Abstract

Alcoholic liver diseases (ALD) comprise a spectrum of clinical disorders and changes in liver tissue that can be detected by pathology analysis. These range from steatosis to more severe signs and symptoms of liver disease associated with inflammation, such as those observed in patients with alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis. Although the relationship between alcohol consumption and liver disease is well established, severe alcohol-related morbidities develop in only a minority of people who consume alcohol in excess. Inter-individual differences in susceptibility to the toxic effects of alcohol have been extensively studied—they include pattern of alcohol consumption, sex, environmental factors (such as diet), and genetic factors, which vary widely among different parts of the world. ALD is becoming more common in many parts of Asia but is decreasing in Western Europe. Treatment approaches, including availability of medications, models of care, and approach to transplantation, differ among regions.

Keywords: Clinical profiles, Alcoholic liver disease, Asia, Europe, North America

Alcohol is consumed worldwide and has been used in many cultures for centuries1. When consumed in excess, it can cause diseases that place social and economic burdens on societies. In 2012, about 3.3 million deaths, or 5.9% of all global deaths, were attributed to alcohol consumption1. Alcohol-related health disorders are generally determined by the volume and quality of alcohol consumed and the pattern of drinking1.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) has been estimated to account for 48% of all deaths from cirrhosis2. It comprises a spectrum of disorders and pathologic changes in individuals with acute and chronic alcohol consumption, ranging from alcoholic steatosis to alcoholic hepatitis (AH) and cirrhosis. Alcoholic steatosis, once considered benign, is now recognized as a condition that may lead to advanced liver disease or cirrhosis3. Development of alcoholic steatosis depends on the dose and duration of alcohol intake. However, it is difficult to establish whether there is a threshold of alcohol intake required for development of fatty liver. Alcoholic steatosis can develop within 2–3 weeks in subjects who consume alcohol in the excessive range (120–150 g/day)4, but can be reversed with abstinence. If alcohol consumption continues, some patients develop AH—the most florid manifestation of ALD, associated with high mortality5. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients who drink alcohol excessively develop cirrhosis in their lifetime6.

Mortality from alcohol-associated cirrhosis in different countries correlates with per capita alcohol consumption7, 8. With recent changes in the economies and increases in average incomes in developing regions of the world, there has been a rapid rise in per capita alcohol consumption in countries such as China and India9,10. In fact, alcohol consumption is increasing faster in China than other parts of the world9, 11. The per capita consumption of alcohol in India has increased by 55% over the past decade10. Based on these statistics, it is expected that the prevalence of ALD will increase globally. We review the similarities and differences in epidemiologic factors, patterns of alcohol consumption, risk factors, and clinical features of patients with ALD in different geographic regions, comparing countries in Asia to those in Europe and the United States (US).

Patterns of Alcohol Consumption

In comparing similarities and differences of ALD among different regions of the world, it is important to understand current and evolving patterns of global alcohol consumption. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that in 2010, total alcohol per capita consumption was highest in the developed world—mostly in the Northern Hemisphere12. Eastern Europe had the highest per capita consumption per year, with 15.7 liters per person (8.1 liters per woman and 24.9 liters per man)2. The US had per capita consumption with 9.2 liters per person (4.9 liters per woman and 13.6 liters per man)12. By comparison, per capita consumption values for China, India, Republic of Korea, and Japan were 6.7 liters per person (2.2 liters per woman and 10.9 liters per man), 4.3 liters per person (0.5 liters per woman and 8 liters per man), 12.3 per person (3.9 in woman and 21 in man) and 7.2 liters per person (4.2 liters per woman and 10.4 liters per man), respectively12. The total adult per capita consumption in 2010, in liters of pure alcohol, is shown in Fig 113.

Figure 1.

Total adult per-capita consumption of pure alcohol in Asia, Europe, and North America (modified from ref 13)

In general, men that consume up to 2 drinks/day (1 drink/day for women) are defined as moderate drinkers14. Drinking at this level does not increase risk of organ injury. Daily consumption beyond these limits is considered to be heavy drinking, which can have adverse health and social outcomes15. This definition of chronic drinkers does not include the pattern of binge drinking—the definition varies among different geographic regions. The US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism proposed a definition of binge drinking as the consumption of 5 or more drinks for men (4 or more drinks for women) within 2 hrs16. In the United Kingdom (UK), binge drinking is defined as consuming 8 units or more for men (6 units or more for women; ~5 or 4 American standard drinks, respectively)17.

The WHO uses the patterns of drinking score (a composite measure of drinking patterns) to determine how people drink, instead of how much they drink, on a scale of 1 (least risky pattern of drinking) to 5 (most risky pattern of drinking)18. Parameters used to create this indicator include quantity of alcohol consumed per occasion, festive drinking, proportion of drinking events that result in becoming drunk, proportion of drinkers who drink daily, drinking with meals, and drinking in public places. Eastern Europe had the highest pattern of drinking score (4.9)2, whereas the score for the US was 2—similar to countries in Asia such as China, Japan, and Singapore18. India and Republic of Korea each had a score of 3.

In the US in 2013, 86.8% of people 18 years or older reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their lifetime. Of these people, 24.6% stated that they engaged in binge drinking and 6.8% reported that they engaged in heavy drinking in the past month19. The percentage of men who had at least 1 heavy drinking day in the past year decreased from 31.6% in 1997 to 27.8% in 2006, then increased to 32.4% in 2009. Since the time period of 2009 to 2014, there has been no decrease or increase20. In the UK, the Health Survey for England reported that 57% of young men were binge drinkers21. Most European countries have had the same trend toward an increase in binge drinking, even in southern countries14. In Asia, alcohol consumption in China is increasing faster than other parts of the world11. A recent national survey found 56% of men and 15% of women to be current drinkers. Among them, heavy drinking was reported in 63% of men and 51% of women, whereas binge drinking occurred for 57% of men and 27% of women11. Alcohol use disorders (AUDs), defined as harmful patterns of drinking such as alcohol dependence and abuse, have become a frequent problem linked to disturbances in mental and physical health and in social functioning in China11. There was a dramatic increase in the proportion of individuals with AUDs, from 0.45% in mid-1980s to 3.4% in mid-1990s,11 with the life-time prevalence of 9% during the years of 2001 to 200522. India has also increased alcohol use, from 3.6 to 4.3 liters/person/year13.

