Abstract

Key points

Mice with Ca2+–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) constitutive pseudo‐phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor RyR2 at Ser2814 (S2814D+/+ mice) exhibit a higher open probability of RyR2, higher sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ leak in diastole and increased propensity to arrhythmias under stress conditions.

We generated phospholamban (PLN)‐deficient S2814D+/+ knock‐in mice by crossing two colonies, S2814D+/+ and PLNKO mice, to test the hypothesis that PLN ablation can prevent the propensity to arrhythmias of S2814D+/+ mice.

PLN ablation partially rescues the altered intracellular Ca2+ dynamics of S2814D+/+ hearts and myocytes, but enhances SR Ca2+ sparks and leak on confocal microscopy.

PLN ablation diminishes ventricular arrhythmias promoted by CaMKII phosphorylation of S2814 on RyR2.

PLN ablation aborts the arrhythmogenic SR Ca2+ waves of S2814D+/+ and transforms them into non‐propagating events.

A mathematical human myocyte model replicates these results and predicts the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake required to prevent the arrhythmias induced by a CaMKII‐dependent leaky RyR2.

Abstract

Mice with constitutive pseudo‐phosphorylation at Ser2814‐RyR2 (S2814D+/+) have increased propensity to arrhythmias under β‐adrenergic stress conditions. Although abnormal Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) has been linked to arrhythmogenesis, the role played by SR Ca2+ uptake remains controversial. We tested the hypothesis that an increase in SR Ca2+ uptake is able to rescue the increased arrhythmia propensity of S2814D+/+ mice. We generated phospholamban (PLN)‐deficient/S2814D+/+ knock‐in mice by crossing two colonies, S2814D+/+ and PLNKO mice (SD+/+/KO). SD+/+/KO myocytes exhibited both increased SR Ca2+ uptake seen in PLN knock‐out (PLNKO) myocytes and diminished SR Ca2+ load (relative to PLNKO), a characteristic of S2814D+/+ myocytes. Ventricular arrhythmias evoked by catecholaminergic challenge (caffeine/adrenaline) in S2814D+/+ mice in vivo or programmed electric stimulation and high extracellular Ca2+ in S2814D+/− hearts ex vivo were significantly diminished by PLN ablation. At the myocyte level, PLN ablation converted the arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves evoked by high extracellular Ca2+ provocation in S2814D+/+ mice into non‐propagated Ca2+ mini‐waves on confocal microscopy. Myocyte Ca2+ waves, typical of S2814D+/+ mice, could be evoked in SD+/+/KO cells by partially inhibiting SERCA2a. A mathematical human myocyte model replicated these results and allowed for predicting the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake required to prevent the arrhythmias induced by a Ca2+–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase (CaMKII)‐dependent leaky RyR2. Our results demonstrate that increasing SR Ca2+ uptake by PLN ablation can prevent the arrhythmic events triggered by SR Ca2+ leak due to CaMKII‐dependent phosphorylation of the RyR2‐S2814 site and underscore the benefits of increasing SERCA2a activity on SR Ca2+‐triggered arrhythmias.

Key points

Mice with Ca2+–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) constitutive pseudo‐phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor RyR2 at Ser2814 (S2814D+/+ mice) exhibit a higher open probability of RyR2, higher sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ leak in diastole and increased propensity to arrhythmias under stress conditions.

We generated phospholamban (PLN)‐deficient S2814D+/+ knock‐in mice by crossing two colonies, S2814D+/+ and PLNKO mice, to test the hypothesis that PLN ablation can prevent the propensity to arrhythmias of S2814D+/+ mice.

PLN ablation partially rescues the altered intracellular Ca2+ dynamics of S2814D+/+ hearts and myocytes, but enhances SR Ca2+ sparks and leak on confocal microscopy.

PLN ablation diminishes ventricular arrhythmias promoted by CaMKII phosphorylation of S2814 on RyR2.

PLN ablation aborts the arrhythmogenic SR Ca2+ waves of S2814D+/+ and transforms them into non‐propagating events.

A mathematical human myocyte model replicates these results and predicts the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake required to prevent the arrhythmias induced by a CaMKII‐dependent leaky RyR2.

Abbreviations

- Adr

adrenaline

- AE

anion exchanger

- AP

action potential

- APD50

AP duration at 50% repolarization

- Caff

caffeine

- CaMKII

Ca2+–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase

- CICR

Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release

- CPA

cyclopiazonic acid

- CRU

Ca2+ release unit

- CYTO

cytoplasm

- DAD

delayed afterdepolarization

- DC

dyadic cleft

- EAD

early afterdepolarization

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- HF

heart failure

- HR

heart rate

- Ileak

SR diastolic Ca2+ flux

- INa

Na+ current

- ICaL

Ca2+ current through L‐type Ca2+ channels

- INCXdir

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger direct mode current

- INCXrev

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reverse mode current

- Iup

SR Ca2+ uptake flux

- Irel

SR Ca2+ release flux

- Iti

transient inward current

- LCC

L‐type Ca2+ channel

- LVFS

left ventricular fractional shortening

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- PLN

phospholamban

- PLNKO

PLN knock‐out

- RyR2

cardiac ryanodine receptor

- SAP

spontaneous action potential

- S2814D+/+

knock‐in mice with constitutive pseudo‐phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814

- S2814D+/−

heterozygous S2814D mice

- SD+/+/KO

mice resultant from crossbreeding PLNKO and RyR2‐S2814D mice

- SD+/−/KO

mice resultant from crossbreeding PLNKO and RyR2‐S2814D+/− mice

- SD+/+/KOsim and S2814D+/+sim

simulated conditions of SD+/+/KO and S2814D+/+ mice

- SERCA2a

SR Ca2+‐ATPase

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TP

ten Tusscher–Panfilov

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

- WT

wild‐type

- xfer

conductance parameter from dyadic cleft to cytosol

Introduction

Mechanical dysfunction and arrhythmias are hallmark features of heart failure (HF), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Cleland et al. 2002; Mozaffarian et al. 2007), and it is now well established that aberrant Ca2+ handling is a main cause of these two characteristic HF disarrays (Hasenfuss & Pieske, 2002; Pogwizd & Bers, 2004; Luo & Anderson, 2013). Indeed, a large fraction of ventricular arrhythmias in HF are thought to be initiated at the cellular level by focal triggered mechanisms such as abnormal spontaneous Ca2+ discharges from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which propagate as regenerative Ca2+ waves through cardiac cells (Laurita & Rosenbaum, 2008). Spontaneous Ca2+ waves are arrhythmogenic as a consequence of activating inward membrane currents, mainly the electrogenic Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) working in the forward mode (Pogwizd & Bers, 2004; Laurita & Rosenbaum, 2008; Luo & Anderson, 2013).

An enhanced SR Ca2+ leak occurs under conditions in which SR Ca2+ load exceeds a threshold that is largely determined by the particular state of the ryanodine receptor RyR2. For instance, RyR2 point mutations render the channel more prone to spontaneous SR Ca2+ release during adrenergic stimulation. Patients with this inherited anomaly exhibit catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, a known cause of sudden cardiac death (Liu & Priori, 2008). Phosphorylation of RyR2 by Ca2+–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) at the S2814 site has also been associated with an increase in SR Ca2+ leak and arrhythmogenesis in cardiac pathologies of different aetiology (Ai et al. 2005; Said et al. 2008, 2011; Chelu et al. 2009; Gonano et al. 2011). CaMKII is up‐regulated and more active in HF and different type of experimental evidence indicate that RyR2‐S2814 phosphorylation is a main underlying mechanism of arrhythmias in this disease (Ai et al. 2005). These results suggested a crucial role of RyR2 altered activity on triggered arrhythmias. In contrast, the effect of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake on cardiac triggered events is not clear and there is concern about whether the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake, which has been shown to be a useful therapy to revert the depressed cardiac contractility in human and experimental heart failure (Hajjar et al. 2008), is protective against Ca2+ triggered arrhythmias or exacerbates them.

This concern has experimental support since contradictory results have been obtained by either decreasing or increasing SR Ca2+ uptake (Lukyanenko et al. 1999; Davia et al. 2001; del Monte et al. 2004; Landgraf et al. 2004; Prunier et al. 2008; Stokke et al. 2010; Bai et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015). The clue to explaining these inconsistent findings may rest, at least in part, in the opposite effects inherent to the augmented SR Ca2+ uptake itself on cytosolic Ca2+, i.e. increasing the rate of SR Ca2+ uptake would reduce cytosolic Ca2+ overload and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias, but would necessarily increase SR Ca2+ content, favouring RyR2 Ca2+ sensitization, improving diastolic SR Ca2+ leak and the risk of Ca2+ waves. This situation might be exacerbated if the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake coexists with an increase in the open probability of RyR2, as that produced by CaMKII‐dependent phosphorylation of the S2814 site (Ai et al. 2005), and may contribute to favouring a futile cycle of increased SR Ca2+ uptake and leak with an additional metabolic cost, due to SERCA2a ATP consumption. Thus, the beneficial effects of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake may turn out to be deleterious under conditions in which the balance between SR Ca2+ uptake and leak is lost.

Previous studies demonstrated that ventricular myocytes from S2814D+/+ mice, in which the Ser2814 CaMKII site on RyR2 is constitutively pseudo‐phosphorylated, are prone to arrhythmias (van Oort et al. 2010). In the present work, we crossbred phospholamban knock‐out (PLNKO) mice (PLN−/−) (Luo et al. 1994) with RyR2‐S2814D+/+ knock‐in mice to generate double‐mutant mice, PLN−/−/RyR2‐S2814D+/+ (SD+/+/KO), to test the idea that the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake may rescue S2814D+/+ mice from their typical arrhythmogenic susceptibility. With the aid of a mathematical model we further tested the necessary change in SR Ca2+ uptake required to prevent the arrhythmogenic effect of a CaMKII‐dependent leaky RyR2.

Methods

Ethical approval

All experiments involving mice were performed as per institutional guidelines and appropriate laws, and were approved by the Faculty of Medicine, University of La Plata Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CICUAL no. P03‐01‐15). The authors have read and understood the policies and regulations of The Journal of Physiology as outlined by Drummond (2009) and ensured that all experiments complied with these regulations.

Animals

Experiments were performed in 3‐ to 4‐month‐old male mutant mice with phospholamban ablation (PLNKO mice) (Luo et al. 1994), RyR2‐S2814D+/+ knock‐in mice (van Oort et al. 2010), and mice resulting from crossbreeding PLNKO and RyR2‐S2814D+/+ mice (SD+/+/KO mice). Some experiments in perfused hearts (see Results) were performed in mice resulting from crossbreeding PLNKO and heterozygous RyR2‐S2814D+/− mice. These mice were called SD+/−/KO mice. C57BL/6 mice were used as controls (wild‐type (WT) mice). Mice genotype was confirmed by PCR analysis using mouse tail DNA and specific primers for each mutation.

Histology

A transverse section of the heart was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 h. After paraffin embedding and sectioning, 5 μm sections were stained with Masson's trichrome and picrosirius red techniques. Slides were observed with an Olympus BX53 microscope (Japan) and transmitted to the computer using a digital camera (Olympus DP‐73, Japan). Images were captured using the automatic Multiple Image Alignment process of the cellSens Dimension v1.7 image analysis software (Olympus). The stained areas of collagen were calculated by measuring 10 areas of the septum and ventricular right and left free walls and expressed as percentage of total area measured. Cardiomyocyte transverse diameter was determined in the digital analysis system in cells sectioned at the nuclear level. Sections were treated by means of immunohistochemical technique with a mouse monoclonal antibody against CD34 (endothelial cells; QBend/10, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA). This procedure facilitates myocyte border detection.

Echocardiographic examination

Baseline cardiac geometry and function were evaluated by two‐dimensional M‐mode echocardiography with a 13 MHz linear transducer in conscious mice (3 and 6 months old). The echocardiographic study was performed without anaesthesia, after a procedure habituation period of at least 3 consecutive days. Systolic and diastolic dimensions were assessed according to the American Society of Echocardiography's guidelines (Lang et al. 2005). Global LV systolic function was determined by calculating left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS):

LVFS = (LVEDD – LVESD / LVEDD) × 100, where LVFS is expressed as a percentage, and LVEDD and LVESD are left ventricular end‐diastolic and end‐systolic diameters, respectively.

