Abstract

Key points

The presence of insulin resistance (IR) is determinant for endothelial dysfunction associated with obesity.

Although recent studies have implicated the involvement of mitochondrial superoxide and inflammation in the defective nitric oxide (NO)‐mediated responses and subsequent endothelial dysfunction in IR, other mechanisms could compromise this pathway.

In the present study, we assessed the role of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and arginase with respect to IR‐induced impairment of endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation in human morbid obesity and in a non‐obese rat model of IR.

We show that both increased ADMA and up‐regulated arginase are determinant factors in the alteration of the l‐arginine/NO pathway associated with IR in both models and also that acute treatment of arteries with arginase inhibitor or with l‐arginine significantly alleviate endothelial dysfunction.

These results help to expand our knowledge regarding the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction that are related to obesity and IR and establish potential therapeutic targets for intervention.

Abstract

Insulin resistance (IR) is determinant for endothelial dysfunction in human obesity. Although we have previously reported the involvement of mitochondrial superoxide and inflammation, other mechanisms could compromise NO‐mediated responses in IR. We evaluated the role of the endogenous NOS inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and arginase with respect to IR‐induced impairment of l‐arginine/NO‐mediated vasodilatation in human morbid obesity and in a non‐obese rat model of IR. Bradykinin‐induced vasodilatation was evaluated in microarteries derived from insulin‐resistant morbidly obese (IR‐MO) and non‐insulin‐resistant MO (NIR‐MO) subjects. Defective endothelial vasodilatation in IR‐MO was improved by l‐arginine supplementation. Increased levels of ADMA were detected in serum and adipose tissue from IR‐MO. Serum ADMA positively correlated with IR score and negatively with pD2 for bradykinin. Gene expression determination by RT‐PCR revealed not only the decreased expression of ADMA degrading enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH)1/2 in IR‐MO microarteries, but also increased expression of arginase‐2. Arginase inhibition improved endothelial vasodilatation in IR‐MO. Analysis of endothelial vasodilatation in a non‐obese IR model (fructose‐fed rat) confirmed an elevation of circulating and aortic ADMA concentrations, as well as reduced DDAH aortic content and increased aortic arginase activity in IR. Improvement of endothelial vasodilatation in IR rats by l‐arginine supplementation and arginase inhibition provided functional corroboration. These results demonstrate that increased ADMA and up‐regulated arginase contribute to endothelial dysfunction as determined by the presence of IR in human obesity, most probably by compromising arginine availability. The results provide novel insights regarding the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction related to obesity and IR and establish potential therapeutic targets for intervention.

Key points

The presence of insulin resistance (IR) is determinant for endothelial dysfunction associated with obesity.

Although recent studies have implicated the involvement of mitochondrial superoxide and inflammation in the defective nitric oxide (NO)‐mediated responses and subsequent endothelial dysfunction in IR, other mechanisms could compromise this pathway.

In the present study, we assessed the role of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and arginase with respect to IR‐induced impairment of endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation in human morbid obesity and in a non‐obese rat model of IR.

We show that both increased ADMA and up‐regulated arginase are determinant factors in the alteration of the l‐arginine/NO pathway associated with IR in both models and also that acute treatment of arteries with arginase inhibitor or with l‐arginine significantly alleviate endothelial dysfunction.

These results help to expand our knowledge regarding the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction that are related to obesity and IR and establish potential therapeutic targets for intervention.

Abbreviations

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethylarginine

- CR

control rat

- CRP

C‐reactive protein

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DDAH

dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase

- eNOS

endothelial NO synthase

- HOMA‐IR

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- IR

insulin resistance

- IRR

insulin‐resistant rat

- MO

morbidly obese

- NIR

non‐insulin‐resistant

- nor‐NOHA

N ω–hydroxyl‐nor‐l‐arginine

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

Introduction

Obesity, one of the major public health problems, is an important risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Burke et al. 2008). Insulin resistance (IR) has been proposed as the link between obesity and CVD (Reaven, 2011). Indeed, we have recently revealed the determinant role of IR in the presence of endothelial dysfunction, as manifested by impaired endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation, in morbidly obese (MO) individuals (El Assar et al. 2013).

IR is a pathological situation that, in addition to predicting type 2 diabetes, represents an important risk factor for CVD (Reaven, 2012). This is probably related to the impact of IR on endothelial vasodilatation because a defective response has been detected in different vascular beds in humans with this condition (Suzuki et al. 2007; Fujii et al. 2008). Furthermore, in animal models, the induction of IR by feeding rats with high levels of fructose results in impaired endothelium‐dependent relaxation in both macro‐ and microvessels (Katakam et al. 1999; El Assar et al. 2015 c), providing a well‐characterized model of endothelial dysfunction.

We have previously shown that, among the potential mechanisms explaining the endothelial dysfunction determined by the presence of IR in morbid obesity, the impairment of nitric oxide (NO)‐mediated vasodilatation is highly relevant. We have demonstrated the involvement of both mitochondria‐generated superoxide anion and inflammation in the defective NO‐mediated responses associated with the insulin‐resistant condition (El Assar et al. 2013; El Assar et al. 2015 a). However, it is noteworthy that, in addition to the above mentioned mechanisms, other mechanisms may compromise NO‐responses and therefore remain to be explored.

The endothelium‐derived NO is produced from the substrate l‐arginine by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS). Even though l‐arginine is the main precursor of NO, the regulation of NO production is multifactorial and is not limited by circulating l‐arginine but, instead, by intracellular substrate and co‐factor availability, NOS activation, and NOS inhibition by endogenous analogues of l‐arginine, such as asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) (Vallance et al. 1992). An increase in ADMA could lead to impaired NO bioavailability and vascular dysfunction (Anderssohn et al. 2010). In line with this, evidence has been obtained showing increased ADMA levels in different clinical settings associated with the appearance and progression of vascular disease, such as in essential hypertension, diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance (IR) (Stuhlinger et al. 2002; Das et al. 2011). Moreover, the endogenous production of ADMA has been proposed as an explanation for the ‘l‐arginine paradox’. Indeed, exogenous supplementation of l‐arginine was observed to increase NO production both in vivo and in vitro. This occurs despite the presence of a baseline concentration of l‐arginine sufficient to saturate NOS (Boger, 2004). Therefore, the presence of an endogenous competitive antagonist, such as ADMA, at the active site of the enzyme might provide a satisfactory explanation for this phenomenon (Caplin & Leiper, 2012).

