Abstract

Objective

To present the preliminary results from treating patients with Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease (LCPD) by means of hip arthrodiastasis using a monolateral external fixator applied to the hip and to succinctly describe the surgical technique used, in a prospective study.

Methods

Prospective study on 18 patients with LCPD who underwent surgical treatment by means of the hip arthrodiastasis technique using a monolateral external fixator. There were 13 male and five female patients of mean age 8.5 years, ranging from five to 13 years. All the patients presented unilateral hip impairment: nine on the right side and nine on the left. The results were evaluated at maturity using clinical and radiological criteria.

Results

All the patients evolved with improvement of joint mobility, and pain relief was achieved in 88.9% of them. Reossification of the femoral epiphysis occurred within the first three months of the treatment. The hips operated at the necrosis stage of the disease did not passed through the fragmentation stage, thus shortening the evolution of the disease. The results were 77.8% satisfactory and 22.2% unsatisfactory.

Conclusion

Hip arthrodiastasis with a monolateral external fixator during the active phase of LCPD improved the degree of joint mobility. Use of the arthrodiastasis technique at the necrosis stage or at the fragmentation stage (active phase of the disease) presented satisfactory results from treatment of LCPD.

Keywords: Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, Orthopedic procedures, External fixators, Hip joint

Resumo

Objetivo

Apresentar os resultados preliminares do tratamento da DLCP com o uso de artrodiástase com fixador externo monolateral aplicado ao quadril e descrever sucintamente a técnica operatória usada em um estudo prospectivo.

Métodos

Estudo prospectivo de 18 pacientes com DLCP submetidos ao tratamento operatório com a técnica de artrodiástase do quadril por meio de fixador externo unilateral. São 13 pacientes do gênero masculino e cinco do feminino com idade média de 8,5 anos com variação de cinco a 13 anos. Todos os pacientes com acometimento unilateral do quadril, nove à direita e nove à esquerda. A avaliação dos resultados foi feita na maturidade e considerou critérios clínicos e radiográficos.

Resultados

Todos os pacientes evoluíram com melhoria da mobilidade articular com alívio da dor obtido em 88,9% dos pacientes. A reossificação da epífise femoral ocorreu nos primeiros três meses do tratamento. Os quadris operados na fase de necrose não passaram pela fase de fragmentação e abreviaram o tempo de evolução da doença. Os resultados foram 77,8% satisfatórios e 22,2% insatisfatórios.

Conclusões

A artrodiástase do quadril com fixador externo monolateral na fase ativa da DLCP melhora o grau de mobilidade articular. O emprego da técnica de artrodiástase nas fases de necrose e fragmentação (fase ativa da doença) apresenta resultados satisfatórios no tratamento da DLCP.

Palavras-chave: Doença de Legg-Calve-Perthes, Procedimentos ortopédicos, Fixadores externos, Articulação do quadril

Introduction

A childhood hip disorder was described simultaneously in 1910 by Legg (United States), Calvé (France), and Perthes (Germany) as an obscure alteration, pseudocoxalgia, and juvenile deforming arthritis, which characterize the picture known today as Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCPD).1

The disease is self-limiting, originated by ischemia of the femoral head in varying grades, leading to bone necrosis. The etiology is still unknown, although several hypotheses that attempt to explain the deficiency in blood supply of the femoral head have been raised.2

There are various degrees of avascular necrosis in LCPD, which depend mainly on the extent of the injury. The presence of new episodes of ischemia, likely to occur during the course of the disease, may result in a femoral head with different stages of self-repair.3

Initially, necrosis affects the epiphyseal tissue and give rise to newly formed bone tissue. The hyaline cartilage becomes relatively thickened, as it continues to receive normal nutrition from the synovial fluid and maintains the spherical shape of the femoral head.4

In the second stage of the disease, there is fragmentation of the femoral head, followed by resorption and bone replacement, which lasts from one to three years. In this stage, there is a spread of necrotic tissue by vascularized connective tissue; resorption and necrosis when replacement by immature bone tissue takes place. The epiphysis loses height due to the collapse of the trabecular bone and the absorption of fragmented bone. In moderate and severe cases, metaphyseal changes in the femoral neck take place.