Electrocardiogram

Surface electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded in conscious mice, for 30 min, using standard ECG electrodes (lead I) and a PowerLab 4ST data acquisition system (Gonano et al. 2011). Twelve mice (6 SD+/+/KO and 6 WT) were also studied under basal conditions with ECG telemetry (Contreras et al. 2014).

Surface ECG was recorded for 10 min and then a catecholaminergic challenge (caffeine and adrenaline, 120 mg kg−1 and 1.6 mg kg−1, respectively) was applied to unmask the presence of arrhythmias under ‘stress’ conditions.

Ex vivo experiments: intact hearts. Intracellular Ca2+ and action potentials

Animals were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ketamine–diazepam (100 mg kg−1 and 5 mg kg−1, respectively). Central thoracotomy and heart excision were performed immediately after phase III anaesthesia was reached, verified by the loss of pedal withdrawal reflex. Isolated hearts were perfused according to the Langendorff technique at constant temperature (37°C) and flow (2–3 ml min−1) as previously described (Vittone et al. 2002; Said et al. 2008).

Rhod‐2, Mag‐Fluo‐4 and Di‐8‐ANEPPS (Invitrogen) were used to evaluate intracellular Ca2+ transients in the cytosol and the SR and transmembrane action potentials (APs), respectively, at the epicardial layer of intact mouse hearts, as previously described (Valverde et al. 2010; Ferreiro et al. 2012), using a custom‐made setup for pulse local‐field fluorescence (PLFF) microscopy (Mejia‐Alvarez et al. 2003). After mounting and loading, hearts were paced at 5 Hz for approximately 15 min and intracellular Ca2+ or transmembrane potentials were recorded according to the different protocols (see Results). The recordings were obtained by gently placing one end of the optic fibre on the tissue.

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements in intact isolated myocytes

Myocytes were isolated by enzymatic digestion as previously described (Palomeque et al. 2009). Isolated myocytes were loaded with Fura‐2/AM. Ca2+ fluorescence was measured in an Myocyte Calcium and Contractility System (IonOptix, Milton, MA, USA) (Palomeque et al. 2009).

Confocal imaging of intact cardiac myocytes

Freshly isolated mouse ventricular myocytes were loaded with 10 μm fluo‐3‐AM (Molecular Probes) in Tyrode buffer containing 2.5 mm Ca2+ for 20 min at room temperature, and mounted in a small chamber placed onto an inverted microscope equipped with a 63× objective as previously described (Palomeque et al. 2009). After stabilization (usually 3–5 min), confocal line‐scanning (512 × 512 pixels and 4.3 ms per line) was performed along the longitudinal axis of cells (avoiding nuclei), using the Zeiss LSM 210 confocal system in quiescent cells. The fluo‐3‐AM loaded myocytes were excited using the 488 nm argon laser and the fluorescence emission was recorded at 500–550 nm. This procedure was repeated under ‘stress’ conditions, i.e. in the presence of 6.0 mm Ca2+. Extracellular Ca2+ was increased stepwise (2.5, 4.0 and 6.0 mm) to avoid cell damage.

Image processing

Ca2+ sparks were measured using the ‘Sparkmaster’ plugin for ImageJ (Picht et al. 2007). Ca2+ waves and mini‐waves were visually counted and classified, by two different operators, according to the following definitions. A propagated Ca2+ wave was defined as a continuous wave front in the line scan image visualized as a robust fluorescent line that propagates across the full width of the myocyte without breaking. A mini‐wave was defined as a fluorescent line that breaks without propagating across the full width of the cell. Image processing software was developed using Python language. This program allowed us to recheck the results obtained by eye. The main library used for this task was scikit‐image (http://scikit‐image.org/) (van der Walt et al. 2014), which is a freely available open source collection of algorithms that allows image manipulation. The program was also used to estimate SR Ca2+ leak by multiplying Ca2+ spark frequency (number of events per second, normalized to 100 μm) by the total fluorescence of each spark (sum of fluorescence of each pixel).

Ca2+ wave velocity was calculated on a linear region of the record, dividing a given distance covered by the wave by the corresponding time, as previously described (Mattiazzi et al. 2015). The different individual Ca2+ wave characteristics (amplitude and duration) were analysed by division of the wave into 10 sections, 8 pixels wide. Plots of these sections were averaged to calculate peak fluorescence and rate constants of the decay phase of a wave.

Modelling

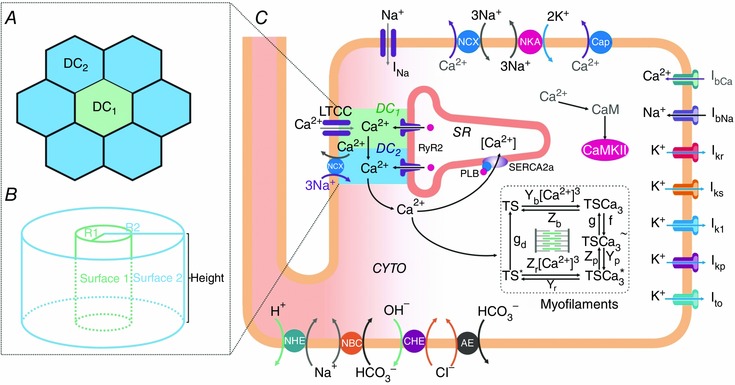

A modified ten Tusscher–Panfilov (TP) human ventricular myocyte model (ten Tusscher & Panfilov, 2006) was used, incorporating acid–base regulation, a reformed RyR2 receptor and CaMKII effects on flows based on experimental data (Lascano et al. 2013), and a recently reformulated contractile part (Negroni et al. 2015). In addition, as a global representation of Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release (CICR) mechanism, two dyadic clefts (DCs) were considered, the first (DC1) consisting of the Ca2+ release units (CRUs) (RyR2 forming part of the RyR2 cluster) facing the L‐type Ca2+ channel (LCC), and the second (DC2) composed of the remaining CRUs not facing LCC (Inoue & Bridge, 2005). In DC1, [Ca2+] elevation by LCC Ca2+ influx or from an overloaded SR‐induced Ca2+ leak activates CRU opening by CICR. This Ca2+ diffuses to DC2 promoting regenerative CICR release from the neighbouring RyR2. Then, all Ca2+ in DC2 (diffusing from DC1 and/or released from DC2) passes into the bulk cytoplasm (CYTO).

It was assumed that RyR2 activation (either spontaneously or by LCC Ca2+ influx) starts in DC1 and is forced to pass through DC2 before entering CYTO. To represent this concept, the original TP DC volume was postulated as a hexagon surrounded by six other hexagons of the same size. This involved seven CRUs for each LCC, within the range postulated by Izu et al. (2001) and Sato & Bers (2011). Considering that the original TP DC volume was 0.34% of CYTO volume, in this new approach total cleft volume was 2.42% of CYTO volume, similar to the one postulated in the O'Hara human myocyte model (2.94%) (O'Hara et al. 2011). Once the volumes were defined, the DC compartments were simplified as two concentric cylinders (see Fig. 9 B in Results for further details), allowing Ca2+ diffusion through their lateral surfaces (surface 1 and surface 2). To represent this concept, the conductance parameter from the single DC to CYTO (xfer) in the TP model gave rise to xfer1 and xfer2 parameters, imposing a total conductance equivalent to xfer1 and xfer2 arranged in series.

| (1) |

Figure 9. Schematic diagram of the model .

Human myocyte model (C) including ion pumps and exchangers responsible for action potential, Ca2+ management, force development, pHi and Ca2+–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) regulation. Our previous model (Lascano et al. 2013) was modified by the addition of a second dyadic cleft: DC1 and DC2. The model is coupled to the myofilament force development model consisting of 5‐state troponin systems (TS) with Ca2+ binding at the myofilament level (Negroni et al. 2015). CYTO, cytosol; LTCC, L‐type Ca2+ channels; NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; NKA, Na+/K+‐ATPase; Cap, membrane Ca2+‐ATPase; NHE, Na+/H+ exchanger; NBC, Na+–HCO3 − cotransporter; CHE, Cl−/OH− exchanger; AE, anion exchanger; I represents different ionic currents (see text for further details). A, detail of the DC structure where DC1 is surrounded by 6 DC2. DC1 represents the dyadic clefts where RyR2 are facing the L‐type Ca2+ channel (LCC) and DC2 the dyadic clefts where RyR2 are not facing LCC. In the original TP model (ten Tusscher & Panfilov, 2006), the single dyadic cleft involves 14.3% of the present total cleft space (DC1+DC2). B, dyadic cleft structure assumed as two concentric cylinders. Surface 1: lateral surface of the cylinder with radius R, representing DC1. Surface 2: lateral surface of the cylinder with radius R2, representing DC2. The planar surfaces limiting the height of the cylinders are the sarcolemmal membrane on one side and the SR membrane on the other (see text for further details).

It was assumed that Ca2+ diffusion was perpendicular to cylinder surface and proportional to xfer; then, surface1 = k × xfer1 and surface2 = k × xfer2. The relationship between the two cylinder lateral surfaces provided the equation to find the numerical xfer1 and xfer2 values.

with K = 6

| (2) |

Solving eqn (1) and eqn (2) systems gives numerical values for xfer1 and xfer2. Lower case k is different from upper case K; the first is the proportionality constant between lateral surface and conductance, and K is the relationship between volume 2 and volume 1.

The DC2 compartment was assumed to have 10% of the TP NCX (Shannon et al. 2004) with the rest in the CYTO membrane. Moreover, Ca2+ flow parameters involving DC1 and DC2 were adjusted to achieve total flows of the original TP model, resulting in adequate stabilized beats (see Results).

The four‐state RyR2 structure regulated by [Ca2+]SR and [Ca2+] in the cleft postulated by Shannon et al. (2004) was used, modified to represent SR Ca2+ leak as Ca2+ flow through the RyR2 modulated by the resting (R) state of this channel (Lascano et al. 2013).

To simulate the behaviour of S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO mice, an increase in RyR2 Ca2+ release and in SERCA2a Ca2+ uptake was added as appropriate. These changes were represented as 50% increased conductance for RyR2 and 50% for SR Ca2+ uptake. These two values were obtained from experimental data, showing an increase in SR Ca2+ leak of 50% in S2814D+/+ mice relative to WT mice (van Oort et al. 2010 and the present results) and an increase in SR Ca2+ uptake of approximately 50% from control values at pCa between 7.0 and 6.5 (Luo et al. 1994). Additionally, increased Ca2+ uptake was accompanied by 25% decrease in RyR2 conductivity to reproduce the reported compensatory mechanism in PLNKO mice (Chu et al. 1998).

To simulate a stress situation similar to the experimental conditions in isolated myocytes and intact hearts, the SR was first loaded with 4.2 mm external [Ca2+]o at 150 stimuli min−1 during 1 min; then the stimulation was stopped and spontaneous action potentials (SAPs) or early or delayed afterdepolarizations (EADs or DADs, respectively) were computed for 12 s. An adrenergic challenge, as the one used in intact mice, was simulated by applying the effect of 100 nm isoproterenol (Iso). Since CaMKII was incorporated into our model and its activity and effects adapt to [Ca2+]i variations (Lascano et al. 2013), only the effects of protein kinase A (PKA) on the different Ca2+ fluxes were simulated based on experimental data, as previously described (Negroni et al. 2015): SERCA2a activity was increased by 40% (equivalent to 68% in SERCA2a K m reduction); I CaL and phospholemman sensitivity were increased by 40% and 20%, respectively. Other PKA targets were modified as previously described (Negroni et al. 2015). Iso effect on SERCA2a activity was not considered in SD+/+/KOsim, due to phospholamban (PLN) ablation. RyR2 conductance was not modified by PKA, considering that most of the evidence indicates that PKA does not appear to significantly influence RyR2 diastolic leakage (Li et al. 2002; Curran et al. 2007). Contraction frequency was modestly increased to 80 beats min−1 after the stabilization period at 70 beats min−1.

