & Brasell, 2006). Third, teachers may reduce sources of distraction for students with ADHD by seating them (a) away from noises, (b) closer to the teacher, or (c) away from other talkative students (CP). In a review of literature, Trout, Lineman, Reid, and Epstein (2007) reported that lower noise levels may be linked to increased accuracy on assignments. Fourth, teachers may provide reminder systems to help with organization (e.g., planners, posted notes, posted rules; RSP). Organizational systems can be an effective academic support for youth with and at risk of ADHD (DuPaul et al., 2011; Langberg, Epstein, Urbanowicz, Simon, & Graham, 2008). Fifth, teachers may restructure difficult tasks (CP). For example, large assignments may be broken into a series of smaller assignments with separate deadlines for each component of the project. Teachers may also shorten assignments. Although widely used as academic interventions, there is a dearth of research on the efficacy of task or instructional modifications for youth with and at risk of ADHD and the research that has been completed has troubling limitations (Raggi & Chronis, 2006). Sixth, schools may assign students with and at risk of ADHD with a “point of contact” teacher (CP). The purpose of this arrangement is to provide an adult who is able to coordinate communication between home and school and inform other teachers of the student’s needs or problems. Although focus group participants indicated that they experienced, used, or found having a “point of contact” teacher appealing, no study has assessed the benefits of this approach with regard to youth with or at risk of ADHD. Finally, teachers may offer assessment accommodations to students (CP). “Assessment accommodations alter assessment materials and/or procedures in order to remove the influence of student disability and allow for an accurate assessment of student knowledge” (Gagnon, Maccini, & Haydon, 2011). Extended time on assessments is one of the most common assessment accommodations provided to youth (Bolt & Thurlow, 2004), despite limited evidence that increased time provides any “differential boost” or support for youth with or at risk of ADHD that is above and beyond the effect on students without disabilities (Lewandowski, Lovett, & Rogers, 2008).

Purpose

The current research seeks to address gaps in our knowledge base on intervention feasibility by simultaneously eliciting ADHD intervention perceptions from four stakeholders: adolescents, parents, health care professionals, and teachers. Specifically, the study assessed participants’ willingness to use school-based ADHD interventions and corresponding views of acceptability, effectiveness, and potential undesirable effects associated with interventions. The study sought to answer the following two quantitative and one qualitative research questions:

Research Questions 1: What are the differences in willingness to use or recommendations to use school-based interventions for ADHD across adolescents, parents, health professionals, and teachers? Based on existing research on willingness and positive illusory bias we hypothesized that adolescents would express lower willingness than any adult respondent group for any ADHD interventions.

Research Questions 2: What perceptual and experiential factors predict willingness to use ADHD interventions? We hypothesized that for all respondent groups intervention willingness would increase along with higher perceptions of acceptability and effectiveness but decrease along expectations of unintended effects and stigma. We further hypothesized that personal experience with special education intervention would affect willingness, but did not have a directional hypothesis.

Research Questions 3: What concerns about unwanted effects of school-based ADHD interventions do teachers, adolescents, parents, and health professionals express?

Method

Instrumentation

Items for the intervention perception survey were developed through the four-step process described above, including qualitative research, treatment guidelines review, research literature review, and pilot testing. To anchor survey responses, we developed case vignettes describing a male and a female child with sufficient Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychological Association, 1994) symptoms to qualify for an ADHD diagnosis, and respondents answered questions regarding the person in the vignette, referred to with the fictitious names of “Jennifer” or “Joseph.” Vignette gender was randomly assigned for teacher and health professionals, and was matched to the gender of the study adolescent for youth and their parent. Case vignettes have been successfully employed in other research studies eliciting perceptions and opinions regarding ADHD and interventions (Pescosolido et al., 2008). After reading the vignette, respondents were asked to complete survey questions about possible interventions for the child with ADHD. Respondents were instructed to select the answers that best fit their personal opinions and feelings, and that there were no correct or incorrect answers.

The seven academic interventions included in this study were presented to respondents with the following wording: (a) Teacher offers constructive ways for students with ADHD to be busy (e.g., running errands for teacher after completing assignments; giving regular exercise breaks); (b) teacher allows students with ADHD more movement in class (e.g., permitting students to be out of their seat and work standing up, allowing use of objects like stress balls or straws to fidget in ways that do not annoy others); (c) teacher reduces sources of distraction for students with ADHD by seating them away from noises, closer to teacher, or away from other chatty students; (d) teacher uses reminder system for students with ADHD to help with organization (e.g., planners, posted notes, posted rules); (e) teacher helps students with ADHD by restructuring difficult tasks, like breaking large assignments into small pieces, setting deadlines for individual tasks within a large project, or shortening assignments; (f) school assigns “point of contact” teacher who coordinates communications between home and school, informs other teachers of student’s needs or problems, keeps regular contact, and gives out information for the student with ADHD; and (g) school provides accommodations to facilitate good test performance for students with ADHD, like extended time on testing or other test taking accommodations.

After reading the vignette, respondents rated each of the seven interventions on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 3 = moderately, 5 = very) for acceptability, perceived effectiveness/helpfulness, potential to be embarrassing (intended to represent a proxy for intervention stigma), likelihood to cause undesirable effects, and their self-rated level of knowledge about the intervention. The wording was fit to each domain of inquiry (e.g., 1 = not acceptable at all, 3 = moderately acceptably, 5 = very acceptable). Respondents then rated their willingness to use a given intervention or recommend its use (1 = not willing at all, 3 = moderately willing, 5 = very willing). In addition, embarrassment ratings were followed by the open-ended question “What other undesirable effects are you concerned about?” and respondents could write about any other effects they attributed to the intervention. Respondents also indicated (i.e., yes, no) whether they had personally experienced, used, or recommended the intervention.