The third stage of the disease, the repairing stage, is characterized by the replacement of necrotic and immature bone by mature bone tissue. The histopathological pattern observed in this stage ranges from areas without bone infarction to femoral heads with several areas of necrotic and mature bone.

The child with LCPD feels pain in the hip and/or knee and decreased joint range of motion, primarily in the internal rotation and hip abduction movements.

Radiographic examination in LCPD is characterized by three signs: first is the shrinking of the ossification nucleus of the femoral head, with widening of the joint space; second is a subchondral fracture (Caffey's sign), which, according to Salter and Thompson,3 marks the beginning of the clinical symptoms and is considered, depending on its length, a prognostic factor for disease; third sign is the increase of the radiopacity of the femoral head, characterizing avascular necrosis. From that moment on, the repair process produces heterogeneous images, depending on the areas of revascularization and new necrosis outbreaks.

The objectives of orthopedic LCPD treatment are pain relief, the containment of the femoral head in the acetabulum, and the recovery of joint range of motion in the affected hip. Treatment methods commonly used to achieve these targets are traction, load restriction, tenomyotomy, abduction orthosis, and osteotomies at both the proximal femur and the acetabulum.

Treatment results are influenced by many factors; main ones are age at onset, maintenance of the joint mobility, and degree of hip involvement.

The long-term follow-up of patients treated in this hospital – with abduction devices, femoral and iliac osteotomies, or cheilectomy – has indicated a tendency toward remodeling, with alterations in the sphericity of the femoral head.5, 6, 7

The treatment of LCPD has as its basic principle the protection of the proximal femoral epiphysis. The idea of a treatment method that allows centering of the femoral head and provides protection against mechanical body load and against the action of pelvitrochanteric muscles is attractive.

In this article, the authors present the preliminary results of LCPD treatment with the use of unilateral external fixator through arthrodiastasis, aiming to create negative pressure on the femoral head and preserving the joint space, in an attempt to decrease the harmful effects of subchondral fractures and destruction of the trabecular bone of the femoral head.

Material and methods

This prospective study reports the initial experience with 18 patients with LCPD submitted to surgery with the hip arthrodiastasis technique through the use of a unilateral external fixator.

This study was approved by the Scientific Committee and Research Ethics Committee of our institution (Document No. 201/95).

Thirteen males and five females, with a mean of 8.5 years of age (range: 5–13 years), were included.

All patients had unilateral hip involvement: nine at the left and nine at the right side.

Patients were classified according to the radiographic criteria developed by Catterall8 and by Herring et al.9

Results were assessed considering clinical and radiographic criteria. As clinical criteria, the response of patients in relation to pain control in the hip joint of the affected side were assessed, as well as joint range of motion and general degree of movement of the hip: external and internal rotation, abduction and adduction, flexion and extension.

Radiographic evaluation included the initial Catterall8 and Herring et al.9 classification, as well as the classification for the final results proposed by Stulberg et al.10 at skeletal maturity of the hip region. The center-edge (CE) angle of the acetabulum was also measured. The sphericity of the femoral head was assessed according to the Mose11 method, and the indexes and epiphyseal quotient were measured. The extent of hip subluxation was also assessed.

The system proposed by the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA),12 shown in Table 1, was used for the evaluation of postoperative results of patients.

Table 1.

Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North-America (POSNA) assessment system.12

| Result | Center-edge angle | Mose circles |

|---|---|---|

| Good | >20° | 0 |

| Fair | 15–19° | 2 |

| Poor | <15° | >2 |

Inclusion criteria

Patients of both genders, with the diagnostic of LCPD, with unilateral hip disease presenting restriction of the affected joint movements, and pain during activities of daily living were included. Types III or IV in the Catterall8 classification and with two or more “radiographic risk signs”; types B or C in the classification by Herring et al.9; patients in the early stages of radiographic condition, i.e., condensation or fragmentation, which characterizes the “active” stage of the disease were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with bilateral involvement of the hips and whose radiographic examination presented initial subluxation above 50% of the femoral head circumference measured by the Dickens and Menelaus13 method, as well as patients in the stage of femoral head remodeling according to radiographic analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of quantitative ordinal parameters of age, time of usage of the external fixator, follow-up time, and range of motion (external and internal rotation, abduction and adduction, flexion and extension) were calculated: mean (M), standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), maximum (Max) and minimum values (Min), and the number of cases (N). In the comparison of two groups of dependent paired ordinal parameters, the paired t-test was used, in case of parametric distributions, and the Wilcoxon test, in case of non-parametric distributions. Mann–Whitney's U test was used for independent non-parametric samples. Absolute and relative frequency distribution (%) was calculated to describe normal distributions (qualitative). Comparisons between nominal distributions were made using Fisher's exact test.

The significance level of 5% (α = 0.05) was adopted. Significant results (differences) were highlighted by asterisks.

Surgical technique

Indications for surgical treatment with hip arthrodiastasis through external fixation in LCPD were as follows:

-

1)

Pain, even in the lowest degree;

-

2)

Decrease in the degree of mobility of the affected joint;

-

3)

Catterall groups III or IV;

-

4)

At least two radiographic signs of “head at risk”;

-

5)

Less than 50% subluxation of the femoral head.

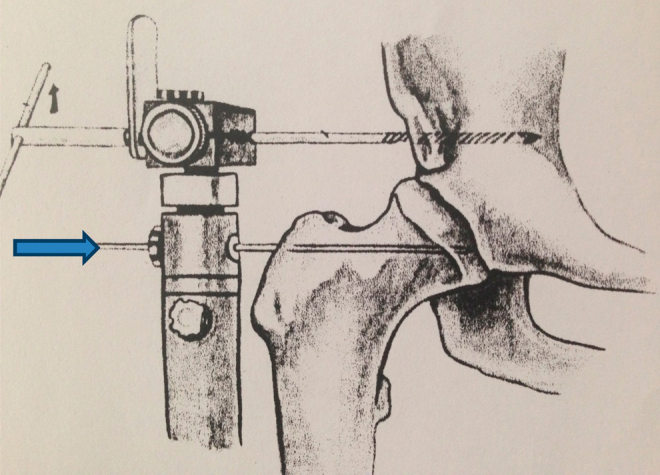

The patient is operated using a conventional fluoroscopic table to allow image intensifier assistance. Percutaneous tenotomy of the hip adductors was routinely performed. A unilateral, articulated external fixator (Impolfix®, Impol, São Paulo, Brazil) was used. The external fixator is applied with a couple of Schanz screws positioned in the acetabular region and another couple of Schanz screws in the diaphyseal zone of the femur.

Joint diastasis is applied during surgery aiming to correct Shenton's line under fluoroscopic control.

Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 illustrate the main steps for positioning the unilateral external fixator.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the position of the external fixator. Two to three Schanz screws posteriorly and inferiorly. (Impolfix®, Impol, São Paulo, Brazil).

Source: Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, FMUSP.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the position of the external fixator from the rotation center of the femoral head (arrow). (Impolfix®, Impol, São Paulo, Brazil).

Source: Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, FMUSP.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the position of the external fixator (Impolfix®, Impol, São Paulo, Brazil) and how arthrodiastasis is performed.

Source: Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, FMUSP.