Statistics

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± SEM and were evaluated with either unpaired Student's t test or ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, to compare differences between groups. Spontaneous Ca2+ release events were expressed as nonparametric continuous data. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare non‐normal data distribution. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Categorical data were expressed as percentages and compared with Fisher's exact test.

Results

Structural characterization of PLNKO/RyR2‐S2814D+/+ double‐mutant mice (SD+/+/KO)

WT and SD+/+/KO mice were genotyped by PCR analysis using mouse tail DNA and specific primers for WT, PLNKO and S2814D+/+ mutations, as previously described (Luo et al. 1994; van Oort et al. 2010). Cardiac wall dimensions, assessed from haematoxylin–eosin‐stained histological sections of 3‐month‐old mice, were similar between WT and SD+/+/KO hearts: left ventricular anteroposterior diameter 1.33 ± 0.19 vs. 2.01 ± 0.29 mm, left ventricular maximal wall thickness 1.20 ± 0.30 vs. 1.65 ± 0.20 mm, left ventricular minimal wall thickness 0.96 ± 0.09 and 1.05 ± 0.12 mm, septum thickness 1.30 ± 0.14 and 1.23 ± 0.19 μm, respectively (n = 3). Moreover, no significant differences were detected in either myocardial cell transverse diameter (17.40 ± 1.03 μm (WT mice,) vs. 15.50 ± 0.32 μm (SD+/+/KO mice), n = 134 and 139 myocytes, respectively, from 3 hearts, or interstitial fibrosis 4.0 ± 0.5% (WT) vs. 4.5 ± 0.6 % (SD+/+/KO) (n = 3). Table 1 shows that at baseline, cardiac structure and function were similar in young (3‐month‐old) WT and SD+/+/KO mice when determined by echocardiography. Instead, at 6 months, SD+/+/KO exhibited a significant increase in end‐diastolic diameter, systolic ventricular septum wall thickness and left ventricular posterior wall thickness vs. WT mice. An increase in these parameters was also previously observed in S2814D+/+ mice at 12 months (van Oort et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Echocardiographic parameters of WT and SD+/+/KO mice at 3 and 6 months of age

| 3 months old | 6 months old | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | SD+/+KO | WT | SD+/+KO | |

| n | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1) | 651.82 ± 22.80 | 707.11 ± 17.03 | 618.82 ± 25.8 | 623.68 ± 7.89 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 92.86 ± 0.38 | 94.54 ± 2.43 | 91.92 ± 1.00 | 94.70 ± 0.30 |

| LVFS (%) | 31.08 ± 0.49 | 34.51 ± 3.67 | 30.66 ± 1.01 | 34.19 ± 1.49 |

| ESD (mm) | 1.02 ± 0.03 | 0.95 ± 0.06 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 1.00 ± 0.03 |

| EDD (mm) | 2.83 ± 0.07 | 3.02 ± 0.15 | 2.72 ± 0.09 | 3.13 ± 0.11*‡ |

| IVSs (mm) | 1.39 ± 0.04 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 1.26 ± 0.09† | 1.60 ± 0.07*‡ |

| IVSd (mm) | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.68 ± 0.02* | 0.70 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.03 |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.61 ± 0.08 | 1.59 ± 0.12 | 1.26 ± 0.09† | 1.60 ± 0.07*‡ |

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.02* | 0.68 ± 0.03† | 0.85 ± 0.04* |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening; ESD and EDD, end‐systolic and end‐diastolic diameter; IVSs and IVSd, intraventricular septum wall thickness in systole or diastole; LVPWs and LVPWd, LV posterior wall thickness in systole or diastole. *P < 0.05 WT vs. SD+/+/KO; † P < 0.05, 3 months vs. 6 months for WT; ‡ P < 0.05, 3 months vs. 6 months for SD+/+/KO.

Effects of PLN ablation on altered Ca2+ dynamics of S2814D+/+ mice

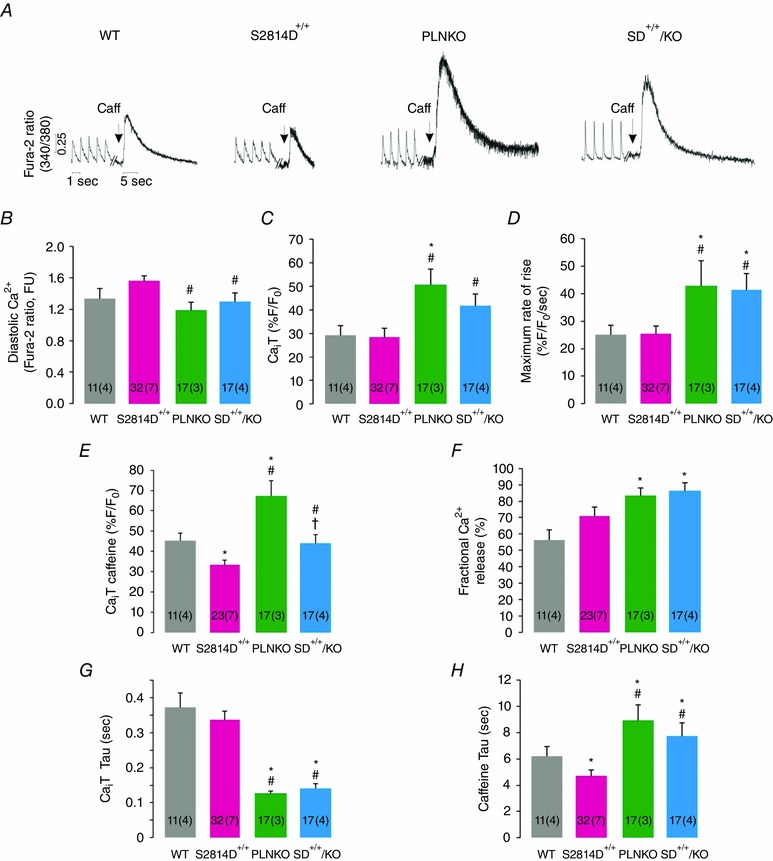

Figure 1 shows typical recordings (Fig. 1 A) and overall results (Fig. 1 B–H) of intracellular Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ dynamics in cardiac myocytes of SD+/+/KO and S2814D+/+ mice. Records and results of PLNKO and WT myocytes are also displayed for comparison. In SD+/+/KO mice, diastolic Ca2+ was significantly decreased and twitch Ca2+ transient amplitude significantly enhanced with respect to S2814D+/+ myocytes (Fig. 1 B and C), whereas the rate of rise of Ca2+ transient was higher than in S2814D+/+ and WT myocytes (Fig. 1 D). SR Ca2+ load estimated by the caffeine‐induced Ca2+ transient amplitude – which was diminished in S2814D+/+ with respect to WT myocytes, as expected from a leaky RyR2 – was significantly enhanced by PLN ablation in SD+/+/KO myocytes (Fig. 1 E), whereas fractional Ca2+ release was more improved in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ myocytes (Fig. 1 F). Moreover, SD+/+/KO myocytes exhibited a faster time constant of twitch Ca2+ transient decay and a slower time constant of caffeine‐induced Ca2+ transient decay than S2814D+/+ (Fig. 1 G and H).

Figure 1. PLN ablation enhances Ca2+ dynamics of S2814D+/+ myocytes .

Basal intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in electrically stimulated (1.0 Hz) cardiac myocytes of WT, S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO mice. A, typical examples of twitch‐ and caffeine‐induced Ca2+ transients. B, diastolic Ca2+. C, twitch Ca2+ transient (CaiT) amplitude. D, maximal rate of rise of CaiT. E, caffeine‐induced CaiT amplitude. F, fractional Ca2+ release. G and H, twitch‐ and caffeine‐induced CaiT decay (tau). Caffeine‐induced CaiT decay, used to estimate NCX activity, was higher in PLNKO mice vs. WT. A similar increase was observed in SD+/+/KO mice. In this and the following figures, the number of myocytes and animals (between parenthesis), are shown inside the bars. FU, fluorescence units. *P < 0.05 vs. WT; # P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+.

Analogous changes in Ca2+ dynamics were observed in SD+/+/KO mice when cytosolic and intra‐SR Ca2+ were measured at the epicardial layer of the intact beating heart (Fig. 2). Cytosolic and intra‐SR Ca2+ transients relaxed faster and restitution of Ca2+ transients was more rapid in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ and WT mice and similar to PLNKO mice, which is consistent with a decrease in RyR2 refractoriness produced by the enhanced SR Ca2+ uptake due to PLN ablation in PLNKO and SD+/+/KO myocytes (Huser et al. 1998; Szentesi et al. 2004). Instead, no differences in action potential restitution curves were observed between SD+/+/KO and S2814D+/+ animals.

Figure 2. PLN ablation increased the cytosolic and SR Ca2+ relaxation and Ca2+ transient restitution of S2814D+/+ intact hearts .

Basal intracellular Ca2+ dynamics at the epicardial layer of the intact beating heart of WT, S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO mice. A and B, upper panel, typical examples of cytosolic Ca2+ transient (Rhod‐2 fluorescence) (A) and intra‐SR Ca2+ transient records (Mag‐fluo‐4 fluorescence) (B). Lower panel, overall results showing the time constant (tau) of cytosolic (A) and intra‐SR Ca2+ decay (B) in the four groups of hearts. Cytosolic and intra‐SR Ca2+ both decayed faster in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ and WT mice and similar to PLNKO hearts. C and D, restitution curves for cytosolic Ca2+ transient and action potential (above) and their respective exponential time constants (below). Whereas Ca2+ restitution curves increased faster in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ mice, action potential restitution curves were similar in both groups. The inset of the figure depicts the experimental protocol. *P < 0.05 vs. WT; # P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+ and & P < 0.05 vs. PLNKO.

Taken together the results indicate that SD+/+/KO mice combine, at the functional cellular level, the enhanced SR Ca2+ uptake produced by PLN ablation and the decrease in SR Ca2+ load (relative to PLNKO) produced by the enhanced SR Ca2+ leak typical of S2814D+/+ mice.

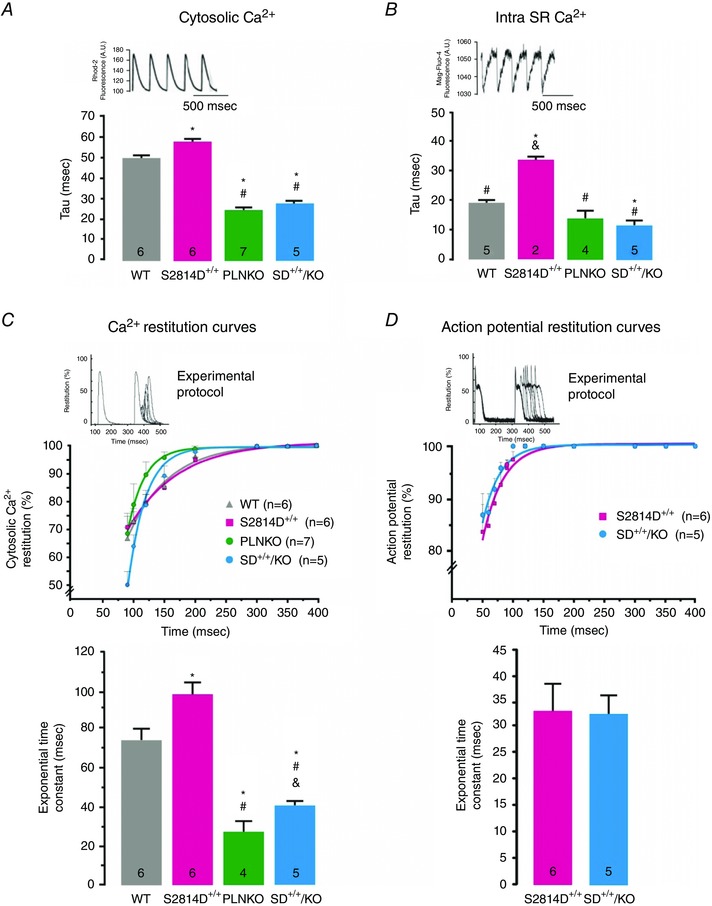

PLN ablation diminished ventricular arrhythmias promoted by CaMKII phosphorylation of S2814 on RyR2

To evaluate the effects of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake on the arrhythmogenic propensity typical of CaMKII‐mediated RyR2 phosphorylation, we used 3‐ to 4‐month‐old S2814D+/+ knock‐in and SD+/+/KO mice to study ECG waveforms. S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO mice had normal heart rhythm at rest, with most of the electrophysiological parameters such as PQ and QRS being unaltered, although there was a modest but significantly prolonged QT interval, a finding also observed in PLNKO (Table 2). However, when challenged with an i.p. injection of caffeine/adrenaline, the ECG response was completely different between S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO mice. Whereas S2814D+/+ mice exhibited a high incidence of premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), in agreement with previous findings (van Oort et al. 2010), PVCs were significantly less frequent in SD+/+/KO mice (Fig. 3 A–C). Moreover the high incidence of sustained bidirectional ventricular tachycardia seen in S2814D+/+ mice (4 out of 5), was completely offset in SD+/+/KO animals (0 out of 6, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3 D).

