Abstract

Today’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth come out at younger ages, and public support for LGBT issues has dramatically increased, so why do LGBT youth continue to be at high risk for compromised mental health? We provide an overview of the contemporary context for LGBT youth, followed by a review of current science on LGBT youth mental health. Research in the past decade has identified risk and protective factors for mental health, which point to promising directions for prevention, intervention, and treatment. Legal and policy successes have set the stage for advances in programs and practices that may foster LGBT youth mental health. Implications for clinical care are discussed, and important areas for new research and practice are identified.

Keywords: LGBT, sexual orientation, gender identity, youth

INTRODUCTION

In the period of only two decades, there has been dramatic emergence of public and scientific awareness of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) lives and issues. This awareness can be traced to larger sociocultural shifts in understandings of sexual and gender identities, including the emergence of the “gay rights” movement in the 1970s and the advent of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. Yet the first public and research attention to young LGBTs focused explicitly on mental health: A small number of studies in the 1980s began to identify concerning rates of reported suicidal behavior among “gay” youth, and a US federal report on “gay youth suicide” (Gibson 1989) became controversial in both politics and research (Russell 2003). During the past two decades there have been not only dramatic shifts in public attitudes toward LGBT people and issues (Gallup 2015), but also an emergence of research from multiple and diverse fields that has created what is now a solid foundation of knowledge regarding mental health in LGBT youth.

LGBT is an acronym used to refer to people who select those sexual or gender identity labels as personally meaningful for them, and sexual and gender identities are complex and historically situated (Diamond 2003, Rosario et al. 1996, Russell et al. 2009). Throughout this article, we use the acronym LGBT unless in reference to studies of subpopulations. Most of the knowledge base has focused on sexual identities (and historically mostly on gay and lesbian identities), with much less empirical study of mental health among transgender or gender-nonconforming youth. Sexual identities are informed by individuals’ romantic, sexual, or emotional attractions and behaviors, which may vary within persons (Rosario et al. 2006, Saewyc et al. 2004). Further, the meanings of LGBT and the experiences of LGBT people must be understood as intersecting with other salient personal, ethnic, cultural, and social identities (Consolacion et al. 2004, Kuper et al. 2014). An important caveat at the outset of this article is that much of the current knowledge base will be extended in coming decades to illuminate how general patterns of LGBT youth mental health identified to date are intersectionally situated, that is, how patterns of mental health may vary across not only sexual and gender identities, but also across racial and ethnic, cultural, and social class identities as well.

In this article, we review mental health in LGBT youth, focusing on both theoretical and empirical foundations of this body of research. We consider the state of knowledge of risk and protective factors, focusing on those factors that are specific to LGBT youth and their experiences as well as on those that are amenable to change through prevention or intervention. The conclusion considers legal, policy, and clinical implications of the current state of research. First, we provide context for understanding the lives of contemporary LGBT youth.

UNDERSTANDING CONTEMPORARY LGBT YOUTH

We begin by acknowledging a paradox or tension that underlies public discourse of LGBT youth and mental health. On the one hand there have been dramatic social changes regarding societal acceptance of LGBT people and issues, and yet on the other hand there has been unprecedented concern regarding LGBT youth mental health. If things are so much “better,” why are mental health concerns for LGBT youth urgent?

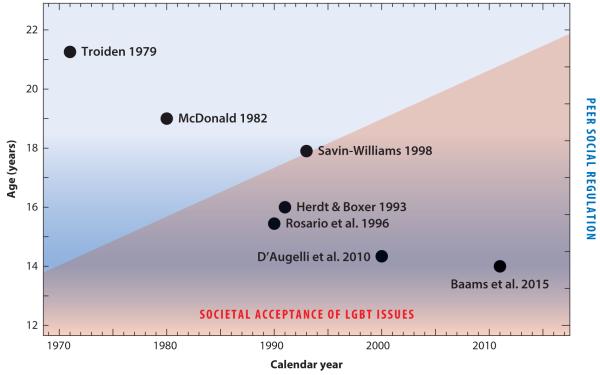

Historical trends in social acceptance in the United States show, for example, that 43% of US adults agreed that “gay or lesbian relations between consenting adults should be legal” in 1977; by 2013 that number had grown to 66% (Gallup 2015). The pace of change in the United States and around the world has been dramatic: The first country to recognize marriage between same-sex couples was the Netherlands in 2001; as of this writing, 22 countries recognize marriage for same-sex couples. The pink shaded area in Figure 1 (along the x-axis) illustrates this change in the increasing social acceptance of LGBT people across historical time. Seemingly orthogonal to this trend is the decreasing average age at which LGBT youth “come out” or disclose their sexual or gender identities to others (Floyd & Bakeman 2006). This is illustrated with data on the average ages of first disclosure or coming out (the y-axis in Figure 1) taken from empirical studies of samples of LGB persons. Data from samples collected since 2000 show an average age of coming out at around 14 (D’Augelli et al. 2010), whereas a decade before, the average age of coming out was approximately 16 (Rosario et al. 1996, Savin-Williams 1998), and a study from the 1970s recorded coming out at an average age of 20 (Troiden 1979). Although they appear orthogonal, the trends are complementary: Societal acceptance has provided the opportunity for youth to understand themselves in relation to the growing public visibility of LGBT people.

Figure 1.

Historical trends in societal attitudes, age trends in peer attitudes, and the decline in ages at which lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth come out. Circles (with associated publication references) indicate approximate average ages of first disclosure in samples of LGB youth at the associated historical time when the studies were conducted.

Contrast these trends with developmental patterns in child and adolescent interpersonal relations and social regulation, represented by blue shading in Figure 1. The early adolescent years are characterized by heightened self- and peer regulation regarding (especially) gender and sexuality norms (Mulvey & Killen 2015, Pasco 2011). During adolescence, youth in general report stronger prejudicial attitudes and more frequent homophobic behavior at younger ages (Poteat & Anderson 2012). Young adolescents may be developmentally susceptible to social exclusion behavior and attitudes, whereas older youth are able to make more sophisticated evaluative judgments regarding human rights, fairness, and prejudice (e.g., Horn 2006, Nesdale 2001). Therefore, today’s LGBT youth typically come out during a developmental period characterized by strong peer influence and opinion (Brechwald & Prinstein 2011, Steinberg & Monahan 2007) and are more likely to face peer victimization when they come out (D’Augelli et al. 2002, Pilkington & D’Augelli 1995). Such victimization has well-documented psychological consequences (Birkett et al. 2009, Poteat & Espelage 2007, Russell et al. 2014).