The vast majority of ADMA is removed by enzymatic degradation by dimethylarginine‐dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH). The two DDAH isoforms, DDAH1 and DDAH2, share similar enzymatic activity but have distinct vascular distributions (Leiper et al. 1999). Nonetheless, heterozygous deletion studies suggest that DDAH1 is the primary isoform responsible for ADMA degradation in the vascular endothelium and it appears to play a role in endothelial function in vivo (Hu et al. 2009). A recent study showed that insulin‐resistant rats (IRRs) exhibit not only a reduction in DDAH activity and aortic expression of DDAH1, but also an increase in plasma ADMA levels (Chen et al. 2012). Accordingly, elevated circulating ADMA concentrations were shown to be associated with IR in patients under different conditions (Perticone et al. 2010), including obesity (Marliss et al. 2006). However, the relationship between ADMA and endothelial function in subjects with IR is not completely established. An inverse association between forearm blood flow and serum ADMA levels has been reported in both hypertensive subjects and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients (Perticone et al. 2005; Sciacqua et al. 2012), whereas no significant correlation between ADMA and NO production has been detected in other studies (Kocak et al. 2011; Siervo & Bluck, 2012). Furthermore, the improvement of endothelial function after weight loss in obese subjects appears to be independent of ADMA reduction (Rudofsky et al. 2011).

By contrast, a reduced availability of l‐arginine for NO synthesis is determined, among other factors, by the activity of alternative pathways of l‐arginine metabolism, such as the action of arginases. Arginase, including type 1 and type 2 isoforms, competes directly with eNOS for l‐arginine. Both arginase isoforms are expressed in endothelial cells and display similar roles with respect to the negative regulation of eNOS function (Yang & Ming, 2013). Therefore, an increase in arginase activity can decrease the tissue/cellular content of l‐arginine available to eNOS, thus limiting NO production (Durante et al. 2007). In this sense, sustained arginase inhibition ameliorates hypertension in fructose‐fed rats via its direct effect on endothelium‐dependent relaxation and NO generation (El‐Bassossy et al. 2013). Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate that genetic ablation of arginase‐2 in mice fed a high‐fat diet reduces atherosclerosis and improve insulin sensitivity (Ming et al. 2012), and also preserves the endothelium‐dependent relaxation of the aorta (Yu et al. 2014).

The present study aimed to test the hypothesis that IR results in elevated ADMA concentrations and/or increased arginase activity/expression. Both alterations will compromise the l‐arginine/NO pathway, subsequently leading to impaired endothelial vasodilatation. We assessed this hypothesis in human obese subjects with or without IR in a non‐obese rat model of IR by determining the presence of ADMA/arginase enhancement by IR, as well as by evaluating the effects of arginine supplementation and arginase inhibition on endothelial vasodilatation in arteries from humans and rats with IR.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study conducted in humans was approved by both the Ethics Committee and Research Committee of the Hospital Universitario de Getafe. Studies conducted in animals were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as adopted and promulgated by National Institutes of Health, and were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of the Hospital Universitario de Getafe

Study population

The present study included 41 MO subjects with a body mass index ≥40 kg m–2 and aged between 26 and 65 years, who underwent bariatric surgery in the Hospital Universitario de Getafe with mixed techniques combining Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass, vertical sleeve gastrectomy and adjustable gastric banding. Subjects with history or clinical evidence of CVD (congestive heart failure; cardiac and/or cerebrovascular ischaemic disease) were excluded, although this did not include those with cardiovascular risk factors such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia or smoking. In addition, subjects with pre‐existing kidney and liver failure, pregnancy, use of corticosteroids from 4 weeks before surgery, coeliac or Crohn's disease, or another major cause of intestinal malabsorption and malnourishment, were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in the study.

IR was estimated by calculating the validated index for homeostasis model assessment of IR (HOMA‐IR) (Wallace et al. 2004). MO subjects were distributed into two groups according to the HOMA‐IR score: non‐insulin‐resistant (NIR) (HOMA‐IR < 3.8; n = 14) and insulin‐resistant (IR) (HOMA‐IR ≥ 3.8; n = 27). The cut‐off point was previously defined for a Spanish population corresponding to the 90th percentile HOMA‐IR value in non‐diabetic adult subjects (Ascaso et al. 2001).

Blood samples were obtained by venipuncture from overnight fasting patients and collected in tubes free of anti‐coagulant for serum isolation or with EDTA as an anti‐coagulant for plasma extraction. Plasma and serum were obtained by centrifugation and then stored at −80ºC until determinations were made.

Animal model for IR

To support the results obtained in human beings and to confirm that they are determined by the presence of IR but not any other potential mechanisms existing in individuals with morbid obesity, we evaluated comparable determinations in a model of IR in absence of obesity: the fructose‐fed rat.

A total of twenty male Sprague–Dawley rats from Harlan Laboratories (Barcelona, Spain) were used. Rats were kept in a room under 12:12 h light/dark cycles and with free access to chow and water. Fructose‐fed rats were used as a well‐characterized model of IRRs that has been validated previously (El Assar et al. 2015 b; El Assar et al. 2015 c). Four‐ to 5‐week‐old rats were fed with fructose (20% w/v) in drinking water for 8 weeks. At that time, the rats developed endothelial dysfunction, as manifested by an impaired ACh‐induced relaxation, as well as IR as confirmed by the significant increase in the HOMA index compared to age‐matched rats (El Assar et al. 2015 b; El Assar et al. 2015 c). Age‐matched rats maintained under the same conditions but not receiving fructose in drinking water were used as control rats (CR).

Overnight‐fasted rats were weighed and anaesthetized with diazepam (5 mg kg−1) and ketamine (90 mg kg−1). Blood samples were obtained via cardiac puncture and collected in anti‐coagulant‐free tubes and in EDTA‐tubes for sera or plasma extraction for biochemical measurements. Sera and plasma were obtained by centrifugation and stored at −80ºC until determinations were made. Immediately after blood collection, the mesenteric fat pad was removed in block for isolation of mesenteric microvessels and the thoracic aorta was carefully excised.

Biochemical measurements

Blood samples were collected from MO subjects for measurement of serum fasting glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C), serum fasting insulin, serum lipid profile and C‐reactive protein (CRP) in accordance with the routine procedures of the Laboratory of Clinical Analyses of our hospital. HOMA‐IR was calculated as described by Matthews et al. (1985). Circulating levels of insulin were determined in the serum of overnight fasting rats by an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Serum glucose concentrations were determined using a colorimetric commercial kit (Biolabo SA, Maizy, France). HOMA‐IR, calculated as described above, was normalized to the value obtained in CR. All samples were assessed in duplicate.

