Abstract

Introduction

Tremor is thought to be a rare feature of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the database of the CurePSP brain bank at Mayo Clinic Florida to retrieve all available clinical information for PSP patients. All patients underwent a standard neuropathological assessment and an immunohistochemical evaluation for tau and α-synuclein. DNA was genotyped for the MAPT H1/H2 haplotype.

Results

Of the 375 PSP patients identified, 344 had a documented presence or absence of tremor, which included 146 (42%) with tremor, including 29 (20%) with postural/action tremors, 16 (11%) with resting tremor, 7 (5%) with intention tremor, 20 (14%) with a combination of different types of tremor, and 74 (51%) patients who had tremor at some point during their illness, but details were unavailable. The tremor severity of 96% of the patients (54/55) who had this data was minimal to mild. The probability of observing a tremor during a neurological examination during the patient’s illness was estimated to be ~22%. PSP patients with postural/action tremors and PSP patients with resting tremor responded to carbidopa-levodopa therapy more frequently than PSP patients without tremor, although the therapy response was always transient. There were no significant differences in pathological findings between the tremor groups.

Conclusions

Tremor is an inconspicuous feature of PSP; however, 42% (146/344) of the PSP patients in our study presented some form of tremor. Because there is no curative therapy for PSP, carbidopa/levodopa therapy should be tried for patients with postural, action, and resting tremor.

Keywords: progressive supranuclear palsy, tremor, carbidopa/levodopa therapy, neuropathology, MAPT H1/H2 haplotype

INTRODUCTION

Tremor is the most common movement disorder. Clinically, tremor can be classified into four major types; postural, action, resting, and intention tremor [1]. Postural and action tremors comprise the largest group of tremor and can be seen in many conditions, including essential tremor (ET). Resting tremor is a less common type of tremor, but resting tremor or combination of resting tremor and postural/action tremors are generally seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease and other parkinsonian disorders [2]. Tremor is not considered to be a common feature of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). PSP is a neurodegenerative disorder [3] and is clinically characterized by early falls, supranuclear vertical gaze palsy, parkinsonism, and dystonia [4]. Pathologically, PSP is characterized by the accumulation of microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT)-positive neurofibrillary tangles in the basal ganglia, diencephalon, and brainstem. Louis et al. reported that 11 (12%) of their cohort of 83 autopsied ET patients had pathological findings that were consistant with those of PSP [5]. Additionally, the MAPT H1 haplotype, which was originally associated with PSP, has been shown to be a risk factor for ET [6, 7], suggesting a possible pathological link between these two entities. We are influenced by Louis’ work and other previous works that found a common underlying genetic factor between PSP and ET. We looked through our brain bank data and found PSP patients with tremor more frequently than we expected. This study focuses on the characteristics of tremor seen in autopsy-confirmed PSP cases and compares other clinical and pathological characteristics between PSP with and without tremor.

METHODS

Subjects

We retrieved data describing PSP patients from the Mayo Clinic Florida brain bank for neurodegenerative disorders. We reviewed the medical records of patients pathologically diagnosed as having PSP (n=375) between 1998 and 2008. Medical records were obtained from the institutions that sent us brain tissue. Demographics and clinical features including tremor, parkinsonism, falls, vertical gaze palsy, dementia, frontal lobe dysfunction, pyramidal signs, dystonia, myoclonus, sleep disorders, urinary incontinence, and visual hallucinations were abstracted. We ascertained tremor characteristics and responsiveness to carbidopa/levodopa therapy from the available medical records. We also reviewed the documentation regarding the patient’s initial prominent clinical phenotype, degree of responsiveness to carbidopa/levodopa therapy, and asymmetry of clinical phenotype. The Mayo Clinic/CurePSP brain bank’s standard questionnaire was administered to the next of kin or caregiver after the brain was received. We asked caregivers whether patients had tremor during the patient’s lifetime. We also reviewed whether there was any history of neurological disorders in the patient’s family. The neurological disorders that were seen in the relatives of the patients included PSP, Parkinson’s disease, parkinsonism, motor neuron disease, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and tremor. The patients were classified into four groups: PSP without tremor, PSP with postural or action tremor, PSP with resting tremor, and PSP with intention tremor.