Table 2.

ECG basal parameters in conscious mice

| ECG parameter | WT | S2814D+/+ | PLNKO | SD+/+/KO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (beats min−1) | 598.0 ± 52.2 | 663.9 ± 14.7 | 543.5 ± 36.0† | 649.9 ± 16.2 |

| RR (ms) | 111.4 ± 7.2 | 90.9 ± 2.6* | 107.8 ± 10.1 | 90.4 ± 2.0* |

| PR (ms) | 35.8 ± 1.2 | 35.4 ± 1.0 | 36.5 ± 1.2 | 32.9 ± 0.8 |

| P (ms) | 14.1 ± 2.0 | 11.2 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 0.5 |

| QRS (ms) | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 13.8 ± 0.7 | 11.5 ± 0.8 |

| QT (ms) | 47.1 ± 1.1 | 45.9 ± 1.3 | 70.0 ± 8.6*,† | 53.1 ± 2.4‡ |

| QTc (ms) | 44.9 ± 1.8 | 48.1 ± 1.3 | 67.0 ± 4.9*,† | 55.7 ± 2.1‡ |

HR, heart rate; RR, RR period duration; PR, PR interval duration; P, P wave duration; QRS, QRS complex duration; QT, QT interval duration; QTc, corrected QT. Of note, SD+/+/KO mice showed a prolongation of the QT interval, similar to that observed in PLNKO mice. Although we did not explore the cause of this prolongation, it may result from the down‐regulation of outward K+ currents that has been described in the presence of similar chronic alteration of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, in mice overexpressing SERCA2a (Xu et al. 2005). *P < 0.05 vs. WT, † P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+, ‡ P < 0.05 vs. PLNKO (n = 4–11 for the different groups).

Figure 3. PLN ablation rescues the propensity to ventricular arrhythmias promoted by CaMKII constitutive CaMKII RyR2 phosphorylation of RyR2 at the S2814 site in vivo .

A and B, representative ECG tracings in conscious S2814D+/+ knock‐in mice and SD+/+/KO mice respectively, at rest and after i.p. injection of caffeine/adrenaline (Caff/Adr). Arrows in S2814D+/+ tracings indicate premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (BVT) was observed in the majority of S2814D+/+ mice after Caff/Adr challenge. PVCs were rare and BVT was completely absent in SD+/+/KO mice. C and D, box plot showing the frequency of PVCs and incidence of VT, respectively, in S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO mice after Caff/Adr challenge. *P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+.

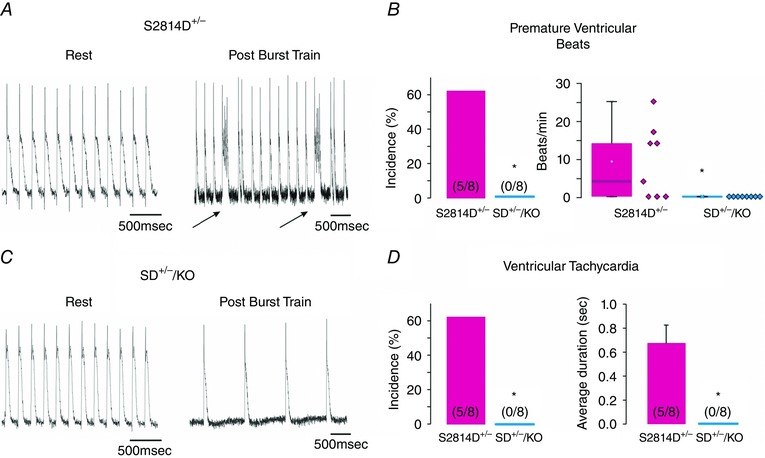

Since homozygous S2814D+/+ mice represent maximal CaMKII‐dependent RyR2 phosphorylation, we further assessed the impact of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake on the propensity of arrhythmias evoked by CaMKII pseudo‐phosphorylation of RyR2 at the S2814 site, in heterozygous S2814D mice (S2814D+/‐ mice) with PLN ablation (S2814D+/− /PLNKO−/−). These mice are referred to as SD+/−/KO mice. These experiments were performed in isolated perfused mouse hearts preloaded with the fluorophore Di‐8‐ANEPPS (Invitrogen) to evaluate transmembrane APs at the epicardial layer of intact mouse hearts (Mejia‐Alvarez et al. 2003). Under basal conditions the APs occurred regularly, following the imposed stimulation frequency. Moreover, AP configuration was similar in both types of mice, although AP duration at 50% repolarization (APD50) tended to be prolonged in SD+/−/KO myocytes relative to S2814D+/−, 41.5 ± 4.7 ms (n = 6) vs. 30.1 ± 4.7 ms (n = 7), respectively, in agreement with the QT prolongation in homozygous SDKO animals shown in Table 2. S2814D+/− and SD+/−/KO hearts were then subjected to three successive 5 s bursts of high frequency pacing (12 Hz) at high extracellular Ca2+ concentration, followed by a pacing period at 1 Hz and high Ca2+, to compare cardiac susceptibility to ventricular ectopic activity of S2814D+/− and SD+/−/KO hearts. Figure 4 shows typical tracings (Fig. 4 A and C) and overall results (Fig. 4 B and D) of these experiments. During the first 3 min after the burst pacing protocol, S2814D+/− hearts did not usually respond to the low pacing frequency imposed and exhibited a spontaneous high frequency (Fig. 4 A) and a significantly higher increase of premature ventricular beats versus SD+/−/KO hearts and in the incidence of trains of ventricular tachycardia (VT) (S2814D+/−, 63% vs. SD+/−/KO, 0%) (Fig. 4 B and D). Taken together, the results indicate that ablation of PLN rescues the in vivo and ex vivo ventricular arrhythmic events promoted by maximal and submaximal CaMKII pseudo‐phosphorylation of RyR2 at the S2814 site.

Figure 4. PLN ablation rescues the propensity to ventricular arrhythmias promoted by constitutive phosphorylation of RyR2 at the S2814 site ex vivo .

A and C , representative action potential tracings at rest and after a high frequency train of stimuli in S2814D+/− (A) and SD+/−/KO mice (C). Arrows in A indicate the occurrence of a spontaneous beat. B, premature ventricular beat incidence (left panel) and frequency (right panel, box plot). D, ventricular tachycardia incidence (left panel) and duration (right panel). *P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/−.

PLN ablation increases Ca2+ spark frequency but decreases the cell‐wide propagating Ca2+ waves produced by constitutive phosphorylation of RyR2 at the S2814 site

