Abstract

The gastrointestinal endocrine cells are essential for life. They regulate the gastrointestinal motility, secretion, visceral sensitivity, absorption, local immune defense, cell proliferation and appetite. These cells act as sensory cells with specialized microvilli that project into the lumen that sense the gut contents (mostly nutrients and/or bacteria byproducts), and respond to luminal stimuli by releasing hormones into the lamina propria. These released hormones exert their actions by entering the circulating blood and reaching distant targets (endocrine mode), nearby structures (paracrine mode) or via afferent and efferent synaptic transmission. The mature intestinal endocrine cells are capable of expressing several hormones. A change in diet not only affects the release of gastrointestinal hormones, but also alters the densities of the gut endocrine cells. The interaction between ingested foodstuffs and the gastrointestinal endocrine cells can be utilized for the clinical management of gastrointestinal and metabolic diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome, obesity and diabetes.

Keywords: diet, endocrine cells, gut, microbiota, paracrine

1. Introduction

An intake of nutrients is essential for maintaining life, as they provide energy to the body, and also trigger other important body functions. The interaction between ingested foodstuffs and the gastrointestinal endocrine cells is a new emerging concept (1,2). Understanding this interaction is not only important for understanding the normal physiology and the role of ingested nutrients in gastrointestinal disorders and diseases, but also for managing certain gastrointestinal disorders (3–6).

New data on the interaction between ingested nutrients and the gastrointestinal endocrine cells obtained from basic science and clinical research have accumulated in the last few years. The present review aimed to interpret the newly gained knowledge so as to understand the role of this interaction.