Information about respondent gender, race, age, and socioeconomic status (SES) was also obtained through survey questions. SES scores were calculated using the Hollingshead 4-factor Index (Hollingshead, 1975).

Participant Selection

The parents and adolescent participants for this survey study (conducted 2007–2008) were part of a longitudinal mixed-methods study of ADHD detection and service use in the United States (conducted 1998–2009) and included cohort members of our ADHD high-risk group and of our low-risk peer group (Bussing et al., 2010) originally identified in 1998. The study setting was a school district in North Florida containing an urban center and several smaller communities with rural characteristics. Parent and student participants were originally derived from stratified random sampling of public school records in 1998. Due to the common overrepresentation of males with ADHD (Cuffe, Moore, & McKeown, 2005), girls were oversampled by a factor of 2 to ensure sufficient representation. Parents of 1,615 elementary school students completed telephone screening interviews and teachers made behavior ratings of 1,205 of these students. Based on screening results, children were assigned to the ADHD high-risk group if they were previously clinically diagnosed with ADHD, specifically suspected of having ADHD, but not yet assessed, or obtained elevated parent and teacher ADHD behavior ratings on a validated screening measure (Bussing et al., 2010). Study participants without prior ADHD diagnosis or concerns whose behavior ratings were in the normal range were assigned to low-risk status after initial screening. Between 1998 and 2008, the high-risk children participated in several waves of data collection and for the final outcomes assessment, were matched by gender, race, poverty status, and age with the comparison group of peers classified as low risk in 1998 (Bussing et al., 2010). For this survey, we invited high and low-risk youth of the original sample to participate. Teachers were randomly selected from the local school district staff database and were not specifically associated with the participating adolescents. Health professionals consisted of two groups of participants. The first group consisted of school health professionals, including school nurses, psychologists, and guidance counselors, who were randomly selected from the local school district staff database. The second group of health professionals represented participating high-risk adolescents’ current or past ADHD treatment providers who had been identified during our service assessment interviews and included pediatricians, social workers, psychologists, and child psychiatrists.

Data Collection

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida approved this study. Parental consent and child assent were obtained for all surveys completed by adolescents. Written informed consent was waived for all adult participants, instead, completion of the survey constituted consent. Participants received the survey in the mail, completed it, and then mailed it back. Parent and adolescent participants also had the option of completing the survey questionnaire during a study visit conducted at a location of their choice (e.g., home, research office, and community library). To increase participation rates, participants received reminder phone calls if the survey had not been mailed back after 3 weeks from the date originally mailed. If the participant indicated that they had not received the survey or had lost/misplaced it, the address was verified and another copy was mailed out. This procedure was repeated 2 weeks after the mailing of the second copy. Respondents received a US$15 gift card incentive upon survey completion.

Respondents and Nonrespondents

The survey was completed by 569 participants and included 161 parents, 148 adolescents, 138 health professionals composed of 46 ADHD treatment providers and school health professionals, and 122 school district teachers. Numbers of responders, participant’s refusing, failures to reply, and total invited for each participant group were as follows: parents (161/30/80/271), adolescents (148/36/86/270), ADHD treatment providers (46/11/29/86), school professionals (92/14/34/140), and teachers (122/47/74/243), respectively. Thus, the response rates ranged from 50% to 66%, refusal rates from 10% to 19%, and the remaining nonparticipants were unreachable or failed to return surveys without expressing explicit refusal.

Sociodemographic information and ADHD risk status was available prior to participation for adolescents and their parents, but not for health professionals. There were statistically significant differences in the race of respondents, such that African American adolescents were less likely than their white counterparts to complete the survey (46% vs. 59%, p = .032). There were no statistically significant differences in the free or reduced lunch status of respondents and nonrespondents. Adolescent and parent participation did not differ statistically by ADHD risk status. For teachers, the only information available prior to participation was teacher assignment (elementary school, middle/high school, varying exceptionalities). No statistically significant differences existed between teacher respondents and nonrespondents.

Respondent Characteristics and Personal Experience With ADHD Interventions

Adolescent age ranged from 14 years to 19 years (M = 16.5 years; SD = 1.3 years) and 59% were females; adult participants consisted mostly of females (96% of parents, 73% of teachers and 82% of health professionals. Most parents were in the 41- to 50-year-age range, whereas teacher and health professional ages were more varied. Consistent with participant differences in educational backgrounds and professional status, Hollingshead scores were higher for health professionals (57, SD = 2.2) and teachers (60, SD = 4.2) than for adolescent (39, SD = 14.2) and parent participants (41, SD = 14.6). Average length of professional experience was similar for teachers (15.0 years, SD = 11.0) and health professionals (15.6 years, SD = 10.7). Of the 148 adolescents, 55 (37%) had never received special education services, 50 (34%) had received services for emotional disturbance (ED) or specific learning disabilities (SLD), and 43 (29%) qualified for the gifted classification. The corresponding numbers (and percentages) for parents, reflecting their child’s disability status, were 59 (37%), 54 (33%), and 48 (30%). Respondents reported varying degrees of personal experience with the interventions included in the survey. Less than half of adolescents and parents reported personal experiences with activity-focused interventions (27% and 39%, respectively) or point of contact teachers (16% and 39%, respectively), whereas 60% of adolescents and 75% of parents reported experience with attention-focused interventions. Almost all teachers and health professionals reported personal experience with activity-focused (92% and 84%, respectively) and attention-focused interventions (100% and 96%, respectively), and approximately half of them had experience with point of contact teacher arrangements (48% and 55%, respectively).

