Abstract

Although epidemiological studies propose aggressive and non-aggressive forms of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), they cannot be identified with conventional histopathology. We now report a retrospective study of human biopsy samples using biomarker ratio imaging microscopy (BRIM). Using BRIM, micrographs of biomarkers whose expression correlates with breast cancer aggressiveness are divided by micrographs of biomarkers whose expression negatively correlates with aggressiveness to create computed micrographs reflecting aggressiveness. The biomarker pairs CD44/CD24, N-cadherin/E-cadherin, and CD74/CD59 stratified DCIS samples. BRIM identified subpopulations of DCIS lesions with ratiometric properties resembling either benign fibroadenoma or invasive carcinoma samples. Our work confirms the existence of distinct subpopulations of DCIS lesions, which will likely have utility in breast cancer research and clinical practice.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast is the most common type of non-invasive breast cancer. In DCIS, epithelial cells proliferate within ducts, which are surrounded by a double layer of myoepithelial cells and basement membranes. Although it is believed that DCIS lesions become invasive breast cancer, this has not been proven, nor has the fraction of DCIS cases progressing to invasive cancer been established. The introduction of mammography led to a sharp increase in the number of DCIS cases. This increase, however, was not accompanied by a commensurate reduction in the number of advanced breast cancer patients. Several studies indicate that patients with insignificant disease are being treated1,2,3,4,5, which suggests the existence of both non-aggressive and aggressive forms of DCIS. Presently, it is not possible to stratify DCIS lesions according to aggressiveness with a precision sufficient to provide prognostic insight in patient care. To better classify DCIS lesions, we now introduce biomarker ratio imaging microscopy (BRIM). Ratio imaging microscopy has been used in calcium, membrane potential, intracellular pH, protein activation, fluorescence polarization, viscosity, proximity, and water permeability studies6,7,8,9,10. Two images are collected during ratio imaging microscopy: one increasing and one decreasing in intensity with the parameter of interest. Either one or two fluorescent labels may be used for ratioing6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. During BRIM fluorescence images of two biomarkers are collected at distinct wavelengths wherein the expression of one biomarker increases with tumor aggressiveness while the second decreases with aggressiveness. By dividing the former by the latter, high contrast images linked with tumor aggressiveness are created. Moreover, optical artifacts due to variations in sample thickness disappear. Our work identifies DCIS lesions exhibiting high or low levels of ratiometric biomarker expression linked with tumor aggressiveness.

Results

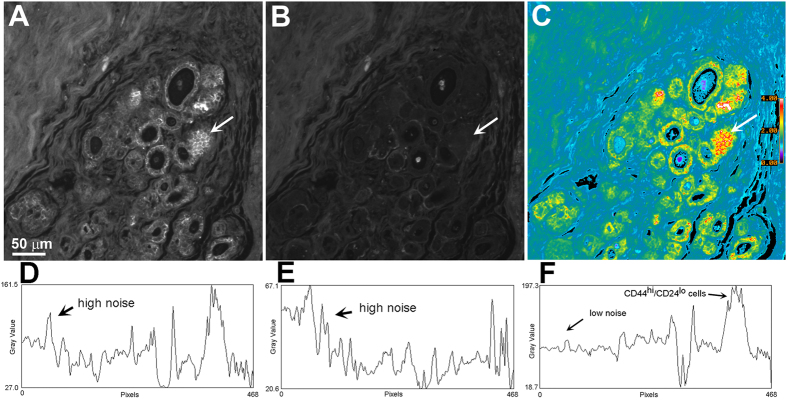

To illustrate BRIM, we localized CD44hi/CD24lo cells in DCIS pathology samples. CD44 and CD24 are cell surface adhesive proteins participating in proliferation and differentiation17. Importantly, CD44hi/CD24lo cells have been reported to represent a population of breast cancer stem cells18, which were herein visualized by ratioing CD44 (numerator image) against CD24 (denominator image). Figure 1A–C shows: CD44, CD24, and CD44hi/CD24lo images, respectively. The presence of high ratio cells in the ducts should be noted in Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1D. Quantitative line profile analyses of Fig. 1A–C are shown in panels D–F, respectively. These data illustrate the improvements provided by BRIM. For example, note that the parallel increases in CD44 and CD24 intensity seen in the region labeled “high noise” in Fig. 1D,E cancel out during ratioing, thus highlighting CD44hi/CD24lo cells. However, CD44hi/CD24lo cells could not be observed in a sub-population DCIS samples (see below).

