Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–plasma membrane (PM) junctions are contact sites between the ER and the PM; the distance between the two organelles in the junctions is below 40 nm and the membranes are connected by protein tethers. A number of molecular tools and technical approaches have been recently developed to visualise, modify and characterise properties of ER–PM junctions. The junctions serve as the platforms for lipid exchange between the organelles and for cell signalling, notably Ca2+ and cAMP signalling. Vice versa, signalling events regulate the development and properties of the junctions. Two Ca2+‐dependent mechanisms of de novo formation of ER–PM junctions have been recently described and characterised. The junction‐forming proteins and lipids are currently the focus of vigorous investigation. Junctions can be relatively short‐lived and simple structures, forming and dissolving on the time scale of a few minutes. However, complex, sophisticated and multifunctional ER–PM junctions, capable of attracting numerous protein residents and other cellular organelles, have been described in some cell types. The road from simplicity to complexity, i.e. the transformation from simple ‘nascent’ ER–PM junctions to advanced stable multiorganellar complexes, is likely to become an attractive research avenue for current and future junctologists. Another area of considerable research interest is the downstream cellular processes that can be activated by specific local signalling events in the ER–PM junctions. Studies of the cell physiology and indeed pathophysiology of ER–PM junctions have already produced some surprising discoveries, likely to expand with advances in our understanding of these remarkable organellar contact sites.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- E‐Syts

extended synaptotagmins

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T‐cells

- Osh

oxysterol‐binding homology (proteins)

- ORP

oxysterol‐binding protein‐related protein

- PI4P

phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate

- PM

plasma membrane

- PMCA

plasma membrane Ca2+‐ATPase

- PTP1B

protein‐tyrosine phosphatase 1B

- SERCA

sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase

- SOCE

store‐operated Ca2+ entry

- STIM1

stromal interaction molecule 1

- TIRF

total internal reflection fluorescence (microscopy)

Introduction

An endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–plasma membrane (PM) junction is just one subtype of junction between cellular organelles. Junctions are also formed between mitochondria and ER (e.g. Rizzuto et al. 1998; Csordas et al. 2006; de Brito & Scorrano, 2008; Filadi et al. 2015), including both smooth and rough ER (Csordas et al. 2006); ER and endosomes (Eden et al. 2010; Friedman et al. 2013; Henne et al. 2015 b); ER and lysosomes (Kilpatrick et al. 2013; Fameli et al. 2014; Henne et al. 2015 b); ER and phagosomes (Nunes et al. 2012); Golgi apparatus and mitochondria (Dolman et al. 2005); and mitochondria and the PM (Park et al. 2001; Frieden et al. 2005; Perkins et al. 2010). Considerable progress has recently been achieved in the identification and characterisation of these junctions and their constituents (recently reviewed in Carrasco & Meyer, 2011; Prinz, 2014; Henne et al. 2015 a). This research area is undergoing a period of rapid growth. Considerable efforts are focused on clarifying the tethering structures and on understanding the general principles of junction formation, maturation and disassembly. Particularly impressive progress was achieved recently in characterising the ER–PM junctions, which will be discussed in this review.

Classical electron microscopy studies characterised specialised ER–PM junctions in skeletal muscle cells (Porter & Palade, 1957). Direct interaction of voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors at the junctions mediating stimulus–contraction coupling in skeletal muscle cells (recently reviewed by Takeshima et al. 2015) conferred physiological significance on these junctions and propelled them into the remit of general textbook knowledge. ER–PM junctions were also described in other primary cell types (e.g. Rosenbluth et al. 1962; Lur et al. 2009; Fernandez‐Busnadiego et al. 2015) and cell lines (e.g. Wu et al. 2006; Orci et al. 2009; Chang et al. 2013; Fernandez‐Busnadiego et al. 2015).

Studies of the ER–PM junctions recently attracted significant attention from cell biologists and became a fashionable, productive and a rather exciting research avenue. The reason for this was the discovery of the molecular mechanism of store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), a process dependent on the direct interaction of the ER resident protein stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) and the channel forming protein in the plasma membrane Orai1 (Liou et al. 2005; Roos et al. 2005; Feske et al. 2006; Luik et al. 2006; Prakriya et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006; Park et al. 2009; Yuan et al. 2009; Bergmeier et al. 2013). SOCE (initially termed capacitative Ca2+ entry; Putney, 2007) is one of the fundamental signalling and ion transport mechanisms operating in the majority of cell types (reviewed in Parekh & Putney, 2005; Putney, 2007; Hogan et al. 2010; Bergmeier et al. 2013); the realisation that it requires close contacts between the ER and the PM gave an impetus for studies of these junctions per se.

Visualising the localisation and structure of ER–PM junctions

Fortuitously, STIM1 (which made this research field so popular) also provides a tool for visualising ER–PM junctions. Upon ER Ca2+ store depletion, molecules of STIM1 oligomerise and translocate to ER–PM junctions where they can interact with phospholipids of the plasma membrane and Orai1 channels (Luik et al. 2006; Liou et al. 2007; Varnai et al. 2007; Walsh et al. 2010; Maleth et al. 2014). Oligomerised STIM1 is first diffusionally trapped in the ER–PM junctions due to its interaction with phospholipids, and then STIM1 interacts with Orai and also traps it in the ER–PM junctions (Liou et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2014); the latter process is regulated by septins (Sharma et al. 2013). In cells with depleted or partially depleted ER Ca2+ stores, STIM1 labelled with appropriate fluorescent proteins forms puncta in the vicinity of the plasma membrane, highlighting the ER–PM junctions. The distribution of the junctions can then be visualised using confocal or total internal reflection (TIRF) fluorescence microscopy. Using a similar approach, gold‐labelled antibodies against STIM1 (Orci et al. 2009) or STIM1 linked with horseradish peroxidase (Wu et al. 2006; Lur et al. 2009) can be used to reveal and characterise ER–PM junctions (specifically STIM1‐competent junctions) with the help of electron microscopy. Such studies revealed ER–PM junctions with inter‐membrane distances of 12–13 nm (Lur et al. 2009) and approximately 17 nm (Wu et al. 2006). Such distance allows direct STIM1–Orai1 interaction. To attain such close contact, ribosomes, which protrude from the ER surface by more than 20 nm (Lur et al. 2009), have to be removed from the ER region forming the junction. In some cells this is achieved by removing ribosomes specifically from the contact site, whilst the rest of the ER strand approaching the plasma membrane remains studded with ribosomes (Lur et al. 2009). In other cells types, relatively long and ribosome‐free smooth ER strands extend from rough ER, project to the plasma membrane and form junctions (Orci et al. 2009).