In sum, changes in societal acceptance of LGBT people have made coming out possible for contemporary youth, yet the age of coming out now intersects with the developmental period characterized by potentially intense interpersonal and social regulation of gender and sexuality, including homophobia. Given this social/historical context, and despite increasing social acceptance, mental health is a particularly important concern for LGBT youth.

MENTAL HEALTH IN LGBT YOUTH

To organize our review, we start by briefly presenting the historical and theoretical contexts of LGBT mental health. Next, we provide an overview of the prevalence of mental health disorders among LGBT youth in comparison to the general population, and various psychosocial characteristics (i.e., structural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal) that place LGBT youth at risk for poor mental health. We then highlight studies that focus on factors that protect and foster resilience among LGBT youth.

Prior to the 1970s, the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) listed homosexuality as a “sociopathic personality disturbance” (Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1952). Pioneering studies on the prevalence of same-sex sexuality (Ford & Beach 1951; Kinsey et al. 1948, 1953) and psychological comparisons between heterosexual and gay men (Hooker 1957) fostered a change in attitudes from the psychological community and motivated the APA’s removal of homosexuality as a mental disorder in 1973 (although all conditions related to same-sex attraction were not removed until 1987). Over the past 50 years, the psychological discourse regarding same-sex sexuality shifted from an understanding that homosexuality was intrinsically linked with poor mental health toward understanding the social determinants of LGBT mental health. Recent years have seen similar debates about the diagnoses related to gender identity that currently remain in the DSM (see sidebar Changes in Gender Identity Diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

Minority stress theory (Meyer 1995, 2003) has provided a foundational framework for understanding sexual minority mental health disparities (Inst. Med. 2011). It posits that sexual minorities experience distinct, chronic stressors related to their stigmatized identities, including victimization, prejudice, and discrimination. These distinct experiences, in addition to everyday or universal stressors, disproportionately compromise the mental health and well-being of LGBT people. Generally, Meyer (2003) posits three stress processes from distal to proximal: (a) objective or external stressors, which include structural or institutionalized discrimination and direct interpersonal interactions of victimization or prejudice; (b) one’s expectations that victimization or rejection will occur and the vigilance related to these expectations; and (c) the internalization of negative social attitudes (often referred to as internalized homophobia). Extensions of this work also focus on how intrapersonal psychological processes (e.g., appraisals, coping, and emotional regulation) mediate the link between experiences of minority stress and psychopathology (see Hatzenbuehler 2009). Thus, it is important to recognize the structural circumstances within which youth are embedded and that their interpersonal experiences and intrapersonal resources should be considered as potential sources of both risk and resilience.

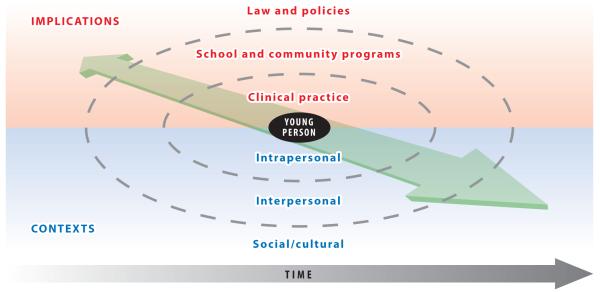

We illustrate multilevel ecological contexts in Figure 2. The young person appears as the focus, situated in the center and defined by intrapersonal characteristics. This is surrounded by interpersonal contexts (which, for example, include daily interactions with family and peers) that exist within social and cultural contexts. The arrow along the bottom of the figure suggests the historically changing nature of the contexts of youth’s lives. Diagonal arrows that transverse the figure acknowledge interactions across contexts, and thus implications for promoting LGBT youth mental health at the levels of policy, community, and clinical practice, which we consider at the end of the manuscript. We use this model to organize the following review of LGBT youth mental health.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of contextual influences on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth mental health and associated implications for policies, programs, and practice. The arrow along the bottom of the figure indicates the historically changing nature of the contexts of youth’s lives. Diagonal arrows acknowledge interactions across contexts, thus recognizing opportunities for promoting LGBT youth mental health at policy, community, and clinical practice levels.

Prevalence of Mental Health Problems Among LGBT Youth

Adolescence is a critical period for mental health because many mental disorders show onset during and directly following this developmental period (Kessler et al. 2005, 2007). Recent US estimates of adolescent past-year mental health diagnoses indicate that 10% demonstrate a mood disorder, 25% an anxiety disorder, and 8.3% a substance use disorder (Kessler et al. 2012). Further, suicide is the third leading cause of death for youth ages 10 to 14 and the second leading cause of death for those ages 15 to 24 (CDC 2012).

The inclusion of sexual attraction, behavior, and identity measures in population-based studies (e.g., the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health and the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System) has greatly improved knowledge of the prevalence of LGB mental health disparities and the mechanisms that contribute to these inequalities for both youth and adults; there remains, however, a critical need for the development and inclusion of measures to identify transgender people, which thwarts more complete understanding of mental health among transgender youth. Such data illustrate overwhelming evidence that LGB persons are at greater risk for poor mental health across developmental stages. Studies using adult samples indicate elevated rates of depression and mood disorders (Bostwick et al. 2010, Cochran et al. 2007), anxiety disorders (Cochran et al. 2003, Gilman et al. 2001), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2009a), alcohol use and abuse (Burgard et al. 2005), and suicide ideation and attempts, as well as psychiatric comorbidity (Cochran et al. 2003, Gilman et al. 2001). Studies of adolescents trace the origins of these adult sexual orientation mental health disparities to the adolescent years: Multiple studies demonstrate that disproportionate rates of distress, symptomatology, and behaviors related to these disorders are present among LGBT youth prior to adulthood (Fish & Pasley 2015, Needham 2012, Ueno 2010).

US and international studies consistently conclude that LGBT youth report elevated rates of emotional distress, symptoms related to mood and anxiety disorders, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior when compared to heterosexual youth (Eskin et al. 2005, Fergusson et al. 2005, Fleming et al. 2007, Marshal et al. 2011), and that compromised mental health is a fundamental predictor of a host of behavioral health disparities evident among LGBT youth (e.g., substance use, abuse, and dependence; Marshal et al. 2008). In a recent meta-analysis, Marshal et al. (2011) reported that sexual minority youth were almost three times as likely to report suicidality; these investigators also noted a statistically moderate difference in depressive symptoms compared to heterosexual youth.

