Abstract

Background

Previous studies suggest that patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) who do not respond to treatment for depression are at higher risk of mortality than are treatment responders. The purpose of this study was to determine whether elevated nighttime heart rate (HR) and low heart rate variability (HRV), both of which have been associated with depression and with cardiac events in patients with CHD, predict poor response to depression treatment in patients with CHD.

Methods

Patients with stable CHD and a current major depressive episode completed 24 hour ambulatory ECG monitoring and were then treated for up to 16 weeks with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), either alone or in combination with an antidepressant. Pre-treatment HR and HRV were calculated for 124 patients who had continuous ECG from early evening to mid-morning.

Results

Following treatment, 64 of the 124 patients (52%) met study criteria for remission (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score < 7). Prior to treatment, non-remitters had higher nighttime HR (p=0.03) and lower nighttime HRV (p=0.01) than did the remitters, even after adjusting for potential confounds.

Limitations

Polysomnography would have provided information about objective sleep characteristics and sleep disorders. More CBT sessions and higher doses of antidepressants may have resulted in more participants in remission.

Conclusions

High nighttime HR and low nighttime HRV predict a poor response to treatment of major depression in patients with stable CHD. These findings may help explain why patients with CHD who do not respond to treatment are at higher risk for mortality.

Keywords: Depression treatment, nighttime heart rate, coronary heart disease

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a common comorbidity and a significant risk factor for cardiac morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) (Lichtman et al., 2014). Although the mechanisms of this risk are unclear, depression is associated with other risk factors for cardiac events including elevated heart rate (HR) and low heart rate variability (HRV) (Carney et al., 2005b; Kemp et al., 2010), dysfunctional sleep (Buysse et al., 1998; Ford et al., 1989), and blunted circadian HR rhythm (Stampfer, 1998; Taillard et al., 1990). Following an acute myocardial infarction (MI), for example, compared to non-depressed patients those with depression have higher nighttime HRs (Carney et al., 2008), lower heart rate variability (Carney et al., 2001), and a greater likelihood of having little or no decrease in nighttime HR relative to daytime levels (nocturnal dip) (Carney et al., 2014). All of these characteristics predicted mortality after adjusting for potential confounders.

Clinical trials that have examined whether treating depression can improve outcomes in cardiac patients have been limited by small numbers of cardiac endpoints and small post-treatment differences in depression between the intervention and control groups, and none have shown an effect on cardiac morbidity or mortality. However, secondary analyses of these trials have found that the risk for cardiac morbidity and mortality is elevated in patients who have minimal or no response to depression treatment (Carney et al., 2004; Carney et al., 2009). Cardiac patients who do not respond to depression treatment may remain at high risk for cardiac events simply because they continue to be depressed. However, it is also possible that these patients are at higher risk than those who do respond even before they are treated. That is, the factor(s) that place them at high risk for morbidity and mortality may also predict a poor response to depression treatment. Although little is known about predictors of treatment response in depressed patients with CHD, dysfunctional sleep and blunted circadian rhythms have predicted treatment response in depressed psychiatric patients (Buysse et al., 1999; Szuba et al., 2001) and mortality in patients with CHD (Laugsand et al., 2011).

The purpose of this study was to determine whether patients with stable CHD and major depression who failed to remit following treatment had higher nighttime HR and lower nighttime HRV before treatment than patients whose depression remitted.

METHODS

Eligibility Screening and Recruitment

Patients were recruited between May 2009 and August 2013 at cardiology offices and diagnostic laboratories affiliated with Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital of St. Louis. Consenting patients with CHD documented by coronary angiography, a history of coronary revascularization or hospitalization for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), completed the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Spitzer et al., 1999). Patients were excluded from the study if they had significant cognitive impairment, psychotic features, a comorbid psychiatric disorder other than an anxiety disorder, a high risk of suicide, current substance abuse, hospitalization for ACS or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery within the previous two months, advanced malignancy, a disability that would affect compliance with the study protocol, or physician or patient refusal. Patients who had been taking a guideline-recommended dose of an approved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant for at least 30 days were eligible to participate as long as all of the other eligibility criteria were met. Patients who were not excluded and who screened positive for depression on the PHQ-9 (total score >10) were scheduled for a structured clinical interview. Those who met the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode on the interview, scored >16 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), and gave written informed consent were enrolled. The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Psychiatric Assessments

Depression Interview and Structured Hamilton (DISH)

The DISH (Freedland et al., 2002) was administered at baseline and at 16 weeks to diagnose major depression according to the DSM-IV criteria and to measure the severity of depression on an embedded version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17). The DISH includes a screen for exclusionary psychiatric conditions, and assesses psychiatric history including previous major depressive episodes, psychiatric treatment, and family psychiatric history.

