Abstract

Are DNA damage and mutations possible causes or consequences of aging? This question has been hotly debated by biogerontologists for decades. The importance of DNA damage as a possible driver of the aging process went from being widely recognized to then forgotten, and is now slowly making a comeback. DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) are particularly relevant to aging because of their toxicity, increased frequency with age and the association of defects in their repair with premature aging. Recent studies expand the potential impact of DNA damage and mutations on aging by linking DNA DSB repair and age-related chromatin changes. There is overwhelming evidence that increased DNA damage and mutations accelerate aging. However, an ultimate proof of causality would be to show that enhanced genome and epigenome stability delays aging. This is not an easy task, as improving such complex biological processes is infinitely more difficult than disabling it. We will discuss the possibility that animal models with enhanced DNA repair and epigenome maintenance will be generated in the near future.

Keywords: Aging, DNA double strand break repair, epigenome, genomic instability, heterochromatin, longevity

DNA damage and mutations accumulate during aging

DNA is distinct from all other cellular macromolecules in that it cannot be easily discarded and replaced. A cell with damaged DNA attempts to repair the damage, which is executed successfully most of the time. If the damage is too severe the cell will either become senescent or undergo cell death. The DNA repair machinery is highly efficient and in most cases the original DNA sequence is faithfully restored. However, occasionally repair is erroneous, leading to point mutations, small and large insertions or deletions, and large scale rearrangements. The nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway of DSB repair is particularly error prone, almost always resulting in a deletion or insertion. Once a mutation is introduced into the DNA it will remain there until the death of the cell. Over the lifetime of an organism somatic mutations accumulate leading to dysregulation of transcription patterns, tissue dysfunction, and possibly cancer.

DNA DSBs cause premature aging and senescence

Treatments that result in induction of DNA DSBs, such as gamma-irradiation and certain types of chemotherapy, lead to cellular senescence and accelerated aging in animal models and in human cancer survivors [1]. However, radiation also damages other cellular macromolecules, making it difficult to unequivocally link DSB induction to premature aging. Recently a mouse model was reported where DSBs were induced by controlled expression of a restriction enzyme [2]. These mice displayed multiple signs of aging indicating that DSBs alone can trigger aging pathology.

DNA DSB repair declines with age

Several classical studies revealed that mutations do not simply accumulate over time, but the rate of mutation accumulation increases with age [3–7]. Furthermore, aged tissues accumulated a unique type of mutation – genomic rearrangements, not seen in young tissues [3, 8–12]. Genomic rearrangements, resulting from errors of DSB repair, affect multiple genes and have much broader consequences than point mutations. These findings suggest that multiple DNA repair pathways, and particularly DSB repair, become less efficient and more error-prone with age.

Several studies showed reduced levels of DSB repair enzymes in aged tissues [13, 14] and senescent cells [15, 16]. Direct measurements of DNA repair functions in cells of young and old individuals showed that DSB repair declines in peripheral lymphocytes of aged human donors [17–19]; DSB repair by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) declines in multiple tissues of aged mice [20], rats [21, 22], and both NHEJ [23] and homologous recombination (HR) pathways decline in replicatively senescent cells [16].

Mutations in DSB repair genes lead to premature aging

Other strong evidence for the importance of DSB repair to aging comes from the fact that mutations in multiple genes involved in DSB repair lead to premature aging phenotypes. WRN protein, mutated in Werner syndrome, is involved in both HR and NHEJ (reviewed in [24–29]). Another human segmental progeroid syndrome, ataxia telangiectasia, is caused by defects in cellular responses to DSBs [30]. Mice with disruption in NHEJ genes Ku80 [31] and DNA-PKcs [32] show premature aging, as well as mice deficient in the ERCC1 gene involved in HR repair of DNA crosslinks [33, 34]. The deficiency in Lamin A, which causes Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) also results in impaired homologous recombination [35]. Sirt6 knockout mice display severe premature aging and genomic instability [36]. SIRT6 is involved in DSB repair by HR through the activation of PARP1 [37] and the deacetylation of CtIp [38], and in NHEJ through activating PARP1 [37] and facilitating DNA-PKcs [39], and SNF2H recruitment to chromatin [40]. In summary, DSB repair is the top pathway according to the number of mutations leading to premature aging.