Pathological analysis

All patients underwent a standardized neuropathological assessment as a part of the standard procedures of the CurePSP brain bank. This assessment included immunohistochemical localization of phospho-tau (CP13, mouse monoclonal IgG1, 1:1000) in multiple brain regions [4]. Sections for the amygdala were also processed for immunohistochemical staining with α-synuclein (NACP, rabbit polyclonal; 1:3,000) to screen for the presence of α-synuclein pathology. All immunohistochemical analyses were performed using a DAKO-Autostainer (DAKO-Cytomaton, Carpinteria, CA, USA). The neuropathological diagnosis of PSP was based upon published criteria [8].

Genetic screening

For each case, DNA was extracted from frozen brain tissue and genotyped for the MAPT H1/H2 haplotype using TaqMan assays for the rs1052553 polymorphism (NG_007398.1 107103 A>G) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). TaqMan reactions were analyzed on the ABI 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The rate of genotype calls was ≥98% in the study population.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SigmaPlot version 11.0. The mean differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. The chi-square test was used to compare the frequencies between the different groups. We used ANOVA on ranks for semi-quantitative pathological data. We analyzed the distribution of MAPT H1/H2 haplotype on R software (http://www.R-project.org.) by fitting a logistic regression model to the clinical phenotype. For this analysis, we assumed an additive genetic model, and age-at-death, age-at-onset, and sex were included as covariates.

This study was approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board, and all post-mortem samples were acquired by informed consent from the next-of-kin.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

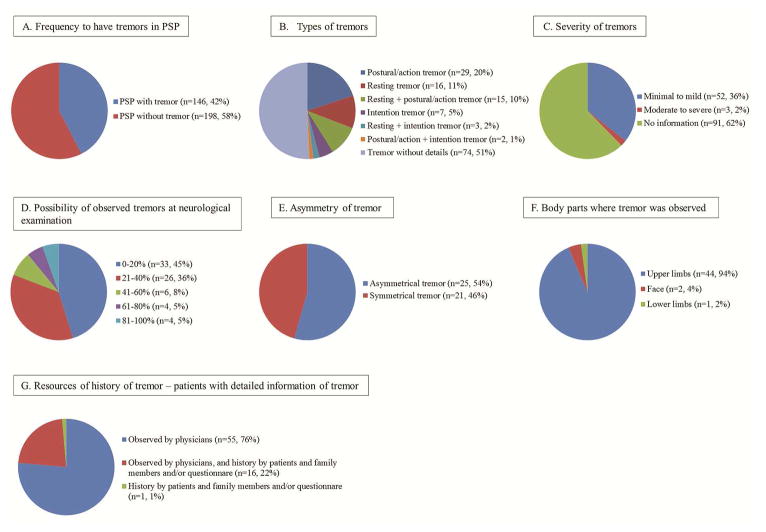

Of the 375 PSP patients, 344 were had a documented presence or absence of tremor. Approximately 42% of the patients (146/344) experienced tremor during the course of their illnesses (Figure 1A). Among the patients with tremor, postural or action tremor (n=29, 20%) was the most common, followed by resting tremor (n=16, 11%), resting and postural or action tremor (n=15, 10%), intention tremor (n=7, 5%), resting and intention tremor (n=3, 2%), and postural or action tremor and intention tremors (n=2, 1%). The details of tremor characteristics were unavailable for 74 patients reported to have tremor (51%) (Figure 1B). Table 1 shows comparison of demographics, as well as clinical, pathological, and genetic features of cases of PSP with and without tremor. In the table, we excluded patients who had combination of more than two kinds of tremor and patients who had tremor but no details about the type of tremor so we could compare the characteristics of patients who presented with a single kind of tremor. The severity of tremor was mentioned in the medical records of 55 patients, and most of them (95%) had minimal to mild tremor (Figure 1C). Tremor was observed by physicians during the examinations of 149 patients. We calculated the probability of observing tremor by utilizing the following methods: the number of times tremor seen by physicians was divided by the number of times the patient saw the physician. The probabilities of observing a tremor during the examination of a PSP patient were as follows: 0–20% (45%), 21–40% (36%), 41–60% (8%), 61–80% (5%), and 81–100% (5%) (Figure 1D). In approximately half of the patients who had tremor, the tremor was asymmetrical (Figure 1E). Tremor was observed mostly in the upper limbs (n=44, 94%), which was followed by the face (n=2, 4%) and lower limbs (n=1, 2%) (Figure 1F). The majority of patients who experienced tremor in the presence of a physician also had more detailed information about their tremor in the medical record (Figure 1G). PSP with tremor responded to carbidopa/levodopa therapy more frequently than PSP without tremor, although the responsiveness to the therapy was transient for all of the patients (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1. A) Frequency of Tremor.