Data Analysis

Our original dependent variables consisted of the seven willingness ratings previously noted. To be consistent with extant literature on school-based interventions, we also constructed composite willingness variables for activity-focused interventions (i.e., combining ratings of offering constructive busy tasks and allowing more movement), as well as for attention-focused interventions (i.e., combining ratings of reduced distraction, organizational aids, task restructuring, and test accommodations). Internal consistency of the composite variables was high, with Cronbach’s coefficient alpha estimates of .71 and .77, respectively. Assignment of point of contact teacher was maintained as a separate variable.

To address Research Question 1, we conducted a Kruskal–Wallis analysis for each of the seven original dependent variables (i.e., intervention willingness) as a function of our main independent predictor variable (i.e., respondent type), followed by Bonferroni corrected Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Research Question 2 was addressed by conducting multiple regression analyses for the two composite dependent variables (i.e., activity-focused, attention-focused) and the point-of-contact teacher variable. The model’s independent variables were potentially mutable perceptual variables (i.e., feeling knowledgeable, intervention acceptability, effectiveness, side effects, potential embarrassment), adjusting for respondent characteristics, including respondent type and for other potential confounding respondent sociodemographic predictors (i.e., age, race, SES, gender) simultaneously introduced into the regression equations. A set of subanalyses tested whether adolescents’ (and their parents’) personal special education service experience predicted intervention willingness. We conducted Kruskal–Wallis analyses for each of the seven willingness variables by an independent three-level variable that distinguished students (or parents of these students, respectively) who had not received special education services experience from those who had. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, 2008) and level of significance was set at ptwo-tailed = .05.

To address Research Question 3, we applied grounded theory methods to analyze open-ended survey responses to the question “what other undesirable effects are you concerned about?” Even though grounded theory methods are more typically used for data yielding more extensive responses (e.g., from semistructured interviews), our written data set provided numerous elaborated written responses that supported constant comparison, productive detailed analysis, and theory development. Our multidisciplinary qualitative data analysis team, consisting of a qualitative research methodologist, a child and adolescent psychiatrist ADHD expert and services researcher, a graduate student in social work and a senior undergraduate psychology student. All team members were trained by the qualitative methodologist to code, compare data and emerging codes, and to synthesize data. The research team created a shared codebook and engaged in ongoing team discussions about the data content. The codebook and the emerging list of open codes were continuously discussed and revised together. Examples of open codes included feeling different, disruptive to academics, inconsistency in use, and combination treatment needed. We followed Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) subsequential steps for axial coding and selective coding. During axial coding, we sought to identify explicit connections between categories and subcategories. Examples of axial codes included stigma, negative reactions from others, psychological side effects, burden, and beliefs about treatment. We also developed selective codes through constant comparison with the intention of reducing and selecting codes to develop theory (A. Bryant & Charmaz, 2007). Theoretical codes were used to achieve an integrated theoretical model describing participants’ perceived implementation barriers (i.e., inequality, perceived ineffectiveness, and confidentiality concerns) and perceived unintended effects (i.e., stigma, disruptions, and future dependence).

Results

Quantitative Findings

Respondent willingness to use interventions

As hypothesized, adolescents expressed significantly lower willingness than adult respondents for all seven ADHD interventions. Six of the seven Kruskal–Wallis analyses were significant with p values less than .0001, whereas the analysis for “Keep Busy” was significant at p value of .0035. Pairwise comparison testing with Bonferroni correction indicates that adult respondent groups did not differ in their intervention willingness (“keep busy” = 3.8/3.7/3.5 and “allow movement” = 3.3/3.5/3.6, for parent [P]/health professional [HP]/teacher [T], respectively), whereas adolescents (A) showed lower willingness (3.3) than parents to “keep busy” (p value = .0008) as well as lower willingness (2.6) than all three adult group to “allow movement” (all with p < .0001). For attention-focused interventions, in pairwise comparisons, adult respondents generally did not differ in their willingness (“reduce distraction” = 3.5/3.8/41/2.6; “reminders” 4.0/4.1/4, 1/3.3; “restructure tasks” 4.0/4.1/3.9/3.4; “test accommodations” 4.0/4.1/4.3/3.2, for P/HP/T/A, respectively), with the exception being higher teacher than parent willingness to use “reduce distraction” strategies (p value less than .0001). In addition, adolescents generally expressed significantly lower willingness than all three adult groups to use attention-focused interventions (all with p values less than .0001), with the exception of a lack of difference from teacher willingness to “restructure tasks.” Regarding willingness to use point-of-contact teacher (3.9/3.7/3.4/2.4, for P/HP/T/A, respectively), among the three adult groups, teachers expressed lower willingness to employ the strategy than parents (p value = .0002). Adolescents expressed significantly lower willingness than all three adult groups (all with p values less than .0001) to use a point-of-contact teacher.

Predictors of intervention willingness

Our multiple regression prediction model of activity-focused intervention willingness was statistically significant, F(13/537) = 57.13, p < .0001, and explained a considerable amount of response variance (R2 = .58). Regression coefficients (βs) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Willingness to Use Academic Interventions.