Despite the breadth of literature highlighting disparities in symptoms and distress, relatively lacking are studies that explore the presence and prevalence of mental health disorders or diagnoses among LGBT youth. Using a birth cohort sample of Australian youth 14 to 21 years old, Fergusson and colleagues (1999) found that LGB youth were more likely to report suicidal thoughts or attempts, and experienced more major depression, generalized anxiety disorders, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbid diagnoses, compared to heterosexual youth. Results from a more recent US study that interviewed a community sample of LGBT youth ages 16 to 20 indicated that nearly one-third of participants met the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder and/or reported a suicide attempt in their lifetime (Mustanski et al. 2010). When comparing these findings to mental health diagnosis rates in the general population, the difference is stark: Almost 18% of lesbian and gay youth participants met the criteria for major depression and 11.3% for PTSD in the previous 12 months, and 31% of the LGBT sample reported suicidal behavior at some point in their life. National rates for these diagnoses and behaviors among youth are 8.2%, 3.9%, and 4.1%, respectively (Kessler et al. 2012, Nock et al. 2013).

Studies also show differences among LGB youth. For example, studies on LGB youth suicide have found stronger associations between sexual orientation and suicide attempts for sexual minority males comparative to sexual minority females (Fergusson et al. 2005, Garofalo et al. 1999), including a meta-analysis using youth and adult samples (King et al. 2008). Conversely, lesbian and bisexual female youth are more likely to exhibit substance use problems when compared to heterosexual females (Needham 2012, Ziyadeh et al. 2007) and sexual minority males (Marshal et al. 2008); however, some reports on longitudinal trends indicate that these differences in disparities diminish over time because sexual minority males “catch up” and exhibit faster accelerations of substance use in the transition to early adulthood (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2008a).

Although not explicitly tested in all studies, results often indicate that bisexual youth (or those attracted to both men and women) are at greater risk for poor mental health when compared to heterosexual and solely same-sex-attracted counterparts (Marshal et al. 2011, Saewyc et al. 2008, Talley et al. 2014). In their meta-analysis, Marshal and colleagues (2011) found that bisexual youth reported more suicidality than lesbian and gay youth. Preliminary research also suggests that youth questioning their sexuality report greater levels of depression than those reporting other sexual identities (heterosexual as well as LGB; Birkett et al. 2009) and show worse psychological adjustment in response to bullying and victimization than heterosexual or LGB-identified students (Poteat et al. 2009).

Relatively lacking is research that explicitly tests racial/ethnic differences in LGBT youth mental health. As with general population studies, researchers have observed mental health disparities across sexual orientation within specific racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Borowsky et al. 2001). Consolacion and colleagues (2004) found that among African American youth, those who were same-sex attracted had higher rates of suicidal thoughts and depressive symptoms and lower levels of self-esteem than their African American heterosexual peers, and Latino same-sex-attracted youth were more likely to report depressive symptoms than Latino heterosexual youth.

Even fewer are studies that simultaneously assess the interaction between sexual orientation and racial/ethnic identities (Inst. Med. 2011), especially among youth. One study assessed differences between white and Latino LGBQ youth (Ryan et al. 2009) and found that Latino males reported more depression and suicidal ideation compared to white males, whereas rates were higher for white females compared to Latinas. Although not always in relation to mental health outcomes, researchers discuss the possibility of cumulative risk as the result of managing multiple marginalized identities (Díaz et al. 2006, Meyer et al. 2008). However, some empirical evidence suggests the contrary: that black sexual minority male youth report better psychological health (fewer major depressive episodes and less suicidal ideation and alcohol abuse or dependence) than their white sexual minority male counterparts (Burns et al. 2015). Still other studies find no racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of mental health disorders and symptoms within sexual minority samples (Kertzner et al. 2009, Mustanski et al. 2010).

In summary, clear and consistent evidence indicates that global mental health problems are elevated among LGB youth, and similar results are found for the smaller number of studies that use diagnostic criteria to measure mental health. Among sexual minorities, there are preliminary but consistent indications that bisexual youth are among those at higher risk for mental health problems. The general dearth of empirical research on gender and racial/ethnic differences in mental health status among LGBT youth, as well as contradictory findings, indicates the need for more research. Specific research questions and hypotheses aimed at understanding the intersection of multiple (minority) identities are necessary to better understand diversity in the lived experiences of LGBT youth and their potentials for risk and resilience in regard to mental health and well-being (Russell 2003, Saewyc 2011).

Risk Factors

Two approaches are often used to frame and explore mechanisms that exacerbate risk for LGBT youth (Russell 2005, Saewyc 2011). First is to examine the greater likelihood of previously identified universal risk factors (those that are risk factors for all youth), such as family conflict or child maltreatment; LGBT youth score higher on many of the critical universal risk factors for compromised mental health, such as conflict with parents and substance use and abuse (Russell 2003). The second approach explores LGBT-specific factors such as stigma and discrimination and how these compound everyday stressors to exacerbate poor outcomes. Here we focus on the latter and discuss prominent risk factors identified in the field—the absence of institutionalized protections, biased-based bullying, and family rejection—as well as emerging research on intrapersonal characteristics associated with mental health vulnerability.

At the social/cultural level, the lack of support in the fabric of the many institutions that guide the lives of LGBT youth (e.g., their schools, families, faith communities) limits their rights and protections and leaves them more vulnerable to experiences that may compromise their mental health. To date, only 19 states and the District of Columbia have fully enumerated antibullying laws that include specific protections for sexual and gender minorities (GLSEN 2015), despite the profound effects that these laws have on the experiences of youth in schools (e.g., Hatzenbuehler et al. 2014). LGBT youth in schools with enumerated nondiscrimination or antibullying policies (those that explicitly include actual or perceived sexual orientation and gender identity or expression) report fewer experiences of victimizations and harassment than those who attend schools without these protections (Kosciw et al. 2014). As a result, lesbian and gay youth living in counties with fewer sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI)-specific antibullying policies are twice as likely to report past-year suicide attempts than youth living in areas where these policies were more commonplace (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes 2013).

Along with school environments, it is also important to consider youths’ community context. LGBT youth who live in neighborhoods with a higher concentration of LGBT-motivated assault hate crimes also report greater likelihood of suicidal ideation and attempts than those living in neighborhoods that report a low concentration of these offenses (Duncan & Hatzenbuehler 2014). Further, studies show that youth who live in communities that are generally supportive of LGBT rights [i.e., those with more protections for same-sex couples, greater number of registered Democrats, presence of gay-straight alliances (GSAs) in schools, and SOGI-specific nondiscrimination and antibullying policies] are less likely to attempt suicide even after controlling for other risk indicators, such as a history of physical abuse, depressive symptomatology, drinking behaviors, and peer victimization (Hatzenbuehler 2011). Such findings demonstrate that pervasive LGBT discrimination at the broader social/cultural level and the lack of institutionalized support have direct implications for the mental health and well-being of sexual minority youth.