Recent studies from P. De Camilli's laboratory utilised cryo‐electron tomography to reveal the architecture and heterogeneity of ER–PM junctions (Fernandez‐Busnadiego et al. 2015) at EM level. This heterogeneity reflects two different mechanisms of junctional genesis: ER–PM junctions formed by STIM1 (exogenously expressed in these experiments) and its partners contained filamentous structures perpendicular to the organellar membranes, whilst junctions established due to the interaction of extended synaptotagmins (E‐Syts) with the plasma membrane contained an electron dense layer parallel to the ER and PM membranes (Fernandez‐Busnadiego et al. 2015). The distances between the membranes in E‐Syt‐dependent and STIM1‐mediated junctions were also different.

An elegant technique for visualising the ER–PM junctions was introduced by P. Varnai and colleagues in T. Balla's laboratory. This method involves rapamycin‐inducible bridge formation between fluorescently labelled ER and PM proteins. The co‐localisation of the fluorescence of the two markers reveals the ER–PM junctions. Using this approach the localisation of the ER–PM junctions can be determined without depletion of the ER Ca2+ store (Varnai et al. 2007). Importantly, the length of the linkers forming the bridge was variable; this ‘molecular ruler’ allowed estimation of the distances between membranes in the junctions as ‘larger than 8–9 nm but smaller than 12–14 nm’ (Varnai et al. 2007), corresponding well with the distances recorded in the EM study by G. Lur and colleagues (Lur et al. 2009). It is interesting to note that upon store depletion STIM1 decorated the same junctions as highlighted by rapamycin‐inducible bridges with long (approximately 14 nm intermembrane distance) linkers (Varnai et al. 2007). This strongly suggests that the endogenous junctions and the junctions revealed after ER Ca2+ store depletion are the same junctions (Varnai et al. 2007). Similar conclusions were also reached for another cell type (Chang et al. 2013).

One of the technical difficulties in studying the junctions is that the probes expressed in the cells to reveal the junctions (including STIM1 and the linkers) can excessively tether ER and PM and consequently modify the very junctions that they are designed to investigate or actually form additional junctions (Varnai et al. 2007; Lur et al. 2009). This problem was recently addressed by the laboratory of J. Liou. The probes, termed MAPPERs, were designed in such a way that they accumulate in junctions but do not modify the density of the junctions (Chang et al. 2013). The fluorescent component of the MAPPER (GFP) is localised in the ER lumen and allows visualisation of the ER–PM junctions using confocal or TIRF microscopy. Mini singlet oxygen generator (miniSOG)‐labelled MAPPER was successfully used to visualise ER–PM junctions using EM (Chang et al. 2013). It should perhaps be noted that even in the case of the MAPPERs it is difficult to exclude that these ER‐localised proteins capable of binding to the PM lipids will have no effect on the structure or dynamics of the ER–PM junctions in other cell types (or other experimental conditions). It is clear that careful controls, similar to those described by C. Chang and colleagues (Chang et al. 2013), are necessary to verify the suitability of the selected junction‐revealing probe for the planned experiments.

It is useful to note that whilst the distance between the ER and PM membrane in a junction is below the limit of resolution of visible‐light microscopy and even of modern super‐resolution optical systems, the lateral (parallel to PM) size of the junctions allows investigations into changes in size, shape, localisation and dynamics of junctions using high resolution optical fluorescence microscopy. Junctology is a particularly promising field for applications of super resolution optical microscopy (e.g. Chang et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2014; Okeke et al. 2016) and is likely to benefit from further development of this technology.

Formation, stability and dynamics of ER–PM junctions

Ca2+ signalling plays an important role in the formation of ER–PM junctions. Two modes of Ca2+ regulation have been described: M. Wu and colleagues from the laboratory of R. S. Lewis reported a significant (more than 60%) increase in the number of ER–PM junctions induced by the depletion of the ER Ca2+ store (Wu et al. 2006); later studies by the laboratories of P. De Camilli and J. Liou described ER–PM junction formation induced by increases in cytosolic Ca2+. Both laboratories independently discovered that the effect of cytosolic Ca2+ on junction formation is mediated by extended synaptotagmin 1 (E‐Syt1) (Chang et al. 2013; Giordano et al. 2013; Idevall‐Hagren et al. 2015). It is likely that both cytosolic Ca2+ rises and ER Ca2+ depletion can promote ER–PM junction formation. The common property of the two mechanisms is an increased ability of the tether protein (E‐Syt1 and STIM1 correspondingly) to interact with the plasma membrane. An important question is whether the two mechanisms form the same junctions. A number of studies suggested that all or at least the majority of ER–PM junctions are STIM1 competent (Varnai et al. 2007; Chang et al. 2013; Dingsdale et al. 2013); there is, however, convincing electron microscopy evidence that junctions formed by STIM1 and its interacting partners in the PM are structurally different from E‐Syt‐formed junctions (Fernandez‐Busnadiego et al. 2015). In other words different types of junctions are formed by different tethers and can coexist in the same cell. The heterogeneity of junctions is also supported by the study that described cAMP‐dependent accumulation of STIM1 in ER–PM junctions with different properties from the junctions revealed by Ca2+ store depletion (Tian et al. 2012). It is of course conceivable that the answer to this apparent controversy is cell‐type specificity. Importantly, in addition to cell lines this question should be systematically addressed using primary cell types and endogenous ER–PM junctions. Furthermore, whilst Ca2+‐dependent mechanisms of ER–PM junction formation have recently received significant attention, other mechanisms are likely to operate and form different ER–PM junctions, which await systematic characterisation.

Junctions can be labile or stable. It seems that at least in some cell types junctions are stationary and do not form (or dissolve) following short periods (tens of minutes) of Ca2+ store depletion or cytosolic Ca2+ elevation (Lur et al. 2009). Indeed classical ER–PM junctions first characterised in muscle cells (Porter & Palade, 1957) belong to this ‘stable’ category. An extended lifetime for a junction in a cell that does not undergo migration or frequent division could allow this junction to develop, specialise and attain significant complexity; this could involve attracting individual proteins (e.g. Ca2+ pumps), PM spanning complexes (e.g. intercellular junctions and focal adhesions) or even other cellular organelles (e.g. mitochondria). Such hypothetical evolution of the junctions from the nascent structures formed when the ER‐anchored tether protein first gingerly connects to its PM counterpart, to fully developed junctions surrounded by specific proteins, protein complexes and organelles (Abstract Figure) is an exciting area of investigation.