Evaluation of vascular relaxation in isolated human microarteries

Small arteries (200–500 μm, ∼2 mm in length) were isolated from visceral fat obtained from MO subjects during laparoscopic surgery and placed in a Petri dish containing Krebs–Henseleit solution (KHS; composition in mm: 115 NaCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 4.6 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4.7H2O, 25 NaHCO3, 11.1 glucose and 0.03 Na2EDTA). The arteries were cleaned, and mounted as ring preparations on small vessel wire myographs containing KHS at 37ºC continuously aerated with 95% O2–5% CO2 mixture, which gave a pH of 7.4, as described previously (Rodriguez‐Mañas et al. 2009; El Assar et al. 2013). Briefly, resting tension was calculated to obtain an internal circumference equivalent to 90% of the tension of the vessels when relaxed in situ under a transmural pressure of 100 mmHg, using Myo‐Norm‐4 (Cibertec, Madrid, Spain). Tension was continuously recorded via a data acquisition system (MP100A BIOPAC System; Biopac, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). To test for viability, arteries were allowed to stabilize for 30 min and then exposed to 125 mm K+ (KKHS; equimolar substitution of KCl for NaCl in KHS). The segments failing to produce a tension equivalent to a pressure of 100 mmHg were rejected. After a washout period, the arteries were contracted again with 25 mm K+, which produced ∼80% of the maximum response. When the contraction reached a plateau, endothelium‐dependent relaxation was assessed by adding increasing concentrations of bradykinin (BK) (10 nm to 3 μm) to the organ bath. Responses to sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 1 nm to 100 μm) were used to test non‐endothelium‐dependent relaxation.

Determination of endothelium‐dependent vasodilator responses in macro‐ and microvessels of rats

Small mesenteric arteries (200–500 μm, ∼2 mm in length) and thoracic aorta rings (4–5 mm in length) were set up in wire myographs and organ baths, respectively, containing KHS at 37ºC bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 mixture, in accordance with methods described previously (Rodríguez‐Mañas et al. 2003; Angulo et al. 1996). Tension was continuously recorded via a data acquisition system (MP100A BIOPAC System). For studying the vasodilator response of the mesenteric arteries and aorta, rings were first precontracted with norepinephrine (1–3 μm and 10–30 nm for mesenteric arteries and aorta, respectively). When a stable plateau was reached, increasing concentrations of ACh (final bath concentrations: 1 nm to 10 μm for mesenteric arteries; 10 nm to 10 μm for aorta) were added to the organ chamber and vasodilatory responses were determined. Responses to SNP (1 nm to 100 μm) were used to test‐non‐endothelium‐dependent relaxation.

Evaluation of the effect of l‐arginine and arginase inhibition on vascular responses

To test the possible involvement of a diminished concentration/availability of NOS substrate with respect to the endothelial dysfunction related to IR in both experimental approaches, arterial segments were pretreated 30 min before BK or ACh administration with l‐arginine (300 μm). In another series of experiments, the contribution of arginase to the defective relaxation associated with IR was determined by incubating vascular segments with the arginase inhibitor, N ω–hydroxyl‐nor‐l‐arginine (nor‐NOHA) (10 μm) for 30 min.

The experiments were systematically performed in parallel for each series of experiments and the treatments with l‐arginine or arginase inhibitor were randomly assigned to different segments from the same donor.

Determination of arginine, ADMA and DDAH1 content

Arginine was determined in plasma, whereas ADMA levels were measured in sera and visceral adipose tissue extract derived from human MO subjects. Levels of ADMA and arginine were determined in serum or plasma respectively, as well as in aortic homogenates of rats. The DDAH1 concentration was evaluated in the aortic tissue of animals. The measured concentrations of ADMA, arginine and DDAH1 evaluated in tissues (visceral adipose tissue or aortic rings) were normalized to the protein content (mg) of each visceral adipose tissue or aortic ring. All determinations, both in sera and tissue samples, were performed using the respective colorimetric ELISA kits (USCN Life Science Inc., Houston, TX, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. For each determination, samples were assessed in duplicate.

Determination of aortic arginase activity

Arginase activity in the aortic tissue lysate was measured by colorimetric determinations of an intermediate product formed from the arginase reaction with arginine in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions of a commercially available kit (# ab180877; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). All tissue samples were assessed in duplicate and measured at 570 nm in kinetic mode for 30 min at 37ºC using a GENios Plus instrument (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). The measured activities were normalized to protein content (mg) of each aortic ring.

Real‐time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from human visceral arteries with RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valancia, CA, USA). The concentration and purity of RNA recovery were determined by spectrophotometry (ND‐100 spectrophotometer; Nanodrop Technology, Montchanin, DE, USA). First‐strand cDNA was synthesized from 250 ng of RNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. In total, 25 ng of cDNA was amplified by using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix and TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) with inventoried probes for eNOS (Hs00167166_m1), DDAH1 (Hs00201707_m1), DDAH2 (Hs00203889_m1), arginase‐2 (Hs00982833_m1) and human GAPDH (4326317). PCR reactions (12 μl) were performed in duplicate on the 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Life Technologies) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH (used as a reference gene). Relative expression levels were determined using the comparative Ct method [2−ddCt].

Chemicals

All drugs used were purchased from Sigma (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), except for nor‐NOHA, which was obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Drug solutions were made in distilled water, except norepinephrine, which was prepared in saline (0.9% NaCl) containing ascorbic acid (0.01% w/v) to avoid oxidation.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analysed by the chi‐squared test. Results from numerical variables are expressed as the mean ± SE. The number of subjects/animals (N) or the number of vascular segments (n) used for relaxation curves is indicated as appropriate. Complete concentration–response curves to BK or to ACh in vessels from the participants and animals, respectively, were compared by two‐way ANOVA. pD2 (which is defined as the negative logarithm of the concentration of vasodilator required to obtain 50% of maximal relaxation) and the numerical variables for each subject/animal were compared using an unpaired Student's t test. Models of linear regression were constructed, with the pD2 considered as the dependent variable. In all cases, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Humans

Impaired endothelial vasodilatation related to IR in human morbid obesity: improvement by l‐arginine

Insulin‐resistant morbidly obese (IR‐MO) subjects showed higher concentrations of fasting glucose, insulin and CRP, as well as notably elevated HOMA‐IR, whereas total cholesterol, high and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were lower compared to the non‐insulin‐resistant morbidly obese (NIR‐MO) group (Table 1). Comorbid conditions and the treatments received by the patients at the time of surgery are also shown in Table 1. As expected, the proportion of diabetes mellitus was significantly higher in IR‐MO subjects.

Table 1.

Basal variables of morbidly obese subjects

| Characteristic | NIR (N = 14) | IR (N = 27) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | |||

| Age (years) | 45.6 ± 3.8 | 41.7 ± 1.9 | 0.376 |

| Sex (male/female) | 1 /13 | 13/14 | 0.014 |

| Body mass index (kg m–2) | 45.0 ± 0.9 | 47.0 ± 1.1 | 0.215 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 (%) | 0.0 | 48.1 | <0.01 |

| Hypertension (%) | 21.4 | 51.9 | 0.061 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 14.3 | 25.9 | 0.393 |

| Active smokers (%) | 7.1 | 22.2 | 0.224 |

| Chemical | |||

| Fasting glucose (mg dl–1) | 88.4 ± 2.0 | 103.9 ± 2.7 | <0.01 |

| HbA1C % (mmol mol–1) | 5.6 (35.18 ± 2.3) | 6.0 (40.44 ± 2.0) | 0.073 |

| Total cholesterol (mg dl–1) | 184.2 ± 9.6 | 153.9 ± 6.3 | 0.010 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg dl–1) | 47.7 ± 2.5 | 38.5 ± 1.8 | <0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg dl–1) | 110.8 ± 8.2 | 87.2 ± 5.9 | 0.024 |

| Ratio (TC/HDL) | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 0.644 |

| Triglycerides (mg dl–1) | 100.6 ± 8.4 | 127.3 ± 9.6 | 0.076 |

| Fasting insulin (μU ml–1) | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 32.9 ± 4.0 | <0.001 |

| HOMA‐IR | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg l–1) | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 10.9 ± 1.4 | <0.01 |

| Treatment | |||

| Hypoglycaemic drugs (%) | 0.0 | 48.1 | <0.01 |

| Hypotensive drugs (%) | 14.3 | 51.9 | 0.041 |

| Lipid‐lowering drugs (%) | 0.0 | 18.5 | 0.097 |

HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; TC, total cholesterol. Significant differences are highlighted in bold.