At the interpersonal level, an area that has garnered new attention is the distinct negative effect of biased-based victimization compared to general harassment (Poteat & Russell 2013). Researchers have demonstrated that biased-based bullying (i.e., bullying or victimization due to one’s perceived or actual identities including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, and disability status) amplifies the effects of victimization on negative outcomes. When compared to non-biased-based victimization, youth who experience LGB-based victimization report higher levels of depression, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, substance use, and truancy (Poteat et al. 2011, Russell et al. 2012a), regardless of whether these experiences are in person or via the Internet (Sinclair et al. 2012). Retrospective reports of biased-based victimization are also related to psychological distress and overall well-being in young adulthood, suggesting that these experiences in school carry forward to later developmental stages (Toomey et al. 2011). Importantly, although rates of bullying decrease over the course of the adolescent years, this trend is less pronounced for gay and bisexual compared to heterosexual males, leaving these youth vulnerable to these experiences for longer periods of time (Robinson et al. 2013). Further, these vulnerabilities to SOGI-biased-based bullying are not unique to LGBT youth: Studies also indicate that heterosexual youth report poor mental and behavioral health as the result of homophobic victimization (Poteat et al. 2011, Robinson & Espelage 2012). Thus, strategies to reduce discriminatory bullying will improve well-being for all youth, but especially those with marginalized identities.

Positive parental and familial relationships are crucial for youth well-being (Steinberg & Duncan 2002), but many LGBT youth fear coming out to parents (Potoczniak et al. 2009, Savin-Williams & Ream 2003) and may experience rejection from parents because of these identities (D’Augelli et al. 1998, Ryan et al. 2009). This propensity for rejection is evidenced in the disproportionate rates of LGBT homeless youth in comparison to the general population (an estimated 40% of youth served by drop-in centers, street outreach programs, and housing programs identify as LGBT; Durso & Gates 2012). Although not all youth experience family repudiation, those who do are at greater risk for depressive symptoms, anxiety, and suicide attempts (D’Augelli 2002, Rosario et al. 2009). Further, those who fear rejection from family and friends also report higher levels of depression and anxiety (D’Augelli 2002). In an early study of family disclosure, D’Augelli and colleagues (1998) found that compared to those who had not disclosed, youth who had told family members about their LGB identity often reported more verbal and physical harassment from family members and experiences of suicidal thoughts and behavior. More recently, Ryan and colleagues (2009) found that compared to those reporting low levels of family rejection, individuals who experienced high levels of rejection were dramatically more likely to report suicidal ideation, to attempt suicide, and to score in the clinical range for depression.

Finally, some youth may have fewer intrapersonal skills and resources to cope with minority stress experiences or may develop maladaptive coping strategies as a result of stress related to experiences of discrimination and prejudice (Hatzenbuehler 2009, Meyer 2003). Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2008b) found that same-sex-attracted adolescents were more likely to ruminate and demonstrated poorer emotional awareness compared to heterosexual peers; this lack of emotion regulation was associated with later symptoms of depression and anxiety. Similarly, LGB youth were more likely to experience rumination and suppress emotional responses on days that they experienced minority stressors such as discrimination or prejudice, and these maladaptive coping behaviors, including rumination, were related to greater levels of psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2008b).

A solid body of research has identified LGBT youth mental health risk factors at both the structural or societal levels as well as in interpersonal interactions with family and peers when they are characterized by minority stress. Less attention has focused on intrapersonal characteristics of LGB youth that may be accentuated by minority stress, but several new studies show promising results for identifying vulnerability as well as strategies for clinical practice.

Protective Factors

Despite adversity, most LGBT youth develop into healthy and productive adults (Russell & Joyner 2001, Saewyc 2011), yet research has focused predominantly on risk compared to protective factors or resilience (Russell 2005). Here we discuss contextual factors that affirm LGBT youths’ identities, including school policies and programs, family acceptance, dating, and the ability to come out and be out.

Studies clearly demonstrate the benefit of affirming and protective school environments for LGBT youth mental health. Youth living in states with enumerated antibullying laws that include sexual orientation and gender identity report less homophobic victimization and harassment than do students who attend schools in states without these protections (Kosciw et al. 2014). Further, mounting evidence documents the supportive role of GSAs in schools (Poteat et al. 2012, Toomey et al. 2011). GSAs are school-based, student-led clubs open to all youth who support LGBT students; GSAs aim to reduce prejudice and harassment within the school environment (Goodenow et al. 2006). LGBT students in schools with GSAs and SOGI resources often report feeling safer and are less likely to report depressive symptom, substance use, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in comparison with students in schools lacking such resources (Goodenow et al. 2006, Hatzenbuehler et al. 2014, Poteat et al. 2012). The benefits of these programs are also seen at later developmental stages: Toomey and colleagues (2011) found that youth who attended schools with GSAs, participated in a GSA, and perceived that their GSA encouraged safety also reported better psychological health during young adulthood. Further, these experiences with GSAs diminished some of the negative effects of LGBT victimization on young adult well-being.

Along with studies that highlight the benefits of enumerative policies and GSAs, research also demonstrates that LGBT-focused policy and inclusive curriculums are associated with better psychological adjustment for LGBT students (Black et al. 2012). LGBT-inclusive curriculums introduce specific historical events, persons, and information about the LGBT community into student learning (Snapp et al. 2015a,b) and have been shown to improve students’ sense of safety (Toomey et al. 2012) and feelings of acceptance (GLSEN 2011) and to reduce victimization in schools (Kosciw et al. 2012). Further, LGBT-specific training for teachers, staff, and administrators fosters understanding and empathy for LGBT students and is associated with more frequent adult intervention in biased-based bullying (Greytak et al. 2013, Greytak & Kosciw 2014). Beyond formal school curriculum and clubs, recent studies document the ways that such school strategies influence interpersonal relationships within schools through supportive peers and friends. For example, Poteat (2015) found that youth who engage in more LGBT-based discussions with peers and who have LGBT friends are more likely to participate in LGBT-affirming behavior and intervene when hearing homophobic remarks (see also Kosciw et al. 2012).