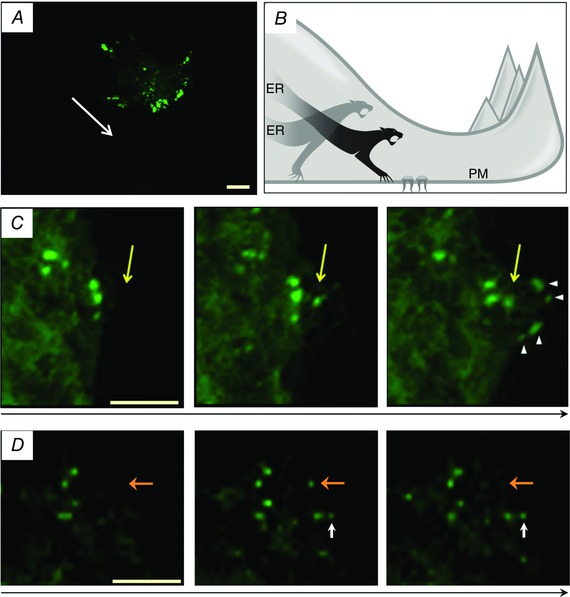

There are, however, junctions that are dynamic and cannot be stabilised until the behaviour of a cell changes. Examples of such ER–PM junctions can be found in migrating cells (Dingsdale et al. 2013). In these cells the distribution of ER–PM junctions is polarised with a high density of junctions found at the front (Fig. 1; Dingsdale et al. 2013; Tsai et al. 2014) in close proximity to focal adhesions and actin fibres (Dingsdale et al. 2013). Microtubule and STIM1‐dependent motoring of ER strands (Grigoriev et al. 2008) could play a role in the distribution of these junctions. It is plausible that local cytosolic Ca2+ signals generated near the leading edge (Wei et al. 2009; Tsai & Meyer, 2012; Tsai et al. 2014), and associated local ER Ca2+ depletions, determine the preferential formation of ER–PM junctions in this region. On the other hand the presence of STIM1‐competent ER–PM junctions in the immediate proximity to the migratory apparatus is likely to be important for sustaining Ca2+ signalling in this region and for cellular migration itself (Tsai & Meyer, 2012; Tsai et al. 2014; Okeke et al. 2016). The junctions at the front of migrating cells are dynamic structures undergoing saltatory process (Fig. 1) of formation (nearer the leading edge) and breakdown (behind the base of lamellipodium) (Dingsdale et al. 2013). The junctions at the tail of migrating cells are also dynamic and can undergo both rapid long‐distance sliding (interestingly sliding of the junctions was not observed at the leading edge) and dissolution (Dingsdale et al. 2013). Although local Ca2+ signals near the leading edge of migrating cells are likely to be important for the formation of the ER–PM junctions in this area, the exact role of this signalling modality has not been directly demonstrated and awaits further investigation. The lifetime of a junction at the leading edge of a rapidly moving cell is expected to be short; this poses a question as to the functionality of such junctions, namely, is the lifetime of these junctions sufficiently long to assemble useful signalling and transport components and fulfil the relevant physiological functions? This is another important unresolved question related to the evolution of ER–PM junctions and to the hierarchy of cellular functions that can be mediated by short‐lived junctions and by more stable junctions.

Figure 1. Dynamics of ER–PM junctions .

A, localisation of ER–PM junctions as revealed by accumulated yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)–STIM1 in a migrating cancer cell (PANC1 cell); a high density of the junctions (green) can be found near the leading edge. The direction of migration is indicated by a white arrow. Scale bar represents 10 μm. The panel is adapted (with modifications) from Dingsdale et al. (2013). B, artistic impression of saltatory formation of ER–PM junctions. Junctions do not slide along the plasma membrane; instead they ‘suddenly’ appear close to the leading edge in proximity to focal adhesions and disappear further behind the leading edge. C, appearance of ER–PM junctions at the front of a migrating PANC1 cell. The direction of cell migration is indicated by a long black arrow. Scale bar represents 10 μm. Yellow arrow shows a single junction that appears close to the leading edge, ahead of other junctions. This junction does not slide along with the migrating cell; instead an additional group of junctions (shown by arrowheads) form in front of the original junction as the cell moves further forward. The panel is adapted with modifications (only 3 out of 4 original images are shown) from (Dingsdale et al. 2013). D, turnover (appearance and disappearance) of ER–PM junctions at the leading edge of migrating cancer cells. The direction of cell migration is indicated by a long black arrow. Scale bar represents 5 μm. Orange arrow shows the junction that suddenly appears close to the leading edge (compare the central and the left panel) and then disappears before the next image (compare the central and the right panel). The white arrow shows the junction that appears and stabilises (increases in size and brightness) close to the leading edge of the cell. The panel is adapted (with modifications) from Dingsdale et al. (2013).

Signalling and transport processes in the ER–PM junctions

Some of the signalling and transport mechanisms associated with a STIM1‐competent ER–PM junction, and which are discussed in this section, are depicted in the Abstract Figure. As previously mentioned, ER–PM junctions serve as platforms for a fundamentally important signalling and transport process, SOCE, which is essential for replenishing Ca2+ in the endoplasmic reticulum. Ca2+ signalling, and particularly Ca2+ signalling in non‐excitable cells, relies on Ca2+ release from the ER via intracellular channels – InsP 3 receptors and ryanodine receptors. During normal physiological responses to hormones and neurotransmitters most of the released Ca2+ is usually returned to the stores by sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (SERCAs); however, part of this released Ca2+ is extruded from the cells by plasma membrane Ca2+‐ATPases (PMCAs). For example, in pancreatic acinar cells a single cytosolic Ca2+ transient induced by a physiological concentration of cholecystokinin results in the loss of approximately 100 μm of total cellular calcium (this corresponds to approximately 10% of the releasable ER Ca2+ store; Tepikin et al. 1992). To sustain long‐term Ca2+ signalling pancreatic acinar cells and many other cell types require an efficient replenishment mechanism, and SOCE fulfils this important function (reviewed in Parekh & Putney, 2005; Petersen & Tepikin, 2008). The strategic positioning of SERCA pumps in the ER–PM junctions increases the efficiency of Ca2+ store reloading (Manjarres et al. 2010; Manjarres et al. 2011; Alonso et al. 2012). Significant reloading of the Ca2+ store can occur after the recovery of the cytosolic Ca2+ to resting (or near‐resting) levels following the removal of a Ca2+‐releasing agonist (Mogami et al. 1998) or during interspike periods of Ca2+ oscillations (Park et al. 2000). It is conceivable that SERCA localised in the ER–PM junctions play a particularly important role in the reloading of the ER store in these conditions (i.e. in conditions of low cytosolic Ca2+ in the proximity to non‐junctional SERCAs). The reloading is also likely to be facilitated by local, STIM1‐dependent inhibition of PMCAs (Krapivinsky et al. 2011; Ritchie et al. 2012). In combination these mechanisms should prevent futile ATP consumption and maximise ER Ca2+ reloading.