Small mesenteric arteries derived from IR‐MO subjects showed a clear reduction in the endothelium‐mediated vasodilatation induced by BK compared to the NIR‐MO group (Fig. 1 A). To avoid a possible potential bias as a result of a comparison of the vascular segment‐derived responses instead of comparing the response in subjects, we assessed the differences between the pD2 values for BK averaged from all vascular segments from each subject by group (NIR‐MO and IR‐MO).This approach yielded results very similar to those observed when we analysed the response of the vessels (pD2 values: 7.40 ± 0.14 vs. 6.45 ± 0.19 for NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects, respectively; P = 0.001). Furthermore, the vasorelaxant response to BK in microarteries derived from MO subjects decreased as the HOMA‐IR index increased, with a clear correlation between the HOMA‐IR index and the BK pD2 values (r = 0.397; P = 0.01). Furthermore, among all factors studied, only HOMA‐IR was associated with BK pD2 values.

Figure 1. Effect of l‐arginine on endothelial dysfunction associated with IR in morbidly obese subjects .

Relaxation to BK in mesenteric arterial segments derived from NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects (A) and effects of preincubation with l‐arginine (l‐arg) (300 μm) in arteries from NIR‐MO (C) and IR‐MO subjects (D). Data are expressed as the percentage of the contraction elicited by K+. ***P < 0.001 vs. NIR‐MO; **P < 0.01 vs. IR‐MO subjects. B, plasmatic concentrations of arginine in NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects.

Comparable differences in endothelial vasodilatation between NIR‐MO and IR‐MO groups were observed after excluding males from both groups (pD2 for BK after excluding male subjects: 7.42 ± 0.15 vs. 6.60 ± 0.26, P = 0.014), and after excluding diabetic patients from IR‐MO group (pD2 values were 7.40 ± 0.14 vs. 6.50 ± 0.24 for NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects, respectively; P = 0.002). No statistically significant differences were found in the non‐endothelium‐dependent vasodilatations induced by SNP in microarteries from IR‐MO subjects compared to NIR‐MO subjects (pD2 4.95 ± 0.25 vs. 5.10 ± 0.30 for NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects, respectively; not significant).

A diminished concentration/availability of nitric oxide precursor, l‐arginine, was tested as a possible mechanism underlying the altered vascular relaxation associated with the presence of IR status. Although plasma concentrations of arginine did not differ between insulin‐resistant and insulin‐sensitive MO subjects (Fig. 1 B), incubating vascular segments with l‐arginine (300 μm) resulted in a marked improvement in endothelial vasodilatation in IR‐MO subjects (Fig. 1 D), whereas it had no effect on microarteries derived from the NIR‐MO group (Fig. 1 C).

The presence of IR is associated with increased concentrations of systemic and tissue ADMA in morbidly obese subjects

Serum (Fig. 2 A) and visceral adipose tissue extract (Fig. 2 B) levels of ADMA derived from MO subjects were significantly increased in those who were insulin‐resistant compared to NIR‐MO subjects (P < 0.05). Furthermore, mRNA expression of both isoforms of the key enzyme of ADMA catabolism (DDAH‐1 and DDAH‐2) was significantly diminished in human microvessels in the IR condition, whereas no significant differences were detected in eNOS expression between IR‐MO and NIR‐MO subjects (Fig. 2 C)

Figure 2. Insulin resistance is associated with increased levels of ADMA in morbidly obese subjects .

ADMA values determined in sera (A) and in adipose tissue surrounding microarteries (B) from NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects. C, mRNA relative expression of eNOS, DDAH‐1 and DDAH‐2 in mesenteric arteries derived form NIR‐MO and IR‐MO. Mesenteric arteries for gene expression analysis were obtained, from four to eight different patients. *P < 0.05 vs. NIR‐MO subjects. D, positive correlation between ADMA concentrations and HOMA‐IR score. E, negative correlation between ADMA and pD2 values for BK. Each point represents the averaged pD2 values of segments from one single subject.

In addition, serum ADMA concentrations were positively correlated with HOMA‐IR score and inversely correlated with endothelial vasodilatation capacity measured as BK pD2 values (Fig. 2 D and E).

Arginase contributes to endothelial dysfunction associated with IR in human morbid obesity

Arginase, a l‐arginine catabolizing enzyme, has been postulated as a possible mechanism contributing to endothelial dysfunction. Accordingly, the mRNA expression of arginase‐2 was determined in mesenteric microvessels derived from obese subjects. An up‐regulation of arginase‐2 gene expression was detected in mesenteric microvessels from IR‐MO subjects compared to the NIR‐MO group (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3. Arginase contributes to the endothelial dysfunction related to IR in morbidly obese patients .

A, arginase‐2 (Arg‐2) mRNA relative expression in isolated mesenteric arteries form NIR‐MO and IR‐MO subjects. *P < 0.05 vs. NIR‐MO subjects. Mesenteric arteries were obtained from four to five different patients. The effect of preincubation with arginase inhibitor, nor‐NOHA (10 μm), on relaxation to BK in mesenteric arterial segments derived form NIR‐MO (C) and IR‐MO (B) subjects is shown. Data are expressed as the percentage of contraction elicited by K+. **P < 0.01 vs. IR‐MO subjects.

Arginase can decrease NO production by competing with NOS for arginine as a substrate. To determine the contribution of arginase to defective relaxation associated with IR, vascular segments were incubated with the arginase inhibitor, nor‐NOHA (10 μm). Arginase inhibition caused a significant improvement of endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation in microarteries derived from IR‐MO subjects (Fig. 3 B). By contrast, nor‐NOHA did not modify endothelial vasodilatation to BK in mesenteric microvessels from NIR‐MO subjects (Fig. 3 C).

