Abstract

Cell migration plays crucial roles during development. An excellent model to study coordinated cell movements is provided by the migration of border cell clusters within a developing Drosophila egg chamber. In a mutagenesis screen, we isolated two alleles of the gene rickets (rk) encoding a G-protein-coupled receptor. The rk alleles result in border cell migration defects in a significant fraction of egg chambers. In rk mutants, border cells are properly specified and express the marker Slbo. Yet, analysis of both fixed as well as live samples revealed that some single border cells lag behind the main border cell cluster during migration, or, in other cases, the entire border cell cluster can remain tethered to the anterior epithelium as it migrates. These defects are observed significantly more often in mosaic border cell clusters, than in full mutant clusters. Reduction of the Rk ligand, Bursicon, in the border cell cluster also resulted in migration defects, strongly suggesting that Rk signaling is utilized for communication within the border cell cluster itself. The mutant border cells show defects in localization of the adhesion protein E-cadherin, and apical polarity proteins during migration. E-cadherin mislocalization occurs in mosaic clusters, but not in full mutant clusters, correlating well with the rk border cell migration phenotype. Our work has identified a receptor with a previously unknown role in border cell migration that appears to regulate detachment and polarity of the border cell cluster coordinating processes within the cells of the cluster themselves.

Keywords: Rickets, cell migration, Drosophila, border cells, adhesion, polarity

Introduction

Collective cell migration is an important mechanism employed in critical developmental processes, including vertebrate neural crest migration (reviewed in Gammill and Bronner-Fraser, 2003; Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2008) and the wound healing response (reviewed in Valluru et al., 2011). Misregulation of cell motility is also associated with human disease such as heart malformation and cancer metastasis (reviewed in Balzer and Konstantopoulos, 2011; Castano et al., 2011; Savagner, 2010). Here, we focus on border cell migration during Drosophila oogenesis, a well-established model system to study regulation of collective cellular migration (Montell, 2003; Montell et al., 2012; Rorth, 2002).

Border cell migration occurs during Stage 9 of oogenesis. At this stage, the Drosophila egg chamber consists of 16 germline cells – the oocyte and 15 nurse cells – surrounded by a monolayer of somatically derived follicle epithelial cells (Spradling, 1993). The border cells initiate from within this somatic epithelium at the anterior of the egg chamber (Montell et al., 1992). Two specialized polar cells located within the epithelium at the anterior tip of the egg chamber secrete the ligand Unpaired (Upd), which activates the JAK/STAT pathway in neighboring epithelial cells (Ghiglione et al., 2002; Silver and Montell, 2001). This results in expression of the border cell specification marker Slow border cells (Slbo) and subsequent formation of the outer border cells (Silver and Montell, 2001). Once the border cell cluster is formed, its migration is then guided from the anterior epithelium posteriorly to the border between the oocyte and the nurse cells by guidance cues released from the oocyte (Duchek and Rorth, 2001; Duchek et al., 2001; McDonald et al., 2003). Border cell migration is typically complete by Stage 10 of oogenesis, and the biological function of the border cells once they complete their migration is to contribute to formation of the micropyle (Montell et al., 1992).

In order for the border cells to properly detach from the follicular epithelium, polarity and adhesion of the border cell cluster must be tightly regulated. While the border cells are still within the epithelium, they exhibit typical epithelial polarity with apical markers such as Bazooka (Baz) and Par-6 on the apical side, and lateral markers such as Par-1 present basolaterally. The border cells undergo a shift in polarity when they detach and migrate. Disruption of apical polarity proteins interferes with the ability of the border cell cluster to migrate appropriately (McDonald et al., 2008; Pinheiro and Montell, 2004). Polarity proteins including Par-6 and Baz are imperative for the proper localization of the adhesion proteins E-cadherin and beta-Integrin (Pinheiro and Montell, 2004). E-cadherin allows border cells to remain together as a cluster, and E-cadherin and Integrin together provide traction to migrate across the nurse cells (Fox et al., 1999; Llense and Martin-Blanco, 2008; Niewiadomska et al., 1999).

Rickets (Rk) is a G-protein-coupled receptor that is known to play a role in Drosophila cuticle tanning and wing expansion (Baker and Truman, 2002; Natzle et al., 2008). Prior to expansion, the Drosophila wing consists of a sheet of epithelial cells. These cells undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and migrate out of the wing, allowing the wing membrane to unfold and flatten (Kiger et al., 2007; Natzle et al., 2008). Rk, and its heterodimeric ligand Bursicon consisting of Bursicon alpha (Burs alpha) and Partner of Bursicon (Pburs) (Baker and Truman, 2002; Dewey et al., 2004; Mendive et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2005), are important for EMT exhibited by the epithelial cells within the initially folded wing (Natzle et al., 2008), although its precise downstream effects have not been fully elucidated.

Here, we show a novel role for the G-protein-coupled receptor, Rickets (Rk), in border cell migration. We find that Rk is important for allowing the border cells to properly organize their polarity during migration. When Rk activity in the border cells is compromised, the adhesion protein E-cadherin, and apical polarity markers such as atypical Protein Kinase C (aPKC) and Par-6 become mislocalized within the border cells. In addition, individual cells often lag behind the main migrating border cell cluster, and in some cases, remain tethered to the anterior epithelium. Interestingly, we find that mosaic border cell clusters exhibit more significant migration defects than border cell clusters in which all of the cells are mutant. These findings demonstrate that a G-protein-coupled receptor previously implicated in an EMT-like process in the wing can also regulate collective cell movement in oogenesis. This receptor appears to be involved in intercellular communication, resulting in correct E-cadherin and polarity protein distribution among a group of migrating cells.

Materials and Methods

Fly Strains and Genetics

The rkJL78 and rkKB61 alleles were generated in an EMS mutagenesis screen performed on chromosome 2L. This screen utilized mosaic egg chambers and sought to identify genes affecting general ovarian follicle cell development, similarly to the screen performed on the X chromosome (Denef et al., 2008). The rkJL78 allele was sequenced and found to contain a small deletion affecting the 4th intron and 5th exon of the rk gene. The rkw11p allele (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) was recombined onto an FRT40A chromosome. Mosaic egg chambers containing homozygous rk mutant border cells were generated with the FRT/UAS-Flp/Gal4 system (Duffy et al., 1998), using y w hsflp; ubi-GFP FRT40A flies and heat shocking larvae and pupae at 37 °C for 1 hr, 2–3 times. rk RNAi (Vienna Drosophila Resource Center, VDRC; line v29931) was driven by upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 drivers in the upd-Gal4 ; slbo-Gal4, UAS-GFP / CyO line (gift from S. Noselli). For live imaging experiments, rk RNAi was driven with the slbo-Gal4 driver. A line expressing rk-Gal4 consisting of a T2A-Gal4 in frame fusion with the rk coding sequence was obtained from B. H. White (Diao and White, 2012). Bursicon alpha allele burs alphaZ5569 was a gift from J. Kiger. RNAi against burs alpha was induced by the JF02260 line from the TRiP collection, which has been used in the field as a tool to study burs alpha (Loveall and Dietcher, 2010) and has only one predicted amplicon with no off-target effects as per the TRiP web page. RNAi against Par-6 and aPKC was induced by lines HMS01410 and GL00007 respectively, from the TRiP collection. These lines as well as FRT and Flp lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Complementation Tests

Complementation tests with rk alleles rk1, rk4, and rkw11p confirmed that rk was the affected gene in the line JL78 from our screen. We also performed complementation tests with the KB61 line and either JL78 or one of the deficiency lines Df(2L)BSC252 and Df(2L)ED793. Both JL78 and KB61 yield some homozygous escapers in trans to deficiencies that delete rk, as well as in trans to each other. Those escapers show the folded wing phenotype originally described for rk mutants (Baker and Truman, 2002). The rk1 and rk4 alleles as well as deficiency lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Immunofluorescence

Ovaries were dissected in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and kept on ice before being fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes. Standard staining procedures were then utilized according to Ashburner (1989). Primary antibodies used were rat anti-Slbo (1:500, gift from P. Rorth) (Borghese et al., 2006), rabbit anti-Baz (1:500, gift from J. Zallen), rabbit anti-Par-6 (1:500, gift from D. J. Montell) (Pinheiro & Montell, 2004), rabbit anti-aPKC (1:1000, DSHB), rabbit anti-GFP (1:500, Millipore), mouse anti-Sn (1:20, DSHB) and rat anti-DECadherin (1:20, DSHB, DCAD2). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to AlexaFluor568 (1:1000, Molecular Probes). Phalloidin conjugates and Hoechst were from Molecular Probes and used at 1:1000, with the exception of Phalloidin conjugated to AlexaFluor 647 which was used at 1:100. Images were taken with a Nikon A1 confocal microscope, a Nikon A1-RS spectral confocal microscope, and a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Live Imaging

Border cell migration was observed in egg chambers expressing rk RNAi (VDRC, line v29931) driven by slbo-Gal4. Cell membranes were visualized with a Gap43-mCherry marker (Martin et al., 2010), which labels the membranes of all cells, with especially strong signal surrounding the polar cells. Females were fed yeast for 40 h prior to dissection. Individual ovarioles were dissected out of the ovary, and the germaria and older egg chambers were removed from these ovarioles. Dissection was performed in media previously described (Prasad et al., 2007; Domanitskaya et al., 2014). Droplets of media containing dissected ovarioles were imaged with a Nikon Ti-E spinning disc confocal microscope equipped with a Perfect Focus System, a Yokogawa spinning disc, and a Hamamatsu detector. We imaged border cell cluster detachment and early migration for approximately 4–6 h in rk RNAi expressing egg chambers, and wild type egg chambers expressing the Gap43-mCherry membrane marker as a control. A 561 nm laser was utilized to detect the mCherry signal. 10–20 μm Z stacks were imaged to capture the whole border cell cluster, with Z stacks containing 1 μm steps taken every 3 min.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of differences between mutant and control phenotypes such as migration distance, detachment phenotype, and protein localization were determined with Chi square tests for goodness of fit, or for independence, as indicated for each figure. Asterisks indicate p-values: * indicates a p-value less than 0.05, ** indicates a p-value less than 0.01, and *** indicates a p-value less than 0.001. Differences that are not significant are indicated with n.s.