Beck Depression Inventory-II

The 21-item BDI- assesses the self-reported severity of depression symptoms (Beck et al., 1996). It was administered at baseline and 16-week evaluations.

Beck Depression Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The 21-item BAI measures the self-reported severity of anxiety symptoms (Beck et al., 1988). It was administered at the baseline and 16-week evaluations.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI (Buysse et al., 1989) assesses sleep quality including sleeping habits and specific sleep complaints during the past month. The PSQI global score was used as the primary index of sleep quality for this study, and was administered at the baseline and 16-week evaluations.

Laboratory Assessments

A blood specimen was drawn for standard laboratory tests after the patient rested supine on an examination table for 15 minutes. The patient was then fitted with an ambulatory ECG monitor for a 24 hour recording. The details of the blood testing and results are available elsewhere (Carney et al., 2016).

Ambulatory Electrocardiographic Monitoring

The ECG recordings were scanned at the HRV Core Laboratory at Washington University on a Cardioscan Holter scanner (Version 52a, DMS Holter, Stateside, NV) and analyzed with MARS Holter scanning software (Version 7.01, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). The labeled beat-to-beat file was exported to a Sun workstation (Sun Microsystems, Palo Alto, CA) for advanced HRV analysis. HRs were derived from at least three continuous normal-to-normal N-N intervals and averaged in 5-minute epochs. The interval between 7:00 pm and 9:00 am was chosen for analysis in order to sample HR activity before, during, and after typical periods of sleep.

The log of Very Low Frequency (ln VLF) power (0.0033-0.04hz in ms2) was chosen à priori as the index of HRV for this study based on evidence that it is lower in depressed compared to nondepressed patients with CHD, (Carney et al, 2001) and that it partially mediates the effect of depression on survival in these patients (Carney et al., 2005a). The methods used for spectral analysis of ambulatory ECG data have been described previously (Rottman et al., 1990).

All study personnel who had contact with the participants, including the CBT therapists, the psychiatrist, and the interviewers, were blinded to the results of all assessments.

Treatment

All participants received up to 12 sessions of CBT over four months. Telephone contacts by the therapist were permitted as needed during this time. The general principles and therapeutic techniques of the intervention were guided by published treatment manuals (Beck, 1995). Some of the standard cognitive-behavioral techniques were modified for use in cardiac patients, such as adapting behavioral activation plans to address medical safety concerns. More details of the CBT intervention are available elsewhere (Carney et al, 2016).

Participants who were receiving a therapeutic dose of an SSRI antidepressant for at least four weeks prior to enrollment received CBT while remaining on the same antidepressant for the duration of the study. Those who were not taking an antidepressant at enrollment initially received only CBT. However, if their BDI-II score did not decrease >30% by the 5th week of treatment, or >50% by the 8th week, they were prescribed a maximum dose of 100 mg of sertraline per day until the end of the 16-week treatment period. Sertraline has been shown to be safe in depressed cardiac patients. However, higher doses of sertraline were not prescribed as they only marginally increase response rates while substantially increasing side effects (Fabre et al., 1995; Schweizer et al., 2001). Thus, participants were given up to two recognized depression treatments during the four-month treatment period. Failure to respond to adequate trials of at least two recognized treatments is a common definition of treatment-resistant depression (McIntyre et al., 2014).

Remission was defined as a HAM-D-17 score ≤ 7 at 16 weeks and served as the primary outcome for the study.

Medical Events

Medical events including hospitalizations and emergency department visits were recorded throughout the 16 weeks of the intervention. Participants’ medical records were reviewed at the end of the study to confirm the reported events and assure that no event was overlooked.

Statistical Analyses

Functional data analysis (FDA) (Ramsay et al., 2009) was used to compare the pattern of HR activity from 7:00 pm to 09:00 am for remitters (HAM-D-17 ≤ 7) and non-remitters by plotting and then smoothing the discretized HR data over the measurement interval using B-splines with 9 basis functions (Ramsay et al, 2009). Continuous (i.e., uninterrupted) data during the measurement interval are required for the use of functional data analytic techniques. Although obtaining continuous ECG during standard ambulatory monitoring is difficult to achieve in some cases, FDA has an advantage over standard methods for analyzing ambulatory HR data in that it allows identification of the precise times that the groups differ during a specified time interval. To that end, a permutation test (Ramsay et al, 2009) was used to create a null distribution of between-group differences in HR to evaluate point-wise statistical significance between remitters and non-remitters during the specified interval.