Fructose‐fed rats

Endothelial malfunction in a non‐obese rat model of IR, which is alleviated by supplemental l‐arginine

The administration of d‐fructose (20%) to rats for 8 weeks resulted in significant hyperglycaemia compared to control‐matched rats (P < 0.001), as indicated in Table 2. In line with observations in IR‐MO subjects, a marked hyperinsulinaemia was also detected in IRRs because serum insulin levels were significantly elevated above the CRs (P < 0.001) (Table 2). The development of IR was confirmed by the significant increase in the HOMA‐IR score (P < 0.001) (Table 2) compared to CRs. The main difference between human and animal models was the lack of significant obesity in IRRs because these rats were only slightly and non‐significantly overweight compared to CRs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Body weight and serum concentrations of glucose and insulin for animals

| CRs (N = 8) | IRRs (N = 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 408.4 ± 20.29 | 449.8 ± 13.83 |

| Fasting glucose (mg dl–1) | 123.5 ± 11.16 | 254.6 ± 22.60*** |

| Fasting insulin (μg l–1) | 1.47 ± 0.22 | 4.59 ± 0.61*** |

| HOMA‐IR score | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 6.40 ± 0.94*** |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. N, number of rats used. ***P < 0.001 vs. control rats. Data were compared by a two‐tailed unpaired Student's t test.

Similar to that observed in humans, endothelium‐dependent vasodilatations induced by ACh (1 nm to 30 μm) in rat mesenteric arteries and aortae were significantly impaired in arteries from IRRs compared to CRs, comprising a model of endothelial dysfunction determined by IR condition rather than by obesity (Fig. 4 A and B). Meanwhile, no differences were observed in SNP‐induced vasodilatations in both mesenteric arteries and aorta derived from IRRs compared to CRs (pD2 7.02 ± 0.20 vs. 6.73 ± 0.17 for mesenteric arteries; pD2 8.17 ± 0.07 vs. 8.20 ± 0.13 for aorta from CRs and IRRs respectively; not significant).

Figure 4. Endothelial dysfunction in non‐obese fructose‐fed rats and alleviation by l‐arginine .

Relaxant responses elicited by ACh in small mesenteric arteries (A) and aortae (B) from CRs and IRRs. Acute treatment with l‐arginine (L‐arg) (300 μm) improves relaxant responses to ACh in mesenteric arteries (C) and aortae (D) from IRRs. Data are expressed as the percentage of the contraction elicited by norepinephrine (NE). ***P < 0.001 vs. CRs or vs. IRRs (in the case of l‐arginine experiments). Arginine content was also determined in plasma (E) and aortic homogenates (F) from CRs and IRRs. The samples for analysis were collected from seven to nine different animals.

Similar to observations in the human microvasculature, in this animal model displaying IR but not obesity, acute treatment with l‐arginine (300 μm) enhanced the vasodilatation induced by ACh in mesenteric arteries (Fig. 4 C) and aortae (Fig. 4 D) derived from IRRs, whereas it did not modify vasodilatation in vessels from CRs (pD2: 7.40 ± 0.14 vs. 7.16 ± 0.18; 7.32 ± 0.07 vs. 7.33 ± 0.07 for mesenteric arteries and aortae, respectively; not significant). Arginine concentrations were then evaluated for both plasmatic and aortic extracts in IRRs. Neither plasma concentrations of arginine (Fig. 4 E), nor the aortic content (Fig. 4 F) of this substrate was significantly different between CRs and IRRs.

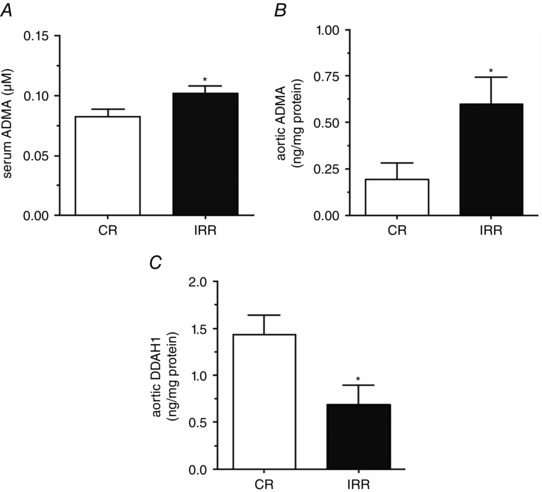

Increased systemic and vascular ADMA concentrations promote endothelial dysfunction associated with IR in rats

Systemic and vascular ADMA levels were determined in IRRs and CRs to further confirm the interaction between diminished arginine bioactivity and increased ADMA. Serum levels (Fig. 5 A) and the aortic tissue content (Fig. 5 B) of ADMA are significantly increased in fructose‐fed rats compared to control‐matched animals. Furthermore, the content of DDAH1 was significantly decreased in the aortic extract of IRRs compared to CRs (Fig. 5 C).

Figure 5. Systemic and aortic ADMA levels in fructose‐fed rats .

A, serum concentrations of ADMA in IRRs and their matched CRs. The aortic content of ADMA (B) and DDAH‐1 (C) is also shown. Samples were collected from seven different animals. *P < 0.05 vs. CR.

Increased arginase activity as a possible mechanism underpinning endothelial dysfunction associated with IR in rats

The activity of arginase was determined in the aortae extract tissue derived from CRs and from IRRs. As shown in Fig. 6 A, arginase activity was significantly increased in the aortae of IRRs compared to CRs.

Figure 6. Arginase contributes to the endothelial dysfunction observed in non‐obese fructose‐fed rats .

Arginase activity in aortic extract of CRs and IRRs is shown in (A). The aortae were extracted from seven to 10 animals for each group. The effects of the arginase inhibitor, nor‐NOHA (10 μm), on relaxation to ACh in mesenteric arteries (B) and aorta (C) of IRRs is shown. Data are expressed as the percentage of the contraction elicited by norepinephrine (NE). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. IRR.

To provide evidence related to the negative impact of arginase on endothelium‐dependent relaxation in fructose‐fed rats, vascular segments were incubated with the arginase inhibitor, nor‐NOHA (10 μm). Arginase inhibition caused a significant improvement of endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation in both mesenteric arteries and aortae derived from fructose‐fed animals (Fig. 6 B and C). By contrast, nor‐NOHA had no effect on the vasodilatation induced by ACh in arteries derived from CRs (pD2: 7.52 ± 0.14 vs. 7.51 ± 0.15 and 7.35 ± 0.07 vs. 7.37 ± 0.08, for mesenteric arteries and aortae, respectively).

Discussion

The major finding of the present study is that both an elevation of the concentrations of ADMA and an up‐regulation of arginase activity contribute to the endothelial dysfunction as a result of the presence of IR in individuals with morbid obesity. The key role for IR is additionally supported by the data obtained in non‐obese IRRs.