Unrecorded alcohol use varies greatly between countries, from below 10% in wealthy and highly regulated nations to above 50% in less well-developed nations23. Official statistics are typically based on taxation records of recorded consumption—these substantially underestimate total consumption, particularly in the developing world24. The chief concern regarding home brew is access to beverages with high alcohol content at relatively low cost. As a secondary concern, they may be contaminated with methanol, leading to life-threatening poisonings or consumption of other hepatotoxins, such as polyhexamethyleneguanidine, which has been linked to an outbreak of acute cholestatic liver injury in Russia23.

Prevalence and Burden of ALD

Mortality from ALD, regardless of country, correlates with per capita of alcohol consumption7, 8. Overall consumption or average volume of alcohol consumed has been the usual measure of exposure, and that there is a dose-response relationship between the volume of alcohol consumed and risk of ALD25. A meta-analysis found that consumption of more than 25 g/day increased the relative risk of cirrhosis26. This threshold is in accordance with that from a study showing a significant increase in risk of cirrhosis with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day27. A separate study showed that recent drinking, rather than earlier in life consumption, was associated with the risk of alcohol-associated cirrhosis28.

Although studies correlate average volume of alcohol consumption with ALD, several studies have associated risk with drinking patterns29. Binge drinking (too much too fast) and chronic excessive drinking (too much too often) are significant risk factors for ALD27, 30. In addition to the quantity of alcohol consumption, there is controversy over whether risk of ALD depends on the type and pattern of alcohol intake, independent of absolute levels of consumption. Some studies have found red wine drinkers to have a lower risk of ALD than consumers of other beverages28, 31. However, other studies produced contradicting results32, 33.

AH

The precise incidence and prevalence of AH are unknown, partly because AH may be completely asymptomatic and thus remain undiagnosed. The available data on the burden of AH from each geographic region are difficult to compare, primarily because of the disparity in the studied population. In a population-based cohort study of all patients with a hospital discharge diagnosis of AH in Denmark from 1999 to 2008, the overall incidence rate for AH was 36.6 per million/year34. The incidence was higher in men compared to women (46.4 vs 26.9 per million/year, respectively). The incidence increased for men and women during the decade of study34. A study in France analyzed liver biopsies from 1604 subjects with chronic heavy alcohol use. Of these, 119 subjects (7.4%) had acute AH and 179 subjects (11%) had AH with cirrhosis35. In the US, total cases of AH-related hospitalization increased from 249,884 (0.66% of total admissions) in 2002 to 326,403 (0.83% of total admissions) in 2010, based on analysis of National Inpatient Sample data36. AH was found in ~29% of hospitalized patients with ALD in India37.

Alcohol-associated cirrhosis

The global burden of ALD, measured by deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), has been recently reported2. DALYs are an indicator of overall disease burden, providing the number of years lost due to poor health, disability, or early death. Globally, alcohol contributed 4.5% of all DALYs in 2004, making it the third leading risk factor for disease (after childhood underweight and unsafe sex), ahead of tobacco and other established risk factors38. Alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis was responsible for 493,300 deaths (156,900 deaths in women and 336,400 deaths in men) and 14,544,000 DALYs (4,112,000 DALYs for women and 10,432,000 DALYs for men) in 2010. It accounts for 0.9% of all global deaths (0.7% for women and 1.2% for men), 0.6% of all global DALYs (0.4% for women and 0.8% for men), 47.9% of all liver cirrhosis deaths (46.5% for women and 48.5% for men), and 46.9% of all liver cirrhosis DALYs (44.5% for women and 47.9% for men)2. There were 211.1 DALYs per 100,000 people caused by liver cirrhosis attributable to alcohol consumption in 20102. Central Asia experienced the greatest number of alcohol attributable liver cirrhosis DALYs per 100,000 people for men and women, with 546.0 DALYs per 100,000 people (435.1 DALYs per 100,000 women, and 655.0 DALYs per 100,000 men). Eastern Europe had the second highest rate of liver cirrhosis DALYs due to alcohol consumption, with 456.1 DALYs per 100,000 people2. Alcohol-attributable DALYS caused by liver cirrhosis in each geographic region is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Alcohol-attributable DALYs Attributed to Cirrhosis in 2010

| Regions | Women | Men | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DALYs | % of all DALYs | %of all alcohol-attributable DALYs | DALYs | % of all DALYs | %of all alcohol-attributable DALYs | DALYs | % of all DALYs | %of all alcohol-attributable DALYs | |

| Asia, Pacific (high income) | 106,000 | 0.5 | 16.6 | 359000 | 1.5 | 14.4 | 465000 | 1.1 | 14.8 |

| Asia, Central | 167000 | 1.3 | 17.9 | 231000 | 1.4 | 10.3 | 398000 | 1.4 | 12.6 |

| Asia, East | 424000 | 0.3 | 9.4 | 1625000 | 0.8 | 9.1 | 2049000 | 0.6 | 9.2 |

| Asia, South | 657000 | 0.2 | 15.2 | 2142000 | 0.6 | 13.3 | 2799000 | 0.4 | 13.7 |

| Asia, Southeast | 174000 | 0.2 | 13.5 | 923000 | 0.9 | 14.9 | 1097000 | 0.6 | 14.6 |

| Australasia | 8000 | 0.3 | 6.8 | 19000 | 0.6 | 6.5 | 28000 | 0.5 | 6.6 |

| Europe, Central | 173000 | 1.0 | 11.9 | 473000 | 2.2 | 11.6 | 646000 | 1.7 | 11.7 |

| Europe, Eastern | 531000 | 1.3 | 7.0 | 554000 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 1085000 | 1.2 | 5.0 |

| Europe, Western | 383000 | 0.7 | 13.3 | 793000 | 1.3 | 11.5 | 1176000 | 1.0 | 12.0 |

| North America | 314000 | 0.7 | 13.3 | 551000 | 1.2 | 10.1 | 865000 | 1.0 | 11.0 |