Are naturally occurring mutations a driver of aging?

There is no direct evidence that naturally occurring somatic mutations are a cause of aging. Somatic mutation rates vary widely between tissues in mammals and are 13 to 75 times higher in the somatic cells than in the germline [41]. It was estimated that the body of a middle aged human might contain >1016 point mutations [41]. This estimate does not include insertions, deletions and rearrangements. Modern high throughput sequencing methods make it feasible to screen the entire human genome for new mutations, which can be readily done to detect the frequency of de novo mutations in pedigrees and clonally expanded mutations in tumors. However, somatic mutations are often unique for an individual cell and their frequency cannot be easily determined in DNA from aggregate cells or bulk tissue from young and aged organisms. To better understand the impact of somatic mutations on tissue function, new methods involving single cell sequencing are being developed that would allow mapping out the landscape of somatic mutations in individual cells within a tissue (reviewed in [42]). We anticipate that these methods will provide accurate estimates of somatic mutation frequencies in humans and in model organisms. It would then be possible to answer whether somatic mutation frequency negatively correlates with species’ longevity (reviewed in [43]).

Chromatin, mutations and aging

In addition to disrupting DNA sequence, mutations and genomic rearrangements affect chromatin structure. The higher order packaging of chromatin is now beginning to be understood [44–46]. Considering the complexity of chromatin organization, it is conceivable that an insertion or deletion can affect packaging and expression patterns of distant genes. Therefore, a mutation may have much broader consequences than could be envisioned by only considering the gene immediately affected. For example, transcription profiling and Hi-C analysis of the alteration of 16p11.2 genes implicated in autism spectrum disorders uncovered disrupted expression networks that involve multiple other genes and pathways [47]. To better understand the impact of mutations on age-related changes it would be important to measure the changes in chromatin organization after introduction of a deletion or insertion of different sizes in genomic DNA.

Chromatin organization undergoes dynamic changes during aging. Early work using HPLC measurements of 5-methyldeoxycytidine revealed a global reduction of CpG methylation with aging [48]. Recent studies applying genome-wide sequencing approaches found that CpG methylation decreases outside of CpG promoter islands [49]. In particular, repetitive sequences, tend to lose methylation with age [50]. In contrast, CpG methylation increases near promoters of genes involved in differentiation [49]. Older monozygotic twins show greater heterogeneity of methylation patterns as compared to young twins, suggesting an overall increase in genome somatic mosaicism with age [51]. Recently, a signature of 353 methylation sites was identified as a “methylation aging clock” that accurately predicts age across multiple human tissues [52].

At the level of chromatin, aging is associated with loss of heterochromatin and smoothening of patterns of transcriptionally active and repressed chromatin regions (for recent review, see [53]). This is associated with loss of repressive histone marks, and spreading of active histone marks. Loss of heterochromatin plays an important role in yeast replicative aging where overexpression of the silencer protein Sir2 extends lifespan [54]. Yeast aging is also associated with reduced histone expression and the appearance of nucleosome-free regions, while overexpression of histones H3 and H4 increases lifespan [55]. These observations led to the “heterochromatin loss model of aging”, according to which age-related chromatin loss and derepression of silenced genes leads to aberrant gene expression patterns and cellular dysfunction [56]. In Drosophila, lower levels of heterochromatin were associated with higher sensitivity to DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation, while increased levels of heterochromatin provide protection [57]. Therefore, age-related decline in DSB repair capacity may be further exacerbated by age-related heterochromatin loss leading to increased genomic instability with age.