One hundred forty-nine of the 344 cases (42%) who had a documented presence or absence of tremor had reported having tremor at some point during the course of their illnesses. 1B) Types of Tremor: Postural/action tremor (n=29, 20%) were the most common form of tremor, which was followed by resting tremor (n=16, 11%), intention tremor (n=7, 5%), and a combination of different kinds of tremor (n=20, 13%). However, the details about the types of tremor were not available for the remaining 74 patients (51%). 1C) Severity of Tremor: Among the patients whose information about tremor severity was available (n=55), 52 (95%) had minimal to mild degree of tremor, and three (2%) had a moderate to marked degree of tremor. 1D) Probability of observing tremor: The probability of a physician observing tremor in patients who had the evaluated presence of tremor at least twice during the course of their illness or in those who received a comprehensive neurological examination that included an evaluation of the cranial nerves and an assessment of coordination and reflexes, including motor, sensory, and deep tendon reflexes are as follows: 0–20% for 33 patients (45%), 21–40% for 26 patients (36%), 41–60% 6 patients (8%), 61–80% for 4 patients (5%), and 81–100% for 4 patients (5%) (median 22% [7–33%]). 1E) Asymmetry of tremor: Among the 46 patients whose information about asymmetrical tremor was available, 25 patients were reported to have asymmetry. 1F) Locations of observed tremor: Among the patients (n=47) who had descriptions of tremor locations, 44 patients (94%) had tremor in their upper limbs, 2 patients (4%) had facial tremor, and 1 patient (2%) had tremor in the lower limbs. 1G) Resources of history of tremor: For patients with detailed tremor information, tremor was most frequently confirmed by physicians (n=55, 76%), followed by confirmation by both physicians and by medical histories provided by patients, family members, and questionnaires (n=16, 22%), and finally by confirmation only from the medical histories provided by patients, family members, and questionnaires (n=1, 1%).

Table 1.

Comparison of the demographics, clinical, pathological, and genetic features between PSP cases without and with tremor

| PSP without tremor | PSP with postural and/or action tremors | PSP with resting tremor* | PSP with intention tremor | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient number | 198 | 29 | 16 | 7 | - |

| Demographics | |||||

| Mean AAO of PSP (years) | 67 | 67 | 70 | 62 | 0.10 |

| Mean DD of PSP (years) | 7.5 | 7 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 0.85 |

| Female | 101 (51%) | 14 (48%) | 3 (19%) | 2 (29%) | 0.06 |

| Family history of neurological diseases | 33/198 (17%) | 5/29 (17%) | 6/16 (38%) | 1/7 (14%) | 0.21 |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Parkinsonism | 195/195 (100%) | 29/29 (100%) | 16/16 (100%) | 7/7 (100%) | - |

| Falls | 194/195 (99%) | 28/28 (100%) | 16/16 (100%) | 7/7 (100%) | 0.97 |

| Vertical gaze palsy | 121/121 (100%) | 27/27 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 5/5 (100%) | - |

| Dementia/amnestic syndrome | 110/130 (85%) | 21/24 (88%) | 11/14 (79%) | 5/6 (83%) | 0.91 |

| Frontal lobe dysfunction | 41/42 (98%) | 6/7 (86%) | 4/5 (80%) | 1/2 (50%) | 0.03 |

| Pyramidal signs | 66/76 (87%) | 12/12 (100%) | 10/12 (83%) | 4/6 (67%) | 0.25 |