The FDA permutation test does not control for potential confounders, so the mean nighttime heart rate and log of the mean nighttime HRV (lnVLF) aggregated over 12:00 am to 06:00 am were compared between remitted and non-remitted patients in a standard analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Covariates for the adjusted models were chosen à priori and included age, sex, use of beta blockers, antidepressant at baseline, prior MI, body mass index (BMI), and current smoking status.

Chi-square tests and ANOVAs were used to compare the baseline demographic, medical, and depression characteristics of the remitters and non-remitters. Multiple imputation was used to address missing data including post-treatment HAM-D scores (Graham, 2009). All tests were two-tailed with a Type I error rate of 0.05. SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Raleigh, NC) and the FDA library in the R (version 2.15.2) statistical software packages were used to conduct all statistical analyses.

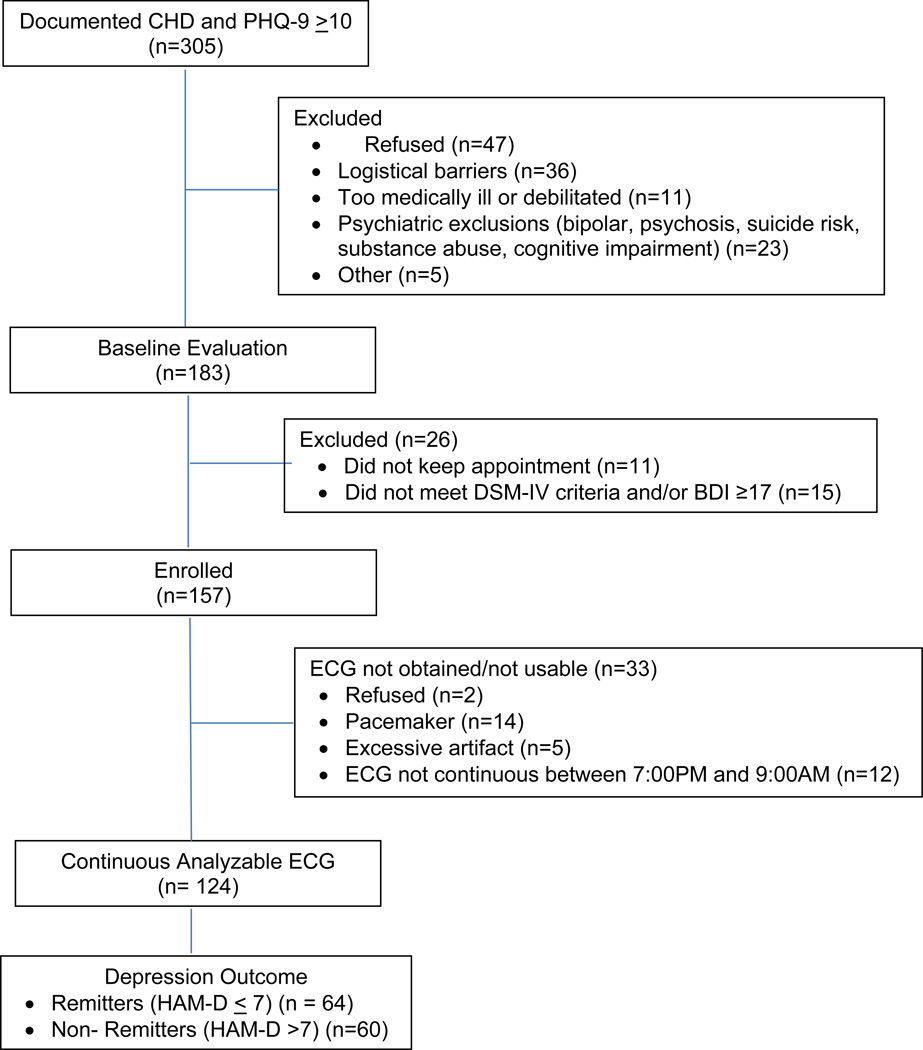

RESULTS

One hundred fifty-seven patients with documented CHD and major depression who provided written informed consent were enrolled in the study. One hundred twenty-four (79%) of the patients had continuous ECG data available between 7:00 PM and 09:00 AM (Figure 1), as required for FDA. The mean baseline HAM-D and BDI-II scores for these participants were 22.9 (SD=5.4) and 30.1 (SD=8.7), and the mean post-treatment scores were 7.7 (SD=6.2) and 8.4 (SD=6.8) respectively. Sixty-four (52%) of the participants with ambulatory ECG data achieved remission as defined as a HAM-D-17 total score <7, and 60 (48%) of the participants did not.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart

HAM-D–17, BDI-2, BAI, and PSQI scores at baseline and at 16 weeks (post-treatment) for the remitters and non-remitters are presented in Table 1. Consistent with the results for the total sample (Carney et al, 2016), non-remitters had higher baseline BDI-2 scores and tended to have higher baseline HAM-D-17 and BAI scores compared to remitters. The groups did not differ on their self-reported hours of sleep per night [remitters, 6.5 (SD=2.0); non-remitters, 6.1 (SD=2.1); p=.20], but the remitters reported significantly higher quality sleep on the PSQI at baseline than did the non-remitters (p=0.0002). Sixty-one percent of the participants who subsequently remitted and 65% of those who did not remit reported having insomnia on most nights prior to beginning treatment (p=.68). Following treatment, the most common residual symptoms among the non-remitters were insomnia (48%) and fatigue (51%), which were present in 12% and 8% of the remitters, respectively.

Table 1.

Depression, anxiety, and sleep quality by post-treatment remission status*

| Assessment | Nonremitters (N=60)* |

Remitters (N=64) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||

| HAM-D-17 total score | |||

| Baseline | 23.8 (SD=5.9) | 22.0 (SD=4.8) | 0.08 |

| 16 weeks | 12.6 (SD=5.8) | 3.1 (SD=4.6) | <0.0001 |

| BDI-2 total score | |||

| Baseline | 32.2 (SD=8.6) | 28.1 (SD=8.3) | 0.009 |

| 16 weeks | 11.4 (SD=6.8) | 5.3 (SD=6.2) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) | |||

| Baseline | 15.5 (SD=8.7) | 12.5 (SD=8.4) | 0.06 |

| 16 weeks | 10.1 (SD=6.8) | 5.5 (SD=6.3) | 0.0002 |

| Sleep Quality | |||

| PSQI Global Score** | |||

| Baseline | 11.7 (SD=3.7) | 9.1 (SD=3.7) | 0.0002 |

| 16 weeks | 9.4 (SD=4.0) | 5.9 (SD=3.6) | <0.0001 |

Continuous variables are reported as Mean (Standard Deviation) (SD). Categorical variables are number of patients (%).

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory Global Score (lower score indicates higher sleep quality)

Major demographic and medical variables are compared between remitters and non-remitters in Table 2. History of MI was more common among the remitters than non-remitters. Medication regimens were stable in most cases during the intervention, with 96% of the participants receiving the same medications at post-treatment as at baseline. There were no differences between groups in either the number of hospitalizations [11 (18%) for remitters vs. 16 (25%) for non-remitters (p=0.37)] or emergency department visits [12 (20%) for remitters vs. 15 (23.4%) for non-remitters (p=0.64)] that occurred during the treatment period.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and medical characteristics by remission status *

| Baseline Characteristic | Nonremitters (N=60) |

Remitters (N=64) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (in years) | 59.5 (SD=9.1) | 60.3 (SD=8.6) | .61 |

| Gender (female) | 28 (46.7) | 24 (37.5) | .30 |

| Race (Caucasian) | 51 (85.0) | 56 (87.5) | .69 |

| Education (12+ years) | 57 (95.0) | 60 (93.8) | .76 |

| Medical | |||

| History of myocardial infarction | 32 (53.3) | 46 (71.9) | .03 |

| History of heart failure | 12 (20.0) | 10 (15.6) | .52 |

| Diabetes | 28 (46.7) | 23 (35.9) | .23 |

| Hypertension | 51 (85.0) | 51 (79.7) | .44 |

| History of CABG | 22 (36.7) | 18 (28.1) | .31 |

| History of PTCA | 44 (74.6) | 50 (78.1) | .64 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 31.0 (SD=5.5) | 32.1 (SD=6.0) | .31 |

| Current Smoker | 15 (25.0) | 16 (25.0) | .99 |

| Sleep Apnea | 13 (22%) | 15 (23%) | .81 |

| New York Heart Association Class | |||

| Asymptomatic | 47 (78.3) | 51 (79.7) | .22 |

| I | 3 (5.0) | 2 (3.1) | |

| II | 10 (16.7) | 7 (10.9) | |

| III | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.3) | |

| Medications | |||

| Statin | 48 (80.0) | 55 (85.9) | .38 |

| Nitrate | 10 (16.7) | 16 (25.0) | .25 |

| Beta blocker | 45 (75.0) | 56 (87.5) | .07 |

| Aspirin | 55 (91.7) | 61 (95.3) | .41 |

| Anxiolytic | 19 (31.7) | 17 (26.6) | .53 |

| SSRI Antidepressant | 32 (53.3) | 29 (45.3) | .37 |

Continuous variables are reported as Mean (Standard Deviation)(SD). Categorical variables represen number of patients (%).