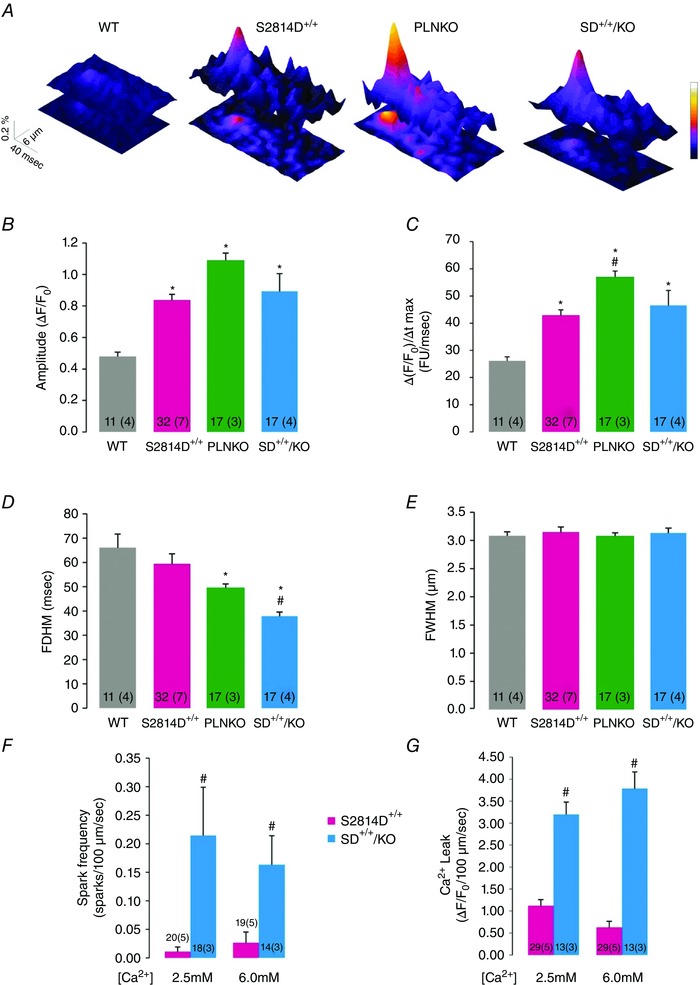

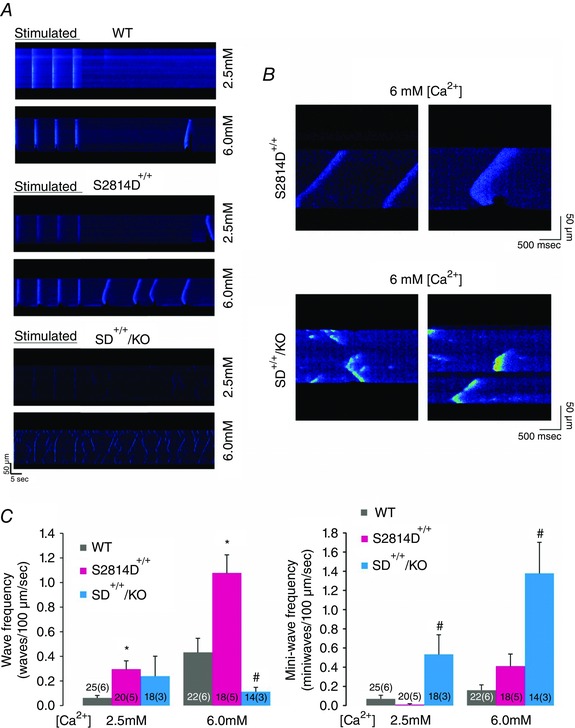

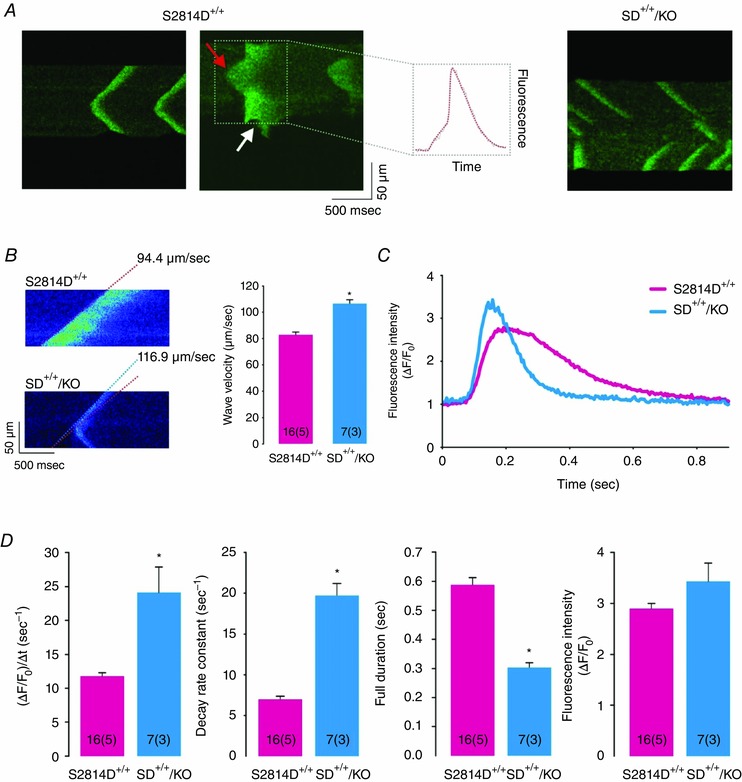

Next, we sought to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the anti‐arrhythmogenic effects of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake by means of PLN ablation. We used confocal microscopy to assess SR Ca2+ sparks and waves in isolated ventricular myocytes. We created conditions for the transition of localized Ca2+ releases into propagating Ca2+ waves by increasing the cellular Ca2+ load via elevation of extracellular [Ca2+]. This procedure is known to increase [Ca2+] in both cytosolic and SR luminal compartments of cardiac myocytes (Wier et al. 1987). Figure 5 A–E displays typical examples and main characteristics of SR Ca2+ sparks at baseline for the four mouse strains (WT, S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO). The amplitude and rate of rise of SR Ca2+ sparks was higher in S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO with respect to WT myocytes, whereas full duration at half‐maximum was significantly reduced in PLNKO and SD+/+/KO vs. S2814D+/+ and WT myocytes. Figure 5 F and G shows that when S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes were submitted to 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+, the frequency of Ca2+ sparks and the calculated SR Ca2+ leak was higher in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ myocytes, consistent with the overall higher SR Ca2+ load in SD+/+/KO cells (see Fig. 1). We then examined the occurrence and characteristics of Ca2+ waves in S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes. Figure 6 A, upper and middle panels, shows typical images of cell‐wide propagating Ca2+ waves displayed by WT and S2814D+/+ myocytes when exposed to high extracellular Ca2+. In contrast, in SD+/+/KO myocytes, Ca2+ waves were mostly replaced by non‐propagating Ca2+ events, known as mini‐waves (Fig. 6 A lower panel). Figure 6 B shows expanded line scan images at high extracellular Ca2+ to further illustrate the predominance of Ca2+ waves in S2814D+/+ myocytes and of Ca2+ mini‐waves in SD+/+/KO myocytes. The overall results of these experiments are depicted in Fig. 6 C. At 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+, S2814D+/+ myocytes showed a significantly higher frequency of Ca2+ waves compared to WT and SD+/+/KO myocytes. Thus, in spite of the higher SR Ca2+ leak observed in SD+/+/KO myocytes vs. S2814D+/+ (Fig. 5), fully propagating events paradoxically predominated in S2814D+/+, whereas in SD+/+/KO myocytes there was a significantly higher proportion of mini‐waves over waves. Figure 7 shows main characteristics of Ca2+ waves in S2814D and SD+/+/KO mice at 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+. Figure 7 A illustrates an example of a Ca2+ wave (red arrow) in a S2814D+/+ myocyte, associated with a triggered Ca2+ transient and cell contraction (white arrow). This is a common finding in S2814D+/+ but not in SD+/+/KO myocytes, which strongly supports the notion that a Ca2+ wave is an arrhythmogenic event, triggering an action potential and the associated contraction. Figure 7 B and C shows Ca2+ wave propagation and typical time courses of wave fluorescence signals from S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocyte line scans. As indicated, Ca2+ waves propagated faster in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ mice. Figure 7 D shows the overall results of Ca2+ wave properties: whereas fluorescence intensity rose and decayed faster in SD+/+/KO vs. S2814D+/+ myocytes, full duration of fluorescence was shorter and the resultant peak fluorescence intensity showed a trend to be higher in SD+/+/KO myocytes vs. S2814D+/+, without reaching statistically significant levels.

Figure 5. Typical space–time plot (A) and main characteristics (B–E) of spontaneous SR Ca2+ sparks under basal conditions in the different groups of myocytes .

Spark amplitude (B) and the rate of rise of Ca2+ sparks (C) are higher in S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO myocytes. Full duration at half‐maximum (FDHM, D) was decreased in PLNKO and SD+/+/KO vs. S2814D+/+ and WT and full width at half‐maximum (FWHM, E), was similar in all groups. F and G, overall results showing the frequency of Ca2+ sparks and the estimated SR Ca2+ leak, respectively, in S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes. FU, fluorescence units. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, # P < 0.05 vs. S2814D.

Figure 6. PLN ablation rescues the propensity to SR Ca2+ propagating events of S2814D+/+ myocytes .

A, typical confocal linescan images obtained in isolated myocytes from WT, S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes at 2.5 and 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+. Myocytes were stimulated at constant frequency (0.5 Hz). When stimulation was stopped, Ca2+ waves appeared in S2814D+/+ mice. In contrast, Ca2+ mini‐waves were present at 2.5 mm Ca2+ and further increased at 6.0 mm Ca2+ in SD+/+KO myocytes. In this example mini‐waves occurred simultaneously at multiple sites but they were soon interrupted. B, amplified confocal linescan images obtained at 6.0 mm Ca2+, showing Ca2+ waves (upper panel) and Ca2+ mini‐waves (lower panel) typically displayed by S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes, respectively. C, overall results of Ca2+ wave frequency (right panel) and Ca2+ mini‐wave frequency (left panel) at low and high extracellular Ca2+. Ca2+ waves frequency was significantly higher in isolated S2814D+/+ myocytes vs. WT myocytes at 2.5 and 6.0 mm Ca2+. Ablation of PLN did not modify Ca2+ wave frequency in SD+/+/KO myocytes at 2.5 mm Ca2+ but significantly decreased it at 6.0 mm Ca2+. Moreover, PLN ablation increased Ca2+ mini‐wave frequency at 2.5 and 6 mm Ca2+. *P < 0.05 vs. WT; # P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+.

Figure 7. Main characteristics of Ca2+ waves in S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes .

A, typical confocal linescan images of isolated S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO myocytes at 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+, to illustrate the association of a wave (red arrow) with a triggered Ca2+ transient and myocyte contraction (see indentation in fluorescence signal, white arrow). B, confocal linescan examples and average results of the velocity of propagation of Ca2+ waves at 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+. Ca2+ waves are faster in SD+/+/KO than in S2814D+/+ myocytes. Broken lines indicate that the slope of front wave propagation was higher in SD+/+/KO vs. S2814D+/+ myocytes. C, Ca2+ wave profiles from a S2814D+/+ and a SD+/+/KO myocyte. D, analysis of Ca2+ wave profiles indicates that SD+/+/KO Ca2+ waves rose and decayed faster and were shorter in duration than S2814D+/+ Ca2+ waves, but they were similar in magnitude. *P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+.

Taken together these results indicate that ablation of PLN was able to reverse the propensity of S2814D+/+ myocytes to trigger arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves under stress conditions by converting most of the propagating Ca2+ waves into non‐propagation Ca2+ events. The reduced duration of the remaining Ca2+ waves in SD+/+/KO myocytes would also contribute to reduce the incidence of arrhythmias in these myocytes, by decreasing the time period of Ca2+ efflux from the cell (O'Neill et al. 2004).

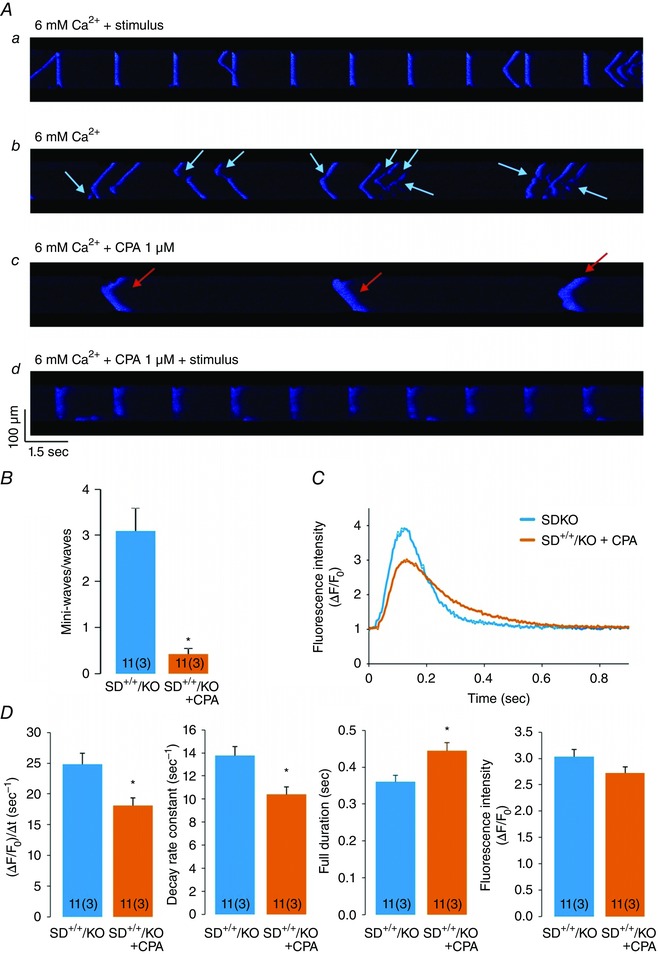

Inhibition of SERCA2a sets back the protective effects of PLN ablation in SD+/+/KO myocytes

As a proof of concept of the beneficial effects of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake on Ca2+ triggered SR Ca2+ waves due to CaMKII constitutive pseudo‐phosphorylation of RyR2 at the S2814 site, we performed experiments in SD+/+/KO isolated myocytes treated with 1 μm of the SERCA2a inhibitor cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and submitted to the same stress protocol described above. It has been previously shown that this CPA concentration inhibits SERCA2a activity by approximately 80% (Schwinger et al. 1997). In our conditions, 1 μm CPA decreased the time constant of Ca2+ transient decline by 79.6 ± 28.0 % (P< 0.05, n=6). Figure 8 A describes a typical experiment in an isolated SD+/+/KO myocyte. Figure 8 Aa depicts paced Ca2+ transients at 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+ concentration. Figure 8 Ab shows the typical mini‐waves displayed by these myocytes when stimulation was stopped. After addition of 1 μm CPA, Ca2+ mini‐waves shifted to fully propagating Ca2+ waves (Fig. 8 Ac). Paced transients of SD+/+/KO in the presence of CPA (Fig. 8 Ad) show that transients are prolonged when compared to the absence of CPA (first panel), mimicking the behaviour of S2814D+/+ myocytes. Figure 8 B shows the overall results of these experiments: after CPA treatment, the relationship Ca2+ mini‐waves/waves observed in SD+/+/KO myocytes was significantly decreased. The main characteristics of Ca2+ waves in SD+/+/KO myocytes at 6.0 mm extracellular Ca2+ before and after treatment with CPA are shown in Fig. 8 C and D. After treatment with CPA, the characteristic SD+/+/KO Ca2+ waves shifted to those of S2814D+/+ Ca2+ waves, i.e. they were significantly slower and longer in duration than but similar in amplitude to SD+/+/KO waves before CPA treatment. These findings confirm the protective effect of PLN ablation on arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves induced by constitutive phosphorylation of RyR2‐S2814.

Figure 8. Results of the effects of SERCA2a inhibition on the ratio Ca2+ mini‐waves/Ca2+ waves and the characteristics of Ca2+ waves in SD+/+/KO myocytes .