Figure 1. Illustration of BRIM.

A DCIS section was labeled with anti-CD44 (A) and anti-CD24 (B). (Panels A,B) were prepared identically. (Panel C) reveals intraductal CD44hi/CD24lo cells at high contrast. The white arrows identify a region of CD44hi/CD24lo cells that are included in the quantitative line profile analyses of (panels D–F). (Panels D–F) show quantitative line profile analyses (the line profile extends from the right to left hand sides of the image at the level of the arrow). Noise reduction and contrast enhancement are seen in the ratio image of (panel F). The pseudocolor image in (panel C) is scaled as indicated by the bar on the right side. (Distance scale range is shown on the lower left side of (panel A).

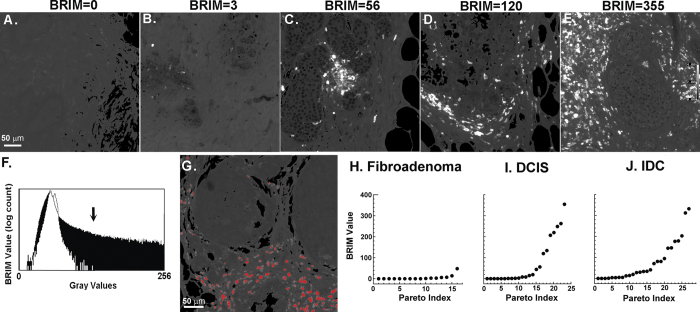

On the basis of prior biomarker research19,20,21, we studied CD74hi/CD59lo cells in DCIS samples. Overexpression of CD74, the HLA class II γ chain, and underexpression of CD59, a complement regulatory protein, are linked to poor patient outcomes20,21. Figure 2A–E shows the widely varying ratiometric intensities of five DCIS samples labeled for CD74 and CD59 biomarkers. Micrographs were next quantified for statistical purposes. We first compared pixel intensity histograms of control breast tissue (white region; low BRIM value) with DCIS tissue expressing aggressive biomarker properties (black region; high BRIM value); gray values >130 were only found in the DCIS sample (Fig. 2F). Figure 2G shows an image wherein gray values >130 were labeled red, which shows that stromal cells, not intraductal cells (Fig. 1C) were labeled. This threshold, based upon differences in clinical breast tissue samples, was applied in subsequent analyses. The results of this segmentation procedure were nearly indistinguishable from that obtained using a non-interactive Otsu algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 2). Figure 2I shows the number of high BRIM value particles per 20x micrograph for each DCIS patient. The inflection point found in the Pareto plot of panel I suggests two sample populations with mean particle counts of 4 ± 6 and 190 ± 100, which is further supported by Ashmann’s bimodality test22. These two populations were distinguishable at a high level of statistical significance (P < 0.0001). Quantitative data from simple fibroadenoma (5 ± 12) and IDC (76 ± 94) samples are shown as biological reference standards of benign and invasive breast neoplasms (Fig. 2H,J). Our studies demonstrate that BRIM stratifies DCIS samples. The IDC plot (Fig. 2J) was similar to DCIS samples (Fig. 2I). BRIM micrographs illustrating IDC staining are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The low BRIM DCIS subtype resembles the ratiometric biomarker properties of fibroadenoma samples whereas the high BRIM DCIS subtype more closely resembles IDC samples.

Figure 2. Stratification of DCIS samples using tissue sections stained with anti-CD74 and anti-CD59.