| Dystonia | 43/55 (78%) | 3/14 (21%) | 6/8 (75%) | 1/1 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Myoclonus | 3/26 (12%) | 2/7 (29%) | 1/2 (50%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0.39 |

| Sleep disorders | 105/150 (70%) | 13/20 (65%) | 8/11 (73%) | 2/5 (40%) | 0.52 |

| Urinary incontinence | 54/90 (60%) | 10/18 (56%) | 8/10 (80%) | 4/6 (67%) | 0.60 |

| Visual hallucination | 22/126 (17%) | 4/18 (22%) | 3/10 (30%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0.52 |

| Responsiveness to levodopa-carbidopa therapy (none to minimal responder/mild to good responder) | 33/1 | 15/0 | 6/2 | 2/1 | 0.02 |

| Initial prominent phenotype (RS/CBS/FTD/PSP-P) (%) | 88/5/4/2/1 (total n=118) | 85/4/4/7/0 (total n=26) | 63/0/6/31/0 (total n=16) | 58/14/14/14/0 (total n=7) | - |

| Pathological findings | |||||

| Mean brain weight (grams) | 1168 | 1133 | 1245 | 1244 | 0.07 |

| Mean Braak NFT stage | II | II–III | II | II | 0.06 |

| Presence of LB pathology | 9/198 (5%) | 4/29 (14%) | 2/16 (13%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0.14 |

| Presence of vascular pathology | 30/197 (15%) | 2/29 (7%) | 2/16 (13%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0.45 |

| Genetic findings | |||||

| MAPT (n) | 197 | 29 | 16 | 7 | - |

| H1H1: H1H2: H2H2 (%) | 86.8: 11.7: 1.5 | 82.1: 17.9: 0 | 93.8: 6.3: 0 | 85.7: 14.3: 0 | - |

| H1: H2 (%) | 92.6: 7.4 | 91.1: 8.9 | 96.9: 3.1 | 92.9: 7.1 | - |

| OR (95% CI) | 2.94 (0.42–20.58) | 0.28 (0.03–2.73) | 1.23 (0.09–16.27) | - | |

| p-value | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.88 | - | |

AAO=age at onset; DD=disease duration; LB=Lewy body; NFT=neurofibrillary tangles; PSP=progressive supranuclear compared with PSP without tremor group; ‡=significant difference were observed compared with PSP without tremor postural, action, and intention tremors

Pathological findings

There were no significant differences in the severity of the semi-quantitative scores for tau pathology or the frequency of the other pathologies after adjusting for multiple comparisons between the groups (Supplemental Table 2).

Genetic findings

The presence of tremor in PSP patients was not associated with significant differences in the frequency of MAPT H1/H2 haplotypes (OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.38–1.95; p-value 0.71). Although a notably higher MAPT H1 frequency was observed in the cases with resting tremor and PSP (97%), but this elevated haplotype frequency did not significantly affect the OR value (Table 1).

Table 1 summarizes the demographic, clinical, pathological, and genetic features of the cases.

DISCUSSION

Tremor is thought to be a relatively rare feature of PSP. Litvan et al. reported that approximately 20% of 163 autopsy-confirmed PSP cases collected from five independent institutions had tremor, although details of the tremor were not available [9]. In the present study, 42% of PSP patients were found to have tremor. A possible reason for the discrepancy between these results and ours is that we not only abstracted the information from collected clinilcal charts, but we also utilized a questionaire to ask for the presence of tremor in caregivers. The tremor seen in our cohort was characterized by intermittent and minimal-mild tremor. Postural/action tremor was the most common form of tremor followed by resting tremor and intention tremor. The retrospective nature of the data collection in our methods could potentially be another cause of discrepancy.

Louis et al.[5] reported that 11 cases of their cohort of autopsied 89 ET cases (12%) had pathological findings consistent with PSP. Among these cases, nine developed ET prior to the onset of parkinsonism. In our cohort, one case (3%) from the postural/action tremor group was reported to have experienced tremor prior to the onset of PSP. This patient developed a slight action tremor of the left upper limb at age 60 years followed by Richardson syndrome at age 76 years. The frequency of tremor in our series (42%) is much higher than that reported by Louis et al (12%) [5]. As the CurePSP brain bank at the Mayo Clinic in Florida, we have widely accepted brain donation from patients who had PSP and related disorders, including corticobasal degeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body disease, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration from all over the country. However, Louis’ research team solicits donations from patients with tremolous disorders. We have retrospectively but systematically collected clinical information from patients with PSP from clinical notes and a formal questionnaire administered to the next of kin or caregiver, which could explain the discrepancy.