Note: modified from ref 2

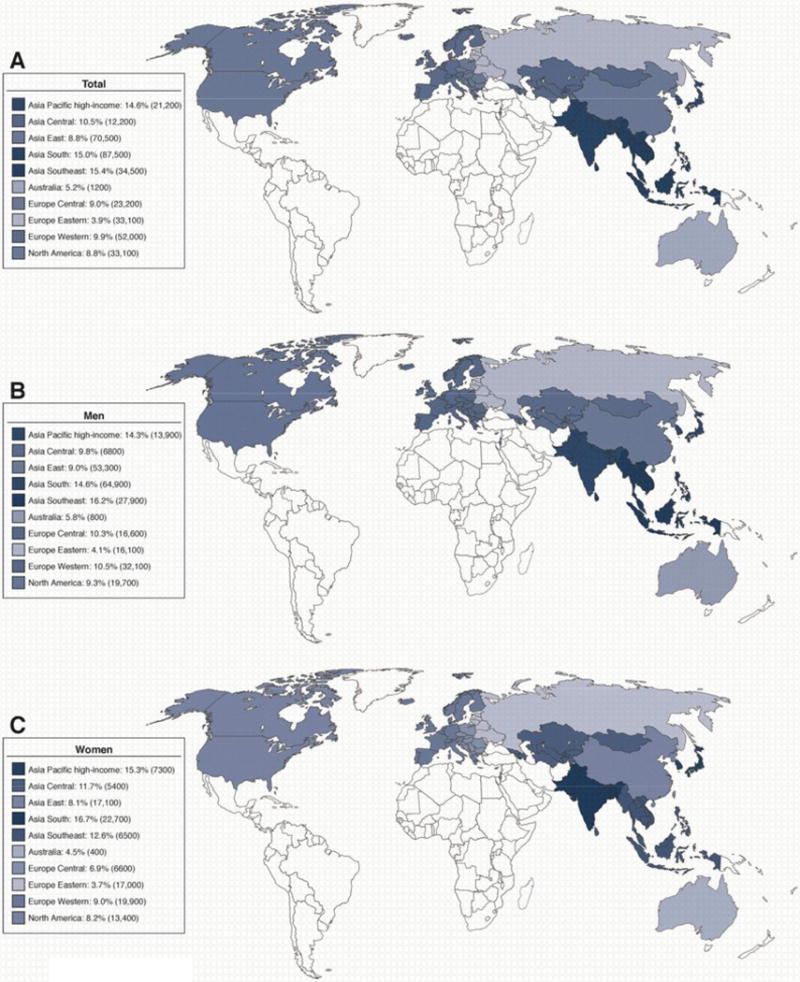

The overall alcohol-attributable deaths from cirrhosis among different geographic regions is shown in Fig 2 (ref 2). Among western countries, time trends in mortality over the past 3 decades have varied. Countries such as Austria, France, Germany, and Hungary have had a decrease in mortality, whereas Finland, Ireland, and the UK have had increases in mortality39. In the UK and Scotland, there was a 5-fold increase in cirrhosis mortality among men and 4-fold increase among women from 1950 through 200040, 41. In the past 40 years, the UK has seen substantial reductions in the mortality of most common diseases whereas cirrhosis mortality has risen 5-fold—a striking exception42.

Figure 2.

Overall alcohol-attributable deaths caused by cirrhosis in different geographic regions (modified from ref 2)

Factors Associated With ALD

In most of the studies from the US and Europe, the mean age of patients at the time of diagnosis with ALD has been 45–55 years old36, 35, 43, 44. Data from the US using the National Hospital Discharge Survey 2010 and National Inpatient Sample showed that most patients with a diagnosis of ALD were 45–64 years old,45 with the average age of 53 years36. The age of diagnosis of patients with ALD in the US is similar to that from several countries in Europe35, 43, 44. The mean age at which ALD is detected in the western countries is older than that from a population-based study in China, which found most subjects with ALD to be 36–48 years old46. In a separate population-based study from China, Wang et al observed a trend of an increase in incidence of ALD as the population increased in age, until 50 years old. The highest prevalence rate of ALD was found in people 40–49 years old47. The age differences between each demographic region are likely due to the care setting from which data were collected (population vs hospital-based), age structure of the population itself, and patterns of alcohol consumption. In fact, there were no differences in the mean age of hospitalized ALD patients in each geographic location48–50.

The greater vulnerability of women and lower safe limits for consumption have long been recognized25. However, cases reported from each geographic region have indicated a higher prevalence of ALD and mortality in men2,35, 36, 46, 49. This could be because men typically drink more than women, have a greater proportion of heavy drinkers and alcoholics, regardless of geographic locations51. The longstanding sex difference in alcohol consumption has decreased in Western countries. In the UK, mortality from ALD has increased more in women than in men with a 7-fold increase in women younger than 30 years41.

Socioeconomic status

Rising income among people in the developing world increases their access to alcohol and in turn, associated morbidities, including ALD52, 53. However, the link between socioeconomic status and ALD is complex. Multiple factors are involved, such as market liberalization, increased advertising, and growing affluence; these have made alcohol more available in general54 and to people of low socioeconomic status, in particular55. Alcohol-related problems have increased rapidly in this group. One study found significant increases in risks of cirrhosis-associated mortality among patients who are not married or are urban residents, unemployed, or with lower levels of education and family income56. An analysis of the US National Inpatient Sample showed that patients hospitalized for AH come primarily from low-income households36. In China, the production and consumption of alcoholic beverage have increased with the country’s rapid economic growth9, 47. A study from North-Eastern China showed that that people with a low level of education or income, or people who are unmarried, have a high risk of ALD47. The findings which are similar to those reported from the US56.

Race and ethnicity

There are few data on the effects of race and ethnicity on alcohol-associated disease from Asian countries, primarily because of their homogenous populations. In the US, age-adjusted rates of alcohol-associated cirrhosis are higher for Blacks than for Whites51, and mortality is highest in Hispanic groups57. However, these findings cannot be attributed to higher alcohol consumption among Hispanics and Blacks than Whites51—alcohol consumption among Blacks has been less than or comparable with that of Whites. The reasons for the differences in cirrhosis and mortality are not clear, but could involve the limited access of Blacks and Hispanics to alcohol rehabilitation, or hepatitis C virus infection, which is more common in Hispanics51.

Body mass index (BMI) and obesity

In an epidemiologic study from the US, overweight and obesity were found to increase risk for alcohol-related abnormalities in aminotransferase activity58. A large study from France identified excess body weight for at least 10 years as a risk factor for AH and alcohol-associated cirrhosis35. A study from Scotland found that high BMI and excessive alcohol intake increased mortalities from liver disease59. Similar observations have been made in studies in Asia. In a large prospective study of 1270 subjects from China, 16% had BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Though the average daily alcohol intake in this group was lower than those with BMI<25, ALD morbidity in this group was 11.5%, compared to ~5% in those with normal BMIs. The presence of obesity was an independent predictor for ALD60.