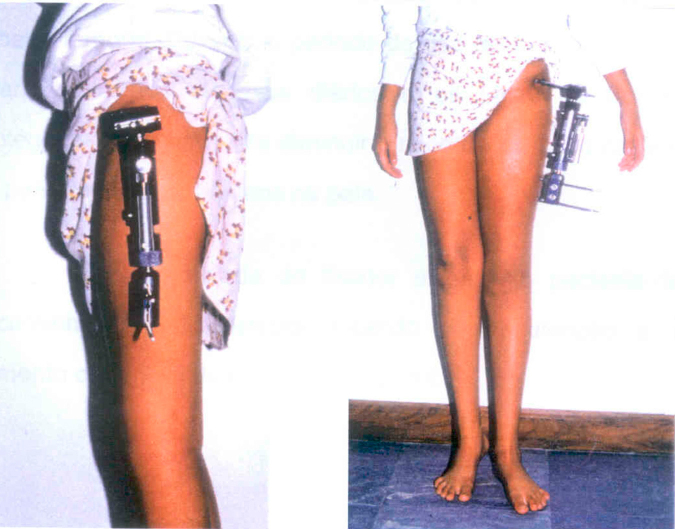

Fig. 4.

Photograph of the ideal positioning of monolateral external fixator (Impolfix®, Impol, São Paulo, Brazil).

Source: Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, FMUSP.

Postoperative

If hip diastasis is not achieved through surgery, it can be slowly progressed during postoperative period of 10–15 days. Weekly dressings are used in the areas of cutaneous emergence of the Schanz screws. Control X-rays are performed at four-week intervals. The external fixator remains inserted for approximately three months.

Results

Clinical analysis

The assessment of age, sex (male and female), and the affected side (right or left) of the patients is shown in Table 2. Table 3 presents the pre- and postoperative clinical analysis of the degree of hip amplitude.

Table 2.

Presentation of patients according to age (years), sex, and affected side.

| Order | Age (years) | Sex | Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | M | R |

| 2 | 12 | M | L |

| 3 | 9 | M | L |

| 4 | 9 | F | L |

| 5 | 9 | M | L |

| 6 | 13 | M | R |

| 7 | 6 | F | R |

| 8 | 9 | M | R |

| 9 | 8 | M | L |

| 10 | 10 | M | L |

| 11 | 7 | M | R |

| 12 | 8 | M | L |

| 13 | 9 | M | L |

| 14 | 10 | M | R |

| 15 | 7 | F | R |

| 16 | 9 | F | R |

| 17 | 5 | F | R |

| 18 | 5 | M | L |

M, males (13); F, females (5); R, right (9); L, left (9).

Age – mean of 8.5 years; <7 years = 16.7%; >7 years = 83.3%.

Table 3.

Degree of range of motion of the hip, pre- and postoperative, with statistical analysis.

| Amplitude (°) | Preoperative | Postoperative | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abduction | 20.6 ± 11.49 (2.71) | 40.3 ± 9.1 (2.1) | Wilcoxon Tc = 34 To = 0 |

| Adduction | 16.9 ± 5.18 (1.22) | 20.8 ± 4.62 (1.09) | Wilcoxon Tc = 2 To = 0 |

| Flexion | 92.2 ± 0.17 (0.04) | 115.5 ± 11.99 (2.83) |

tPAIRED t = 4.73 p = 0.0002 |

| Extension | 16.4 ± 2.87 (0.68) | 19.2 ± 2.57 (0.61) |

tPAIRED t = 4.61 p = 0.0002 |

| External rotation | 16.9 ± 11.65 (2.75) | 37.5 ± 11.41 (2.69) | Wilcoxon Tc = 40 To = 1 |

| Internal rotation | 9.3 ± 9.54 (2.25) | 25.6 ± 12.23 (2.88) | Wilcoxon Tc = 29 To = 1 |

Tc, critical T; To, T obtained.