So far, several pathological characteristics have been reported in ET cases; these include a reduction in the number of Purkinje cells and an increased number of torpedoes in the cerebellum [10], but no specific structural abnormality has been identified to date. In this study, the presence of tremor did not correlate with the distribution or severity of neuronal and glial tau pathology in the cerebellum and locus ceruleus; therefore, it is doubtful whether neuronal and glial tau pathology are involved in the generation of ET.

As a limitation of our study, we researched our cohort medical records in a retrospective fashion, thus no direct or prospective clinical assessment was performed. Retrospective data collection may result in the exclusion of some clinical information and the inclusion of tremor cases with other involuntary movements, including dystonia, orthostatic tremor, and medication effects, which may decrease the power to classify our PSP patients into specific tremor groups. This limitation may explain the failure to find significant differences in some of our assesments, i.e. the increased frequency of H1 haplotype in the resting tremor group. It has been previously shown that the MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with an increased risk for PSP [11] and ET [7] patients. Our study supports that the presence of tremor is not influenced by H1 haplotype in PSP; however, it remains unclear whether the frequency of H1 haplotype has an effect on the specific tremor presentations in PSP. The second limitation is that the amount of carbidopa/levodopa varied from patient to patient. Some patients did not receive an adequate dose of carbidopa/levodopa. The third limitation is that ET is very common in this age group, and some of the postural-action tremor could simply be coincidental. Furthermore, distinguishing different types of tremor is not always straightforward; thererfore, even expert phisicians could differ in how they assign these labels. Additionally, individuals can present with tremor when tired or stressed.

In summary, we found that tremor is a relatively common feature of autopsy-proven PSP and that the associated tremor is intermittent or could be too subtle to be noticed on clinical examination. Physicians should try carbidopa-levodopa therapy for the PSP patients with postural/action and resting tremor, particularly during the initial stages of their illness because the treatment could ameliorate their symptoms. Additional investigation through longitudinal prospective studies to provide further detailed characterization of tremor in PSP is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We reviewed medical records of 375 autopsied progressive supranuclear palsy patients.

One hundred forty-six patients (42%) were noted to experience tremor.

Tremors seen in the patients included postural/action, resting, and intention tremors.

Tremor severity is usually mild, and the chance of observing a tremor is low.

We suggest tremor is a relatively common feature of progressive supranuclear palsy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelly E. Viola, ELS, for her editorial support.

Footnotes

Author Contribution

Shinsuke Fujioka: Execution of the statistical analysis; execution of the project; writing of the first draft.

Avi Algom: Execution of the project; review and critique of the manuscript.

Melissa E. Murray: Execution of the project; review and critique of the manuscript.

Monica Y. Sanchez-Contreras: Revising the manuscript; analysis and interpretation of data.

Pawel Tacik: Review and critique of the manuscript.

Yoshio Tsuboi: Execution of the statistical analysis; review and critique of the manuscript.

Jay A. Van Gerpen: Review and critique of the manuscript.

Ryan J. Uitti: Review and critique of the manuscript.

Rosa Rademakers: analysis and interpretation of data; revising the manuscript.

Owen A. Ross: Execution of the project; review and critique of the manuscript.

Zbigniew K. Wszolek: Review and critique of the manuscript.

Dennis W Dickson: Conceptualization, organization of the research project; review and critique of the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure/Conflict of Interest:

Shinsuke Fujioka: Dr. Fujioka receives supports from the gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch.

Avi Algom: Dr. Algom reports no disclosures.

Melissa E. Murray: Dr. Murray is partially supported by NIH/P50NS072187

Monica Y. Sanchez-Contreras: Dr. Sanchez-Contreras reports no disclosures

Pawel Tacik: Dr. Tacik is supported by the Max Kade Foundation, the Allergan Medical Educational Grant and the Jaye F. and Betty F. Dyer Foundation Fellowship

Yoshio Tsuboi: Dr. Tsuboi receives reports no disclosures.