Another fundamentally important function of SOCE is to maintain sufficient ER Ca2+ content to allow Ca2+‐dependent ER chaperones to fulfil their primary function of protein folding (reviewed in Wang et al. 2015). It is conceivable that ER Ca2+ sensors were developed for two purposes – to support protein folding in the ER and prevent termination of protein synthesis, and to maintain or support Ca2+ signalling (reviewed in Collins & Meyer, 2011). Two variants of STIM in eukaryotic cells, STIM1 and STIM2, have different affinities for Ca2+ (Liou et al. 2005; Brandman et al. 2007); this could reflect subspecialisation of these proteins for preventing protein unfolding in the ER and for sustaining Ca2+ signalling mediated by Ca2+ releases from the ER. The mechanism of SOCE activation requiring the direct interaction of ER Ca2+ sensors (STIM1 and STIM2) with channel‐forming PM resident proteins (Orai) assigns an important role to ER–PM junctions in the regulation of ER Ca2+ replenishment. Other STIM‐dependent SOCE mechanisms, particularly mechanisms involving transient receptor potential channels, have also been reported and associated with ER–PM junctions (e.g. Lee et al. 2010 b; de Souza et al. 2015; reviewed in Lee et al. 2010 a; Ong & Ambudkar, 2015).

It should be noted that aside from the important but rather subservient functions of supporting other signalling processes and maintaining ‘safe’ levels of Ca2+ in the cellular organelles, the ER–PM junctions can host specific signalling responses that are fundamental to cell fate. The importance of such junction‐specific signalling is well illustrated in the example of T‐cell activation. Upon stimulation of T‐cell receptors InsP 3 is generated and SOCE is activated as a consequence of ER Ca2+ depletion. In this case, however, the physiological response of T‐cells crucially depends on the prolonged Ca2+ elevation mediated by SOCE, requiring the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1; in other words, in T‐cells ER–PM junctions host signalling complexes that are responsible for the cytosolic Ca2+ rise and activation of the physiological response (Hogan et al. 2010; Shaw & Feske, 2012). The significant magnitude of SOCE in immune cells allowed recording of its electrophysiological equivalent, the Ca2+ release‐activated Ca2+ (CRAC) current (Hoth & Penner, 1992; Zweifach & Lewis, 1993). The prolonged Ca2+ elevation required for the activation of immune cells cannot be delivered by short‐term Ca2+ release events; instead it is the prolonged SOCE that plays the major signalling role (reviewed in Hogan et al. 2010; Shaw & Feske, 2012).

The specific and localised signalling responses in ER–PM junctions have been recently described by A. Parekh's laboratory. In this case the ER–PM junction not only serves as the site for interaction of STIM1 and Orai1 but also attracts the Ca2+‐binding protein calmodulin and its downstream effector, calcineurin, and forms a localised signalling complex (Kar et al. 2014; Kar & Parekh, 2015). The downstream cellular response (activation and translocation of nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (NFAT) followed by gene expression) could only be induced by Ca2+ responses mediated by the proteins localised in junctions or in immediate proximity to the junctions (within 20 nm); global Ca2+ responses of the same magnitude were unable to activate NFAT.

Junctional Ca2+ influx is not only important for cell physiology but also plays a role in cell damage. In non‐excitable cells SOCE is an important contributor to Ca2+ entry and excessive Ca2+ entry can induce Ca2+ toxicity; for example in pancreatic acinar cells STIM1‐ and Orai1‐dependent Ca2+ entry contributes to vacuolisation (Voronina et al. 2015) and cellular necrosis (Gerasimenko et al. 2013). In animal models of acute pancreatitis (a disease that is initiated by damage to the acinar cells) an inhibitor of STIM1‐ and Orai1‐mediated SOCE significantly reduced the severity of the disease (Wen et al. 2015).

Ca2+ signalling is not the only signalling modality localised in the ER–PM junctions. cAMP signalling cascades can also utilise the junctional complexes. STIM1‐dependent cAMP production was described by A. Hofer's laboratory and termed store‐operated cAMP signalling (SOcAMPS) (Lefkimmiatis et al. 2009); importantly for this review cAMP production required STIM1 accumulation in subplasmalemmal punctae, strongly suggesting that the process occurs in the ER–PM junctions (Lefkimmiatis et al. 2009). A later study identified adenylyl cyclases 3 (AC3) as the enzyme responsible for this STIM1‐dependent cAMP generation (Maiellaro et al. 2012). Another mechanism of cAMP production that utilises ER–PM junctions involves direct interaction of Ca2+‐activatable AC8 and Orai1 channels (Willoughby et al. 2012). This cAMP production mechanism is highly sensitive to SOCE and localised to subplasmalemmal Ca2+ microdomains (Willoughby et al. 2010, 2012).