Radiographic analysis

Preoperative results (initial) according to Catterall and Herring classifications are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

LCPD staging and frequency distribution of the results according to the Catterall and Herring classifications.

| Classification | Catterall | Herring |

|---|---|---|

| III – 7 (38.9%) | A – 1 (5.6%) | |

| IV – 11 (61.1%) | B – 12 (66.7%) | |

| C – 5 (27.8%) | ||

| Total | 18 (100%) | 18 (100%) |

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 present the studies comparing the outcomes after surgery for POSNA criteria and the following factors: sex, age, and final result.

Table 5.

Frequency distribution of the postoperative results in the POSNA classification of according to sex. Comparison by Fisher's exact test (α = 0.05).

| POSNA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Satisfactory | Unsatisfactory | Total |

| Male | 11 (61.1%) | 2 (11.1%) | 13 (72.2%) |

| Female | 3 (17.7%) | 2 (11.2%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Total | 14 (77.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | 18 (100%) |

Fisher p = 0.30.

Table 6.

Frequency distribution of the postoperative results in the POSNA classification of according to age range. Comparison by Fisher's exact test (α = 0.05).

| POSNA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (years) | Satisfactory | Unsatisfactory | Total |

| <7 | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.5%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| ≥7 | 12 (66.7%) | 3 (16.7%) | 15 (83.3%) |

| Total | 18 (100%) | 4 (22.2%) | 18 (100%) |

Fisher p = 0.30.

Table 7.

Frequency distribution of the postoperative results in the POSNA classification.

| POSNA rating | Absolute | Relative (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfactory | 14 | 77.8 |

| Unsatisfactory | 4 | 22.2 |

| Total | 18 | 100.0 |

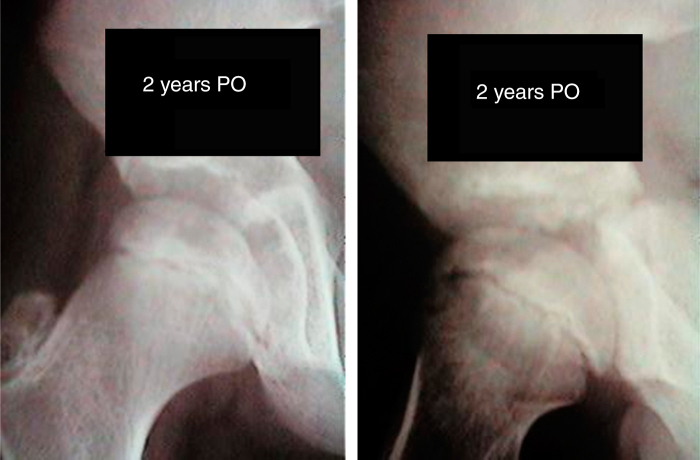

Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8 show the evolution of a patient operated at 7 years and 4 months and the progress two years after surgery.

Fig. 5.

Male patient, 7 years and 4 months, Catterall III. Preoperative image.

Fig. 6.

Patient from Fig. 1, at one and two months postoperatively. Newly growing tissue (arrow).

Fig. 7.

Patient from Fig. 1, at three months postoperatively. Reossification of the femoral head.

Fig. 8.

Patient from Fig. 1, at two years postoperatively.

Discussion

LCPD is a self-limiting condition caused by ischemia and varying degrees of femoral head necrosis. The cause of ischemia is currently unknown; many hypotheses are suggested, but there is still no complete proof. Currently, the most accepted theories are delay in skeletal development, microtrauma, and vascular alterations.14

According to Bensahel,15 the highest frequency of LCPD is observed in the range of 4–8 years; it is an rare diagnosis outside the age range of 2–10 years. In the present study, the mean age at disease onset was 8.5 years, ranging from 5 to 13. This group of patients can be considered a poor prognostic risk group, as age at disease onset is one of the factors that most influence outcomes.16, 17, 18

The present study included patients classified as Catterall types III and IV, which are the two groups with worst prognosis. Furthermore, patients had at least two radiographic signs of “head at risk.” Considering the limitation of (mean) movement amplitude of the affected hip, the need for surgical treatment indication for the group of patients studied was proven.