A broad range of stromal cell ratio values were observed for samples from five DCIS patients (panels A–E). To quantify these data, further image processing was performed. The ratio of each pixel in a sample of normal tissue is shown in the white plot of (panel F) whereas an identical plot of DCIS tissue is shown as black in this panel. This diagram shows that gray values of >130 (see arrow) are only found in the DCIS sample. (Panel G) shows pixels with gray values of >130 (color-coded red), which confirms that stromal cells account for high BRIM values. The ascending Pareto plots of (panels H–J) show electronic counts of CD74hi/CD59lo particles (ordinate) versus the data point index (abscissa). Each dot represents the BRIM score of one patient. Samples from simple fibroadenoma patients (H) display little or no signals (N = 16). DCIS samples (I) segregate into two populations: those scoring near the level of fibroadenomas and those samples scoring highly for the biomarker ratio pair (N = 23). High levels of statistical significance (P < 0.0001) are seen in comparing the low BRIM with high BRIM samples. The high BRIM scores can be seen for the DCIS population and IDC patient samples (J) (N = 26). Quantitative BRIM counts are shown at the top of (panels A–E). A ratio scale is given on the far right of (panel E) (20× objective).

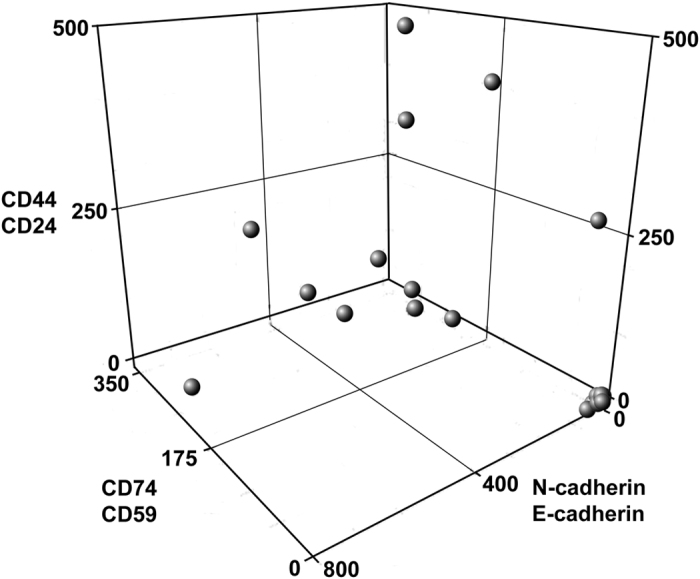

As DCIS lesions may become aggressive independently of stromal cell phenotype, we examined additional biomarkers. As the endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is believed to participate in metastasis23, we quantified N-cadherinhi/E-cadherinlo labeling. Similarly, CD44hi/CD24lo cells also contribute to aggressiveness18. CD44hi/CD24lo and N-cadhi/E-cadlo cells were found to stratify DCIS tissues lesions (Supplementary Fig. 4)(for examples of relevant micrographs, see Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). Figure 3 shows a three dimensional plot of CD74hi/CD59lo, CD44hi/CD24lo and N-cadhi/E-cadlo BRIM findings for each patient. This plot reveals a low BRIM DCIS sub-population near the origin (0, 0, 0) and a second subtype far from the origin. Although no significant correlation between BRIM subtype and nuclear grade or estrogen receptor status was observed, the average age of patients whose samples had low BRIM scores (50 yrs) was significantly (P < 0.05) less than those with high BRIM scores (64 yrs) (Supplementary Table 1), which is consistent with recent studies24. Within this dataset 5 samples (22%) had scores of 0–2 for CD74hi/CD59lo and CD44/CD24 as well as <50 for N-cadhi/E-cadlo (this higher score corrects for N-cadhi/E-cadlo stromal cells), suggesting a low level of aggressive biomarker labeling.

Figure 3. A three-dimensional rendering of all BRIM data for DCIS patients.

Values of the parameters CD74/CD59 (z axis), CD44/CD24 (x axis) and N-cadherin/E-cadherin (y axis) are plotted for each DCIS patient. Some samples18 had BRIM values far from the origin (0, 0, 0). Of the samples near the origin, 5 had scores of <50 for CD74/CD59 and 0–2 for the other two parameters. Note that DCIS samples near the walls of the three-dimensional plot could be interpreted as false-negatives if only one BRIM parameter was measured.