At the interpersonal level, studies of LGBT youth have consistently shown that parental and peer support are related to positive mental health, self-acceptance, and well-being (Sheets & Mohr 2009, Shilo & Savaya 2011). D’Augelli (2003) found that LGB youth who retained friends after disclosing their sexual identity had higher levels of self-esteem, lower levels of depressive symptomatology, and fewer suicidal thoughts than those who had lost friends as a result of coming out. Similarly, LGB youth who reported having sexual minority friends experienced less depression over time, and the presence of LGB friends attenuated the effects of victimization (Ueno 2005). Noteworthy is support specifically related to and affirming one’s sexual orientation and gender identity, which appears to be especially beneficial for youth (compared to general support; Doty et al. 2010, Ryan et al. 2010). Snapp and colleagues (2015c) found that sexuality-related social support from parents, friends, and community during adolescence each uniquely contributed to positive well-being in young adulthood, with parental support providing the most benefit. Unfortunately, many LGBT youth report lower levels of sexuality-specific support in comparison to other forms of support, especially from parents (Doty et al. 2010), and transgender youth report lower social support from parents than their sexual minority counterparts (Ryan et al. 2010). Studies that explicitly explore the benefits of LGB-specific support show that sexuality-specific support buffers the negative effects of minority stressors (Doty et al. 2010, Rosario et al. 2009). For example, Ryan et al. (2010) found that parents’ support of sexual orientation and gender expression was related to higher levels self-esteem, less depression, and fewer reports of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts.

Romantic relationships are understood as normative and important developmental experiences for adolescents (Collins et al. 2009), but LGBT youth may experience a number of social barriers related to dating same-sex partners that may have implications for their development during adolescence and at later stages of the life course (Frost 2011, Mustanski et al. 2014, Russell et al. 2012b). These barriers include potentially limited access to romantic partners, minority stressors specific to pursuing relationships with same-sex partners, and the restriction of same-sex romantic behavior in educational settings. These obstacles, in turn, can steer youth to other social settings, such as bars and clubs, that may increase risk for poor health and health behavior (Mustanski et al. 2014). LGB youth report more fear and less agency in finding suitable romantic partners and dating in general (Diamond & Lucas 2004). Yet findings demonstrate that dating same-sex partners is related to improved mental health and lower substance use behavior for LGB youth (Russell & Consolacion 2003, Russell et al. 2002). Results from a three-year longitudinal study showed that in comparison to LGB youth who dated other-sex partners, those who dated same-sex partners experienced an increase in self-esteem and a decrease in internalized homophobia for men and women, respectively (Bauermeister et al. 2010). In a more recent study, Baams and colleagues (2014) found that the presence of a romantic partner buffered the effects of minority stress on the psychological well-being of same-sex-attracted youth.

Finally, coming out as LGBT involves dynamic interplay between intrapersonal development and interpersonal interaction and disclosure. Research consistently shows that coming out puts youth at greater risk for verbal and physical harassment (D’Augelli et al. 2002, Kosciw et al. 2014) and the loss of close friends (D’Augelli 2003, Diamond & Lucas 2004); however, studies of adults who disclose their sexual identities to others show positive psychosocial adjustment (Luhtanen 2002, Morris et al. 2001) and greater social support from family members (D’Augelli 2002). In a recent study, Russell et al. (2014) found that despite higher risk for LGBT-based school victimization, those who were out during high school reported lower levels of depression and greater overall well-being in young adulthood (the results did not differ based on gender or ethnicity). Further, those who reported greater concealment of their LGBT identity were still susceptible to victimization but did not show the same benefits in psychosocial adjustment. Such findings demonstrate the positive benefits of coming out in high school despite the risks associated with discriminatory victimization (see sidebar Supporting Youth Through Coming Out).

In summary, there is clear evidence for compromised mental health for LGBT youth, and research in the past decade has identified both risk and protective factors at multiple levels of influence. Important gaps remain, for example, in studies that identify intrapersonal strengths or coping strategies that may enable some LGBT youth to overcome minority stress. Yet this body of research has begun to provide guidance for action at multiple contextual levels.

IMPLICATIONS

Dramatic advances in understanding LGBT youth mental health during the past decade (Saewyc 2011) offer multiple implications for actions. Returning to Figure 2, the contexts that shape the lives of LGBT youth have corresponding implications for supporting mental health at multiple levels, from laws to clinical practice. Existing research shows encouraging findings regarding laws and policies and for education and community programs, yet we are only just beginning to build a research base that provides strong grounding for clinical practice.

Law and Policy

Although only a small number of studies directly address the connection among laws, policies, and mental health, it is widely understood that laws and policies provide the broad, societal-level contexts that shape minority stress and, consequently, mental health. Studies have documented higher psychiatric disorders among LGB adults living in US states that banned marriage for same-sex couples (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2010) and higher psychological distress for LGB adults who lived in states in the months following an election cycle where constitutional amendments to ban marriage for same-sex couples were on the ballot (Rostosky et al. 2009). In recent years, several states have debated or enacted legislation specifically relevant for LGBT youth mental health. At one extreme, the Tennessee legislature failed to pass the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, which would have made it illegal for teachers to discuss homosexuality with students; at the other, the “Mental Health Services for At-Risk Youth” bill in California allows youth ages 12 to 17 to consent to mental health treatment without parental permission and was designed to enable LGBT youth to seek mental health services independent of parental consent. As of this writing, several US states have debated or banned sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts for minors (often called conversion or reparative therapies). These and other legislative efforts likely have mental health implications for LGBT youth, but no studies to date have specifically documented the link between these laws and youth mental health. However, a number of studies have documented the association of local laws and policies with LGBT youth mental health. A study of youth in Oregon showed that multiple indicators of the social environment were linked to lower suicide risk for LGB students, including the proportion of same-sex couples and registered Democrats at the county level (Hatzenbuehler 2011, Hatzenbuehler & Keyes 2013).

School and Community Programs and Practice

Because school attendance is mandatory for youth, and because of consistent evidence of discriminatory bullying and unsafe school climate for LGBT students, education policy is particularly relevant for LGBT mental health. A strong body of research has identified school policies and practices that promote positive school climate and individual student well-being, including feelings of safety, achievement, and positive mental health. Strong evidence indicates that the presence of SOGI-inclusive nondiscrimination and antibullying laws or policies is associated with student safety and adjustment (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes 2013, Russell et al. 2010) and provides a foundation that enables school teachers, administrators, and other personnel to establish an institutional climate that supports the policies and practices noted above (Russell & McGuire 2008). At the level of educational programs and practice, teachers clearly play a key role in establishing a positive school climate for LGBT and all students (Russell et al. 2001), and there is new evidence regarding the benefits of teacher training and classroom curricula that are explicitly inclusive of LGBT people and issues (Snapp et al. 2015a,b) in promoting LGBT student well-being. Finally, at the level of individual student daily experiences and interpersonal interactions, the presence and visibility of information and support on LGBT issues in school, as well as the presence of student-led groups or clubs such as GSAs, are strongly correlated with more affirming interactions with peers, positive school climate, and better student adjustment (Poteat 2012, 2015; Toomey et al. 2011).