Genetic factors

Variants in genes encoding members of the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) family affect their ability to metabolize alcohol. Levels of ADH enzymatic activity determine risk for alcohol dependence and susceptibility to alcohol-induced liver injury30. Individuals carrying variants that encode enzymes with high levels of activity (ADH1B*2 and ADH1C*1 alleles) are believed to be at increased risk for ALD, due to higher levels of acetaldehyde exposure61. In a Japanese cohort of alcoholic men, the ADH1B*2 allele was associated with greater risk of cirrhosis compared with the ADH1B*1 allele62. However, a large study of 876 Caucasian individuals (from Spain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Poland) did not detect a significant association between ADH1C variants and alcohol-associated cirrhosis, although it did find that ADH1B*2 reduced risk for excessive alcohol intake63. A recent meta-analysis confirmed this association in Asian populations but found no association in Western populations64. This could be because ADH1B*2 is a rare allele in Caucasians; some smaller studies found no patients to carry this allele. Approximately 40%–50% of Chinese people are homozygous or heterozygous for the ALDH2*2 allele and have low ALDH2 activity65. These individuals have high blood concentrations of acetaldehyde after alcohol consumption and may be more susceptible to liver injury.

Alcohol can be metabolized, to a lesser extent, by cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1 (CYP2E1). CYP2E1 is an inducible enzyme; its activity can increase up to 20-fold following continuous alcohol consumption66. The c1 and c2 alleles of CYP2E166 affect activity of the gene product. The product of the CYP2E1*5 (c2) allele has higher activity than that of c1 allele, and could lead to a higher exposure of the liver to acetaldehyde and reactive oxygen species67. In a study of a Caucasian population in the West, the c2 allele was associated with increased risk of ALD in subjects with higher cumulative levels of alcohol consumption. However, the risk was only in subjects who also had the ADH1C*2 allele68. Interestingly, another polymorphism in CYP2E1, Taq I, is associated with reduced susceptibility to ALD, although this allele does not directly affect alcohol metabolism69. Several studies from Japan and Korea have searched for associations between the polymorphisms in CYP2E1 and ALD without positive results70, 71. A study of Chinese of Han, Mongol, and Chaoxian nationalities found a positive association between the c2 genotype and ALD72.

Altered activities of cytokines and proteins that respond to endotoxin are involved in the pathogenesis of ALD73, so variants in their genes could affect susceptibility to ALD. CD14 is a coreceptor for the toll-like receptor 4, which interacts with bacterial lipopolysaccharide in the portal bloodstream74, 75. A C/T polymorphism at position −159 in the promoter region of the CD14 gene, producing a TT genotype, is associated with increased expression of CD1476. In a study of autopsy results from 442 men in Finland, with valid alcohol consumption data, the TT genotype increased risk for advanced ALD by almost 2.5-fold and cirrhosis by almost 3.5-fold, compared to men without the TT genotype77. Individuals with the TT polymorphism at position −159 in the promoter region of the CD14 are therefore at high for cirrhosis77. Interestingly, a study from Taiwan did not associate this polymorphism with ALD78.

A C/A polymorphism at position −627 in the promoter of the interleukin-10 (IL10) gene has been associated with decreased expression, resulting in an increase inflammatory response79. Researchers investigated the prevalence of this polymorphism among 287 heavy drinkers with biopsy-proven advanced ALD, 107 heavy drinkers with no evidence of liver disease or steatosis from biopsy analyses, and 227 individuals without liver disease (controls). At this position in IL10, 50% of patients with advanced ALD had a least 1 allele with the A C/A polymorphism, compared with 33% of controls and 34% of drinkers with no or mild disease. These findings indicate an association between genetic variants that reduce expression or activity of IL10 and ALD79. However, subsequent studies of polymorphisms in IL10 in other European populations produced contradictory results80, 81. A study from the Bengali population of Eastern India associated a genetic variant of IL10 with alcoholic cirrhosis82 as did smaller study from Taiwan83.

The patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 22 and encodes adiponutrin. This protein has triglyceride lipase and acylglycerol transacetylase activities, and is expressed in response to energy mobilization and storage of lipid droplets84. A genome-wide screen for non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in Hispanic, African, and European Americans participating in the Dallas Heart Study associated a variant in PNPLA3 (rs738409 [M148I]) with hepatic fat content, measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy85. PNPLA3 rs738409 increased risk for alcoholic cirrhosis 2.25-fold86. The association between PNPLA3 variants and ALD was confirmed in a German cohort87 and patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis of European descent88. In this study, carriers of PNPLA3 rs738409 (G/G) were found to be at high risk for progression of clinically silent to overt ALD. In total, 26.6% of the population-attributable risk for the progression of early to advanced ALD were found to be conferred by this risk allele87. A recent meta-analysis clearly associated the rs738409 variant with alcoholic liver cirrhosis89. A number of studies have associated variants in PNPLA3 with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in different regions of Asia90, 91 but there are few data on ALD92. A small study from India (of 60 patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis) found that the rs738409 polymorphism increased risk for ALD 2.1-fold92. However, further studies are needed to determine the association between PNPLA3 and ALD in Asian populations.

Clinical Presentation

We have no evidence to support significant differences in the clinical presentation of ALD among patients in Asia, Europe, or North America. Most patients present with signs and symptoms related to portal hypertension or cirrhosis. Jaundice, as expected, is common among patients presenting with AH93.

Treatment of AUD

The most powerful determinants of alcohol use are price, availability, and promotion. Public policies that address these factors can influence population level use of alcohol and in turn rates of cirrhosis and other health disorders. The WHO has endorsed a global strategy to reduce harmful use of alcohol that includes 10 priority actions for nations (see Fig 3) and 4 international priority actions94. However, the strength of public policy varies strikingly among nations and over time.

Figure 3.

WHO Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful us of alcohol (modified from ref 94)

Internationally, there is evidence that strength of public policy correlates with levels of consumption95. For example, during the alcohol prohibition era in the USA, cirrhosis mortality was reduced by approximately half51. In Russia, alcohol-attributable mortality varied by year as national controls were imposed and relaxed; in several recent years, alcohol caused more than half of all deaths among Russians 15–54 years old96. Current policies in China and India promote increased use—alcohol is cheap and there is widespread access to high-strength alcoholic beverages97. As prosperity has increased, the global alcohol industry has increased its focus on sales in these regions, but this may have adverse effects on health. Many believe that the alcohol industry is currently focusing on women and young people98, who are most vulnerable to alcohol-related disorders, including ALD. China has implemented several changes in alcohol taxes, for general economic reasons, and these have been linked to changes in both consumption and alcohol-associated harm99. These policy approaches could reduce the burden of ALD, but a recent review reported a dearth of alcohol policy research in China100. An increase in alcohol tax in Taiwan in 2002 reduced hospital expenditures on ALD101.