Shared responsibilities: factors involved in DNA repair, chromatin and aging

Remarkably, several proteins regulating aging are also involved in chromatin maintenance and DSB repair. Before yeast Sir2 was found to promote yeast replicative lifespan, it was known as a mediator of chromatin silencing [58] and has also been reported to play a role in DSB repair [59–61]. The mammalian homologs of the yeast Sir2 include the nuclear localized proteins SIRT1 and SIRT6. Similar to the yeast Sir2, SIRT1 is recruited to the site of a DSB [62]. SIRT1 deficiency leads to impaired DSB repair by homologous recombination and loss of chromatin silencing. DNA damage was shown to cause a major redistribution of SIRT1 at the chromatin, leading to loss of pericentromeric repeats and changes in global transcription patters [62]. Similar transcriptional changes were observed in the aging brain, leading to a model which posits that DNA damage-induced redistribution of SIRT1 and other chromatin-modifying proteins is the driver of aging [62]. The other nuclear-localized sirtuin, SIRT6, is a H3K9 and H3K56 deacetylase, involved in chromatin silencing [63–65]. SIRT6 knockout results in massive loss of heterochromatin and activation of LINE1 retrotransposable elements [66]. SIRT6 plays a key role in DSB repair, being one of the early factors recruited to DSB sites [37] facilitating both HR and NHEJ repair pathways via multiple mechanisms [37–40] (described above). Similarly to SIRT1, DNA damage leads to redistribution of SIRT6 on chromatin, where SIRT6 moves from LINE1 promoters to DNA break sites leading to derepression of LINE1 elements [66].

The lamin A protein, implicated in HGPS as well as in the DNA damage response, is also linked to chromatin maintenance, as its main function is to provide a structural scaffold to the nucleus and its chromatin contents. Cells from HGPS patients show loss of constitutive heterochromatin and up-regulation of pericentric satellite repeat transcription [67]. Interestingly, lamin A interacts with both SIRT1 and SIRT6 proteins, and stimulates their enzymatic activities [68, 69].

PARP1 is another example of a protein involved in aging, DNA repair and chromatin. PARP1 is strongly activated by damaged DNA [70], where it begins to add poly-ADP ribose chains to itself and to core histones [71]. PARP1 is recruited early to DSBs and promotes removal of histones from DNA to enable DNA repair. PARP1 interacts with both SIRT1 and SIRT6 but with different consequences. While it was suggested that SIRT1 deacetylates and inactivates PARP1 [72], SIRT6 instead activates PARP1 by mono-ADP ribosylating it on lysine 521 residue [37]. PARP1 mutation leads to a mild premature aging phenotype in mice [73]. Interestingly, PARP1 activity measured in nuclear extracts from different mammalian species shows a positive correlation with species-specific life span [74].

The WRN protein, involved in DNA repair and aging (see above), was recently ascribed a novel function at maintaining silent chromatin [75]. WRN was shown to interact with the heterochromatin proteins SUV39H1 and HP1α, and the nuclear lamina-heterochromatin anchoring protein LAP2β. WRN deficiency was shown to lead to global loss of H3K9me3 and loss of heterochromatin [75].

The large number of aging genes being simultaneously involved in DNA repair and chromatin maintenance is striking. This suggests that these two pathways closely cooperate to promote longevity. However, this may still be considered as indirect evidence for a causal role of genome instability in aging.

How to prove that DNA damage, mutations and epigenetic dysregulation drive aging?

Loss of DSB repair function leading to premature aging provides indirect evidence that this pathway is involved in normal aging. However, the best proof that a pathway is a driver of aging is showing that enhanced function extends lifespan. With regard to DNA DSB repair, a multistep process involving numerous interacting proteins, enhancing the efficiency of the process is a challenging task. Simple overexpression of DSB repair enzymes such as WRN, Ku, or RAD51 disrupts the delicate balance between DNA processing factors, leading to cell death by apoptosis. Therefore, for a long time, it has been considered impossible to prove the causal role of DNA damage in aging.

However, it has now been shown possible to strongly enhance the DSB repair process by overexpressing an upstream factor, SIRT6, that facilitates chromatin remodeling and recruitment of the DSB repair machinery to a DSB site [16]. Remarkably, SIRT6 overexpression leads to a 15% extension of lifespan in male mice [76]. Lifespan extension in this mouse model was attributed to the metabolic effects of SIRT6 on IFG-1 levels [76]. However, the role of SIRT6 in stimulating DSB repair and maintenance of a youthful epigenome may also be an important factor in lifespan extension. Similarly, overexpression of SIRT1 in mouse hypothalamus has led to lifespan extension [77], which could also be in part caused by improved genome and epigenome maintenance in this vital organ. We anticipate that in the near future new animal models with improved DNA repair function will allow to directly test the DNA damage theory of aging.