Results

Border cell migration is delayed in egg chambers containing rickets mutant border cells

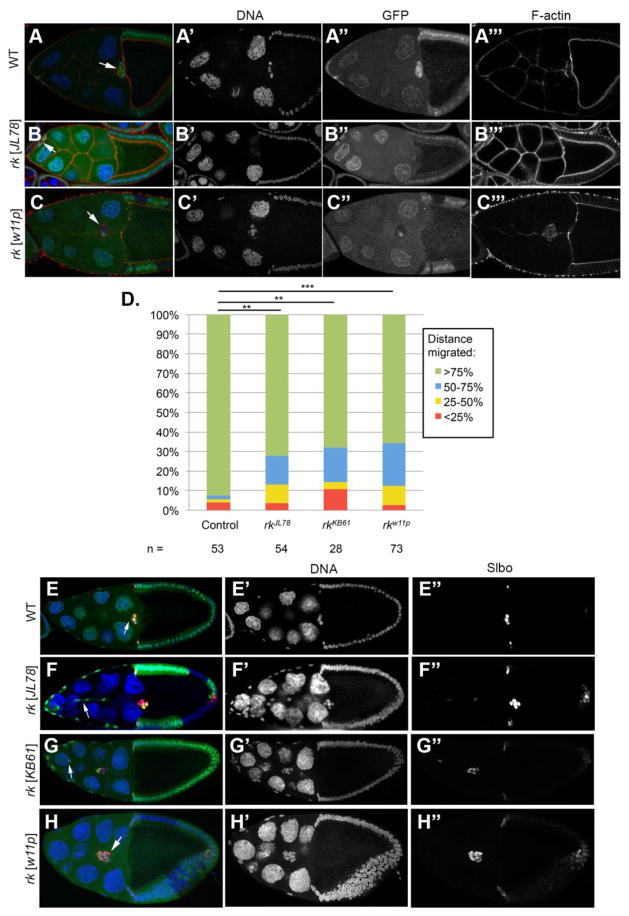

Two mutant lines, JL78 and KB61, were generated in an EMS mutagenesis screen performed on chromosome 2L in our laboratory, using mosaics to isolate mutants that exhibit follicle cell morphogenesis defects. The lines JL78 and KB61 contain mutations that caused defects in border cell migration. Complementation tests showed that they are alleles of rickets (rk), a G-protein-coupled receptor (Baker and Truman, 2002; Eriksen et al., 2000). We subsequently analyzed both lines as well as a known strong allele, rkw11p (Baker and Truman, 2002; Eriksen et al., 2000) for border cell phenotypes in mosaic animals (Fig. 1). We quantified the frequency with which mutant border cell clusters migrated various percentages of the normal migration distance in Stage 10 egg chambers (Fig. 1D). In wild-type controls, the majority of border cells complete migration to the border between the oocyte and the nurse cells by Stage 10 of oogenesis (Fig. 1D). When the border cell clusters contain rkJL78, rkKB61, or rkw11p mutant border cells, a significant fraction of the clusters exhibit migration delay (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Border cell migration phenotype of rk mutants expressing Slbo marker.

(A–C) Stage 10 egg chambers. Mutant cells lack nuclear GFP (green), and phalloidin staining indicates F actin (red). Hoechst staining (blue) marks nuclei. Anterior is to the left. (A) A wildtype egg chamber, with an arrow indicating border cells. (B) An egg chamber with rkJL78 or (C) rkw11p mutant border cells. Arrows indicate mutant border cells lacking GFP. (D) Quantification of migration distance in Stage 10 egg chambers with rk mutant border cells. Frequency of migration to quadrants of the normal migration distance is scored in border cell clusters containing mutant border cells. Statistical significance was determined with a Chi square goodness of fit test. (E–H) Egg chambers at Stage 10, with mutant cells lacking GFP fluorescence. Cell nuclei are marked with Hoechst (blue), and Slbo staining indicates the border cells (red). rk mutant border cells express the border cell specification marker Slbo (E) Control border cell clones completely detach and migrate to the nurse cell-oocyte border (arrow). (F–G) Border cell clusters containing rk mutant clones exhibit detachment defects including (F) tethers to the anterior epithelium (arrow), and (G) border cells left behind the main cluster (arrow).

In order to distinguish whether the defects in border cell migration were a result of failure to specify the border cells, or failure of the border cells to exhibit migration behavior, we immunostained egg chambers with antibodies against the border cell specification marker Slow border cells (Slbo). Slbo is expressed in the border cells once they have been specified by JAK/STAT signaling from the anterior polar cells (Montell et al., 1992; Silver and Montell, 2001; Silver et al., 2005). In all cases examined, rkJL78, rkKB61, and rkwp11 mutant border cells express border cell specification markers, indicating that mutant border cells are still specified properly (Fig. 1F–H). In addition, we did not observe any supernumerary border cells, as we always counted a total of 7–10 border cells (Fig. 1). These observations suggest that rk mutations do not affect the specification and formation of the initial border cell cluster. The border cell migration phenotype in these mutants is therefore a result of defective cell behavior during the migration process.

Border cells lag behind the main border cell cluster when the cluster contains rk mutant cells

Given the reported function of Rk signaling in the wing, where it is facilitating an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Kiger et al., 2007; Natzle et al., 2008), we closely examined the behavior of delayed border cell clusters in mosaic egg chambers containing rkJL78, rkKB61, or rkw11p mutant cells. Visualizing the border cells and their protrusions revealed that neighboring follicular epithelial cells and border cells sometimes remain partially connected and mutant border cells often “trail” behind the main border cell cluster (Fig. 1F, G). This phenotype indicates a defect in the EMT-like transition that is characteristic of wild type border cells, which fully detach from the epithelium. These results also indicate that major defects in the rk mutants occur already at the initial stages of the migration process when the cells should rapidly detach from their epithelial neighbors.

Defective detachment of border cells from the epithelium during migration is observed using live imaging techniques

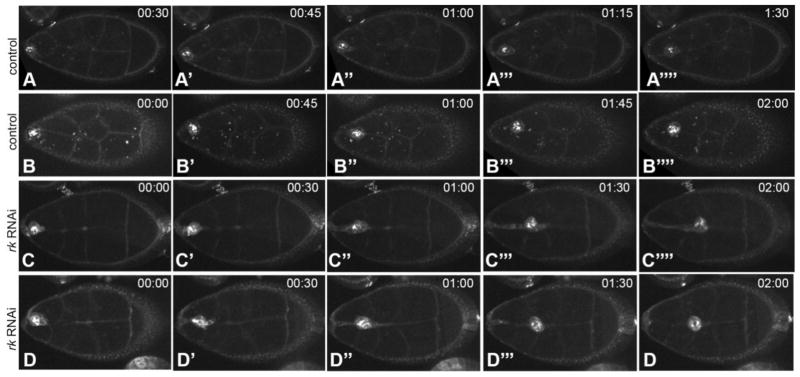

We utilized live imaging techniques (Prasad et al., 2007) to further characterize the behavior of border cells with compromised rk expression. Egg chambers expressing rk RNAi in the border cells using slbo-Gal4 were observed during detachment. A fluorescently tagged membrane marker was utilized to visualize the border cells. In 86% of the mutant egg chambers imaged (n = 7), border cells within the cluster remained tethered to the anterior epithelium during the initial migration attempts. This tethering was not observed in slbo-Gal4 control egg chambers (n = 14) (Fig. 2A, B and Movies S1 and S2). At the same time, protrusions made by mutant border cells were always emanating from leader cells at the front of the cluster towards the oocyte, as is typical of wild type clusters (86% of control egg chambers (n = 14) in our sample).

Figure 2. Live imaging describes the tethering phenotype of rk mutants.

(A–D) Border cell migration imaged in live egg chambers. Membranes are marked with a Gap-43 membrane Cherry marker (white). Time elapsed is indicated in the upper right-hand corner of each frame. Egg chambers are oriented with anterior to the left. (A–B) gap-43-cherry control egg chambers imaged during the process of detachment of the border cell cluster. (C–D) rk RNAi-expressing egg chambers in which the border cells maintain a tether to the epithelium as they migrate. (D) The tether breaks during migration.