In the surgical treatment of LCPD, varization osteotomies of the femur or the iliac bone (acetabulum) are the surgical treatment modalities most used to achieve femoral head containment. The literature review retrieved studies that showed no significant difference between both types of osteotomy.19, 20

The maintenance of movement while the joint is subjected to a traction force with external fixator was described by Volkov and Oganesian.21 The use of an external fixator to promote the maintenance of the joint space, utilized in various joints such as knee, elbow, hip, and ankle, has also been described for various orthopedic conditions, such as trauma and sequelae, septic arthritis, tuberculosis, epiphysiolysis, chondrolysis, and LCDP.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 According to van Valburg et al.,26 the maintenance of the joint space provided by the external fixator, even after a short period of treatment, indicates some joint repair, an important factor for obtaining clinical improvement of the patient.

The hip arthrodiastasis generated by LCPD enables the maintenance of the joint space, a optimal situation for treatment. The ischemic femoral head is subjected to pressure overload even when the patient is at rest, due to the action of the muscles. The idea of achieving neutralization of the muscle strength and of the weight force acting on the femoral head, which increases the joint space, creating a situation in which the articular cartilage can regenerate after injury, is very attractive. Adding movement to the method allows for an improvement in synovial fluid circulation and consequent improvement of articular cartilage nutrition, giving the method very useful mechanical and biological characteristics for the treatment of LCPD. Moreover, this technique preserves the articular surface and protects the epiphysis from forces acting on the hip; it also reduces the risk of flattening of the head and collapse of the newly formed vessels. According to Stulberg,10 decreased joint space is the factor that shows the greatest association with clinical long-term results in LCPD.

During the natural course of LCPD, the hip undergoes the phases of synovitis, necrosis, and remodeling4; arthrodiastasis was used on hips in the necrosis or fragmentation stages (“active” stages of the disease). A fast revascularization of the femoral epiphysis was observed in an interval of one to three months (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8). When hips were treated in the necrosis stage, regeneration occurred without the fragmentation phase. This phenomenon is consistent with that described by Volpon et al.27

All modalities of treatment for LCPD are based in mechanical concepts. Arthrodiastasis offers a biological concept beyond the mechanical concept of anatomical joint centralization and mechanical load protection imposed on the joint.28, 29, 30 According to the concepts of Ilizarov,31 arthrodiastasis induces angiogenesis around the entire joint. It is important to note that, under the influence of mechanical traction-load offered by arthrodiastasis, active histogenesis occurs not only in the bone, but also in the regional soft tissues; yet, according to Ilizarov, the process of tissue formation and growth in an adult organism has many features in common with tissue formation during the embryonic and immediate postnatal periods. Fig. 6, Fig. 7 present an example of this type of tissue formation.

The preliminary satisfactory results of treatment with arthrodiastasis obtained in 77.8% of patients can be considered as overall “good,” thus accrediting the technique as an effective LCPD treatment method.

The authors agree with Kucukkaya et al.32 that arthrodiastasis is a good operative treatment technique for patients aged above 6 years and considered as having poor prognosis in the criteria set forth by Catterall. Moreover, the process of reossification/remodeling of the femoral head appears to be shortened by arthrodiastasis of the affected hip.

Conclusion

Hip arthrodiastasis with unilateral external fixator in the active stages of LCPD improves the degree of joint mobility.