Figure 2 displays the FDA analysis of the continuous HR data comparing HR activity between 7:00 PM and 9:00 AM in remitters and non-remitters. The permutation test (Ramsay et al., 2005) found statistically significant differences in HR activity between the groups over a consecutive interval of nearly five hours: 12:15 AM to 5:00 AM, the interval enclosed by the vertical lines in the figure; p’s range from 0.025 – 0.049 for each 5 minute epoch. One hundred eight (87%) of the participants reported sleeping throughout this time interval, and nearly all reported sleeping during most of it.

Figure 2. Pre-treatment nighttime heart rate patterns for remitted and non-remitted participants.

HR activity between 7:00 pm and 9:00 am in the remitters and non-remitters. HR activity for each 5 minute epoch differed between groups from 12:15 am to 5:00 am (between 1st and 3rd vertical lines)(p’s 0.025 – 0.049). Point of largest difference is at middle vertical line.

Table 3 presents mean baseline 24 hour, daytime and nighttime HRs, and day and nighttime lnVLF power for remitters and non-remitters. HR was significantly higher at night in non-remitters compared to remitters. LnVLF was significantly lower in non-remitters than remitters on all occasions. After covariate adjustment, mean nighttime HR [65.4 (SD=11.1) vs. 69.6 (SD=11.1); F1,116 = 4.38; p=.04] continued to be significantly higher and the adjusted nighttime lnVLF [7.02 (SD=0.81) vs. 6.54 (SD=0.83); F1,108 = 10.24; p=.002] significantly lower in remitters than non-remitters. In order to determine whether nighttime HR and HRV predicts treatment outcome in both patients receiving CBT alone and those receiving CBT plus an antidepressant, a treatment term (CBT alone vs. CBT plus antidepressant) was added to the model along with HR by treatment and HRV by treatment interaction terms. Neither interaction was significant (HR, p=0.97; HRV, p=0.93), suggesting that the predictive value of HR and HRV does not depend on the type of treatment.

Table 3.

Baseline heart rate and heart rate variability by remission status*

| ECG Variable | Nonremitters (N=60) |

Remitters (N=64) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (BPM) | |||

| Mean 24 Hour HR | 74.5 (SD=10.8) | 71.3 (SD=9.4) | .08 |

| Mean Daytime HR | 77.0 (SD=10.8) | 74.3 (SD=10.4) | .16 |

| Mean Nighttime HR | 69.9 (SD=13.2) | 65.1 (SD=9.8) | .03 |

| Heart Rate Variability | |||

| Log Very low frequency (lnVLF) | |||

| 24 hour | 6.55 (SD=0.91) | 6.91 (SD=0.66) | .02 |

| Daytime | 6.49 (SD=0.88) | 6.85 (SD=0.67) | .01 |

| Nighttime | 6.56 (SD=1.11) | 7.00 (SD=0.72) | .01 |

Continuous variables are reported as Mean (Standard Deviation)(SD). Categorical variables represent the number and % of total.

DISCUSSION

Depression has been associated with alterations in certain circadian rhythms including blunted amplitudes of diurnal heart rate, body temperature, plasma cortisol, and thyroid stimulating hormone (Bhattacharyya et al., 2008; Souetre et al., 1989), as well as attenuated circadian patterns of gene expression in the brain (Li et al., 2013). Altered circadian rhythms associated with non-restorative sleep have been associated with treatment-resistant or persistent depression (Buysse et al, 1999; Roest et al., 2012; Szuba et al, 2001).

Consistent with the study hypotheses, patients with stable CHD and major depressive disorder whose depression failed to remit following aggressive treatment had higher pre-treatment nighttime HRs than did patients whose depression subsequently remitted. Non-remitters also had lower nighttime and daytime lnVLF and reported poorer quality of sleep before they received treatment than did those patients whose depression remitted. We previously reported the relationship between specific pre-treatment medical factors and depression outcomes in these patients (Carney et al, 2016). Only the level of free T4 thyroid hormone predicted treatment outcome; markers of inflammation (CRP, TNF, IL-6) and physical activity did not. Although thyroid hormone affects HR, the association between nighttime HR and treatment response in this study was not explained by free T4 levels.