There has been a recent significant review of the effects of ALD and liver disease in general in the UK42. The review recommended a minimum price on alcoholic beverages—particularly for cheap wine—health warnings on packages (similar to tobacco), a volume-based tax, reduction in the number of liquor outlets, restrictions on advertising, and improved screening and access to treatment for alcohol problems42. Such policies have been introduced in some European countries. However, there seems to be resistance in the UK to their implementation—it has been proposed that this is related to pressure on government from the alcohol industry. Similar recommendations have been made elsewhere, and there has been comparable reluctance to introduce alcohol control policies in India98, China11, and the US102.

Alcohol use can be detected by clinical and laboratory tests, but screening instruments for alcohol disorders have been developed; these are more sensitive than routine care and are cheap and readily available. The AUD Identification Test (AUDIT) developed by the WHO in the 1990s is the most widely used but was validated in the English language. AUDIT has been translated and validated into a number of languages including Tamil103, Konkani (the language of Goa)104, Chinese105, and Korean106. Other screening measures have not been disseminated into many languages other than English.

The most widely available treatment involves provision of brief advice to reduce or stop drinking. Many patients with ALD may have little evidence of a severe AUD and may not require formal treatment. Structured brief interventions have been shown to be effective in a range of clinical settings, including for patients with liver disease, and may be repeated during long-term follow up107. Brief intervention does not require specialist skills and can be provided by any credible health care provider. An Indian study is exploring use of lay counsellors108 and if successful, will allow widespread dissemination of this intervention at lower cost. Many alcohol brief interventions have been made available online in recent years but are largely in the English language to date.

Treatment of ALD

Pharmacologic treatments for ALD are limited in efficacy, apart from corticosteroids for life-threatening AH109. The use and indications for corticosteroids in different geographic regions do not seem to differ. However, there is much interest in India in the use of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) in treatment of patients with acute on-chronic liver failure of which ALD is the predominant cause. Surprisingly, GCSF increased survival times, by a small amount, in patients with AH110. A larger randomized trial is underway in India to determine the efficacy of GCSF in the management of steriod non-responsive severe AH111.

Medicines to reduce relapse to heavy drinking are less widely used in the Asia than in Europe and the US. In China, treatment approaches differ from the West, because some drugs are not available, and involve use of traditional Chinese medicines and acupuncture112. Challenges to treatment in the West include limited access to treatment, stigma, and limited training of health care professionals112.

Liver transplantation for patients with ALD is accepted internationally; ALD has been a leading indication in Europe and the US and has been increasing in China113. Currently, 7.5% of all liver transplants go to patients with ALD47. Most liver transplants in the East come from living related donors114. In general, assessment principles are similar to those of Western countries47, 115. Survival times following transplantation seem to be similar in the East vs West116. However, a report from 38 Japanese centers found that mortality associated with recidivism was particularly high compared to reports from the West117.

Ethical concerns about liver transplantation in China have been raised and are progressively being addressed97. The overall system to provide adequate access to evidence-based care that integrates health problems is still evolving in many parts of the world. An integrated approach that combines medical care with psychosocial treatment for AUD is more effective at maintaining abstinence118. A study from Korea highlighted the difficulty in establishing this system of care for patients with AUD119. This may also be a challenge to implement broadly in Western nations.

Future Directions

There are worldwide differences in the prevalence of ALD, as well as in mortality, treatment, and the factors that contribute to development of ALD. It is undeniable that the ALD will continue to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. Global strategy and public policy to reduce harmful use of alcohol use and effective therapies for ALD are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study is partly supported by 1I01CX000361 from the Veterans Affairs Research and Administration, 5U01AA018389 from NIH/NIAAA and W81XWH-12-1-0497 from United States Department of Defense (to S.L)

LIST OF ABBREVIATION

- ADH

Alcohol dehydrogenase

- ALD

Alcoholic liver disease

- ALDH

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- AH

Alcoholic hepatitis

- AUD

Alcohol use disorder

- AUDIT

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- BMI

Body mass index

- DALYs

Disability-adjusted life years

- GCSF

granulocyte colony stimulating factor

- WHO

World Health Organization

Biographies

Suthat Liangpunsakul

Paul Haber

Geoff McCaughan

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS: NONE

Reference List

- 1.World Health Organization. Management of substance abuse. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/facts/alcohol/en/

- 2.Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2013;59:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, Bennett MK, James OF. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet. 1995;346:987–990. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieber CS, JONES DP, DECARLI LM. EFFECTS OF PROLONGED ETHANOL INTAKE: PRODUCTION OF FATTY LIVER DESPITE ADEQUATE DIETS. J Clin Invest. 1965;44:1009–1021. doi: 10.1172/JCI105200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chayanupatkul M, Liangpunsakul S. Alcoholic hepatitis: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6279–6286. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills SJ, Harrison SA. Comparison of the natural history of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:32–36. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutright P, Fernquist RM. Predictors of per capita alcohol consumption and gender-specific liver cirrhosis mortality rates: thirteen European countries, circa 1970–1984 and 1995–2007. Omega (Westport) 2010;62:269–283. doi: 10.2190/om.62.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramstedt M. Alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis mortality with and without mention of alcohol–the case of Canada. Addiction. 2003;98:1267–1276. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao W, Chen H, Su Z. China: alcohol today. Addiction. 2005;100:737–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sassi F. Tracking harmful alcohol use: Economics and Public Health Policy. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang YL, Xiang XJ, Wang XY, Cubells JF, Babor TF, Hao W. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: policy changes needed. B WORLD HEALTH ORGAN B WORLD HEALTH ORGAN. 2013;91:270–276. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global Information System on Alcohol and health (GISAH) Total alcohol per capita (15+ years) consumption, in liters of pure alcohol 2010. http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/gisah/consumption_total/atlas.html.