2. Gastrointestinal endocrine cells

General

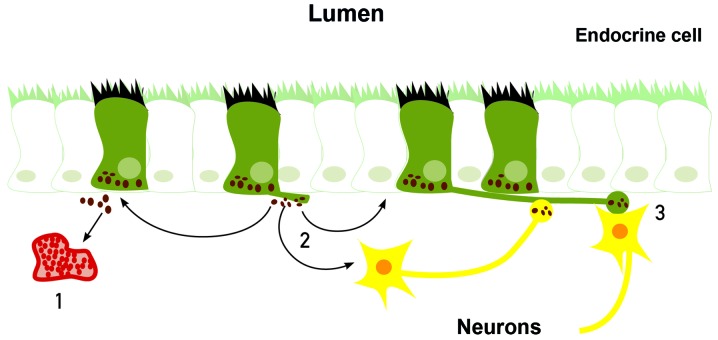

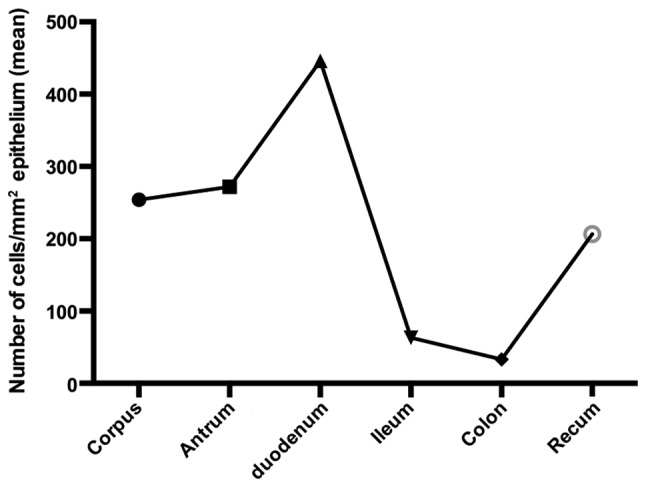

The gastrointestinal endocrine cells are scattered between the mucosal epithelial cells facing the intestinal lumen (Fig. 1) (7,8). There are ≥10 types of endocrine cell, and they are found in the stomach and the small and large intestines (8). Different segments of the gastrointestinal tract contain several different populations of gut endocrine cells (Fig. 2). Certain types of endocrine cells are located only in specific areas of the gastrointestinal tract. For example, serotonin- and somatostatin-secreting cells occur in the stomach and small and large intestines, while those producing ghrelin and gastrin are found only in the stomach, those producing secretin, cholecystokinin, gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) and motilin are found only in the upper small intestine, and those producing polypeptide YY (PYY), pancreatic polypeptide and oxyntomodulin are located only in the lower small intestine and large intestine (7,9–11). The densities of these cells vary in different sections of the gastrointestinal tract, with the density being highest in the duodenum (12–16) (Fig. 3). The gastrointestinal endocrine cells regulate gastrointestinal motility, secretion, absorption, visceral sensitivity, local immune defence, cell proliferation and appetite (7,17–31). These endocrine cells interact with each other and also with the enteric nervous system, and the afferent and efferent nerve fibers of the autonomic nervous system and the central nervous system (CNS) (7,18,22,32). Depletion of gastrointestinal endocrine cells as in congenital malabsorptive diarrhea caused by mutant neurogenin-3 (33), or complete loss of these cells in mutant mice with ablation of the transcript factor neurogenin-3 (34) show that the gastrointestinal endocrine cells are essential for life.

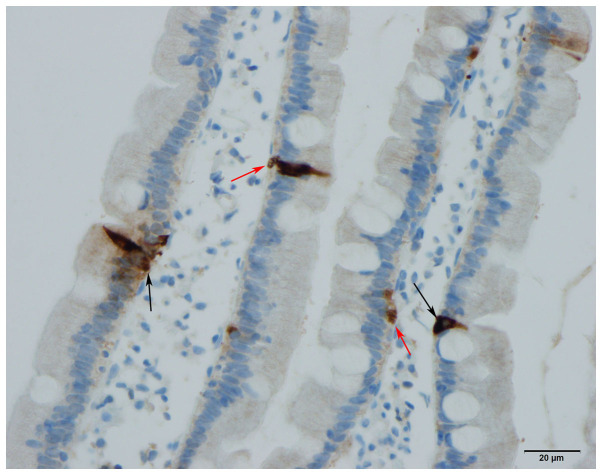

Figure 1.

Gastrointestinal endocrine cells are scattered between the epithelial cells lining the gastrointestinal lumen (black arrows). A basal cytoplasmic process can occasionally be observed (red arrow). Chromogranin A cells in human duodenum.

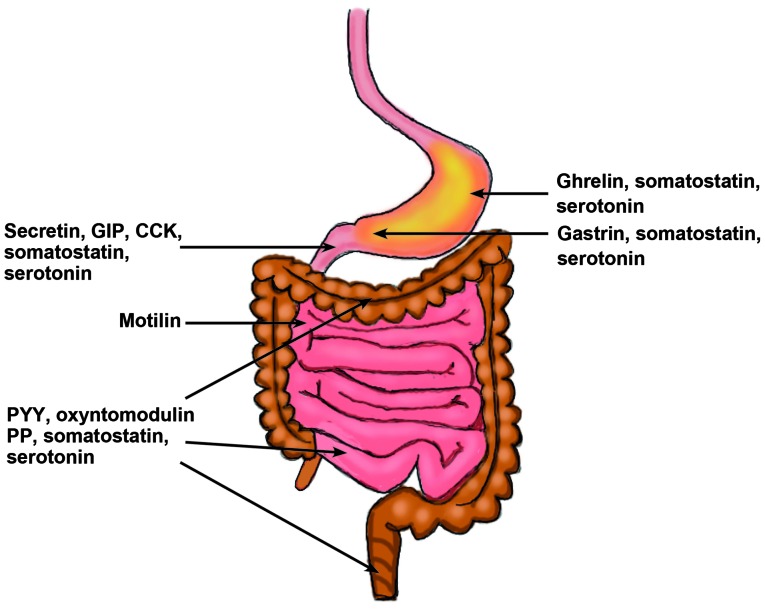

Figure 2.