Significant progress in identifying the mechanism of the formation of ER–PM junctions was attained due to experiments on yeast cells, where six proteins responsible for tethering of the two organelles (tricalbin1, 2 and 3; Scs2 and Scs3; Ist2) were characterised (Loewen et al. 2007; Manford et al. 2012). In the study by A. Manford and colleagues the ability of the ER‐resident phosphatase Sac1 to dephosphorylate phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate (PI4P) was used to verify the role of the tethering proteins and characterise their efficiency (Manford et al. 2012). The recent studies suggest that Sac1‐mediated regulation of PI4P in ER–PM junctions depends on the lipid transfer between PM and ER mediated by oxysterol‐binding homology (Osh) proteins in yeasts (Stefan et al. 2011; Moser von Filseck et al. 2015) and their analogues oxysterol‐binding protein related proteins (ORPs) in mammalian cells (Chung et al. 2015). The current model of the process enabling the ER‐resident phosphatase to modulate PM content of PI4P includes PI4P transfer across ER–PM junctions, mediated by Osh6p and Osh7P in yeasts (Moser von Filseck et al. 2015) or ORP5 and ORP8 in mammalian cells (Chung et al. 2015), followed by PI4P dephosphorylation in the ER by Sac1 (Chung et al. 2015; Moser von Filseck et al. 2015). Importantly in both yeasts and mammalian cells the PI4P transport from the PM to the ER is coupled to reverse transport of phosphatidylserine from the ER to the PM (Chung et al. 2015; Moser von Filseck et al. 2015). These findings highlight the importance of ER–PM junctions for lipid exchange, enabling phosphatidylserine delivery to the PM and the formation of a PI4P gradient between the ER and the PM (or, in other words, highlights the importance of ER–PM junctions to the lipid‐defined identity of these organelles). In addition to phosphatidylserine, ER–PM junctions support non‐vesicular transport of sterols from the ER to PM (Schulz et al. 2009; Gatta et al. 2015).

The ability of ER‐anchored protein‐tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) to interact with PM targets has been revealed by I. Anderie and colleagues in experiments utilising the bimolecular fluorescence complementation technique (Anderie et al. 2007). Furthermore, a study by F. Haj and colleagues demonstrated that a substrate‐trapping mutant of PTP1B was preferentially localised in cell–cell contact regions (Haj et al. 2012) suggesting that PTP1B‐competent ER–PM junctions are also localised in this region and serve as platforms for the phosphatase activity. Notably another mechanism for the delivery of substrates to the ER‐localised PTP1B involves endosomal transport and interactions between the ER and endosomes (e.g. Romsicki et al. 2004).

Recently two research groups independently and almost simultaneously characterised the role of E‐Syts in the formation of ER–PM junctions in mammalian cells (Chang et al. 2013; Giordano et al. 2013). E‐Syt1 is a Ca2+ binding protein and an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ results in the formation of ER–PM junctions (Giordano et al. 2013; Chang & Liou, 2015). Importantly, this initiates recruitment of the phosphatidylinositol transfer protein, Nir2, to the junctions (Chang et al. 2013). Nir2‐mediated lipid transport helps to replenish phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate (PIP2) in the PM that was depleted as a result of receptor stimulation and phospholipase C activation. A later study from the same group characterised Nir3, which also plays a role in junctional, non‐vesicular phosphatidylinositol transfer, and this role is particularly important at low levels of receptor activation (Chang & Liou, 2015). Finally, a recent study by Y. Kim and colleagues revealed Nir2‐mediated transfer of phosphatidic acid from the PM to the ER in ER–PM junctions supporting phosphatidylinositol synthesis in the ER (Kim et al. 2015).

One could suggest another hypothetical signalling mechanism related to ER–PM junctions. Functional relationships between mitochondria and SOCE have been described in a number of cell types (e.g. Hoth et al. 1997; Glitsch et al. 2002; Varadi et al. 2004; Barrow et al. 2008). Indeed SOCE, which develops in the ER–PM junctions as a result of STIM1 interaction with Orai1, depends on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and specifically on Ca2+ uptake mediated by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (Samanta et al. 2014). Mitochondrial Ca2+ accelerates the Krebs cycle (e.g. Hajnoczky et al. 1995; reviewed in Denton & McCormack, 1986), and this can result in acceleration of ROS production (reviewed in Brookes et al. 2004; Csordas & Hajnoczky, 2009; Adam‐Vizi & Starkov, 2010). One would expect that ER–PM junction‐associated ROS responses could influence other signalling cascades including Ca2+ signalling itself. Plasma membrane targeted ROS probes (Chvanov et al. 2015) or ROS sensors targeted specifically to ER–PM junctions could be used to directly test the existence of such localised ROS signalling.

The studies of the mechanisms responsible for the integration of Ca2+, cAMP and redox signalling in ER–PM junctions with lipid transport and lipid modifications is just one of the research avenues which is likely to undergo rapid development in the near future. The recent advances in optical super‐resolution microscopy, targeted fluorescent indicators and correlative light or electron microscopy will provide a technical base and an impetus for these studies.

Concluding remarks

The next few years are likely to reveal other types of interorganellar junctions and mechanisms for their formation, localisation and dissolution. It is probable that we will learn more about signalling reactions localised or initiated in the junctions. We hope that by analysing this new information we will understand the general principles of operation and underlying structure and functions of ER–PM junctions and of other interorganellar junctions. This research area is developing at a remarkable rate. One could therefore state that ‘The golden age of junctology is now’.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

The work of the laboratory is supported by the Medical Research Council (UK) grant MR/K012967/1, and the National Institute for Health Research (UK) grant to the NIHR Liverpool Pancreas Biomedical Research Unit. Emmanuel Okeke, Hayley Dingsdale and Tony Parker were supported by Wellcome Trust grants 092790/Z/10/Z, 086738/Z/08/A and 092792/Z/10/Z respectively.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to John Gavin for his help with Fig. 1 B.

Biographies

Emmanuel Okeke received his BSc at the University of Leicester (UK) and his PhD at the University of Liverpool (UK). He is currently a postdoctoral scientist in Duke University (USA).

Hayley Dingsdale received her BSc at the University of Manchester (UK) and her PhD at the University of Liverpool (UK). Her first postdoctoral position was in Duke University (USA). She is currently a postdoctoral scientist in Cardiff University (UK).

Tony Parker received his BSc at the University of Warwick (UK) and his PhD at the University of Liverpool (UK). He is currently a postdoctoral scientist in the University of Liverpool (UK).

Svetlana Voronina received her BSc at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (Russia) and her PhD at the University of Liverpool (UK). She is currently an experimental biophysicist in the University of Liverpool (UK).

Alexei Tepikin received his BSc at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (Russia) and his PhD at O.O. Bogomoletz Institute of Physiology (Ukraine). He is currently professor of physiology in the University of Liverpool (UK).

This review was presented at the symposium “Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms in Health and Disease”, which took place at the Gordon Research Conference on Calcium Signalling ‐ Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms in Health and Disease in Maine, USA, 7–12 June, 2015.