- 13.World Health Organization (WHO) Global status report on alcohol and health. 2014 http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/

- 14.Mathurin P, Bataller R. Trends in the management and burden of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S38–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathurin P. Is alcoholic hepatitis an indication for transplantation? Current management and outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:S21–S24. doi: 10.1002/lt.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zakhari S, Li TK. Determinants of alcohol use and abuse: Impact of quantity and frequency patterns on liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:2032–2039. doi: 10.1002/hep.22010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Health Service United Kingdom. Binge drinking. http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/alcohol/Pages/Bingedrinking.aspx.

- 18.World Health organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. Patterns of drinking score. http://www.who.int/gho/alcohol/consumption_patterns/drinking_score_patterns_text/en/

- 19.National Institute of Health/national Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Facts and Statistics. http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics.

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Preventioin. National Center for Health Statistics. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the National health Interview Survey. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease201506_09.pdf.

- 21.McAlaney J, McMahon J. Establishing rates of binge drinking in the UK: anomalies in the data. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:355–357. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z, Ding Z, Pang S, Li X, Zhang Y, Wang Z. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2009;373:2041–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachenmeier DW, Monakhova YB, Rehm J. Influence of unrecorded alcohol consumption on liver cirrhosis mortality. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7217–7222. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehm J, Kailasapillai S, Larsen E, Rehm MX, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD, Roerecke M, Lachenmeier DW. A systematic review of the epidemiology of unrecorded alcohol consumption and the chemical composition of unrecorded alcohol. Addiction. 2014;109:880–893. doi: 10.1111/add.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, Irving H, Baliunas D, Patra J, Roerecke M. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Torchio P. Meta-analysis of alcohol intake in relation to risk of liver cirrhosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:381–392. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellentani S, Saccoccio G, Costa G, Tiribelli C, Manenti F, Sodde M, Saveria CL, Sasso F, Pozzato G, Cristianini G, Brandi G. Drinking habits as cofactors of risk for alcohol induced liver damage. The Dionysos Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:845–850. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Askgaard G, Gronbaek M, Kjaer MS, Tjonneland A, Tolstrup JS. Alcohol drinking pattern and risk of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm J, Rehn N, Room R, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Jernigan D, Frick U. The global distribution of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9:147–156. doi: 10.1159/000072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li TK. Quantifying the risk for alcohol-use and alcohol-attributable health disorders: present findings and future research needs. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becker U, Gronbaek M, Johansen D, Sorensen TI. Lower risk for alcohol-induced cirrhosis in wine drinkers. Hepatology. 2002;35:868–875. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelletier S, Vaucher E, Aider R, Martin S, Perney P, Balmes JL, Nalpas B. Wine consumption is not associated with a decreased risk of alcoholic cirrhosis in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:618–621. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamper-Jorgensen M, Gronbaek M, Tolstrup J, Becker U. Alcohol and cirrhosis: dose–response or threshold effect? J Hepatol. 2004;41:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damgaard ST. Alcoholic hepatitis. Dan Med J. 2014;61:B4755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108–111. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jinjuvadia R, Liangpunsakul S. Trends in Alcoholic Hepatitis-related Hospitalizations, Financial Burden, and Mortality in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:506–511. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarin SK, Malhotra V, Nayyar A, Sundaram KR, Broor SL. Profile of alcoholic liver disease in an Indian hospital. A prospective analysis. Liver. 1988;8:132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1988.tb00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization Global health risks. Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf.

- 39.EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leon DA, McCambridge J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950 to 2002: an analysis of routine data. Lancet. 2006;367:52–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67924-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomson SJ, Westlake S, Rahman TM, Cowan ML, Majeed A, Maxwell JD, Kang JY. Chronic liver disease–an increasing problem: a study of hospital admission and mortality rates in England, 1979–2005, with particular reference to alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:416–422. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams R, Aspinall R, Bellis M, Camps-Walsh G, Cramp M, Dhawan A, Ferguson J, Forton D, Foster G, Gilmore I, Hickman M, Hudson M, Kelly D, Langford A, Lombard M, Longworth L, Martin N, Moriarty K, Newsome P, O’Grady J, Pryke R, Rutter H, Ryder S, Sheron N, Smith T. Addressing liver disease in the UK: a blueprint for attaining excellence in health care and reducing premature mortality from lifestyle issues of excess consumption of alcohol, obesity, and viral hepatitis. Lancet. 2014;384:1953–1997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61838-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheron N, Moore M, O’Brien W, Harris S, Roderick P. Feasibility of detection and intervention for alcohol-related liver disease in the community: the Alcohol and Liver Disease Detection study (ALDDeS) Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e698–e705. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X673711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Sorensen HT. Alcoholic cirrhosis in Denmark – population-based incidence, prevalence, and hospitalization rates between 1988 and 2005: a descriptive cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of discharges with chronic liver dsease and cirrhosis as the first-listed diagnosis. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/liver-disease.htm.