Distribution of different gastrointestinal endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract.

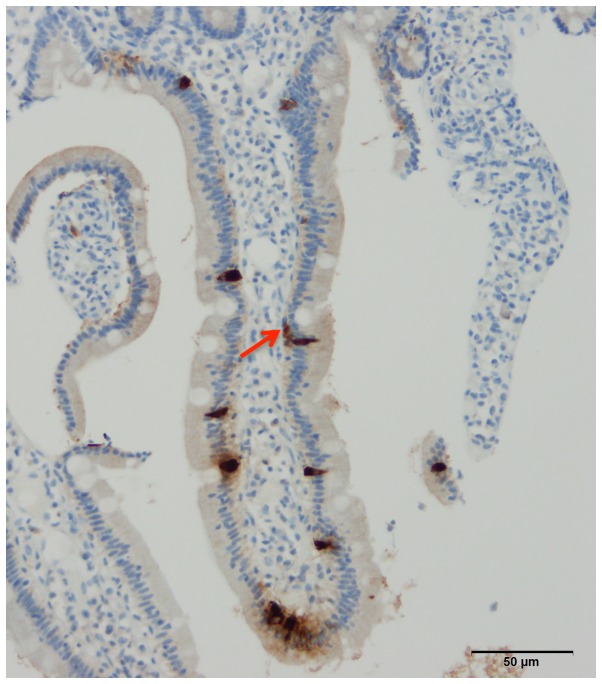

Figure 3.

Densities of endocrine cells in different segments of the gastrointestinal tract as detected by chromogranin A. These segments were immunostained using the same method and the same antibody, and were quantified in the same way in the same laboratory by a single person (12–16).

Immunohistochemical studies have shown that two hormones can be colocalized in the same endocrine cell type, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 and GIP in the small intestine as well as PYY and oxyntomodulin in the large intestine (34–38). Recent studies have further found that mature intestinal endocrine cells are capable of expressing several hormones (39,40).

Gastrointestinal endocrine cells as sensory cells

The gastrointestinal endocrine cells have specialized microvilli that project into the lumen and function as sensors of the gut contents (mostly nutrients and/or bacteria byproducts), and respond to luminal stimuli by releasing their hormones into the lamina propria (41–63). The gut intraluminal contents of carbohydrates, proteins and fats trigger the release of different signaling substances (such as hormones) from the gut endocrine cells (Table I) (41–53).

Table I.

Hormones released from the gastrointestinal endocrine cells depending on the gastrointestinal luminal contents of carbohydrates, proteins and fats.

| Gastrointestinal nutrients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Carbohydrates | Proteins | Fats |

| Hormones released | Gastric inhibitory polypeptide and oxyntomodulin | Pancreatic polypeptide, neuropeptide Y, motilin, ghrelin, and cholecystokinin (CCK) | Peptide YY, oxyntomodulin, motilin, ghrelin, and CCK |

Mode of action of gastrointestinal endocrine cells

The signaling substances (hormones) released from the gastrointestinal endocrine cells may exert their actions locally on nearby cells or neurons (paracrine mode) or by entering the circulating blood and reaching distant targets (endocrine mode) (64–67).

The gastrointestinal endocrine cells possess a basal cytoplasmic process, which is believed to facilitate the paracrine mode of action (Figs. 4 and 5) (68–72). This cytoplasmic process extends ≤70 µm, compared with the base of the endocrine cells being only 10 µm in diameter (70). This process has certain similarities to neuronal axons, and has been named a neuropod (70, 73–75). The neuropod has other axon-like characteristics, such as containing neurofilaments, being escorted by enteric glia cells, and expressing receptors for neurotrophins (74). Furthermore, gut endocrine cells have small clear synaptic vesicles, express several genes encoding for presynaptic proteins (synapsin 1, piccolo, bassoon, MUNC13B, regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2, latrophilin and transsynaptic neurexin), and also express postsynaptic genes (transsynaptic neuroligins 2 and 3, homer 3 and postsynaptic density 95) (75). Based on these data, it was concluded that the gut endocrine cells have the necessary elements for afferent and efferent synaptic transmission (75). Therefore, it appears that the gastrointestinal endocrine cells exert their effects via three modes of action: Endocrine, paracrine and synaptic (Fig. 6).