To illustrate the advantages of BRIM over conventional fluorescence imaging, we compared BRIM results with matched conventional fluorescence micrographs of numerator images. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows quantitative DCIS results comparing particle counts of N-cadherin images with particle counts of matched N-cadhi/E-cadlo images. Although some level of correlation is expected because N-cad images are incorporated in N-cadhi/E-cadlo images, statistical analysis indicates that these two measures only weakly correlate (R = 0.61). BRIM findings of N-cadhi/E-cadlo cells substantially differ from those of conventional fluorescence microscopy (N-cadhi cells). Similarly, weak correlations were observed for comparisons of CD44 versus CD44hi/CD24lo (R = 0.76) and CD74 versus CD74hi/CD59lo (R = 0.76). We speculate that analysis of a single biomarker may be insufficient to provide reliable prognostic information, and that multi-dimensional BRIM may be useful in breast cancer research and patient management.

Discussion

Although screening tools for cervical and colorectal cancer reduced the incidence of advanced forms of these diseases, screening mammography has not yielded a similar reduction in advanced breast cancer1,2,3. Esserman and colleagues2,5 have proposed that DCIS subtypes differing in aggressiveness exist. Our BRIM studies using biomarkers of breast cancer aggressiveness have identified DCIS subtypes thereby confirming the postulate of Esserman and others regarding the heterogeneity of DCIS subtypes. Our study also provides the first robust images of CD44hi/CD24lo cells within human tissue samples. The detection of these cells should accelerate the search for new anti-stem cell cancer drugs. As CD44hi/CD24lo cells may contribute to the failure of chemotherapy and radiotherapy18,25, their abundance and/or ratiometric values may provide predictive information. The identification of intraductal N-cadhi/E-cadlo cells indicates that the EMT accompanies human cancer, not just murine cancer26. In some DCIS cases a sub-population of CD74hi/CD59lo stromal cells can be observed. We speculate that stromal cells may participate in disease, as others have suggested27,28.

As a microscope-based tool, BRIM recognizes tumor cell heterogeneity, and permits biomarker detection at comparatively high concentrations within organelles. For image ratioing, the signal intensity must be linear with respect to biomarker number. Hence, enzyme-linked amplification methods are inappropriate due to their non-linear properties29. This difficulty is avoided by fluorescence microscopy. Variations in cell shape, size, and section thickness influence a sample’s perceived brightness. These optical path-length artifacts are removed by ratio imaging microscopy6,7. As instrument-dependent factors are present in the numerator and denominator, they are also removed by image ratioing, thereby improving standardization. Finally, noise due to sample loss during processing, knife chatter during sectioning and others are removed by ratioing (e.g., the upper left corner of Fig. 1A). Hence, BRIM overcomes many drawbacks of conventional histopathology.

As our samples originated from mastectomies without patient follow-up, we cannot know with certainty the lesions that would have progressed to life-threatening cancer. However, the association between the low BRIM scores of DCIS and fibroadenoma compared to the high BRIM scores of DCIS and IDC support the clinical relevance of these DCIS subtypes. The ability to stratify DCIS lesions and to identify potentially non-aggressive and aggressive lesions raises important issues in addressing overtreatment in breast cancer. BRIM is particularly attractive because it could be integrated into clinical pathology practices. Moreover, this approach may be useful in the cytologic study of aspirates in breast cancer and in peritoneal fluids in ovarian cancer. As overdiagnosis has also been reported for prostate, lung and other cancers30, BRIM may be broadly useful in cancer research and provide practitioners with important prognostic information in patient management.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Samples