This body of evidence regarding school policies represents a major advance in the past decade; much less is known about effective program and practice strategies for community-based organizations (CBOs), even though the number of CBOs that specialize in LGBT youth or offer focused programs for LGBT youth has grown dramatically in the United States and around the world. Clearly, many school-based strategies may be transferable to the CBO context; given the numbers of programs and youth who attend CBOs, an important area for future research will be identifying guiding principles for effective community-based programs for LGBT youth.

Clinical Practice

There is a significant body of clinical writing on LGBT mental health (Pachankis & Goldfried 2004), including guidelines for LGBT-affirmative clinical practice from many professional associations (see Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2012, McNair & Hegarty 2010; see also the Related Resources at the end of this article). These resources typically focus on the general population of LGBT persons and may attend to contexts for which there are LGBT-specific challenges: identity development, couples relationships, parenting, and families of origin (Pachankis & Goldfried 2004). Although most existing guidelines are not specifically designed for youth, the recommendations and discussions of adult LGBT needs are typically relevant for LGBT youth. These guidelines, drawn from the best available descriptive evidence from the research on LGBT mental health, have been important for establishing a professional context that challenges heterosexism and bias in clinical practice (Pachankis & Goldfried 2004).

We review two broad areas of emerging research evidence related to clinical practice. First, promising new research points to specific mental health constructs that appear to be key indicators of compromised mental health for LGBT persons and offer pathways for intervention and treatment. Second, a small number of very new studies document the clinical efficacy of specific treatment strategies to address LGBT mental health (including for youth).

Psychological mechanisms and processes

An emerging body of studies has been designed to investigate constructs related to minority stress and other theoretical models relevant to LGBT youth mental health. Such constructs—rumination, rejection sensitivity, and perceived burdensomeness—have implications for approaches to LGBT-affirmative mental health clinical practice. First, a recent set of studies provides evidence for a causal role of rumination in the association between minority stress and psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2009b): Drawing from two adult samples (average ages in the early twenties), two studies confirmed that LGB participants who reported more stigma-related stressors also experienced more psychological distress, but that the association was strongest for those who reported more rumination following stigma-related stress. These findings highlight the role of emotion regulation in minority stress processes and the potential of clinical approaches that directly address rumination and other maladaptive cognitive responses related to LGBT stigma.

Another recent study tested two key mechanisms from the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness; Joiner et al. 2009) informed by minority stress in a large sample of LGB youth (Baams et al. 2015). Findings showed that the link between minority stress (measured as LGB victimization and stress related to coming out) and mental health (measured as depression and suicide ideation) was mediated by perceived burdensomeness. That is, experiences of minority stress prompted youth to feel that they were a burden to the important people in their lives, and it was these feelings of being a burden that were key correlates of depression and suicide ideation. Further, the association between thwarted belonging and mental health was fully explained by perceived burdensomeness. This latter finding is important because much of the discourse on LGBT mental health has focused on belonging (i.e., social isolation, family rejection, or lack of school belonging), yet results from this study suggest that belonging may not be the critical mechanism. Rather, LGBT-specific approaches to decrease feelings of being a burden to others may be a particularly fruitful area for clinical investigation.

Finally, a recent study conceptualized gay-related rejection sensitivity as an indicator of psychological functioning (Pachankis et al. 2008): In a sample of adult gay men, experiences of parental sexual orientation–related rejection was a strong predictor of gay-related rejection sensitivity, especially among those who reported high levels of internalized homophobia. Results of another study of black, Hispanic, LGB, and female adults’ responses to biased-based discrimination show that those who fail to acknowledge discrimination, or who avoid discussing discriminatory experiences, are more likely to have psychiatric disorders (McLaughlin et al. 2010). Although these studies were conducted with adults (and in one case was limited to gay men), results point to the potential of clinical interventions that focus on analysis of the meanings and experiences associated with stigma-related rejection. Thus, this emerging body of research identifies several psychological mechanisms that may be strategic constructs to address in clinical settings with LGBT youth.

Approaches to treatment

A small number of studies have begun to test treatment approaches that address the specific mental health needs of LGBT populations, including youth. First, although not specific to clinical treatment per se, one study directly asked LGB adolescents with clinically significant depressive and suicidal symptoms to describe the causes of their psychological distress (Diamond et al. 2011). Interviews with 10 youth identified family rejection of sexual orientation, extrafamilial LGB-related victimization, and non-LGB-related negative family life events as the most common causes of psychological distress. Most adolescents in the study also reported social support from at least one family member and from peers or other adults. Several clinically relevant considerations emerged from the interviews, including youths’ wishes that parents were more accepting, and a willingness to participate in family therapy with their parents.

The clinical literature also includes a number of case studies (e.g., Walsh & Hope 2010), as well as investigations of promising approaches for clinical intervention. For example, a study of 77 gay male college students showed that young gay men’s psychosocial functioning (including openness with their sexual orientation) was improved through expressive writing that targeted gay-related stress, especially for those who reported lower social support or who wrote about more severe topics (Pachankis & Goldfried 2010).

A new study by Pachankis and colleagues (2015) reports on the first randomized clinical control trial to assess the efficacy of an adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) approach with young adult gay and bisexual men. The 10-session CBT-based intervention (called Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men, or ESTEEM) focused on stigma-related stressors. Participants reported decreases in depressive symptoms and alcohol use six months after treatment. Notably, the treatment also reduced sensitivity to rejection, internalized homophobia, and rumination, and increased emotional regulation, perceived social support, and assertiveness. The results are exciting and offer the potential for adaptation for women and for LGBT youth.

The research on the critical role of parental rejection and acceptance in LGBT youth mental health (Ryan et al. 2009, 2010) has led to recommendations to educate and engage parents and family in interventions that affirm their LGBT identities (Subst. Abuse Ment. Health Serv. Admin. 2014). Diamond and colleagues (2012) presented preliminary results from the first empirically tested family-based treatment designed specifically for suicidal LGB adolescents. The treatment was based on an adaptation of attachment-based family therapy that included time for parents to process feelings regarding their child’s sexual orientation and raise awareness of their undermining responses to their child’s sexual orientation. Significant decreases in suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms among adolescent participants coupled with high levels of retention demonstrated the success of this approach to treating LGB adolescents and their families.

In summary, few empirical studies have tested clinical approaches to improving the mental health of LGBT youth. However, the small number of existing studies are grounded in the current literature on risk and protective factors as well as psychological mechanisms implicated in minority stress, and they represent an important basis for future clinical research and practice.