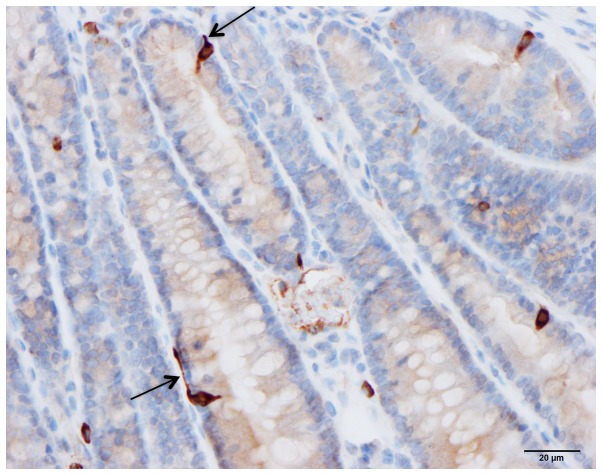

Figure 4.

Human duodenal secretin cells. Some of these cells possess a basal cytoplasmic process parallel to the basement membrane (arrow).

Figure 5.

Polypeptide YY cells in the colon of a rat. These cells possess a cytoplasmic process (arrow) similar to that observed in the human small intestine.

Figure 6.

Gastrointestinal endocrine cells may exert their effects via three modes of action: 1, By entering the circulating blood and reaching distant targets (endocrine mode); 2, by acting locally on nearby structures (paracrine mode); or 3, via synaptic activity.

The recent findings of gastrointestinal endocrine cells exhibiting endocrine and neuron-like characteristics support and revive the old hypothesis on the evolution of the neuroendocrine system of the gut (76). The observation that the mammalian gastrointestinal hormonal peptides occur in the CNS, but not in the gut of invertebrates (77–79), led to the hypothesis that the gastrointestinal endocrine cells of vertebrates originated in the nervous system of a common ancestor, and migrated during a later stage of evolution into the gut as scattered endocrine cells (76).

3. Interaction between diet and gastrointestinal cells

As aforementioned, the composition of the diet with different proportions of carbohydrates, proteins and fats is a trigger for the release of different gut hormones into the lamina propria. Furthermore, the ingested foodstuffs act as prebiotics for the intestinal microbiota, and the byproducts of the bacteria trigger also the release of hormones from the gut endocrine cells.