- 46.Fan JG. Epidemiology of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 1):11–17. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Ma L, Yin Q, Zhang X, Zhang C. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease and its association with socioeconomic status in north-eastern China. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1035–1041. doi: 10.1111/acer.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng SH, Li YM, Chen SH, Huang HX, Yuan GJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Are there any differences between China and Western countries in clinical features? Saudi Med J. 2014;35:753–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rattanamongkolgul S, Wongjitrat C, Puapankitcharoen P. Prevalence of cirrhosis registered in Nakhon Nayok, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(Suppl 2):S87–S91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phukan JP, Sinha A, Deka JP. Serum lipid profile in alcoholic cirrhosis: A study in a teaching hospital of north-eastern India. Niger Med J. 2013;54:5–9. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.108886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mann RE, Smart RG, Govoni R. The epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Research & Health. 2003;27:209–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terris M. Epidemiology of cirrhosis of the liver: national mortality data. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1967;57:2076–2088. doi: 10.2105/ajph.57.12.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blas E, Kurup AS. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44289/1/9789241563970_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cartwright AK, Shaw SJ, Spratley TA. The relationships between per capita consumption, drinking patterns and alcohol related problems in a population sample, 1965–1974 Part I: increased consumption and changes in drinking patterns. Br J Addict Alcohol Other Drugs. 1978;73:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1978.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh GK, Hoyert DL. Social epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis mortality in the United States, 1935–1997: trends and differentials by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and alcohol consumption. Hum Biol. 2000;72:801–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dufour MC. The critical dimension of ethnicity in liver cirrhosis mortality statistics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Joint effects of body weight and alcohol on elevated serum alanine aminotransferase in the United States population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1260–1268. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00743-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hart CL, Morrison DS, Batty GD, Mitchell RJ, Davey SG. Effect of body mass index and alcohol consumption on liver disease: analysis of data from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c1240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu XL, Luo JY, Tao M, Gen Y, Zhao P, Zhao HL, Zhang XD, Dong N. Risk factors for alcoholic liver disease in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2423–2426. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Couzigou P, Coutelle C, Fleury B, Iron A. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes, alcoholism and alcohol related disease. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1994;2:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yokoyama A, Mizukami T, Matsui T, Yokoyama T, Kimura M, Matsushita S, Higuchi S, Maruyama K. Genetic polymorphisms of alcohol dehydrogenase-1B and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 and liver cirrhosis, chronic calcific pancreatitis, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension among Japanese alcoholic men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1391–1401. doi: 10.1111/acer.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borras E, Coutelle C, Rosell A, Fernandez-Muixi F, Broch M, Crosas B, Hjelmqvist L, Lorenzo A, Gutierrez C, Santos M, Szczepanek M, Heilig M, Quattrocchi P, Farres J, Vidal F, Richart C, Mach T, Bogdal J, Jornvall H, Seitz HK, Couzigou P, Pares X. Genetic polymorphism of alcohol dehydrogenase in europeans: the ADH2*2 allele decreases the risk for alcoholism and is associated with ADH3*1. Hepatology. 2000;31:984–989. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.He L, Deng T, Luo HS. Genetic polymorphism in alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (ADH2) gene and alcoholic liver cirrhosis risk. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:7786–7793. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eng MY, Luczak SE, Wall TL. ALDH2, ADH1B, and ADH1C genotypes in Asians: a literature review. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:22–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hayashi S, Watanabe J, Kawajiri K. Genetic polymorphisms in the 5′-flanking region change transcriptional regulation of the human cytochrome P450IIE1 gene. J Biochem. 1991;110:559–565. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watanabe J, Hayashi S, Kawajiri K. Different regulation and expression of the human CYP2E1 gene due to the RsaI polymorphism in the 5′-flanking region. J Biochem. 1994;116:321–326. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grove J, Brown AS, Daly AK, Bassendine MF, James OF, Day CP. The RsaI polymorphism of CYP2E1 and susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease in Caucasians: effect on age of presentation and dependence on alcohol dehydrogenase genotype. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:335–342. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong NA, Rae F, Simpson KJ, Murray GD, Harrison DJ. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome p4502E1 and susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in a white population: a study and literature review, including meta-analysis. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:88–93. doi: 10.1136/mp.53.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Okamoto K, Murawaki Y, Yuasa I, Kawasaki H. Effect of ALDH2 and CYP2E1 gene polymorphisms on drinking behavior and alcoholic liver disease in Japanese male workers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:19S–23S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200106001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee HC, Lee HS, Jung SH, Yi SY, Jung HK, Yoon JH, Kim CY. Association between polymorphisms of ethanol-metabolizing enzymes and susceptibility to alcoholic cirrhosis in a Korean male population. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:745–750. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu Y, Zhou LY, Meng XW. Genetic polymorphism of two enzymes with alcoholic liver disease in Northeast China. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:204–207. doi: 10.5754/hge10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sozio MS, Liangpunsakul S, Crabb D. The role of lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of alcoholic and nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:378–390. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kitchens RL. Role of CD14 in cellular recognition of bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Chem Immunol. 2000;74:61–82. doi: 10.1159/000058750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tapping RI, Tobias PS. Soluble CD14-mediated cellular responses to lipopolysaccharide. Chem Immunol. 2000;74:108–121. doi: 10.1159/000058751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baldini M, Lohman IC, Halonen M, Erickson RP, Holt PG, Martinez FD. A Polymorphism* in the 5′ flanking region of the CD14 gene is associated with circulating soluble CD14 levels and with total serum immunoglobulin E. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:976–983. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jarvelainen HA, Orpana A, Perola M, Savolainen VT, Karhunen PJ, Lindros KO. Promoter polymorphism of the CD14 endotoxin receptor gene as a risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:1148–1153. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chao YC, Chu HC, Chang WK, Huang HH, Hsieh TY. CD14 promoter polymorphism in Chinese alcoholic patients with cirrhosis of liver and acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6043–6048. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grove J, Daly AK, Bassendine MF, Gilvarry E, Day CP. Interleukin 10 promoter region polymorphisms and susceptibility to advanced alcoholic liver disease. Gut. 2000;46:540–545. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Auguet T, Vidal F, Broch M, Olona M, Aguilar C, Morancho B, Lopez-Dupla M, Quer JC, Sirvent JJ, Richart C. Polymorphisms in the interleukin-10 gene promoter and the risk of alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease in Caucasian Spaniard men. Alcohol. 2010;44:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richardet JP, Scherman E, Costa C, Campillo B, Bories PN. Combined polymorphisms of tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-10 genes in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:673–679. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roy N, Mukhopadhyay I, Das K, Pandit P, Majumder PP, Santra A, Datta S, Banerjee S, Chowdhury A. Genetic variants of TNFalpha, IL10, IL1beta, CTLA4 and TGFbeta1 modulate the indices of alcohol-induced liver injury in East Indian population. Gene. 2012;509:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang AM, Wen LL, Yang CS, Wang SC, Chen CS, Bair MJ. Interleukin 10 promoter haplotype is associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis in Taiwanese patients. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2014;30:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. PNPLA3, the triacylglycerol synthesis/hydrolysis/storage dilemma, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6018–6026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tian C, Stokowski RP, Kershenobich D, Ballinger DG, Hinds DA. Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stickel F, Buch S, Lau K, Meyer zu SH, Berg T, Ridinger M, Rietschel M, Schafmayer C, Braun F, Hinrichsen H, Gunther R, Arlt A, Seeger M, Muller S, Seitz HK, Soyka M, Lerch M, Lammert F, Sarrazin C, Kubitz R, Haussinger D, Hellerbrand C, Broring D, Schreiber S, Kiefer F, Spanagel R, Mann K, Datz C, Krawczak M, Wodarz N, Volzke H, Hampe J. Genetic variation in the PNPLA3 gene is associated with alcoholic liver injury in caucasians. Hepatology. 2011;53:86–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.24017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Buch S, Stickel F, Trepo E, Way M, Herrmann A, Nischalke HD, Brosch M, Rosendahl J, Berg T, Ridinger M, Rietschel M, McQuillin A, Frank J, Kiefer F, Schreiber S, Lieb W, Soyka M, Semmo N, Aigner E, Datz C, Schmelz R, Bruckner S, Zeissig S, Stephan AM, Wodarz N, Deviere J, Clumeck N, Sarrazin C, Lammert F, Gustot T, Deltenre P, Volzke H, Lerch MM, Mayerle J, Eyer F, Schafmayer C, Cichon S, Nothen MM, Nothnagel M, Ellinghaus D, Huse K, Franke A, Zopf S, Hellerbrand C, Moreno C, Franchimont D, Morgan MY, Hampe J. A genome-wide association study confirms PNPLA3 and identifies TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 as risk loci for alcohol-related cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1443–1448. doi: 10.1038/ng.3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chamorro AJ, Torres JL, Miron-Canelo JA, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R, Laso FJ, Marcos M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the I148M variant of patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) is significantly associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:571–581. doi: 10.1111/apt.12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang Y, Cai W, Song J, Miao L, Zhang B, Xu Q, Zhang L, Yao H. Association between the PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Uygur and Han ethnic groups of northwestern China. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee SS, Byoun YS, Jeong SH, Woo BH, Jang ES, Kim JW, Kim HY. Role of the PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fibrosis in Korea. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2967–2974. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dutta AK. Genetic factors affecting susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease in an Indian population. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:901–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Altamirano J, Miquel R, Katoonizadeh A, Abraldes JG, Duarte-Rojo A, Louvet A, Augustin S, Mookerjee RP, Michelena J, Smyrk TC, Buob D, Leteurtre E, Rincon D, Ruiz P, Garcia-Pagan JC, Guerrero-Marquez C, Jones PD, Barritt AS, Arroyo V, Bruguera M, Banares R, Gines P, Caballeria J, Roskams T, Nevens F, Jalan R, Mathurin P, Shah VH, Bataller R. A histologic scoring system for prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1231–1239. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.World Health Organization. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/alcstratenglishfinal.pdf?ua=1.