In some cases (n = 4) the mutant border cells failed to leave the anterior-most region of the egg chamber. The border cells extended forward protrusions, but at least two cells remained attached to the epithelium. In these instances, the border cells retracted their forward protrusions, and the cluster itself appeared to be pulled backwards towards the epithelium (Movie S3). In other cases (n = 2) the rk RNAi expressing border cells were able to migrate posteriorly, but the border cell cluster remained tethered to the anterior during migration (Fig. 2C, D and Movie S4, 5). In both scenarios, the rearmost cell in the cluster appeared to be stretched such that one end was attached to the border cell cluster and the other end was attached to the epithelium. The main border cell cluster migrated more than 50% of the normal distance during the time that the movie was taken, which includes the first few hours of border cell migration. During movement, the rear “tether” to the epithelium continued to stretch to allow movement of the main cluster. In one of these egg chambers, the tether eventually broke, and two cells that constituted part of the tether were released in a retracting movement that allowed these cells to rejoin the other epithelial cells at the anterior while the rest of the cluster migrated posteriorly (Fig. 2D, and Movie S5).

The live imaging experiments clearly demonstrate consistent detachment defects in the affected border cells. In 86% of cases, the border cells adhered to epithelial cells during the time when the two cell types normally separate from one another, as compared with 0% of the control egg chambers that we imaged live (n = 14). The data from fixed Stage 10 rk RNAi egg chambers indicated that the border cell migration defect was observed less often. This is likely due to the later events in migration: eventually >50% of clusters from Stage 10 egg chambers manage to complete migration (n = 56, Fig. 3E). We attribute the lower frequency of defects observed in the older fixed Stage 10 egg chambers to the fact that the tether connecting mutant border cells to the anterior of the egg chamber sometimes breaks during Stage 9, allowing mutant border cell clusters to complete migration. Our live imaging suggests that Stage 10 egg chambers in which the border cells had completed their migration might initially have had an anterior tether that could only be observed in our live imaging of detachment, and would not be captured in fixed images at Stage 10. It is striking that in 6 out of 7 cases, the rear end cells clearly showed severe problems in detaching from the epithelium, while the cells in a cluster at the front were moving forward, a phenotype that, to our knowledge, has not been previously described with such high penetrance in a mutant situation.

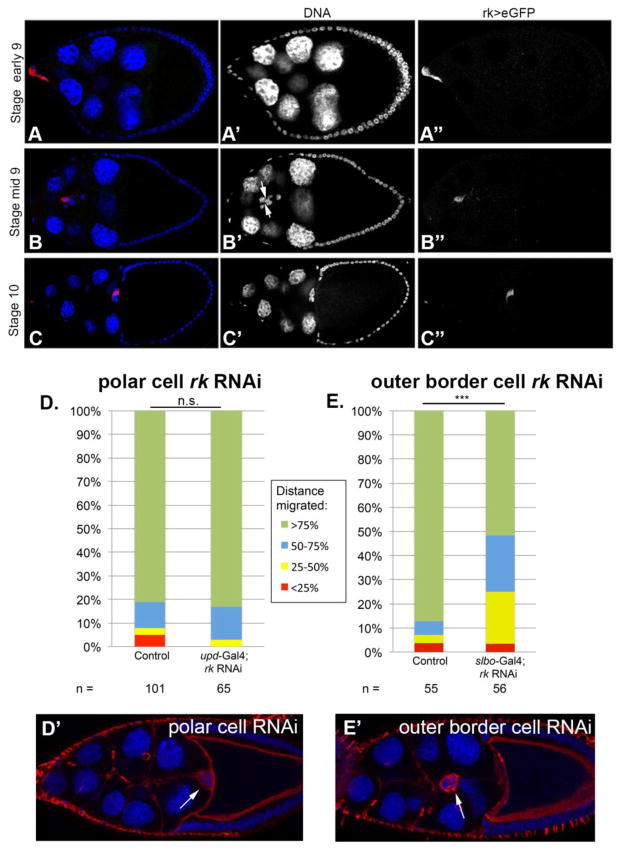

Figure 3. rk is expressed in the ovary and is required in the outer border cells.

(A–C) rk expression is visualized in the border cells of egg chambers using UAS-eGFP driven by rk-Gal4. Egg chambers are oriented with anterior to the left, and stained with an antibody against GFP (red). rk > GFP exhibits patchy expression, but this is due to the Gal4/UAS system which is known to express in this manner (Skora and Spradling, 2010; Hudson and Cooley, 2014). Cell nuclei are marked with Hoechst (blue). rk expression is depicted (A) before, (B) during, and (C) after migration of the border cells. (B′) Arrows indicate the two polar cells at the center of the border cell cluster. (D–E) Quantification of border cell migration distance in Stage 10 egg chambers when rk RNAi is expressed in (D) the polar cells only or (E) the outer border cells only. Statistical significance was determined with a Chi square goodness of fit test. (D′) A Stage 10 egg chamber with rk RNAi expressed in polar cells alone. DNA is labeled with Hoechst in blue, and F-actin is labeled with phalloidin in red. Arrow indicates the border cell cluster. (E′) A Stage 10 egg chamber with rk RNAi expressed in outer border cells alone. DNA is labeled with Hoechst in blue, and F-actin is labeled with phalloidin in red. Arrow indicates the delayed border cell cluster.

Expression of Rk as well as Bursicon is required in the border cells for proper migration behavior

The Rk receptor is known to bind a heterodimeric ligand in the wing: Bursicon, which is comprised of two subunits, Bursicon alpha (Burs alpha) and Partner of bursicon (Pburs). When either of the subunits is mutant, the ligand is no longer functional (Baker and Truman, 2002; Dewey et al., 2004; Mendive et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2005). We found that the Rk receptor is expressed in the Drosophila ovary. Specifically, we utilized GFP antibody staining of ovaries expressing rk-Gal4; UAS-eGFP (Diao and White, 2012), to observe rk expression. GFP expression levels were variable throughout the cluster, but clearly revealed that rk is expressed in border cells (Fig. 3A–C). The border cell cluster is comprised of two central polar cells, surrounded by migratory outer border cells. The polar cells can be clearly distinguished from the outer border cells because of their morphology, their nuclear spacing, and their position directly in the center of the border cell cluster rosette (Fig. 3B′). We tested whether rk is important in all of the border cells, or just in the outer migratory border cells that carry the two inner, non-motile polar cells. To accomplish this, we utilized rk RNAi expressed either in the outer border cells only with a slbo-Gal4 driver, or in the inner polar cells only with an upd-Gal4 driver. These RNAi experiments suggest that only rk expressed in the outer border cells is important for the migration of the border cells (Fig. 3D, E).

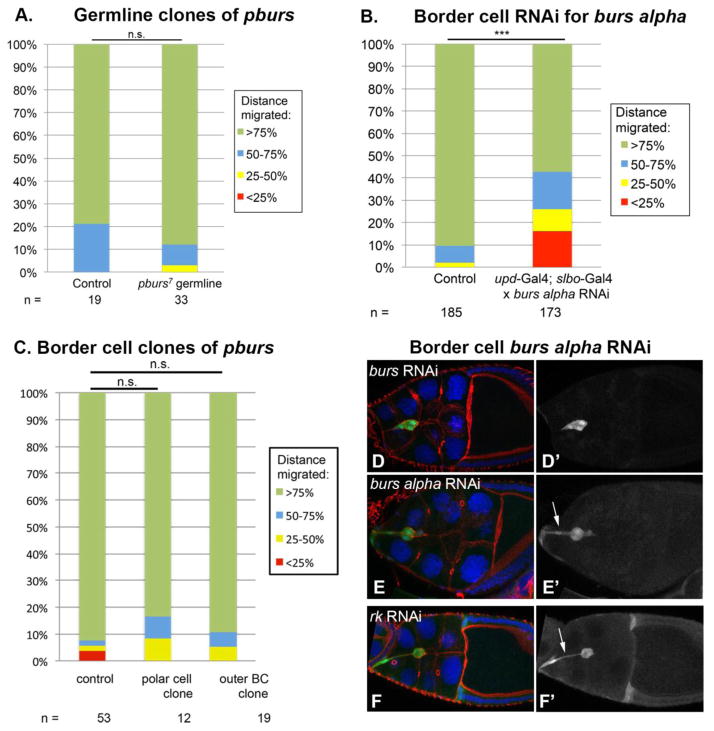

Our analysis demonstrating the expression of the Rk receptor within the border cell cluster leads to the question of where the Rk ligand, Bursicon, is present. Bursicon is important for border cell migration; burs alphaZ5569 homozygotes reared at temperatures between 26.5 and 29 degrees C exhibit a significant delay in migration compared with wild type controls (n = 30, p < 0.01). Both the Burs alpha and Pburs subunits of the Bursicon ligand are required to signal to the Rk receptor (Luo et al., 2005; Mendive et al., 2005). In order to determine whether Bursicon ligand emanating from the oocyte was important for border cell migration, we wanted to compromise expression of one of the components of the Bursicon ligand in the germline. The available burs alpha or pburs RNAi lines do not function in the germline, therefore we examined the requirement for Bursicon in the germline by generating germline clones of pburs7. Egg chambers containing full mutant germline clones of pburs7, which encodes one component of the Bursicon heterodimer, did not exhibit a border cell migration delay, indicating that any Bursicon that might be expressed in germline cells, such as the oocyte, does not influence border cell motility (Fig. 4A). In contrast, RNAi against burs alpha, encoding the other component of the Bursicon heterodimer, driven by a combination of upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 in all border cells resulted in a significant border cell migration delay (Fig. 4B, D). These results indicate that Bursicon expressed within the border cells themselves is important for Rk signaling during border cell migration, and suggest that this ligand is not a directional attractant during migration.