| Activity-focused

|

Attention-focused

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t value | p | β | SE | t value | p | |

| Intervention perceptions | ||||||||

| Knowledgeable | .23 | 0.04 | 6.36 | <.0001 | .34 | 0.03 | 10.90 | <.0001 |

| Acceptable | .52 | 0.05 | 9.56 | <.0001 | .49 | 0.04 | 11.05 | <.0001 |

| Effective | .18 | 0.06 | 3.30 | .001 | .07 | 0.04 | 1.82 | .0688 |

| Embarrassing | −.01 | 0.05 | −0. 95 | .3448 | −.13 | 0.05 | −2.78 | <.0056 |

| Likely side effects | −.17 | 0.05 | −3.71 | .0002 | −.07 | 0.05 | −1.42 | .1555 |

| Respondent characteristics | ||||||||

| Parenta | .14 | 0.10 | 1.49 | .1360 | .42 | 0.08 | 5.42 | <.0001 |

| Teachera | −.07 | 0.12 | −0.60 | .5514 | .34 | 0.09 | 3.76 | .0002 |

| Health professionala | −.02 | 0.12 | −0.18 | .8564 | .27 | 0.09 | 2.98 | .0030 |

| Personal experience | −.13 | 0.09 | −1.45 | .148 | .02 | 0.08 | 0.21 | .333 |

| AA/Other vs. Caucasian | −.08 | 0.08 | −0.94 | .3481 | −.06 | 0.07 | −0.92 | .3572 |

| Male vs. female | −.05 | 0.09 | −0.65 | .5135 | .09 | 0.07 | 1.31 | .1901 |

| SES middle classb | .08 | 0.14 | 0.58 | .5609 | −.07 | 0.11 | −0.69 | .4918 |

| SES upper classb | .10 | 0.12 | 0.87 | .3857 | −.05 | 0.09 | −0.52 | .6047 |

Note. AA = African American; SES = socioeconomic status.

Comparison group is adolescents.

Comparison group is SES lower class (Hollingshead IV/V).

As shown in more detail in Table 1, of the hypothesized perceptual predictors only embarrassment was not significantly associated with willingness to use activity-focused interventions. Such willingness was increased by feeling knowledgeable, and by considering activity-focused interventions acceptable and effective (β estimates of .23, .52 and .18, respectively), but was reduced by anticipation of negative side effects (β estimate of −.17). Respondent type was not significantly associated with willingness to use activity-focused interventions after controlling for perceptual and sociodemographic characteristics. Respondent race, gender, and SES were not independently associated with willingness to use activity-focused interventions.

The multiple regression prediction model of willingness to use attention-focused interventions also was statistically significant, F(13/540) = 68.29, p < .0001, explaining considerable amounts of response variance (R2 = .62). Regression coefficients (βs) are presented in Table 1. As for activity-focused interventions, willingness was increased by feeling knowledgeable (β estimate of .34), and by considering attention-focused interventions acceptable (β estimate of .49). However, unlike in the previous model, embarrassment was significantly associated with willingness (β estimate of −.13), whereas perceptions of effectiveness and of likely side effects were not. Respondent type was significantly associated with willingness to use attention-focused interventions after controlling for perceptual variables and sociodemographic characteristics, such that parents, teachers and health professionals expressed significantly higher willingness than adolescents (β estimates of .42, .34, and .27, respectively). Results of multiple comparison testing, using the Tukey–Kramer adjustment, failed to show differences in parents’ (M = 3.9), teachers’ (M = 3.8), and health professionals’ activity-focused intervention willingness (M = 3.8).

Similar findings apply to willingness to use a point-of-contact teacher, where the prediction model was statistically significant, F(13/523) = 52.33, p < .0001, and explained considerable variance (R2 = .57). Betas are presented in Table 2. Of the hypothesized predictors, only embarrassment was not significantly associated with willingness to use point-of-contact teachers. Furthermore, respondent type was significantly associated with willingness to use this intervention after controlling for perceptual variables and sociodemographic characteristics, such that parents, teachers and health professionals expressed significantly higher willingness than adolescents (β estimates of .82, .41, and .47, respectively) to involve a point-of-contact teacher. Results of multiple comparison testing, using the Tukey–Kramer adjustment, further showed that willingness to involve point-of-contact teachers was greater in parents (M = 3.7) than either teachers (M = 3.3; p = .0060) or health professionals (M = 3.3; p = .0286), who in turn did not differ from each other (p = .943).

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Willingness to Use Point of Contact Teacher.

| β | SE | t value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention perceptions | ||||

| Knowledgeable | .27 | 0.04 | 6.87 | <.0001 |

| Acceptable | .43 | 0.04 | 6.87 | <.0001 |

| Effective | .16 | 0.04 | 3.63 | .0003 |

| Embarrassing | −.05 | 0.04 | −1.10 | .2699 |

| Likely side effects | −.15 | 0.04 | −3.77 | .0002 |

| Respondent characteristics | ||||

| Parenta | .82 | 0.12 | 6.95 | <.0001 |

| Teachera | .41 | 0.13 | 3.18 | .0016 |

| Health professionala | .47 | 0.13 | 3.66 | .0003 |

| Personal experience | −.07 | 0.11 | −0.64 | .5252 |

| AA/Other vs. Caucasian | −.14 | 0.10 | −1.47 | .1424 |

| Male vs. female | .10 | 0.10 | 1.07 | .2867 |

| SES middle classb | −.06 | 0.16 | −0.37 | .7113 |

| SES upper classb | .13 | 0.14 | 0.95 | .3401 |

Note. AA = African American; SES = socioeconomic status.

Comparison group is adolescents.

Comparison group is SES lower class (Hollingshead IV/V).

Special education service and intervention willingness

Examination of whether treatment willingness varied by special education service experience revealed no differences for adolescents or parents in any of the seven interventions.