In this study we used BRIM to evaluate the co-expression of biomarkers correlating and anti-correlating with breast cancer aggressiveness in a retrospective study of DCIS samples. We used fibroadenoma of the breast and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) to compare with DCIS samples. Formal-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) pathology samples were purchased from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI), a National Resource Center (Bethesda, MD) and the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CFTN) (Columbus, OH; Philadelphia, PA; and Nashville, TN). Samples were from mastectomies of females aged 37–96 years after informed consent was obtained from all subjects. As the tissues examined in this study were not needed for patient care, it is possible that small DCIS lesions were not adequately sampled. Samples from NDRI were collected between Nov. 2004 and Dec. 2014. The use of human material was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on the use of material in scientific research. These studies were approved by the University of Michigan’s IRB.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers were selected based upon their relative changes in expression in normal tissue vs. IDC. Although a high dynamic range of intensities is desirable, intensity differences causing division by zero errors are unhelpful. Punctate biomarker images (e.g., ribosomal biomarkers) and biomarkers that translocate between organelles (e.g., gene regulatory proteins) are also unsuitable for ratioing. The biomarkers used in this study have been previously reported, as described above. Our studies focus on the biomarker pairs: CD74hi/CD59lo, CD44hi/CD24lo and N-cadhi/E-cadlo, which are plasma membrane proteins.

As antibodies may differ in their titer, epitope recognition, and binding after antigen retrieval, it is important to use matched antibodies in BRIM. The primary antibodies used in these studies were: Ms anti-N-Cadherin (Abcam ab98952), Rb anti-E-Cadherin (Abcam ab15148), Ms anti-CD74 (Abcam ab9514), Rb anti-CD59 (Abcam ab133707), Rb anti-CD44 (Abcam ab41478), Ms anti-CD24 (Biolegend 311102). The secondary antibodies used in this study were: Gt anti-Ms Alexa 488 (Invitrogen A11029) and Dk anti-Rb Alexa 568 (Invitrogen A10042). These antibodies were typically used at a 1/100 dilution.

Histochemistry of tissue sections

Sections of paraffin-embedded samples were cut into 5 μm sections. Sections were stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E). For immunofluorescence staining, sections were deparaffinized and re-hydrated by sequential incubation in a graded ethanol series. After rehydration in PBS, sections were subjected to heat-mediated antigen retrieval in 10 mM citric acid buffer, pH 6.0. Sections were blocked using 10% non-fat dried milk for 1.5 hr. at room temperature. After blocking procedures, sections were incubated with 2 μg/mL of antibody diluted in 1% BSA in PBS overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, the sections were washed with PBS. Finally, the sections were incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody for 1.5 hr., washed with PBS, and then mounted in 90% glycerol in PBS. The H&E and immunofluorescence images were acquired from serial sections from each block.

Optical microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and an Andor iXon camera (Andor Technology, Belfast, Northern Ireland) with a 100 W mercury lamp. Ratio imaging experiments were performed as we have described13,14. To avoid cross-talk between the emission wavelengths of the fluorescent tags, band-pass filters with the “sharpest” cut-offs and greatest out-of-band reflectances were used (Chroma ET-fluorescein filter set (#49011) and Chroma ET-Cy3/rhodamine filter set (#49004) (Chroma Tech. Corp., Bella Falls, VT)). These zero pixel shift optics were chosen for their high performance in ratio imaging. For most experiments, 20 images, each acquired for 0.2 sec., were averaged. The electron multiplying charge coupled device chip was cooled to −85 °C. Typical camera settings were: multiplication gain, 150; vertical shift speed, 3.04 msec./pixel and 14-bit digitization at 10 MHz. Images were captured with Metamorph and processed with MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA) to calculate image ratios. Micrographs were evaluated using ImageJ software. Segmentation was performed with the ISODATA (iterative self-organizing data analysis) technique. A local implementation of the Otsu algorithm31 was used for comparison. (Global segmentation is recommended over local implementations of thresholding approaches, as fat droplets in mammary tissue may be misinterpreted by software.) Ratiometric images at a gray value of >130 were quantified by counting the number particles five or more pixels in size. The highest BRIM value from each patient’s micrographs was plotted. Several micrographs from each patient sample were analyzed because some micrographs contained lower numbers of cells, for example, due to an abundance of fatty tissue. Data were displayed using two-dimensional (KaleidaGraph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA) or three-dimensional (Plotly, Montreal, Quebec, CA) graphing software.