VLF power reflects changes in heart rate at a cycle length of 20 seconds to 5 minutes. There is evidence that VLF power reflects not only cardiovascular autonomic modulation, but also thermoregulatory activity and blood pressure modulation by the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. However, studies evaluating the relative contributions of these systems have found that the dominant determinant of VLF power is the parasympathetic nervous system (Taylor et al., 1998).

In healthy, non-depressed patients, HR and blood pressure decrease significantly during the night due to parasympathetic predominance during sleep. We recently found that an elevated nighttime HR in depressed post-MI patients predicted mortality in the months after the acute event (Carney et al, 2014). An attenuated decrease in BP at night in patients with established CHD has also been associated with excessive morbidity and mortality (Ingelsson et al., 2006; Staessen et al., 1999). Thus, high nocturnal HR associated with a lack of parasympathetic predominance at night may explain the increased mortality associated with poor response to depression treatment.

Following depression treatment, nearly half of the non-remitters continued to report insomnia, which was the second most common residual symptom after fatigue in these patients. These two symptoms have been shown in previous studies to be among the most common residual symptoms following depression treatment, and they are strong predictors of relapse and recurrence (Conradi et al., 2011). Higher rates of relapse and recurrence may contribute to the high risk for mortality in patients with CHD who do not respond to depression treatment.

Because insomnia and non-restorative sleep are commonly associated with depression and other psychiatric disorders, and because these symptoms often persist after depression has been treated, it might be necessary to augment depression treatments in order to address residual insomnia. A meta-analysis of CBT interventions for insomnia in patients with other psychiatric or medical disorders found that it was associated with greater than three-fold likelihood of remission compared to control conditions (Wu et al., 2015). Moreover, the CBT intervention also had positive effects on the comorbid conditions, suggesting that insomnia may add to or worsen the symptoms reported for other disorders. Future studies of depression treatment in patients with CHD should evaluate the effectiveness of adjunctive CBT for insomnia.

Remitters and non-remitters reported sleeping about the same number of hours, suggesting that it is the quality and not the quantity of sleep that may be important, although self-report of sleep time is often unreliable (Fernandez-Mendoza et al., 2011). In a previous study we found that undetected sleep apnea predicted poor response to depression treatment in a group of medically stable patients with CHD (Roest et al, 2012), but in the present study, diagnosed cases of sleep apnea did not differ between groups. Most of the patients in this study who had sleep apnea were regularly using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices, which may explain why sleep apnea did not predict response to depression treatment in this sample.

The participants in this trial received up to two treatments (CBT and antidepressant medication) that have been shown to be safe and effective in patients with CHD. The intervention was similar to the one that was used in the ENRICHD clinical trial, which was the first to show a relationship between improvement in depression following treatment and improved survival (Carney et al, 2004). Other clinical trials have also shown a relationship between improvement in depression and improvement in survival using different treatments for depression, including CBT, exercise training, sertraline, mirtazapine, and citalopram (Carney et al, 2009). Thus, improved survival in treatment responders does not seem to be dependent on the specific depression treatments that patients receive.

Limitations

There are limitations of the present study that need to be recognized. First, we used an artificially dichotomized (remission) rather than a continuous variable to determine the relationship between nighttime HR and treatment response. However, patients with CHD who have even a few symptoms of depression are at increased risk for mortality and medical morbidity (Bush et al., 2001), which makes treating to remission especially important in these patients. Thus, we chose the dichotomous variable of remission, the goal of treatment, as the primary outcome.

It is possible that some patients who did not respond favourably to treatment would have responded to more sessions of CBT or to higher doses of sertraline. However, patients were offered up to 12 sessions of CBT with telephone contacts as needed during this time. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that higher doses of sertraline (150–200mgs) only marginally increase the response rate while significantly increasing adverse side-effects and dropouts (Fabre et al, 1995; Schweizer et al, 2001).

Polysomnography would have provided information about objective sleep characteristics and sleep disorders, including sleep-disordered breathing. We relied instead on the self-report of the participants as to when they were sleeping and rating the subjective quality of their sleep.