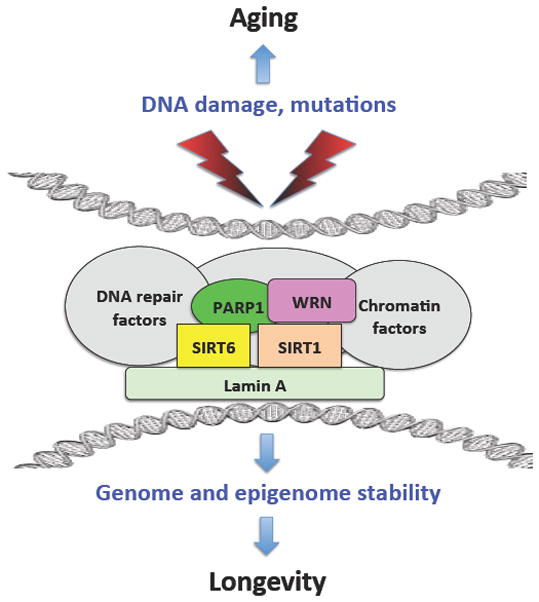

Figure 1. DNA repair and chromatin maintenance factors cooperate to promote longevity.

DNA damage and mutations compromise DNA sequences and chromatin organization leading to aging. Several proteins involved in longevity assurance have shared functions in DNA repair and chromatin maintenance. These proteins interact with each other and with other DNA repair and chromatin factors to maintain genome and epigenome stability and promote longevity.