Jay A. Van Gerpen: Dr. van Gerpen is partially supported by NIH/NINDS P50NS072187

Ryan Uitti: Dr. Uitti is partially supported by NIH/NINDS P50NS072187

Rosa Rademakers: Dr. Rademakers is partially supported by NIH P50NS072187.

Owen Ross: Dr. Ross is partially supported by the NIH/NINDS P50 NS072187, R01 NS078086, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Zbigniew Wszolek: Dr. Wszolek is partially supported by the NIH/NINDSP50 NS072187, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, NIH U01763910, and The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust, and Cecilia and Dan Carmichael Family Foundation.

Dennis Dickson: Dr. Dickson receives funding from NIH/NINDSP50 NS072187

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shinsuke Fujioka, Email: shinsuke@cis.fukuoka-u.ac.jp.

Avi A. Algom, Email: aaalgom@yahoo.com.

Melissa E. Murray, Email: murray.melissa@mayo.edu.

Monica Y. Sanchez-Contreras, Email: sanchezcontreras.monica@mayo.edu.

Pawel Tacik, Email: Tacik.Pawel@mayo.edu.

Yoshio Tsuboi, Email: tsuboi@cis.fukuoka-u.ac.jp.

Jay A. Van Gerpen, Email: vangerpen.jay@mayo.edu.

Ryan J. Uitti, Email: uitti.ryan.mayo.edu.

Rosa Rademakers, Email: Rademakers.rosa@mayo.edu.

Owen A. Ross, Email: ross.owen@mayo.edu.

Zbigniew K. Wszolek, Email: wszolek.zbigniew@mayo.edu.

Dennis W. Dickson, Email: dickson.dennis@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Puschmann A, Wszolek ZK. Diagnosis and treatment of common forms of tremor. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:65–77. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deuschl G, Papengut F, Hellriegel H. The phenomenology of parkinsonian tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(Suppl 1):S87–89. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeve BF. Progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(Suppl 1):S192–194. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujioka S, Algom AA, Murray ME, Strongosky A, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Rademakers R, Ross OA, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW. Similarities between familial and sporadic autopsy-proven progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 2013;80:2076–2078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b2eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis ED, Babij R, Ma K, Cortes E, Vonsattel JP. Essential tremor followed by progressive supranuclear palsy: postmortem reports of 11 patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:8–17. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31827ae56e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittman AM, Myers AJ, Duckworth J, Bryden L, Hanson M, Abou-Sleiman P, Wood NW, Hardy J, Lees A, de Silva R. The structure of the tau haplotype in controls and in progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1267–1274. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilarino-Guell C, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Rajput A, Mash DC, Papapetropoulos S, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Uitti RJ, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW, Farrer MJ, Ross OA. MAPT H1 haplotype is a risk factor for essential tremor and multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2011;76:670–672. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c30c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauw JJ, Daniel SE, Dickson D, Horoupian DS, Jellinger K, Lantos PL, McKee A, Tabaton M, Litvan I. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy) Neurology. 1994;44:2015–2019. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, Goetz CG, Golbe LI, Grafman J, Growdon JH, Hallett M, Jankovic J, Quinn NP, Tolosa E, Zee DS. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, Honig LS, Rajput A, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Ross WG, Elble RJ, Erickson-Davis C, Moskowitz CB, Lawton A. Torpedoes in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, essential tremor, and control brains. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1600–1605. doi: 10.1002/mds.22567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rademakers R, Melquist S, Cruts M, Theuns J, Del-Favero J, Poorkaj P, Baker M, Sleegers K, Crook R, De Pooter T, Bel Kacem S, Adamson J, Van den Bossche D, Van den Broeck M, Gass J, Corsmit E, De Rijk P, Thomas N, Engelborghs S, Heckman M, Litvan I, Crook J, De Deyn PP, Dickson D, Schellenberg GD, Van Broeckhoven C, Hutton ML. High-density SNP haplotyping suggests altered regulation of tau gene expression in progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3281–3292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.