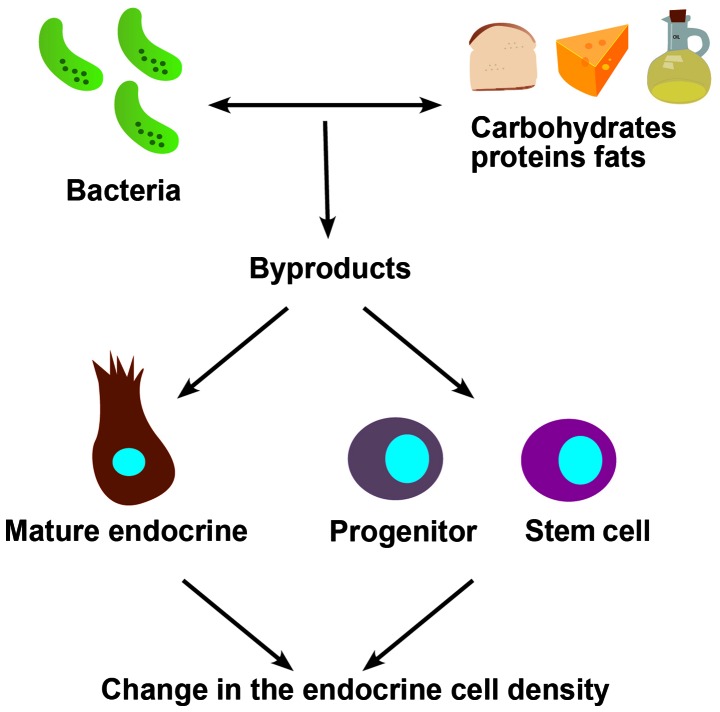

It has been shown recently that a change in diet is accompanied by a change in the density of gastrointestinal cells (3–6). This could be due to an ingested foodstuff acting as a prebiotic for the intestinal bacteria with the associated bacterial byproducts. These bacterial byproducts may act on the stem cells and/or differentiation progenitors, resulting in changes in the stem cell clonogenic activity and/or differentiation progeny. Alternatively, these bacterial byproducts could act on mature gastrointestinal cells to favor the expression of specific hormones (Fig. 7). Thus, the change in the density of a certain endocrine cell type could be caused by switching to the expression of a different hormone.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of the possible ways by which a change in diet could affect the density of gastrointestinal cells.

4. Conclusion

The diet is important for regulating the functions of gastrointestinal endocrine cells. It not only regulates the release of hormones from these cells, but also affects their densities. The interaction between nutrients and gastrointestinal endocrine cells could be useful for the clinical management of several diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome, obesity and diabetes (17,80–85).