Figure 4. Burs is required in the border cells.

(A) Quantification of border cell migration distance at Stage 10 in control FRT40A (wild-type) full germline clones and in pburs7 full germline clones. (B) Quantification of border cell migration distance at Stage 10 when burs alpha RNAi is expressed in all border cells relative to controls. A significant migration delay is observed when burs alpha RNAi is expressed in the border cells, determined by a Chi square goodness of fit test. (C) Quantification of border cell migration at Stage 10 when only either polar cells or outer border cells are mutant for pburs7. (D–E) burs RNAi is expressed in the border cells with upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Hoechst labels DNA in blue, phalloidin labels F-actin in red, and UAS-eGFP labels the border cells where RNAi is expressed. Anterior is to the left. (D′) upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 driven UAS-eGFP in Stage 10 border cells expressing burs RNAi. (E′) upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 driven UAS-eGFP in Stage 9 border cells expressing burs RNAi. Arrow indicates a tether to the anterior of the egg chamber. (F) rk RNAi is expressed in the border cells with upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Hoechst labels DNA in blue, phalloidin labels F-actin in red, and UAS-eGFP labels the border cells where RNAi is expressed. Anterior is to the left. (F′) upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 driven UAS-eGFP in Stage 10 border cells expressing rk RNAi. Arrow indicates a tether to the anterior of the egg chamber.

The non-motile polar cells, which are located at the center of the border cell cluster, act as a signaling center for specifying and maintaining the identity of the outer border cells during migration (Ghiglione et al., 2002; Silver and Montell, 2001). We wanted to examine whether the Bursicon ligand is sent from these inner polar cells to the outer border cells. Interestingly, neither pburs7 clones of polar cells alone nor of outer border cells alone had a substantial effect on border cell migration distance in Stage 10 egg chambers (Fig. 4C). This observation, along with the RNAi data from expression in all of the border cells, suggests that Bursicon is likely a diffusible ligand that is expressed in all border cells.

We investigated whether loss of Bursicon would also lead to the detachment and tethering phenotype that we had seen in the rk mutants. When we knocked down Burs alpha expression with burs alpha RNAi in all of the border cells, we observed tethers similar to those described in our live imaging and some of the fixed samples of rk RNAi expressing border cells (Fig. 4E, F and Fig. 2). GFP expression driven specifically in all border cells, together with either burs alpha RNAi or rk RNAi shows that these tethers are comprised of border cell membranes and not membranes from the nurse cells, as the tethers fluoresce with GFP (Fig. 4E, F).

In summary, the results of the analysis of the Bursicon ligand suggest that the Bursicon-Rickets ligand-receptor pair is used for communication between the border cells themselves.

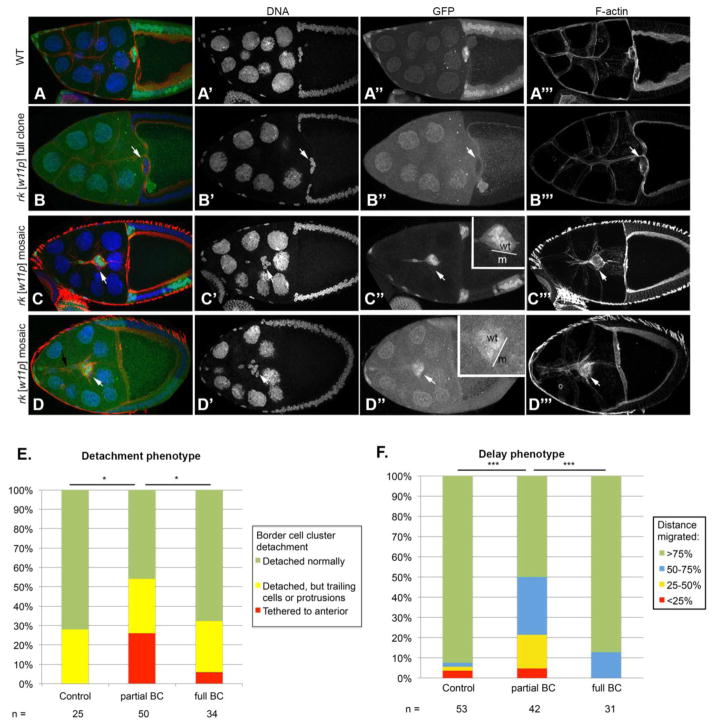

Mosaic rk border cell clusters exhibit a significantly more frequent detachment defect and migration delay

Close examination of the detachment phenotype in rkw11p mutant border cell clusters revealed that the phenotype is significantly more frequent in mosaic border cell clusters compared to clusters in which all of the border cells are mutant (Fig. 5). We re-examined late Stage 9 and Stage 10 rkw11p border cell clones, and separated these into two separate categories including full mutant border cell clusters, and partial or mosaic mutant border cell clusters. Partial mutant border cell clusters failed to cleanly detach from the epithelium and migrate as an intact cluster significantly more often than wild type border cells, whereas fully mutant border cell clusters were not significantly different from control cases (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, we also noted that trailing cells in the mosaic clusters were not always mutant (Fig. 1F, G and 5C, D

Figure 5. Mosaic border cell clusters exhibit migration delays and detachment defects.

(A–C) Stage 10 and (D) late Stage 9 egg chambers stained with Hoechst to label DNA (blue), and phalloidin to label F-actin (red). Mutant cells lack nuclear GFP (green). Anterior is to the left. (A) Control border cells in wildtype (WT; FRT40A line) completely detach from the anterior epithelium and have no lagging cells or protrusions. (B–D) Egg chambers containing rkw11p mutant border cells. (B) A full mutant border cell cluster that has completed its migration with no detachment defects. The arrow indicates a lack of trailing border cells. (C) A mosaic mutant border cell cluster exhibiting a migration delay and a lagging cell. The mutant cell in the cluster is indicated with an arrow. (C″) rkw11p mutant border cells lack GFP and are indicated with an arrow. The inset highlights the border cell cluster, indicating mutant (m) and wild type (wt) cells. (D) A late Stage 9 mosaic border cell cluster showing a large tether to the anterior epithelium (black arrow). The mutant cell lacks GFP (white arrow); emphasized in the inset in (D″). (E) Quantification of the detachment phenotype in rkw11p mutants, indicating frequency at which late Stage 9 and Stage 10 border cell clusters (BC) exhibit detachment phenotypes. Significance was determined with a Chi square test for independence. (F) Migration distance was scored for the rkw11p mutant at Stage 10, separating cases based on whether only some of the border cells are mutant, or the entire cluster is mutant. Significance was determined with a Chi square test for independence.

In additon to the detachment phenotype, the migration delay exhibited by rk mutant border cells was also significantly more penetrant in partial mutant border cell clusters than in control and full mutant border cell clusters (Fig. 5F). We examined the distance migrated by border cell clusters at Stage 10 relative to the distance that wild type border cell clusters would normally migrate and found that mosaic rkw11p mutant border cell clusters were significantly delayed in their migration compared to control clones, whereas full rkw11p mutant border cell clusters were not (Fig. 5F).

It is worth noting that, as described earlier, border cells in egg chambers that express slbo-Gal4 driven rk RNAi in the border cells also exhibit border cell migration defects (Fig. 3E; Supplemental Movies). In order to determine why the RNAi phenotype is consistent with the phenotype we see with rk mosaic clusters, and not rk full mutant clusters, we examined expression of UAS-GFP levels driven by the RNAi drivers that we utilized. The Gal4 drivers utilized result in patchy expression of the target UAS constructs, as observed by varying levels of UAS-GFP driven within border cell clusters (Supplemental Fig. S1A′), resembling the effect of mosaic mutant border cell clusters. Patchy expression of UAS target genes by Gal4 constructs has been previously described (Skora and Spradling, 2010; Hudson and Cooley, 2014).

We further considered the possibility that clones in the anterior follicular epithelium in the cells from which the border cells detach could be responsible for the detachment phenotype in mosaic border cell clusters. However, there was no significant difference in the detachment defects of mosaic border cells that had rkw11p mutant anterior clones (n = 29) versus those that did not (n = 7).

Altogether, these data demonstrate that rk mutants exhibit strong border cell migration defects in mosaic border cell clusters, in which some of the border cells are mutant and some are wild type. Border cell clusters containing either all wild type or all mutant cells exhibit only minor detachment problems or migration delays. These results indicate that border cells seem to require more uniform levels of Rk signaling throughout the cluster; problems occur if some cells can receive and transduce signal and others cannot. We also observed that the border cells within a mosaic cluster that are attached by an anterior tether or lagging behind can have either a wild type, or a mutant genotype which we interpret to reflect disrupted communication among mosaic cells within the collectively migrating cluster (Fig. 1, 5). Our results suggest that the detachment phenotype observed in rk mosaic border cell clusters is not a result of individual cell behavior within the cluster, but instead caused by non-uniform communication among the cells, and disrupted group behavior.