References

- Adam‐Vizi V & Starkov AA (2010). Calcium and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation: how to read the facts. J Alzheimers Dis 20 Suppl 2, S413–S426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso MT, Manjarres IM & Garcia‐Sancho J (2012). Privileged coupling between Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane store‐operated Ca2+ channels and the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump. Mol Cell Endocrinol 353, 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderie I, Schulz I & Schmid A (2007). Direct interaction between ER membrane‐bound PTP1B and its plasma membrane‐anchored targets. Cell Signal 19, 582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow SL, Voronina SG, da Silva Xavier G, Chvanov MA, Longbottom RE, Gerasimenko OV, Petersen OH, Rutter GA & Tepikin AV (2008). ATP depletion inhibits Ca2+ release, influx and extrusion in pancreatic acinar cells but not pathological Ca2+ responses induced by bile. Pflugers Arch 455, 1025–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier W, Weidinger C, Zee I & Feske S (2013). Emerging roles of store‐operated Ca2+ entry through STIM and ORAI proteins in immunity, hemostasis and cancer. Channels 7, 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O, Liou J, Park WS & Meyer T (2007). STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell 131, 1327–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW & Sheu SS (2004). Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love‐hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287, C817–C833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco S & Meyer T (2011). STIM proteins and the endoplasmic reticulum‐plasma membrane junctions. Annu Rev Biochem 80, 973–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CL, Hsieh TS, Yang TT, Rothberg KG, Azizoglu DB, Volk E, Liao JC & Liou J (2013). Feedback regulation of receptor‐induced Ca2+ signaling mediated by E‐Syt1 and Nir2 at endoplasmic reticulum‐plasma membrane junctions. Cell Rep 5, 813–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CL & Liou J (2015). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate homeostasis regulated by Nir2 and Nir3 proteins at endoplasmic reticulum‐plasma membrane Junctions. J Biol Chem 290, 14289–14301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Torta F, Masai K, Lucast L, Czapla H, Tanner LB, Narayanaswamy P, Wenk MR, Nakatsu F & De Camilli P (2015). PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5‐ and ORP8‐mediated ER‐plasma membrane contacts. Science 349, 428–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chvanov M, Huang W, Jin T, Wen L, Armstrong J, Elliot V, Alston B, Burdyga A, Criddle DN, Sutton R & Tepikin AV (2015). Novel lipophilic probe for detecting near‐membrane reactive oxygen species responses and its application for studies of pancreatic acinar cells: effects of pyocyanin and L‐ornithine. Antioxid Redox Signal 22, 451–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SR & Meyer T (2011). Evolutionary origins of STIM1 and STIM2 within ancient Ca2+ signaling systems. Trends Cell Biol 21, 202–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas G & Hajnoczky G (2009). SR/ER‐mitochondrial local communication: calcium and ROS. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787, 1352–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA & Hajnoczky G (2006). Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol 174, 915–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brito OM & Scorrano L (2008). Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 456, 605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza LB, Ong HL, Liu X & Ambudkar IS (2015). Fast endocytic recycling determines TRPC1‐STIM1 clustering in ER‐PM junctions and plasma membrane function of the channel. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853, 2709–2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton RM & McCormack JG (1986). The calcium sensitive dehydrogenases of vertebrate mitochondria. Cell Calcium 7, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingsdale H, Okeke E, Awais M, Haynes L, Criddle DN, Sutton R & Tepikin AV (2013). Saltatory formation, sliding and dissolution of ER‐PM junctions in migrating cancer cells. Biochem J 451, 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolman NJ, Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Voronina SG, Petersen OH & Tepikin AV (2005). Stable Golgi‐mitochondria complexes and formation of Golgi Ca2+ gradients in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem 280, 15794–15799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden ER, White IJ, Tsapara A & Futter CE (2010). Membrane contacts between endosomes and ER provide sites for PTP1B‐epidermal growth factor receptor interaction. Nat Cell Biol 12, 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fameli N, Ogunbayo OA, van Breemen C & Evans AM (2014). Cytoplasmic nanojunctions between lysosomes and sarcoplasmic reticulum are required for specific calcium signaling. F1000Res 3, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Busnadiego R, Saheki Y & De Camilli P (2015). Three‐dimensional architecture of extended synaptotagmin‐mediated endoplasmic reticulum‐plasma membrane contact sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E2004–E2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M & Rao A (2006). A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A, Pozzan T & Pizzo P (2015). Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum‐mitochondria coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E2174–E2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden M, Arnaudeau S, Castelbou C & Demaurex N (2005). Subplasmalemmal mitochondria modulate the activity of plasma membrane Ca2+‐ATPases. J Biol Chem 280, 43198–43208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JR, Dibenedetto JR, West M, Rowland AA & Voeltz GK (2013). Endoplasmic reticulum‐endosome contact increases as endosomes traffic and mature. Mol Biol Cell 24, 1030–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatta AT, Wong LH, Sere YY, Calderon‐Norena DM, Cockcroft S, Menon AK & Levine TP (2015). A new family of StART domain proteins at membrane contact sites has a role in ER‐PM sterol transport. eLife 4, doi: 10.7554/eLife.07253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko JV, Gryshchenko O, Ferdek PE, Stapleton E, Hebert TO, Bychkova S, Peng S, Begg M, Gerasimenko OV & Petersen OH (2013). Ca2+ release‐activated Ca2+ channel blockade as a potential tool in antipancreatitis therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 13186–13191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano F, Saheki Y, Idevall‐Hagren O, Colombo SF, Pirruccello M, Milosevic I, Gracheva EO, Bagriantsev SN, Borgese N & De Camilli P (2013). PI(4,5)P2‐dependent and Ca2+‐regulated ER‐PM interactions mediated by the extended synaptotagmins. Cell 153, 1494–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch MD, Bakowski D & Parekh AB (2002). Store‐operated Ca2+ entry depends on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. EMBO J 21, 6744–6754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriev I, Gouveia SM, van der Vaart B, Demmers J, Smyth JT, Honnappa S, Splinter D, Steinmetz MO, Putney JW Jr, Hoogenraad CC & Akhmanova A (2008). STIM1 is a MT‐plus‐end‐tracking protein involved in remodeling of the ER. Curr Biol 18, 177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj FG, Sabet O, Kinkhabwala A, Wimmer‐Kleikamp S, Roukos V, Han HM, Grabenbauer M, Bierbaum M, Antony C, Neel BG & Bastiaens PI (2012). Regulation of signaling at regions of cell‐cell contact by endoplasmic reticulum‐bound protein‐tyrosine phosphatase 1B. PloS One 7, e36633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky G, Robb‐Gaspers LD, Seitz MB & Thomas AP (1995). Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell 82, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne WM, Liou J & Emr SD (2015. a). Molecular mechanisms of inter‐organelle ER‐PM contact sites. Curr Opin Cell Biol 35, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne WM, Zhu L, Balogi Z, Stefan C, Pleiss JA & Emr SD (2015. b). Mdm1/Snx13 is a novel ER‐endolysosomal interorganelle tethering protein. J Cell Biol 210, 541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan PG, Lewis RS & Rao A (2010). Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu Rev Immunol 28, 491–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M, Fanger CM & Lewis RS (1997). Mitochondrial regulation of store‐operated calcium signaling in T lymphocytes. J Cell Biol 137, 633–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M & Penner R (1992). Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature 355, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idevall‐Hagren O, Lu A, Xie B & De Camilli P (2015). Triggered Ca2+ influx is required for extended synaptotagmin 1‐induced ER‐plasma membrane tethering. EMBO J 34, 2291–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar P & Parekh AB (2015). Distinct spatial Ca2+ signatures selectively activate different NFAT transcription factor isoforms. Mol Cell 58, 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar P, Samanta K, Kramer H, Morris O, Bakowski D & Parekh AB (2014). Dynamic assembly of a membrane signaling complex enables selective activation of NFAT by Orai1. Curr Biol 24, 1361–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick BS, Eden ER, Schapira AH, Futter CE & Patel S (2013). Direct mobilisation of lysosomal Ca2+ triggers complex Ca2+ signals. J Cell Sci 126, 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Guzman‐Hernandez ML, Wisniewski E & Balla T (2015). Phosphatidylinositol‐phosphatidic acid exchange by Nir2 at ER‐PM contact sites maintains phosphoinositide signaling competence. Dev Cell 33, 549–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Stotz SC, Manasian Y & Clapham DE (2011). POST, partner of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), targets STIM1 to multiple transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 19234–19239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KP, Yuan JP, Hong JH, So I, Worley PF & Muallem S (2010. a). An endoplasmic reticulum/plasma membrane junction: STIM1/Orai1/TRPCs. FEBS Lett 584, 2022–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KP, Yuan JP, So I, Worley PF & Muallem S (2010. b). STIM1‐dependent and STIM1‐independent function of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels tunes their store‐operated mode. J Biol Chem 285, 38666–38673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkimmiatis K, Srikanthan M, Maiellaro I, Moyer MP, Curci S & Hofer AM (2009). Store‐operated cyclic AMP signalling mediated by STIM1. Nat Cell Biol 11, 433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Fivaz M, Inoue T & Meyer T (2007). Live‐cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 9301–9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE Jr & Meyer T (2005). STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+‐store‐depletion‐triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 15, 1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CJ, Young BP, Tavassoli S & Levine TP (2007). Inheritance of cortical ER in yeast is required for normal septin organization. J Cell Biol 179, 467–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik RM, Wu MM, Buchanan J & Lewis RS (2006). The elementary unit of store‐operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER‐plasma membrane junctions. J Cell Biol 174, 815–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lur G, Haynes LP, Prior IA, Gerasimenko OV, Feske S, Petersen OH, Burgoyne RD & Tepikin AV (2009). Ribosome‐free terminals of rough ER allow formation of STIM1 puncta and segregation of STIM1 from IP3 receptors. Curr Biol 19, 1648–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiellaro I, Lefkimmiatis K, Moyer MP, Curci S & Hofer AM (2012). Termination and activation of store‐operated cyclic AMP production. J Cell Mol Med 16, 2715–2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleth J, Choi S, Muallem S & Ahuja M (2014). Translocation between PI(4,5)P2‐poor and PI(4,5)P2‐rich microdomains during store depletion determines STIM1 conformation and Orai1 gating. Nat Commun 5, 5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manford AG, Stefan CJ, Yuan HL, Macgurn JA & Emr SD (2012). ER‐to‐plasma membrane tethering proteins regulate cell signaling and ER morphology. Dev Cell 23, 1129–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjarres IM, Alonso MT & Garcia‐Sancho J (2011). Calcium entry‐calcium refilling (CECR) coupling between store‐operated Ca2+ entry and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase. Cell Calcium 49, 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjarres IM, Rodriguez‐Garcia A, Alonso MT & Garcia‐Sancho J (2010). The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) is the third element in capacitative calcium entry. Cell Calcium 47, 412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogami H, Tepikin AV & Petersen OH (1998). Termination of cytosolic Ca2+ signals: Ca2+ reuptake into intracellular stores is regulated by the free Ca2+ concentration in the store lumen. EMBO J 17, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser von Filseck J, Copic A, Delfosse V, Vanni S, Jackson CL, Bourguet W & Drin G (2015). Phosphatidylserine transport by ORP/Osh proteins is driven by phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate. Science 349, 432–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes P, Cornut D, Bochet V, Hasler U, Oh‐Hora M, Waldburger JM & Demaurex N (2012). STIM1 juxtaposes ER to phagosomes, generating Ca2+ hotspots that boost phagocytosis. Curr Biol 22, 1990–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeke E, Parker T, Dingsdale H, Concannon M, Awais M, Voronina SG, Molgo J, Begg M, Metcalf D, Knight AE, Sutton R, Haynes LP & Tepikin AV (2016). Epithelial‐ mesenchymal transition, IP3 receptors and ER‐PM junctions: translocation of Ca2+ signalling complexes and regulation of migration. Biochem J 473, 757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong HL & Ambudkar IS (2015). Molecular determinants of TRPC1 regulation within ER‐PM junctions. Cell Calcium 58, 376–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L, Ravazzola M, Le Coadic M, Shen WW, Demaurex N & Cosson P (2009). STIM1‐induced precortical and cortical subdomains of the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 19358–19362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB & Putney JW Jr (2005). Store‐operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev 85, 757–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CY, Hoover PJ, Mullins FM, Bachhawat P, Covington ED, Raunser S, Walz T, Garcia KC, Dolmetsch RE & Lewis RS (2009). STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell 136, 876–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MK, Ashby MC, Erdemli G, Petersen OH & Tepikin AV (2001). Perinuclear, perigranular and sub‐plasmalemmal mitochondria have distinct functions in the regulation of cellular calcium transport. EMBO J 20, 1863–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MK, Petersen OH & Tepikin AV (2000). The endoplasmic reticulum as one continuous Ca2+ pool: visualization of rapid Ca2+ movements and equilibration. EMBO J 19, 5729–5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins GA, Tjong J, Brown JM, Poquiz PH, Scott RT, Kolson DR, Ellisman MH & Spirou GA (2010). The micro‐architecture of mitochondria at active zones: electron tomography reveals novel anchoring scaffolds and cristae structured for high‐rate metabolism. J Neurosci 30, 1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OH & Tepikin AV (2008). Polarized calcium signaling in exocrine gland cells. Annu Rev Physiol 70, 273–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter KR & Palade GE (1957). Studies on the endoplasmic reticulum. III. Its form and distribution in striated muscle cells. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 3, 269–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Rao A & Hogan PG (2006). Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature 443, 230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz WA (2014). Bridging the gap: membrane contact sites in signaling, metabolism, and organelle dynamics. J Cell Biol 205, 759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW Jr (2007). Recent breakthroughs in the molecular mechanism of capacitative calcium entry (with thoughts on how we got here). Cell Calcium 42, 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie MF, Samakai E & Soboloff J (2012). STIM1 is required for attenuation of PMCA‐mediated Ca2+ clearance during T‐cell activation. EMBO J 31, 1123–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA & Pozzan T (1998). Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science 280, 1763–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romsicki Y, Reece M, Gauthier JY, Asante‐Appiah E & Kennedy BP (2004). Protein tyrosine phosphatase‐1B dephosphorylation of the insulin receptor occurs in a perinuclear endosome compartment in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. J Biol Chem 279, 12868–12875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G & Stauderman KA (2005). STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store‐operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169, 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth PR, Arias B, Quartetti EV & Carney AL (1962). Current management of subdural hematoma. Analysis of 100 consecutive cases. JAMA 179, 759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta K, Douglas S & Parekh AB (2014). Mitochondrial calcium uniporter MCU supports cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations, store‐operated Ca2+ entry and Ca2+‐dependent gene expression in response to receptor stimulation. PloS One 9, e101188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz TA, Choi MG, Raychaudhuri S, Mears JA, Ghirlando R, Hinshaw JE & Prinz WA (2009). Lipid‐regulated sterol transfer between closely apposed membranes by oxysterol‐binding protein homologues. J Cell Biol 187, 889–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Quintana A, Findlay GM, Mettlen M, Baust B, Jain M, Nilsson R, Rao A & Hogan PG (2013). An siRNA screen for NFAT activation identifies septins as coordinators of store‐operated Ca2+ entry. Nature 499, 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ & Feske S (2012). Physiological and pathophysiological functions of SOCE in the immune system. Frontiers Biosci 4, 2253–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan CJ, Manford AG, Baird D, Yamada‐Hanff J, Mao Y & Emr SD (2011). Osh proteins regulate phosphoinositide metabolism at ER‐plasma membrane contact sites. Cell 144, 389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima H, Hoshijima M & Song LS (2015). Ca2+ microdomains organized by junctophilins. Cell Calcium 58, 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepikin AV, Voronina SG, Gallacher DV & Petersen OH (1992). Pulsatile Ca2+ extrusion from single pancreatic acinar cells during receptor‐activated cytosolic Ca2+ spiking. J Biol Chem 267, 14073–14076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G, Tepikin AV, Tengholm A & Gylfe E (2012). cAMP induces stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) puncta but neither Orai1 protein clustering nor store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) in islet cells. J Biol Chem 287, 9862–9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FC & Meyer T (2012). Ca2+ pulses control local cycles of lamellipodia retraction and adhesion along the front of migrating cells. Curr Biol 22, 837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FC, Seki A, Yang HW, Hayer A, Carrasco S, Malmersjo S & Meyer T (2014). A polarized Ca2+, diacylglycerol and STIM1 signalling system regulates directed cell migration. Nat Cell Biol 16, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi A, Cirulli V & Rutter GA (2004). Mitochondrial localization as a determinant of capacitative Ca2+ entry in HeLa cells. Cell Calcium 36, 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai P, Toth B, Toth DJ, Hunyady L & Balla T (2007). Visualization and manipulation of plasma membrane‐endoplasmic reticulum contact sites indicates the presence of additional molecular components within the STIM1‐Orai1 complex. J Biol Chem 282, 29678–29690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan‐Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R & Kinet JP (2006). CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store‐operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312, 1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina S, Collier D, Chvanov M, Middlehurst B, Beckett AJ, Prior IA, Criddle DN, Begg M, Mikoshiba K, Sutton R & Tepikin AV (2015). The role of Ca2+ influx in endocytic vacuole formation in pancreatic acinar cells. Biochem J 465, 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CM, Chvanov M, Haynes LP, Petersen OH, Tepikin AV & Burgoyne RD (2010). Role of phosphoinositides in STIM1 dynamics and store‐operated calcium entry. Biochem J 425, 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Groenendyk J & Michalak M (2015). Glycoprotein quality control and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecules 20, 13689–13704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Wang X, Chen M, Ouyang K, Song LS & Cheng H (2009). Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature 457, 901–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L, Voronina S, Javed MA, Awais M, Szatmary P, Latawiec D, Chvanov M, Collier D, Huang W, Barrett J, Begg M, Stauderman K, Roos J, Grigoryev S, Ramos S, Rogers E, Whitten J, Velicelebi G, Dunn M, Tepikin AV, Criddle DN & Sutton R (2015). Inhibitors of ORAI1 prevent cytosolic calcium‐associated injury of human pancreatic acinar cells and acute pancreatitis in 3 mouse models. Gastroenterology 149, 481–492 e487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby D, Everett KL, Halls ML, Pacheco J, Skroblin P, Vaca L, Klussmann E & Cooper DM (2012). Direct binding between Orai1 and AC8 mediates dynamic interplay between Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Sci Signal 5, ra29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby D, Wachten S, Masada N & Cooper DM (2010). Direct demonstration of discrete Ca2+ microdomains associated with different isoforms of adenylyl cyclase. J Cell Sci 123, 107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM & Lewis RS (2006). Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol 174, 803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MM, Covington ED & Lewis RS (2014). Single‐molecule analysis of diffusion and trapping of STIM1 and Orai1 at endoplasmic reticulum‐plasma membrane junctions. Mol Biol Cell 25, 3672–3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JP, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Choi YJ, Worley PF & Muallem S (2009). SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat Cell Biol 11, 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach A & Lewis RS (1993). Mitogen‐regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90, 6295–6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]