Qualitative Findings

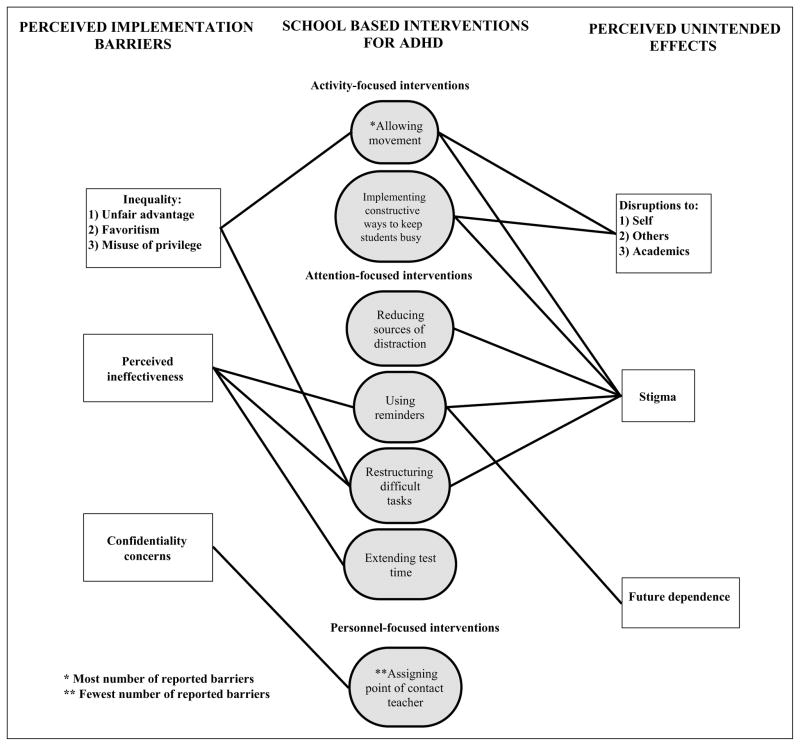

Parents, teachers, and health professionals had similar written response rates, whereas adolescents provided fewer written responses. Participants’ response lengths varied from one word to lengthy paragraphs. Generally, all respondents mentioned the identified thematic clusters and categories and our model applies to all participants groups (see Figure 1). Some participants referred to multiple and overlapping interventions whereas others focused on one or two most important or central interventions. School-based ADHD interventions elicited concerns that served as barriers to implementation, including perceptions of inequality bestowed through the interventions, perceptions of intervention ineffectiveness, and limited confidentiality. Furthermore, respondents identified concerns about unintended negative effects of ADHD interventions in the form of stigma arising from being an intervention recipient, disruptions to self, others, and the academic environment due to interventions and the fostering of intervention dependence. Participants reported that activity-focused interventions were associated with the most implementation barriers whereas personnel-focused interventions were seen as less affected by different barriers and negative expectations.

Figure 1.

Undesirable effects of school-based interventions for ADHD.

We also found that various barriers and unintended effects of interventions shape teachers, parents, and teenagers’ willingness to suggest, engage in, sustain, and carry out different interventions. For example, study participants reported that activity-focused interventions were mostly seen as disruptive. As a result of this perception, teachers and parents who worried about classroom disruptions and disorderly conduct might not suggest or allow students to move around the classroom. In addition, perceptions of stigma were linked to the majority of discussed interventions. When teachers and parents considered scenarios where activity and attention-focused interventions would be used, their concerns about stigma also impacted the ways in which they conceptualized ineffectiveness and inequality of activity and attention-focused interventions. Perceived barriers and unintended effects together shaped the discourses around proposed interventions. Personnel-focused interventions were also seen as important but interestingly our participants were not concerned about the effectiveness, inequality, or stigma associated with a point of a contact teacher. It is possible that a point of contact teacher was considered less intrusive because assigning a contact teacher was only remotely related to the adolescents themselves, and teachers were seen as an additional supportive resource. In comparison when considering implementation of activity and attention-focused interventions children, their routines, behaviors, and social environment must go through more visible transformation and adolescents themselves are more deeply involved and impacted.

Inequality

More specifically, participants were sensitive to the issues of equality and fairness of the proposed interventions. It seemed that many parents, teachers, teenagers, and health care providers viewed education as a social good that should be distributed equally. When participants were asked about potential concerns regarding school-based interventions they reported that activity and attention-focused interventions could promote unfair advantages and favoritism. They also reported that these interventions could lead students to misuse privileges and pedagogical and instructional exceptions. Teachers worried that other students and parents would complain about special privileges and parents were concerned about “special treatment” leading to increased teasing and isolation by peers. Teachers, parents, and health care providers also proposed that inequality or differentiated instructions and individually tailored rules could stimulate students to manipulate problems and given privileges to their advantage.

Furthermore, some parents recommended that restructuring difficult tasks “should be for any student who is not prone to be good at a specific subject” and “these rules should be applied to the entire class.” Teachers are also worried about inequality: “I think they all need to be treated the same way. Everyone in a class needs to be required to do the same assignments.” Our participants emphasized that education and school-based activities would need to provide equal opportunities for all students and education is a way to decrease achievement gaps and existing injustices. Furthermore, education was expected to be fair and thus favoritism and misuse of privileges were viewed to hinder this goal. All students should have access to accommodations, if needed, according to many parents. Some parents also proposed that it might be hard to find teachers who are willing and able to provide extra help and accommodations. This access to helpful teachers or lack of them could further promote inequality. Some teachers, in turn, expressed that they cannot possibly accommodate all students needing special attention or modifications.

Ineffectiveness

Participants viewed most attention-focused interventions as ineffective in isolation and not to be used without other interventions such as medication, therapy, or behavioral modifications. Participants noted that school-based interventions or that these interventions can be only carried out in particular settings. For example, a teacher noted that restructuring a task is not realistic; “the real world is not going to do this. It puts the burden on the teacher not the student.” Health care professionals proposed that extending test time is a good single strategy but that it would need to be combined with other strategies.