Statistics

In vitro data are presented as the mean ± sd to describe the dispersion of the data. Data were evaluated with Student’s t-test. Welch’s t-test, which is less susceptible to departures from a normal distribution, yielded indistinguishable results.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Clark, A. J. and Petty, H. R. Identification of lesion subtypes in biopsies of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast using biomarker ratio imaging microscopy. Sci. Rep. 6, 27039; doi: 10.1038/srep27039 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Mildred E. Swanson Foundation and the NIH (EY007003). We thank Karen Rosenspire, M.D., Ph.D. and Paul Savage, M.D. for helpful comments. We thank Lynn Spitzer, Ph.D. for helpful comments regarding statistical evaluations.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.J.C. performed the imaging experiments. H.R.P. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Bleyer A. & Welch H. G. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1998–2005 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozanne E. M. et al. Characterizing the impact of 25 years of DCIS treatment. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 129, 165–73 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding C. et al. Breast cancer screening, incidence, and mortality across US counties. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 1483–1489 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E. Breast cancer. Dare to do less. Science 343, 1454–6 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman L. J., Thompson I. M. & Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: An opportunity for improvement. JAMA 310, 797–8 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright G. R., Fisher G. W., Rogowska J. & Taylor D. L. Fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 30, 157–92 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty H. R. Fluorescence microscopy: established and emerging methods, experimental strategies, and applications in immunology. Microsc. Res. Tech. 70, 687–709 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donà E. et al. Directional tissue migration through a self-generated chemokine gradient. Nature 503, 285–9 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D. Fluorescence polarization microscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 30, 333–352 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbant P., Hodgson L., Kraynov V., Toutchkine A. & Hahn K. M. Activation of endogenous Cdc42 visualized in living cells. Science 305, 1615–9 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P., Luscher C. & Niggli E. Photolysis of caged compounds characterized by ratiometric confocal microscopy: a new approach to homogeneously control and measure the calcium concentration in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium 19, 255–266 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floto R. A., Mahaut-Smith M. P., Somasundaram B. & Allen J. M. IgG-induced Ca2+ oscillations in differentiated U937 cells; a study using laser scanning confocal microscopy and co-loaded fluo-3 and fura-red fluorescent probes. Cell Calcium 18, 377–89 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. J., Diamond M., Elfline M. & Petty H. R. Calicum microdomains form within neutrophils at the neutrophil-tumor cell synapse: role in antibody-dependent target cell apoptosis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 59, 149–59 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. J. & Petty H. R. Observation of calcium microdomains at the uropod of living morphologically polarized human neutrophils using flash lamp-based fluorescence microscopy. Cytometry A 73, 673–8 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C. et al. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature 457, 901–5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez T. M., Robles E., Poo M. & Spitzer N. C. Filopodial calcium transients promote substrate-dependent growth cone turning. Science 291, 1983–7 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Gayol A. & Jothy S. Adhesion proteins in the biology of breast cancer: contribution of CD44. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 66, 149–56 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajj M., Wicha M. S., Benito-Hernandez A., Morrison S. J. & Clarke M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3983–8 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D. et al. Molecular markers in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Mol. Cancer Res. 1, 362–75 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metodieva G. et al. CD74-dependent deregulation of the tumor suppressor scribble in human epithelial and breast cancer cells. Neoplasia 15, 660–8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madjd Z. et al. Loss of CD59 expression in breast tumours correlates with poor survival. J. Pathol. 200, 633–9 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman K. M., Bird C. M. & Zepf S. E. Detecting bimodality in astronomical datasets. Astronomical J. 108, 2348–2361 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. & Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene 29, 4741–4751 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel S. et al. Digital Mammography screening: Does age influence the detection rates of low-, intermediate-, and high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ? Radiology. 278, 707–713, doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150322 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 672–9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford H. Cancer theory faces doubts. Nature 472, 273–4 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick N. A., Neilson E. G. & Moses H. L. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature 432, 332–337 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orimo A. & Weinberg R. A. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer: A novel tumor-promoting cell type. Cell Cycle 5, 1597–1601 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exbrayat J.-M. ed. Histochemical and Cytochemical Methods of Visualization. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pa. 299 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan R., Doust J. & Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ 344, e3502, doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3502 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Sys. Man. Cyber. 9, 62–66 (1979). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.