A, confocal images showing the sequential behaviour of a SD+/+/KO myocyte after treatment with 1 μm of the SERCA2a inhibitor cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) at high extracellular Ca2+. Aa, confocal images of Ca2+ transients in a SD+/+/KO myocyte when paced at constant frequency. Ab, high Ca2+‐induced SR Ca2+ mini‐waves (light blue arrows) after stimulation was stopped. Ac, high Ca2+‐induced SR Ca2+ waves (red arrows) in the presence of CPA. Ad, SD+/+/KO myocyte in the presence of CPA, paced at constant frequency. Addition of CPA transforms Ca2+ mini‐waves, typical of SD+/+/KO at high Ca2+, into Ca2+ waves, typical of S2814D+/+ myocytes. B, inhibition of SERCA2a with 1 μm of CPA decreases Ca2+ mini‐waves and increases Ca2+ waves, so that the ratio Ca2+ mini‐waves/Ca2+ waves significantly decreases. C, Ca2+ wave profiles in a SD+/+/KO myocyte before and after treatment with CPA. D, analysis of Ca2+ wave profiles. Note that SD+/+/KO Ca2+ waves rose and decayed more slowly and were prolonged after treatment with CPA, similar to S2814D+/+ (see Fig. 7). *P < 0.05 vs. S2814D+/+.

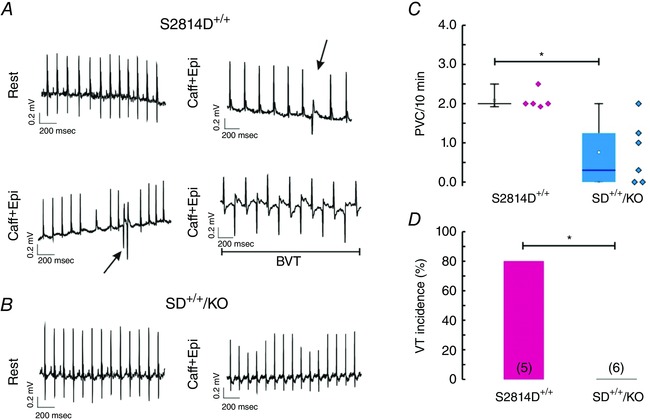

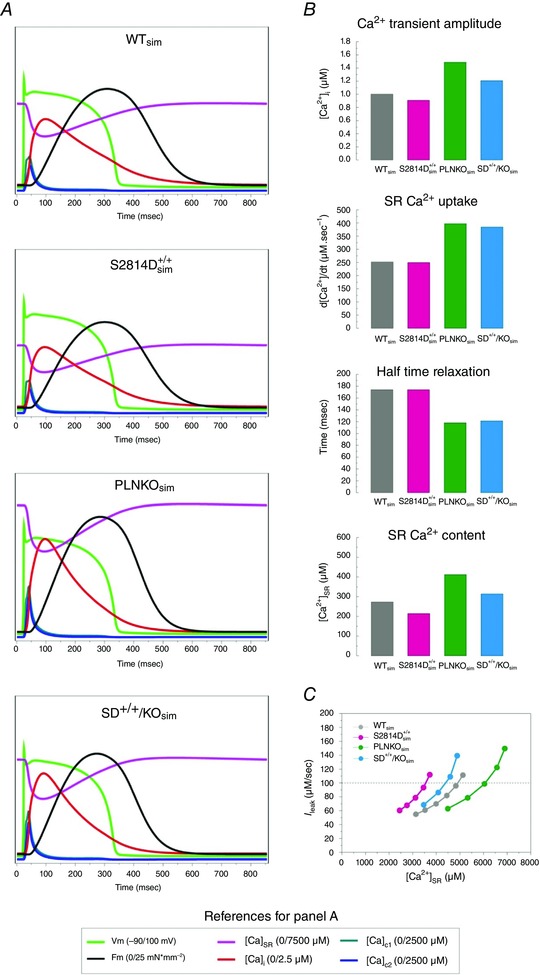

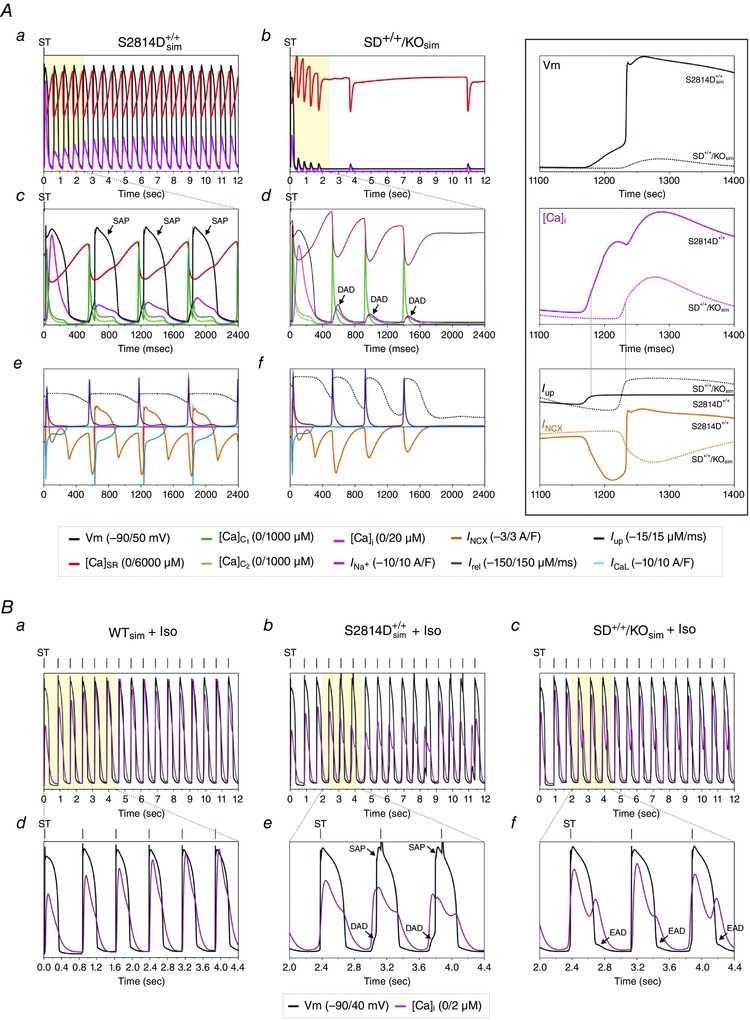

Computational simulation predicts that increasing SR Ca2+ uptake diminishes the spontaneous arrhythmic events in a human myocyte model

The present experiments indicated that increasing SR Ca2+ uptake by PLN ablation was able to rescue the enhanced propensity to arrhythmias of mice with CaMKII‐constitutive phosphorylation of the RyR2‐S2814 site. An intriguing question that arises from these experiments is whether any increase in SR Ca2+ uptake, independently of its extent, is able to counteract the detrimental effect of a CaMKII‐dependent leaky RyR2. To address this question, we utilized an already tested integrated human cardiac myocyte model to gain further insight into the effects of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake on SR‐Ca2+ leak‐triggered arrhythmic events. The model encompasses electrophysiology, Ca2+ dynamics and contractile activity of the human myocyte (Lascano et al. 2013) (see Methods and Fig. 9). Figure 10 A shows typical steady state beats that simulate the distinctive characteristics of WT, S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO cardiac myocytes in human normal conditions (2.0 mm extracellular Ca2+ and 70 stimuli min−1). The main characteristics of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics displayed by the different modelled strains are shown in Fig. 10 B. Under these basal conditions, the myocyte models did not exhibit arrhythmogenic events and reproduced the intracellular Ca2+ transients and SR Ca2+ content pattern observed experimentally in the different mouse groups (compare with experimental results in Fig. 1). As a further model validation, it also exhibited the SR Ca2+ leak–SR Ca2+ content non‐linear relationship reported experimentally (Bers, 2014) (Fig. 10 C). Figure 11 A (left panel) shows the continuous SAPs observed after stimulation was stopped, in conditions that simulate S2814D+/+ myocytes, when challenged with 4.2 mm extracellular Ca2+ and 150 beats min−1. The middle panel of the figure shows that SAPs were not observed when the SD+/+/KO conditions were simulated and only a few DADs appeared after stopping stimulation. To better appreciate the temporal sequence of these distinctive events, the left and middle panels show an expanded view of the different responses corresponding to the last stimulated beat and the following spontaneous events after stopping stimulation. In both S2814D+/+ sim and SD+/+/KOsim stimulated beats, the quasi‐simultaneous upstroke of AP, activation of I Na, I CaL and I NCXrev preceded the increase in Ca2+ in the clefts ([Ca2+]DC1–2) and the Ca2+ transient in cytosol ([Ca2+]i). In the triggering mechanism of SAP and DAD, the sequence was reversed: in S2814D+/+ sim, the increased diastolic Ca2+ leak elicited a rise in Ca2+ in the dyadic cleft through CICR, and hence in the cytosol by diffusion therein. This increase – favoured by the enhanced diastolic Ca2+ – was high enough to augment the forward NCX mode (I NCXdir) and to produce a membrane depolarization up to the level of fast Na+ channel opening (I Na) and SAP generation. The higher SR Ca2+ uptake in SD+/+/KOsim myocytes, which provoked a low diastolic Ca2+, prevented the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ necessary to enhance I NCXdir and the intracellular Na+ influx to depolarize the cell membrane up to the excitability threshold. Thus, the enhanced SR Ca2+ uptake in SD+/+/KOsim myocytes, precluded the triggering of a SAP, generating a DAD. This occurred in spite of a higher Ca2+ at the SR and the dyadic clefts in SD+/+/KOsim vs. S2814D+/+ sim myocyte. The inset in the figure shows an expanded image of the main events that explain the different behaviour of S2814D+/+ sim and SD+/+/KOsim. Cytosolic Ca2+ levels and I NCXdir decisive participation in the type of arrhythmic events (SAPs or DADs) was confirmed by the reproduction of SAPs in SD+/+/KOsim, after introducing a threshold intracellular [Ca2+]i pulse (2 nM Ca2+ in cytosol for 12 ms), during the end diastolic period of the last stimulated beat (not shown).

Figure 10. Model simulation of experimental results .

A, model‐derived time course of action potential, intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transient ([Ca2+]SR), intracellular cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient ([Ca2+]i), Ca2+ in dyadic cleft 1 and 2, and developed force (F m) in WT, S2814D+/+, PLNKO and SD+/+/KO myocyte simulations. B, intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in the human myocyte model when the different characteristics of mouse myocytes were simulated (WTsim, S2814D+/+ sim, PLKOsim, SD+/+/KOsim). Notice the similarity with the behaviour of the experimental counterparts (see Fig. 1). C, relationship between diastolic Ca2+ leak (I leak) and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ content ([Ca2+]SR), in the different strains simulated. Note that for a given I leak, SR Ca2+ load is lower in S2814D+/+ sim and SD+/+/KOsim myocytes than in WTsim and PLNKOsim myocytes, which is due to the higher open probability of RyR2 in these myocytes

Figure 11. Model simulation of experimental arrhythmias under stress conditions .

Aa and b, last steady state beat at high [Ca2+] before stopping high stimulation frequency (ST) and the events that followed after stopping stimulation, in simulated S2814D+/+ (S2814D+/+ sim) and SD+/+/KO (SD+/+/KOsim) cardiac myocytes. A train of spontaneous action potentials (SAP) immediately appeared after stopping stimulation in S2814D+/+ sim myocytes. In contrast, SD+/+/KOsim myocytes did not develop SAP but delayed afterdepolarizations (DAD). Ac–f, expanded view of different events of the last steady state beat and the first spontaneous events at high [Ca2+] after stopping stimulation. Ac and d, triggered AP after ST and SAP or DAD (V m), and intracellular Ca2+ in the dyadic clefts [Ca]c1 and [Ca]c2, in the cytosol [Ca]i and the SR ([Ca]SR. Ae and f, SR Ca2+ uptake (I up), SR Ca2+ release (I rel), NCX current (I NCX), L‐type Ca2+ current (I CaL) and Na+ current (I Na). Notice the higher SR Ca2+ content and uptake and the higher peak Ca2+ in the clefts in SD+/+/KOsim vs. S2814D+/+ sim. The inset to the right shows an amplified view of the main events leading to either SAP or DAD. The relative low rate of SR Ca2+ uptake (full line) (I up) in S2814D+/+ sim allows an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ that activates NCXdir to a level that triggers a SAP. In contrast, the higher SR Ca2+ uptake rate in SD+/+/KOsim precludes the necessary increase in cytosolic Ca2+ to activate NCXdir and reach the membrane depolarization threshold to trigger a SAP. Note the similitude of the cytosolic Ca2+ profile of S2814D+/+ sim in the middle panel of the inset with the displayed profile of Fig. 7 A (middle panel). B, action potential and Ca2+ transients during ISO stimulation in WT, S2814D+/+ sim and SD+/+/KO sim showing no spontaneous events in WT, SAPs and DADs in S2814D+/+, and EADs in SD+/+/KOsim. Note that whereas WT and SD+/+/KO sim myocytes followed the stimulation frequency (vertical mark, ST), in the S2814D+/+ sim myocyte, a SAP appeared before the triggered stimulus.