Privacy

It was also noted that assigning a particular teacher to be a student’s and parents’ main contact could improve home–school communication and distribution of different responsibilities among stakeholders. However, some respondents expressed concerns that this intervention could break confidentiality and further stigmatize the student when information about his or her disorder was shared with additional individuals. In addition, the implementation of a “middle-man” could facilitate discontinued and fragmented communication. Teachers worried about “crossing lines for FERPA laws and student privacy.” Some parents worried that confidential information could be used against the student and that if contact teachers shared confidential information, they might not follow all safety procedures. Contact teachers might also have “a big mouth” which might lead to leaks in privacy information or potential “communication breakdowns.”

Disruption

Many parents, teachers, teens, and health care providers recognized the need to allow students with ADHD to move around in the classroom, enable students to find constructive ways to channel their extra energy, and to accommodate their desire to manipulate objects. However, these activity-focused interventions were also seen to create potential “disruptions of academic progress both to the student receiving the intervention as well as other students in the classroom.” Movement and constructive ways to stay busy might also decrease productivity and “moving around may cause a child to miss the key point of a lecture.” Similarly, teenagers worried how “constant going and leaving can be even more distracting.” With regard to activity-focused interventions, some teachers noted that they would rather use non-disruptive strategies that can be implemented without having the student leave the desk. Allowing movement could create “too many opportunities for getting into trouble.”

Stigma

We found that all school-based interventions were seen to increase stigma and feelings of “being different” to some degree, but activity and attention-focused interventions were seen as most stigmatizing. Many parents worried that activity and attention-focused accommodations resulted in teenagers standing out. In addition, an intervention where teachers were to implement constructive ways to keep students busy was perceived to lead to favoritism, other students becoming jealous, or the singled out students being seen as “teachers’ pets” by other students. Teenagers worried that reducing sources of distraction would be too embarrassing, making students stand out and feel uncomfortable. Even though concerns were less numerous, extending test time and assigning a point of contact teacher were also considered stigmatizing despite these interventions being less visible. “Extended time can isolate students into small special groups, which do not necessarily boost their confidence. Rather they feel like something is ‘wrong’ with them.”

Dependence

Finally, the use of reminders was also considered potentially helpful but ineffective on its own, and thought to create stigma and dependence on similar strategies in the future. Students might become dependent on planners, reminders, and they may lose reminders and planning devices. Parents and teachers worried about students being too dependent on assistance and not being able to develop self-monitoring techniques or reminder systems on their own. Furthermore, some participants noted that students may “rely totally on the teacher to write down assignments and notes,” and use of reminders does not promote self-monitoring.

Discussion

Findings of the current study indicate that adolescents express significantly lower receptivity toward academic interventions for ADHD than adult respondents, including teachers, parents and health care professionals. Qualitative analysis revealed several misperceptions surrounding ADHD interventions that warrant further exploration and confirmation in future studies. Below, we discuss each of the findings, as well as implications for research and practice.

Willingness Differences by Respondent Type

As hypothesized, study findings indicate that academic interventions are perceived quite differently by adolescents than by relevant adults in their lives, including parents, teachers, and health professionals who provide ADHD treatments through the health sector. Not only did adolescents express significantly less ADHD intervention willingness than adults but also expressed low willingness for the most part. In contrast, adults expressed fairly high willingness to use interventions, with no or minor differences among adult respondent groups. Some studies have examined the acceptability of mental health treatments among parents, teachers, and children (see, for example, Curtis, Pisecco, Hamilton, & Moore, 2006; Johnston, Hommersen, & Seipp, 2008; Krain, Kendall, & Power, 2005). However, limited research exists on academic ADHD intervention willingness to use as a comparison for our findings. High adult and low adolescent intervention acceptability was reported by Molina, Smith, and Pelham (2005) in the process of developing school-wide behavior management system intended to positively affect students with ADHD.

Perceptual and Experiential Predictors of Intervention Willingness

As hypothesized, greater knowledge about an intervention and perceptions that the intervention is effective and has limited adverse effects is related to increased respondents’ willingness to use interventions. In our qualitative inquiry, all four respondent types depicted stigma as an undesirable, potent, unintended effect of most academic intervention. These findings are consistent with recent research that identifies stigma/embarrassment as intervention barriers (Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010; Hinshaw, 2005; Martin et al., 2007; Wiener et al., 2012). Of note, neither self-reported experience with the academic ADHD intervention (for all respondents) nor personal special education service experience (for students and their parents), related to expressed willingness to use academic interventions. No research could be identified that addressed the role of past experience in academic ADHD intervention receptivity. Studies examining ADHD intervention acceptability in the health sector yield inconsistent results on whether experienced users are more or less accepting of various ADHD treatments (for a review, see Brinkman & Epstein, 2011).

Expressed Concerns

The qualitative analysis results of expressed intervention concerns added valuable insights to the survey findings. Whereas the quantitative survey results clearly pinpointed adolescents’ low receptivity toward ADHD interventions, the qualitative analysis provided additional information to explain such reluctance, identifying concerns over interventions’ potential to disrupt the academic environment, cause stigma for recipients and create intervention dependence. These concerns appear to highlight the need to include basic education about the nature of ADHD into any intervention plan, because students with ADHD are frequently perceived as disruptive and experience peer rejection (Mrug et al., 2012), as a function of their associated symptomology, rather than due to academic interventions they receive.

In addition, the qualitative analysis identified an unanticipated feasibility barrier, namely, concerns about the equality and fairness of individualized student focused academic interventions. Considering that academic interventions are intended to “level the playing field” for students with special needs, the concerns about potential “unfairness” of ADHD interventions raise intriguing questions. It remains unclear whether inequality concerns are a reflection of ADHD’s status as a hidden disability, which is still considered controversial and perhaps less valid than other disabilities (e.g., Visser & Jehan, 2009). The quantitative survey did not include corresponding questions, because literature reviews at the time of survey development did not identify equality/fairness perceptions as potential barriers to ADHD interventions.