CONCLUSIONS AND NEXT STEPS

Much has been learned in the past decade to advance understanding of LGBT youth mental health. Societal changes have led to legal, policy, and structural changes, most of which will ultimately improve the lives and mental health of LGBT youth. But structural change takes time, and in the interim, individual LGBT youth need support and care in order to thrive. There have been important advances in theoretical understandings of LGBT lives, most notably through the framework of minority stress. These advances, and associated empirical research on key mechanisms and processes, point to the relevance of approaches that directly address and interrogate minority stress in the lives of youth and how minority stress processes affect youth well-being. At the same time, given the magnitude of mental health problems experienced by LGBT youth, it is alarming that there are so few empirically supported approaches for working with LGBT youth across a variety of settings, ranging from schools and CBOs to clinical treatment.

There have been extraordinary changes in public understanding and acceptance of LGBT people and issues, and significant advances have been made in scientific understanding of LGBT youth mental health. At the same time, critical gaps in knowledge continue to prevent the most effective policies, programs, and clinical care from addressing mental health for LGBT young people. We have outlined strategies at multiple levels for which there is encouraging evidence and which provide the basis for action. As scholars and clinicians continue work to identify strategies at multiple levels to address LGBT youth mental health—from policy to clinical practice—the existing research already provides a basis for action: Across fields and professions, everyone can be advocates for the legal, policy, program, and clinical changes that promise to improve mental health for LGBT youth.

CHANGES IN GENDER IDENTITY DIAGNOSES IN THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS.

The psychiatric categorization of gender-variant behavior and identity has evolved since the introduction of gender identity disorder (GID) of children (GIDC) and transsexualism in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) (Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1980). The DSM-IV (Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1994) eliminated the nontranssexual type subcategory of GID [added to the DSM-III-R (Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1987)] and combined diagnoses of GIDC and transsexualism into GID. Because of critiques regarding the limitations and stigmatization of GID (see Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin 2010), the DSM-5 (Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2013) introduced gender dysphoria in its place (with separate criteria for children and adolescents/adults).

Among other improvements, the adoption of gender dysphoria reflected (a) a shift away from inherently pathologizing the incongruence between one’s natal sex and gender identity toward a focus on the distress associated with this discordance, and (b) recognition of a gender spectrum with many gender identities and expressions (see Zucker 2014). Despite advances, many argue that diagnoses unduly label and pathologize legitimate and natural gender expressions (Drescher 2014). Others voice concerns that the loss of a gender identity diagnosis altogether might restrict or eliminate insurance coverage of affirming medical services, including body modification and hormone treatment.

SUPPORTING YOUTH THROUGH COMING OUT.

Coming out is associated with positive adjustment for adults, yet for youth, coming out is often a risk factor for discrimination and victimization. Can coming out be healthy, despite the risks?

It is developmentally normal for youth to develop an understanding of sexual orientation and identity. Today’s youth come out at younger ages than ever before. Prior cohorts came out as adults and young adults, often after they were financially and legally independent, and at a different stage of life experience and maturity.

When a young person is ready to come out, many adults may think, “Can’t you wait… ?” Yet they never ask a heterosexual youth to wait to be straight. Adults worry for the well-being and safety of youths who come out.

The role of adults is to support youth to think carefully about how they come out. Rather than come out through social media or to many people at once, youth should be encouraged to identify one or two supportive friends, adults, or family members to whom they can come out. Beginning with people they trust, they can build a network of support, which can be leveraged if they experience rejection as they come out to others.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Contemporary youth come out as LGBT at younger ages than in prior cohorts of youth.

Younger ages of coming out intersect with a developmental period characterized by concerns with self-consciousness, conformity, and peer regulation.

Coming out is typically stressful for LGBT youth but is also associated with positive mental health, especially over the long run.

LGBT mental health must be understood in the context of other salient personal identities: gender, ethnic, cultural, and religious.

Significant advances in knowledge of policies and practices have created supportive school environments and contributed to positive mental health for LGBT youth.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Significant gaps remain in knowledge of clinically proven models for reducing mental health problems and promoting mental health in LGBT youth.

Serious gaps remain in knowledge regarding mental health for transgender youth.

Strong evidence indicates that bisexual youth have higher rates of compromised mental health, and more research and theory are needed to understand these patterns.

Intersectional approaches are needed to better understand the interplay of sexual orientation and gender identity with race and ethnicity, social class, gender, and culture.

Glossary

- LGBT

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender; some scholars include Q to refer to queer or questioning

- Mental health

broadly defined to include mental health indicators (i.e., depression, anxiety, suicidality) and behavioral health correlates (i.e., substance use)

- Gender identity

one’s sense and subjective experience of gender (maleness/femaleness), which may or may not be consistent with birth sex

- Sexual orientation

enduring sense of emotional, sexual attraction to others based on their sex/gender

- SOGI

sexual orientation and gender identity

- GSA

Gay-Straight Alliance school club

- Sexual identity

self-label to describe one’s sexual orientation, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or straight