Some of the participants recruited for this study did not receive ambulatory ECG monitoring, including those with pacemakers, and others could not be included because of excessive artifact or ectopic beats. Additionally, some patients had to be excluded due to the requirement in FDA analysis to have continuous ECG data for the time interval of interest. Thus, these results may not apply to all patients with depression and CHD.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Further Research

In conclusion, patients with stable CHD and major depressive disorder whose depression failed to remit despite aggressive treatment had higher pre-treatment nighttime HR, lower daytime and nighttime HRV, and reported poorer sleep quality than patients whose depression subsequently remitted. These findings may help explain why patients with CHD who do not respond to treatment are at higher risk for mortality. Future studies should investigate the characteristics of disordered sleep in these patients, and attempt to identify appropriate treatments to augment standard treatments for depression as needed. If CBT or other treatments for insomnia and related sleep disorders can improve sleep, lower nighttime HR, and increase HRV in depressed patients with CHD, then studies will be needed to determine whether effectively treating depression and disordered sleep improves survival in these patients.

Highlights.

Fifty two % of heart patients with major depression remitted with treatment.

High nighttime heart rate and low heart rate variability predicted remission.

Insomnia and fatigue were most common residual symptoms in nonremitters.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Patricia Herzing, RN; Iris Csik, ACSW; Jessica McDaniel, MA; Carol Sparks, LPN; and Kimberly Metze, BS for their contributions to the study.

Role of Funding Source, and Author Participation:

This research study was supported by Grant Number R01HL089336 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. The funding agency was not directly involved in the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to both the research study and to the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- BAI

Beck Depression Anxiety Inventory

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory 2

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- CBT

cognitive behavior therapy

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- FDA

functional data analysis

- HAM-D-17

Hamilton Depression Inventory-17 items

- HRV

heart rate variability

- lnVLF

log of Very Low Frequency

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- SSRI

Selective Serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Carney or a member of his family owns stock in Pfizer, Inc. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions to the Study

Robert M. Carney, PhD Principal Investigator: participated in all phases of the study design and implementation, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in drafting the manuscript.

Kenneth E. Freedland, PhD Co-investigator: participated in all phases of study design and implementation, in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Brian C. Steinmeyer, MS Statistician/co-investigator: participated in study design, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Eugene H. Rubin, MD, PhD Psychiatrist/co-investigator: participated in the study design and implementation, the interpretation of the data, and in revising the manuscript.

Phyllis K. Stein, PhD: Electrophysiologist/co-investigator, participated in all phases of the study design and implementation, in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in revising the manuscript.

Michael W. Rich, MD: Cardiologist/co-investigator, participated in all phases of study design and implementation, in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the revising the manuscript.