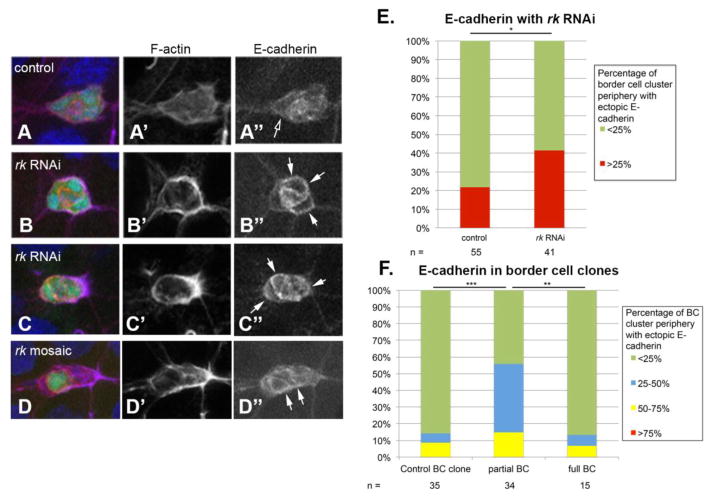

E-cadherin localization is abnormal in border cells with disrupted rk expression, particularly in mosaic border cell clusters

After observing the effects of rk mutations on the ability of border cells to transition from epithelial cells to a fully detached migratory cell cluster, we wanted to investigate whether Rk signaling was influencing the adhesion of the border cells. During border cell migration, E-cadherin normally exhibits strong localization to the interfaces between border cells, and only lower levels of localization around the periphery of the border cell cluster where the border cells contact the nurse cells (Niewiadomska et al., 1999; Pinheiro and Montell, 2004). When we analyzed border cell clusters expressing rk RNAi, we observed ectopic high levels of E-cadherin localization in patches around the periphery of the border cell cluster compared to wild type controls (Fig. 6A–C). We assessed mislocalization of E-cadherin during migration by recording the fraction of the border cell cluster periphery that showed high levels of E-cadherin. High levels of E-cadherin were determined by comparing the levels of E-cadherin on the periphery, with the normally high E-cadherin levels at the border cell-border cell interfaces within the border cell clusters. We collected Z stacked images of the entire border cell cluster and generated maximum intensity projections. This technique provided a full view of the border cells and accurately allowed us to determine which cell interfaces had highest levels of E-cadherin present. Once we recorded the fraction of the cluster’s periphery containing ectopic high levels of E-cadherin, we then quantified the frequency with which we saw border cell clusters with more than 25% of the periphery exhibiting high E-cadherin levels.

Figure 6. E-cadherin is mislocalized in border cell clusters lacking rk.

(A–D) E-cadherin localization in migrating border cells (BC) in control, rk RNAi expressing border cells, and rkw11p mosaic border cells. rk RNAi was driven in all border cells with both upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Controls express Gal4 drivers alone. Egg chambers were stained with Hoechst to label DNA (blue), phalloidin to label F-actin (purple), and an antibody against E-cadherin (red). Egg chambers are oriented with anterior to the left. (A–C) UAS-eGFP (green) reports the expression pattern of the upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 drivers. (D) The lack of GFP fluorescence indicates rkw11p mutant border cells. (A) The lower levels of peripheral E-cadherin in control clusters is indicated with an open arrow. (B–D) Ectopic peripheral E-cadherin is indicated with a closed arrow. (E) The percentage of the border cell cluster (BC) periphery occupied with ectopic E-cadherin was quantified in control and rk RNAi expressing border cell clusters. Significance was determined with a Chi square test for goodness of fit. (F) The percentage of the border cell cluster periphery with ectopic E-cadherin localization was quantified in rkw11p mosaic, and full mutant border cells. Significance was determined with a Chi square goodness of fit test, comparing the percentage of border cells with little E-cadherin around the periphery to the percentage of those with E-cadherin around more than 25% of the periphery.

Specifically, rk RNAi-expressing border cell clusters have E-cadherin upregulated around a large portion of the cluster periphery significantly more often than control border cells (Fig. 6E). We performed a similar analysis of E-cadherin localization in rkw11p border cell clones, and found that partial mutant border cell clusters exhibited a mislocalization phenotype, while full mutant clones did not show a significant difference compared to wild type controls (Fig. 6D, F). Of the 34 mosaic border cell clusters that we observed, we re-evaluated 13 clusters with ectopic peripheral E-cadherin that we could confidently assign to the boundaries of mutant or wild type cells. We found 5 cases in which ectopic E-cadherin was solely localized over mutant cells, 3 instances in which it was only localized over wild type cells, and 5 cases in which it was localized over both mutant and wild type cells within the same cluster. This evaluation shows that ectopic E-cadherin can also accumulate over wild type cells, and suggests that there is no bias of ectopic E-cadherin localizing over mutant vs. wild type cells in the mosaic clusters. This analysis strongly supports the finding that it is not the individual mutant cells within a mosaic cluster that are responsible for the migration defects; the defects are a result of non-uniform communication among the border cells as a collective group.

We wanted to ask whether clones in the anterior-most follicle cells from which the border cells detach caused the observed E-cadherin mislocalization phenotype in mosaic border cells. We analyzed E-cadherin localization in egg chambers with rkw11p mosaic border cells that also had mutant anterior follicle cells, and there was no significant difference in the E-cadherin mislocalization phenotype in these egg chambers (n = 29) compared with the mislocalization in egg chambers without anterior clones (n = 7). This analysis further supports the model that communication among the border cells themselves is responsible for the E-cadherin localization phenotype.

These border cell clusters that exhibit ectopic high levels of E-cadherin around the cluster periphery also appear to express high levels of F-actin. We observed that in 83% of the mosaic border cell clusters in which there is misexpression of E-cadherin, we also observe high levels of F-actin co-localized with E-cadherin (n = 24). We attribute this observation to the fact that E-cadherin links to F-actin through its interaction with catenins (Roy and Berx, 2008; Weis and Nelson, 2006), and could thus be recruiting or stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton.

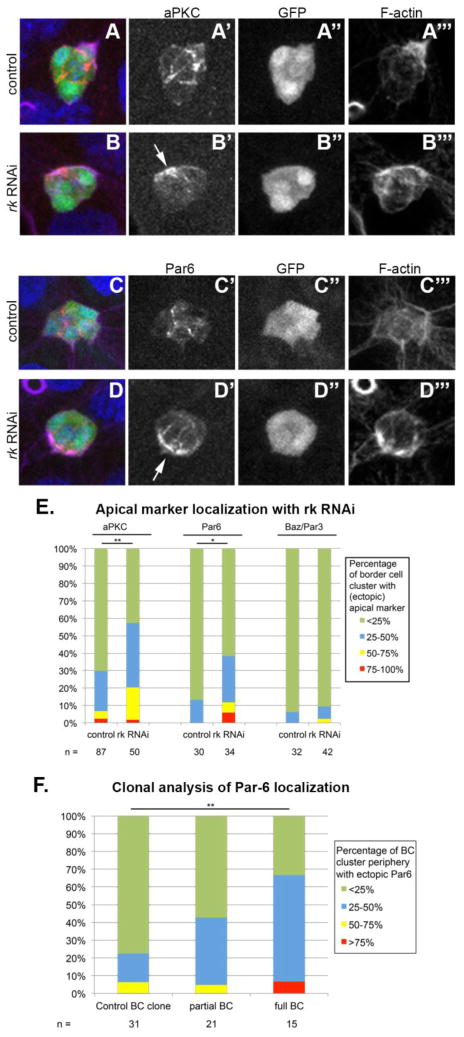

Apical polarity markers are mislocalized when rk expression is disrupted in the border cells

The phenotype of individual border cells trailing behind the main cell cluster that we observe when rk is disrupted is reminiscent of the phenotype that is observed when border cells lack apical polarity proteins Par-6 and Baz (Pinheiro and Montell, 2004). Border cells lacking Par-6 or Baz have adhesion defects and exhibit mispositioning of the adhesion protein E-cadherin (Pinheiro and Montell, 2004, Fig. S1). Due to the relationship between adhesion and polarity proteins during border cell migration and other cellular processes (St. Johnston and Sanson, 2011), we were consequently interested in whether polarity markers are affected in border cells with disrupted rk, especially since these border cells often mislocalize E-cadherin.

In wild-type border cells that are undergoing migration, apical markers are localized mainly to the border cell-border cell interfaces and the border cell-polar cell interfaces in contrast to the border cell-nurse cell boundaries (McDonald et al., 2008). We observed a clear mislocalization of apical polarity markers atypical Protein Kinase C (aPKC) and Par-6 in border cells expressing rk RNAi to the periphery of the cluster (Fig. 7). Similar to our E-cadherin analysis, we recorded the fraction of the periphery that is occupied by the polarity protein. We then determined the frequency of border cell clusters with more than 25% of the periphery occupied by apical polarity markers. We found that such an abnormally high percentage of the periphery being occupied by either aPKC or Par-6 was more frequently observed in rk RNAi border cell clusters than in control clusters (Fig. 7). We did not observe a significant difference in Baz localization in rk RNAi border cells compared to control (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7. Apical polarity marker mislocalization in border cell clusters lacking rk.