Obesity, an important cardiovascular risk factor, has been closely linked to IR among other metabolic derangements. This metabolic alteration, in turn, plays a pivotal role in the development of endothelial dysfunction (Prieto et al. 2014). In the present study, we confirm that MO subjects with IR demonstrated a significant decrease in endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation with respect to MO subjects who were not insulin‐resistant (El Assar et al. 2013; Lupattelli et al. 2013). In addition, and even though diabetes mellitus was only present in IR‐MO subjects, this cardiovascular risk factor does not appear to explain the negative impact of IR on endothelial function because similar defects in endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation were found after the exclusion of diabetic patients from IR‐MO compared to NIR‐MO. Similarly, the fact that the impairment of endothelial vasodilatation in IR‐MO remains after deleting data from male patients in both groups reinforces the idea that endothelial dysfunction manifested in microarteries from human obese subjects is closely related to IR condition, discarding a confusing effect of sex in the results. On the other hand, a larger percentage of IR‐MO subjects were taking hypoglycaemiants and hypotensive drugs, with the vast majority being metformin, pioglitazone and inhibitors of angiotensin‐converting enzyme. This probably did not influence the impaired endothelial dysfunction in the IR‐MO group because these agents have been reported to even improve endothelial vasodilatation (Miyamoto et al. 2012; Naka et al. 2012). Furthermore, we validated the observation obtained in humans in a well‐characterized model of IR in non‐obese fed‐fructose rats. The IR rats showed elevated fasting blood glucose and serum insulin levels, as well as a higher HOMA score. All of these alterations indicated that IR accompanied the significant decrease in endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation in these animals. The phenotype of the IRRs in the present study was consistent with that of previous studies reporting reduced endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation in fructose‐fed rats and other rat models of IR (Shinozaki et al. 1999; Young et al. 2008; El Assar et al. 2015 b).

Several possible pathophysiological mechanisms may underpin the association between IR and endothelial dysfunction. Indeed, we have reported the involvement of mitochondrial superoxide and inflammation in the impairment of NO‐mediated vasodilatation determined by the presence of IR in human morbid obesity (El Assar et al. 2013). However, other mechanisms could contribute to the defective vascular availability of NO in IR. In this sense, ADMA causes a reduction in NO synthesis by inhibiting NOS (Pope et al. 2009). Although previous studies have reported higher plasma levels of ADMA in obese patients with IR compared to NIR obese subjects (McLaughlin et al. 2006) and lower circulating concentrations of ADMA after pharmacological improvement of insulin sensitivity in IR patients (Asagami et al. 2002; Stuhlinger et al. 2002), conflicting results on the association between ADMA, NO production and HOMA‐IR have been reported subsequently (Pamuk et al. 2010; Siervo & Bluck, 2012; Tanrikulu‐Kucuk et al. 2015). These non‐conclusive results highlight the need to clarify the role of ADMA on endothelial dysfunction related to IR. In this sense, we provide evidence that the ADMA concentration is increased when IR arises not only at a systemic level (in the serum) in humans and rats, but also locally, both in homogenized adipose tissue surrounding human microarteries from IR‐MO subjects and in aortic tissue extracts from IRRs. Indeed, linear regression analysis showed a negative correlation between ADMA concentration and human endothelial function, measured as pD2 values, and a positive association with the IR parameter, HOMA‐IR. These results indicate that increased endogenous ADMA is clearly associated with endothelial dysfunction in the presence of IR. In some way related to this concept, intensive insulin therapy was shown to reduce the plasma concentrations of ADMA in critically ill patients (Siroen et al. 2005), and such an effect might explain the ability of insulin therapy to preserve endothelial function in these patients (Langouche et al. 2005).

Because DDAH activity is the key modulator of endogenous ADMA content, the expression of DDAH was determined. mRNA expression of both DDAH isoforms (1 and 2) in microarteries derived from obese subjects with IR was decreased compared to those with preserved insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, the expression of the dominant isoform of DDAH in metabolizing vascular ADMA, DDAH1 (Sydow et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2009), was significantly diminished in aortic extracts from rats displaying IR. These results are in agreement with previous studies showing decreased aortic DDAH1 content and DDAH activity in aortic tissues from rats with high‐fat‐induced IR (Chen et al. 2012). Considered globally, these findings suggest that the possible accumulation of endogenous ADMA might be a result of a reduction in the expression/activity of DDAH enzyme in IR. Indeed, preservation of DDAH has been proposed to contribute to the modulation of ADMA levels by insulin in addition to reduced protein breakdown and increased uptake of ADMA via transport systems (Siroen et al. 2006).

We further reasoned that, besides the involvement of ADMA in the modulation of the l‐arginine/NO pathway, the increased expression and/or activity of arginase plays a key role in compromising l‐arginine availability to eNOS and therefore would impact vascular function. The validity of this assumption was confirmed in the present study. First, a significant rise in arginase activity was observed in aortic tissue derived from IR rats compared to CRs. Additionally, we describe for the first time increased arginase‐2 gene expression in the microarteries of IR‐MO subjects with no parallel alteration in eNOS vascular expression, indicating that IR can differentially affect the expression of l‐arginine metabolizing enzymes. Previous studies have demonstrated the presence of an augmented expression and activity of arginase‐2 in the aorta of obese mice (Yu et al. 2014). In addition, increased activity of arginase has been detected in the serum and in the buffer of isolated aorta from rats fed with high levels of fructose for 12 weeks (El‐Bassossy et al. 2013). Furthermore, elevated plasma arginase activity was found in type 2 diabetic patients (Kashyap et al. 2008). Arginase up‐regulation in both IR humans and rats was accompanied by no significant changes in plasmatic arginine concentrations. Indeed, even a non‐significant reduction of arginine concentration was found in aortic tissue from IR rats, indicating a probable role for diminished l‐arginine bioavailability. This finding is of clinical importance because a clear association was found between reduced l‐arginine availability and increases in cardiovascular disease and mortality (Tang et al. 2009).

Potentially, elevated arginase activity would negatively impact vascular function under IR conditions. In this sense, genetic ablation of arginase‐2 fully preserved endothelial function (Yu et al. 2014) and prevented endothelial senescence (Yepuri et al. 2012). Consistent with this idea, we provide functional evidence suggesting that increased arginase activity and diminished l‐arginine availability impacts negatively endothelial function. Acute arginase inhibition with nor‐NOHA ameliorated endothelial malfunction associated with the IR state in human obesity and in fructose‐fed rats. Our findings confirm and expand previous studies showing that chronic arginase inhibition alleviates impaired endothelial‐dependent relaxation associated with IR in the rat aorta (El‐Bassossy et al. 2013) and recovers NO production in the aorta from obese mice (Chung et al. 2014). In addition, supplementation with l‐arginine improved endothelial function in large and small arteries from IRR, as well as in microarteries from obese subjects with IR. Such evidence suggests that the putative reduction in l‐arginine availability when generating endothelial NO results from both the increased concentration of a competitive antagonist (ADMA) and the hyperactivation of arginase under IR conditions.