- CBO

community-based organization

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc.; Washington, DC: 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed Am. Psychiatr. Publ.; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed., rev. Am. Psychiatr. Publ.; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed Am. Psychiatr. Publ.; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Am. Psychiatr. Publ.; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychol. Assoc. Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients. Am. Psychol. 2012;67:10–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Bos HM, Jonas KJ. How a romantic relationship can protect same-sex attracted youth and young adults from the impact of expected rejection. J. Adolesc. 2014;37:1293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Dev. Psychol. 2015;51:688–96. doi: 10.1037/a0038994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Sandfort TG, Eisenberg A, Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:1148–63. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Koenig B, Espelage DL. LGB and questioning students in schools: the moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009;38:989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black WW, Fedewa AL, Gonzalez KA. Effects of “safe school” programs and policies on the social climate for sexual-minority youth: a review of the literature. J. LGBT Youth. 2012;9:321–39. [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick M. Adolescent suicide attempts: risks and protectors. Pediatrics. 2001;107:485–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:468–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: a decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011;21:166–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Alcohol and tobacco use patterns among heterosexually and homosexually experienced California women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MN, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Mental health disorders in young urban sexual minority men. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;56:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Cent. Dis. Control Prev.) 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, United States—2013. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2012. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Alegria M, Ortega AN, Takeuchi D. Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75:785–94. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003;71:53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Kettenis PT, Pfäfflin F. The DSM diagnostic criteria for gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010;39:499–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9562-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009;60:631–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolacion TB, Russell ST, Sue S. Sex, race/ethnicity, and romantic attractions: multiple minority status adolescents and mental health. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2004;10:200–14. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:433–56. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Lesbian and bisexual female youths aged 14 to 21: developmental challenges and victimization experiences. J. Lesbian Stud. 2003;7:9–29. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Factors associated with parents’ knowledge of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths’ sexual orientation. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2010;6:178–98. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:361–71. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, Hershberger SL. Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2002;17:148–67. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GM, Diamond GS, Levy S, Closs C, Ladipo T, Siqueland L. Attachment-based family therapy for suicidal lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: a treatment development study and open trial with preliminary findings. Psychotherapy. 2012;49:62–71. doi: 10.1037/a0026247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GM, Shilo G, Jurgensen E, D’Augelli A, Samarova V, White K. How depressed and suicidal sexual minority adolescents understand the causes of their distress. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health. 2011;15:130–51. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. New paradigms for research on heterosexual and sexual-minority development. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. 2003;32:490–98. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Lucas S. Sexual-minority and heterosexual youths’ peer relationships: experiences, expectations, and implications for well-being. J. Res. Adolesc. 2004;14:313–40. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM, Bein E, Ayala G. Homophobia, poverty, and racism: triple oppression and mental health outcomes in Latino gay men. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual Orientation and Mental Health: Examining Identity Development in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual People. Contemporary Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Psychology. Am. Psychol. Assoc.; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 207–24. [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BLB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:1134–47. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher J. Gender identity diagnoses: history and controversies. In: Baudewijntje PCK, Steensma PD, de Vries ALC, editors. Gender Dysphoria and Disorders of Sex Development: Progress in Care and Knowledge. Springer; New York: 2014. pp. 137–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DT, Hatzenbuehler ML. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:272–78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, Gates GJ. Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Service Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth who are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless. Williams Inst. True Colors Fund, Palette Fund; Los Angeles, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eskin M, Kaynak-Demir H, Demir S. Same-sex sexual orientation, childhood sexual abuse, and suicidal behavior in university students in Turkey. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2005;34:185–95. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-1796-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood J, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56:876–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Sexual orientation and mental health in a birth cohort of young adults. Psychol. Med. 2005;35:971–81. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Pasley K. Sexual (minority) trajectories, mental health, and alcohol use: a longitudinal study of youth as they transition to adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:1508–27. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TM, Merry SN, Robinson EM, Denny SJ, Watson PD. Self-reported suicide attempts and associated risk and protective factors among secondary school students in New Zealand. Aust. N Z J. Psychiatry. 2007;41:213–21. doi: 10.1080/00048670601050481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Bakeman R. Coming-out across the life course: implications of age and historical context. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2006;35:287–96. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CS, Beach FA. Patterns of Sexual Behavior. Harper; New York: 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM. Similarities and differences in the pursuit of intimacy among sexual minority and heterosexual individuals: a personal projects analysis. J. Soc. Issues. 2011;67:282–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup . Gay and Lesbian Rights. Gallup; 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Wissow LS, Woods ER, Goodman E. Sexual orientation and risk of suicide attempts among a representative sample of youth. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1999;153:487–93. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Youth Suicide. Vol. 3. Alcohol, Drug Abuse, Mental Health Admin., US Dep. Health Human Serv.; Washington, DC: 1989. Gay male and lesbian youth suicide; pp. 115–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Hughes M, Ostrow D, Kessler RC. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91:933–39. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN (Gay Lesbian Straight Educ. Netw.) Teaching Respect: LGBT-Inclusive Curriculum and School Climate (Research Brief) GLSEN; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN (Gay Lesbian Straight Educ. Netw.) State Maps. GLSEN; New York: 2015. http://www.glsen.org/article/state-maps. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Szalacha L, Westheimer K. School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 2006;43:573–89. [Google Scholar]

- Greytak EA, Kosciw JG. Predictors of US teachers’ intervention in anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender bullying and harassment. Teach. Educ. 2014;25:410–26. [Google Scholar]

- Greytak EA, Kosciw JG, Boesen MJ. Educating the educator: creating supportive school personnel through professional development. J. Sch. Violence. 2013;12:80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol. Bull. 2009;135:707–30. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Birkett M, Van Wagenen A, Meyer IH. Protective school climates and reduced risk for suicide ideation in sexual minority youths. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:279–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: results from a prospective study. Dev. Psychol. 2008a;44:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013;53:S21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am. J. Public Health. 2009a;99:2275–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:452–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008b;49:1270–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol. Sci. 2009b;20:1282–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, Boxer A. Children of Horizons. Beacon; Boston: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker E. The adjustment of the male overt homosexual. J. Proj. Tech. 1957;21:18–31. doi: 10.1080/08853126.1957.10380742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS. Heterosexual adolescents’ and young adults’ beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality and gay and lesbian peers. Cogn. Dev. 2006;21:420–40. [Google Scholar]

- Inst. Med. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. Natl. Acad. Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Influential and authoritative report on LGBT health.

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2009;118:634–46. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, Stirratt MJ. Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: the effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:500–10. doi: 10.1037/a0016848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustin TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–64. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Georgiades K, Green JG, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication adolescent supplement. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69:372–80. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Indiana Univ. Press; Bloomington: 1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE, Gebhard PH. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Indiana Univ. Press; Bloomington: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. GLSEN; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Palmer NA, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. GLSEN; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, Coleman BR, Mustanski BS. Coping with LGBT and racial-ethnic-related stressors: a mixed-methods study of LGBT youth of color. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014;24:703–19. [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen RK. Identity, stigma management, and well-being. J. Lesbian Stud. 2002;7:85–100. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. J. Adolesc. Health. 2011;49:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. Comprehensive meta-analysis of studies of depression and suicidality among sexual minority youth.

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analyses and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald GJ. Individual differences in the coming out process for gay men: implications for theoretical minds. J. Homosex. 1982;8:47–60. doi: 10.1300/J082v08n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:1477–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair RP, Hegarty K. Guidelines for the primary care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people: a systematic review. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010;8:533–41. doi: 10.1370/afm.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995;36:38–56. Articulation of the influential theory for research related to LGBT youth mental health.

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003;129:674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social status confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;67:368–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Waldo CR, Rothblum ED. A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:61–71. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL, Killen M. Challenging gender stereotypes: resistance and exclusion. Child Dev. 2015;86:681–94. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Hatzenbuehler ML, Newcomb ME. Envisioning an America without sexual orientation inequities in adolescent health. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:218–25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:2426–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL. Sexual attraction and trajectories of mental health and substance use during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:179–90. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9729-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D. The development of prejudice in children. In: Augoustino M, Reynolds KJ, editors. Understanding Prejudice, Racism, and Social Conflict. Sage; London: 2001. pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–10. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Clinical issues in working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2004;41:227–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Expressive writing for gay-related stress: psychosocial benefits and mechanisms underlying improvement. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010;78:98–110. doi: 10.1037/a0017580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR, Ramrattan ME. Extension of the rejection sensitivity construct to the interpersonal functioning of gay men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008;76:306–17. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]