Since in the in vivo experiments we applied an adrenergic challenge, we also modelled the effects of β‐adrenergic stimulation in a cardiomyocyte, by simulating the effect of 100 nm isoproterenol (Iso) on the different Ca2+ fluxes, based on experimental data as previously described (Negroni et al. 2015). Figure 11 B shows that when the model was submitted to a β‐adrenergic challenge, S2814D+/+ sim cells displayed arrhythmic events which were not observed either in the wild‐type simulated model or in SD+/+/KOsim myocytes. Thus, although the in vivo conditions can be only partially mimicked in an isolated cell, the model reproduced the experimental finding that ablation of PLN prevents the arrhythmogenic effect of an adrenergic challenge.

We then asked the model the outcome of gradually increasing SR Ca2+ uptake from basal to PLNKO levels, on the occurrence of triggered SAP in a cardiomyocyte which simulates the characteristics of S2814D+/+ cells. Since 100% PLN ablation produces 25% decrease in RyR2 expression (Chu et al. 1998), we simulated the gradual proportional decrease in RyR2 expression as a reduction in RyR2 conductance, for each incremental increase in PLN suppression. Table 3A depicts the results of this type of simulation. An increase in SERCA2a activity as modest as 10% was sufficient to drastically reduce SAPs from 21 to 5. When the effect of PLN ablation on RyR2 abundance (conductance) was not applied (Table 3B), the SR Ca2+ uptake required to reduce SAP, increased to 15%. This finding suggests that the reduction of RyR2 expression when the true SD+/+/KO myocyte was simulated plays a negligible role in arrhythmia decline. Interestingly, the model shows that spontaneous beats declined with the gradual increase in SERCA2a activity despite the gradual rise of SR Ca2+ content. These results support the experimental findings indicating that the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake protects against triggered arrhythmias. Moreover, the model predicts that SR Ca2+ uptake below basal levels (Table 3B) also rescues from arrhythmic events, in agreement with previous experiments by Stokke et al. (2010). These authors demonstrated that reduction of SERCA2a abundance decreases the propensity for Ca2+ wave development in cardiomyocytes. The most probable reason for these results is the decrease in SR Ca2+ content produced by decreasing SR Ca2+ uptake (Stokke et al. 2010). Notice in Table 3B that the decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake was associated with a decrease in I NCX and the level of membrane depolarization (V m,max) necessary to reach the excitability threshold. Either no changes or increases in SR Ca2+ uptake up to 10% were associated with an increase in I NCX and in V m,max and a maximum increase in SAP frequency. Further increases in SR Ca2+ uptake up to 30% diminished the frequency of SAP, in spite of the increase in I NCX. The increase in I NCX allows membrane depolarization to reach the threshold to produce a single SAP. In the following spontaneous events, there was a progressive decrease in I NCX (data not shown) to values which prevents the occurrence of successive SAPs, inducing only DADs. Thereafter, I NCX as well as V m,max fluctuated within values lower than those required for a SAP to occur.

Table 3.

Effect of percent changes in SERCA2a Ca2+ uptake on arrhythmia generation by enhancing RyR2 conductivity as in S2814D+/+ myocytes

| A. Progressive increase in SERCA2a Ca2+ uptake associated with a ‘compensatory’ prorated decrease in RyR2 conductance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % participation | SERCA2a activity | RyR2 Ca2+ conductance | [Ca2+]SR (μm) | |||

| of PLNKO | (% change vs. WT) | (% increase vs. WT) | (last st. beat) | I leak (μm s−1) | SAP | DAD/EAD |

| 0 (S2814D+/+) | 0 | 50.00 | 3726 | 20.52 | 21 | 0 / 0 |

| 10 | 5 | 46.25 | 3909 | 21.43 | 21 | 0 / 0 |

| 20 | 10 | 42.50 | 4091 | 22.12 | 5 | 3 / 0 |

| 30 | 15 | 38.75 | 4271 | 22.85 | 2 | 3 / 0 |

| 40 | 20 | 35.00 | 4447 | 23.60 | 1 | 3 / 0 |

| 50 | 25 | 31.25 | 4619 | 24.44 | 1 | 3 / 0 |

| 60 | 30 | 27.50 | 4787 | 25.22 | 1 | 3 / 0 |

| 70 | 35 | 23.75 | 4950 | 26.34 | 0 | 3 / 1 |

| 80 | 40 | 20.00 | 5106 | 27.65 | 0 | 3 / 1 |

| 90 | 45 | 16.25 | 5256 | 29.53 | 0 | 3 / 1 |

| 100 (SD+/+/KO) | 50 | 12.50 | 5399 | 32.43 | 0 | 4 / 0 |

| B. Progressive increase and decrease in SERCA2a Ca2+ uptake without ‘compensatory’ changes in RyR2 conductance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERCA2a activity | [Ca2+]SR (μm) | |||||

| (% change vs. WT) | (last st. beat) | I leak (μm s−1) | I NCX (μA μF−1) | V m,max (mV) | SAP | DAD/EAD |

| −40 | 2693 | 14.42 | 0.093 | −90.0 | 0 | 0 / 0 |

| −35 | 2798 | 14.82 | 0.090 | −90.0 | 0 | 0 / 0 |

| −30 | 2911 | 15.48 | 1.602 | −76.6 | 0 | 1 / 0 |

| −25 | 3035 | 16.07 | 1.760 | −75.1 | 0 | 1 / 0 |

| −20 | 3168 | 16.82 | 1.909 | −73.6 | 0 | 1 / 0 |

| −15 | 3306 | 17.65 | 2.054 | −71.9 | 0 | 1 / 0 |

| −10 | 3446 | 18.67 | 2.193 | −70.0 | 0 | 2 / 0 |

| −5 | 3587 | 19.57 | 2.323 | −67.5 | 0 | 2 / 0 |

| 0 | 3726 | 20.52 | 2.438 | Threshold* | 21 | 0 / 0 |

| 5 | 3860 | 21.70 | 2.537 | Threshold* | 21 | 0 / 0 |

| 10 | 3988 | 22.85 | 2.618 | Threshold* | 21 | 0 / 0 |

| 15 | 4108 | 24.07 | 2.681 | Threshold* | 2 | 3 / 0 |

| 20 | 4218 | 25.41 | 2.725 | Threshold* | 2 | 3 / 0 |

| 25 | 4318 | 26.87 | 2.752 | Threshold* | 1 | 3 / 0 |

| 30 | 4407 | 28.61 | 2.759 | Threshold* | 1 | 3 / 0 |

| 35 | 4482 | 30.77 | 2.257 | −69.1 | 0 | 3 / 2 |

| 40 | 4540 | 34.07 | 2.290 | −68.6 | 0 | 4 / 2 |

| 45 | 4578 | 39.39 | 2.222 | −69.8 | 0 | 4 / 2 |

| 50 | 4586 | 48.33 | 2.404 | −65.7 | 0 | 4 / 0 |

A, enhanced RyR2 open probability was simulated by increasing RyR2 Ca2+ conductance and PLN inhibition by increasing SERCA2a activity. Data are expressed as percentage change with respect to WT. Simulations span from S2814D+/+ to SD+/+/KO conditions. The decrease in expression of RyR2 in PLNKO (Chu et al. 1998) was mimicked, i.e. the 25% decrease in expression of RyR2 in PLNKO was prorated according to the proportion of PLN ablation. The conditions of S2814D+/+ (first row) and of SD+/+KO (last row), were used in the experimental protocol shown in Fig. 11. B, SERCA2a activity was stepwise increased and decreased above and below basal levels, respectively. Compensatory modifications of RyR2 were not performed. Therefore, enhanced RyR2 open probability (increased RyR2 Ca2+ conductance) was kept augmented by 50% above basal levels all over the range of SERCA2a activities explored. SAP, spontaneous action potentials; DAD, delayed afterdepolarization; EAD, early afterdepolarization; I NCX, maximum Ca2+ current by the forward mode of the NCX. V m,max, maximum membrane potential depolarization produced by I NCX current. *Sodium channel threshold was reached at −55.6 mV. Last st. beat: last stimulated beat.

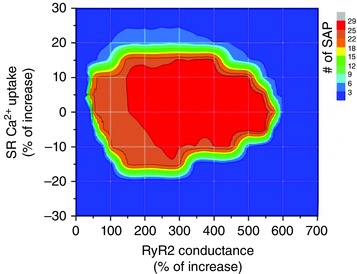

Finally we modelled the effect of either increasing or decreasing SR Ca2+ uptake as shown in Table 3B, at different percent increases of SR Ca2+ leak (RyR2 conductance). This approach gave rise to the data depicted in the heat plot of Figure 12. The figure indicates that the arrhythmogenic zone extends from an increase in RyR2 conductance of approximately 0.5 up to 6 times over basal values, with different levels of arrhythmogenicity. The hot arrhythmogenic area starts at RyR2 conductances higher than 150%. Values of RyR2 conductance higher than 570% abruptly lessen SAP occurrence. This reduction can be attributed to the reduced SR Ca2+ content due to the increase in RyR2 conductance. Indeed with an increased RyR2 conductance of 570%, SR Ca2+ content diminished by 65% with respect to no increase in RyR2 conductance. The arrhythmic effect of increasing RyR2 conductance was completely cancelled by either decreasing or increasing SR Ca2+ uptake below and above basal values, respectively. As previously discussed, the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake provoked a decrease in cytosolic Ca2+ during diastole, preventing the enhancement of Ca2+ efflux through the NCXdir and the required Na+ influx to depolarize the cell membrane up to the excitability threshold (see Fig. 11 and Table 3B), in accordance with our experimental conclusions. Conversely, the decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake reduced SR Ca2+ content and leak (see Table 3B), preventing the necessary Ca2+ efflux and Na+ influx from reaching the excitability threshold (see Table 3B).

Figure 12. 2D‐plot showing SAP occurrence as a function of increased or decreased SR Ca2+ uptake and RyR2 increase in conductance .

The figure indicates different levels of arrhythmogenicity. The higher arrhytmogenic area, in red, extends from an increase in RyR2 conductance between approximately 150% and 550% and from increased or decreased SR Ca2+ uptake that varies from a maximum of ±15% at the lower RyR2 conductances, to ±5% at the highest RyR2 increases in conductance (550%). Higher increases in RyR2 conductances diminished the arrhythmia propensity due the decreases in SR Ca2+ content.

Taken together, the model shows that, similarly to the experimental results, Ca2+‐triggered arrhythmias due to an increase in SR Ca2+ leak (S2814D+/+ sim mice) may be rescued by an increase in SR Ca2+ uptake (SD+/+/KO sim). The model further shows that a decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake can rescue from arrhythmias triggered by an increase in SR Ca2+ leak, offering an explanation for previous contradictory results (Stokke et al. 2010). Thus, the model indicates that the success of varying SR Ca2+ uptake in rescuing the propensity for arrhythmic events rests on a tight balance between the degree of Ca2+ leak and uptake by the SR.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that PLN ablation reduces the propensity to ventricular arrhythmias caused by constitutive pseudo‐phosphorylation of the Ser2814 site on RyR2, both at the intact animal and the isolated perfused heart levels. Given the correlation between Ca2+ waves in single cells and the occurrence of arrhythmias, our results also suggest that the underlying mechanism by which PLN ablation blocks arrhythmias in S2814D+/+ animals is the abortion of fully propagating SR Ca2+ waves which were transformed into non‐propagating, non‐arrhythmogenic events, e.g. mini‐waves. The clinical relevance of these findings is obvious with respect to arrhythmias in HF and reperfusion arrhythmias, since CaMKII expression, activity and phosphorylation of RyR2 at S2814 are all enhanced in patients and animals with HF (Ai et al. 2005; Sossalla et al. 2010) and during reperfusion after cardiac ischaemia (Vittone et al. 2002; Salas et al. 2010; Di Carlo et al. 2014).