(A–D) Apical polarity marker localization in migrating border cells (BC) in control and rk RNAi egg chambers. Egg chambers are oriented with anterior to the left. rk RNAi was driven in all border cells with both upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Controls express Gal4 drivers alone. Egg chambers with migrating border cells were stained with Hoechst to label DNA (blue), phalloidin to label F-actin (purple), and antibodies to label either (A–B) aPKC or (C–D) Par-6 localization (red). UAS-eGFP reports the expression pattern of the upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 drivers. (B, D) Arrows indicate ectopic peripheral apical marker localization. (E) The percentage of the border cell cluster periphery occupied with ectopic aPKC or Par-6 was quantified in control and rk RNAi expressing border cell clusters. Significance was determined with a Chi square test for independence. (F) The percentage of the border cell cluster periphery with ectopic Par-6 localization was quantified in rkw11p mosaic, and full mutant border cells. Significance was determined with a Chi square goodness of fit test, comparing the percentage of border cells with little aPKC or Par-6 around the periphery to the percentage of those with the marker around more than 25% of the periphery.

We performed a similar analysis of Par-6 mislocalization in rkw11p border cell clones, and observed ectopic Par-6 at the border cell cluster periphery in both full and partial border cell cluster clones. The Par-6 mislocalization phenotype was stronger in full mutant border cell clusters than in mosaic mutant clusters (Fig. 7F).

These results indicate that in the absence of Rk signaling, the border cells frequently lose the normal distribution of polarity proteins. Thus, it appears that Rk signaling is also involved in regulating the polarity of the border cell cluster, but this does not appear to be the main cause of the detachment and migration defects, since high frequencies of mislocalization in fully mutant clusters do not translate into increased detachment and migration defects.

Discussion

Rickets is not a guidance receptor

Our data shows expression of the G-protein-coupled receptor Rickets (Rk) in the border cell cluster, and indicates that the Rk ligand Bursicon is only required in the border cells. Bursicon is a heterodimer comprised of Bursicon alpha (Burs) and Partner of bursicon (Pburs) (Luo et al., 2005; Mendive et al., 2005), and full germline mutant clones of pburs7 do not exhibit delays in border cell migration. Migration delays are observed only when burs alpha RNAi is expressed in the border cells themselves. This demonstrates that only Bursicon expressed in the border cells is important for border cell migration. This scenario is in contrast to that of the guidance receptors PDGF- and VEGF-receptor related (PVR) and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), that are also localized on the border cells, but where ligand emanates from the oocyte and serves as directional guidance cue (Duchek and Rorth, 2001; Duchek et al., 2001; McDonald et al., 2003). Furthermore, our live imaging data shows that border cells expressing rk RNAi extend protrusions correctly in the forward direction of migration towards the oocyte. Our results therefore support the conclusion that unlike the PVR and EGFR receptors, Rk does not function as a guidance receptor, but participates in intercellular communication within the border cell cluster itself and receives the Bursicon signal produced in all border cells. In collective cell migration, it is necessary for cells to communicate with each other, possibly concerning coordinated speed and detachment timing. In addition, cells need to relay information from the cells at the front, which extend protrusions and serve as leaders, to follower cells at the rear. These differences need to be established and maintained.

While it is presently not entirely clear what type of information is communicated between the border cells with help of Rk signaling, it is more likely that Rk is involved in a general coordination of border cell processes than in establishing a difference between the leaders and the followers, given that forward protrusions seem to be correctly initiated in and restricted to the cells at the front, even in the mutant clusters.

A uniform level of Rickets signaling throughout the border cells is important for proper border cell migration

Our clonal analysis indicated that it is more detrimental to border cell migration when only a portion of the outer border cells lack Rk expression compared to fully mutant clusters. The distance to which the border cells are able to migrate by Stage 10 of oogenesis is significantly reduced in mosaic border cell clusters. In addition, the border cell cluster exhibits detachment defects significantly more often when part of the cluster is mutant than it does in control cases, or in cases in which the entire cluster is mutant. Full mutant border cells exhibit some delays in border cell migration relative to controls, and occasionally remain tethered to the epithelium. But these defects are slight, compared to the significant defects observed in the mosaic clusters.

Our results show that when Rk signaling is not uniform, border cell migration is defective and E-cadherin is redistributed so that high levels are now localized around the periphery of the border cell cluster, instead of being restricted to the border cell-border cell interfaces. This redistribution likely causes the adhesive forces between the border cells and the substrate over which they migrate to compete with the forces within the cluster itself, which may cause the observed tethers and prevent detachment. Alternatively, it is possible that non-uniform Rk signaling affects the ability of the cells at the back of the border cell cluster to sever their connections with the epithelium, and that the resulting force from the tethers is what causes E-cadherin to redistribute in affected border cell clusters. This scenario could explain why E-cadherin is found over wild type and mutant cells without discrimination. E-cadherin has been reported to play a role in directing transmission of force (Rauzi et al., 2010; Sim et al., 2015), for example in the Drosophila blastoderm epidermis when actomyosin flow directed by E-cadherin transmits tension required for morphogenesis (Rauzi et al., 2010). We therefore favor the first model, but we cannot rule out the second. An overall redistribution and competition of forces could be the cause of the migration defects for the entire cluster. We found that the genotype of individual cells within a mosaic cluster as wild type or rk mutant does not determine whether these specific cells will be caught in an anterior tether, or express ectopically high E-cadherin levels. Instead, the identity of the entire group of cells as mosaic, and hence non-uniform, correlates to migration defects in the cluster overall.

Cell-cell communication is known to inform collective decision making in the border cells. In these instances, all of the cells within the migrating cluster must retain equivalent ability to communicate with one another in order for signals to be properly interpreted by the entire group of cells. Uniform activity of Rab11 in all of the border cells has been shown to be necessary for regulating intercellular communication, thereby allowing the border cells to activate Rac in response to guidance cues in only one cell at the leading edge of the cluster. Disruption of Rab11 in some of the border cells prevents them from communicating information about which cell is the leader, and as a result the border cells exhibit protrusions in inappropriate directions (Emery and Ramel, 2013; Ramel et al., 2013). Uniform communication among the border cells downstream of Rab11 has thus been implicated in identifying the leader cell, similar to our observation that uniform communication among border cells is necessary for the cluster to regulate its overall detachment at the back of the cluster.

Rk signaling in the wing has been shown to utilize cyclic AMP and the kinase PKA as downstream effectors (Baker and Truman, 2002; Kimura et al., 2003). To our knowledge, the only known role of PKA in the Drosophila ovary follicle cells involves negative regulation of the Hedgehog pathway. PKA follicle cell mutant clones exhibit excess Hedgehog signaling and have extra polar cells and border cells (Zhang and Kalderon, 2000), which we do not see in our rk clones. In other tissues, PKA is known to phosphorylate many small GTPases and GEFs that influence cell migration (Breckler et al., 2011). PKA can phosphorylate the small GTPase Rap1, thus enabling migrating cells to break adhesions and detach from the substratum over which they are moving (Takahashi et al., 2013). Activation of small GTPases is also known to regulate polarity proteins that are key for propagating and maintaining cell polarity domains through phosphorylation events (St Johnston and Ahringer, 2010; St Johnston and Sanson, 2011; Tepass et al., 2001). It is possible that PKA phosphorylation events downstream of Rk signaling target proteins involved in force generation, detachment or adhesion that should have comparable levels of activity in all of the border cells in order to allow the cluster to move as a whole. For example, if in mosaics a particular adhesion molecule were more active in a few cells compared to others, this might contribute to the migration difficulties observed in the clusters. It is therefore possible that in addition to regulating polarity proteins (see below), Rk signaling also is important to maintain an even migration capacity within the cells of the cluster.

Rickets signaling affects distribution of E-cadherin, as well as the polarity proteins Par-6 and aPKC, in the migrating border cells

The rk mutations, as well as rk RNAi expressed in the border cells, result in mislocalization of the adhesion protein E-cadherin and the apical polarity proteins Par-6 and aPKC. Mislocalization was indicated by a significantly higher number of border cell clusters expressing E-cadherin at high levels, Par-6, or aPKC around a substantial portion of the periphery of the migrating border cell cluster relative to controls. These results indicate that Rk signaling is regulating the normal distribution of these proteins. Considering apical polarity proteins, we note that rk disruption affects the positioning of aPKC and Par-6, but not of Bazooka. The coordinated effects on Par-6 and aPKC in contrast to Bazooka are maybe not surprising, since it is known that aPKC and Par-6 are part of the same apical complex during tissue polarization, whereas Baz is regulated differently in both the Drosophila blastoderm and the C. elegans embryo (Achilleos et al., 2010; Harris and Peifer, 2005; Totong et al., 2007).