Implications for Practice

Implications for practice based on our data point more to the need to address common misconceptions than to alter or discard specific academic interventions. Specifically, youth identified that individualized academic interventions for students with ADHD were viewed as (a) potentially disruptive to the academic environment, (b) a cause of stigma for recipients, (c) creating intervention dependence, and (d) fostering views of inequitable treatment of students. As such, efforts to increase the acceptability of ADHD interventions should focus on educating students with and without ADHD, as well as key adults (e.g., parents, teachers, health professionals), on the nature of interventions and the fundamental importance of individualization in education. Information is particularly critical in light of the current emphasis on early intervention and RTI, as well as longstanding IDEA regulations that ensure students receive the academic support necessary to access the general education curriculum and succeed (Gagnon, Murphy, Steinberg, Gaddis, & Crockett, 2013).

Results also indicate that adolescent experience with ADHD-related academic interventions, through general education interventions or special education does not alter these youths’ perceptions of related stigma. This finding underscores the notion that experience with an intervention is insufficient to alter youth views and increase acceptability. There is a need to explain and dialogue with students with ADHD and classmates to provide more in-depth understanding issues, such as how interventions “level the playing field,” rather than provide an unfair advantage to youth with ADHD.

Implications for Research

The current study provides an initial understanding of stakeholder and student views toward common academic interventions for youth with ADHD. A few implications for future research are noteworthy. First, research on academic interventions should include representation of adolescents’ perspectives. Information could be effectively solicited, for example, through use of mixed-methods research designs that elicit input via individual interviews and focus groups (Collins, Onwuegbuzie, & Sutton, 2006). Furthermore, it is necessary to move beyond merely soliciting adolescent views of intervention feasibility, but to also obtain their views of ways that perceived stigma might be avoided or overcome.

Future research is also needed to address the concerning absence of validated training programs for stakeholders and students that promote an understanding and appreciation for academic-related ADHD interventions (Byrd, 2011). Whereas previous studies documented the need to increase teacher ADHD knowledge (Kos, Richdale, & Hay, 2006), our study findings go a step further and suggest teachers also need concrete skills enhancement to integrate academic interventions as a regular part of classroom activities. However, we also need approaches that will contribute toward stigma reduction, enhanced confidentiality, and discretion (i.e., making interventions socially less obvious).

Limitations

Several important study limitations must be acknowledged. The academic interventions were chosen by a process that included qualitative methods (e.g., sequence of experience sampling and focus groups), review of health sector ADHD practice guidelines and practice parameters, review of educational interventions and accommodations for ADHD, and survey pilot testing. However, limited empirical proof of intervention efficacy, despite their use, is a concern. Other limitations arise from sampling, geographic generalizability, and selections in participation rates. The study sample represents a Southeastern U.S. school district and, due to limited school district demographic diversity, includes only Caucasian and African American adolescents. Findings are further limited by the occasional brevity of open-ended responses. The interpretation of some qualitative responses could have benefitted from additional background information. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, the current study provides new and important findings concerning usability and feasibility of academic interventions for youth with ADHD.

Conclusion

Study findings support the IES emphasis on raising usability and feasibility during intervention development and implementation (IES, 2012). It is critically important to consider adolescents’ viewpoints to avoid interventions perceived as acceptable by adults, but resented or resisted by adolescents. It is through the combination of providing empirically validated academic interventions and ensuring student acceptability that potential impact of interventions for youth with ADHD will be realized.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by NIMH R01MH57399 grant.

Biographies

Regina Bussing is a professor in the Departments of Psychiatry, Pediatrics and Clinical and Health Psychology at the University of Florida. She received her MD from the Justus Liebig University in Giessen, Germany, and her public health degree from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mirka Koro-Ljungberg is a professor of qualitative research methodology at the University of Florida. Her research and publications focus on various theoretical and methodological aspects of qualitative inquiry, participant-driven methodologies, and cultural critique.

Joseph Calvin Gagnon is an associate professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Florida. He received his PhD degree from the University of Maryland.

Dana M. Mason is a research coordinator at the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Florida. She received her BS degree in psychology from the University of Florida and has coordinated numerous treatment studies with pediatric and adult patients.

Anne Ellison is currently an Assistant Professor at the University of South Carolina-Aiken (USCA) and Professor Emerita at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is teaching in the Clinical Psychology Master’s program at USCA, and is continuing her research program exploring emotional self-regulation in individuals with ADHD.

Kenji Noguchi is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Southern Mississippi. He received his PhD degree from the University of Mississippi.

Cynthia W. Garvan is research associate professor at the College of Nursing at the University of Florida. She received her PhD degree in statistics from the University of Florida.