A limitation of the present study is that ADMA content and arginase activity could not be determined in human vascular tissue because of the limited amount of microarteries dissected from each omentum specimen and the insufficient amount of protein obtained from these vascular samples that precluded any adequate guarantee of the methods of determination. We tried to overcome this limitation by making these determinations in vascular tissue from IRRs and by determining ADMA in adipose tissue surrounding mesenteric vessels and analysing arginase and DDAH‐1/2 expression at mRNA levels in mesenteric microvessels.

In conclusion, the present study identifies increased ADMA and up‐regulated arginase as determinant factors in the alteration of the l‐arginine/NO pathway, as well as the subsequent endothelial dysfunction associated with IR in human obesity and a well characterized non‐obese animal model of IR. We found that systemic and/or vascular levels of ADMA and arginase are increased by IR and that this enhancement is accompanied by impaired endothelial function (Fig. 7). Importantly, acute treatment of arteries derived from IR obese subjects or non‐obese IR animals with arginase inhibitor or with l‐arginine significantly improves endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation, most probably by increasing l‐arginine availability. These results provide novel insights regarding the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction related to obesity and IR and establish potential therapeutic targets for intervention.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of mechanisms involved in l‐arginine/NO pathway impairment caused by IR leading to endothelial dysfunction .

Development of the IR condition, either associated with obesity or not, results in the diminished expression of DDAH, the enzyme responsible for ADMA degradation, causing a significant intracellular elevation of ADMA and therefore interfering with the l‐arginine/NO signalling pathway. In addition, arginase is up‐regulated leading to an altered l‐arginine/NO pathway. These alterations result in defective NO‐mediate responses and subsequent endothelial dysfunction, which represents a first step toward cardiovascular disease.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

MEA, JA and LRM designed, analysed, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. MSR and ASF performed experiments, and analysed data. JCRD, MLP and AHM provided specimens and interpreted data. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

The present work was funded by grants received from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and cofunded by Fondos FEDER (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, PI11/01068, RETICEF RD12/0043), Spanish Government.