Our clonal analysis of E-cadherin and Par-6 localization in rkw11p mosaic and full mutant border cell clusters suggests that Rk might affect E-cadherin and Par-6 independently. E-cadherin localization was disrupted in mosaic clusters, but was not substantially affected in full mutant clusters. In contrast, Par-6 localization was affected in mosaics, and was even more notably disrupted in the full mutant clusters. This disruption of Par-6 localization in full mutants could account for the slight delay and detachment defects that were observed when the entire border cell cluster was mutant. The observation that Par-6 and E-cadherin localizations are not affected in the same pattern in the full mutant border cells argues for Rk acting on these two proteins separately.

rk mutants show a strong detachment phenotype in which the border cell cluster remains tethered to the original epithelium

Our fixed samples and live imaging experiments have allowed us to describe a detachment defect in which a migrating cluster of mutant border cells remains “tethered” to the anterior epithelium. Very interestingly, the crucial element in this defect relates to the inability of one or two cells at the back of the border cell cluster to break their connections with anterior epithelial cells. As a result, the main border cell cluster tries to move forward as expected, but the rear-most border cells become stretched across the migration path. They remain attached to both the egg chamber epithelium and the migrating border cells, forming a “tether” (Figs. 1,2,5, and supplemental movies). In other examples, the main border cell cluster was apparently retracted back to the epithelium by the still-attached rear end cells. Occasionally, the stretching of the cells within the tether caused the tether to break and these cells to detach from the main cluster. Our clonal analysis indicates that this behavior is not only restricted to mutant cells.

It is possible that the defects in E-cadherin localization are causing the tethered phenotype and detachment problems when rk expression is compromised. The detachment phenotype is significantly stronger in mosaic border cell clusters than it is in control and full mutant clusters. Since this correlates well with the E-cadherin mislocalization phenotype but not with the mislocalization of Par-6, it might suggest that the E-cadherin problems are causing the detachment phenotype. Indeed, it has been reported that upregulation and mislocalization of E-cadherin in the border cells results in a severe detachment and migration phenotype (Schober et al., 2005; Bai and Montell, 2000; Gunawan et al., 2013). However, such a scenario might not fully explain why the major problem due to loss of Burs-Rk signaling appears to arise in the one or two border cells that find themselves at the rear of the cluster. E-cadherin upregulation is seen all around the border cell-nurse cell interface and is not particularly concentrated at the rear. It is therefore also possible that in addition to the regulation of polarity proteins and E-cadherin, Rk relays information specifically regulating a process that should result in the cells at the rear end to sever attachments to the epithelium. It has been suggested that the cells with the highest input from the guidance receptors assume the leader position (Ducheck and Rorth, 2001; Wang et al., 2010). They may initiate general Bursicon secretion in all border cells and thus signal to the other cells to move forward in a coordinated manner. Rickets activity might lead to a general regulation of both the expression and distribution of polarity proteins and E-cadherin, as well as providing a distinct timing signal to induce full detachment from the epithelium. With disrupted Rk signaling, it would then seem likely that such processes are not properly coordinated and executed, leading to the observed migration defects that seem to affect the rear end cells in particular, possibly because they are predicted to have the lowest level of guidance receptor signaling. In order to fully resolve these questions, it will be important to determine the targets of Rk signaling in the border cells in the future.

In summary, we have identified a G-protein-coupled receptor that functions in intercellular communication within the border cell cluster to coordinate polarity and detachment events. Characterizing Rk signaling further will be informative for understanding how intercellular communication can regulate different steps of collective cellular migration, an important process in development as well as in disease states.

Supplementary Material

(A–C) Egg chambers with migrating border cells stained with an antibody against E-cadherin (red). Cell nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue), and F-actin is labeled with phalloidin (purple). Egg chambers are oriented with anterior to the left. (A) Control egg chambers expressing upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 drivers, with a UAS-eGFP marker to visualize Gal4 expression patterns. Open arrow indicates low levels of E-cadherin around the periphery of the border cell cluster. (B) Egg chambers expressing RNAi against aPKC, driven in all of the border cells by upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Closed arrow indicates high levels of E-cadherin around the periphery of the border cell cluster. (C) Egg chambers expressing RNAi against par-6, driven in all of the border cells by upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Closed arrow indicates high levels of E-cadherin around the periphery of the border cell cluster. (D) Quantification of the percentage of the border cell cluster periphery occupied by E-cadherin in control egg chambers or egg chambers expressing par-6 RNAi, or aPKC RNAi. Significance was determined with a Chi square goodness of fit test.

gap43-mCherry border cells at the anterior of the egg chamber form a cluster, and extend forward protrusions towards the oocyte. They subsequently detach and begin migration. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 7.65 hr.

gap43-mCherry border cells at the anterior of the egg chamber form a cluster, and extend forward protrusions towards the oocyte. They then detach and migrate. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 2.6 hr.

slbo-Gal4; rk RNAi / gap43-mCherry border cells form a cluster and extend forward protrusions, but do not successfully detach. Protrusions are retracted. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 4.55 hr.

The slbo-Gal4; rk RNAi / gap43-mCherry border cell cluster extends forward protrusions, and migrates towards the oocyte. During migration, the cluster remains attached to the anterior epithelium via a stretched cellular tether. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 3.25 hr.

This slbo-Gal4; rk RNAi / gap43-mCherry border cell cluster begins migration with a stretched cellular tether attaching it to the anterior epithelium. During migration, the tether breaks, and the cells closest to the epithelium retract backwards to the epithelium. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 2.80 hr.

Highlights.

rickets mutations disrupt detachment and migration of border cells during Drosophila oogenesis.

Border cell clusters are aberrantly tethered to the epithelium in rickets mutants.

Mosaic rickets mutant border cell clusters exhibit more severe defects than full mutants.

Rickets signaling is used for communication among the border cells themselves.

E-cadherin and polarity proteins are mislocalized in rk mosaic mutant border cell clusters.

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin H. White, Stephane Noselli, Adam C. Martin, John Kiger, Daniel Kalderon, John Ewer, the Bloomington Stock Center, and the Vienna Stock Center for sending Drosophila stocks. We also thank Denise J. Montell, Benjamin H. White, Jennifer A. Zallen, Pernille Rorth, Stephane Noselli and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for providing antibodies. We are grateful to Elena Domanitskaya and Yi Sun for performing the initial mutagenesis screen, and Gary Laevsky for support with microscopy. We thank Shelby Blythe, Bing He, Danelle Devenport, Olivier Devergne, and Julie Merkle for their comments on the manuscript, and Schüpbach and Wieschaus laboratory members for feedback and advice. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health pre-doctoral fellowship grant 1F31 GM111006-01 and by US Public Health Service Grant RO1 GM077620.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