Dolores Albarracin is the Martin Fishbein Professor at the Annenberg School of Communication and Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. She received her PhD in Social Psychology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: Treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1033–1044. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin N, Ehle C, Vinas V. Physical exercise as a reinforcer to promote calmness of an ADHD child. Behavior Modification. 2006;30:564–570. doi: 10.1177/0145445504267952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell L, Long S, Garvan C, Bussing R. The impact of teacher credentials on ADHD stigma perceptions. Psychology in the Schools. 2011;48:184–197. doi: 10.1002/Pits.20536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt SE, Thurlow ML. Five of the most frequently allowed testing accommodations in state policy. Remedial and Special Education. 2004;25:141–152. doi: 10.1177/07419325040250030201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Epstein JN. Treatment planning for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Treatment utilization and family preferences. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2011;5:45–56. doi: 10.2147/Ppa.S10647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant A, Charmaz K. The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. London, England: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant DP, Bryant BR, Gersten R, Scammacca N, Chavez M. Mathematics intervention for first- and second-grade students with mathematics difficulties: The effects of Tier 2 intervention delivered as booster lessons. Remedial and Special Education. 2008;29:20–32. doi: 10.1177/0741932507309712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg M, Noguchi K, Mason D, Mayerson G, Garvan CW. Willingness to use ADHD treatments: A mixed methods study of perceptions by adolescents, parents, health professionals and teachers. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.soc-scimed.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Mason DM, Bell L, Porter P, Garvan C. Adolescent outcomes of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a diverse community sample [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Porter P, Zima BT, Mason D, Garvan CW, Reid R. Academic outcome trajectories of students with ADHD: Does exceptional education status matter? Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2010;20:131–143. doi: 10.1177/1063426610388180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd ES. Educating and involving parents in the response to intervention process: The school’s important role. TEACHING Exceptional Children. 2011;43:32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chew BL, Jensen SA, Rosen LA. College students’ attitudes toward their ADHD peers. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2009;13:271–276. doi: 10.1177/1087054709333347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins KT, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Sutton IL. A model incorporating the rationale and purpose for conducting mixed-methods research in special education and beyond. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal. 2006;4:67–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) In: Cooley M, editor. Teaching kids with mental health and learning disorders in the regular classroom: How to recognize, understand, and help challenged (and challenging) students succeed. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit; 2007. pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown RE. Prevalence and correlates of ADHD symptoms in the national health interview survey. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2005;9:392–401. doi: 10.1177/1087054705280413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DF, Pisecco S, Hamilton RJ, Moore DW. Teacher perceptions of classroom interventions for children with ADHD: A cross-cultural comparison of teachers in the United States and New Zealand. School Psychology Quarterly. 2006;21:171–196. doi: 10.1521/scpq.2006.21.2.171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- deBettencourt LU. Understanding the differences between IDEA and Section 504. TEACHING Exceptional Children. 2002;34:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ. School-based interventions for students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Current status and future directions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Weyandt LL, Janusis GM. ADHD in the classroom: Effective intervention strategies. Theory Into Practice. 2011;50:35–42. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2011.534935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon JC, Maccini P, Haydon T. Assessment and accountability in public and private secondary day treatment and residential schools for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Special Education Leadership. 2011;24:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon JC, Murphy K, Steinberg M, Gaddis J, Crockett J. IDEA-related professional development in juvenile corrections schools. Journal of Special Education Leadership. 2013;26:93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Griffiths K, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. Article 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: Developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs [Review] Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:714–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social class. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act. Pub. L. No. 108–446. (2004).

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act Regulations. 34 C.F.R. § 300.1 et seq. (2006).

- Institute of Education Sciences. Request for applications: Special education research grants. Washington, DC: Author; 2012. CFDA Number: 84.324A. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Hommersen P, Seipp C. Acceptability of behavioral and pharmacological treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Relations to child and parent characteristics [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos J, Richdale A, Hay D. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and their teachers: A review of the literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2006;53:147–160. doi: 10.1080/10349120600716125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krain AL, Kendall PC, Power TJ. The role of treatment acceptability in the initiation of treatment for ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2005;9:425–434. doi: 10.1177/1087054705279996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Epstein JN, Urbanowicz CM, Simon JO, Graham AJ. Efficacy of an organization skills intervention to improve the academic functioning of students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:407–417. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.3.407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski LJ, Lovett BJ, Rogers CL. Extended time as a testing accommodation for students with reading disabilities: Does a rising tide lift all ships? Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2008;26:315–324. doi: 10.1177/0734282908315757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Pescosolido BA, Olafsdottir S, McLeod JD. The construction of fear: Americans’ preferences for social distance from children and adolescents with mental health problems [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:50–67. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal RE, Roberts MC, Barone VJ. Mothers’ and children’s perceptions of medication for children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2000;30:173–187. doi: 10.1023/A:1021347621455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Smith BH, Pelham WE., Jr Development of a school-wide behavior program in a public middle school: An illustration of deployment-focused intervention development, stage 1. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2005;9:333–342. doi: 10.1177/1087054705279301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Jensen PS, … Houck PR. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:484–500. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Molina BS, Hoza B, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman L, Arnold LE. Peer rejection and friendships in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Contributions to long-term outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1013–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9610-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Goldfine ME, Evangelista NM, Hoza B, Kaiser NM. A critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD [Review] Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:335–351. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Jensen PS, Martin JK, Perry BL, Olafsdottir S, Fettes D. Public knowledge and assessment of child mental health problems: Findings from the National Stigma Study-Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:339–349. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318160e3a0. S0890-8567(09)62317-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka S. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [Practice Guideline Review] Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:894–921. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–948. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.942. 164/6/942 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggi VL, Chronis AM. Interventions to address the academic impairment of children and adolescents with ADHD. Clinical and Child Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:85–111. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS® 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schnoes C, Reid R, Wagner M, Marder C. ADHD among students receiving special education services: A national survey. Exceptional Children. 2006;72:483–496. [Google Scholar]

- Stalvey S, Brasell H. Using stress balls to focus the attention of sixth-grade learners. The Journal of At-Risk Issues. 2006;12:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Trout AL, Lienemann TO, Reid R, Epstein MH. A review of non-medication interventions to improve the acedemic performance of children and youth with ADHD. Remedial and Special Education. 2007;4:207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Visser J, Jehan Z. ADHD: A scientific fact or a factual opinion? A critique of the veracity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2009;14:127–140. doi: 10.1080/13632750902921930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener J, Malone M, Varma A, Markel C, Biondic D, Tannock R, Humphries T. Children’s perceptions of their ADHD symptoms: Positive illusions, attributions, and stigma. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 2012;27:217–242. doi: 10.1177/0829573512451972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]