References

- Anderssohn M, Schwedhelm E, Luneburg N, Vasan RS & Boger RH (2010). Asymmetric dimethylarginine as a mediator of vascular dysfunction and a marker of cardiovascular disease and mortality: an intriguing interaction with diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res 7, 105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo J, Sanchez‐Ferrer CF, Peiro C, Marin J & Rodriguez‐Manas L (1996). Impairment of endothelium‐dependent relaxation by increasing percentages of glycosylated human hemoglobin. Possible mechanisms involved. Hypertension 28, 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asagami T, Abbasi F, Stuelinger M, Lamendola C, McLaughlin T, Cooke JP, Reaven GM & Tsao PS (2002). Metformin treatment lowers asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 51, 843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascaso JF, Romero P, Real JT, Priego A, Valdecabres C & Carmena R (2001). [Insulin resistance quantification by fasting insulin plasma values and HOMA index in a non‐diabetic population]. Med Clin (Barc) 117, 530–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger RH (2004). Asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, explains the ‘L‐arginine paradox’ and acts as a novel cardiovascular risk factor. J Nutr 134, 2842S‐2847S; discussion 2853S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke GL, Bertoni AG, Shea S, Tracy R, Watson KE, Blumenthal RS, Chung H & Carnethon MR (2008). The impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical vascular disease: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 168, 928–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplin B & Leiper J (2012). Endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitors in the biology of disease: markers, mediators, and regulators? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32, 1343–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Xia K, Zhao Z, Deng X & Yang T (2012). Atorvastatin modulates the DDAH1/ADMA system in high‐fat diet‐induced insulin‐resistant rats with endothelial dysfunction. Vasc Med 17, 416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JH, Moon J, Lee YS, Chung HK, Lee SM & Shin MJ (2014). Arginase inhibition restores endothelial function in diet‐induced obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 451, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das UN, Repossi G, Dain A & Eynard AR (2011). L‐arginine, NO and asymmetrical dimethylarginine in hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 16, 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante W, Johnson FK & Johnson RA (2007). Arginase: a critical regulator of nitric oxide synthesis and vascular function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34, 906–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Bassossy HM, El‐Fawal R, Fahmy A & Watson ML (2013). Arginase inhibition alleviates hypertension in the metabolic syndrome. Br J Pharmacol 169, 693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Assar M, Angulo J & Rodríguez‐Mañas L (2015. a). Diabetes and ageing induced vascular inflammation. J Physiol doi: 10.1113/JP270841. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Assar M, Angulo J, Santos‐Ruiz M, Moreno P, Novials A, Villanueva‐Penacarrillo ML & Rodriguez‐Mañas L (2015. b). Differential effect of amylin on endothelial‐dependent vasodilation in mesenteric arteries from control and insulin resistant rats. PLoS ONE 10, e0120479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Assar M, Ruiz de Adana JC, Angulo J, Pindado Martinez ML, Hernandez Matias A & Rodriguez‐Mañas L (2013). Preserved endothelial function in human obesity in the absence of insulin resistance. J Transl Med 11, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Assar M, Sanchez‐Puelles JM, Royo I, Lopez‐Hernandez E, Sanchez‐Ferrer A, Acena JL, Rodriguez‐Mañas L & Angulo J (2015. c). FM19G11 reverses endothelial dysfunction in rat and human arteries through stimulation of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway, independently of mTOR/HIF‐1alpha activation. Br J Pharmacol 172, 1277–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Tsuchihashi K, Sasao H, Eguchi M, Miurakami H, Hase M, Higashiura K, Yuda S, Hashimoto A, Miura T, Ura N & Shimamoto K (2008). Insulin resistance functionally limits endothelium‐dependent coronary vasodilation in nondiabetic patients. Heart Vessels 23, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Xu X, Zhu G, Atzler D, Kimoto M, Chen J, Schwedhelm E, Luneburg N, Boger RH, Zhang P & Chen Y (2009). Vascular endothelial‐specific dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase‐1‐deficient mice reveal that vascular endothelium plays an important role in removing asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation 120, 2222–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap SR, Lara A, Zhang R, Park YM & DeFronzo RA (2008). Insulin reduces plasma arginase activity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 31, 134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katakam PV, Ujhelyi MR & Miller AW (1999). EDHF‐mediated relaxation is impaired in fructose‐fed rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 34, 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocak H, Oner‐Iyidogan Y, Gurdol F, Oner P & Esin D (2011). Serum asymmetric dimethylarginine and nitric oxide levels in obese postmenopausal women. J Clin Lab Anal 25, 174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langouche L, Vanhorebeek I, Vlasselaers D, Vander Perre S, Wouters PJ, Skogstrand K, Hansen TK, Van den Berghe G (2005). Intensive insulin therapy protects the endothelium of critically ill patients. J Clin Invest 115, 2277–2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper JM, Santa Maria J, Chubb A, MacAllister RJ, Charles IG, Whitley GS & Vallance P (1999). Identification of two human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases with distinct tissue distributions and homology with microbial arginine deiminases. Biochem J 343, 209–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupattelli G, De Vuono S, Boni M, Helou R, Raffaele Mannarino M, Rita Roscini A, Alaeddin A, Pirro M & Vaudo G (2013). Insulin resistance and not BMI is the major determinant of early vascular impairment in patients with morbid obesity. J Atheroscler Thromb 20, 924–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marliss EB, Chevalier S, Gougeon R, Morais JA, Lamarche M, Adegoke OA & Wu G (2006). Elevations of plasma methylarginines in obesity and ageing are related to insulin sensitivity and rates of protein turnover. Diabetologia 49, 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF & Turner RC (1985). Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta‐cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin T, Stuhlinger M, Lamendola C, Abbasi F, Bialek J, Reaven GM & Tsao PS (2006). Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations are elevated in obese insulin‐resistant women and fall with weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91, 1896–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming XF, Rajapakse AG, Yepuri G, Xiong Y, Carvas JM, Ruffieux J, Scerri I, Wu Z, Popp K, Li J, Sartori C, Scherrer U, Kwak BR, Montani JP & Yang Z (2012). Arginase II promotes macrophage inflammatory responses through mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, contributing to insulin resistance and atherogenesis. J Am Heart Assoc 1, e000992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto M, Kotani K, Ishibashi S & Taniguchi N (2012). The effect of antihypertensive drugs on endothelial function as assessed by flow‐mediated vasodilation in hypertensive patients. Int J Vasc Med 2012, 453264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka KK, Papathanassiou K, Bechlioulis A, Pappas K, Kazakos N, Kanioglou C, Kostoula A, Vezyraki P, Makriyiannis D, Tsatsoulis A & Michalis LK (2012). Effects of pioglitazone and metformin on vascular endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with sulfonylureas. Diab Vasc Dis Res 9, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk BO, Torun AN, Kulaksizoglu M, Ertugrul D, Ciftci O, Kulaksizoglu S, Yildirim E & Demirag NG (2010). Asymmetric dimethylarginine levels and carotid intima‐media thickness in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and their relationship to metabolic parameters. Fertil Steril 93, 1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Maio R, Perticone M, Galiano Leone G, Bruni R, Di Cello S, Pascale A, Talarico G, Greco L, Andreozzi F & Sesti G (2010). Endothelial dysfunction, ADMA and insulin resistance in essential hypertension. Int J Cardiol 142, 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Maio R, Perticone M, Maas R, Boger RH, Tripepi G, Sesti G & Zoccali C (2005). Asymmetric dimethylarginine, L‐arginine, and endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 46, 518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope AJ, Karuppiah K & Cardounel AJ (2009). Role of the PRMT‐DDAH‐ADMA axis in the regulation of endothelial nitric oxide production. Pharmacol Res 60, 461–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto D, Contreras C & Sanchez A (2014). Endothelial dysfunction, obesity and insulin resistance. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 12, 412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven G (2012). Insulin resistance and coronary heart disease in nondiabetic individuals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32, 1754–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven GM (2011). Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am 95, 875–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Mañas L, Angulo J, Vallejo S, Peiro C, Sanchez‐Ferrer A, Cercas E, Lopez‐Doriga P & Sanchez‐Ferrer CF (2003). Early and intermediate Amadori glycosylation adducts, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction in the streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats vasculature. Diabetologia 46, 556–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Mañas L, El‐Assar M, Vallejo S, Lopez‐Doriga P, Solis J, Petidier R, Montes M, Nevado J, Castro M, Gomez‐Guerrero C, Peiro C & Sanchez‐Ferrer CF (2009). Endothelial dysfunction in aged humans is related with oxidative stress and vascular inflammation. Aging Cell 8, 226–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudofsky G, Roeder E, Merle T, Hildebrand M, Nawroth PP & Wolfrum C (2011). Weight loss improves endothelial function independently of ADMA reduction in severe obesity. Horm Metab Res 43, 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciacqua A, Grillo N, Quero M, Sesti G & Perticone F (2012). Asymmetric dimethylarginine plasma levels and endothelial function in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Mol Sci 13, 13804–13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Kashiwagi A, Nishio Y, Okamura T, Yoshida Y, Masada M, Toda N & Kikkawa R (1999). Abnormal biopterin metabolism is a major cause of impaired endothelium‐dependent relaxation through nitric oxide/O2 – imbalance in insulin‐resistant rat aorta. Diabetes 48, 2437–2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siervo M & Bluck LJ (2012). In vivo nitric oxide synthesis, insulin sensitivity, and asymmetric dimethylarginine in obese subjects without and with metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 61, 680–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siroen MP, Teerlink T, Nijveldt RJ, Prins HA, Richir MC & van Leeuwen PA (2006). The clinical significance of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Annu Rev Nutr 26, 203–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siroen MP, van Leeuwen PA, Nijveldt RJ, Teerlink T, Wouters PJ & Van den Berghe G (2005). Modulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine in critically ill patients receiving intensive insulin treatment: a possible explanation of reduced morbidity and mortality? Crit Care Med 33, 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhlinger MC, Abbasi F, Chu JW, Lamendola C, McLaughlin TL, Cooke JP, Reaven GM & Tsao PS (2002). Relationship between insulin resistance and an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. JAMA 287, 1420–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Takamisawa I, Yoshimasa Y & Harano Y (2007). Association between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes and the effects of pioglitazone. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 76, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydow K, Mondon CE, Schrader J, Konishi H & Cooke JP (2008). Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase overexpression enhances insulin sensitivity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28, 692–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang WH, Wang Z, Cho L, Brennan DM & Hazen SL (2009). Diminished global arginine bioavailability and increased arginine catabolism as metabolic profile of increased cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 53, 2061–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanrikulu‐Kucuk S, Kocak H, Oner‐Iyidogan Y, Seyithanoglu M, Topparmak E & Kayan‐Tapan T (2015). Serum fetuin‐A and arginase‐1 in human obesity model: is there any interaction between inflammatory status and arginine metabolism? Scand J Clin Lab Invest 75, 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance P, Leone A, Calver A, Collier J & Moncada S (1992). Accumulation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in chronic renal failure. Lancet 339, 572–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TM, Levy JC & Matthews DR (2004). Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 27, 1487–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z & Ming XF (2013). Arginase: the emerging therapeutic target for vascular oxidative stress and inflammation. Front Immunol 4, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepuri G, Velagapudi S, Xiong Y, Rajapakse AG, Montani JP, Ming XF & Yang Z (2012). Positive crosstalk between arginase‐II and S6K1 in vascular endothelial inflammation and aging. Aging Cell 11, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EJ, Hill MA, Wiehler WB, Triggle CR & Reid JJ (2008). Reduced EDHF responses and connexin activity in mesenteric arteries from the insulin‐resistant obese Zucker rat. Diabetologia 51, 872–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Rajapakse AG, Montani JP, Yang Z & Ming XF (2014). p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase is involved in arginase‐II‐mediated eNOS‐uncoupling in obesity. Cardiovasc Diabetol 13, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]