References

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II Manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya MR, Molloy GJ, Steptoe A. Depression is associated with flatter cortisol rhythms in patients with coronary artery disease. J Psychosom. Res. 2008;65(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC, Tayback M, Richter D, Stevens S, Zahalsky H, Fauerbach JA. Even minimal symptoms of depression increase mortality risk after acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001;88(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Hall M, Tu XM, Land S, Houck PR, Cherry CR, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Latent structure of EEG sleep variables in depressed and control subjects: descriptions and clinical correlates. Psychiatry Res. 1998;79(2):105–122. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Tu XM, Cherry CR, Begley AE, Kowalski J, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Pretreatment REM sleep and subjective sleep quality distinguish depressed psychotherapy remitters and nonremitters. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;45(2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Stein PK, Howells WB, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Hayano J, Domitrovich PP, Jaffe AS. Low heart rate variability and the effect of depression on post-myocardial infarction mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005a;165(13):1486–1491. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Youngblood M, Veith RC, Burg MM, Cornell C, Saab PG, Kaufmann PG, Czajkowski SM, Jaffe AS. Depression and late mortality after myocardial infarction in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study. Psychosom. Med. 2004;66(4):466–474. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000133362.75075.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Stein PK, Watkins L, Catellier D, Berkman LF, Czajkowski SM, O’Connor C, Stone PH, Freedland KE. Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(17):2024–2028. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Freedland KE. Treatment-resistant depression and mortality after acute coronary syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):410–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Freedland KE, Steinmeyer B, Rubin EH, Mann DL, Rich MW. Cardiac risk markers and response to depression treatment in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom. Med. 2016;78(1):49–59. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC. Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom. Med. 2005b;(67 Suppl 1):S29–S33. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000162254.61556.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Steinmeyer B, Freedland KE, Blumenthal JA, Stein PK, Steinhoff WA, Howells WB, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Domitrovich PP, Burg MM, Hayano J, Jaffe AS. Nighttime heart rate and survival in depressed patients post acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom. Med. 2008;70(7):757–763. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181835ca3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Steinmeyer B, Freedland KE, Stein PK, Hayano J, Blumenthal JA, Jaffe AS. Nocturnal patterns of heart rate and the risk of mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2014;168(1):117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradi HJ, Ormel J, de JP. Presence of individual (residual) symptoms during depressive episodes and periods of remission: a 3-year prospective study. Psychol. Med. 2011;41(6):1165–1174. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre LF, Abuzzahab FS, Amin M, Claghorn JL, Mendels J, Petrie WM, Dube S, Small JG. Sertraline safety and efficacy in major depression: a double-blind fixed-dose comparison with placebo. Biol. Psychiatry. 1995;38(9):592–602. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Mendoza J, Calhoun SL, Bixler EO, Karataraki M, Liao D, Vela-Bueno A, Jose Ramos-Platon M, Sauder KA, Basta M, Vgontzas AN. Sleep misperception and chronic insomnia in the general population: role of objective sleep duration and psychological profiles. Psychosom. Med. 2011;73(1):88–97. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181fe365a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedland KE, Skala JA, Carney RM, Raczynski JM, Taylor CB, Mendes de Leon CF, Ironson G, Youngblood ME, Krishnan KR, Veith RC. The Depression Interview and Structured Hamilton (DISH): rationale, development, characteristics, and clinical validity. Psychosom. Med. 2002;64(6):897–905. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000028826.64279.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelsson E, Bjorklund-Bodegard K, Lind L, Arnlov J, Sundstrom J. Diurnal blood pressure pattern and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2859–2866. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Gray MA, Felmingham KL, Brown K, Gatt JM. Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: a review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugsand LE, Vatten LJ, Platou C, Janszky I. Insomnia and the risk of acute myocardial infarction: a population study. Circulation. 2011;124(19):2073–2081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.025858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JZ, Bunney BG, Meng F, Hagenauer MH, Walsh DM, Vawter MP, Evans SJ, Choudary PV, Cartagena P, Barchas JD, Schatzberg AF, Jones EG, Myers RM, Watson SJ, Jr, Akil H, Bunney WE. Circadian patterns of gene expression in the human brain and disruption in major depressive disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110(24):9950–9955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305814110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS, Leifheit-Limson EC, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Wulsin L. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2014;129(12):1350–1369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Filteau MJ, Martin L, Patry S, Carvalho A, Cha DS, Barakat M, Miguelez M. Treatment-resistant depression: Definitions, review of the evidence, and algorithmic approach. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;156:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JO, Hooker G, Graves S. Functional data analysis with R and MATLAB. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JO, Silverman BW. Functional data analysis. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roest AM, Carney RM, Stein PK, Freedland KE, Meyer H, Steinmeyer BC, de Jonge P, Rubin EH. Obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome and poor response to sertraline in patients with coronary heart disease. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):31–36. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottman JN, Steinman RC, Albrecht P, Bigger JT, Jr, Rolnitzky LM, Fleiss JL. Efficient estimation of the heart period power spectrum suitable for physiologic or pharmacologic studies. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990;66(20):1522–1524. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90551-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer E, Rynn M, Mandos LA, Demartinis N, Garcia-Espana F, Rickels K. The antidepressant effect of sertraline is not enhanced by dose titration: results from an outpatient clinical trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(3):137–143. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souetre E, Salvati E, Belugou JL, Pringuey D, Candito M, Krebs B, Ardisson JL, Darcourt G. Circadian rhythms in depression and recovery: evidence for blunted amplitude as the main chronobiological abnormality. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(3):263–278. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staessen JA, Thijs L, Fagard R, O’Brien ET, Clement D, de Leeuw PW, Mancia G, Nachev C, Palatini P, Parati G, Tuomilehto J, Webster J. Predicting cardiovascular risk using conventional vs ambulatory blood pressure in older patients with systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. JAMA. 1999;282(6):539–546. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer HG. The relationship between psychiatric illness and the circadian pattern of heart rate. Aust. N. Z. J Psychiatry. 1998;32(2):187–198. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuba MP, Fernando AT, Groh-Szuba G. Sleep abnormalities in treatment-resistant mood disorders. In: Amsterdam JD, Hornig M, Nierenberg AA, editors. Treatment-resistant mood disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Taillard J, Sanchez P, Lemoine P, Mouret J. Heart rate circadian rhythm as a biological marker of desynchronization in major depression: a methodological and preliminary report. Chronobiol. Int. 1990;7(4):305–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Carr DL, Myers CW, Eckberg DL. Mechanisms underlying very-low-frequency RR-interval oscillations in humans. Circulation. 1998;98(6):547–555. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JQ, Appleman ER, Salazar RD, Ong JC. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Comorbid With Psychiatric and Medical Conditions: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015;175(9):1461–1472. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]