Previous experiments in the CaMKII phosphomimetic S2814D+/+ mice revealed the central role played by CaMKII phosphorylation of RyR2 in causing stress‐induced arrhythmogenic events at the whole‐animal level (van Oort et al. 2010). In the present work these events were associated with an increase in SR Ca2+ sparks and leak at the myocyte level (van Oort et al. 2010). We further showed that S2814D+/+ mice increased not only Ca2+ spark frequency but also SR arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves, providing a mechanistic link between CaMKII‐dependent RyR2 phosphorylation and ventricular Ca2+ arrhythmias in S2814D+/+ mice. The increase in SR Ca2+ waves would lead to enhanced Ca2+ extrusion via the electrogenic NCX. This electrogenic transport generates a depolarizing current (I ti or transient inward current), which, when sufficiently large, leads to delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and potentially triggers ectopic APs and ventricular arrhythmias (Spencer & Sham, 2003; Fujiwara et al. 2008). The present experiments further showed that, as expected, the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake produced by PLN ablation dramatically enhanced SR Ca2+ leak and sparks in SD+/+/KO myocytes. In spite of this increase, Ca2+ waves were significantly reduced. An increase in SR Ca2+ leak associated with a decrease in propagating Ca2+ waves indicates a limitation in cytosolic Ca2+ diffusion. Our findings clearly show that PLN ablation interrupts cell‐wide propagating Ca2+ waves, converting them into non‐propagated events, like mini‐waves or groups of Ca2+ sparks. These results support the conclusion that by increasing SR Ca2+ uptake, PLN ablation decreases cytosolic Ca2+, which would increase cytosolic Ca2+ buffer capacity, hampering Ca2+ wave propagation and preventing the arrhythmogenic susceptibility produced by constitutive CaMKII‐dependent pseudo‐phosphorylation of the RyR2‐Ser2814 site. Further support to this idea is given by the experiments in which decreasing SR Ca2+ uptake by the SERCA2a inhibitor, CPA, converts non‐propagating mini‐waves into full propagating Ca2+ waves.

One could argue that since PLNKO myocytes contain fewer ryanodine receptors than WT cells (approximately 25%; Chu et al. 1998), the decrease in arrhythmogenic events observed in SD+/+/KO mice can be at least partially explained by this reduction in SR Ca2+ channels. However, the present and other studies (Santana et al. 1997; Huser et al. 1998) also showed that Ca2+ spark frequency, Ca2+ spark amplitude and SR Ca2+ leak, are higher in PLNKO and SD+/+/KO than in WT and S2814D+/+ mice, a result that indicates that the decrease in SR Ca2+ waves observed in SD+/+/KO mice can barely be attributed to the diminished RyR2 abundance.

Most of our studies were performed in SD+/+/KO mice obtained from homozygous S2814D+/+ and PLNKO mice. This model enabled us to elucidate the specific effects of PLN ablation on the enhanced SR Ca2+ leak typical of RyR2 phosphorylation. We are aware, however, that SD+/+/KO mice represent a rather unique situation in which RyR2 is maximally and permanently phosphorylated by CaMKII at the S2814 site and SR Ca2+ uptake is increased up to the level produced by PLN ablation. This is unlikely to be the situation in the diseases in which CaMKII increases its activity, like ischaemia–reperfusion injury or heart failure. For instance, we know that RyR2 and PLN are phosphorylated by CaMKII only for the first few minutes of reperfusion after ischaemia (Vittone et al. 2002; Salas et al. 2010; Di Carlo et al. 2014). Also, in patients or animals with heart failure, the level of Ser2814 phosphorylation increased by approximately 50–100 % (Ai et al. 2005; Chelu et al. 2009; Sossalla et al. 2010). Previous experiments described that heterozygous S2814D+/− mice have an arrhythmic pattern similar to homozygous mice (van Oort et al. 2010). Similar results were observed by us in our ex vivo experiments in the intact heart (Fig. 4). In these experiments, PLN ablation was able to rescue the arrhythmic pattern of heterozygous S2814D+/− mice, suggesting that our data may be also relevant as a model of RyR2 phosphorylation observed in diseases in which CaMKII‐dependent RyR2 phosphorylation is less germane than in S2814D+/+ mice.

Whereas the crucial role of increasing RyR2 activity in the development of triggered arrhythmias is rather obvious, the role of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake has remained uncertain and there is evidence describing both beneficial and detrimental effects of different manoeuvres used to increase SR Ca2+ uptake. For instance, and in full agreement with our present findings, it has been shown that improving intracellular Ca2+ handling by overexpression of SERCA2a restores contractile function and reduces ventricular arrhythmias in different models of ischaemia–reperfusion injury (del Monte et al. 2004; Prunier et al. 2008). Moreover, SERCA2a overexpression decreases the incidence of aftercontractions in rabbit ventricular myocytes (Davia et al. 2001). Conversely, a recent paper showed that super inhibition of SERCA2a by the human mutation of PLN (R25C‐PLN) is arrhythmogenic (Liu et al. 2015). In conflict with these findings, there is also evidence showing that diminishing SR Ca2+ uptake contributes to abrogation of triggered arrhythmias (Lukyanenko et al. 1999; Landgraf et al. 2004). Similarly, reduction of SERCA2a abundance decreases the propensity for Ca2+ wave development and ventricular extrasystoles (Stokke et al. 2010). The discrepancy of these results may lie, at least in part, in the fact that the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake may regulate SR Ca2+ wave development and the possibility of arrhythmia generation in different and even opposite ways: increasing SR Ca2+ leak through the increase in SR Ca2+ content favours the likelihood of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves. Moreover, experimental evidence indicates that increasing local SR Ca2+ uptake by SERCA2a may facilitate wave transmission via luminal sensitization of RyR2 (the ‘fire–diffuse–uptake–fire’ mechanism) (Maxwell & Blatter, 2012). However, other experiments indicate that increasing SR Ca2+ uptake hinders Ca2+ wave propagation by altering cytosolic Ca2+ buffer capacity (Huser et al. 1998; Bai et al. 2013). These mechanisms may not be necessarily exclusive, making the resultant outcome difficult to predict. To address this problem, we utilized an already proven integrated human cardiac myocyte model to mimic the experimental situation of S2814D+/+ and SD+/+/KO cardiac cells. The model was not only able to reproduce the functional behaviour of isolated myocytes under basal conditions, but also to replicate the development of spontaneous events, when either S2814D+/+ myocytes or intact mice were submitted to stress. Furthermore, the simulation of PLN ablation was able to rescue the arrhythmogenic propensity of S2814D+/+ myocytes, i.e. the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake rescued the arrhythmic consequences associated with enhancement of SR Ca2+ leak due to increases in the RyR2 conductance. According to our model, the increase in SR Ca2+ uptake is able to rescue the propensity to arrhythmias evoked by a leaky RyR2, by decreasing diastolic Ca2+ and therefore limiting the Ca2+ efflux through the NCXdir. This would in turn reduce the Na+ influx necessary to depolarize the cell membrane up to the excitability threshold. The model provides in addition a much‐needed understanding for the disparate results seen in the literature, not only those which demonstrated, in agreement with our results, that overexpressing SERCA2a decreased the probability of aftercontractions or of reperfusion arrhythmias (Davia et al. 2001, del Monte et al. 2004, Prunier et al. 2008), but also those showing that the decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake can also rescue from triggered arrhythmias (Stokke et al. 2010). Our model supports the view of Stokke et al. indicating that a main cause of the decrease in arrhythmogenic Ca2+ wave development after decreasing SR Ca2+ uptake rests on a decrease in SR Ca2+ load, i.e. the decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake, by decreasing SR Ca2+ content diminishes SR Ca2+ leak to levels below those required for enhancing NCXdir and the Na+ influx necessary to depolarize the cell membrane and to evoke an ectopic beat as depicted in Table 3B.

Limitations of the present study

Our experimental model is limited by the rather unique situation in which RyR2 is maximally and permanently pseudo‐phosphorylated by CaMKII at the S2814 site and SR Ca2+ uptake is increased at the level produced by PLN ablation. We addressed this limitation by using heterozygous S2814D+/− mice and through the development of a human myocyte model that simulates our experimental conditions and allows predicting the effects of different degrees of increases in SR Ca2+ uptake on the arrhythmogenic pattern produced by the RyR2 enhanced conductance.

Regarding the mathematical model limitations, we acknowledge that although it is true that the incorporation of two dyadic clefts (DC1 and DC2), representing both the L‐type Ca2+ channel (LCC) and regenerative RyR2 activation, provides better insight into the CICR mechanism at the dyadic cleft, the model does not contemplate Ca2+ propagation throughout the myocyte by the regenerative mechanism of CICR. However, the effects of increasing SR Ca2+ uptake on the abrogation of the full propagation of Ca2+ waves observed experimentally has its model counterpart represented by the insufficient Ca2+ diffusion from the dyadic cleft to the cytosol and the decrease in diastolic Ca2+, both produced by the enhanced I up. Thus, our simplified representation of CRU activation, involving Ca2+ propagation from DC1 to DC2, did not affect model reproduction of the experimental SAPs in S2814D+/+ and DADs in SD+/+/KO double mutants. Another potential limitation of the work is that a human myocyte model, and not a mouse model, was used to simulate experimental results in transgenic mice. This apparent limitation does not seem to involve large discrepancies in model structure, as the general approach used in the most representative mouse model (Bondarenko et al. 2004) is similar to the one presented here. Moreover, although ion current velocities are much shorter in the mouse model due to the elevated heart rate, their shapes are similar to the ones obtained with the present model (Ferreiro et al. 2012; Lascano et al. 2013). Furthermore, the ability of the human myocyte model to adequately reproduce transgenic mouse results would support the conclusions from experiments that cannot be performed in humans.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests or conflicts of interest with respect to this work.

Author contributions

This work was done in the laboratory of A.M. A.M, E.L., J.N., C.A.V. and J.P. were involved in the conception and design of the experiments and interpretation of the data. G.M., L.S., J.P., J.I.F., M.N.D.C. and P.C. performed the experiments and were involved in collection, analysis and interpretation of the data. D.F., C.A.V., L.S. and J.I.F. were involved in image analysis. P.G. and M.N.D.C. were involved in the histologic studies. D.S. and M.D.McC. were involved in mutant mice production. X.W. and E.G.K. provided the knock‐in mice and PLNKO mice, respectively, and were involved in critically revising the manuscript. J.N. and E.L. built the model and J.N. developed the MATLAB code. A.M., C.A.V., J.P., L.S. G.M., E.L. and J.N. were involved in drafting the article and/or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Council (Argentina), PIP0890 and PICT 2014–2524 to A.M., HL26057 and HL64018 (to L.K.), National Institutes of Health R01‐HL089598, R01‐HL091947, R01‐HL117641, and R41‐HL129570, the Muscular Dystrophy Association and the American Heart Association 13EIA14560061 (to X.H.T.W.) and K08‐HL130587 to M.D.McC.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank for technical assistance Drs Luciana Sapia and Omar Velez‐Rueda, Ms Mónica Rando, Ms Solange Bibé, Ms Helena Deutsch, Mr Omar Castillo and Mr Andrés Pinilla.

G. Mazzocchi and L. Sommese contributed equally to the present work.

References

- Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM & Pogwizd SM (2005). Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res 97, 1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Jones PP, Guo J, Zhong X, Clark RB, Zhou Q, Wang R, Vallmitjana A, Benitez R, Hove‐Madsen L, Semeniuk L, Guo A, Song LS, Duff HJ & Chen SR (2013). Phospholamban knockout breaks arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves and suppresses catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice. Circ Res 113, 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM (2014). Cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak: basis and roles in cardiac dysfunction. Annu Rev Physiol 76, 107–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko VE, Szigeti GP, Bett GC, Kim SJ & Rasmusson RL (2004). Computer model of action potential of mouse ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287, H1378–H1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]