The use of the arthrodiastasis technique in the necrosis and fragmentation stages (active stages of the disease) presents satisfactory results in the treatment of LCPD.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Discipline of Pediatric, Department of Orthopedy and Traumatology, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Wenger D.R., Ward T.W., Herring J.A. Current concepts review in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(5):778–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim H.K.W. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):676–686. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salter R.B., Thompson G.H. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. The prognostic significance of the subchondral fracture and a two-group classification of the femoral head involvement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(4):479–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsäter S. Coxa plana. A histo-pathologic and arthrographic study. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1953;12:5–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordeiro E.N. Femoral osteotomy in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(150):69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarniero R., Ishikawa M.T., Luzo C.A.M., Monetenegro N.B., Godoy Júnior R.M. Resultados da osteotomia femoral varizante no tratamento da doença de Legg-Calvé-Perthes. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 1997;52(3):132–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarniero R., Luzo C.A.M., Grigoletto W., Jr., Lage L.A.A., Iacovone M. Cheilectomy as a salvage surgery in the diseased hip: early results. MAPFRE Med. 1995;6:208–210. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catterall A. The natural history of Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53(1):37–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herring J.A., Neustatdt J.B., Willians J.J., Browne R.H. The lateral pillar classification of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12(2):143–150. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stulberg S.D., Cooperman D.R., Wallenstein R. The natural history of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;63(7):1095–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mose K. Methods of measuring in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(150):103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meehan P.L., Angel D., Nelson J.M. The Scottish Rite abduction orthosis for the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease. A radiographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;79(1):2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickens D.R.V., Menelaus M.B. The assessment of the prognosis in Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60(2):189–194. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.60B2.659461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimeglio A. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: etiology. MAPFRE Med. 1995;6:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensahel H. Epidemiology of LCP disease. MAPFRE Med. 1995;6:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herring J.A. The treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(3):448–457. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poussa M., Yrjonen T., Hoikka V., Ostermam K. Prognosis after conservative and operative treatment in Perthes’ disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(297):82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoikka V., Poussa M., Yrjonen T., Ostermam K. Intertrochanteric varus osteotomy for Perthes’ disease. Radiographic changes after 2–16 year follow-up of 126 hips. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62(6):549–553. doi: 10.3109/17453679108994494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moberg A., Hansson G., Kaniklides C. Results after femoral and innominate osteotomy in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(334):257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sponseller P.D., Desai S.S., Millis M.B. Comparison of femoral and innominate osteotomies for the treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1131–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkov M.V., Oganesian O.V. Restoration of function in the knee and elbow with a hinge-distractor apparatus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(5):591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krumins M., Kalnis J., Lacis G. Reconstruction of the proximal end of the femur after hematogenous osteomyelitis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13(1):63–67. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canadell J., Gonzales F., Barrios R.H., Camillo S. Arthrodiastasis for stiff hips in young patients. Int Orthop. 1993;17(4):254–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00194191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judet R., Judet T. Arthrolyse et arthroplastie sous distracteur articulaire. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1978;64(5):353–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cobb T.K., Morrey B.F. Use of distraction arthroplasty in unstable fracture dislocations of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(312):201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Valburg A.A., van Roermund P.M., Lammens J., van Melkebeek J., Verbout A.J., Lafeber E.P. Can Ilizarov joint distraction delay the need for arthrodesis of the ankle? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(5):720–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volpon J.B., Lima R.S., Shimano A.C. Tratamento da forma ativa da doença de Legg-Calvé-Perthes pela artodiástase. Rev Bras Ortop. 1998;33(1):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kocaoglu M., Kilicoglu O.I., Goksan S.B., Cakmak M. Ilizarov fixator for treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8(4):276–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paley D., Komninakas J. Distraction treatment for Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in the older child. Seventh Annual Scientific Meeting of Association for Study and Application of the Methods of Ilizarov; 12 February, San Francisco; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paley D. Tratamento de necrose da cabeça do femur com artrodiástase do quadril. V Congresso de Ortopedia e Traumatologia do Estado de São Paulo; Santos, São Paulo; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ilizarov G.A. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues. In: Ilizarov G.A., editor. Transosseous osteosynthesis. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1992. pp. 137–255. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kucukkaya M., Kbukcuoglu Y., Ozturk I., Kuzgun U. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in childhood: the results of treatment with articulated distraction method. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(6):722–728. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]