Acknowledgments

The work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Aging, and by the Life Extension Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ness KK, Krull KR, Jones KE, Mulrooney DA, Armstrong GT, Green DM, Chemaitilly W, Smith WA, Wilson CL, Sklar CA, Shelton K, Srivastava DK, Ali S, Robison LL, Hudson MM. Physiologic frailty as a sign of accelerated aging among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4496–4503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White RR, Milholland B, de Bruin A, Curran S, Laberge RM, van Steeg H, Campisi J, Maslov AY, Vijg J. Controlled induction of DNA double-strand breaks in the mouse liver induces features of tissue ageing. Nature communications. 2015;6:6790. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolle MET, Giese H, Hopkins CL, Martus HJ, Hausdorf JM, Vijg J. Rapid accumulation of genome rearrangements in liver but not in brain of old mice. Nat Genet. 1997;17:431–434. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolle MET, Snyder WK, Gossen JA, Lohman PHM, Vijg J. Distinct spectra of somatic mutations accumulated with age in mouse heart and small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8403–8408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart GR, Oda Y, de Boer JG, Glickman BW. Mutation frequency and specificity with age in liver, bladder and brain of lacI transgenic mice. Genetics. 2000;154:1291–1300. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuart GR, Glickman BW. Through a glass, darkly: reflections of mutation from lacI transgenic mice. Genetics. 2000;155:1359–1367. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.3.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijg J. Somatic mutations and aging: a re-evaluation. Mutat Res. 2000;447:117–135. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis H, Crowley C. Chromosome aberrations in the liver cells in relation to the somatic mutation theory of aging. Radiat Res. 1963;19:337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey MJ, Moore DH, Briner JF, Lee DA, Olsen LA, Senft JR, Tucker JD. The effects of age and lifestyle factors on the accumulation of cytogenetic damage as measured by chromosome painting. Mutation Res. 1995;338:95–106. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(95)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker JD, Spruill MD, Ramsey MJ, Director AD, Nath J. Frequency of spontaneous chromosome aberrations in mice: effects of age. Mutat Res. 1999;425:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grist SA, McCarron M, Kutlaca A, Turner DR, Morley AA. In vivo human somatic mutation: frequency and spectrum with age. Mutat Res. 1992;266:189–196. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(92)90186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suh Y, Vijg J. Maintaining genetic integrity in aging: a zero sum game. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:559–571. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Um JH, Kim SJ, Kim DW, Ha MY, Jang JH, Chung BS, Kang CD, Kim SH. Tissue-specific changes of DNA repair protein Ku and mtHSP70 in aging rats and their retardation by caloric restriction. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:967–975. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ju YJ, Lee KH, Park JE, Yi YS, Yun MY, Ham YH, Kim TJ, Choi HM, Han GJ, Lee JH, Lee J, Han JS, Lee KM, Park GH. Decreased expression of DNA repair proteins Ku70 and Mre11 is associated with aging and may contribute to the cellular senescence. Exp Mol Med. 2006;38:686–693. doi: 10.1038/emm.2006.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seluanov A, Danek J, Hause N, Gorbunova V. Changes in the level and distribution of Ku proteins during cellular senescence. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1740–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao Z, Tian X, Van Meter M, Ke Z, Gorbunova V, Seluanov A. Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) rescues the decline of homologous recombination repair during replicative senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11800–11805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200583109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer PJ, Lange CS, Bradley MO, Nichols WW. Age-dependent decline in rejoining of X-ray-induced DNA double-strand breaks in normal human lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 1989;219:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(89)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh NP, Danner DB, Tice RR, Brant L, Schneider EL. DNA damage and repair with age in individual human lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 1990;237:123–130. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(90)90018-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garm C, Moreno-Villanueva M, Burkle A, Petersen I, Bohr VA, Christensen K, Stevnsner T. Age and gender effects on DNA strand break repair in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Aging Cell. 2013;12:58–66. doi: 10.1111/acel.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaidya A, Mao Z, Tian X, Spencer B, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. Knock-in reporter mice demonstrate that DNA repair by non-homologous end joining declines with age. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren K, de Ortiz SP. Non-homologous DNA end joining in the mature rat brain. J Neurochem. 2002;80:949–959. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vyjayanti VN, Rao KS. DNA double strand break repair in brain: reduced NHEJ activity in aging rat neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seluanov A, Mittelman D, Pereira-Smith OM, Wilson JH, Gorbunova V. DNA end joining becomes less efficient and more error-prone during cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7624–7629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400726101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohr VA. Human premature aging syndromes and genomic instability. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:987–993. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Oshima J. Werner Syndrome. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2002;2:46–54. doi: 10.1155/S1110724302201011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fry M. The Werner syndrome helicase-nuclease--one protein, many mysteries. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2002;2002:re2. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2002.13.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:169–178. doi: 10.1038/nrc1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Opresko PL, Cheng WH, von Kobbe C, Harrigan JA, Bohr VA. Werner syndrome and the function of the Werner protein; what they can teach us about the molecular aging process. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:791–802. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comai L, Li B. The Werner syndrome protein at the crossroads of DNA repair and apoptosis. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiloh Y, Kastan MB. ATM: genome stability, neuronal development, and cancer cross paths. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;83:209–254. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(01)83007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel H, Lim DS, Karsenty J, Finegold M, Hasty P. Deletion of Ku 86 cases erly onset of senescence in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10770–10775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espejel S, Martin M, Klatt P, Martin-Caballero J, Flores JM, Blasco MA. Shorter telomeres, accelerated ageing and increased lymphoma in DNA-PKcs-deficient mice. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:503–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weeda G, Donker I, de Wit J, Morreau H, Janssens R, Vissers CJ, Nigg A, van Steeg H, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH. Disription of mouse ERCC1 results in novel repair syndrome with growth failure, nulear abnormalities and senescence. Curr Biol. 1997;7:427–439. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niedernhofer LJ, Garinis GA, Raams A, Lalai AS, Robinson AR, Appeldoorn E, Odijk H, Oostendorp R, Ahmad A, van Leeuwen W, Theil AF, Vermeulen W, van der Horst GT, Meinecke P, Kleijer WJ, Vijg J, Jaspers NG, Hoeijmakers JH. A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature. 2006;444:1038–1043. doi: 10.1038/nature05456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu B, Wang J, Chan KM, Tjia WM, Deng W, Guan X, Huang JD, Li KM, Chau PY, Chen DJ, Pei D, Pendas AM, Cadinanos J, Lopez-Otin C, Tse HF, Hutchison C, Chen J, Cao Y, Cheah KS, Tryggvason K, Zhou Z. Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging. Nat Med. 2005;11:780–785. doi: 10.1038/nm1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mostoslavsky R, Chua KF, Lombard DB, Pang WW, Fischer MR, Gellon L, Liu P, Mostoslavsky G, Franco S, Murphy MM, Mills KD, Patel P, Hsu JT, Hong AL, Ford E, Cheng HL, Kennedy C, Nunez N, Bronson R, Frendewey D, Auerbach W, Valenzuela D, Karow M, Hottiger MO, Hursting S, Barrett JC, Guarente L, Mulligan R, Demple B, Yancopoulos GD, Alt FW. Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of mammalian SIRT6. Cell. 2006;124:315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao Z, Hine C, Tian X, Van Meter M, Au M, Vaidya A, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. SIRT6 promotes DNA repair under stress by activating PARP1. Science. 2011;332:1443–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.1202723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaidi A, Weinert BT, Choudhary C, Jackson SP. Human SIRT6 promotes DNA end resection through CtIP deacetylation. Science. 2010;329:1348–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1192049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39.McCord RA, Michishta E, Hong T, Berber E, Boxer LD, Kusumoto R, Guan S, Shi X, Gozani O, Burligame AL, Bohr VA, Chua KF. SIRT6 stabilizes DNA-dependent protein kinase at chromatin for DNA double-strand break repair. Aging. 2009;1:109–121. doi: 10.18632/aging.100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toiber D, Erdel F, Bouazoune K, Silberman DM, Zhong L, Mulligan P, Sebastian C, Cosentino C, Martinez-Pastor B, Giacosa S, D’Urso A, Naar AM, Kingston R, Rippe K, Mostoslavsky R. SIRT6 recruits SNF2H to DNA break sites, preventing genomic instability through chromatin remodeling. Mol Cell. 2013;51:454–468. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch M. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet. 2010;26:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vijg J. Somatic mutations, genome mosaicism, cancer and aging. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;26:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Zhang Z, Gladyshev VN, Vijg J. Comparative genetics of longevity and cancer: insights from long-lived rodents. Nature reviews. 2014;15:531–540. doi: 10.1038/nrg3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorkin DU, Leung D, Ren B. The 3D genome in transcriptional regulation and pluripotency. Cell stem cell. 2014;14:762–775. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO, Sandstrom R, Bernstein B, Bender MA, Groudine M, Gnirke A, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Mirny LA, Lander ES, Dekker J. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, Sanborn AL, Machol I, Omer AD, Lander ES, Aiden EL. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159:1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blumenthal I, Ragavendran A, Erdin S, Klei L, Sugathan A, Guide JR, Manavalan P, Zhou JQ, Wheeler VC, Levin JZ, Ernst C, Roeder K, Devlin B, Gusella JF, Talkowski ME. Transcriptional consequences of 16p11.2 deletion and duplication in mouse cortex and multiplex autism families. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:870–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singhal RP, Mays-Hoopes LL, Eichhorn GL. DNA methylation in aging of mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 1987;41:199–210. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(87)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, Nelson HH, Karagas MR, Padbury JF, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ, Yeh RF, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bollati V, Schwartz J, Wright R, Litonjua A, Tarantini L, Suh H, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Baccarelli A. Decline in genomic DNA methylation through aging in a cohort of elderly subjects. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Talens RP, Christensen K, Putter H, Willemsen G, Christiansen L, Kremer D, Suchiman HE, Slagboom PE, Boomsma DI, Heijmans BT. Epigenetic variation during the adult lifespan: cross-sectional and longitudinal data on monozygotic twin pairs. Aging Cell. 2012;11:694–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology. 