LA and TS conceived, discussed and designed the experiments. LA performed the experiments and analyzed the data. LA and TS wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achilleos A, Wehman AM, Nance J. PAR-3 mediates the initial clustering and apical localization of junction and polarity proteins during C. elegans intestinal epithelial cell polarization. Development. 2010;137:1833–1842. doi: 10.1242/dev.047647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. Drosophila: A laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Uehara Y, Montell DJ. Regulation of invasive cell behavior by Taiman, a Drosophila protein related to AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast cancer. Cell. 2000;103:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JD, Truman JW. Mutations in the Drosophila glycoprotein hormone receptor, rickets, eliminate neuropeptide-induced tanning and selectively block a stereotyped behavioral program. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:2555–2565. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.17.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer EM, Konstantopoulos K. Intercellular adhesion: mechanisms for growth and metastasis of epithelial cancers. Wiley Interdiscp Rev Syst Biol Med. 2012;4:171–181. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese L, Fletcher G, Mathieu J, Atzberger A, Eades WC, Cagan RL, Rorth P. Systematic analysis of the transcriptional switch inducing migration of border cells. Dev Cell. 2006;10:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckler M, Berthouze M, Laurent AC, Crozatier B, Morel E, Lezoualc’h F. Rap-linked cAMP signaling Epac proteins: compartmentation, functioning and disease implications. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant K, Knowles BA, Mooseker MS, Cooley L. Drosophila Singed, a Fascin homolog, is required for actin bundle formation during oogenesis and bristle extension. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:369–380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Fontaine C, Matthews HK, Kuriyama S, Moreno M, Dunn GA, Parsons M, Stern CD, Mayor R. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature. 2008;456:957–961. doi: 10.1038/nature07441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano Z, Tracy K, McAllister SS. The tumor macroenvironment and systemic regulation of breast cancer progression. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:889–897. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.113366zc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef N, Chen Y, Weeks SD, Barcelo G, Schüpbach T. Crag regulates epithelial architecture and polarized deposition of basement membrane proteins in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2008;14:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey EM, McNabb SL, Ewer J, Kuo GR, Takanishi CL, Truman JW, Honegger H. Identification of the gene encoding Bursicon, an insect neuropeptide responsible for cuticle sclerotization and wing spreading. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao F, White BH. A novel approach for directing transgene expression in Drosophila: T2A-Gal4 in frame fusion. Genetics. 2012;190:1139–1144. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanitskaya E, Anllo L, Schüpbach T. Phantom, a cytochrome P450 enzyme essential for ecdysone biosynthesis, plays a critical role in the control of border cell migration in. Drosophila Dev Biol. 2014;386:408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchek P, Rorth P. Guidance of cell migration by EGF receptor signaling during Drosophila oogenesis. Science. 2001;291:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchek P, Somogyi K, Jekely G, Beccari S, Rorth P. Guidance of cell migration by the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor. Cell. 2001;107:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JB, Harrison DA, Perrimon N. Identifying loci required for follicular patterning using directed mosaics. Development. 1998;125:2263–2271. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery G, Ramel D. Cell coordination of collective migration by Rab 11 and Moesin. Communicative & Integrative Biol. 2013;6:e24587. doi: 10.4161/cib.24587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen KK, Hauser F, Schiott M, Pedersen KM, Sondergaard L, Grimmelikhuijzen CJP. Molecular cloning, genomic organization, developmental regulation and a knock-out mutant of a novel Leu-rich repeats-containing G Protein-coupled Receptor (DLGR-2) from. Drosophila melanogaster Genome Res. 2000;10:924–938. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Rebay I, Hynes RO. Expression of DFak56, a Drosophila homolog of vertebrate focal adhesion kinase, supports a role in cell migration. in vivo Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14978–14983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Bronner-Fraser M. Neural crest specification: migrating into genomics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:795–805. doi: 10.1038/nrn1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione C, Devergne O, Goergenthum E, Carballes F, Medioni C, Cerezo D, Noselli S. The Drosophila Cytokine receptor Domeless controls border cell migration and epithelial polarization during oogenesis. Development. 2002;129:5437–5447. doi: 10.1242/dev.00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan F, Arandjelovic M, Godt D. The Maf factor Traffic jam both enables and inhibits collective cell migration in Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2013;140:2808–2817. doi: 10.1242/dev.089896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TJC, Peifer M. The positioning and segregation of apical cues during epithelial polarity establishment in. Drosophila J Cell Biol. 2005;170:813–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AM, Cooley L. Methods for studying oogenesis. Methods. 2014;68:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger JA, Jr, Natzle JE, Kimbrell DA, Paddy MR, Kleinhesselink K, Green MM. Tissue remodeling during maturation of the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2007;301:178–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Kodama A, Hayasaka Y, Ohta T. Activation of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway is required for post-ecdysial cell death in wing epidermal cells of Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2003;131:1597–1606. doi: 10.1242/dev.01049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie YS, Macdonald PM. Apontic binds the translational repressor Bruno and is implicated in regulation of oskar mRNA translation. Development. 1999;126:1129–1138. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llense F, Martin-Blanco E. JNK signaling controls border cell cluster integrity and collective cell migration. Curr Biol. 2008;18:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveall BJ, Deitcher DL. The essential role of bursicon during Drosophila development. BMC Developmental Biology. 2010;10:92–119. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo CW, Dewey EM, Sudo S, Ewer J, Hsu SY, Honegger H, Hsueh AJ. Bursicon, the insect cuticle-hardening hormone, is a heterodimeric cysteine knot protein that activates G protein-coupled receptor LGR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2820–2825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409916102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AC, Gelbart M, Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Kaschube M, Wieschaus EF. Integration of contractile forces during tissue invagination. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:735–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Khodyakova A, Aranjuez G, Dudley C, Montell DJ. PAR-1 Kinase regulates epithelial detachment and directional protrusion of migrating border cells. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1659–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Pinheiro EM, Montell DJ. PVF1, a PDGF/VEGF homolog, is sufficient to guide border cells and interacts genetically with Taiman. Development. 2003;130:3469–3478. doi: 10.1242/dev.00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendive FM, Loy TV, Claeysen S, Poels J, Williamson M, Hauser F, Grimmelikhuijzen CJP, Vassart G, Broeck JV. Drosophila molting neurohormone bursicon is a heterodimer and the natural agonist of the orphan receptor DLGR2. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2171–2176. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell DJ. Border-cell migration: the race is on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell DJ, Rorth P, Spradling AC. slow border cells, a locus required for a developmentally regulated cell migration during oogenesis, encodes Drosophila C/EBP. Cell. 1992;71:51–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90265-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell DJ, Yoon WH, Starz-Gaiano M. Group choreography: mechanisms orchestrating the collective movement of border cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:631–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natzle JE, Kiger JA, Jr, Green MM. Bursicon signaling mutations separate the epithelial-mesenchymal transition from programmed cell death during Drosophila melanogaster wing maturation. Genetics. 2008;180:885–893. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.092908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomska P, Godt D, Tepass U. DE-Cadherin is required for intercellular motility during Drosophila oogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:533–547. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody NC, Diao F, Luan H, Wang H, Dewey EM, Honegger H, White BH. Bursicon functions within the Drosophila CNS to modulate wing expansion behavior, hormone secretion, and cell death. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14379–14391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2842-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro EM, Montell DJ. Requirement for Par-6 and Bazooka in Drosophila border cell migration. Development. 2004;131:5243–5251. doi: 10.1242/dev.01412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad M, Jang AC, Starz-Gaiano M, Melani M, Montell DJ. A protocol for culturing Drosophila melanogaster stage 9 egg chambers for live imaging. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2467–2473. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel D, Wang X, Laflamme C, Montell DJ, Emery G. Rab11 regulates cell-cell communication during collective cell movements. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:317–324. doi: 10.1038/ncb2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauzi M, Lenne P, Lecuit T. Planar polarized actomyosin contractile flows control epithelial junction remodelling. Nature. 2010;468:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nature09566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J, Gauert A, Montecinos LB, Kabla A, Hartel S, Linker C. Leader cells define directionality during collective cell migration Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P. Initiating and guiding migration: lessons from border cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:325–331. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Roy F, Berx G. The cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3756–3788. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M. A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nrm2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savagner P. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenomenon. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:vii89–vii92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober M, Rebay I, Perrimon N. Function of the ETS transcription factor Yan in border cell migration. Development. 2005;132:3493–3504. doi: 10.1242/dev.01911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver DL, Montell DJ. Paracrine signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway activates invasive behavior of ovarian epithelial cells in Drosophila. Cell. 2001;107:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver DL, Geisbrecht ER, Montell DJ. Requirement for JAK/STAT signaling throughout border cell migration in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:3483–3492. doi: 10.1242/dev.01910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim JY, Moeller J, Hart KC, Ramallo D, Vogel V, Dunn AR, Nelson WJ, Pruitt BL. Spatial distribution of cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions regulates force balance while maintaining E-cadherin molecular tension in cell pairs. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2456–2465. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-12-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skora AD, Spradling AC. Epigenetic stability increases extensively during Drosophila follicle stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7389–7394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003180107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Ahringer J. Cell polarity in eggs and epithelial: parallels and diversity. Cell. 2010;141:757–774. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Sanson B. Epithelial polarity and morphogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling AC. Developmental genetics of oogenesis. In: Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. The Development of Drosophila Melanogaster. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Dillon TJ, Liu C, Kariya Y, Wang Z, Stork PJ. Protein Kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of Rap1 regulates its membrane localization and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:27712–27723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U, Tanentzapf G, Ward R, Fehon R. Epithelial cell polarity and cell junctions in. Drosophila Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:747–784. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totong R, Achilleos A, Nance J. PAR-6 is required for junction formation but not apicobasal polarization in C. elegans embryonic epithelial cells. Development. 2007;134:1259–1268. doi: 10.1242/dev.02833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valluru M, Staton CA, Reed MWR, Brown NJ. Transforming growth factor Beta and endoglin signaling orchestrate wound healing. Front Physiol. 2011;2:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, He L, Wu YI, Hahn KM, Montell DJ. Light-mediated activation reveals a key role for Rac in collective guidance of cell movement. in vivo Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:591–597. doi: 10.1038/ncb2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Re-solving the cadherin-catenin-actin conundrum. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35593–35597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600027200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kalderon D. Regulation of cell proliferation and patterning in Drosophila oogenesis by Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2000;127:2165–2176. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A–C) Egg chambers with migrating border cells stained with an antibody against E-cadherin (red). Cell nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue), and F-actin is labeled with phalloidin (purple). Egg chambers are oriented with anterior to the left. (A) Control egg chambers expressing upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4 drivers, with a UAS-eGFP marker to visualize Gal4 expression patterns. Open arrow indicates low levels of E-cadherin around the periphery of the border cell cluster. (B) Egg chambers expressing RNAi against aPKC, driven in all of the border cells by upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Closed arrow indicates high levels of E-cadherin around the periphery of the border cell cluster. (C) Egg chambers expressing RNAi against par-6, driven in all of the border cells by upd-Gal4 and slbo-Gal4. Closed arrow indicates high levels of E-cadherin around the periphery of the border cell cluster. (D) Quantification of the percentage of the border cell cluster periphery occupied by E-cadherin in control egg chambers or egg chambers expressing par-6 RNAi, or aPKC RNAi. Significance was determined with a Chi square goodness of fit test.

gap43-mCherry border cells at the anterior of the egg chamber form a cluster, and extend forward protrusions towards the oocyte. They subsequently detach and begin migration. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 7.65 hr.

gap43-mCherry border cells at the anterior of the egg chamber form a cluster, and extend forward protrusions towards the oocyte. They then detach and migrate. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 2.6 hr.

slbo-Gal4; rk RNAi / gap43-mCherry border cells form a cluster and extend forward protrusions, but do not successfully detach. Protrusions are retracted. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 4.55 hr.

The slbo-Gal4; rk RNAi / gap43-mCherry border cell cluster extends forward protrusions, and migrates towards the oocyte. During migration, the cluster remains attached to the anterior epithelium via a stretched cellular tether. Frame interval is 3 min; elapsed time is 3.25 hr.