References

- 1.El-Salhy M, Gilja OH, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Interaction between ingested nutrients and gut endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:363–371. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittermaier C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Oefferlbauer-Ernst A, Miehsler W, Beier M, Tillinger W, Gangl A, Moser G. Impact of depressive mood on relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective 18-month follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:79–84. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000106907.24881.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hausken T, El-Salhy M. Increased gastric chromogranin A cell density following changes to diets of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:2322–2326. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hausken T, El-Salhy M. Increased chromogranin A cell density in the large intestine of patients with irritable bowel syndrome after receiving dietary guidance. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:823897. doi: 10.1155/2015/823897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Effect of dietary management on the gastric endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;69:519–524. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Normalization of large intestinal endocrine cells following dietary management in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:175–178. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Salhy M, Seim I, Chopin L, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome: The role of gut neuroendocrine peptides. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:2783–2800. doi: 10.2741/E583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment options. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.May CL, Kaestner KH. Gut endocrine cell development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;323:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunawardene AR, Corfe BM, Staton CA. Classification and functions of enteroendocrine cells of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:219–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Salhy M, Grimelius L, Wilander E, Ryberg B, Terenius L, Lundberg JM, Tatemoto K. Immunocytochemical identification of polypeptide YY (PYY) cells in the human gastrointestinal tract. Histochemistry. 1983;77:15–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00496632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Salhy M, Gilja OH, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Duodenal chromogranin a cell density as a biomarker for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:462856. doi: 10.1155/2014/462856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Salhy M, Gilja OH, Hausken T. Chromogranin A cells in the stomachs of patients with sporadic irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:1753–1757. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Salhy M, Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hausken T. Chromogranin A cell density in the rectum of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:1223–1225. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Hausken T. Chromogranin A as a possible tool in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1435–1439. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.503965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Salhy M, Wendelbo IH, Gundersen D. Reduced chromogranin A cell density in the ileum of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:1241–1244. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Salhy M, Ostgaard H, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. The role of diet in the pathogenesis and management of irritable bowel syndrome (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:723–731. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151–5163. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mawe GM, Coates MD, Moses PL. Review article: Intestinal serotonin signalling in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1067–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wade PR, Chen J, Jaffe B, Kassem IS, Blakely RD, Gershon MD. Localization and function of a 5-HT transporter in crypt epithelia of the gastrointestinal tract. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2352–2364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02352.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershon MD, Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: From basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:397–414. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gershon MD. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:14–21. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835bc703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gershon MD. Serotonin is a sword and a shield of the bowel: Serotonin plays offense and defense. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012;123:268–280. discussion 280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Salhy M, Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. The role of peptide YY in gastrointestinal diseases and disorders (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:275–282. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubrasquet M, Bataille D, Gespach C. Oxyntomodulin (glucagon-37 or bioactive enteroglucagon): A potent inhibitor of pentagastrin-stimulated acid secretion in rats. Biosci Rep. 1982;2:391–395. doi: 10.1007/BF01119301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schjoldager BT, Baldissera FG, Mortensen PE, Holst JJ, Christiansen J. Oxyntomodulin: A potential hormone from the distal gut. Pharmacokinetics and effects on gastric acid and insulin secretion in man. Eur J Clin Invest. 1988;18:499–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1988.tb01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schjoldager B, Mortensen PE, Myhre J, Christiansen J, Holst JJ. Oxyntomodulin from distal gut. Role in regulation of gastric and pancreatic functions. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1411–1419. doi: 10.1007/BF01538078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dakin CL, Small CJ, Batterham RL, Neary NM, Cohen MA, Patterson M, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Peripheral oxyntomodulin reduces food intake and body weight gain in rats. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2687–2695. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wynne K, Park AJ, Small CJ, Patterson M, Ellis SM, Murphy KG, Wren AM, Frost GS, Meeran K, Ghatei MA, et al. Subcutaneous oxyntomodulin reduces body weight in overweight and obese subjects: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes. 2005;54:2390–2395. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1626–1635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1207068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jianu CS, Fossmark R, Syversen U, Hauso Ø, Waldum HL. A meal test improves the specificity of chromogranin A as a marker of neuroendocrine neoplasia. Tumour Biol. 2010;31:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seim I, El-Salhy M, Hausken T, Gundersen D, Chopin L. Ghrelin and the brain-gut axis as a pharmacological target for appetite control. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:768–775. doi: 10.2174/138161212799277806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Cortina G, Wu SV, Tran R, Cho JH, Tsai MJ, Bailey TJ, Jamrich M, Ament ME, Treem WR, et al. Mutant neurogenin-3 in congenital malabsorptive diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:270–280. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghia JE, Blennerhassett P, Deng Y, Verdu EF, Khan WI, Collins SM. Reactivation of inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model of depression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2280–2288. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.069. e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spångéus A, Forsgren S, el-Salhy M. Does diabetic state affect co-localization of peptide YY and enteroglucagon in colonic endocrine cells? Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:37–41. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pyarokhil AH, Ishihara M, Sasaki M, Kitamura N. The developmental plasticity of colocalization pattern of peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1 in the endocrine cells of bovine rectum. Biomed Res. 2012;33:35–38. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.33.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haroon E, Raison CL, Miller AH. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: Translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:137–162. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Salhy M, Wilander E, Grimelius L. Immunocytochemical localization of gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) in the human foetal pancreas. Ups J Med Sci. 1982;87:81–85. doi: 10.3109/03009738209178411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghia JE, Li N, Wang H, Collins M, Deng Y, El-Sharkawy RT, Côté F, Mallet J, Khan WI. Serotonin has a key role in pathogenesis of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1649–1660. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dryden S, Wang Q, Frankish HM, Pickavance L, Williams G. The serotonin (5-HT) antagonist methysergide increases neuropeptide Y (NPY) synthesis and secretion in the hypothalamus of the rat. Brain Res. 1995;699:12–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00841-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandström O, El-Salhy M. Ageing and endocrine cells of human duodenum. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;108:39–48. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(98)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Salhy M. Ghrelin in gastrointestinal diseases and disorders: A possible role in the pathophysiology and clinical implications (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:727–732. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tolhurst G, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Intestinal sensing of nutrients. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;209:309–335. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J, Cummings BP, Martin E, Sharp JW, Graham JL, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ, Raybould HE. Glucose sensing by gut endocrine cells and activation of the vagal afferent pathway is impaired in a rodent model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R657–R666. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00345.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker HE, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Molecular mechanisms underlying nutrient-stimulated incretin secretion. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e1. doi: 10.1017/S146239940900132X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raybould HE. Nutrient sensing in the gastrointestinal tract: Possible role for nutrient transporters. J Physiol Biochem. 2008;64:349–356. doi: 10.1007/BF03174091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.San Gabriel A, Nakamura E, Uneyama H, Torii K. Taste, visceral information and exocrine reflexes with glutamate through umami receptors. J Med Invest. 2009;56:209–217. doi: 10.2152/jmi.56.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudholm T, Wallin B, Theodorsson E, Näslund E, Hellström PM. Release of regulatory gut peptides somatostatin, neurotensin and vasoactive intestinal peptide by acid and hyperosmolal solutions in the intestine in conscious rats. Regul Pept. 2009;152:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sternini C, Anselmi L, Rozengurt E. Enteroendocrine cells: A site of ‘taste’ in gastrointestinal chemosensing. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008;15:73–78. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f43a73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sternini C. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. IV. Functional implications of bitter taste receptors in gastrointestinal chemosensing. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G457–G461. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00411.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchan AM. Nutrient Tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut III. Endocrine cell recognition of luminal nutrients. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1103–G1107. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montero-Hadjadje M, Elias S, Chevalier L, Benard M, Tanguy Y, Turquier V, Galas L, Yon L, Malagon MM, Driouich A, et al. Chromogranin A promotes peptide hormone sorting to mobile granules in constitutively and regulated secreting cells: Role of conserved N- and C-terminal peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12420–12431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shooshtarizadeh P, Zhang D, Chich JF, Gasnier C, Schneider F, Haïkel Y, Aunis D, Metz-Boutigue MH. The antimicrobial peptides derived from chromogranin/secretogranin family, new actors of innate immunity. Regul Pept. 2010;165:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reber SO, Obermeier F, Straub RH, Falk W, Neumann ID. Chronic intermittent psychosocial stress (social defeat/overcrowding) in mice increases the severity of an acute DSS-induced colitis and impairs regeneration. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4968–4976. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milde AM, Murison R. A study of the effects of restraint stress on colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in singly housed rats. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2002;37:140–150. doi: 10.1007/BF02688826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furness JB, Kunze WA, Clerc N. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut. II. The intestine as a sensory organ: Neural, endocrine, and immune responses. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G922–G928. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.5.G922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hassani H, Lucas G, Rozell B, Ernfors P. Attenuation of acute experimental colitis by preventing NPY Y1 receptor signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G550–G556. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00182.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cani PD, Everard A, Duparc T. Gut microbiota, enteroendocrine functions and metabolism. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cani PD, Hoste S, Guiot Y, Delzenne NM. Dietary non-digestible carbohydrates promote L-cell differentiation in the proximal colon of rats. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:32–37. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507691648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petitto JM, Huang Z, McCarthy DB. Molecular cloning of NPY-Y1 receptor cDNA from rat splenic lymphocytes: Evidence of low levels of mRNA expression and [125I]NPY binding sites. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;54:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De la Fuente M, Bernaez I, Del Rio M, Hernanz A. Stimulation of murine peritoneal macrophage functions by neuropeptide Y and peptide YY. Involvement of protein kinase C. Immunology. 1993;80:259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shibata M, Hisajima T, Nakano M, Goris RC, Funakoshi K. Morphological relationships between peptidergic nerve fibers and immunoglobulin A-producing lymphocytes in the mouse intestine. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Painsipp E, Herzog H, Sperk G, Holzer P. Sex-dependent control of murine emotional-affective behaviour in health and colitis by peptide YY and neuropeptide Y. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1302–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rindi G, Inzani F, Solcia E. Pathology of gastrointestinal disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:713–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:13–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bertrand PP. The cornucopia of intestinal chemosensory transduction. Front Neurosci. 2009;3:48. doi: 10.3389/neuro.21.003.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bertrand PP, Bertrand RL. Serotonin release and uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Salhy M, Grimelius L, Wilander E, Abu-Sinna G, Lundqvist G. Histological and immunohistochemical studies of the endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal mucosa of the toad (Bufo regularis) Histochemistry. 1981;71:53–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00592570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sandstrom O. Age-related changes in the neuroendocrine system of the gut. Umea Univ Med Diss. 1999;617:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bohórquez DV, Chandra R, Samsa LA, Vigna SR, Liddle RA. Characterization of basal pseudopod-like processes in ileal and colonic PYY cells. J Mol Histol. 2011;42:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s10735-010-9302-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gustafsson BI, Bakke I, Hauso Ø, Kidd M, Modlin IM, Fossmark R, Brenna E, Waldum HL. Parietal cell activation by arborization of ECL cell cytoplasmic projections is likely the mechanism for histamine induced secretion of hydrochloric acid. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:531–537. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.558113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gustafsson BI, Bakke I, Tømmerås K, Waldum HL. A new method for visualization of gut mucosal cells, describing the enterochromaffin cell in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:390–395. doi: 10.1080/00365520500331281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pang XH, Li TK, Xie Q, He FQ, Cui J, Chen YQ, Huang XL, Gan HT. Amelioration of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by neuropeptide Y antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1047–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0964-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bohórquez DV, Samsa LA, Roholt A, Medicetty S, Chandra R, Liddle RA. An enteroendocrine cell-enteric glia connection revealed by 3D electron microscopy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bohórquez DV, Shahid RA, Erdmann A, Kreger AM, Wang Y, Calakos N, Wang F, Liddle RA. Neuroepithelial circuit formed by innervation of sensory enteroendocrine cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:782–786. doi: 10.1172/JCI78361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.El-Salhy M. On the phylogeny of the gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) neuroendocrine system. Acta Uni Uppsal. 1981;385:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 77.El-Salhy M, Abou-el-Ela R, Falkmer S, Grimelius L, Wilander E. Immunohistochemical evidence of gastro-entero-pancreatic neurohormonal peptides of vertebrate type in the nervous system of the larva of a dipteran insect, the hoverfly, Eristalis aeneus. Regul Pept. 1980;1:187–204. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(80)90271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Salhy M, Falkmer S, Kramer KJ, Speirs RD. Immunohistochemical investigations of neuropeptides in the brain, corpora cardiaca, and corpora allata of an adult lepidopteran insect, Manduca sexta (L) Cell Tissue Res. 1983;232:295–317. doi: 10.1007/BF00213788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El-Salhy M, Falkmer S, Kramer KJ, Speirs RD. Immunocytochemical evidence for the occurrence of insulin in the frontal ganglion of a Lepidopteran insect, the tobacco hornworm moth, Manduca sexta L. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1984;54:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(84)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Effects of dietary guidance on the symptoms, quality of life and habitual dietary intake of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:845–852. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1382–1390. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.García-Martínez JM, Chocarro-Calvo A, De la Vieja A, García-Jiménez C. Insulin drives glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide expression via glucose-dependent regulation of FoxO1 and LEF1/β-catenin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:1141–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.García-Martínez JM, Chocarro-Calvo A, Moya CM, García-Jiménez C. WNT/beta-catenin increases the production of incretins by entero-endocrine cells. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1913–1924. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Freeland KR, Wilson C, Wolever TM. Adaptation of colonic fermentation and glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion with increased wheat fibre intake for 1 year in hyperinsulinaemic human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:82–90. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Korner J, Bessler M, Inabnet W, Taveras C, Holst JJ. Exaggerated glucagon-like peptide-1 and blunted glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide secretion are associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass but not adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]