2013;14:R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Brunet A. Epigenetic regulation of ageing: linking environmental inputs to genomic stability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:593–610. doi: 10.1038/nrm4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaeberlein M, McVey M, Guarente L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2570–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feser J, Truong D, Das C, Carson JJ, Kieft J, Harkness T, Tyler JK. Elevated histone expression promotes life span extension. Mol Cell. 2010;39:724–735. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsurumi A, Li WX. Global heterochromatin loss: a unifying theory of aging? Epigenetics. 2012;7:680–688. doi: 10.4161/epi.20540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan SJ, Lim SJ, Shi S, Dutta P, Li WX. Unphosphorylated STAT and heterochromatin protect genome stability. FASEB J. 2011;25:232–241. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Gottschling DE. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1991;66:1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boulton SJ, Jackson SP. Components of the Ku-dependent non-homologous end-joining pathway are involved in telomeric length maintenance and telomeric silencing. EMBO J. 1998;17:1819–1828. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin SG, Laroche T, Suka N, Grunstein M, Gasser SM. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell. 1999;97:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mills KD, Sinclair DA, Guarente L. MEC1-dependent redistribution of the Sir3 silencing protein from telomeres to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 1999;97:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oberdoerffer P, Michan S, McVay M, Mostoslavsky R, Vann J, Park SK, Hartlerode A, Stegmuller J, Hafner A, Loerch P, Wright SM, Mills KD, Bonni A, Yankner BA, Scully R, Prolla TA, Alt FW, Sinclair DA. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135:907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michishita E, McCord RA, Berber E, Kioi M, Padilla-Nash H, Damian M, Cheung P, Kusumoto R, Kawahara TL, Barrett JC, Chang HY, Bohr VA, Ried T, Gozani O, Chua KF. SIRT6 is a histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylase that modulates telomeric chromatin. Nature. 2008;452:492–496. doi: 10.1038/nature06736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang B, Zwaans BM, Eckersdorff M, Lombard DB. The sirtuin SIRT6 deacetylates H3 K56Ac in vivo to promote genomic stability. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2662–2663. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michishita E, McCord RA, Boxer LD, Barber MF, Hong T, Gozani O, Chua KF. Cell cycle-dependent deacetylation of telomeric histone H3 lysine K56 by human SIRT6. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2664–2666. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Meter M, Kashyap M, Rezazadeh S, Geneva AJ, Morello TD, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nature communications. 2014;5:5011. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shumaker DK, Dechat T, Kohlmaier A, Adam SA, Bozovsky MR, Erdos MR, Eriksson M, Goldman AE, Khuon S, Collins FS, Jenuwein T, Goldman RD. Mutant nuclear lamin A leads to progressive alterations of epigenetic control in premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8703–8708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602569103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghosh S, Liu B, Wang Y, Hao Q, Zhou Z. Lamin A Is an Endogenous SIRT6 Activator and Promotes SIRT6-Mediated DNA Repair. Cell reports. 2015;13:1396–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu B, Ghosh S, Yang X, Zheng H, Liu X, Wang Z, Jin G, Zheng B, Kennedy BK, Suh Y, Kaeberlein M, Tryggvason K, Zhou Z. Resveratrol rescues SIRT1-dependent adult stem cell decline and alleviates progeroid features in laminopathy-based progeria. Cell Metab. 2012;16:738–750. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D’Amours D, Desnoyers S, D’Silva I, Poirier GG. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J. 1999;342(Pt 2):249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Messner S, Altmeyer M, Zhao H, Pozivil A, Roschitzki B, Gehrig P, Rutishauser D, Huang D, Caflisch A, Hottiger MO. PARP1 ADP-ribosylates lysine residues of the core histone tails. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6350–6362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rajamohan SB, Pillai VB, Gupta M, Sundaresan NR, Birukov KG, Samant S, Hottiger MO, Gupta MP. SIRT1 promotes cell survival under stress by deacetylation-dependent deactivation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4116–4129. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00121-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piskunova TS, Zabezhinskii MA, Popovich IG, Semenchenko AV, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE, Tyndyk ML, Anisimov VN. Features of carcinogenesis and aging in knockout male mice PARP-1. Voprosy onkologii. 2010;56:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grube K, Burkle A. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in mononuclear leukocytes of 13 mammalian species correlates with species-specific life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:11759–11763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang W, Li J, Suzuki K, Qu J, Wang P, Zhou J, Liu X, Ren R, Xu X, Ocampo A, Yuan T, Yang J, Li Y, Shi L, Guan D, Pan H, Duan S, Ding Z, Li M, Yi F, Bai R, Wang Y, Chen C, Yang F, Li X, Wang Z, Aizawa E, Goebl A, Soligalla RD, Reddy P, Esteban CR, Tang F, Liu GH, Belmonte JC. Aging stem cells. A Werner syndrome stem cell model unveils heterochromatin alterations as a driver of human aging. Science. 2015;348:1160–1163. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kanfi Y, Naiman S, Amir G, Peshti V, Zinman G, Nahum L, Bar-Joseph Z, Cohen HY. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature. 2012;483:218–221. doi: 10.1038/nature10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Satoh A, Brace CS, Rensing N, Cliften P, Wozniak DF, Herzog ED, Yamada KA, Imai S. Sirt1 extends life span and delays aging in mice through the regulation of Nk2 homeobox 1 in the DMH and LH. Cell Metab. 2013;18:416–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]