- 95.Cook WK, Bond J, Greenfield TK. Are alcohol policies associated with alcohol consumption in low- and middle-income countries? Addiction. 2014;109:1081–1090. doi: 10.1111/add.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zaridze D, Brennan P, Boreham J, Boroda A, Karpov R, Lazarev A, Konobeevskaya I, Igitov V, Terechova T, Boffetta P, Peto R. Alcohol and cause-specific mortality in Russia: a retrospective case-control study of 48,557 adult deaths. Lancet. 2009;373:2201–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/hep.27406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Esser MB, Jernigan DH. Multinational Alcohol Market Development and Public Health: Diageo in India. Am J Public Health. 2015:e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jiang H, Room R, Hao W. Alcohol and related health issues in China: action needed. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e190–e191. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li Q, Babor TF, Zeigler D, Xuan Z, Morisky D, Hovell MF, Nelson TF, Shen W, Li B. Health promotion interventions and policies addressing excessive alcohol use: a systematic review of national and global evidence as a guide to health-care reform in China. Addiction. 2015;110(Suppl 1):68–78. doi: 10.1111/add.12784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lin CM, Liao CM. Inpatient expenditures on alcohol-attributed diseases and alcohol tax policy: a nationwide analysis in Taiwan from 1996 to 2010. PUBLIC HEALTH PUBLIC HEALTH. 2014;128:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nelson TF, Xuan Z, Blanchette JG, Heeren TC, Naimi TS. Patterns of change in implementation of state alcohol control policies in the United States, 1999–2011. Addiction. 2015;110:59–68. doi: 10.1111/add.12706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kumar SG, P KC, S L, S E, Vinayagamoorthy, Kumar V. Prevalence and Pattern of Alcohol Consumption using Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in Rural Tamil Nadu, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1637–1639. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5521.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nayak MB, Bond JC, Cherpitel C, Patel V, Greenfield TK. Detecting alcohol-related problems in developing countries: a comparison of 2 screening measures in India. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li Q, Babor TF, Hao W, Chen X. The Chinese translations of Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in China: a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:416–423. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim SS, Gulick EE, Nam KA, Kim SH. Psychometric properties of the alcohol use disorders identification test: a Korean version. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Greenfield SF, Shields A, Connery HS, Livchits V, Yanov SA, Lastimoso CS, Strelis AK, Mishustin SP, Fitzmaurice G, Mathew TA, Shin S. Integrated Management of Physician-delivered Alcohol Care for Tuberculosis Patients: Design and Implementation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nadkarni A, Velleman R, Dabholkar H, Shinde S, Bhat B, McCambridge J, Murthy P, Wilson T, Weobong B, Patel V. The systematic development and pilot randomized evaluation of counselling for alcohol problems, a lay counselor-delivered psychological treatment for harmful drinking in primary care in India: the PREMIUM study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:522–531. doi: 10.1111/acer.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vuittonet CL, Halse M, Leggio L, Fricchione SB, Brickley M, Haass-Koffler CL, Tavares T, Swift RM, Kenna GA. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:1265–1276. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Singh V, Sharma AK, Narasimhan RL, Bhalla A, Sharma N, Sharma R. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1417–1423. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Efficacy of G-CSF in the management of steriod non-responsive severe alcoholic hepatitis. 2015.

- 112.Tang YL, Hao W, Leggio L. Treatments for alcohol-related disorders in China: a developing story. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47:563–570. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang FK, Zhang JY, Jia JD. Treatment of patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shukla A, Vadeyar H, Rela M, Shah S. Liver Transplantation: East versus West. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Varma V, Mehta N, Kumaran V, Nundy S. Indications and contraindications for liver transplantation. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:121862. doi: 10.4061/2011/121862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen GH, Yang Y, Lu MQ, Cai CJ, Zhang Q, Zhang YC, Xu C, Li H, Wang GS, Yi SH, Zhang J, Zhang JF, Yi HM. Liver transplantation for end-stage alcoholic liver disease: a single-center experience from mainland China. Alcohol. 2010;44:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Egawa H, Nishimura K, Teramukai S, Yamamoto M, Umeshita K, Furukawa H, Uemoto S. Risk factors for alcohol relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis in Japan. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:298–310. doi: 10.1002/lt.23797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, Kayani WT, Bano S, Lindsay J, El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Efficacy of Psychosocial Interventions in Inducing and Maintaining Alcohol Abstinence in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease – A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kim JW, Lee BC, Kang TC, Choi IG. The current situation of treatment systems for alcoholism in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:181–189. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]